Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tagalog language

View on Wikipedia

| Tagalog | |

|---|---|

| Wikang Tagalog | |

| Pronunciation | [tɐˈɡaːloɡ] ⓘ |

| Native to | Philippines |

| Region | Katagalugan; Metro Manila (as Filipino), parts of Central Luzon, most of Calabarzon, parts of Mimaropa, northwestern Bicol Region, and Ilocos Region (southeast Pangasinan) |

| Ethnicity | Tagalog |

| Speakers | L1: 33 million (2023)[1] L2: 54 million (2020)[1] Total: 87 million (2020–2023)[1] |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects | |

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Philippines (as Filipino)

ASEAN (as Filipino) |

Recognised minority language in | Philippines (as a regional language and an auxiliary official language in the predominantly Tagalog-speaking areas of the Philippines) |

| Regulated by | Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | tl |

| ISO 639-2 | tgl |

| ISO 639-3 | tgl |

| Glottolog | taga1280 Tagalogictaga1269 Tagalog-Filipinotaga1270 Tagalog |

| Linguasphere | 31-CKA |

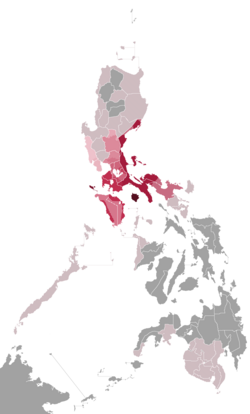

Predominantly Tagalog-speaking regions in the Philippines | |

Tagalog (/təˈɡɑːlɒɡ/ tə-GAH-log,[5] native pronunciation: [tɐˈɡaːloɡ] ⓘ; Baybayin: ) is an Austronesian language spoken as a first language by the ethnic Tagalog people, who make up a quarter of the population of the Philippines, and as a second language by the majority. Its de facto standardized and codified form, officially named Filipino, is the national language of the Philippines, and is one of the nation's two official languages, alongside English.

Tagalog is closely related to other Philippine languages, such as the Bikol languages, the Bisaya languages, Ilocano, Kapampangan, and Pangasinan, and more distantly to other Austronesian languages, such as the Formosan languages of Taiwan, Indonesian, Malay, Hawaiian, Māori, Malagasy, and many more.

Classification

[edit]Tagalog is a Central Philippine language within the Austronesian language family. Being Malayo-Polynesian, it is related to other Austronesian languages, such as Malagasy, Javanese, Indonesian, Malay, Tetum (of Timor), and Yami (of Taiwan).[6] It is closely related to the languages spoken in the Bicol Region and the Visayas islands, such as the Bikol group and the Visayan group, including Waray-Waray, Hiligaynon and Cebuano.[6]

Tagalog differs from its Central Philippine counterparts with its treatment of the Proto-Philippine schwa vowel *ə. In most Bikol and Visayan languages, this sound merged with /u/ and [o]. In Tagalog, it has merged with /i/. For example, Proto-Philippine *dəkət (adhere, stick) is Tagalog dikít and Visayan and Bikol dukót.

Proto-Philippine *r, *j, and *z merged with /d/ but is /l/ between vowels. Proto-Philippine *ŋajan (name) and *hajək (kiss) became Tagalog ngalan and halík. Adjacent to an affix, however, it becomes /r/ instead: bayád (paid) → bayaran (to pay).

Proto-Philippine *R merged with /ɡ/. *tubiR (water) and *zuRuʔ (blood) became Tagalog tubig and dugô.

History

[edit]

The word Tagalog is possibly derived from the endonym taga-ilog ("river dweller"), composed of tagá- ("native of" or "from") and ilog ("river"), or alternatively, taga-alog deriving from alog ("pool of water in the lowlands"; "rice or vegetable plantation"). Linguists such as David Zorc and Robert Blust speculate that the Tagalogs and other Central Philippine ethno-linguistic groups originated in Northeastern Mindanao or the Eastern Visayas.[7][8]

Possible words of Old Tagalog origin are attested in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription from the tenth century, which is largely written in Old Malay.[9] The first known complete book to be written in Tagalog is the Doctrina Christiana (Christian Doctrine), printed in 1593. The Doctrina was written in Spanish and two transcriptions of Tagalog; one in the ancient, then-current Baybayin script and the other in an early Spanish attempt at a Latin orthography for the language.

Throughout the 333 years of Spanish rule, various grammars and dictionaries were written by Spanish clergymen. In 1610, the Dominican priest Francisco Blancas de San José published the Arte y reglas de la lengua tagala (which was subsequently revised with two editions in 1752 and 1832) in Bataan. In 1613, the Franciscan priest Pedro de San Buenaventura published the first Tagalog dictionary, his Vocabulario de la lengua tagala in Pila, Laguna.

The first substantial dictionary of the Tagalog language was written by the Czech Jesuit missionary Pablo Clain in the beginning of the 18th century. Clain spoke Tagalog and used it actively in several of his books. He prepared the dictionary, which he later passed over to Francisco Jansens and José Hernandez.[10] Further compilation of his substantial work was prepared by P. Juan de Noceda and P. Pedro de Sanlucar and published as Vocabulario de la lengua tagala in Manila in 1754 and then repeatedly[11] reedited, with the last edition being in 2013 in Manila.[12]

Among others, Arte de la lengua tagala y manual tagalog para la administración de los Santos Sacramentos (1850) in addition to early studies[13] of the language.

The indigenous poet Francisco Balagtas (1788–1862) is known as the foremost Tagalog writer, his most notable work being the 19th-century epic Florante at Laura.[14]

Official status

[edit]

Tagalog was declared the official language by the first revolutionary constitution in the Philippines, the Constitution of Biak-na-Bato in 1897.[15] On the basis of the 1987 Constitution, Filipino, the national language of the Philippines, is designated as the official language. As the foundation of the national language, Tagalog symbolizes equality, unity, and national pride, reflecting the Filipino people’s shared commitment to social justice and inclusive nation-building.[16][17]

In 1935, the Philippine constitution designated English and Spanish as official languages, but mandated the development and adoption of a common national language based on one of the existing native languages.[18] After study and deliberation, the National Language Institute, a committee composed of seven members who represented various regions in the Philippines, chose Tagalog as the basis for the evolution and adoption of the national language of the Philippines.[19][20] President Manuel L. Quezon then, on December 30, 1937, proclaimed the selection of the Tagalog language to be used as the basis for the evolution and adoption of the national language of the Philippines.[19] In 1939, President Quezon renamed the proposed Tagalog-based national language as Wikang Pambansâ (national language).[20] Quezon himself was born and raised in Baler, Aurora, which is a native Tagalog-speaking area. Under the Japanese puppet government during World War II, Tagalog as a national language was strongly promoted; the 1943 Constitution specifying: "The government shall take steps toward the development and propagation of Tagalog as the national language."

In 1959, the language was further renamed as "Pilipino".[20] Along with English, the national language has had official status under the 1973 constitution (as "Pilipino")[21] and the present 1987 constitution (as Filipino).

Controversy

[edit]The adoption of Tagalog in 1937 as basis for a national language is not without its own controversies. Instead of specifying Tagalog, the national language was designated as Wikang Pambansâ ("National Language") in 1939.[19][22][better source needed] Twenty years later, in 1959, it was renamed by then Secretary of Education, José E. Romero, as Pilipino to give it a national rather than ethnic label and connotation. The changing of the name did not, however, result in acceptance among non-Tagalogs, especially Cebuanos who had not accepted the selection.[20]

The national language issue was revived once more during the 1971 Constitutional Convention. The majority of the delegates were in favor of scrapping the idea of a "national language" altogether.[23] A compromise solution was worked out—a "universalist" approach to the national language, to be called Filipino rather than Pilipino. The 1973 constitution makes no mention of Tagalog. When a new constitution was drawn up in 1987, it named Filipino as the national language.[20] The constitution specified that as the Filipino language evolves, it shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages. However, more than two decades after the institution of the "universalist" approach, there seems to be little if any difference between Tagalog and Filipino.[citation needed]

Use in education

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2018) |

Upon the issuance of Executive Order No. 134, Tagalog was declared as basis of the National Language. On April 12, 1940, Executive No. 263 was issued ordering the teaching of the national language in all public and private schools in the country.[24]

Article XIV, Section 6 of the 1987 Constitution of the Philippines specifies, in part:

Subject to provisions of law and as the Congress may deem appropriate, the Government shall take steps to initiate and sustain the use of Filipino as a medium of official communication and as language of instruction in the educational system.[25]

Under Section 7, however:

The regional languages are the auxiliary official languages in the regions and shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction therein.[25]

In 2009, the Department of Education promulgated an order institutionalizing a system of mother-tongue based multilingual education ("MLE"), wherein instruction is conducted primarily in a student's mother tongue (one of the various regional Philippine languages) until at least grade three, with additional languages such as Filipino and English being introduced as separate subjects no earlier than grade two. In secondary school, Filipino and English become the primary languages of instruction, with the learner's first language taking on an auxiliary role.[26] After pilot tests in selected schools, the MLE program was implemented nationwide from School Year (SY) 2012–2013.[27][28]

Tagalog is the first language of a quarter of the population of the Philippines (particularly in Central and Southern Luzon) and the second language for the majority.[29]

Geographic distribution

[edit]In the Philippines

[edit]

This section may require copy editing for readability in some sentences about dialects. (September 2025) |

According to the 2020 census conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority, there were 109 million people living in the Philippines, where the vast majority have some basic level of understanding of the language. The Tagalog homeland, Katagalugan, covers roughly much of the central to southern parts of the island of Luzon — particularly in Aurora, Bataan, Batangas, Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna, Metro Manila, Nueva Ecija, Quezon, and Rizal. Tagalog is also spoken natively by inhabitants living on the islands of Marinduque and Mindoro, as well as Palawan to a lesser extent. Significant minorities of Tagalog (Filipino) speakers are found in the other Central Luzon provinces of Pampanga and Tarlac, Camarines Norte and Camarines Sur in Bicol Region, the Cordillera city of Baguio, southeast Pangasinan in Ilocos Region, and various parts of Mindanao especially in the island's urban areas. Tagalog or Filipino is also the predominant language of Cotabato City in Mindanao, making it the only place outside of Luzon with a native Tagalog-speaking or Filipino-speaking majority. It is also the main lingua franca in Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.[30]

According to the 2000 Philippine Census, approximately 96% of the household population who were able to attend school could speak Tagalog or Filipino;[31] and about 28% of the total population spoke it natively.[32]

The following regions and provinces of the Philippines are majority Tagalog-speaking, or also overlapping with being more accurately and specifically Filipino-speaking (from north to south):

- Cordillera Administrative Region

- Central Luzon Region

- Metro Manila (National Capital Region)

- Southern Luzon

- Southern Tagalog (Calabarzon and Mimaropa)

- Batangas

- Cavite

- Laguna

- Rizal

- Quezon

- Marinduque

- Occidental Mindoro

- Oriental Mindoro

- Romblon (While Romblomanon, Onhan, and Asi are the native languages of the province, Tagalog, or especially or more accurately and specifically as, through or in the form of a provincial variety of Filipino, is used as the lingua franca between the various language groups.)

- Palawan (Historically a non-Tagalog-speaking province, waves of cross-migration from various other regions, especially Calabarzon, has resulted in Tagalog, or especially or more accurately and specifically as, through or in the form of a provincial variety of Filipino, now being the main spoken language in Palawan.)

- Bicol Region (While the Bikol languages have traditionally been the majority languages in the following provinces, heavy Tagalog influence and migration has resulted in its significant presence in these provinces and in many communities, Tagalog is now the majority language.)

- Southern Tagalog (Calabarzon and Mimaropa)

- Bangsamoro

- Maguindanao del Norte and Maguindanao del Sur (While Maguindanao has traditionally been the majority language of these provinces, Tagalog, or especially or more accurately and specifically as, through or in the form of a regional variety of Filipino, is now the main language of "mother tongue" primary education (but here as the local and regional auxiliary official Tagalog language, rather than or instead of the national and official Filipino language) in the province, the majority language in the regional center of Cotabato City (either or both Tagalog or Filipino), and the lingua franca of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao or BARMM (mostly, mainly, majority or predominantly Filipino).)[33]

- Davao Region

- Metro Davao (While Cebuano is the majority language of the region, a linguistic phenomenon has developed whereby local residents have either shifted to Tagalog or Filipino, or significantly mix Tagalog terms and grammar into their Cebuano speech, or especially or more accurately and specifically in the form of a regional metropolitan variety of Filipino, because older generations speak Tagalog or Filipino to their children in home settings, and Cebuano is spoken in everyday settings, making Tagalog or Filipino the secondary lingua franca. Additionally, migrations from Tagalog-speaking provinces to the area are also a contributing factor.)

- Soccsksargen

- North Cotabato, South Cotabato and Sultan Kudarat (Despite Hiligaynon being the regional main lingua franca, migrations from Luzon and Visayas (including influx of migrants from Tagalog-speaking regions) to North Cotabato, South Cotabato and Sultan Kudarat has made Tagalog, or especially or more accurately and specifically, as, through or in the form of a regional variety of Filipino, the secondary lingua franca between various ethnolinguistic groups on everyday basis, especially those who cannot speak and understand Hiligaynon. Signages in the region are often written in Filipino or Tagalog. Additionally, the language is also used in administrative functions by the local government, in education and in local media, but especially or more accurately and specifically as, through or in the form of a regional variety of Filipino, and not and not as, through nor in the form of Tagalog nor its traditional Tagalog varieties.)

Tagalog speakers are found throughout the Philippines, but the standardized and official form called Filipino is used as the national language and lingua franca across the country, especially in education, government, and media.

Outside of the Philippines

[edit]

Tagalog serves as the common language among Overseas Filipinos, though its use overseas is usually limited to communication between Filipino ethnic groups. The largest concentration of Tagalog speakers outside the Philippines is found in the United States, wherein 2020, the United States Census Bureau reported (based on data collected in 2018) that it was the fourth most-spoken non-English language at home with over 1.7 million speakers, behind Spanish, French, and Chinese (with figures for Cantonese and Mandarin combined).[34]

A study based on data from the United States Census Bureau's 2015 American Consumer Survey shows that Tagalog is the most commonly spoken non-English language after Spanish in California, Nevada, and Washington states.[35]

Tagalog is one of three recognized languages in San Francisco, California, along with Spanish and Chinese, making all essential city services be communicated using these languages along with English.[36] Meanwhile, Tagalog and Ilocano (which is primarily spoken in northern Philippines) are among the non-official languages of Hawaii that its state offices and state-funded entities are required to provide oral and written translations to its residents.[37][38] Election ballots in Nevada include instructions written in Tagalog, which was first introduced in the 2020 United States presidential elections.[39]

Other countries with significant concentrations of overseas Filipinos and Tagalog speakers include Saudi Arabia with 938,490, Canada with 676,775, Japan with 313,588, United Arab Emirates with 541,593, Kuwait with 187,067, and Malaysia with 620,043.[40]

Dialects

[edit]

At present, no comprehensive dialectology has been done in the Tagalog-speaking regions, though there have been descriptions in the form of dictionaries and grammars of various Tagalog dialects. Ethnologue lists Manila, Lubang, Marinduque, Bataan (Western Central Luzon), Batangas, Bulacan (Eastern Central Luzon), Tanay-Paete (Rizal-Laguna), and Tayabas (Quezon)[2] as dialects of Tagalog; however, there appear to be four main dialects, of which the aforementioned are a part: Northern (exemplified by the Bulacan dialect), Central (including Manila), Southern (exemplified by Batangas), and Marinduque.

Some example of dialectal differences are:

- Many Tagalog dialects, particularly those in the south, preserve the glottal stop found after consonants and before vowels. This has been lost in Standard Tagalog, probably influenced by Spanish, where the glottal stop doesn't exist. For example, standard Tagalog ngayón (now, today), sinigáng (broth stew), gabí (night), matamís (sweet), are pronounced and written ngay-on, sinig-ang, gab-i, and matam-is in other dialects.

- In Teresian-Morong Tagalog, [ɾ] alternates with [d]. For example, bundók (mountain), dagat (sea), dingdíng (wall), isdâ (fish), and litid (joints) become bunrók, ragat, ringríng, isrâ, and litir, e.g. "sandók sa dingdíng" ("ladle on a wall" or "ladle on the wall", depending on the sentence) becoming "sanrók sa ringríng". However, exceptions are recent loanwords, and if the next consonant after a [d] is an [ɾ] (durog) or an [l] (dilà).

- In many southern dialects, the progressive aspect infix of -um- verbs is na-. For example, standard Tagalog kumakain (eating) is nákáin in Aurora, Quezon, and Batangas Tagalog. This is the butt of some jokes by other Tagalog speakers, for should a Southern Tagalog ask nákáin ka ba ng patíng? ("Do you eat shark?"), he would be understood as saying "Has a shark eaten you?" by speakers of the Manila Dialect.

- Some dialects have interjections which are considered a regional trademark. For example, the interjection ala e! usually identifies someone from Batangas as does hane?! in Rizal and Quezon provinces and akkaw in Aurora.

Perhaps the most divergent Tagalog dialects are those spoken in Marinduque.[41][42] Linguist Rosa Soberano identifies two dialects, western and eastern, with the former being closer to the Tagalog dialects spoken in the provinces of Batangas and Quezon.

One example is the verb conjugation paradigms. While some of the affixes are different, Marinduque also preserves the imperative affixes, also found in Visayan and Bikol languages, that have mostly disappeared from most Tagalog early 20th century; they have since merged with the infinitive.[43]

| Manileño Tagalog | Marinduqueño Tagalog | English |

|---|---|---|

| Susulat siná María at Esperanza kay Juan. | Másúlat da María at Esperanza kay Juan. | "María and Esperanza will write to Juan." |

| Mag-aaral siya sa Maynilà. | Gaaral siya sa Maynilà. | "[He/She] will study in Manila." |

| Maglutò ka na. | Paglutò. | "Cook now." |

| Kainin mo iyán. | Kaina yaan. | "Eat it." |

| Tinatawag tayo ni Tatay. | Inatawag nganì kitá ni Tatay. | "Father is calling us." |

| Tútulungan ba kayó ni Hilario? | Atulungan ga kamo ni Hilario? | "Is Hilario going to help you?" |

The Manila Dialect is the basis for the national language.

Outside of Luzon, a variety of Tagalog called Soccsksargen Tagalog (Sox-Tagalog, also called Kabacan Tagalog) is spoken in Soccsksargen, a southwestern region in Mindanao, as well as Cotabato City. This "hybrid" Tagalog dialect is a blend of Tagalog (including its dialects) with other languages where they are widely spoken and varyingly heard such as Hiligaynon (a regional lingua franca), Ilocano, Cebuano as well as Maguindanaon and other indigenous languages native to region, as a result of migration from Panay, Negros, Cebu, Bohol, Siquijor, Ilocandia, Cagayan Valley, Cordillera Administrative Region, Central Luzon, Calabarzon, Mindoro and Marinduque since the turn of 20th century, therefore making the region a melting pot of cultures and languages.[44][45][46][47]

Phonology

[edit]Tagalog has 21 phonemes: 16 are consonants and 5 are vowels. Native Tagalog words follow CV(C) syllable structure, though more complex consonant clusters are permitted in loanwords.[48][49][50][51][52][53]

Vowels

[edit]Tagalog has five vowels and four diphthongs.[48][49][50][51][52] Tagalog originally had three vowel phonemes, /a/, /i/, and /u/. Tagalog is now considered to have five vowel phonemes following the introduction of two marginal phonemes from Spanish, /o/ and /e/.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ⟨i⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | |

| Mid | ɛ ⟨e⟩ | o̞ ⟨o⟩ | |

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ |

- /a/ an open central unrounded vowel roughly similar to English "father"; in the middle of a word, a near-open central vowel similar to Received Pronunciation "cup"; or an open front unrounded vowel similar to Received Pronunciation or California English "hat"

- /ɛ/ an open-mid front unrounded vowel similar to General American English "bed"

- /i/ a close front unrounded vowel similar to English "machine"

- /o̞/ a mid back rounded vowel similar to General American English "soul" or Philippine English "forty"

- /u/ a close back rounded vowel similar to English "flute"

Nevertheless, simplification of pairs [o ~ u] and [ɛ ~ i] is likely to take place, especially in some Tagalog as second language, remote location and working class registers.

The four diphthongs are /aj/, /uj/, /aw/, and /iw/. Long vowels are not written apart from pedagogical texts, where an acute accent is used: á é í ó ú.[54]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ⟨i⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | |

| Near-close | ɪ ⟨i⟩ | ʊ ⟨u⟩ | |

| Close-mid | e ⟨e/i⟩ | o ⟨o/u⟩ | |

| Mid | ɛ̝ ⟨e⟩ | o̞ ⟨o⟩ | |

| Open-mid | ɛ ⟨e⟩ | ɔ ⟨o⟩ | |

| Near-open | ɐ ⟨a⟩ | ||

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ | ä ⟨a⟩ |

The table above shows all the possible realizations for each of the five vowel sounds depending on the speaker's origin or proficiency. The five general vowels are in bold.

Consonants

[edit]Below is a chart of Tagalog consonants. All the stops are unaspirated. The velar nasal occurs in all positions including at the beginning of a word. Loanword variants using these phonemes are italicized inside the angle brackets.

| Bilabial | Alv./Dental | Post-alv./ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | |||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | ʔ | |

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | (ts) | (tʃ) ⟨ts, tiy, ty⟩ | |||

| voiced | (dz) | (dʒ) ⟨dz, diy, dy⟩ | ||||

| Fricative | s | (ʃ) ⟨siy, sy, sh⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | |||

| Approximant | l | j ⟨y⟩ | w | |||

| Rhotic | ɾ ⟨r⟩ | |||||

- /k/ between vowels has a tendency to become [x] as in loch, German Bach, whereas in the initial position it has a tendency to become [kx], especially in the Manila dialect.

- Intervocalic /ɡ/ and /k/ tend to become [ɰ], as in Spanish agua, especially in the Manila dialect.

- /ɾ/ and /d/ were once allophones, and they still vary grammatically, with initial /d/ becoming intervocalic /ɾ/ in many words.[54]

- A glottal stop that occurs in pausa (before a pause) is omitted when it is in the middle of a phrase,[54] especially in the Metro Manila area. The vowel it follows is then lengthened. However, it is preserved in many other dialects.

- The /ɾ/ phoneme is an alveolar rhotic that has a free variation between a trill, a flap and an approximant ([r~ɾ~ɹ]).

- The /dʒ/ phoneme may become a consonant cluster [dd͡ʒ] in between vowels such as sadyâ [sɐdˈd͡ʒäʔ].

Glottal stop is not indicated.[54] Glottal stops are most likely to occur when:

- the word starts with a vowel, like aso (dog)

- the word includes a dash followed by a vowel, like mag-aral (study)

- the word has two vowels next to each other, like paano (how)

- the word starts with a prefix followed by a verb that starts with a vowel, like mag-aayos ([will] fix)

Stress and final glottal stop

[edit]Stress is a distinctive feature in Tagalog. Primary stress occurs on either the final or the penultimate syllable of a word. Vowel lengthening accompanies primary or secondary stress except when stress occurs at the end of a word.

Tagalog words are often distinguished from one another by the position of the stress or the presence of a final glottal stop. In formal or academic settings, stress placement and the glottal stop are indicated by a diacritic (tuldík) above the final vowel.[56] The penultimate primary stress position (malumay) is the default stress type and so is left unwritten except in dictionaries.

| Common spelling | Stressed non-ultimate syllable no diacritic |

Stressed ultimate syllable acute accent (´) |

Unstressed ultimate syllable with glottal stop grave accent (`) |

Stressed ultimate syllable with glottal stop circumflex accent (^) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| baba | [ˈbaba] baba ('father') | [baˈba] babá ('piggy back') | [ˈbabaʔ] babà ('chin') | [bɐˈbaʔ] babâ ('descend [imperative]') |

| baka | [ˈbaka] baka ('cow') | [bɐˈka] baká ('possible') | ||

| bata | [ˈbata] bata ('bath robe') | [bɐˈta] batá ('persevere') | [ˈbataʔ] batà ('child') | |

| bayaran | [bɐˈjaran] bayaran ('pay [imperative]') | [bɐjɐˈran] bayarán ('for hire') | ||

| labi | [ˈlabɛʔ]/[ˈlabiʔ] labì ('lips') | [lɐˈbɛʔ]/[lɐˈbiʔ] labî ('remains') | ||

| pito | [ˈpito] pito ('whistle') | [pɪˈto] pitó ('seven') | ||

| sala | [ˈsala] sala ('living room') | [saˈla] salá ('interweaving [of bamboo slats]') | [ˈsalaʔ] salà ('sin') | [sɐˈlaʔ] salâ ('filtered') |

Grammar

[edit]Writing system

[edit]Tagalog, like other Philippines languages today, is written using the Latin alphabet. Prior to the arrival of the Spanish in 1521 and the beginning of their colonization in 1565, Tagalog was written in an abugida—or alphasyllabary—called Baybayin. This system of writing gradually gave way to the use and propagation of the Latin alphabet as introduced by the Spanish. As the Spanish began to record and create grammars and dictionaries for the various languages of the Philippine archipelago, they adopted systems of writing closely following the orthographic customs of the Spanish language and were refined over the years. Until the first half of the 20th century, most Philippine languages were widely written in a variety of ways based on Spanish orthography.

In the late 19th century, a number of educated Filipinos began proposing for revising the spelling system used for Tagalog at the time. In 1884, Filipino doctor and student of languages Trinidad Pardo de Tavera published his study on the ancient Tagalog script Contribucion para el Estudio de los Antiguos Alfabetos Filipinos and in 1887, published his essay El Sanscrito en la lengua Tagalog which made use of a new writing system developed by him. Meanwhile, Jose Rizal, inspired by Pardo de Tavera's 1884 work, also began developing a new system of orthography (unaware at first of Pardo de Tavera's own orthography).[57] A major noticeable change in these proposed orthographies was the use of the letter ⟨k⟩ rather than ⟨c⟩ and ⟨q⟩ to represent the phoneme /k/.

In 1889, the new bilingual Spanish-Tagalog La España Oriental newspaper, of which Isabelo de los Reyes was an editor, began publishing using the new orthography stating in a footnote that it would "use the orthography recently introduced by ... learned Orientalis". This new orthography, while having its supporters, was also not initially accepted by several writers. Soon after the first issue of La España, Pascual H. Poblete's Revista Católica de Filipina began a series of articles attacking the new orthography and its proponents. A fellow writer, Pablo Tecson was also critical. Among the attacks was the use of the letters "k" and "w" as they were deemed to be of German origin and thus its proponents were deemed as "unpatriotic". The publishers of these two papers would eventually merge as La Lectura Popular in January 1890 and would eventually make use of both spelling systems in its articles.[58][57] Pedro Laktaw, a schoolteacher, published the first Spanish-Tagalog dictionary using the new orthography in 1890.[58]

In April 1890, Jose Rizal authored an article Sobre la Nueva Ortografia de la Lengua Tagalog in the Madrid-based periodical La Solidaridad. In it, he addressed the criticisms of the new writing system by writers like Pobrete and Tecson and the simplicity, in his opinion, of the new orthography. Rizal described the orthography promoted by Pardo de Tavera as "more perfect" than what he himself had developed.[58] The new orthography was, however, not broadly adopted initially and was used inconsistently in the bilingual periodicals of Manila until the early 20th century.[58] The revolutionary society Kataás-taasan, Kagalang-galang Katipunan ng̃ mg̃á Anak ng̃ Bayan or Katipunan made use of the k-orthography and the letter k featured prominently on many of its flags and insignias.[58]

In 1937, Tagalog was selected to serve as basis for the country's national language. In 1940, the Balarilâ ng Wikang Pambansâ (English: Grammar of the National Language) of grammarian Lope K. Santos introduced the Abakada alphabet. This alphabet consists of 20 letters and became the standard alphabet of the national language.[59][better source needed] The orthography as used by Tagalog would eventually influence and spread to the systems of writing used by other Philippine languages (which had been using variants of the Spanish-based system of writing). In 1987, the Abakada was dropped and replaced by the expanded Filipino alphabet.

Baybayin

[edit]Tagalog was written in an abugida (alphasyllabary) called Baybayin prior to the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines, in the 16th century. This particular writing system was composed of symbols representing three vowels and 14 consonants. Belonging to the Brahmic family of scripts, it shares similarities with the Old Kawi script of Java and is believed to be descended from the script used by the Bugis in Sulawesi.

Although it enjoyed a relatively high level of literacy, Baybayin gradually fell into disuse in favor of the Latin alphabet taught by the Spaniards during their rule.

There has been confusion of how to use Baybayin, which is actually an abugida, or an alphasyllabary, rather than an alphabet. Not every letter in the Latin alphabet is represented with one of those in the Baybayin alphasyllabary. Rather than letters being put together to make sounds as in Western languages, Baybayin uses symbols to represent syllables.

A "kudlít" resembling an apostrophe is used above or below a symbol to change the vowel sound after its consonant. If the kudlit is used above, the vowel is an "E" or "I" sound. If the kudlit is used below, the vowel is an "O" or "U" sound. A special kudlit was later added by Spanish missionaries in which a cross placed below the symbol to get rid of the vowel sound all together, leaving a consonant. Previously, the consonant without a following vowel was simply left out (for example, bundók being rendered as budo), forcing the reader to use context when reading such words.

Example:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latin alphabet

[edit]Abecedario

[edit]Until the first half of the 20th century, Tagalog was widely written in a variety of ways based on Spanish orthography consisting of 32 letters called 'ABECEDARIO' (Spanish for "alphabet").[60][61] The additional letters beyond the 26-letter English alphabet are: ch, ll, ng, ñ, n͠g / ñg, and rr.

| Majuscule | Minuscule | Majuscule | Minuscule |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | Ng | ng |

| B | b | Ñ | ñ |

| C | c | N͠g / Ñg | n͠g / ñg |

| Ch | ch | O | o |

| D | d | P | p |

| E | e | Q | q |

| F | f | R | r |

| G | g | Rr | rr |

| H | h | S | s |

| I | i | T | t |

| J | j | U | u |

| K | k | V | v |

| L | l | W | w |

| Ll | ll | X | x |

| M | m | Y | y |

| N | n | Z | z |

Abakada

[edit]When the national language was based on Tagalog, grammarian Lope K. Santos introduced a new alphabet consisting of 20 letters called Abakada in school grammar books called balarilâ.[62][63][full citation needed][64] The only letter not in the English alphabet is ng.

| Majuscule | Minuscule | Majuscule | Minuscule |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | N | n |

| B | b | Ng | ng |

| K | k | O | o |

| D | d | P | p |

| E | e | R | r |

| G | g | S | s |

| H | h | T | t |

| I | i | U | u |

| L | l | W | w |

| M | m | Y | y |

Revised alphabet

[edit]In 1987, the Department of Education, Culture and Sports issued a memo stating that the Philippine alphabet had changed from the Pilipino-Tagalog Abakada version to a new 28-letter alphabet[65][66] to make room for loans, especially family names from Spanish and English.[67] The additional letters beyond the 26-letter English alphabet are: ñ, ng.

| Majuscule | Minuscule | Majuscule | Minuscule |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | Ñ | ñ |

| B | b | Ng | ng |

| C | c | O | o |

| D | d | P | p |

| E | e | Q | q |

| F | f | R | r |

| G | g | S | s |

| H | h | T | t |

| I | i | U | u |

| J | j | V | v |

| K | k | W | w |

| L | l | X | x |

| M | m | Y | y |

| N | n | Z | z |

ng and mga

[edit]The genitive marker ng and the plural marker mga (e.g. Iyan ang mga damít ko. (Those are my clothes)) are abbreviations that are pronounced nang [naŋ] and mangá [mɐˈŋa]. Ng, in most cases, roughly translates to "of" (ex. Siyá ay kapatíd ng nanay ko. She is the sibling of my mother) while nang usually means "when" or can describe how something is done or to what extent (equivalent to the suffix -ly in English adverbs), among other uses.

- Nang si Hudas ay nadulás.—When Judas slipped.

- Gumising siya nang maaga.—He woke up early.

- Gumalíng nang todo si Juan dahil nag-ensayo siyá.—Juan greatly improved because he practiced.

In the first example, nang is used in lieu of the word noong (when; Noong si Hudas ay madulás). In the second, nang describes that the person woke up (gumising) early (maaga); gumising nang maaga. In the third, nang described up to what extent that Juan improved (gumalíng), which is "greatly" (nang todo). In the latter two examples, the ligature na and its variants -ng and -g may also be used (Gumising na maaga/Maagang gumising; Gumalíng na todo/Todong gumalíng).

The longer nang may also have other uses, such as a ligature that joins a repeated word:

- Naghintáy sila nang naghintáy.—They kept on waiting" (a closer calque: "They were waiting and waiting.")

pô/hô and opò/ohò

[edit]The words pô/hô originated from the word "Panginoon." and "Poon." ("Lord."). When combined with the basic affirmative Oo "yes" (from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *heqe), the resulting forms are opò and ohò.

"Pô" and "opò" are specifically used to denote a high level of respect when addressing older persons of close affinity like parents, relatives, teachers and family friends. "Hô" and "ohò" are generally used to politely address older neighbours, strangers, public officials, bosses and nannies, and may suggest a distance in societal relationship and respect determined by the addressee's social rank and not their age. However, "pô" and "opò" can be used in any case in order to express an elevation of respect.

- Example: "Pakitapon namán pô/hô yung basura." ("Please throw away the trash.")

Used in the affirmative:

- Ex: "Gutóm ka na ba?" "Opò/Ohò". ("Are you hungry yet?" "Yes.")

Pô/Hô may also be used in negation.

- Ex: "Hindi ko pô/hô alám 'yan." ("I don't know that.")

Vocabulary and borrowed words

[edit]Tagalog vocabulary is mostly of native Austronesian or Tagalog origin, such as most of the words that end with the diphthong -iw, (e.g. giliw) and words that exhibit reduplication (e.g. halo-halo, patpat, etc.). Besides inherited cognates, this also accounts for innovations in Tagalog vocabulary, especially traditional ones within its dialects. Tagalog has also incorporated many Spanish and English loanwords; the necessity of which increases in more technical parlance.

In precolonial times, Trade Malay was widely known and spoken throughout Maritime Southeast Asia, contributing a significant number of Malay vocabulary into the Tagalog language. Malay loanwords, identifiable or not, may often already be considered native as these have existed in the language before colonisation.

Tagalog also includes loanwords from Indian languages (Sanskrit and Tamil, mostly through Malay), Chinese languages (mostly Hokkien, followed by Cantonese, Mandarin, etc.), Japanese, Arabic and Persian.

English has borrowed some words from Tagalog, such as abaca, barong, balisong, boondocks, jeepney, Manila hemp, pancit, ylang-ylang, and yaya. Some of these loanwords are more often used in Philippine English.[68]

| Example | Definition |

|---|---|

| boondocks | meaning "rural" or "back country", borrowed through American soldiers stationed in the Philippines in the Philippine–American War as a corruption of the Tagalog word bundok, which means "mountain" |

| cogon | a type of grass, used for thatching, came from the Tagalog word kugon (a species of tall grass) |

| ylang-ylang | a tree whose fragrant flowers are used in perfumes |

| abacá | a type of hemp fiber made from a plant in the banana family, came from the Tagalog word abaká |

| Manila hemp | a light brown cardboard material used for folders and paper, usually made from abaca hemp, from Manila, the capital of the Philippines |

| capiz | a type of marine mollusc also known as a "windowpane oyster" used to make windows |

Tagalog has contributed several words to Philippine Spanish, like barangay (from balan͠gay, meaning barrio), the abacá, cogon, palay, dalaga etc.

Tagalog words of foreign origin

[edit]Taglish (Englog)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

Taglish and Englog are names given to a mix of English and Tagalog. The amount of English vs. Tagalog varies from the occasional use of English loan words to changing language in mid-sentence. Such code-switching is prevalent throughout the Philippines and in various languages of the Philippines other than Tagalog.[69]

Code-mixing also entails the use of foreign words that are "Filipinized" by reforming them using Filipino rules, such as verb conjugations. Users typically use Filipino or English words, whichever comes to mind first or whichever is easier to use.

Magshoshopping kamí sa mall. Sino ba ang magdadrive sa shopping center?

We will go shopping at the mall. Who will drive to the shopping center?

Urbanites are the most likely to speak like this.

The practice is common in television, radio, and print media as well.[69] Advertisements from companies like Wells Fargo, Wal-Mart, Albertsons, McDonald's and Western Union have contained Taglish.

Cognates with other Philippine languages

[edit]| Tagalog word | Meaning | Language of cognate | Spelling |

|---|---|---|---|

| bakit | why (from bakin + at) | Kapampangan | obakit |

| akyát | climb/step up | Kapampangan | ukyát/mukyát |

| bundók | mountain | Kapampangan | bunduk |

| at | and | Kapampangan Pangasinan |

at tan |

| aso | dog | Kapampangan and Maguindanaon Pangasinan, Ilocano, and Maranao |

asu aso |

| huwág | don't | Pangasinan | ag |

| tayo | we (inc.) | Pangasinan Ilocano Kapampangan Tausug Maguindanao Maranao Ivatan Ibanag Yogad Gaddang Tboli |

sikatayo datayo ikatamu kitaniyu tanu tano yaten sittam sikitam ikkanetam tekuy |

| itó, nitó | this, its | Ilocano Bicolano |

to iyó/ini |

| ng | of | Cebuano Hiligaynon Waray Kapampangan Pangasinan Bicolano Ilocano |

sa/og sang/sing han/hin/san/sin ning na kan/nin a |

| araw | sun; day | Visayan languages Kapampangan Pangasinan Bicolano (Central/East Miraya) and Ilocano Rinconada Bikol Ivatan Ibanag Yogad Gaddang Tboli |

adlaw aldo agew aldaw aldəw araw aggaw agaw aw kdaw |

| ang | definite article | Visayan languages (except Waray) Bicolano and Waray |

ang an |

Comparisons with Austronesian languages

[edit]Below is a chart of Tagalog and a number of other Austronesian languages comparing thirteen words.

| Tagalog | isá | dalawá | tatló | apat | tao | bahay | aso | niyóg | araw | bago | táyo | anó | apóy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tombulu (Minahasa) | esa | zua/rua | telu | epat | tou | walé | asu | po'po' | endo | weru | kai/kita | apa | api |

| Central Bikol | sarô | duwa | tulo | apat | tawo | harong | ayam | niyog | aldaw | bâgo | kita | ano | kalayo |

| East Miraya Bikol | əsad | əpat | taw | balay | ayam/ido | nuyog | unu/uno | kalayō | |||||

| Rinconada Bikol | darwā | tolō | tawō | baləy | ayam | noyog | aldəw | bāgo | kitā | onō | |||

| Waray | usá | duhá | tuló | upát | tawo | baláy | ayám/idô | lubí | adlaw | bag-o | kitá | anú/nano | kalayo |

| Kinaray-a | sara | darwa | ayam | niyog | |||||||||

| Akeanon | isaea/sambilog | daywa | ap-at | baeay | kaeayo | ||||||||

| Tausug | isa/hambuuk | duwa | tu | upat | tau | bay | iru' | niyug | ba-gu | kitaniyu | unu | kayu | |

| Maguindanao | isa | dua | telu | pat | walay | asu | gay | bagu | tanu | ngin | apuy | ||

| Maranao | dowa | t'lo | phat | taw | aso | neyog | gawi'e | bago | tano | tonaa | apoy | ||

| Kapampangan | isa/metung | adwa | atlu | apat | tau | bale | asu | ngungut | aldo | bayu | ikatamu | nanu | api |

| Pangasinan | sakey | dua/duara | talo/talora | apat/apatira | too | abong | aso | niyog | ageo/agew | balo | sikatayo | anto | pool |

| Ilocano | maysa | dua | tallo | uppat | tao | balay | niog | aldaw | baro | datayo | ania | apoy | |

| Ivatan | asa | dadowa | tatdo | apat | vahay | chito | niyoy | araw | va-yo | yaten | ango | ||

| Ibanag | tadday | dua | tallu | appa' | tolay | balay | kitu | niuk | aggaw | bagu | sittam | anni | afi |

| Yogad | tata | addu | appat | binalay | atu | iyyog | agaw | sikitam | gani | afuy | |||

| Gaddang | antet | addwa | tallo | balay | ayog | aw | bawu | ikkanetam | sanenay | ||||

| Tboli | sotu | lewu | tlu | fat | tau | gunu | ohu | lefo | kdaw | lomi | tekuy | tedu | ofih |

| Kadazan | iso | duvo | tohu | apat | tuhun | hamin | tasu | piasau | tadau | vagu | tokou | onu | tapui |

| Indonesian/Malay | satu | dua | tiga | empat | orang | rumah/balai | anjing | kelapa/nyiur | hari | baru/baharu | kita | apa | api |

| Javanese | siji | loro | telu | papat | uwong | omah/bale | asu | klapa/kambil | hari/dina/dinten | anyar/enggal | apa/anu | geni | |

| Acehnese | sa | duwa | lhèë | peuët | ureuëng | rumoh/balèë | asèë | u | uroë | barô | (geu)tanyoë | peuë | apuy |

| Lampung | sai | khua | telu | pak | jelema | lamban | asu | nyiwi | khani | baru | kham | api | apui |

| Buginese | se'di | dua | tellu | eppa' | tau | bola | kaluku | esso | idi' | aga | api | ||

| Batak | sada | tolu | opat | halak | jabu | biang | harambiri | ari | hita | aha | |||

| Minangkabau | ciek | duo | tigo | ampek | urang | rumah | anjiang | karambia | kito | apo | |||

| Tetum | ida | rua | tolu | haat | ema | uma | asu | nuu | loron | foun | ita | saida | ahi |

| Māori | tahi | toru | wha | tangata | whare | kuri | kokonati | ra | hou | taua | aha | ||

| Tuvaluan | tasi | lua | tolu | fá | toko | fale | moku | aso | fou | tāua | ā | afi | |

| Hawaiian | kahi | kolu | hā | kanaka | hale | 'īlio | niu | ao | hou | kākou | aha | ahi | |

| Banjarese | asa | dua | talu | ampat | urang | rumah | hadupan | kalapa | hari | hanyar | kita | apa | api |

| Malagasy | isa | roa | telo | efatra | olona | trano | alika | voanio | andro | vaovao | isika | inona | afo |

| Dusun | iso | duo | tolu | apat | tulun | walai | tasu | piasau | tadau | wagu | tokou | onu/nu | tapui |

| Iban | sa/san | duan | dangku | dangkan | orang | rumah | ukui/uduk | nyiur | hari | baru | kitai | nama | api |

| Melanau | satu | dua | telou | empat | apah | lebok | asou | nyior | lau | baew | teleu | apui |

Religious literature

[edit]

Religious literature remains one of the most dynamic components to Tagalog literature. The first Bible in Tagalog, then called Ang Biblia[70] ("the Bible") and now called Ang Dating Biblia[71] ("the Old Bible"), was published in 1905. In 1970, the Philippine Bible Society translated the Bible into modern Tagalog. Even before the Second Vatican Council, devotional materials in Tagalog had been in circulation. There are at least four circulating Tagalog translations of the Bible

- the Magandang Balita Biblia (a parallel translation of the Good News Bible), which is the ecumenical version

- the Bibliya ng Sambayanang Pilipino

- the 1905 Ang Biblia, used more by Protestants

- the Bagong Sanlibutang Salin ng Banal na Kasulatan (New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures), exclusive to the Jehovah's Witnesses

When the Second Vatican Council, (specifically the Sacrosanctum Concilium) permitted the universal prayers to be translated into vernacular languages, the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines was one of the first to translate the Roman Missal into Tagalog. The Roman Missal in Tagalog was published as early as 1982. In 2012, the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines revised the 41-year-old liturgy with an English version of the Roman Missal, and later translated it in the vernacular to several native languages in the Philippines.[72][73] For instance, in 2024, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Malolos uses the Tagalog translation of the Roman Missal entitled "Ang Aklat ng Mabuting Balita."[74]

Jehovah's Witnesses were printing Tagalog literature at least as early as 1941[75] and The Watchtower (the primary magazine of Jehovah's Witnesses) has been published in Tagalog since at least the 1950s. New releases are now regularly released simultaneously in a number of languages, including Tagalog. The official website of Jehovah's Witnesses also has some publications available online in Tagalog.[76] The revised bible edition, the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures, was released in Tagalog on 2019[77] and it is distributed without charge both printed and online versions.

Tagalog is quite a stable language, and very few revisions have been made to Catholic Bible translations. Also, as Protestantism in the Philippines is relatively young, liturgical prayers tend to be more ecumenical.

Example texts

[edit]Lord's Prayer

[edit]In Tagalog, the Lord's Prayer is known by its incipit, Amá Namin (literally, "Our Father").

Amá namin, sumasalangit Ka,

Sambahín ang ngalan Mo.

Mapasaamin ang kaharián Mo.

Sundín ang loób Mo,

Dito sa lupà, gaya nang sa langit.

Bigyán Mo kamí ngayón ng aming kakanin sa araw-araw,

At patawarin Mo kamí sa aming mga salà,

Para nang pagpápatawad namin,

Sa nagkakasalà sa amin;

At huwág Mo kamíng ipahintulot sa tuksô,

At iadyâ Mo kamí sa lahát ng masamâ.

[Sapagkát sa Inyó ang kaharián, at ang kapangyarihan,

At ang kaluwálhatian, ngayón, at magpakailanman.]

Amen.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

[edit]This is Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Pangkalahatáng Pagpapahayág ng Karapatáng Pantao)

- Tagalog (Latin)

Bawat tao'y isinilang na may layà at magkakapantáy ang tagláy na dangál at karapatán. Silá'y pinagkalooban ng pangangatwiran at budhî, at dapat magpálagayan ang isá't-isá sa diwà ng pagkákapatiran.

- Tagalog (Baybayin)

- English

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[78]

Numbers

[edit]Numbers (mga bilang/mga numero) in Tagalog follow two systems. The first consists of native Tagalog words and the other are Spanish-derived. (This may be compared to other East Asian languages, except with the second set of numbers borrowed from Spanish instead of Chinese.) For example, when a person refers to the number "seven", it can be translated into Tagalog as "pitó" or "siyete" (Spanish: siete).

| Number | Cardinal | Spanish-derived (Original Spanish) |

Ordinal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | sero / walâ (lit. 'null') | sero (cero) | – |

| 1 | isá | uno (uno) | una |

| 2 | dalawá [dalaua] | dos (dos) | pangalawá / ikalawá |

| 3 | tatló | tres (tres) | pangatló / ikatló |

| 4 | apat | kuwatro (cuatro) | pang-apat / ikaapat (In standard Filipino orthography, "ika" and the number-word are never hyphenated.) |

| 5 | limá | singko (cinco) | panlimá / ikalimá |

| 6 | anim | seis (seis) | pang-anim / ikaanim |

| 7 | pitó | siyete (siete) | pampitó / ikapitó |

| 8 | waló | otso (ocho) | pangwaló / ikawaló |

| 9 | siyám | nuwebe (nueve) | pansiyám / ikasiyám |

| 10 | sampû / pû (archaic) [sang puwo] | diyés (diez) | pansampû / ikasampû (or ikapû in some literary compositions) |

| 11 | labíng-isá | onse (once) | panlabíng-isá / pang-onse / ikalabíng-isá |

| 12 | labíndalawá | dose (doce) | panlabíndalawá / pandose / ikalabíndalawá |

| 13 | labíntatló | trese (trece) | panlabíntatló / pantrese / ikalabíntatló |

| 14 | labíng-apat | katorse (catorce) | panlabíng-apat / pangkatorse / ikalabíng-apat |

| 15 | labínlimá | kinse (quince) | panlabínlimá / pangkinse / ikalabínlimá |

| 16 | labíng-anim | disisais (dieciséis) | panlabíng-anim / pandyes-sais / ikalabíng-anim |

| 17 | labímpitó | disisiyete (diecisiete) | panlabímpitó / pandyes-syete / ikalabímpitó |

| 18 | labíngwaló | disiotso (dieciocho) | panlabíngwaló / pandyes-otso / ikalabíngwaló |

| 19 | labinsiyám / labins'yam / labingsiyam | disinuwebe (diecinueve) | panlabinsiyám / pandyes-nwebe / ikalabinsiyám |

| 20 | dalawampû | beynte (veinte) | pandalawampû / ikadalawampû (rare literary variant: ikalawampû) |

| 21 | dalawampú't isá | beynte y uno / beynte'y uno (veintiuno) | pang-dalawampú't isá / ikalawamapú't isá |

| 30 | tatlumpû | treynta (treinta) | pantatlumpû / ikatatlumpû (rare literary variant: ikatlumpû) |

| 40 | apatnapû | kuwarenta (cuarenta) | pang-apatnapû / ikaapatnapû |

| 50 | limampû | singkuwenta (cincuenta) | panlimampû / ikalimampû |

| 60 | animnapû | sesenta (sesenta) | pang-animnapû / ikaanimnapû |

| 70 | pitumpû | setenta (setenta) | pampitumpû / ikapitumpû |

| 80 | walumpû | otsenta (ochenta) | pangwalumpû / ikawalumpû |

| 90 | siyamnapû | nobenta (noventa) | pansiyamnapû / ikasiyamnapû |

| 100 | sándaán / daán | siyen (cien) | pan(g)-(i)sándaán / ikasándaán (rare literary variant: ikaisándaán) |

| 200 | dalawandaán | dosyentos (doscientos) | pandalawándaán / ikadalawandaan (rare literary variant: ikalawándaán) |

| 300 | tatlóndaán | tresyentos (trescientos) | pantatlóndaán / ikatatlondaan (rare literary variant: ikatlóndaán) |

| 400 | apat na raán | kuwatrosyentos (cuatrocientos) | pang-apat na raán / ikaapat na raán |

| 500 | limándaán | kinyentos (quinientos) | panlimándaán / ikalimándaán |

| 600 | anim na raán | seissiyentos (seiscientos) | pang-anim na raán / ikaanim na raán |

| 700 | pitondaán | setesyentos (setecientos) | pampitóndaán / ikapitóndaán (or ikapitóng raán) |

| 800 | walóndaán | otsosyentos (ochocientos) | pangwalóndaán / ikawalóndaán (or ikawalóng raán) |

| 900 | siyám na raán | nobesyentos (novecientos) | pansiyám na raán / ikasiyám na raán |

| 1,000 | sánlibo / libo | mil / uno mil (mil) | pan(g)-(i)sánlibo / ikasánlibo |

| 2,000 | dalawánlibo | dos mil (dos mil) | pangalawáng libo / ikalawánlibo |

| 10,000 | sánlaksâ / sampúng libo | diyes mil (diez mil) | pansampúng libo / ikasampúng libo |

| 20,000 | dalawanlaksâ / dalawampúng libo | beynte mil (veinte mil) | pangalawampúng libo / ikalawampúng libo |

| 100,000 | sangyutá / sandaáng libo | siyento mil (cien mil) | |

| 200,000 | dalawangyutá / dalawandaáng libo | dosyentos mil (doscientos mil) | |

| 1,000,000 | sang-angaw / sangmilyón | milyón (un millón) | |

| 2,000,000 | dalawang-angaw / dalawang milyón | dos milyónes (dos millones) | |

| 10,000,000 | sangkatì / sampung milyón | diyes milyónes (diez millones) | |

| 100,000,000 | sambahalà / sampúngkatì / sandaáng milyón | siyen milyónes (cien millones) | |

| 1,000,000,000 | sanggatós / sang-atós / sambilyón | bilyón / mil milyón (un billón (US),[79] mil millones, millardo[80]) | |

| 1,000,000,000,000 | sang-ipaw[citation needed] / santrilyón | trilyón / bilyón (un trillón (US),[81] un billón[79]) |

| Number | English | Spanish | Ordinal / Fraction / Cardinal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | first | primer, primero, primera | una / ikaisá |

| 2nd | second | segundo/a | ikalawá |

| 3rd | third | tercero/a | ikatló |

| 4th | fourth | cuarto/a | ikaapat |

| 5th | fifth | quinto/a | ikalimá |

| 6th | sixth | sexto/a | ikaanim |

| 7th | seventh | séptimo/a | ikapitó |

| 8th | eighth | octavo/a | ikawaló |

| 9th | ninth | noveno/a | ikasiyám |

| 10th | tenth | décimo/a | ikasampû |

| 1⁄2 | half | medio/a, mitad | kalahatì |

| 1⁄4 | one quarter | cuarto | kapat |

| 3⁄5 | three fifths | tres quintas partes | tatlóng-kalimá |

| 2⁄3 | two thirds | dos tercios | dalawáng-katló |

| 1+1⁄2 | one and a half | uno y medio | isá't kalahatì |

| 2+2⁄3 | two and two thirds | dos y dos tercios | dalawá't dalawáng-katló |

| 0.5 | zero point five | cero punto cinco, cero coma cinco,[82] cero con cinco | salapî / limá hinatì sa sampû |

| 0.05 | zero point zero five | cero punto cero cinco, cero coma cero cinco, cero con cero cinco | bagól / limá hinatì sa sandaán |

| 0.005 | zero point zero zero five | cero punto cero cero cinco, cero coma cero cero cinco, cero con cero cero cinco | limá hinatì sa sanlibo |

| 1.25 | one point two five | uno punto veinticinco, uno coma veinticinco, uno con veinticinco | isá't dalawampú't limá hinatì sa sampû |

| 2.025 | two point zero two five | dos punto cero veinticinco, dos coma cero veinticinco, dos con cero veinticinco | dalawá't dalawampú't limá hinatì sa sanlibo |

| 25% | twenty-five percent | veinticinco por ciento | dalawampú't-limáng bahagdán |

| 50% | fifty percent | cincuenta por ciento | limampúng bahagdán |

| 75% | seventy-five percent | setenta y cinco por ciento | pitumpú't-limáng bahagdán |

Months and days

[edit]Months and days in Tagalog are also localised forms of Spanish months and days. "Month" in Tagalog is buwán (also the word for moon) and "day" is araw (the word also means sun). Unlike Spanish, however, months and days in Tagalog are always capitalised.

| Month | Original Spanish | Tagalog (abbreviation) |

|---|---|---|

| January | enero | Enero (Ene.) |

| February | febrero | Pebrero (Peb.) |

| March | marzo | Marso (Mar.) |

| April | abril | Abríl (Abr.) |

| May | mayo | Mayo (Mayo) |

| June | junio | Hunyo (Hun.) |

| July | julio | Hulyo (Hul.) |

| August | agosto | Agosto (Ago.) |

| September | septiembre | Setyembre (Set.) |

| October | octubre | Oktubre (Okt.) |

| November | noviembre | Nobyembre (Nob.) |

| December | diciembre | Disyembre (Dis.) |

| Day | Original Spanish | Tagalog |

|---|---|---|

| Sunday | domingo | Linggó |

| Monday | lunes | Lunes |

| Tuesday | martes | Martes |

| Wednesday | miércoles | Miyérkules / Myérkules |

| Thursday | jueves | Huwebes / Hwebes |

| Friday | viernes | Biyernes / Byernes |

| Saturday | sábado | Sábado |

Time

[edit]Time expressions in Tagalog are also Tagalized forms of the corresponding Spanish. "Time" in Tagalog is panahón or oras.

| Time | English | Original Spanish | Tagalog |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 hour | one hour | una hora | Isáng oras |

| 2 min | two minutes | dos minutos | Dalawáng sandalî/minuto |

| 3 sec | three seconds | tres segundos | Tatlóng saglít/segundo |

| morning | mañana | Umaga | |

| afternoon | tarde | Hápon | |

| evening/night | noche | Gabí | |

| noon | mediodía | Tanghalì | |

| midnight | medianoche | Hatinggabí | |

| 1:00 am | one in the morning | una de la mañana | Ika-isá ng umaga |

| 7:00 pm | seven at night | siete de la noche | Ikapitó ng gabí |

| 1:15 | quarter past one one-fifteen |

una y cuarto | Kapat makalipas ika-isá Labínlimá makalipas ika-isá Apatnapú't-limá bago mag-ikalawá Tatlong-kapat bago mag-ikalawá |

| 2:30 | half past two two-thirty half-way to/of three |

dos y media | Kalahatì makalipas ikalawá Tatlumpû makalipas ikalawá Tatlumpû bago mag-ikatló Kalahatì bago mag-ikatló |

| 3:45 | three-forty-five quarter to/of four |

tres y cuarenta y cinco cuatro menos cuarto |

Tatlóng-kapat makalipas ikatló Apatnapú't-limá makalipas ikatló Labínlimá bago mag-ikaapat Kapat bago mag-ikaapat |

| 4:25 | four-twenty-five twenty-five past four |

cuatro y veinticinco | Dalawampú't-limá makalipas ikaapat Tatlumpú't-limá bago mag-ikaapat |

| 5:35 | five-thirty-five twenty-five to/of six |

cinco y treinta y cinco seis menos veinticinco |

Tatlumpú't-limá makalipas ikalimá Dalawampú't-limá bago mag-ikaanim |

Common phrases

[edit]| English | Tagalog (with Pronunciation) |

|---|---|

| Filipino | Pilipino [pɪlɪˈpino] |

| English | Inglés [ʔɪŋˈɡlɛs] |

| Tagalog | Tagálog [tɐˈɡaloɡ] |

| Spanish | Espanyol/Español/Kastila [ʔɛspɐnˈjol] |

| What is your name? | Anó ang pangálan ninyó/nilá*? (plural or polite) [ʔɐˈno: ʔaŋ pɐˈŋalan nɪnˈjo], Anó ang pangálan mo? (singular) [ʔɐˈno: ʔaŋ pɐˈŋalan mo] |

| How are you? | Kumustá [kʊmʊsˈta] (modern), Anó pô ang lagáy ninyó/nilá? (old use) [ʔɐˈno poː ʔɐŋ lɐˈgaɪ̯ nɪnˈjo] |

| Knock knock | Tao pô [ˈtɐʔo poʔ] |

| Good day! | Magandáng araw! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ ˈʔɐɾaʊ̯] |

| Good morning! | Magandáng umaga! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ ʔʊˈmaɡɐ] |

| Good noontime! (from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m.) | Magandáng tanghalì! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ tɐŋˈhalɛʔ] |

| Good afternoon! (from 1 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.) | Magandáng hapon! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ ˈhɐpon] |

| Good evening! | Magandáng gabí! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ ɡɐˈbɛ] |

| Good-bye | Paálam [pɐˈʔalɐm] |

| Please | Depending on the nature of the verb, either pakí- [pɐˈki] or makí- [mɐˈki] is attached as a prefix to a verb. Ngâ [ŋaʔ] is optionally added after the verb to increase politeness. (e.g. Pakipasa ngâ ang tinapay. ("Can you pass the bread, please?")) |

| Thank you | Salamat [sɐˈlamɐt] |

| This one | Itó [ʔɪˈto], sometimes pronounced [ʔɛˈto] (literally—"it", "this") |

| That one (close to addressee) | Iyán [ʔɪˈjan] |

| That one (far from speaker and addressee) | Iyón [ʔɪˈjon] |

| Here | Dito ['dito], heto ['hɛto], simplified to eto [ˈʔɛto] ("Here it is") |

| Right there | Diyán [dʒan], (h)ayán [(h)ɐˈjan], diyaán [dʒɐʔˈan] ("There it is") |

| Over there | Doón [doˈʔon], ayón [ɐˈjon] ("There it is") |

| How much? | Magkano? [mɐɡˈkano] |

| How many? | Ilán? [ʔɪˈlan] |

| Yes | Oo [ˈʔoʔo]

Opò [ˈʔopoʔ] or ohò [ˈʔohoʔ] (formal/polite form) |

| No | Hindî [hɪnˈdɛʔ] (at the end of a pause or sentence), often shortened to dî [dɛʔ]

Hindî pô [hɪnˈdiː poʔ] (formal/polite form) |

| I don't know | Hindî ko alám [hɪnˈdiː ko ʔɐˈlam]

Very informal: Ewan [ˈʔɛwɐn], archaic aywan [ʔaɪ̯ˈwan] (closest English equivalent: colloquial dismissive 'Whatever' or 'Dunno') |

| Sorry | Pasénsiya pô [pɐˈsɛnʃɐ poʔ] (literally from the word "patience") or paumanhín pô [pɐʔʊmɐnˈhin poʔ], patawad pô [pɐˈtawɐd poʔ] (literally—"asking your forgiveness") |

| Because | Kasí [kɐˈsɛ] or dahil ['dahɛl] |

| Hurry! | Dalî! [dɐˈliʔ], Bilís! [bɪˈlis] |

| Again | Mulî [mʊˈˈliʔ], ulít [ʔʊˈlɛt] |

| I don't understand | Hindî ko naíintindihán [hɪnˈdiː ko nɐˌʔiʔɪntɪndɪˈhan] or

Hindî ko naúunawáan [hɪnˈdiː ko nɐˌʔuʔʊnɐˈwaʔan] |

| What? | Anó? [ʔɐˈno] |

| Where? | Saán? [sɐˈʔan], Nasaán? [ˌnɐsɐˈʔan] (literally – "Where at?") |

| Why? | Bakit? [ˈbakɛt] |

| When? | Kailán? [kaɪ̯ˈlan], [kɐʔɪˈlan], or [ˈkɛlan] (literally—"In what order?/"At what count?") |

| How? | Paánó? [pɐˈʔano] (literally—"By what?") |

| Where's the bathroom? | Nasaán ang banyo? [ˌnɐsɐˈʔan ʔɐŋ ˈbanjo] |

| Generic toast | Mabuhay! [mɐˈbuhaɪ̯] (literally—"long live") |

| Do you speak English? | Marunong ka bang magsalitâ ng Inglés? [mɐˈɾunoŋ kɐ baŋ mɐɡsɐlɪˈtaː nɐŋ ʔɪŋˈɡlɛs]

Marunong pô ba kayóng magsalitâ ng Inglés? [mɐˈɾunoŋ poː ba kɐˈjoŋ mɐɡsɐlɪˈtaː nɐŋ ʔɪŋˈɡlɛs] (polite version for elders and strangers) |

| It is fun to live. | Masayá ang mabuhay! [mɐsɐˈja ʔɐŋ mɐˈbuhaɪ̯] or Masaya'ng mabuhay (contracted version) |

*Pronouns such as niyó (2nd person plural) and nilá (3rd person plural) are used on a single 2nd person in polite or formal language. See Tagalog grammar.

Proverbs

[edit]Ang hindî marunong lumingón sa pinánggalingan ay hindî makaráratíng sa paroroonan.

- (— José Rizal)

One who knows not how to look back to whence he came will never get to where he is going.

Unang kagát, tinapay pa rin.

First bite, still bread.

All fluff, no substance.

Tao ka nang humaráp, bilang tao kitáng haharapin.

You reach me as a human, I will treat you as a human and never act as a traitor.

(A proverb in Southern Tagalog that has made people aware of the significance of sincerity in Tagalog communities.)

Hulí man daw (raw) at magalíng, nakáhahábol pa rin.

If one is behind but capable, one will still be able to catch up.

Magbirô ka na sa lasíng, huwág lang sa bagong gising.

Make fun of someone drunk, if you must, but never one who has just awakened.

Aanhín pa ang damó kung patáy na ang kabayò?

What use is the grass if the horse is already dead?

Ang sakít ng kalingkingan, damdám ng buóng katawán.

The pain in the pinkie is felt by the whole body.

In a group, if one goes down, the rest follow.

Nasa hulí ang pagsisisi.

Regret is always in the end.

Pagkáhabà-habà man ng prusisyón, sa simbahan pa rin ang tulóy.

The procession may stretch on and on, but it still ends up at the church.

(In romance: refers to how certain people are destined to be married. In general: refers to how some things are inevitable, no matter how long you try to postpone it.)

Kung 'dî mádaán sa santóng dasalan, daanin sa santóng paspasan.

If it cannot be got through holy prayer, get it through blessed force.

(In romance and courting: santóng paspasan literally means 'holy speeding' and is a euphemism for sexual intercourse. It refers to the two styles of courting by Filipino boys: one is the traditional, protracted, restrained manner favored by older generations, which often featured serenades and manual labor for the girl's family; the other is upfront seduction, which may lead to a slap on the face or a pregnancy out of wedlock. The second conclusion is known as pikot or what Western cultures would call a 'shotgun marriage'. This proverb is also applied in terms of diplomacy and negotiation.)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Tagalog language at Ethnologue (28th ed., 2025)

- ^ a b Manuel, E. Arsenio (1971). A Lexicographic Study of Tayabas Tagalog of Quezon Province. Diliman Review. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "The Morphology of Sox-Tagalog". medium.com. July 9, 2024. Retrieved November 3, 2024.

- ^ Donoso, Isaac (2019). "Letra de Meca: Jawi Script in the Tagalog Region During the 16th Century". Journal of Al-Tamaddun. 14 (1). San Vicente del Raspeig: Universidad de Alicante: 89–103. doi:10.22452/JAT.vol14no1.8.

- ^ According to the OED and Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary Archived January 21, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Lewis, M. P.; Simons, G. F.; Fennig, C. D. (2014). "Tagalog". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Archived from the original on December 12, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ Zorc, R. David Paul (1977). The Bisayan Dialects of the Philippines: Subgrouping and Reconstruction. Pacific Linguistics, Series C, No. 44. Canberra: The Australian National University. doi:10.15144/PL-C44. hdl:1885/146594. ISBN 9780858831575.

- ^ Blust, Robert (1991). "The Greater Central Philippines Hypothesis". Oceanic Linguistics. 30 (2): 73–129. doi:10.2307/3623084. JSTOR 3623084.

- ^ Postma, Anton (1992). "The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary". Philippine Studies. 40 (2): 183–203. JSTOR 42633308. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Noceda, Juan José de; Sanlucar, Pedro de (2013) [1860]. Vocabulario de la lengua tagala. Maynila: Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino. p. iv.

- ^ Noceda, Juan José de; Sanlucar, Pedro de (1860). Vocabulario de la lengua tagala: compuesto por varios religiosos doctos y graves, y coordinado (in Spanish). Manila: Ramirez y Giraudier.

- ^ Noceda, Juan José de; Sanlucar, Pedro de (2013) [1860]. Vocabulario de la lengua tagala. Maynila: Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino.

- ^ Spieker-Salazar, Marlies (1992). "A Contribution to Asian Historiography: European Studies of Philippines Languages from the 17th to the 20th Century". Archipel. 44 (1): 183–202. doi:10.3406/arch.1992.2861.

- ^ Cruz, Hermenegildo (1906). Kun Sino ang Kumathâ ng̃ "Florante": Kasaysayan ng̃ Búhay ni Francisco Baltazar at Pag-uulat nang Kanyang Karunung̃a't Kadakilaan (in Tagalog). Maynilà: Librería "Manila Filatélico" – via Google Books.

- ^ 1897 Constitution of Biak-na-Bato, Article VIII. November 1897. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022 – via The Corpus Juris.

- ^ Porter, David (2019). Language and National Identity in the Philippines. University of California Press.

- ^ UNESCO (2021). Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education in the Philippines. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- ^ "1935 Philippine Constitution (amended), Article XIV, Section 3". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2022 – via Official Gazette.

- ^ a b c Quezon, Manuel L. (December 30, 1937). Speech of His Excellency Manuel L. Quezon President of the Philippines on Filipino National Language (PDF) (Speech). Malacañan Palace, Manila. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2010 – via quezon.ph.

- ^ a b c d e Gonzalez, Andrew (1998). "The Language Planning Situation in the Philippines" (PDF). Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 19 (5, 6): 487–488. doi:10.1080/01434639808666365. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 22, 2006.

- ^ "1973 Philippine Constitution, Article XV, Sections 2–3". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on June 25, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2022 – via Official Gazette.

- ^ "Mga Probisyong Pangwika sa Saligang-Batas". wika.pbworks.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ^ Tan, Nigel (August 7, 2014). "What the PH Constitutions Say About the National Language". Rappler. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Espiritu, Clemencia (April 29, 2015). "Filipino Language in the Curriculum". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ a b "1987 Philippine Constitution, Article XIV, Sections 6–9". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2022 – via Official Gazette.

- ^ Department of Education (2009). Order No. 74 (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2012.

- ^ DO 16, s. 2012. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2018 – via deped.gov.ph.

- ^ Dumlao, Artemio (May 21, 2012). "K+12 to Use 12 Mother Tongues". Philstar Global. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Philippine Census, 2000. Table 11. Household Population by Ethnicity, Sex and Region: 2000

- ^ McKenna, Thomas M. (1998). Muslim Rulers and Rebels: Everyday Politics and Armed Separatism in the Southern Philippines. Berkeley: University of California Press. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2020 – via UC Press E-Books Collection, 1982–2004.

- ^ "Educational Characteristics of the Filipinos (Results from the 2000 Census of Population and Housing, NSO)". National Statistics Office. March 18, 2005. Archived from the original on January 27, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ "Philippines: Population Expected to Reach 100 Million Filipinos in 14 Years (Results from the 2000 Census of Population and Housing, NSO)" (Press release). National Statistics Office. October 16, 2002. Archived from the original on January 28, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ Maulana, Nash (August 3, 2014). "Filipino or Tagalog Now Dominant Language of Teaching for Maguindanaons". Inquirer.net. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ "Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over for United States: 2014-2018". census.gov. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020.

- ^ "Study: Tagalog California's Most Commonly Spoken Foreign Language After Spanish". CBS Los Angeles. July 7, 2017. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Tagalog Certified As Third Language To Be Used In SF City Services Communications". CBS San Francisco. April 2, 2014. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Office of Language Access: Find a Law". Hawaii.gov. State of Hawaii. Archived from the original on September 7, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ "Office of Language Access: "Free Interpreter Help" in Multi-Languages". Hawaii.gov. State of Hawaii. Archived from the original on September 7, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ "Tagalog Was on the Ballot for the First Time in Nevada". CNN. February 12, 2020. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ "Distribution on Filipinos Overseas". dfa.gov.ph. Archived from the original on April 27, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ Soberano, Ros (1980). The Dialects of Marinduque Tagalog. Pacific Linguistics, Series B, No. 69. Canberra: The Australian National University. doi:10.15144/PL-B69. hdl:1885/144521. ISBN 9780858832169.

- ^ "My Marinduque | Travel Blog".

- ^ "Salita Blog: Tagalog verbs". March 30, 2007.

- ^ "On Writing in Hybrid Language: An Interview with Gerald Galindez". August 3, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ Pagsusuri sa Varayti at Varyasyon ng Sox-Tagalog: Isang Komparatibong Pag-aaral.

- ^ Leceña, Hanna A. (2023). "Mga Tula sa Filipino-SOX na Zines: Túngo sa Pagpapakilala ng Multilingguwal at Multikultural na Komunidad sa Timog Mindanao". Philippine High School for the Arts, Makiling los Baños. 26 (1): 10.

- ^ Cordial, J. (July 9, 2024). "The Morphology of Sox-Tagalog". Medium. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. (2011). "Tagalog". In Adelaar, Alexander; Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. (eds.). The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar. Routledge (published 2005). pp. 351–352. ISBN 978-0-415-68153-7.

- ^ a b Rubino, Carl R. Galvez (2002). Tagalog-English, English-Tagalog Dictionary. Hippocrene Books, Inc. pp. 351–352. ISBN 0-7818-0961-4.

- ^ a b Guzman, Videa (2001). "Tagalog". In Garry, Jane; Rubino, Carl (eds.). Facts about the world's languages : an encyclopedia of the world's major languages, past and present. New England Publishing Associates. p. 704. ISBN 0-8242-0970-2.

- ^ a b Quilis, Antonio (1985). "A Comparison of the Phonemic Systems of Spanish and Tagalog". In Jankowsky, Kurt R. (ed.). Scientific and Humanistic Dimensions of Language: Festschrift for Robert Lado. Benjamins. pp. 241–243. ISBN 90-272-2013-1.

- ^ a b Schachter, Paul; Otanes, Fe T. (1972). Tagalog Reference Grammar. University of California Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-520-01776-5.

- ^ Zamar, Sheila (October 31, 2022). "Phonology and Spelling". Filipino: An Essential Grammar. Routledge (published 2023). pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-1-138-82628-1.

- ^ a b c d e Tagalog (2005). Keith Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- ^ Moran, Steven; McCloy, Daniel; Wright, Richard (2012). "Revisiting population size vs. phoneme inventory size". Language. 88 (4): 877–893. doi:10.1353/lan.2012.0087. hdl:1773/25269. ISSN 1535-0665. S2CID 145423518. Archived from the original on April 27, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ Himmelmann, Nikolaus (2005). "Tagalog". In Adelaar, K. Alexander; Himmelmann, Nikolaus (eds.). The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar. London: Routledge. pp. 350–376.

- ^ a b "Is 'K' a Foreign Agent? Orthography and Patriotism: Accusations of Foreign-ness of the Revista Católica de Filipina". espanito.com. Archived from the original on December 13, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas, Megan C. (2007). "K is for De-Kolonization: Anti-Colonial Nationalism and Orthographic Reform". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 49 (4): 938–967. doi:10.1017/S0010417507000813. S2CID 144161531.

- ^ "Ebolusyon ng Alpabetong Filipino". wika.pbworks.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ Gómez Rivera, Guillermo (April 10, 2001). "The Evolution of the Native Tagalog Alphabet". Emanila News. Archived from the original on September 19, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ Signey, Richard C. (2005). "The Evolution and Disappearance of the "Ğ" in Tagalog Orthography since the 1593 Doctrina Christiana". Philippine Journal of Linguistics. 36 (1–2): 1–10. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ Võ, Linda Trinh; Bonus, Rick, eds. (2002). Contemporary Asian American Communities: Intersections and Divergences. Temple University Press. pp. 96, 100. ISBN 978-1-56639-938-8.

- ^ "Philippine Journal of Education". Philippine Journal of Education. 50: 556. 1971.

- ^ Martin, Perfecto T. (1986). Diksiyunaryong Adarna: Mga Salita at Larawan para sa Bata. Children's Communication Center. ISBN 978-971-12-1118-9.

- ^ Trinh & Bonus 2002, pp. 96, 100

- ^ Perdon, Renato (2005). Pocket Tagalog Dictionary: Tagalog-English/English-Tagalog. Periplus Editions. pp. vi–vii. ISBN 978-0-7946-0345-8.

- ^ Clyne, Michael, ed. (1997). Undoing and Redoing Corpus Planning. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 317. ISBN 3-11-015509-5.

- ^ "English Words Used in Filipino". FilipinoPod101.com Blog. May 13, 2021. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Bautista, Maria Lourdes S. (June 2004). "Tagalog-English Code Switching as a Mode of Discourse" (PDF). Asia Pacific Education Review. 5 (2). Education Research Institute, Seoul National University: 226–231. doi:10.1007/BF03024960. ISSN 1598-1037. OCLC 425894528. S2CID 145684166. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ Worth, Roland H. (2008). Biblical Studies on the Internet: A Resource Guide (2nd ed.). McFarland. p. 43.

- ^ "Genesis 1". biblehub.com. Bible Hub. Archived from the original on August 18, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ "Manila Archdiocese starts seminars for new translation of Roman Missal". GMA Integrated News. January 16, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ Aning, Jerome (November 25, 2011). "Church revises Roman Missal". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ "Sandigan". Roman Catholic Diocese of Malolos. January 1, 2024. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ 2003 Yearbook of Jehovah's Witnesses. Watch Tower Society. p. 155.