Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Plot (narrative)

View on Wikipedia

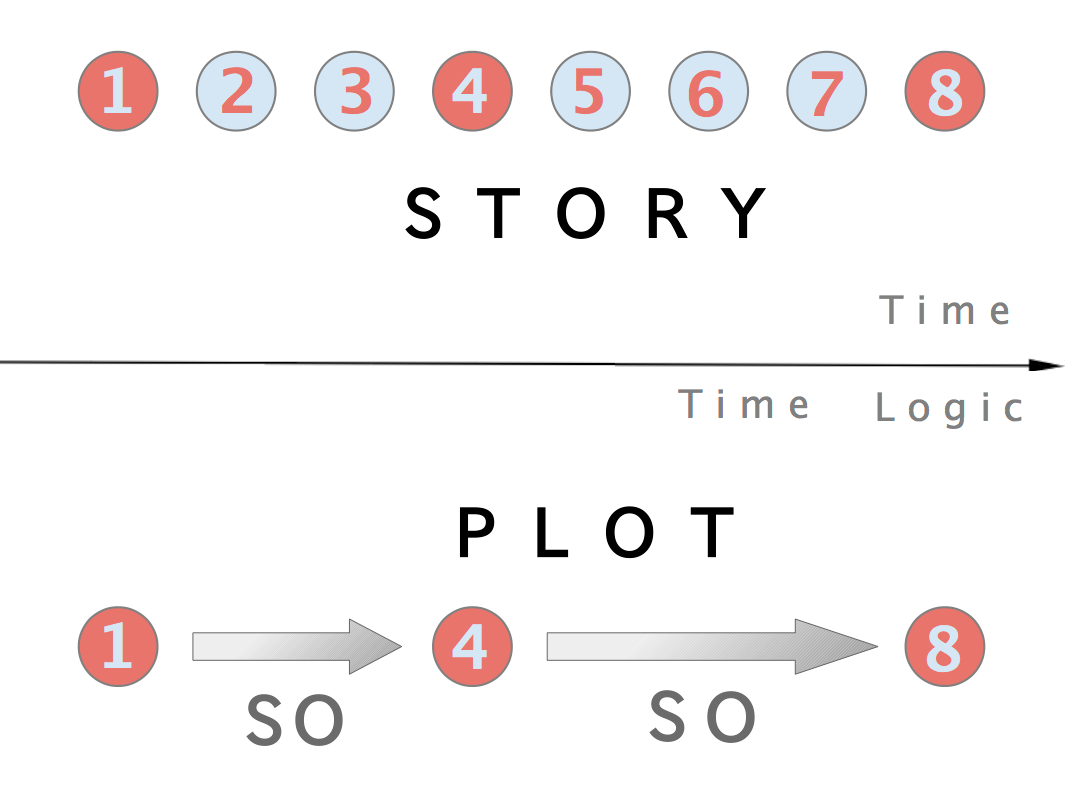

In a literary work, film, or other narrative, the plot is the mapping of events in which each one (except the final) affects at least one other through the principle of cause-and-effect. The causal events of a plot can be thought of as a selective collection of events from a narrative, all linked by the connector "and so". Simple plots, such as in a traditional ballad, can be linearly sequenced, but plots can form complex interwoven structures, with each part sometimes referred to as a subplot.

Plot is similar in meaning to the term storyline.[2][3] In the narrative sense, the term highlights important points which have consequences within the story, according to American science fiction writer Ansen Dibell.[1] The premise sets up the plot, the characters take part in events, while the setting is not only part of, but also influences, the final story. An imbroglio can convolute the plot based on a misunderstanding.

The term plot can also serve as a verb, as part of the craft of writing, referring to the writer devising and ordering story events. (A related meaning is a character's planning of future actions in the story.) However, in common usage (e.g., a "film plot"), the word plot more often refers to a narrative summary, or story synopsis.

Definition

[edit]Early 20th-century English novelist E. M. Forster described plot as the cause-and-effect relationship between events in a story. According to Forster, "The king died, and then the queen died, is a story, while The king died, and then the queen died of grief, is a plot."[4][5][6]

Teri Shaffer Yamada, Ph.D., of CSULB, agrees that a plot does not include memorable scenes within a story that do not relate directly to other events but only "major events that move the action in a narrative."[7] For example, in the 1997 film Titanic, when Rose climbs on the railing at the front of the ship and spreads her hands as if she's flying, this scene is memorable but does not directly influence other events, so it may not be considered as part of the plot. Another example of a memorable scene that is not part of the plot occurs in the 1980 film The Empire Strikes Back, when Han Solo is frozen in carbonite.[1]

Fabula and syuzhet

[edit]The literary theory of Russian Formalism in the early 20th century divided a narrative into two elements: the fabula (фа́була) and the syuzhet (сюже́т). A fabula is the chronology of the fictional world, whereas a syuzhet is a perspective or plot thread of those events. Formalist followers eventually translated the fabula/syuzhet to the concept of story/plot. This definition is usually used in narratology, in parallel with Forster's definition. The fabula (story) is what happened in chronological order. In contrast, the syuzhet (plot) means a unique sequence of discourse that was sorted out by the (implied) author. That is, the syuzhet can consist of picking up the fabula events in non-chronological order; for example, fabula is ⟨a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, ..., an⟩, syuzhet is ⟨a5, a1, a3⟩.

The Russian formalist, Viktor Shklovsky, viewed the syuzhet as the fabula defamiliarized. Defamiliarization or "making strange," a term Shklovsky coined and popularized, upends familiar ways of presenting a story, slows down the reader's perception, and makes the story appear unfamiliar.[8] Shklovsky cites Lawrence Sterne's Tristram Shandy as an example of a fabula that has been defamiliarized.[9] Sterne uses temporal displacements, digressions, and causal disruptions (for example, placing the effects before their causes) to slow down the reader's ability to reassemble the (familiar) story. As a result, the syuzhet "makes strange" the fabula.

Examples

[edit]

Cinderella

[edit]A story orders events from beginning to end in a time sequence.[1]

Consider the following events in the European folk tale "Cinderella":

- The prince searches for Cinderella with the glass shoe

- Cinderella's sisters try the shoe on themselves but it does not fit them

- The shoe fits Cinderella's foot so the prince finds her

The first event is causally related to the third event, while the second event, though descriptive, does not directly impact the outcome. As a result, according to Ansen Dibell, the plot can be described as the first event "and so" the last event, while the story can be described by all three events in order.

The Wizard of Oz

[edit]

Fiction-writing coach Steve Alcorn says that the main plot elements of the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz are easy to find, and include:[10]

- A tornado picks up a house and drops it on a witch in a fantastical land

- A girl and her dog meet three interesting traveling companions

- Another witch sends them on a mission

- They melt a third witch with a bucket of water

Concepts

[edit]Structure and treatment

[edit]Dramatic structure is the philosophy by which the story is split and how the story is thought of. This can vary by ethnicity, region and time period. This can be applied to books, plays, and films. Philosophers/critics who have discussed story structure include Aristotle, Horace, Aelius Donatus, Gustav Freytag, Kenneth Thorpe Rowe, Lajos Egri, Syd Field, and others. Some story structures are so old that the originator cannot be found, such as Ta'zieh.

Often in order to sell a script, the plot structure is made into what is called a treatment. This can vary based on locality, but for Europe and European Diaspora, the three-act structure is often used. The components of this structure are the set-up, the confrontation and the resolution. Acts are connected by two plot points or turning points, with the first turning point connecting Act I to Act II, and the second connecting Act II to Act III. The conception of the three-act structure has been attributed to American screenwriter Syd Field who described plot structure in this tripartite way for film analysis.

Furthermore, in order to sell a book within the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia, often the plot structure is split into a synopsis. Again the plot structure may vary by genre or drama structure used.

Aristotle

[edit]Many scholars have analyzed dramatic structure, beginning with Aristotle in his Poetics (c. 335 BC).

In his Poetics, a theory about tragedies, the Greek philosopher Aristotle put forth the idea the play should imitate a single whole action. "A whole is what has a beginning and middle and end" (1450b27).[11] He split the play into two acts: complication and denouement.[12] He mainly used Sophocles to make his argument about the proper dramatic structure of a play.

Two types of scenes are of special interest: the reversal, which throws the action in a new direction, and the recognition, meaning the protagonist has an important revelation.[13] Reversals should happen as a necessary and probable cause of what happened before, which implies that turning points need to be properly set up.[13] He ranked the order of importance of the play to be: Chorus, Events, Diction, Character, Spectacle.[12] And that all plays should be able to be performed from memory, long and easy to understand.[14] He was against character-centric plots stating “The Unity of a Plot does not consist, as some suppose, in its having one man as its subject.”[15] He was against episodic plots.[16] He held that discovery should be the high point of the play and that the action should teach a moral that is reenforced by pity, fear and suffering.[17] The spectacle, not the characters themselves would give rise to the emotions.[18] The stage should also be split into “Prologue, Episode, Exode, and a choral portion, distinguished into Parode and Stasimon...“[19]

Unlike later, he held that the morality was the center of the play and what made it great. Unlike popular belief, he did not come up with the three act structure popularly known.

Gustav Freytag

[edit]

The German playwright and novelist Gustav Freytag wrote Die Technik des Dramas,[21] a definitive study of the five-act dramatic structure, in which he laid out what has come to be known as Freytag's pyramid.[22] Under Freytag's pyramid, the plot of a story consists of five parts:[23][20]

- Exposition (originally called introduction)

- Rising action (rise)

- Climax

- Falling action (return or fall)

- Catastrophe, denouement, resolution, or revelation[24] or "rising and sinking". Freytag is indifferent as to which of the contending parties justice favors; in both groups, good and evil, power and weakness, are mingled.[25]

A drama is then divided into five parts, or acts, which some refer to as a dramatic arc: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and catastrophe. Freytag extends the five parts with three moments or crises: the exciting force, the tragic force, and the force of the final suspense. The exciting force leads to the rising action, the tragic force leads to the falling action, and the force of the final suspense leads to the catastrophe. Freytag considers the exciting force to be necessary but the tragic force and the force of the final suspense are optional. Together, they make the eight component parts of the drama.[20]

In making his argument, he attempts to retcon much of the Greeks and Shakespeare by making opinions of what they meant, but did not actually say.[26]

He argued for tension created through contrasting emotions, but did not actively argue for conflict.[27] He argued that character comes first in plays.[28] He also set up the groundwork for what would later be called the inciting incident.[29]

Overall, Freytag argued the center of a play is emotionality and the best way to get that emotionality is to put contrasting emotions back to back. He laid some of the foundations for centering the hero, unlike Aristotle. He is popularly attributed to have stated conflict at the center of his plays, but he argues actively against continuing conflict.[30]

Freytag defines the parts as:

- Introduction

- The setting is fixed in a particular place and time, the mood is set, and characters are introduced. A backstory may be alluded to. Exposition can be conveyed through dialogues, flashbacks, characters' asides, background details, in-universe media, or the narrator telling a back-story.[31]

- Rise

- An exciting force begins immediately after the exposition (introduction), building the rising action in one or several stages toward the point of greatest interest. These events are generally the most important parts of the story since the entire plot depends on them to set up the climax and ultimately the satisfactory resolution of the story itself.[32]

- Climax

- The climax is the turning point, which changes the protagonist's fate. If things were going well for the protagonist, the plot will turn against them, often revealing the protagonist's hidden weaknesses.[33] If the story is a comedy, the opposite state of affairs will ensue, with things going from bad to good for the protagonist, often requiring the protagonist to draw on hidden inner strengths. A plot with an exciting climax is said to be climactic. A disappointing scene is instead called anticlimactic.[34]

- Return or Fall

- During the Return, the hostility of the counter-party beats upon the soul of the hero. Freytag lays out two rules for this stage: the number of characters be limited as much as possible, and the number of scenes through which the hero falls should be fewer than in the rising movement. The falling action may contain a moment of final suspense: Although the catastrophe must be foreshadowed so as not to appear as a non sequitur, there could be for the doomed hero a prospect of relief, where the final outcome is in doubt.[35]

- Catastrophe

- The catastrophe (Katastrophe in the original)[36] is where the hero meets his logical destruction. Freytag warns the writer not to spare the life of the hero.[37] More generally, the final result of a work's main plot has been known in English since 1705 as the denouement (UK: /deɪˈnuːmɒ̃, dɪ-/, US: /ˌdeɪnuːˈmɒ̃/;[38]). It comprises events from the end of the falling action to the actual ending scene of the drama or narrative. Conflicts are resolved, creating normality for the characters and a sense of catharsis, or release of tension and anxiety, for the reader. Etymologically, the French word dénouement (French: [denumɑ̃]) is derived from the word dénouer, "to untie", from nodus, Latin for "knot." It is the unraveling or untying of the complexities of a plot.[39]

Plot devices

[edit]A plot device is a means of advancing the plot in a story. It is often used to motivate characters, create urgency, or resolve a difficulty. This can be contrasted with moving a story forward with dramatic technique; that is, by making things happen because characters take action for well-developed reasons. An example of a plot device would be when the cavalry shows up at the last moment and saves the day in a battle. In contrast, an adversarial character who has been struggling with himself and saves the day due to a change of heart would be considered dramatic technique.

Familiar types of plot devices include the deus ex machina, the MacGuffin, the red herring, and Chekhov's gun.

Plot outline

[edit]A plot outline is a prose telling of a story which can be turned into a screenplay. Sometimes it is called a "one page" because of its length. In comics, the roughs refer to a stage in the development where the story has been broken down very loosely in a style similar to storyboarding in film development. This stage is also referred to as storyboarding or layouts. In Japanese manga, this stage is called the nēmu (ネーム, pronounced like the English word "name"). The roughs are quick sketches arranged within a suggested page layout. The main goals of roughs are to:

- lay out the flow of panels across a page

- ensure the story successfully builds suspense

- work out points of view, camera angles, and character positions within panels

- serve as a basis for the next stage of development, the "pencil" stage, where detailed drawings are produced in a more polished layout which will, in turn, serve as the basis for the inked drawings.

In fiction writing, a plot outline gives a list of scenes. Scenes include events, character(s) and setting. Plot, therefore, shows the cause and effect of these things put together. The plot outline is a rough sketch of this cause and effect made by the scenes to lay out a "solid backbone and structure" to show why and how things happened as they did.

Plot summary

[edit]A plot summary is a brief description of a piece of literature that explains what happens. In a plot summary, the author and title of the book should be referred to and it is usually no more than a paragraph long while summarizing the main points of the story.[40][41]

A-Plot

[edit]An A-Plot is a cinema and television term referring to the plotline that drives the story. This does not necessarily mean it is the most important, but rather the one that forces most of the action.

See also

[edit]- Monomyth

- Mythos (Aristotle)

- Narrative structure

- Narrative thread

- Plot drift

- Plot hole

- Premise (narrative)

- Robert McKee

- Scene and sequel

- Theme (narrative)

- The Seven Basic Plots, a book by Christopher Booker

- The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations, which is Georges Polti's categorization of every dramatic situation that might occur in a story or performance.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Ansen Dibell, Ph.D. (1999-07-15). Plot. Elements of Fiction Writing. Writer's Digest Books. pp. 5 f. ISBN 978-0-89879-946-0.

Plot is built of significant events in a given story – significant because they have important consequences. Taking a shower isn't necessarily plot... Let's call them incidents ... Plot is the things characters do, feel, think or say, that make a difference to what comes afterward.

- ^ "Definition of plot". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- ^ "Definition of storyline". Oxford Dictionaries. 2014-08-09. Archived from the original on 2014-08-09. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- ^ Prince, Gerald (2003-12-01). A Dictionary of Narratology (Revised ed.). University of Nebraska Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8032-8776-1.

- ^ Wales, Katie (2011-05-19). A Dictionary of Stylistics. Longman Linguistics (3 ed.). Routledge. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-4082-3115-9.

- ^ Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. Mariner Books. (1956) ISBN 978-0156091800

- ^ Ali, Asgar (2022). "CHAPTER 22 STRUCTURE OF THE PLOT IN ENGLISH LITERATURE". In DEVENDRA KUMAR GORA, YASHASWINI (ed.). INTRODUCTION TO ENGLISH LITERATURE AND DRAMA (PDF). Jersey City: Alexis Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-64532-485-0. Retrieved 1 September 2025.

- ^ Victor Shklovsky, "Art as Technique," in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, 2nd ed., trans. Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 3-24.

- ^ Shklovsky, "Sterne's Tristram Shandy: Stylistic Commentary" in Russian Formalist Criticism, 25-57.

- ^ Steve Alcorn. "Know the Difference Between Plot and Story". Tejix. Archived from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- ^ Aristotle (1932) [c. 335 BCE]. "Aristotle, Poetics, section 1450b". Aristotle in 23 Volumes. Vol. 23. Translated by W.H. Fyfe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 2023-01-25 – via www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ a b Aristotle. "18 (Aristotle on the Art of Poetry)". The Poetics. Translated by Ingram Bywater. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 2023-01-25 – via www.authorama.com.

- ^ a b Aristotle (2008) [c. 335 BCE]. "XI". Aristotle's Poetics. Translated by S. H. Butcher. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Aristotle. "7 (Aristotle on the Art of Poetry)". The Poetics. Translated by Ingram Bywater. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 2023-01-25 – via www.authorama.com.

- ^ Aristotle. "8 (Aristotle on the Art of Poetry)". The Poetics. Translated by Ingram Bywater. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 2023-01-25 – via www.authorama.com.

- ^ Aristotle. "10 (Aristotle on the Art of Poetry)". The Poetics. Translated by Ingram Bywater. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 2023-01-25 – via www.authorama.com.

- ^ Aristotle. "11 (Aristotle on the Art of Poetry)". The Poetics. Translated by Ingram Bywater. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 2023-01-25 – via www.authorama.com.

- ^ Aristotle. "14". The Poetics. Translated by Ingram Bywater. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021.

- ^ Aristotle. "12 (Aristotle on the Art of Poetry)". The Poetics. Translated by Ingram Bywater. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Freytag (1900, p. 115)

- ^ Freytag, Gustav (1900). Technique of the Drama: an Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art. Translated by Elias J. MacEwan (Third ed.). Chicago: Scott, Foresman.

- ^ University of South Carolina (2006). The Big Picture Archived October 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ University of Illinois: Department of English (2006). Freytag's Triangle Archived July 16, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Freytag, Gustav (1863). Die Technik des Dramas (in German). Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ^ Freytag (1900, pp. 104–105)

- ^ Freytag. pp. 25, 41, 75, 98, 188–189

- ^ Freytag. p. 80–81

- ^ Freytag. p. 90

- ^ Freytag. pp. 94–95

- ^ Freytag p. 29

- ^ Freytag (1900, pp. 115–121)

- ^ Freytag (1900, pp. 125–128)

- ^ Freytag (1900, pp. 128–130)

- ^ "Climactic: Definition, Meaning, & Synonyms". June 23, 2018.

- ^ Freytag (1900, pp. 133–135)

- ^ Freytag. p 137

- ^ Freytag (1900, pp. 137–140)

- ^ "dénouement". Cambridge Dictionary.

- ^ Merriam-Webster. (n.d.) Denoument. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved May 29, 2023 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/denouement

- ^ Stephen V. Duncan (2006). A Guide to Screenwriting Success: Writing for Film and Television. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-0-7425-5301-9.

- ^ Steven Espinoza; Kathleen Fernandez-Vander Kaay; Chris Vander Kaay (20 August 2019). We All Know How This Ends: The Big Book of Movie Plots. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78627-527-1.

References

[edit]- Freytag, Gustav (1900) [Copyright 1894], Freytag's Technique of the Drama, An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art by Dr. Gustav Freytag: An Authorized Translation From the Sixth German Edition by Elias J. MacEwan, M.A. (3rd ed.), Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company, LCCN 13-283

- Mack, Maynard; Knox, Bernard M. W.; McGaillard, John C.; et al., eds. (1985), The Norton Anthology of World Masterpieces, vol. 1 (5th ed.), New York: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-95432-3

Further reading

[edit]- Obstfeld, Raymond (2002). Fiction First Aid: Instant Remedies for Novels, Stories and Scripts. Cincinnati, OH: Writer's Digest Books. ISBN 1-58297-117-X.

- Foster-Harris (1960). The Basic Formulas of Fiction. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ASIN B0007ITQBY.

- Polking, K (1990). Writing A to Z. Cincinnati, OH: Writer's Digest Books. ISBN 0-89879-435-8.

External links

[edit]- The "Basic" Plots In Literature, Information on the most common divisions of the basic plots, from the Internet Public Library organization.

- Plot Definition, meaning and examples

- The Minimal Plot, on cyclic structures of the basic plots by Yevgeny Slavutin and Vladimir Pimonov.