Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Part of a series on |

| Old Norse |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Norse history and culture |

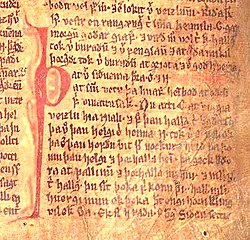

Sagas are prose stories and histories, composed in Iceland and to a lesser extent elsewhere in Scandinavia.

The most famous saga-genre is the sagas of Icelanders, which feature Viking voyages, migration to Iceland, and feuds between Icelandic families. However, sagas' subject matter is diverse, including pre-Christian Scandinavian legends; saints and bishops both from Scandinavia and elsewhere; Scandinavian kings and contemporary Icelandic politics; and chivalric romances either translated from Continental European languages or composed locally.

Sagas originated in the Middle Ages, but continued to be composed in the ensuing centuries. Whereas the dominant language of history-writing in medieval Europe was Latin, sagas were composed in the vernacular: Old Norse and its later descendants, primarily Icelandic.

While sagas are written in prose, they share some similarities with epic poetry, and often include stanzas or whole poems in alliterative verse embedded in the text.

Etymology and meaning of saga

[edit]The main meanings of the Old Norse word saga (plural sǫgur) are 'what is said, utterance, oral account, notification' and the sense used in this article: '(structured) narrative, story (about somebody)'.[1] It is cognate with the English words say and saw (in the sense 'a saying', as in old saw), and the German Sage; but the modern English term saga was borrowed directly into English from Old Norse by scholars in the eighteenth century to refer to Old Norse prose narratives.[2][3]

The word continues to be used in this sense in the modern Scandinavian languages: Icelandic saga (plural sögur), Faroese søga (plural søgur), Norwegian soge (plural soger), Danish saga (plural sagaer), and Swedish saga (plural sagor). It usually also has wider meanings such as 'history', 'tale', and 'story'. It can also be used of a genre of novels telling stories spanning multiple generations, or to refer to saga-inspired fantasy fiction.[4] Swedish folksaga means folk tale or fairy tale, while konstsaga is the Swedish term for a fairy tale by a known author, such as Hans Christian Andersen. In Swedish historiography, the term sagokung, "saga king", is intended to be ambiguous, as it describes the semi-legendary kings of Sweden, who are known only from unreliable sources.[5]

Genres

[edit]

Norse sagas are generally classified as follows.

Kings' sagas

[edit]Kings' sagas (konungasögur) are of the lives of Scandinavian kings. They were composed in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries. A pre-eminent example is Heimskringla, probably compiled and composed by Snorri Sturluson. These sagas frequently quote verse, invariably occasional and praise poetry in the form of skaldic verse.

Sagas of Icelanders and short tales of Icelanders

[edit]The Icelanders' sagas (Íslendingasögur), sometimes also called "family sagas" in English, are purportedly (and sometimes actually) stories of real events, which usually take place from around the settlement of Iceland in the 870s to the generation or two following the conversion of Iceland to Christianity in 1000. They are noted for frequently exhibiting a realistic style.[6]: 101, 105–7 It seems that stories from these times were passed on in oral form until they eventually were recorded in writing as Íslendingasögur, whose form was influenced both by these oral stories and by literary models in both Old Norse and other languages.[6]: 112–14 The majority — perhaps two thirds of the medieval corpus — seem to have been composed in the thirteenth century, with the remainder in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.[6]: 102 These sagas usually span multiple generations and often feature everyday people (e.g. Bandamanna saga) and larger-than-life characters (e.g. Egils saga).[6]: 107–12 Key works of this genre have been viewed in modern scholarship as the highest-quality saga-writing. While primarily set in Iceland, the sagas follow their characters' adventures abroad, for example in other Nordic countries, the British Isles, northern France and North America.[7][6]: 101 Some well-known examples include Njáls saga, Laxdæla saga and Grettis saga.

The material of the short tales of Icelanders (þættir or Íslendingaþættir) is similar to Íslendinga sögur, in shorter form, often preserved as episodes about Icelanders in the kings' sagas.

Like kings' sagas, when sagas of Icelanders quote verse, as they often do, it is almost invariably skaldic verse.

Contemporary sagas

[edit]Contemporary sagas (samtíðarsögur or samtímasögur) are set in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Iceland, and were written soon after the events they describe. Most are preserved in the compilation Sturlunga saga, from around 1270–80, though some, such as Arons saga Hjörleifssonar are preserved separately.[8] The verse quoted in contemporary sagas is skaldic verse.

According to historian Jón Viðar Sigurðsson, "Scholars generally agree that the contemporary sagas are rather reliable sources, based on the short time between the events and the recording of the sagas, normally twenty to seventy years... The main argument for this view on the reliability of these sources is that the audience would have noticed if the saga authors were slandering and not faithfully portraying the past."[9]

Legendary sagas

[edit]Legendary sagas (fornaldarsögur) blend remote history, set on the Continent before the settlement of Iceland, with myth or legend. Their aim is usually to offer a lively narrative and entertainment. They often portray Scandinavia's pagan past as a proud and heroic history. Some legendary sagas quote verse — particularly Vǫlsunga saga and Heiðreks saga — and when they do it is invariably Eddaic verse.

Some legendary sagas overlap generically with the next category, chivalric sagas.[10]: 191

Chivalric sagas

[edit]Chivalric sagas (riddarasögur) are translations of Latin pseudo-historical works and French chansons de geste as well as Icelandic compositions in the same style. Norse translations of Continental romances seem to have begun in the first half of the thirteenth century;[11]: 375 Icelandic writers seem to have begun producing their own romances in the late thirteenth century, with production peaking in the fourteenth century and continuing into the nineteenth.[10]

While often translated from verse, sagas in this genre almost never quote verse, and when they do it is often unusual in form: for example, Jarlmanns saga ok Hermanns contains the first recorded quotation of a refrain from an Icelandic dance-song,[12] and a metrically irregular riddle in Þjalar-Jóns saga.[13]

Saints' and bishops' sagas

[edit]Saints' sagas (heilagra manna sögur) and bishops' sagas (biskupa sögur) are vernacular Icelandic translations and compositions, to a greater or lesser extent influenced by saga-style, in the widespread genres of hagiography and episcopal biographies. The genre seems to have begun in the mid-twelfth century.[14]

History

[edit]

Icelandic sagas are based on oral traditions and much research has focused on what is real and what is fiction within each tale. The accuracy of the sagas is often hotly disputed.

Most of the medieval manuscripts which are the earliest surviving witnesses to the sagas were taken to Denmark and Sweden in the seventeenth century, but later returned to Iceland. Classical sagas were composed in the thirteenth century. Scholars once believed that these sagas were transmitted orally from generation to generation until scribes wrote them down in the thirteenth century. However, most scholars now believe the sagas were conscious artistic creations, based on both oral and written tradition. A study focusing on the description of the items of clothing mentioned in the sagas concludes that the authors attempted to create a historic "feel" to the story, by dressing the characters in what was at the time thought to be "old fashioned clothing". However, this clothing is not contemporary with the events of the saga as it is a closer match to the clothing worn in the 12th century.[15] It was only recently (start of 20th century) that the tales of the voyages to North America (modern day Canada) were authenticated.[16]

Most sagas of Icelanders take place in the period 930–1030, which is called söguöld (Age of the Sagas) in Icelandic history. The sagas of kings, bishops, contemporary sagas have their own time frame. Most were written down between 1190 and 1320, sometimes existing as oral traditions long before, others are pure fiction, and for some we do know the sources: the author of King Sverrir's saga had met the king and used him as a source.[17]

While sagas are generally anonymous, a distinctive literary movement in the 14th century involves sagas, mostly on religious topics, with identifiable authors and a distinctive Latinate style. Associated with Iceland's northern diocese of Hólar, this movement is known as the North Icelandic Benedictine School (Norðlenski Benediktskólinn).[18]

The vast majority of texts referred to today as "sagas" were composed in Iceland. One exception is Þiðreks saga, translated/composed in Norway; another is Hjalmars och Hramers saga, a post-medieval forgery composed in Sweden. While the term saga is usually associated with medieval texts, sagas — particularly in the legendary and chivalric saga genres — continued to be composed in Iceland on the pattern of medieval texts into the nineteenth century.[19][10]: 193–94

Explanations for saga writing

[edit]Icelanders produced a high volume of literature relative to the size of the population. Historians have proposed various theories for the high volume of saga writing.

Early, nationalist historians argued that the ethnic characteristics of the Icelanders were conducive to a literary culture, but these types of explanations have fallen out of favor with academics in modern times.[20] It has also been proposed that the Icelandic settlers were so prolific at writing in order to capture their settler history. Historian Gunnar Karlsson does not find that explanation reasonable though, given that other settler communities have not been as prolific as the early Icelanders were.[20]

Pragmatic explanations were once also favoured: it has been argued that a combination of readily available parchment (due to extensive cattle farming and the necessity of culling before winter) and long winters encouraged Icelanders to take up writing.[20]

More recently, Icelandic saga-production has been seen as motivated more by social and political factors.

The unique nature of the political system of the Icelandic Commonwealth created incentives for aristocrats to produce literature,[21][22] offering a way for chieftains to create and maintain social differentiation between them and the rest of the population.[22][23] Gunnar Karlsson and Jesse Byock argued that the Icelanders wrote the Sagas as a way to establish commonly agreed norms and rules in the decentralized Icelandic Commonwealth by documenting past feuds, while Iceland's peripheral location put it out of reach of the continental kings of Europe and that those kings could therefore not ban subversive forms of literature.[20] Because new principalities lacked internal cohesion, a leader typically produced Sagas "to create or enhance amongst his subjects or followers a feeling of solidarity and common identity by emphasizing their common history and legends".[21] Leaders from old and established principalities did not produce any Sagas, as they were already cohesive political units.[21]

Later (late thirteenth- and fourteenth-century) saga-writing was motivated by the desire of the Icelandic aristocracy to maintain or reconnect links with the Nordic countries by tracing the ancestry of Icelandic aristocrats to well-known kings and heroes to which the contemporary Nordic kings could also trace their origins.[22][23]

Editions and translations

[edit]The corpus of Old Norse sagas is gradually being edited in the Íslenzk fornrit series, which covers all the Íslendingasögur and a growing range of other ones. Where available, the Íslenzk fornrit edition is usually the standard one.[6]: 117 The standard edition of most of the chivalric sagas composed in Iceland is by Agnete Loth.[24][10]: 192

A list, intended to be comprehensive, of translations of Icelandic sagas is provided by the National Library of Iceland's Bibliography of Saga Translations.

Popular culture

[edit]Many modern artists working in different creative fields have drawn inspiration from the sagas. Among some well-known writers, for example, who adapted saga narratives in their works are Poul Anderson, Laurent Binet, Margaret Elphinstone, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Gunnar Gunnarsson, Henrik Ibsen, Halldór Laxness, Ottilie Liljencrantz, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, George Mackay Brown, William Morris, Adam Oehlenschläger, Robert Louis Stevenson, August Strindberg, Rosemary Sutcliff, Esaias Tegnér, J.R.R. Tolkien, and William T. Vollmann.[25]

See also

[edit]References and notes

[edit]- ^ Dictionary of Old Norse Prose/Ordbog over det norrøne prosasprog (Copenhagen: [Arnamagnæan Commission/Arnamagnæanske kommission], 1983–), s.v. '1 saga sb. f.' Archived 18 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "saw, n.2. Archived 2 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine", OED Online, 1st edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, December 2019).

- ^ "saga, n.1. Archived 2 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine", OED Online, 1st edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, December 2019).

- ^ J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings series was translated into Swedish by Åke Ohlmarks with the title Sagan om ringen: "The Saga of the Ring". (The 2004 translation was titled Ringarnas herre, a literal translation from the original.) Icelandic journalist Þorsteinn Thorarensen (1926–2006) translated the work as Hringadróttins saga meaning "Saga of the Lord of the Rings".

- ^ "Untitled Document". www.fotevikensmuseum.se. Archived from the original on 12 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Vésteinn Ólason, 'Family Sagas', in A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture, ed. by Rory Mcturk (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), pp. 101–18.

- ^ "heimskringla.no". www.heimskringla.no. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "Sagas of Contemporary History (Blackwell Reference Online)". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ Sigurdsson, Jon Vidar (2017). Viking Friendship: The Social Bond in Iceland and Norway, C. 900–1300. Cornell University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-5017-0848-0. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d Matthew, Driscoll, 'Late Prose Fiction (Lygisögur)', in A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture, ed. by Rory McTurk (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), pp. 190–204.

- ^ Jürg Glauser, 'Romance (Translated Riddarasögur)', in A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture, ed. by Rory McTurk (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), pp. 190–204.

- ^ Aðalheiður Guðmundsdóttir, 'How Icelandic Legends Reflect the Prohibition on Dancing', ARV, 61 (2006), 25–52.

- ^ 'Þjalar-Jóns saga', trans. by Philip Lavender, Leeds Studies in English, n.s. 46 (2015), 73–113 (p. 88 n. 34).

- ^ Margaret Cormack, 'Christian Biography', in A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture, ed. by Rory Mcturk (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), pp. 27–42.

- ^ "Clothing In Norse Literature (HistoriskeDragter.dk)". Archived from the original on 23 November 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ Strange Footprints on the Land (Author: Irwin, Constance publisher: Harper & Row, 1980) ISBN 0-06-022772-9

- ^ "Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages (The Skaldic Project)". Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "AM 657 a-b 4to | Handrit.is". handrit.is. Archived from the original on 12 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ Matthew James Driscoll, The Unwashed Children of Eve: The Production, Dissemination and Reception of Popular Literature in Post-Reformation Iceland (Enfield Lock: Hisarlik Press, 1997).

- ^ a b c d "Sagnfræðingafélag Íslands » Archive » Hlaðvarp: Gunnar Karlsson: Ísland sem jaðarsvæði evrópskrar miðaldamenningar". Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Kristinsson, Axel (1 June 2003). "Lords and Literature: The Icelandic Sagas as Political and Social Instruments". Scandinavian Journal of History. 28 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/03468750310001192. ISSN 0346-8755. S2CID 143890402.

- ^ a b c Eriksen, Anne; Sigurðsson, Jón Viðar (1 January 2010). Negotiating Pasts in the Nordic Countries: Interdisciplinary Studies in History and Memory. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 9789185509331.

- ^ a b Tulinius, Torfi (2002). The Matter of the North. Odense University Press. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ Agnete Loth, ed., Late Medieval Icelandic Romances, Editiones Arnamagaeanae, series B, 20–24, 5 vols (Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1962–65).

- ^ "Database of medieval Icelandic saga literary adaptations". Christopher W. E. Crocker. 23 February 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

Sources

[edit]Primary:

Other:

- Clover, Carol J. et al. Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A critical guide (University of Toronto Press, 2005) ISBN 978-0802038234

- Gade, Kari Ellen (ed.) Poetry from the Kings' Sagas 2 From c. 1035 to c. 1300 (Brepols Publishers. 2009) ISBN 978-2-503-51897-8

- Gordon, E. V. (ed) An Introduction to Old Norse (Oxford University Press; 2nd ed. 1981) ISBN 978-0-19-811184-9

- Jakobsson, Armann; Fredrik Heinemann (trans) A Sense of Belonging: Morkinskinna and Icelandic Identity, c. 1220 (Syddansk Universitetsforlag. 2014) ISBN 978-8776748456

- Jakobsson, Ármann Icelandic sagas (The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages 2nd Ed. Robert E. Bjork. 2010) ISBN 9780199574834

- McTurk, Rory (ed) A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005) ISBN 978-0631235026

- Ross, Margaret Clunies The Cambridge Introduction to the Old Norse-Icelandic Saga (Cambridge University Press, 2010) ISBN 978-0-521-73520-9

- Thorsson, Örnólfur The Sagas of Icelanders (Penguin. 2001) ISBN 978-0141000039

- Whaley, Diana (ed.) Poetry from the Kings' Sagas 1 From Mythical Times to c. 1035 (Brepols Publishers. 2012) ISBN 978-2-503-51896-1

Further reading

[edit]In Norwegian:

- Haugen, Odd Einar Handbok i norrøn filologi (Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, 2004) ISBN 978-82-450-0105-1

External links

[edit]- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). pp. 1000–1001.

- Icelandic Saga Database – The Icelandic sagas in the original old Norse along with translations into many languages

- Old Norse Prose and Poetry

- The Icelandic sagas at Netútgáfan

Definition and Etymology

Meaning and Usage

A saga is a prose narrative, typically composed in Old Norse during the medieval period in Iceland, that recounts historical, legendary, or fictional events centered on the lives of families, heroes, or rulers.[5] These works, emerging primarily in the 13th and 14th centuries, blend factual accounts with artistic reconstruction to depict Viking Age exploits, settlements, and interpersonal conflicts.[6] The term "saga" itself derives from Old Norse, meaning "something said" or "a narrative," reflecting its roots in spoken storytelling.[7] Unlike eddic poetry, which consists of mythological verse focused on gods and cosmic events, or continental romances emphasizing chivalric ideals and overt fantasy, sagas prioritize realistic prose with naturalistic dialogue and sparse supernatural elements, particularly in narratives about Icelandic families.[2] This style conveys character through external actions and reported speech rather than internal monologue, creating a sense of historical authenticity even in legendary tales.[7] In medieval Icelandic society, sagas served dual purposes as entertainment and historical record-keeping, preserving communal memory and fostering cultural identity amid Christianization and political changes.[8] They originated from oral traditions but were committed to writing to document genealogies, feuds, and legal disputes, offering insights into social structures like honor and kinship.[5] Structurally, sagas often feature episodic plots spanning multiple generations, as seen in works like Brennu-Njáls saga, which extends over approximately 400 pages to chronicle interconnected family conflicts, voyages, and resolutions through arbitration.[7]Linguistic Origins

The term saga derives from Old Norse saga (plural sǫgur), denoting "what is said," "utterance," or "story," and is directly linked to the verb segja ("to say, tell"). This connection reflects the narrative's origin in oral transmission, where stories were accounts of spoken words or events.[9] The word traces its deeper roots to Proto-Germanic sagǭ ("saying, story"), which stems from the Proto-Indo-European root sekʷ- ("to say, utter"). This ancient root gave rise to cognates across Indo-European languages, including Old English secgan (whence Modern English "say") and related forms in other branches emphasizing verbal expression or declaration.[10] In medieval Old Norse texts, saga initially encompassed any spoken narrative or account, often tied to legal, historical, or personal testimonies preserved through oral tradition. By the 13th century, as written literature flourished in Iceland and Norway, the term evolved to specifically designate extended prose compositions, shifting from ephemeral speech to durable written records that captured collective memory.[11] Latin and Christian influences shaped saga nomenclature in ecclesiastical settings, where the term adapted to describe translated hagiographies and biblical narratives, such as heilagra manna sögur ("sagas of holy men"), integrating native prose forms with imported Latin vitae and sermones to convey religious doctrine.Historical Context

Oral Traditions Preceding Written Sagas

In the Viking Age, spanning roughly the 9th to 11th centuries, oral traditions in Scandinavia served as the primary means of preserving historical, legal, and cultural knowledge, with skaldic poetry playing a central role in commemorating events and figures. Skalds, professional poets attached to royal courts, composed complex, alliterative verses that praised rulers' deeds, battles, and voyages, ensuring these narratives endured through memorization and recitation at feasts and assemblies.[12] Genealogical recitations complemented this by tracing family lineages and alliances, reinforcing social structures and historical continuity in a society without widespread writing.[13] These practices not only documented Viking Age history but also embedded moral and heroic ideals, forming the narrative backbone for later sagas. Key figures such as the lawspeakers, or lögsögumenn, were instrumental in maintaining oral lore, particularly in Iceland where the Althing assembly convened annually from around 930 CE. Elected for three-year terms, lawspeakers memorized and recited one-third of the legal code each summer at the Althing, blending juridical rules with historical precedents and genealogical details to guide disputes and foster communal memory.[14] This recitation tradition extended beyond law to include sagas of settlement and chieftains, performed before gathered free men to legitimize claims and preserve collective identity in the absence of written records.[15] Pagan mythology and heroic lays profoundly shaped the thematic content of these oral narratives, drawing from tales of gods like Odin and Thor, as well as legendary exploits transmitted through family lore during long winter evenings. Storytelling often occurred seasonally, with extended sessions in communal halls during the dark months, where elders and skalds recounted myths of creation, Ragnarök, and mortal heroes to entertain, educate, and invoke ancestral spirits.[16] These lays emphasized fate, honor, and supernatural intervention, influencing saga motifs of vengeance and kinship while being passed down generationally within households.[17] Archaeological evidence from runestones further illustrates this oral commemorative culture, as inscriptions from the 9th to 11th centuries narrate personal achievements, deaths in raids, and familial bonds, serving as public memorials that likely prompted fuller oral retellings at gatherings. Over 3,000 such stones, primarily in Sweden and Denmark, used runes to encapsulate stories of voyages to England or inheritance disputes, bridging ephemeral speech with durable markers of memory.[18] This practice hints at the gradual transition toward written forms in the 13th century, as Christian literacy began to codify these enduring oral foundations.[19]Emergence of Written Sagas in the 13th Century

The introduction of Christianity to Iceland around the year 1000 marked a pivotal shift toward literacy, as the religion's adoption at the Althing assembly facilitated the arrival of the Latin script through missionary efforts. King Óláfr Tryggvason of Norway played a central role by dispatching missionaries such as Þangbrandr in 998 or 999, whose activities culminated in the legal acceptance of Christianity in 1000, mediated by figures like Þorgeirr Ljósvetningagoði. This process also incorporated Celtic influences, including early Christian settlers known as the papar (Irish monks), and bishops like Friðrekr, who had introduced elements of the faith as early as 981. The Latin script, adapted for Old Norse with modifications to accommodate sounds like þ and ð, enabled the production of vellum codices, transitioning Iceland from an exclusively oral culture to one capable of written records.[20][20][20][21] Written sagas flourished in the 13th century amid the Sturlung Age, a period of intense civil strife from roughly 1220 to 1262 that saw the erosion of Iceland's independent commonwealth and its eventual submission to Norwegian authority. This era of feuds among chieftains and powerful families prompted the documentation of historical events, lineages, and conflicts to preserve social memory and assert claims to status and land. The breakdown of traditional governance structures during this time encouraged reflection on earlier periods, leading to the transcription of narratives that captured intergenerational disputes and heroic ancestries.[22][23][22] Manuscript production centered on the bishoprics of Skálholt in the south and Hólar in the north, which served as primary hubs for scribal activity due to their ecclesiastical resources and learned communities. These institutions, established in the 11th and 12th centuries, supported the copying and composition of texts on vellum, fostering a literate elite amid the island's isolation. The bulk of sagas were composed between 1200 and 1400 by anonymous authors who drew upon oral traditions for their source material, blending them into cohesive written prose.[24][15][25]Motivations for Saga Composition

The composition of written sagas in 13th-century Iceland served as a vital mechanism for preserving family honor and asserting legal claims, particularly during the Commonwealth period (930–1262) and the subsequent era of Norwegian subjugation following the Gamli sáttmáli treaty of 1262–1264. These narratives meticulously documented genealogies, land settlements, and disputes, tracing lineages back to the initial settlers to reinforce inheritance rights and social status amid consolidating power structures and external pressures. For instance, over three-quarters of the Sagas of Icelanders include genealogical introductions linking protagonists to the settlement generation or earlier Norwegian forebears, thereby safeguarding familial legacies against erosion under Norwegian rule.[26] This archival function was especially pronounced in the post-1262 context, where sagas helped Icelandic elites maintain autonomy in identity and property claims despite political subordination.[27] Sagas also fulfilled an educational role, imparting lessons in morality, history, and Christian values, with saints' and bishops' narratives particularly emphasizing ethical conduct and spiritual guidance. These works adapted hagiographic traditions to local contexts, portraying Icelandic bishops as exemplars of piety and restraint, thereby promoting Christian doctrines of forgiveness, humility, and communal harmony over pagan vengeance. Such narratives, drawn from translated Latin vitae and indigenous biographies like those in Byskupa sögur, instructed readers in navigating moral dilemmas, reflecting the Church's influence in shaping societal norms during Iceland's Christianization and beyond. By embedding historical events with didactic intent, sagas reinforced a shared cultural memory that valued resolution through law and faith.[28] Patronage by chieftains, or goðar, further drove saga composition as a means to legitimize their authority and consolidate influence during the turbulent Sturlung Age (c. 1220–1264). Powerful figures sponsored compilations like Sturlunga saga to highlight ancestral achievements and portray themselves as stabilizing mediators, thereby justifying concentrated power in an era of feuds and Norwegian encroachment. The elite's commissioning of these texts, often under the supervision of figures like Magnús Þórðarson, underscored their role in crafting narratives that aligned local leadership with emerging monarchical ideals for peace and order.[27]Classification and Genres

Kings' Sagas

The Kings' Sagas, known in Old Norse as konungasögur, constitute a genre of Old Norse-Icelandic literature comprising biographical and historical narratives centered on the lives and reigns of Norwegian and Danish monarchs from the 9th to the 13th centuries. These works emerged in the 12th century as part of a broader effort to document Scandinavian royal history in the vernacular, distinct from Latin chronicles. The earliest known precursor is Ari Þorgilsson's Íslendingabók (c. 1120–1133), a concise history of Iceland that includes brief accounts of Norwegian kings to contextualize the island's settlement and Christianization, marking the initial Icelandic engagement with royal biography.[29][30] The genre reached its zenith in the 13th century through major compilations and individual sagas. Key compilations include Morkinskinna (c. 1220), a collection spanning from the 11th to early 13th centuries with a focus on Norwegian kings and their interactions with Icelanders; Fagrskinna (c. 1225), a more selective history emphasizing exemplary rulers; and Heimskringla (c. 1230), attributed to Snorri Sturluson, which provides a comprehensive chronicle from mythical origins to 1177. Separate sagas, such as Óláfs saga helga (c. 13th century), offer standalone biographies, in this case detailing the life of King Óláfr Haraldsson (St. Óláfr), Norway's patron saint, and his role in Christianization. These texts were composed primarily in Iceland but drew on oral traditions, skaldic poetry, and continental sources to construct royal lineages.[29][30] Structurally, the Kings' Sagas are organized as chronological narratives that blend euhemerized myths—treating pagan gods as historical kings—with documented events up to the 12th century, often incorporating skaldic verses as eyewitness testimony to authenticate accounts. Compilations like Heimskringla cover expansive periods of 150 to 300 years, linking legendary forebears (e.g., the Ynglings) to contemporary rulers through successive biographies, while separate sagas focus on individual reigns with hagiographic elements for saintly figures. This prosimetric form—alternating prose and poetry—lends a rhythmic, mnemonic quality reflective of oral precursors.[30][29] The primary purposes of these sagas were to legitimize the Norwegian monarchy by tracing its antiquity and divine favor, while embedding narratives of Christian conversion to underscore the transition from paganism to Christianity under kings like Óláfr Tryggvason and Óláfr helgi. Composed amid Iceland's political ties to Norway, they served ideological functions, promoting royal authority and national identity in the medieval North, as evident in their polyphonic portrayal of power dynamics and moral exemplars.[30][29]Sagas of Icelanders

The Sagas of Icelanders, or Íslendingasögur, constitute a distinctive genre of Old Norse prose literature that chronicles the lives, conflicts, and daily realities of Icelandic settlers and their descendants during the island's formative Commonwealth period. These narratives center on events spanning roughly 930 to 1030 CE, a time marked by the establishment of social structures among chieftains (goðar), farmers, and freeholders in a harsh, isolated environment. Unlike more fantastical or royal-focused tales, the Íslendingasögur emphasize local individualism, family lineages, and interpersonal dynamics, blending historical plausibility with dramatic storytelling to evoke medieval Icelandic society.[22] Key characteristics include an objective third-person narration delivered in a sparse, succinct style that prioritizes action over psychological depth or descriptive flourishes, often integrating brief skaldic verses to lend authenticity to reported events. The tone remains neutral and non-moralizing, allowing readers to infer values from deeds rather than authorial judgment, while complex plots weave multiple feuds and alliances into a cohesive whole. Honor emerges as a core driver, fueling cycles of revenge that test personal and communal bonds, frequently resolved—or escalated—through legal proceedings at assemblies like the Althing, Iceland's national gathering for lawmaking and dispute settlement.[31][22][32] Recurring themes highlight the tensions of Iceland's pagan-to-Christian transition around 1000 CE, portraying shifts in belief systems amid ongoing pagan practices and the integration of Christian ethics into social norms. Communal assemblies serve not only as venues for justice but also as microcosms of societal negotiation, underscoring the importance of consensus in a leaderless republic. Rooted in oral family traditions passed down through generations, these sagas were primarily composed in written form during the 13th century.[33][32][31] Among the approximately 40 major Íslendingasögur,[1] standout examples are Egils saga, which follows the turbulent life of the warrior-poet Egill Skallagrímsson across generations of strife; Laxdæla saga, delving into romantic rivalries and inheritance disputes in the western fjords; and Njáls saga (c. 1270–1300), a pinnacle of the genre for its intricate depiction of prophetic visions, burnings, and the era's religious upheavals. These works, along with numerous shorter þættir (anecdotal tales), total around 100 narratives, preserving a vivid record of Iceland's early cultural identity.[22][31]Contemporary Sagas

Contemporary sagas, also known as samtíðarsögur, are a genre of Icelandic prose literature that documents historical events and figures from the 12th and 13th centuries, composed shortly after the occurrences they describe.[34] Unlike the more fictionalized Sagas of Icelanders, which evoke a timeless past, contemporary sagas adopt a journalistic approach, emphasizing factual reporting of recent history with a focus on political and social dynamics in Iceland.[34] They provide detailed accounts of the turbulent period leading to the end of Iceland's independence, particularly the civil conflicts that facilitated Norwegian influence.[35] The central text in this genre is the Sturlunga saga, a compilation assembled around 1270–1280, with later redactions such as the Króksfjarðarbók (ca. 1350–1370) and Reykjarfjarðarbók (ca. 1375–1400).[34][35] This collection encompasses nine principal sagas, including Íslendinga saga by Sturla Þórðarson and Sturlu saga, along with shorter þættir, spanning events from 1117 to 1284 but centering on the Age of the Sturlungs (ca. 1220–1264).[35] The narrative chronicles the consolidation of power among a few chieftain families, escalating feuds, and the eventual submission of Iceland to Norwegian rule through the Gamli sáttmáli treaty of 1262, marking the end of the commonwealth.[35] Key episodes include the Battle of Örlygsstaðir in 1238, where Snorri Sturluson's forces clashed with those of Gizurr Þorvaldsson, and the Battle of Haugsnes on April 19, 1246, which further weakened local autonomy.[35] The style of contemporary sagas is marked by a realistic, chronicle-like precision, incorporating eyewitness testimonies, specific dates, and verbatim speeches to convey political intrigue and decision-making processes.[35] For instance, Íslendinga saga includes direct dialogues, such as Gizurr Þorvaldsson's truce negotiations and Sturla Þórðarson's defense during his 1263 journey to Norway, highlighting the diplomatic maneuvers amid factional rivalries.[35] This contrasts with the impersonal, timeless quality of earlier saga genres by grounding events in verifiable chronology and personal observations, often drawn from the authors' or informants' direct experiences.[34][36] Supernatural elements are minimal, appearing only sporadically—such as implied divine protection in Aron Hjörleifsson's escapes or rare miracles in Hrafns saga Sveinbjarnarsonar—to underscore moral or ecclesiastical themes rather than drive the plot.[35] Central to the narratives are the power struggles among influential chieftains, exemplified by Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241), a lawspeaker, poet, and mediator whose diplomatic efforts in Norway (1218–1220 and 1233) intertwined with local feuds, culminating in his assassination amid suspicions of disloyalty to King Hákon IV.[35] Another key figure is Guðmundr Arason (1161–1237), Bishop of Hólar, whose tenure involved ecclesiastical disputes and mediation in secular conflicts, portraying the Church's expanding role in politics; his death and subsequent cult, including relic veneration, reflect tensions between spiritual authority and temporal power.[35] These accounts emphasize mechanisms like arbitration by clerics, such as Abbot Brandr Jónsson, to navigate the concentration of chieftaincies and the erosion of communal governance during the era's violence.[35] Overall, contemporary sagas serve as a historical record of Iceland's transition from independence to Norwegian dominion, preserving cultural memory through terse, insightful depictions of societal upheaval.[36][35]Legendary Sagas

Legendary sagas, known in Old Norse as fornaldarsögur, constitute a genre of medieval Icelandic prose narratives set in the distant past of Scandinavia, prior to the settlement of Iceland around 870 CE, blending historical reminiscences with mythological elements drawn from continental legends adapted into a Norse context.[37] These works often incorporate supernatural occurrences, such as divine interventions and monstrous adversaries, distinguishing them from the more verisimilar accounts in sagas of Icelanders that emphasize realistic human conflicts.[37] The primary collection preserving these texts is Fornaldarsögur Norðurlanda (Sagas of Ancient Times of the Northern Lands), a four-volume compilation edited in the late 19th century by Valdimar Ásmundarson, which draws from medieval manuscripts to assemble over two dozen individual sagas.[38] A prominent example within this corpus is Völsunga saga, composed around the 13th century, which recounts the exploits of the Völsung clan, including the hero Sigurd's slaying of the dragon Fafnir to claim a cursed treasure.[39] This saga exemplifies the genre's characteristic features, such as heroic quests across mythical landscapes, encounters with giants and otherworldly beings, and the recurring motif of accursed gold that brings doom to its possessors, often interwoven with verses from eddic poems like Atlakviða, which depicts the tragic fate of Sigurd's kin at the hands of the Hunnish king Atli.[37] These elements reflect influences from oral mythological traditions that predate the written form, preserving echoes of pre-Christian beliefs in a prose framework.[38] Composed primarily between 1300 and 1500, the legendary sagas served dual purposes: providing entertainment through thrilling tales of adventure and valor, and safeguarding fragments of ancient Norse lore amid the Christianization of Iceland. Their inclusion of fantastical events—trolls, shape-shifters, and prophetic dreams—sets them apart from purely historical sagas, which adhere more closely to documented events and genealogies without overt supernaturalism.[37]Chivalric Sagas

Chivalric sagas, known as riddarasögur, originated in the 13th century as translations and adaptations of Old French romances into Old Norse, commissioned by Norwegian King Hákon Hákonarson to cultivate continental courtly ideals in Scandinavia.[40] The earliest surviving example, Tristrams saga ok Ísöndar, dates to around 1226 and represents an abridged rendering of the Anglo-Norman poet Thomas of Britain's Tristan, emphasizing tragic love and adventure.[40] This royal initiative, part of broader efforts to align Norse culture with European chivalry, marked the introduction of romance literature to the North, with subsequent translations including Arthurian tales and lais.[41] These sagas typically feature motifs of courtly love, knightly quests, tournaments, and enchanted artifacts, set against backdrops of distant realms like Britain or Byzantium to evoke an aura of exotic grandeur and moral testing.[42] Unlike the more historically grounded sagas of Icelanders, riddarasögur prioritize emotional introspection, gender dynamics, and heroic ideals drawn from French sources, often blending them with Norse stoicism.[41] The genre divides into translated works, such as Ívens saga—a close adaptation of Chrétien de Troyes' Yvain, ou le chevalier au lion—and indigenous compositions crafted in Iceland, which innovate on romance structures with local motifs like bridal quests or hybrid monsters while retaining core chivalric elements.[43] Production of riddarasögur peaked in the 14th century but declined by 1400 as Icelandic audiences favored more vernacular and fantastical narratives, though the genre's legacy endured in the form of rímur, rhymed ballads that versified chivalric themes for oral performance.[42]Saints' and Bishops' Sagas

Saints' and Bishops' Sagas constitute a distinct genre within Old Norse-Icelandic literature, encompassing vernacular hagiographies known as heilagra manna sögur that narrate the lives of Christian saints and, particularly, Icelandic bishops. These works integrate biographical details with accounts of miracles, sermons, and church governance, functioning as tools for religious instruction and the promotion of sanctity in a newly Christianized society. Composed primarily from the late 12th to the 14th century, they reflect the adaptation of continental hagiographical models to local ecclesiastical narratives, emphasizing the holiness of native figures to foster devotion among Icelandic audiences.[44] Key examples include Jóns saga helga, which chronicles the life of Bishop Jón Ögmundsson (d. 1121), the inaugural bishop of the Hólar diocese from 1106, composed around 1200 in the wake of his canonization by Pope Innocent III in 1201. Likewise, Þorláks saga portrays Bishop Þorlákur Þórhallsson (d. 1193), who served Skálholt from 1178, with the saga emerging shortly after his local canonization in 1198. These texts feature miracle stories—such as healings, prophetic visions, and divine interventions—alongside depictions of ecclesiastical conflicts, drawing stylistic influences from Latin vitae, including those of martyrs like Thomas Becket, to blend edification with dramatic narrative.[44][45] The sagas' inclusion of sermons and political intrigue underscores their role in advancing church agendas, portraying bishops as intercessors who navigated tensions between secular chieftains and ecclesiastical authority. In 13th- and 14th-century Iceland, they actively supported the cult worship of local saints, providing narratives that legitimized ongoing veneration and bolstered the institutional power of the church amid the Sturlung Age's upheavals. For instance, Jóns saga helga highlights Jón's humility and pastoral zeal to inspire clerical reform, while Þorláks saga integrates episodes like the Oddaverja þáttr to illustrate struggles over church property rights.[44][45] Broader collections, such as the Biskupa sögur (Bishops' Sagas), compile these works and extend to Scandinavian contexts, including the lives of Norwegian bishops like those in Passio et miracula sancti Olavi. These compilations, edited in the 19th and 20th centuries from medieval manuscripts, underscore the genre's emphasis on Nordic ecclesiastical history and the shared Christian heritage across the region.[46]Manuscripts and Transmission

Major Icelandic Manuscripts

The major Icelandic manuscripts preserving sagas are primarily codices written on vellum during the medieval period, produced by skilled scribes—often priests or educated laymen—using calfskin prepared through a labor-intensive process of scraping, liming, and stretching to create durable pages suitable for long-term preservation. These manuscripts were typically bound between wooden boards for protection and sometimes featured illuminated initials or simple decorations to enhance readability and aesthetic appeal, reflecting the cultural and religious contexts of their creation on monastic estates or rural farms in Iceland. Ownership often shifted between ecclesiastical institutions, wealthy families, and later collectors, contributing to their transmission across centuries.[47] Among the most significant surviving examples is the Codex Regius (GKS 2365 4to), a late 13th-century vellum manuscript of approximately 45 leaves that preserves the Poetic Edda—a collection of mythological and heroic lays central to Norse literature—and includes poetic material foundational to the Völsunga saga, such as narratives of Sigurd and the Niflungar. This compact codex, measuring about 194 by 133 mm, was likely produced in southern Iceland and represents a pinnacle of anonymous scribal artistry, with its unadorned but precise script ensuring the fidelity of oral traditions in written form; it was acquired by the Danish scholar Árni Magnússon in the early 18th century and returned to Iceland in 1971, underscoring its enduring historical value as a key artifact of medieval Icelandic heritage.[48] The Flateyjarbók (GKS 1005 fol.), compiled between 1387 and 1394 by the priests Jón Þórðarson and Magnús Þorhallsson for the chieftain Jón Hákonarson, stands as the largest and most elaborately decorated medieval Icelandic manuscript, comprising 225 vellum leaves (originally 202, with additions) filled with kings' sagas, including extensive accounts of Norwegian rulers from Harald Fairhair to the 14th century, alongside shorter works like the Grœnlendinga saga and rímur poetry. Spanning about 585 by 415 mm when open, it features vibrant illuminated initials and marginal illustrations that highlight its status as a bespoke luxury item, produced at the farm Víðidalstunga in northern Iceland; its compilation reflects the era's interest in compiling historical narratives for elite patrons, and despite partial disassembly in the 17th century, it remains a cornerstone for studying saga transmission, now housed jointly in Iceland and Denmark.[47][49] Another pivotal codex is the Möðruvallabók (AM 132 fol.), dating to circa 1330–1370 and inscribed on 200 vellum leaves bound in wooden boards, which assembles the most comprehensive collection of Sagas of Icelanders in a single volume, containing 11 complete narratives such as Njáls saga, Egils saga Skallagrímssonar, and Laxdœla saga. Measuring roughly 340 by 240 mm, this mid-14th-century manuscript from northern or western Iceland exemplifies the consolidation of family sagas into thematic compilations, likely for scholarly or communal use on a farm like Möðruvellir; its survival intact highlights the resilience of such works, and it serves as a primary source for textual criticism due to its early and reliable variants.[47] Of the estimated 700–1,000 medieval vellum manuscripts produced in Iceland—predominantly between the 13th and 15th centuries—approximately 800 complete codices and fragments remain extant today, with the majority preserved in institutions like the Árni Magnússon Institute in Reykjavík, the Royal Library in Copenhagen, and the National Library of Sweden, reflecting Iceland's unique literary output relative to its small population. Tragically, many others were lost to environmental disasters, including the Great Fire of Copenhagen in 1728, which destroyed around one-third of the city's structures and consumed numerous Icelandic manuscripts from Árni Magnússon's collection despite his heroic efforts to salvage them by throwing volumes from windows; this event nonetheless spared most vellum codices, allowing their repatriation to Iceland between 1971 and 1997 as symbols of national identity.[50][47]Editing and Translation Efforts

The Icelandic Literary Society (Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag), founded in 1816, initiated a major project to edit and publish Old Norse texts, including sagas, with an emphasis on normalized versions to make them accessible for scholarly study.[51] Among its early efforts was the two-volume edition of Sturlunga saga in 1817–1820, marking the beginning of systematic 19th-century saga publications that prioritized diplomatic transcriptions alongside normalized texts.[51] This initiative continued through the century, producing editions that standardized orthography while preserving manuscript variants, laying the groundwork for later comprehensive series like Íslenzk fornrit, which began in 1933 but built on these foundations.[51] Prominent 19th-century scholars Guðbrandur Vigfússon and Eiríkr Magnússon advanced translation efforts through their contributions to the Rolls Series (Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores), a British project publishing medieval chronicles.[52] Vigfússon edited volumes such as Icelandic Sagas and Other Historical Documents Relating to the Settlements and Descents of the Northmen on the British Isles (1887–1894, Rolls Series 88), providing facing-page Old Norse texts and English translations of sagas like Orkneyinga saga and Hákonar saga.[52] Magnússon, often collaborating or competing with Vigfússon, translated saints' lives and bishops' sagas, including Thomas saga erkibyskups (1875–1883, Rolls Series 65), emphasizing literal renderings to convey the original's stylistic restraint.[53] These works, spanning the 1860s to 1880s, introduced sagas to English-speaking audiences and highlighted philological rigor in handling archaic language.[52] In the 20th century, editing efforts expanded with specialized collections, such as the four-volume Fornaldar sögur Norðurlanda (1943–1954), edited by Guðni Jónsson, which compiled legendary sagas like Völsunga saga and Hrólfs saga kraka in normalized Old Norse, drawing from multiple manuscripts to resolve textual discrepancies.[54] This edition became a standard reference for fornaldarsögur, prioritizing completeness over exhaustive variant collation.[54] The 21st century has seen a shift to digital initiatives, exemplified by the Medieval Nordic Text Archive (Menota), an ongoing project launched in 2003 that encodes sagas and other medieval texts in XML/TEI format for searchable, diplomatic editions.[55] Menota addresses preservation by digitizing facsimiles and transcriptions, enabling global access while maintaining fidelity to original paleography.[55] Editing sagas presents persistent challenges, including reconciling variant readings across manuscripts, filling or noting lacunae from damaged folios, and standardizing spelling without altering semantic nuances.[56] For instance, editors must navigate orthographic inconsistencies in 13th–14th-century codices, where normalized modern Icelandic spelling risks smoothing dialectal features evident in originals.[56] These issues require rigorous stemmatic analysis to reconstruct plausible archetypes, as seen in treatments of fragmentary texts like parts of Heiðreks saga.[57]Modern Interpretations and Influence

Scholarly Analysis

In the nineteenth century, romantic nationalism in Iceland and Scandinavia portrayed the sagas as authentic historical records, serving to bolster national identity during periods of foreign domination, particularly under Danish rule. This perspective emphasized the sagas' role in constructing a heroic past, with scholars like Jón Sigurðsson viewing them as reliable chronicles of medieval events to support independence movements.[8] However, by the 1920s, Sigurður Nordal shifted scholarly focus toward literary analysis, arguing that sagas such as Hrafnkels saga exemplified fictional artistry and individual authorial creativity rather than verbatim history. In works like Snorri Sturluson (1920), Nordal highlighted the rationalist and secular elements of saga composition, portraying them as sophisticated prose narratives akin to novels.[58] A central debate in saga studies concerns the "book-prose" and "free-prose" theories, which address whether sagas originated from oral traditions or were invented as written literature. Proponents of the free-prose theory, including Sigurður Nordal, contended that sagas were original literary creations by thirteenth-century authors, drawing on historical knowledge but prioritizing artistic invention over oral fidelity.[59] In contrast, book-prose advocates like Knut Liestøl argued that sagas evolved from pre-existing oral narratives, with written versions preserving core historical elements through adaptation.[59] This dichotomy, peaking in the early twentieth century, continues to influence discussions on authorship and historicity, though contemporary views often integrate elements of both.[59] Feminist scholarship has illuminated women's agency in sagas, particularly in Njáls saga, where female characters like Hallgerðr and Bergþóra transgress gender norms to drive conflict and vengeance. Hallgerðr's refusal to aid Gunnarr and her incitement of theft exemplify how women wield indirect power, challenging passive ideals and invoking pagan honor codes amid Christian transitions.[60] Postcolonial readings further explore sagas' role in shaping Icelandic identity, viewing them as sites of resistance against colonial narratives, as seen in analyses of Hrafnkels saga Freysgoða where landscapes and power dynamics reflect decolonization and cultural repatriation.[61] These interpretations frame sagas as palimpsests of national self-assertion, linking medieval texts to modern postcolonial landscapes.[61] Recent digital humanities approaches employ stylometric analysis to probe saga authorship and redactions, as in studies of Ljósvetninga saga, where frequency-based metrics reveal stylistic consistencies between parallel and divergent sections, supporting revised textual histories over oral origins.[62] Corpus linguistics complements this through resources like the Saga Corpus, a 1.5-million-word collection of normalized Old Norse texts including family sagas, enabling morphosyntactic tagging and language evolution studies with high accuracy (up to 93.5%).[63] Such methods quantify linguistic patterns, enhancing debates on genre and transmission without exhaustive listings of metrics.[63]Representations in Popular Culture

The Icelandic sagas have profoundly influenced modern literature, particularly through their heroic motifs and epic narratives. Richard Wagner's operatic cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), commonly known as the Ring cycle, drew central inspiration from the Völsunga saga, incorporating elements such as the cursed ring, dragon-slaying hero Sigurd, and familial betrayals to explore themes of fate and power.[64] Similarly, J.R.R. Tolkien's fantasy works, including The Lord of the Rings, were shaped by the structure, language, and heroic archetypes found in the Icelandic sagas, which Tolkien studied extensively as a philologist; he incorporated motifs like shape-shifting, warrior quests, and ancient lineages, viewing the sagas as vital to understanding medieval Northern European literature.[65][66] In film and television, the sagas' tales of feuds, exploration, and Norse heroism have been adapted to dramatize Viking life. The History Channel series Vikings (2013–2020), created by Michael Hirst, incorporates elements from the sagas of Ragnar Lothbrok, blending historical lore with fictionalized accounts of raids, family rivalries, and pagan rituals to portray the transition from mythology to Christianity.[67] Its Netflix spin-off Vikings: Valhalla (2022–2024) continues this tradition, drawing on kings' sagas and Vinland sagas to depict figures like Leif Erikson, Freydís Eiríksdóttir, and Harald Hardrada in stories of exploration, vengeance, and Christianization. The 1981 Icelandic film Outlaw: The Saga of Gisli (original title Útlaginn), directed by Ágúst Guðmundsson, directly adapts Gísla saga Súrssonar, focusing on the protagonist's outlawry amid a blood feud in 10th-century Iceland, emphasizing themes of honor, vengeance, and isolation in a stark, realistic style faithful to the saga's tone.[68] The sagas' influence extends to music and video games, where their mythic and martial elements fuel creative reinterpretations. Viking metal band Amon Amarth frequently references Icelandic sagas in their lyrics and concept albums; frontman Johan Hegg has cited Egils saga Skallagrímssonar as a key inspiration, drawing on its portrayal of the poet-warrior Egill's pagan defiance and battles to craft songs about Norse resilience and fate.[69][70] In gaming, God of War (2018), developed by Santa Monica Studio, blends saga narratives with Norse mythology, reimagining Kratos in Midgard through quests echoing heroic journeys like those in the Völsunga saga, such as father-son bonds and realm traversals, while adapting motifs of gods, giants, and cursed artifacts for interactive storytelling. Its sequel, God of War Ragnarök (2022), further incorporates saga elements in its apocalyptic narrative and character arcs.[71] In the 21st century, renewed interest in the sagas has led to innovative formats like graphic novels and podcasts, enhancing their accessibility and cultural reach. Adaptations such as Northlanders: The Icelandic Saga (2009–2010) by Brian Wood and various artists reimagine 11th-century Icelandic conflicts through serialized comics, capturing the sagas' gritty realism and clan dynamics in visual form.[72] Similarly, the Eyrbyggja saga graphic novel (2022) illustrates the intertwined lives of early Icelandic settlers, blending historical drama with illustrative panels to evoke the original text's supernatural and feuding elements.[73] Podcasts like Saga Thing (2013–present), hosted by Karl Seigfried and John Maudr, dissect sagas such as Egils saga episode by episode, combining scholarly discussion with humor to engage modern audiences.[74] These revivals have also spurred tourism in Iceland, with saga-themed tours to sites like Þingvellir and Snæfellsnes drawing visitors to trace literary landscapes, as promoted by cultural institutions to highlight the nation's heritage.[75][76] Upcoming projects include the drama series Fury (in development, announced October 2025), inspired by the Sturlunga saga and focusing on 13th-century Icelandic civil strife.[77]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/sek%25CA%25B7-