Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gothic double

View on Wikipedia| Gothic double motif | |

|---|---|

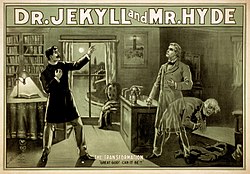

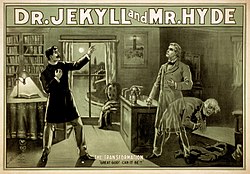

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is one of the most famous examples of the Gothic double motif in literature. | |

| Stylistic origins | Gothic fiction, Romanticism, Horror |

| Cultural origins | Originated in Celtic folklore through lookalike figures such as the fetch, and in late 18th-century German literature |

| Popularity | Consistently popular in literature from 18th century to 21st century, present in famous texts such as The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde |

| Formats | Present in a wide variety of formats including novels, films, short stories, and plays |

| Authors | Johann Paul Richter, Mary Shelley, Charlotte Bronte, Emily Bronte, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Edgar Allan Poe, Robert Louis Stevenson, Daphne du Maurier, Jeff VanderMeer |

| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History | ||||||

| Lists and outlines | ||||||

| Theory and criticism | ||||||

|

| ||||||

The Gothic double is a literary motif which refers to the divided personality of a character. Closely linked to the Doppelgänger, which first appeared in the 1796 novel Siebenkäs by Johann Paul Richter, the double figure emerged in Gothic literature in the late 18th century due to a resurgence of interest in mythology and folklore which explored notions of duality, such as the fetch in Irish folklore which is a double figure of a family member, often signifying an impending death.[1]

A major shift in Gothic literature occurred in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, where evil was no longer within a physical location such as a haunted castle, but expanded to inhabit the mind of characters, often referred to as "the haunted individual."[2] Examples of the Gothic double motif in 19th-century texts include Charlotte Brontë's novel Jane Eyre (1847) and Charlotte Perkins Gilman's short story The Yellow Wallpaper (1892), which use the motif to reflect on gender inequalites in the Victorian era,[3] and famously, Robert Louis Stevenson's novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886).

In the early 20th century, the Gothic double motif was featured in new mediums such as film to explore the emerging fear of technology replacing humanity.[4] A notable example of this is the evil mechanical double depicted in the German expressionist film Metropolis by Fritz Lang (1927). Texts in this period also appropriate the Gothic double motif present in earlier literature, such as Daphne du Maurier's Gothic romance novel Rebecca (1938), which appropriates the doubling in Jane Eyre.[5] In the 21st century, the Gothic double motif has further been featured in horror and psychological thriller films such as Darren Aronofsky's Black Swan (2010) and Jordan Peele's Us (2019).[1] In addition, the Gothic double motif has been used in 21st century Anthropocene literature, such as Jeff VanderMeer's Annihilation (2014).

Origins

[edit]

The emergence of the Gothic novel in the 18th century coincided with a renewed interest in Celtic folklore and pagan mythology, which is abundant with supernatural double figures.[6][7] The period from 1750 to 1830 is known as the “Gothic and Celtic revival”[8] in which the Irish, Scottish, and Welsh folklore which had previously become absorbed into British literature as a result of colonial expansion into these territories began to influence the development of the Gothic genre.[8] For example, the doppelgänger motif was inspired by the Celtic double figure called the fetch[9] or Macasamhail,[10] a lookalike of a relative or friend who would appear as an omen of death if encountered at night, according to Irish and Scottish superstition.[11]

Short stories detailing encounters with fetches began to appear in the early 19th century,[6] such as the tale The Fetches (1825) published by Irish brothers John Banim and Michael Banim, and the collection of ghost-sightings The Night Side of Nature (1848) published by Catherine Crowe.[6] Crowe's collection of tales featured a chapter detailing encounters with double figures, including John Donne's claim that he saw a double of his wife holding a dead child in Paris at the same moment she gave birth to their stillborn child in London.[6] In these early Gothic tales, the double was believed to be a sentient spirit which had the ability to leave the physical body and travel to communicate with family members.[6]

18th century

[edit]Siebenkas (1796)

[edit]The German Romantic novel Siebenkas features the first appearance of the term doppelgänger, meaning double-walker.[6][12] A footnote in the novel which first coins the term defines doppelgänger as “the name for people who see themselves.”[6][13] Unlike the supernatural fetch in Celtic folklore, in Siebenkas the doppelgänger is initially not a supernatural apparition or hallucination but Siebankas’ friend Leibgeber who looks very similar to Siebenkas except for his limp.[12] However, later in the novel the term doppelgänger begins to take on the meaning of a hallucination when Leibgeber is represented as Siebenkas’ alter ego or spectre rather than just his lookalike friend.[12] This novel marked the beginning of the Gothic double motif as a sinister split personality.[12]

19th century

[edit]Victorian Gothic literature altered depictions of evil to explore the potential darkness of the human mind. Rather than evil being an external force such as a ghost haunting a castle, as apparent in early Gothic texts such as Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764), Victorian Gothic literature examined how evil can exist within the minds of individuals.[14] As a result, the double motif was heavily featured in Victorian Horror to explore the innate darkness of humanity rather than just the presence of external sources of evil.[14] Manifestations of the double motif in this period include mirrors, shadows, reflections, and automatons.[14]

Novels

[edit]Jane Eyre (1847)

[edit]

Charlotte Brontë's novel Jane Eyre uses the Gothic double motif to mirror the protagonist Jane Eyre with Mr Rochester's wife Bertha Mason[15][16] who is imprisoned in the attic of Thornfield Hall due to an unidentified mental illness. This doubling between the identities of Jane and Bertha is used to challenge the expected roles of women regarding marriage and sexuality in the Victorian era.[3] In the novel, Bronte alters the typical use of the double figure by placing the motif into a domestic rather than supernatural context which addresses marriage issues, as Jane is the second wife of Mr Rochester who replaces his first wife, Bertha Mason.[3][16] While Jane is initially represented as Bertha's replacement and therefore her opposite, their identities are doubled in the novel to represent the powerlessness of women during this era,[3] as both characters are imprisoned within gender stereotypes imposed on them by Mr Rochester. Bertha symbolises Jane's repressed desires for freedom and independence in a context which restricts women's lives through marriage,[15] as evident in the chapter describing the night before Jane's wedding where Bertha appears in her bedroom and rips her wedding veil,[15] as shown in the quote below.

“But presently she took my veil from its place; she held it up, gazed at it long, and then she threw it over her own head, and turned to the mirror. At that moment I saw the reflection of the visage and features quite distinctly in the dark oblong glass…Sir, it removed my veil from its gaunt head, rent it in two parts, and flinging both on the floor, trampled on them.” [17]

This quote uses the mirror motif commonly featured in 19th century Gothic literature[2] to enhance the doubling of Jane and Bertha's identities. Through staring at herself in the mirror while wearing Jane's wedding veil and ripping the veil in half, Bertha embodies Jane's repressed anger and her desire to escape the confines of marriage.[15][16] Jane's longing for independence is finally enacted by Bertha at the end of the novel when she burns down Thornfield Hall, which symbolises a destruction of Mr Rochester's dominance over her identity.[15]

Short stories

[edit]The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886)

[edit]

Robert Louis Stevenson's novella The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a famous example of the Gothic double motif which explores the duality of man and the inner struggle between good and evil within the mind of an individual.[18] In the novella, the physician Dr Henry Jekyll invents a medicine which allows one to separate their good and bad selves from each other, transforming into the evil and grotesque Mr Hyde when he takes the drug.[19][20][21] Notably, Dr Jekyll's transformation into his evil double is not supernatural, but rather facilitated by a scientific experiment, reflecting the growing interest in science and psychology in the 19th century.[22] However, much like the monstrous creation in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, this ambition of scientific discovery and advancement has disastrous consequences for Dr Jekyll as he is consumed by the evil within him.[23] Stevenson's novella suggests that the desire to solve mysteries of the human condition through science are impossible, as Dr Jekyll is unable to control the evil aspect of his identity and his experiment ultimately fails.[24]

The novella also comments on the awareness of drug addiction which emerged in the late 19th century,[25][26] which was viewed as a mental and moral deficiency linked to the pursuit of vice. Mr Hyde is represented in the novella as the embodiment of addiction,[27] a destructive and evil figure who unleashes chaos upon the life of Dr Jekyll, resulting in his suicide. Some interpretations argue that Mr Hyde is not a real figure but a hallucination of Dr Jekyll's, caused by his addiction to drugs and deviant behaviour which has resulted in psychological damage.[28]

The Yellow Wallpaper (1892)

[edit]

Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Gothic short story The Yellow Wallpaper utilises the double motif to explore the impact of patriarchal authority on the freedom of women. The Yellow Wallpaper is an example of the Female Gothic sub-genre[29] through its use of the double motif to expose the fragmented and divided identities that women experience as a result of societal limitations in the 19th century. Written in an epistolary structure as a series of diary entries, the story is narrated by a woman who has been confined to an isolated manor in order to recover from postpartum depression, cared for by her physician husband who frequently dismisses her illness as trivial and made-up.[30] Echoing Bertha Mason's imprisonment in the attic in Jane Eyre, the narrator of The Yellow Wallpaper is similarly confined to an upper room of the manor which features a bright yellow Arabesque patterned wallpaper that she becomes increasingly obsessed with, spending hours trying to make sense of the confusing pattern.[31] The narrator begins to experience hallucinations that the figure of a woman is creeping behind the wallpaper and shaking it as if she is trying to escape, as shown in the quotes below.

"This wallpaper has a kind of sub-pattern in a different shade, a particularly irritating one, for you can only see it in certain lights, and not clearly then. But in the places where it isn't faded and where the sun is just so – I can see a strange, provoking, formless sort of figure, that seems to skulk about behind that silly and conspicuous front design." [32] “The faint figure behind seemed to shake the pattern, just as if she wanted to get out.” [33]

The narrator's schizophrenic hallucination is a metaphor for her divided identity controlled by the authority of her husband, in which the woman behind the wallpaper symbolises her repressed self,[34] imprisoned within the patriarchal institution of marriage and motherhood.[35] At the end of the story the narrator begins to identify herself with the figure behind the wallpaper so that their identities merge and become indistinguishable from one another, confirming that the figure represents her repressed double.[36] This is shown when the narrator locks herself in the room and rips the wallpaper off the walls in an attempt to free the imprisoned woman, preparing a rope so that she can tie the woman up when she emerges from behind the wallpaper.

"I've got a rope up here that even Jennie did not find. If that woman does get out, and tries to get away, I can tie her!" [37]

This statement indicates that the narrator still views herself and the woman as separate people as she plans to tie the woman up, however, this distinction is soon blurred once she succeeds in ripping off the wallpaper.[38] The quotes below demonstrate this final merging of identities between the narrator and the woman behind the wallpaper, in which her repressed self is liberated.

"I don't like to look out of the windows even – there are so many of those creeping women, and they creep so fast. I wonder if they all come out of that wall-paper as I did? But I am securely fastened now by my well-hidden rope...I suppose I shall have to get back behind the pattern when it comes night, and that is hard!" [39] "'I've got out at last,' said I, 'in spite of you and Jane. And I've pulled off most of the paper, so you can't put me back!'" [39]

20th century

[edit]Novels

[edit]Rebecca (1938)

[edit]

Daphne du Maurier's Gothic romance novel Rebecca uses the double motif to explore the inability of women to fulfil gender expectations in the 20th century, particularly the idea of a perfect wife.[40] This is explored in the struggles of the unnamed narrator who, after impulsively marrying the aristocrat Maxim de Winter, experiences feelings of inadequacy when trying to measure up to the esteemed reputation of his deceased wife Rebecca.[40][41] As the novel progresses, the narrator becomes increasingly obsessed with the ghostly memory of Rebecca, who she views as the embodiment of an ideal wife.[40][41][42] Echoing the doubling of wives in Jane Eyre,[5] Rebecca centres on a doubling of identities between the timid and obedient second wife[43] and the rebellious first wife, Rebecca.[42] While the narrator views Rebecca as her rival, she is simultaneously her alter ego,[44] embodying the rebelliousness and freedom that the narrator is unable to obtain in her marriage to Maxim. This doubling is represented using the mirror motif, much like in Jane Eyre, as evident in the following quote where the narrator dreams that she is Rebecca.

“I got up and went to the looking glass. A face stared back at me that was not my own. It was very pale, very lovely, framed in a cloud of dark hair. The eyes narrowed and smiled. The lips parted. The face in the glass stared back at me and laughed…Maxim was brushing her hair. He held her hair in her hands, and as he brushed it he wound it slowly into a thick rope. It twisted like a snake, and he took hold of it with both hands and smiled at Rebecca and put it round his neck.” [45]

Films

[edit]Metropolis (1927)

[edit]

Silent German Expressionist film Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang, uses the motif of a mechanical double to reflect concerns about the growing influence of technology in Germany's Weimar Republic.[46][47][48] Depicting a hierarchical society dominated by technology[49] where the lower class workers live below ground and operate machinery to keep the city above ground functioning, the film exposes the dehumanisation that lower-class people are subject to, as the workers are represented as part of the machinery itself through their synchronised, rhythmic movements.[50][51][52][53] This is emphasised when the scientist Rotwang creates an evil automaton double of the character Maria, a maternal Madonna-like figure who symbolises purity, goodness, and liberation from oppressive class hierarchies.[54] The robotic double of Maria is her demonic opposite, embodying promiscuity and chaos,[55][56] as evident in the dark eyeliner she wears which distinguishes her from the purity of the real Maria, and in the scene where robot Maria performs a seductive dance at the Yoshiwara nightclub in front of a male audience who gaze at her with desire.[47][57] While Maria symbolises the Madonna, her cyborg double symbolises the Whore of Babylon,[58][59][60] emphasising the virgin-whore binary that women are often subjected to in literature.[61] Metropolis captures the emergence of interest in the 20th century to create an artificial human using science and technology,[62] however it simultaneously represents the fear of the cyborg as humanity's monstrous other.[63]

21st century

[edit]Films

[edit]Black Swan (2010)

[edit]Darren Aronofsky's psychological thriller film Black Swan uses the Gothic double motif to portray the protagonist Nina Sayers' descent into madness as a result of the extreme perfectionism and competitiveness of the New York ballet world.[64] Nina becomes obsessed with obtaining the role of Odette/Odile in a ballet production of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake, pushing herself to her physical and psychological limits in order to achieve her ideal of artistic perfection.[65][66] Nina's rival Lily is represented as her alter ego or shadow self who symbolises repressed aspects of her identity such as her sexuality.[64] While Nina desires to play Odette, the white swan who embodies purity, Lily plays Odile, the evil black swan and dark doppelganger of Odette.[67] The costumes featured in the film enhance the duality between Nina and Lily, as Nina wears childlike white and pink clothes in the beginning of the film whereas Lily wears black clothes. As Nina becomes further absorbed into Lily's identity, she begins to wear darker clothing, as shown in the scene where Nina wears Lily's black lingerie top when they go to a nightclub together, embracing a wild, sexual lifestyle which Nina previously repressed.[67][68]

Subtle references to the Gothic double motif are also present in the film through fragmented images of Nina in mirrors, and Nina encountering doppelgängers of herself on the street, in the bath, and in her bedroom.[69][70] Nina's split personality between the Black Swan and the White Swan has destructive consequences at the end of the film, where she hallucinates in her dressing room before the performance that Lily is taking over the role of Swan Queen, and stabs the double with a shard of mirror, only to realise that she has stabbed herself.[71][72]

Us (2019)

[edit]

Jordan Peele's horror film Us portrays the Wilson family on a vacation near Santa Cruz Beach, whose holiday home is invaded by four intruders who are their exact doubles, wearing red jumpsuits and carrying large scissors.[73][74][75] These doubles are called 'the Tethered,' a class of rebels who live in subterranean tunnels[76] and plan to take the place of their middle-class counterparts who live above ground.[77][74] This Gothic double motif is used in the film to comment on societal inequality and the illusory nature of the American dream, indicating that affluence and success are often achieved at the expense of lower-class people in America, as symbolised by the Tethered who seek revenge on their more prosperous doppelgängers.[78] The Tethered represent the dark Other, or the 'Us and Them' mentality which drives America's societal inequalities.[79] The Tethered also symbolise the fear, hatred, dehumanisation, and negative stereotypes that people of a high socioeconomic status project onto lower-class people, particularly African-Americans.[80]

Racial inequality is a prominent theme in the film, shown when the African-American Wilson family attempt to compete with the status of the white Tyler family. While both families are middle class and both fathers, Gabe Wilson and Josh Tyler, work at the same company, the Tyler family has a higher economic status due to racial privilege. This is shown in the scene where Gabe buys a used boat in an attempt to compete with Josh's private yacht.[81] The Tethered are also used to expose how racism creates a divided identity or split self in African-American people, through the difference between how they perceive themselves and how they are viewed by white people.[82] While the Wilson family attempts to live a conventional middle-class life and live up to the status of the white Tyler family, the invasion of the Tethered, who are their monstrous, grunting lookalikes, represents the shadow of underlying racial bias and reveals how they are perceived by others - monstrous intruders into a social and economic class that people of colour are typically excluded from.[82]

Literature

[edit]Annihilation (2014)

[edit]Jeff VanderMeer’s novel Annihilation, the first in the Southern Reach trilogy, utilizes the Gothic double motif in its portrayal of its characters, particularly the Biologist, to show how Area X has ensnared and entangled them, leading to the character’s physical and mental transformation throughout the novel. As a result of traveling down the Tower, as the Biologist describes it, she becomes contaminated by Area X and begins to experience changes, such as having her senses heightened, and being able to resist the Psychologist’s hypnosis that she continually places on the rest of the group.[83] As these changes happen, the Biologist describes herself as no longer being a biologist but something new, and she asserts that she sees “with such new eyes.”[84] This use of Gothic doubling is unique in that it also connects with the Anthropocene epoch and what has been called Anthropocene literature or the Anthropocene genre. Rather than a physical double that stands separate from her, the Biologist’s doubling is entirely psychological and internal, with Area X’s minuscule bacteria changing her and projecting back onto her. This leads to a division in the Biologist, between that of her ‘human’ identity/personality, and the way she views the world and environment. Later in the novel, when the Biologist finds and reads from her dead husband’s journal, she notes his recount of seeing someone who was not him but resembled him coming out of the Tower.[85] This doppelganger, a physical embodiment of the Gothic double motif, is assumed to be who came back home from Area X, not actually her husband, and is suggested to be how Area X defends itself against humans. By transforming humans that cross its borders, and sending doppelgangers back in their place, Area X continues to survive and grow with each passing year.

The Gothic motif of doubling that is used in Annihilation also connects closely with real and new scientific discoveries regarding bacteria and DNA. In the book, Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, it is described how horizontal DNA has shown that “genetic material from bacteria sometimes ends up in the bodies of beetles, that of fungi in Aphids, and that of humans in malaria”[86] and that only about half of the cells in human’s bodies contain a so-called ‘human genome.’[87] Taking these scientific breakthroughs with the way that the Gothic motif is represented in Annihilation, doubling is represented in the novel as being a tool to show the interconnection between humans and the environment, as well as potentially argue for the environment as holding more power and control over humans than previously thought.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Luckhurst, Roger (2021). Gothic : an illustrated history. Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-25251-2. OCLC 1292078562.

- ^ a b Aguirre, Manuel (1998). Bloom, Clive (ed.). "On Victorian Horror". Gothic Horror: A Reader's Guide from Poe to King and Beyond: 214. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-26398-1. ISBN 978-0-333-68398-9.

- ^ a b c d Diederich, Nicole (2010). "Gothic Doppelgangers and Discourse: Examining the Doubling Practice of (re)marriage in Jane Eyre". Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies. 6 (3): 5.

- ^ Webber, Andrew J. (1996-06-27), "Gothic Revivals: The Doppelgänger in the Age of Modernism", The Doppelgänger, Oxford University Press, pp. 317–357, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198159049.003.0006, ISBN 978-0-19-815904-9

- ^ a b Beauman, Sally. “Afterward.” In Rebecca, Virago Press, 2015, pp. 432.

- ^ Boronska, M. (2016). ‘Facing the repressed: The doubles in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010)’, in Literary and Cultural Forays Into the Contemporary, vol. 15, pp. 103, doi:10.3726/b10721

- ^ a b Groom. (2014). Gothic and Celtic Revivals. In A Companion to British Literature (pp. 361–379). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 365, doi:10.1002/9781118827338.ch74

- ^ "Fetch, n.2". Oxford English Dictionary. December 1989. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ "Irish Word of the Week: Chapter 3 - Irish Arts Center". irishartscenter.org. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Yeats, W. B. (2016). Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry. In Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry. Newburyport: Open Road Integrated Media, Inc, pp. 108.

- ^ a b c d Boos, Sonja (2021), "Fiction's Scientific Double: Hallucinations in Jean Paul's Siebenkäs", The Emergence of Neuroscience and the German Novel, Palgrave Studies in Literature, Science and Medicine, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 47–70, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-82816-5_3, ISBN 978-3-030-82815-8, S2CID 244309557, retrieved 2022-05-03

- ^ Webber, Andrew (1996). The Doppelgänger : double visions in German literature. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-167346-7. OCLC 252646732.

- ^ a b c Bloom, Clive, ed. (1998). Gothic Horror. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-26398-1. ISBN 978-0-333-68398-9.

- ^ a b c d e Gilbert, Sandra M.; Gubar, Susan (2020-03-17). The Madwoman in the Attic. Yale University Press. p. 360. doi:10.2307/j.ctvxkn74x. ISBN 978-0-300-25297-2. S2CID 243132746.

- ^ a b c Mulvey-Roberts, Marie, ed. (1998). The Handbook to Gothic Literature. p. 118. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-26496-4. ISBN 978-0-333-67069-9.

- ^ Bronte, Charlotte (2007). Jane Eyre. Vintage. pp. 342–343.

- ^ Czyżewska, & Głąb, G. (2014). Robert Louis Stevenson Philosophically: Dualism and Existentialism within the Gothic Convention. Roczniki Filozoficzne, 62(3), p. 19.

- ^ Czyżewska, & Głąb, G. (2014). Robert Louis Stevenson Philosophically: Dualism and Existentialism within the Gothic Convention. Roczniki Filozoficzne, 62(3), p. 22.

- ^ Campbell. (2014). Women and Sadism in Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: “City in a Nightmare.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, 57(3), 309–323. doi:10.1353/elt.2014.0040

- ^ Young. (2019). Deadly Nausea and Monstrous Ingestion: Moral-Medical Fantasies in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Victorians : a Journal of Culture and Literature, 135(1), p. 42. doi:10.1353/vct.2019.0009

- ^ Czyżewska, & Głąb, G. (2014). Robert Louis Stevenson Philosophically: Dualism and Existentialism within the Gothic Convention. Roczniki Filozoficzne, 62(3), p. 24.

- ^ Czyżewska, & Głąb, G. (2014). Robert Louis Stevenson Philosophically: Dualism and Existentialism within the Gothic Convention. Roczniki Filozoficzne, 62(3), p. 25.

- ^ Czyżewska, & Głąb, G. (2014). Robert Louis Stevenson Philosophically: Dualism and Existentialism within the Gothic Convention. Roczniki Filozoficzne, 62(3), p. 29.

- ^ Comitini. (2012). The Strange Case of Addiction in Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” Victorian Review, 38(1), p. 117. doi:10.1353/vcr.2012.0052

- ^ Cook. (2020). “The Stain of Breath Upon a Mirror”: The Unitary Self in Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Criticism (Detroit), 62(1), p. 94. doi:10.13110/criticism.62.1.0093

- ^ Comitini. (2012). The Strange Case of Addiction in Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” Victorian Review, 38(1), p. 118. doi:10.1353/vcr.2012.0052

- ^ Cook. (2020). “The Stain of Breath Upon a Mirror”: The Unitary Self in Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Criticism (Detroit), 62(1), p. 96. doi:10.13110/criticism.62.1.0093

- ^ Davidson, C. (2004). “Haunted House/Haunted Heroine: Female Gothic Closets in ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’”, Women's Studies, 33:1, 47-75, p. 59, doi:10.1080/00497870490267197

- ^ Davidson, C. (2004). “Haunted House/Haunted Heroine: Female Gothic Closets in ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’”, Women's Studies, 33:1, 47-75, p. 56, doi:10.1080/00497870490267197

- ^ Battisti, C., & Fiorato, S. (2012). Women's Legal Identity in the Context of Gothic Effacement: Mary Wollstonecraft's Maria or The Wrongs of Woman and Charlotte Perkins Gilman's The Yellow Wallpaper. Pólemos, 6 (2), 183-205, p. 199. doi:10.1515/pol-2012-0012

- ^ Gilman, C. P. (2017). The yellow wallpaper. Open Road Integrated Media, Inc, p. 9.

- ^ Gilman, C. P. (2017). The yellow wallpaper. Open Road Integrated Media, Inc, p. 12.

- ^ Battisti, C., & Fiorato, S. (2012). Women's Legal Identity in the Context of Gothic Effacement: Mary Wollstonecraft's Maria or The Wrongs of Woman and Charlotte Perkins Gilman's The Yellow Wallpaper. Pólemos, 6 (2), p. 198.

- ^ Davidson, C. (2004). “Haunted House/Haunted Heroine: Female Gothic Closets in ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’”, Women's Studies, 33:1, 47-75, p. 62-63, doi:10.1080/00497870490267197

- ^ Battisti, C., & Fiorato, S. (2012). Women's Legal Identity in the Context of Gothic Effacement: Mary Wollstonecraft's Maria or The Wrongs of Woman and Charlotte Perkins Gilman's The Yellow Wallpaper. Pólemos, 6(2), p. 204.

- ^ Gilman, C. P. (2017). The yellow wallpaper. Open Road Integrated Media, Inc, p. 16.

- ^ Selina Jamil (2021) "Imaginative Power" in "The Yellow Wallpaper", ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews, doi:10.1080/0895769X.2021.1895707

- ^ a b Gilman, C. P. (2017). The yellow wallpaper. Open Road Integrated Media, Inc, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Pons, Auba (2013). "Patriarchal Hauntings: Re-Reading Villainy and Gender in Daphne Du Maurier's 'Rebecca.'". Atlantis. 35 (1): 73.

- ^ a b Blackford, Holly (April 2005). "Haunted Housekeeping: Fatal Attractions of Servant and Mistress in Twentieth-Century Female Gothic Literature". Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory. 16 (2): 247. doi:10.1080/10436920590946859. ISSN 1043-6928. S2CID 162245270.

- ^ a b Pyrhonen, Heta (2005). "Bluebeard's Accomplice: 'Rebecca' as a Masochistic Fantasy". Mosaic Winnipeg. 38 (3): 153.

- ^ Beauman, Sally. “Afterward.” In Rebecca, Virago Press, 2015, pp. 430.

- ^ Beauman, Sally. “Afterward.” In Rebecca, Virago Press, 2015, pp. 438.

- ^ Du Maurier, Daphne. Rebecca. Virago Press, 2015, pp. 426.

- ^ MacDonald. (2019). The Mechanization of Desire in Fritz Langs Metropolis. Film Matters, 10(3), p. 191. doi:10.1386/fm_00039_7

- ^ a b Benesch. (1999). Technology, Art, and the Cybernetic Body: The Cyborg as Cultural Other in Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” and Philip K. Dick’s “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” Amerikastudien, 44(3), p. 383.

- ^ Clarke. (2015). “Metropolis, blood and soil: the heart of a heartless world.” GeoJournal, 80(6), p. 823. doi:10.1007/s10708-015-9649-z

- ^ Benesch. (1999). Technology, Art, and the Cybernetic Body: The Cyborg as Cultural Other in Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” and Philip K. Dick’s “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” Amerikastudien, 44(3), p. 382.

- ^ MacDonald. (2019). The Mechanization of Desire in Fritz Langs Metropolis. Film Matters, 10(3), p. 195. doi:10.1386/fm_00039_7

- ^ Clarke. (2015). “Metropolis, blood and soil: the heart of a heartless world.” GeoJournal, 80(6), p. 828. doi:10.1007/s10708-015-9649-z

- ^ Borbély. (2012). Metropolis (An Analysis). Caietele Echinox, 23, p. 211.

- ^ Cowan. (2007). The heart machine: “Rhythm” and body in Weimar film and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Modernism/modernity (Baltimore, Md.), 14(2), p. 237. doi:10.1353/mod.2007.0030

- ^ Borbély. (2012). Metropolis (An Analysis). Caietele Echinox, 23, p. 212.

- ^ Cowan. (2007). The heart machine: “Rhythm” and body in Weimar film and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Modernism/modernity (Baltimore, Md.), 14(2), p. 241. doi:10.1353/mod.2007.0030

- ^ Julie Wosk. (2010). “Metropolis.” Technology and Culture, 51(2), p. 403.

- ^ Cowan. (2007). The heart machine: “Rhythm” and body in Weimar film and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Modernism/modernity (Baltimore, Md.), 14(2), p. 242. doi:10.1353/mod.2007.0030

- ^ Clarke. (2015). “Metropolis, blood and soil: the heart of a heartless world.” GeoJournal, 80(6), p. 830. doi:10.1007/s10708-015-9649-z

- ^ Borbély. (2012). Metropolis (An Analysis). Caietele Echinox, 23, p. 214.

- ^ Bergvall. (2012). Apocalyptic Imagery in Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis.” Literature Film Quarterly, 40(4), 246–257.

- ^ Julie Wosk. (2010). “Metropolis.” Technology and Culture, 51(2), p. 407.

- ^ Julie Wosk. (2010). “Metropolis.” Technology and Culture, 51(2), p. 406.

- ^ Benesch. (1999). Technology, Art, and the Cybernetic Body: The Cyborg as Cultural Other in Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” and Philip K. Dick’s “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” Amerikastudien, 44(3), p. 388.

- ^ a b Landwehr, M. J. (2021). Aronofsky’s 0RW1S34RfeSDcfkexd09rT2black swan1RW1S34RfeSDcfkexd09rT2 as a postmodern fairy tale: Mirroring a narcissistic society. Humanities, 10(3), p.2. doi:10.3390/h10030086

- ^ Landwehr, M. J. (2021). Aronofsky’s 0RW1S34RfeSDcfkexd09rT2black swan1RW1S34RfeSDcfkexd09rT2 as a postmodern fairy tale: Mirroring a narcissistic society. Humanities, 10(3), p.3. doi:10.3390/h10030086

- ^ Amanda Martin Sandino (2013) On perfection: Pain and arts-making in Aronofsky's Black Swan, Journal of Visual Art Practice, 12:3, p.306, doi:10.1080/14702029.2013.10820084

- ^ a b Landwehr, M. J. (2021). Aronofsky’s 0RW1S34RfeSDcfkexd09rT2black swan1RW1S34RfeSDcfkexd09rT2 as a postmodern fairy tale: Mirroring a narcissistic society. Humanities, 10(3), p.4. doi:10.3390/h10030086

- ^ Boronska, M. (2016). ‘Facing the repressed: The doubles in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010)’, in Literary and Cultural Forays Into the Contemporary, vol. 15, pp. 107, doi:10.3726/b10721

- ^ Amanda Martin Sandino (2013) On perfection: Pain and arts-making in Aronofsky's Black Swan, Journal of Visual Art Practice, 12:3, p. 309, doi:10.1080/14702029.2013.10820084

- ^ Boronska, M. (2016). ‘Facing the repressed: The doubles in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010)’, in Literary and Cultural Forays Into the Contemporary, vol. 15, pp. 106, doi:10.3726/b10721

- ^ Amanda Martin Sandino (2013) On perfection: Pain and arts-making in Aronofsky's Black Swan, Journal of Visual Art Practice, 12:3, 308-309, doi:10.1080/14702029.2013.10820084

- ^ Boronska, M. (2016). ‘Facing the repressed: The doubles in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010)’, in Literary and Cultural Forays Into the Contemporary, vol. 15, pp. 108, doi:10.3726/b10721

- ^ Jeffries, J.L. (2020). ‘Jordan Peele (Dir.), Us (Motion Picture), Universal Pictures: A Monkey Paw Production, 2019; Running Time, 1 Hour 56 Min’, Journal of African American Studies (New Brunswick, N.J.), vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 288, doi:10.1007/s12111-020-09470-x

- ^ a b Luckhurst, Roger. Gothic: An Illustrated History. Thames & Hudson, 2021, p. 267.

- ^ Booker, & Daraiseh, I. (2021). “Lost in the funhouse: Allegorical horror and cognitive mapping in Jordan Peele’s Us.” Horror Studies, 12(1), 120. doi:10.1386/host_00032_1

- ^ Simenson. (2020). “Get Out (2017), Us (2019), and Jordan Peele’s New Black Body Horror.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, pp. 35.

- ^ Booker, & Daraiseh, I. (2021). “Lost in the funhouse: Allegorical horror and cognitive mapping in Jordan Peele’s Us.” Horror Studies, 12(1), 121. doi:10.1386/host_00032_1

- ^ Booker, & Daraiseh, I. (2021). “Lost in the funhouse: Allegorical horror and cognitive mapping in Jordan Peele’s Us.” Horror Studies, 12(1), 125. doi:10.1386/host_00032_1

- ^ Booker, & Daraiseh, I. (2021). “Lost in the funhouse: Allegorical horror and cognitive mapping in Jordan Peele’s Us.” Horror Studies, 12(1), 128. doi:10.1386/host_00032_1

- ^ Simenson. (2020). “Get Out (2017), Us (2019), and Jordan Peele’s New Black Body Horror.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, pp. 36.

- ^ Olafsen. (2020). “It’s Us:” Mimicry in Jordan Peele’s Us. Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, 20, pp. 21. doi:10.17077/2168-569X.1546

- ^ a b Simenson. (2020). “Get Out (2017), Us (2019), and Jordan Peele’s New Black Body Horror.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, pp. 38.

- ^ VanderMeer, Jeff (2014). Annihilation. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 25–28. ISBN 978-0374104092.

- ^ VanderMeer, Jeff (2014). Annihilation. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 89. ISBN 978-0374104092.

- ^ VanderMeer, Jeff (2014). Annihilation. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0374104092.

- ^ McFall-Ngai, Margaret (2017). "Noticing Microbial Worlds: The Postmodern Synthesis in Biology". In Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt (ed.). Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. MN: University of Minnesota Press. pp. M55. ISBN 978-1517902377.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F (2017). "Holobiont By Birth: Multilineage Individuals as the Concretion of Cooperative Processes". In Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt (ed.). Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. MN: University of Minnesota Press. pp. M75. ISBN 978-1517902377.