Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ingria

View on WikipediaYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (January 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Ingria[a] is a historical region in what is now northwestern European Russia. It lies along the southeastern shore of the Gulf of Finland, bordered by Lake Ladoga on the Karelian Isthmus in the north and by the River Narva on the border with Estonia in the west. The earliest known modern inhabitants of the region were indigenous Finnic ethnic groups, primarily the Izhorians and Votians, who converted to Eastern Orthodoxy over several centuries during the late Middle Ages. They were later joined by the Ingrian Finns, descendants of 17th century Lutheran Finnish immigrants to the area. At that time, modern Finland proper and Ingria were both part of the Swedish Empire.

Key Information

Ingria as a whole never formed a separate state; however, North Ingria was an independent state for just under two years in 1919–1920. The inhabitants of Ingria cannot be said to have comprised a distinct nation, since the population is made up of several different ethnic groups, despite the Soviet Union recognizing Ingrian as a nationality. The indigenous peoples of Ingria, like the Votians and Izhorians, are today close to extinction, together with their languages. This notwithstanding, many people still recognize and attempt to preserve their Ingrian heritage.[1]

Historic Ingria covers approximately the same area as the Gatchinsky, Kingiseppsky, Kirovsky, Lomonosovsky, Tosnensky, Volosovsky and Vsevolozhsky districts of modern Leningrad Oblast as well as the city of Saint Petersburg.

History

[edit]

In the Viking era (late Iron Age), from the 750s onwards, Ladoga served as a bridgehead on the Varangian trade route to Eastern Europe. A mixed slavic-varangian aristocracy developed that would ultimately rule over Novgorod and Kievan Rus'. In the 860s, the warring Finnic and Slavic tribes rebelled under Vadim the Bold, but later asked the Varangians under Rurik to return and to put an end to the recurring conflicts between them.[2]

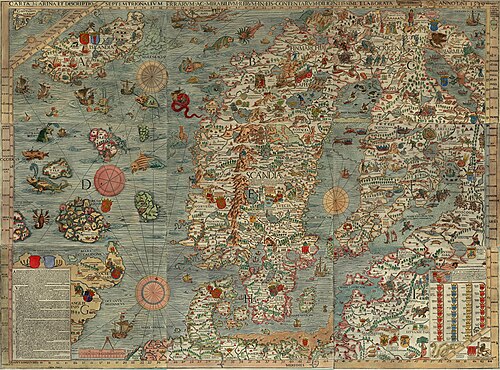

The Swedes referred to the ancient Novgorodian land of Vod people as Ingermanland, Latinized to Ingria. The origin of the name is uncertain, but there are several possible explanations. One explanation is that the name comes from the River Inger, a southern tributary of the Neva River. Another explanation is based on the Norwegian Eymund's saga, which tells the story of the Swedish princess Ingegerd Olofsdotter, who married Yaroslav the Wise, Grand Prince of Novgorod and Kiev in 1019. According to the saga, she received Ladoga and the surrounding lands as a wedding gift from Yaroslav, and the region came to be known as Ingegerd’s land, or Ingermanland.[3] The lands were administered by Swedish jarls, such as Ragnvald Ulfsson, under the sovereignty of the Novgorod Republic.

In the 12th century, Western Ingria was absorbed by the Novgorod Republic. There followed centuries of frequent wars, chiefly between Novgorod and Sweden, and occasionally involving Denmark and Teutonic Knights as well. The Teutonic Knights established a stronghold in the town of Narva, followed by the Russian castle Ivangorod on the opposite side of the Narva River in 1492.

With the consolidation of the Kievan Rus and the expansion of the Republic of Novgorod north, the indigenous Ingrians became Eastern Orthodox. Ingria became a province of Sweden in the Treaty of Stolbovo in 1617 that ended the Ingrian War, fought between Sweden and Russia. After the Swedish conquest of the area in 1617 the Ingrian Finns, descendants of 17th-century Lutheran emigrants from present-day Finland, became the majority in Ingria. In 1710, following a Russian conquest, Ingria was designated as the Province of St. Petersburg.

In the Treaty of Nystad in 1721, Sweden formally ceded Ingria to Russia.

In 1927 the Soviet authorities designated the area as Leningrad Province. Deportations of the Ingrian Finns started in late 1920s, and Russification was nearly complete by the 1940s.

In the modern era, Ingria forms the northwestern anchor of Russia—its "window" on the Baltic Sea—with Saint Petersburg as its centre.

Swedish Ingria

[edit]Although Sweden and Novgorod had fought for the Ingrian lands more or less since the Great Schism of 1054, the first actual attempt to establish Swedish dominion in Ingria appears to date from the early 14th century, when Sweden first founded the settlement of Viborg in Karelia[4] and then the fortress Landskrona (built in 1299 or 1300) at the confluence of the Ohta and Neva rivers. However, Novgorod re-conquered Landskrona in 1301 and destroyed it. Ingria eventually became a Swedish dominion in the 1580s, but the Treaty of Teusina (1595) returned it to Russia in 1595. Russia in its turn ceded Ingria to Sweden in the Treaty of Stolbova (1617) after the Ingrian War of 1610–1617. Sweden's interest in the territory was mainly strategic: the area served as a buffer zone against Russian attacks on the Karelian Isthmus and on present-day Finland, then the eastern half of the Swedish realm; and Russian Baltic trade had to pass through Swedish territory. The townships of Ivangorod, Jama (now Kingisepp), Caporie (now Koporye) and Nöteborg (now Shlisselburg) became the centres of the four Ingrian counties (slottslän), and consisted of citadels, in the vicinity of which were small boroughs called hakelverk – before the wars of the 1650s mainly inhabited by Russian townspeople. The degree to which Ingria became the destination for Swedish deportees has often been exaggerated.[by whom?]

Ingria remained sparsely populated. In 1664 the total population amounted to 15,000. Swedish attempts to introduce Lutheranism, which accelerated after an initial period of relative religious tolerance,[5] met with repugnance on the part of the majority of the Orthodox peasantry, who were obliged to attend Lutheran services; converts were promised grants and tax reductions, but Lutheran gains were mostly due to voluntary resettlements by Finns from Savonia and Finnish Karelia (mostly from Äyräpää).[1][6] The proportion of Lutheran Finns in Ingria (Ingrian Finns) comprised 41.1% in 1656, 53.2% in 1661, 55.2% in 1666, 56.9% in 1671 and 73.8% in 1695, the remainder being Russians,[6] Izhorians and Votes.[7] Ingermanland was to a considerable extent enfiefed to noble military and state officials, who brought their own Lutheran servants and workmen. However, a small number of Russian Orthodox churches remained in use until the very end of the Swedish dominion, and the forceful conversion of ethnic Russian Orthodox forbidden by law.[8]

Nyen became the main trading centre of Ingria, especially after Ivangorod dwindled, and in 1642 it was made the administrative centre of the province. In 1656 a Russian attack badly damaged the town, and the administrative centre moved to Narva.[1]

Russian Ingria

[edit]

In the early 18th century the area was reconquered by Russia in the Great Northern War after having been in Swedish possession for about 100 years. Near the location of the Swedish town Nyen, close to the Neva river's estuary at the Gulf of Finland, the new Russian capital Saint Petersburg was founded in 1703.

Peter the Great raised Ingria to the status of a duchy with Prince Menshikov as its first (and last) duke. In 1708, Ingria was designated a governorate (Ingermanland Governorate in 1708–1710, Saint Petersburg Governorate in 1710–1914, Petrograd Governorate in 1914–1924, Leningrad Governorate in 1924–1927).

In 1870, printing started of the first Finnish-language newspaper in Ingria, Pietarin Sanomat. Before that Ingria received newspapers mostly from Viborg. The first public library was opened in 1850 in Tyrö. The largest of the libraries, situated in Skuoritsa, had more than 2,000 volumes in the second half of the 19th century. In 1899 the first song festival in Ingria was held in Puutosti (Skuoritsa).[1]

By 1897 (year of the Russian Empire Census) the number of Ingrian Finns had grown to 130,413, and by 1917 it had exceeded 140,000 (45,000 in Northern Ingria, 52,000 in Central (Eastern) Ingria and 30,000 in Western Ingria, the rest in Petrograd).

From 1868 Estonians began to migrate to Ingria as well. In 1897 the number of Estonians inhabiting the Saint Petersburg Governorate reached 64,116 (12,238 of them in Saint Petersburg itself); by 1926 it had increased to 66,333 (15,847 of them in Leningrad).

As to Izhorians, in 1834 there were 17,800 of them, in 1897—21,000, in 1926—26,137. About 1000 Ingrians lived in the area ceded to Estonia under the Peace Treaty of Tartu (1920).[1]

Estonian Ingria

[edit]

Under the Russian-Estonian Peace Treaty of Tartu of 1920, a small part of West Ingria became part of the Republic of Estonia. In contrast to other parts of Ingria, Finnish culture blossomed in this area, known as Estonian Ingria. This was to a large extent due to the work of Leander Reijo (also Reijonen or Reiju) from Kullankylä on the new border between Estonia and the Soviet Union, who was called "The King of Ingria" by the Finnish press. Finnish schools and a Finnish newspaper were started. A church was built in Kallivieri in 1920 and by 1928 the parish had 1,300 people.[9][10]

In 1945, after the Second World War, Estonian Ingria, then in the Soviet Union, was transferred to the Russian SFSR and incorporated into the Leningrad Oblast. Since Estonia reclaimed its independence in 1991, this territory has been disputed. As Russia does not recognize the Treaty of Tartu, the area currently remains under Russian control.[citation needed]

Soviet Ingria

[edit]

After the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia, the Republic of North Ingria (Finnish: Pohjois-Inkerin tasavalta) declared its independence from Russia with the support of Finland and with the aim of incorporation into Finland. It ruled parts of Ingria from 1919 until 1920. With the Russian-Finnish Peace Treaty of Tartu it was re-integrated into Russia, but enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy.

At its height in the 1920s, there were about 300 Finnish language schools and 10 Finnish language newspapers in Ingria.[11]

The First All-Union Census of the Soviet Union in 1926 recorded 114,831 Leningrad Finns, as Ingrian Finns were called.[1] The 1926 census also showed that the Russian population of central Ingria outnumbered the Finnic peoples living there, but Ingrian Finns formed the majority in the districts along the Finnish border.[6]

In the early 1930s the Izhorian language was taught in the schools of the Soikinsky Peninsula and the area around the mouth of the Luga River.[1]

In 1928 collectivization of agriculture started in Ingria. To facilitate it, in 1929–1931, 18,000 people (4320 families), kulaks (independent peasants) from North Ingria, were deported to East Karelia, the Kola Peninsula as well as Kazakhstan and Central Asia.

The situation for the Ingrian Finns deteriorated further when in the fall of 1934 the Forbidden Border Zone along the western border of the Soviet Union was established, where entrance was forbidden without special permission issued by the NKVD. It was officially only 7.5 km (5 miles) deep initially, but along the Estonian border it extended to as much as 90 km (60 miles). The zone was to be free of Finnic and some other peoples, who were considered politically unreliable.[6][12] On 25 March 1935, Genrikh Yagoda authorized a large-scale deportation targeting Estonian, Latvian and Finnish kulaks and lishentsy residing in the border regions near Leningrad. About 7,000 people (2,000 families) were deported from Ingria to Kazakhstan, Central Asia and the Ural region. In May and June 1936 the entire Finnish population of the parishes of Valkeasaari, Lempaala, Vuole and Miikkulainen near the Finnish border, 20,000 people, were resettled to the areas around Cherepovets and Siberia in the next wave of deportations. In Ingria they were replaced with people from other parts of the Soviet Union, mostly Russians but also Ukrainians and Tatars.[1][6]

In 1937 Lutheran churches and Finnish and Izhorian schools in Ingria were closed down and publications and radio broadcasting in Finnish and Izhorian were suspended.

Both Ingrian Finnish and Izhorian populations all but disappeared from Ingria during the Soviet period. 63,000 fled to Finland during World War II, and were required back by Stalin after the war. Most became victims of Soviet population transfers and many were executed as "enemies of the people".[1][6][12] The remainder, including some post-Stalin returnees (it was not until 1956 that some of the deported were allowed to return to their villages), were outnumbered by Russian immigration.

The 1959 census recorded 1,062 Izhorians; in 1979 that number had fallen to 748, only 315 of them around the mouth of the Luga River and on the Soikinsky Peninsula. According to the Soviet census of 1989, there were 829 Izhorians, 449 of them in Russia (including other parts of the country) and 228 in Estonia.[1]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kurs, Ott (1994). "Ingria: The broken landbridge between Estonia and Finland". GeoJournal 33.1, 107–113.

- ^ Alfred Rambaud (1970). History of Russia from the Earliest Times to 1882. Vol. 1. AMS Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-04-04-05230-0.

- ^ "Inkerinmaa". Inkeri ja inkeriläisyys (in Finnish). Finnish Literature Society. Retrieved 21 February 2025.

- ^ Åström Anna-Maria; Korkiakangas Pirjo; Olsson Pia (2018). Memories of My Town: The Identities of Town Dwellers and their Places in Three Finnish Towns. Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura. p. 67. ISBN 978-95-17-46433-8.

- ^ Pereswetoff-Morath, A. (2003). "'Otiosorum hominum receptacula': Orthodox Religious Houses in Ingria, 1615–52". Scando-Slavica. 49 (1): 105–129. doi:10.1080/00806760308601195.

- ^ a b c d e f Matley, Ian M. (1979). "The Dispersal of the Ingrian Finns". Slavic Review. 38 (1): 1–16. doi:10.2307/2497223. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2497223.

- ^ Inkeri. Historia, kansa, kulttuuri. Edited by Pekka Nevalainen and Hannes Sihvo. Helsinki 1991.

- ^ Daniel Rancour-Laferriere (2000). Russian Nationalism from an Interdisciplinary Perspective: Imagining Russia. E. Mellen Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-07-73-47671-4.

- ^ Johannes Angere, Kullankylä (1994) Swedish magazine Ingria. (4), pages 6–7

- ^ Johannes Angere, Min hemtrakt (2001) Swedish magazine Ingria (2), pages 12–13.

- ^ "Inkerinsuomalaisten kronikka", Tietoa Inkerinsuomalaisista (Information about Ingrian Finns), archived at the Wayback Machine, 13 February 2008 (in Finnish)

- ^ a b Martin, Terry (1998). "The Origins of Soviet Ethnic Cleansing" (PDF). The Journal of Modern History. 70 (4): 813–61. doi:10.1086/235168. ISSN 1537-5358. JSTOR 10.1086/235168. S2CID 32917643.

Further reading

[edit]- Kurs, Ott (1994). Ingria: The broken landbridge between Estonia and Finland. GeoJournal 33.1, 107–113.

- Kepsu, Kasper. 2017. The Unruly Buffer Zone: The Swedish province of Ingria in the late 17th century. Scandinavian Journal of History.

- Site of the Ingrian Cultural Society in Helsinki

- Ingermanland and St-Petersburg

- Kyösti Väänänen (1987), Herdaminne för Ingermanland. 1, Lutherska stiftsstyrelsen, församlingarnas prästerskap och skollärare i Ingermanland under svenska tiden / Kyösti Väänänen., Skrifter utgivna av Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland (in Swedish), Helsinki: Society of Swedish Literature in Finland, ISSN 0039-6842, Wikidata Q113529885

- Kyösti Väänänen; Georg Luther (2000), Herdaminne för Ingermanland. 2, De finska och svenska församlingarna och deras prästerskap 1704-1940 / Georg Luther., Skrifter utgivna av Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland (in Swedish), Helsinki: Society of Swedish Literature in Finland, ISSN 0039-6842, Wikidata Q113529971

Ingria

View on GrokipediaIngria is a historical region in northwestern European Russia, encompassing the isthmus between the southeastern Gulf of Finland, the Neva River system, and Lake Ladoga, now largely within Saint Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast.[1][2] The area, long a strategic landbridge linking Estonia and Finland, was initially controlled by the Novgorod Republic and sparsely populated by indigenous Baltic Finnic groups such as the Votians and Izhorians.[3][4] Swedish annexation via the 1617 Treaty of Stolbovo prompted settlement by Finnish-speaking Lutherans from Savo and the Karelian Isthmus, forming the Ingrian Finns who became the region's predominant ethnic group by the late 17th century.[3][4] Russia reclaimed Ingria during the Great Northern War (1700–1721), with Peter the Great establishing Saint Petersburg in 1703 as a new imperial capital, shifting demographics toward Russification.[3][2] The Ingrian population peaked at around 130,000 in the early 20th century but faced severe decline through Soviet deportations—totaling over 97% by 1956—and wartime displacements, resulting in assimilation, linguistic erosion, and diaspora.[3][1][4]

Geography

Location and Physical Features

Ingria comprises the historical territory bounded by the southeastern shores of the Gulf of Finland to the west, Lake Ladoga to the east, and the Neva River system originating from Lake Ladoga.[3] This positioning grants the region direct maritime access to the Baltic Sea through the Gulf of Finland and fluvial connections via the Neva River, which flows approximately 74 kilometers westward from Lake Ladoga to its delta.[5] The physical terrain features flat coastal plains and low-lying marshy lowlands, characteristic of the broader northwestern Russian landscape. Dense forests, primarily coniferous, cover much of the interior, interspersed with river valleys and wetlands formed by the Neva and its tributaries.[3] Natural features include extensive timber resources from taiga forests, fisheries supported by the nutrient-rich waters of the Gulf of Finland, Neva delta, and Lake Ladoga, as well as arable plains suitable for cultivation in unglaciated areas.[3][6]Climate and Natural Resources

Ingria possesses a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb) moderated by proximity to the Gulf of Finland, resulting in relatively mild winters compared to interior Russia but with persistent humidity and frequent precipitation. Annual average temperatures hover around 5.5 °C, with January means of -6 °C featuring prolonged cold spells, snow cover lasting 120-150 days, and occasional thaws influenced by maritime air masses. Summers are cool and temperate, with July averages of 17-18 °C, though daytime highs rarely exceed 25 °C amid cloudy, rainy conditions that contribute to high relative humidity levels often surpassing 80%. Precipitation totals approximately 660-700 mm yearly, distributed unevenly with peaks in late summer and autumn, rendering the low-lying terrain susceptible to seasonal flooding, particularly along the Neva River delta where water levels can rise dramatically due to storm surges from the Baltic Sea.[7][8] The region's natural resources underpin its habitability through provision of timber, water, and minerals, though extraction has historically altered landscapes via drainage and clearing. Forests dominate much of the terrain, comprising coniferous species like pine and spruce in a taiga extension, supporting biomass accumulation and carbon sequestration estimated at significant levels in northwestern Russia's wooded peatlands. Rivers form a dense network exceeding 50,000 km in total length across the broader Leningrad area, including the Neva (74 km within the region), Luga (353 km), and Oyat (266 km), enabling hydropower potential—though actual capacity remains modest due to flat topography—and facilitating drainage in boggy soils. Mineral deposits include bauxites for aluminum production, phosphorites for fertilizers, glass sands, and carbonate rocks, with over 80 sites exploited, contributing to industrial viability without reliance on deep mining. These elements, combined with wetland mires, have sustained limited agriculture and fuel sources like combustible shales, but extensive historical drainage for settlement has reduced wetland coverage and increased erosion risks.[9][10][11]Etymology

Origins and Historical Usage

The name Ingria derives from the Latinized form Ingria, which stems from the medieval Swedish designation Ingermanland for the region south of the Gulf of Finland. Etymological theories propose a connection to Ingegerd Olofsdotter, daughter of King Olof Skötkonung of Sweden, who married Grand Prince Yaroslav I of Kiev around 1019 and reportedly received lands near Lake Ladoga—potentially influencing the Swedish naming convention upon later conquests. Alternative derivations link Ingermanland to Finnic hydronyms such as Inger or Inkere, reflecting local river names associated with the indigenous peoples.[3][12] In early Russian sources, the territory was attested as Izhora land (Izhorskaya zemlya) by the 12th century, deriving from the Izhorians (Izhoryane), a Finnic ethnic group native to the area, with references appearing in Novgorodian chronicles describing regional conflicts and settlements. The term Ingariya and its inhabitants Ingaros emerge in a 1220 chronicle entry, while the Chronicle of Livonia mentions Ingardia in 1221 amid Crusader expeditions. These early usages distinguished the Izhora-inhabited zone from adjacent Votic territories.[13][14] Linguistic variations persisted across European languages, including German Ingermanland and Russian Ingermanlandiya or Ingeriya. The Swedish form Ingermanland gained formal diplomatic prominence in the Treaty of Nystad on September 10, 1721, which concluded the Great Northern War and transferred Swedish control of the province—explicitly named as such—to the Russian Empire, marking a key historical codification of the toponym.[15][16]Peoples and Ethnicity

Indigenous Finnic Groups

The indigenous Finnic groups of Ingria comprise the Izhorians and Votians, Baltic Finnic peoples whose presence predates Slavic incursions into the region during the medieval period. These groups speak languages from the Finnic branch of the Uralic family, reflecting a distinct linguistic and cultural continuity amid later demographic pressures. Historical records and toponymic evidence attest to their long-standing settlements, primarily oriented around fishing, small-scale agriculture, and forestry in the marshy lowlands and coastal areas.[17][18] Izhorians, native to the western Ingria between the Narva River and the Neva River along the Gulf of Finland, represent one core indigenous population. Their eponymous language, also called Izhorian or Ingrian, features three main dialects and survives in severely endangered form, with fewer than 100 fluent native speakers documented in recent linguistic surveys. Ethnographic accounts describe traditional Izhorian communities as semi-nomadic fishers who adopted Eastern Orthodox Christianity following Novgorod's expansion in the 12th-13th centuries, though pre-Christian animistic practices persisted into the early modern era. Archaeological sites, including Iron Age burial grounds and coastal habitations, underscore transitions from hunter-gatherer subsistence to more settled economies by the first millennium AD.[19] Votians, or Votes, occupy southern Ingria, centered in the vicinity of present-day Kingisepp. Their Votic language, closely related to Livonian and Estonian, is nearly extinct, with only isolated elderly speakers remaining as of the early 21st century and revitalization efforts yielding limited success. Referred to collectively with other Finnic tribes as "Chud" in early East Slavic chronicles from the 9th-12th centuries, Votians maintained autonomous villages amid tribute relations with Novgorod, engaging in rye cultivation and riverine trade. Genetic and folkloric studies highlight their assimilation challenges, including language shift to Russian by the 20th century, yet distinct folklore elements like epic songs preserve pre-Slavic cultural markers.[20][21][22] The ancient Chud designation in Russian primary sources encompasses ancestral Finnic populations, including proto-Izhorians and Votians, encountered during Novgorod's northeastern campaigns around 860-1130 AD. This term denoted non-Slavic tribes in Ingria and adjacent territories like Estonia and Karelia, often portrayed in annals as tributaries or adversaries in conflicts over trade routes. While no discrete modern Chud ethnicity endures, linguistic substrate in Ingrian toponyms—such as those incorporating Finnic roots for water bodies and forests—evidences their foundational role in the region's pre-medieval ethnolinguistic landscape.[20][21] In contrast, Ingrian Finns, ethnic Finns from Savo and other Finnish regions, arrived as Lutheran settlers under Swedish administration in the 17th century, populating depopulated areas post-Russian conquests; they do not qualify as indigenous but augmented the Finnic demographic baseline before Russian imperial reassertion.[3]Historical Demographic Shifts

During the period of Swedish administration from 1617 to 1721, policies actively promoted the settlement of Lutheran Finns from regions such as Savo and Karelia to repopulate the area and strengthen Protestant influence against the remaining Orthodox Russian elements. This influx significantly altered the ethnic composition, with Finnish speakers increasing their share in rural areas from around 41% in 1656 to over 55% by the late 17th century. A tax census from that era documented 58,979 peasants in Ingria, including 22,986 Finns (approximately 39%) and 14,511 Izhorians (a Finnic indigenous group, about 25%), alongside 5,883 ethnic Russians (10%), indicating Finnic groups formed the rural majority.[23] The Russian conquest during the Great Northern War (1700–1721), culminating in the capture of Ingria by 1703, led to drastic population losses from combat, famine, and flight, reducing the estimated inhabitants from roughly 100,000 to 20,000–30,000 by war's end. Peter the Great's founding of Saint Petersburg in 1703 initiated a reversal of migration patterns, drawing Slavic peasants from interior Russia to farm depopulated lands granted by nobles, as well as Baltic Germans and other Europeans for administrative and technical roles. This resettlement rapidly elevated the Slavic proportion, with Russians becoming the dominant group by the mid-18th century as the city's growth attracted further laborers and the province's total population recovered to over 200,000 by 1760.[24] In the 19th and early 20th centuries, imperial policies favoring Russian settlement—through land reforms, military colonization, and administrative preferences—accelerated the displacement and assimilation of Finnic communities, compounded by natural population growth among incoming Slavs and urbanization pulling residents to Saint Petersburg. Linguistic and cultural Russification efforts under tsars like Alexander III further eroded Finnic identity via school curricula and church reforms prioritizing Russian. The 1926 Soviet census recorded 115,200 Ingrian Finns (descendants of the Swedish-era settlers) in Leningrad Oblast, a marked decline from their prior rural dominance, amid a provincial population exceeding 2.9 million dominated by ethnic Russians.[25][26]Contemporary Demographics

The core area of Ingria, comprising Saint Petersburg and the historical southern territories within Leningrad Oblast, had a population of approximately 6 million according to the 2021 All-Russian census conducted by Rosstat.[27] Saint Petersburg, the dominant urban center, accounted for 5,601,911 residents, or over 90% of the region's total, highlighting extreme urban concentration.[27] Rural districts in Leningrad Oblast, by contrast, exhibit ongoing depopulation, with net migration losses and stagnant growth outside major settlements.[28] Ethnic Russians form the overwhelming majority, exceeding 90% across the area; in Leningrad Oblast, they comprised 93.7% (1,642,897 individuals) in the 2021 census.[29] Remaining groups include Ukrainians (0.5%), Belarusians (0.4%), and Central Asian migrants such as Uzbeks (0.4%), reflecting post-Soviet labor inflows.[29] Indigenous Finnic populations persist as tiny minorities: Ingrian Finns total around 20,000 nationwide, with the vast majority concentrated in Ingria despite assimilation pressures, while Izhorians number just 781.[1] Demographic challenges include rapid aging and sub-replacement fertility; Leningrad Oblast's total fertility rate stood at 0.88 children per woman in recent Rosstat estimates, below the national average and contributing to minority group contraction.[30] Births in the oblast fell to 11,840 in 2024 (5.8 per 1,000 population), underscoring broader trends of low natality among both Russians and Finnic groups. Median age exceeds 40 years regionally, with life expectancy at birth around 73 years, strained by excess mortality in rural zones.[28]Pre-Modern History

Prehistoric Settlement

The earliest evidence of human habitation in Ingria dates to the Mesolithic period, following the retreat of the Pleistocene ice sheets around 10,000 BC, with settled hunter-gatherer communities established by approximately 9,000 BC. Archaeological sites near Lake Ladoga, including those on the adjacent Karelian Isthmus and northwestern shores, yield artifacts such as microliths, adzes, and quartz tools indicative of foraging economies adapted to post-glacial forests, rivers, and lakes. These remains reflect small, mobile groups exploiting fish, game, and wild plants in a landscape shaped by isostatic rebound and marine transgressions. The transition to the Neolithic occurred around 5,300–4,000 BC, marked by the appearance of pottery in the Narva culture, which spanned the eastern Baltic including Ingria's coastal and lacustrine zones. This culture emphasized continued hunter-gatherer subsistence with asbestos-tempered ceramics for cooking and storage, though evidence of rudimentary agriculture—such as emmer wheat and barley cultivation—emerges sporadically by 4,000 BC amid influences from the inland Comb Ceramic culture. Genetic analyses confirm an influx of Eastern hunter-gatherer ancestry during this phase, correlating with expanded ceramic technologies but limited sedentism.[31] By the late Neolithic and into the Bronze Age (circa 3,200–1,800 BC), Corded Ware culture elements, including cord-impressed pottery and battle-axes, indicate broader Indo-European contacts and possible pastoralist incursions, facilitating early animal husbandry and forest clearance.[31] The Iron Age (500 BC–1,000 AD) brought advancements in metallurgy, with local bog iron smelting and imported bronze artifacts signaling technological sophistication. Tarand cemeteries—stone-enclosed grave clusters unique to the eastern Baltic—dot Ingria's landscape, containing cremations, weapons, and jewelry that attest to hierarchical societies. Trade intensified along Gulf of Finland routes, linking communities to Varangian networks by the 8th–10th centuries AD, evidenced by Scandinavian-style brooches and amber exchanges.[31]Medieval Period under Novgorod

In the 9th to 12th centuries, the Novgorod Republic asserted control over Ingria, a marshy region along the Neva River basin populated by Finnic tribes such as the Izhorians and Votes, through military expeditions that enforced tribute payments primarily in squirrel and other furs.[3][32] These campaigns, detailed in the Novgorod First Chronicle, involved subduing resistant groups like the Ves' (ancestors of the Votes) and extracting annual polyud'ye (tribute circuits) via riverine routes, leveraging Ingria's geography of waterways and forests for efficient access to trapping grounds while minimizing overland risks.[32] The tribute system reflected causal ties to the land's resources, sustaining Novgorod's economy without full settlement, as the area remained sparsely populated.[3] Swedish incursions in the early 1240s threatened this northern frontier, prompting Prince Alexander Yaroslavich of Novgorod to mobilize forces against a combined Swedish-Finnish expedition aiming to establish a foothold at the Neva delta.[33] On July 15, 1240, Alexander's troops achieved victory in the Battle of the Neva, ambushing the invaders near the Izhora River mouth and preventing fortification of the strategic estuary, which preserved Novgorod's tribute flows and access to Baltic trade routes.[33][34] This engagement, emphasizing rapid cavalry strikes over pitched battle, underscored Ingria's vulnerability to western powers due to its exposed coastal position.[34] Amid persistent Finnic paganism involving animist rituals and resistance to Slavic authority, Novgorod consolidated influence by founding fortified outposts with Orthodox chapels, such as the early settlement at Staraya Ladoga (established circa 753 but Slavicized under Novgorod by the 9th century) and later centers including Koporye by the 13th century.[35] These installations, per Novgorod chronicles, served dual roles in tax collection and missionary efforts, gradually introducing Eastern Orthodoxy to tribes through elite conversions and church construction, though full Christianization lagged due to geographic isolation and cultural entrenchment.[32][35] By the late medieval period, such outposts numbered four key citadels in Ingermanland (Novgorodian Ingria), anchoring administrative control.[35]Swedish Era

Conquest and Administration

Sweden secured initial control over parts of Ingria during the Livonian War (1558–1583), capturing key fortresses such as Narva in 1581, though the region remained contested amid ongoing Russo-Swedish conflicts.[36] Full acquisition occurred during Russia's Time of Troubles, when Swedish forces under Jacob De la Gardie occupied Novgorod and advanced into Ingria, culminating in the Ingrian War (1610–1617).[37] The conquest was formalized by the Treaty of Stolbovo on February 27, 1617, in which Tsar Michael Romanov ceded Ingria, along with Kexholm and Lappeenranta, to Sweden in exchange for peace and recognition of Russian sovereignty over Novgorod.[38] Under Swedish rule, Ingria was organized as the Province of Ingermanland (Swedish: Ingermanland), divided into administrative districts known as läns, including Nyens län (centered at Nyen), Nöteborgs län (at Noteborg), and Ivangorods län.[39] Governance was headed by a landshövding (governor) appointed by the Swedish crown, who oversaw military, judicial, and fiscal affairs, with local administration often delegated to district chiefs (fogdar) to integrate the province into the Swedish realm while maintaining fortifications against potential Russian incursions.[40] To secure the Neva River trade route, Sweden constructed Fort Nyenskans in 1611 at the confluence with the Okhta River, which served as the nucleus for the town of Nyen and facilitated commerce in timber, tar, and furs, elevating it to the province's administrative center by 1642.[41]Cultural and Economic Developments

During the Swedish administration of Ingria following the Treaty of Stolbovo in 1617, governors actively encouraged immigration of Lutheran Finnish peasants from eastern Finland to repopulate and cultivate the depopulated marshlands and forests, initiating a period of demographic and agricultural expansion that contrasted with the region's prior sparse settlement under Novgorod control. These settlers, primarily from Savo and Karelia, cleared land for rye and barley farming, introducing slash-and-burn techniques adapted to the local terrain, which increased arable output and supported self-sufficient rural communities. By the late 17th century, Finnish immigrants and their descendants formed the majority of the rural population, numbering around 23,000 Finns among approximately 59,000 tax-paying peasants overall, reflecting a tripling from the estimated 15,000–20,000 inhabitants recorded in 1664 amid post-war recovery.[3][23] Economic advancements centered on exploiting Ingria's abundant pine forests for export-oriented industries, with the establishment of sawmills and tar pits transforming the province into a key supplier of naval stores for European shipbuilding. Tar production, derived from slow-burning pine resin, and sawn timber exports surged from ports like Narva, where shipments of hewn and processed wood supplanted earlier tar dominance by the 1680s, contributing to Sweden's Baltic trade revenues amid rising demand from Western Europe. Agricultural surpluses from Finnish settlements complemented these forest-based activities, enabling localized markets and tax revenues that funded infrastructure such as drainage ditches and roads, fostering modest urbanization around fortified towns.[42] Culturally, the influx of Finnish Lutherans entrenched Protestant practices, with the construction of churches and schools promoting literacy in Finnish dialects and Swedish administrative norms, though indigenous Izhorians and Votes—Eastern Orthodox Finnic groups—resisted forced conversions despite edicts enforcing attendance at Lutheran services. The Treaty of Stolbovo's provisions for religious freedom allowed Orthodox natives to retain some customs and clergy initially, mitigating outright revolt, but Swedish policies prioritized assimilation through land grants to Lutheran settlers, gradually eroding pre-existing Finnic pagan-Orthodox traditions in favor of a hybrid rural Lutheran culture. This selective tolerance, combined with exemptions from certain feudal obligations for new farmers, stabilized society but highlighted tensions between colonizers' confessional goals and local ethnic persistence.[23]Russian Imperial Period

Conquest by Peter the Great

The conquest of Ingria by Peter the Great occurred during the Great Northern War (1700–1721), a conflict initiated by Russia's declaration of war against Sweden on 22 February 1700 (Old Style) to secure access to the [Baltic Sea](/page/Baltic Sea).[43] Early Russian efforts met disaster at the Battle of Narva on 20 November 1700 (O.S.), where a Swedish force of approximately 8,000 under King Charles XII routed a Russian army numbering 35,000–40,000, inflicting over 8,000 casualties while suffering fewer than 700 losses; Tsar Peter I escaped but used the defeat to reform his military.[44] Following military reorganization, Russian forces advanced into Ingria. In 1703, troops under Field Marshal Boris Sheremetev captured the Swedish fortress of Nyenskans on the Neva River delta, a strategic position controlling access to the Gulf of Finland.[45] On 16 May 1703 (O.S.), Peter laid the cornerstone of the Peter and Paul Fortress on the site, marking the founding of Saint Petersburg as a fortified outpost to anchor Russian control; construction mobilized tens of thousands of conscripted laborers, including serfs and soldiers, under grueling conditions that claimed numerous lives.[46][47] The Siege of Narva in 1704 further consolidated gains, as a Russian army of about 45,000 under Prince Mikhail Golitsyn invested the city from 27 June to 9 August 1704 (O.S.), compelling the Swedish garrison of roughly 5,000 to surrender after heavy bombardment; Swedish losses exceeded 3,000 dead or wounded plus 1,900 captured, yielding Russia its vital port.[43] These victories expelled Swedish forces from most of Ingria, though fighting persisted elsewhere until the war's resolution. The Treaty of Nystad, signed on 10 September 1721 (New Style), concluded the war and formalized Russian sovereignty over Ingria, ceding the province—along with Estonia and Livonia—from Sweden in perpetuity and establishing Russia as a Baltic power.[48]Integration and Urbanization

Following the conquest of Ingria, Peter I established the Ingermanland Governorate in 1708 as part of administrative reforms dividing Russia into larger provinces, with the region centered around the new fortress at Nyenskans and later St. Petersburg.[49] On June 3, 1710, the governorate was renamed the St. Petersburg Governorate to reflect the prominence of the newly founded capital city.[50] This restructuring facilitated centralized control, integrating the former Swedish territories into the Russian imperial framework through appointed governors overseeing taxation, military recruitment, and local governance.[51] Infrastructure development emphasized connectivity and trade, exemplified by the Ladoga Canal project ordered by Peter I in 1718 and constructed from 1719 to 1731 along the southern shore of Lake Ladoga.[52] The canal, spanning approximately 117 kilometers, aimed to provide a safer inland waterway for vessels avoiding the lake's hazardous open waters, thereby enhancing commercial transport from the Baltic to interior Russia and supporting the economic consolidation of the governorate.[53] These efforts coincided with rapid urbanization, particularly in St. Petersburg, which grew from its 1703 founding to around 220,000 residents by 1800, drawing Russian settlers, laborers, and administrators to bolster the imperial presence.[54] Social integration involved the imposition of serfdom on the local Finnic populations, including Ingrian Finns and Votians, binding them to the land under Russian landlords following the influx of Russian settlers after 1704.[55] This policy, enduring until the 1861 emancipation, contrasted with prior Swedish practices and facilitated agricultural exploitation while promoting Russian Orthodox dominance through state-supported settlement and administrative preferences for the faith over Lutheranism.[55] By the mid-18th century, Russian Orthodox adherents formed the majority in the governorate, reflecting demographic shifts driven by migration and imperial policies.Soviet and Revolutionary Era

Civil War and Early Soviet Policies

Following the October Revolution on November 7, 1917, Bolshevik forces rapidly seized Petrograd, the central city of Ingria, establishing Soviet control over the region to safeguard it against counter-revolutionary threats during the ensuing Civil War.[56] The area served as a strategic buffer, with Red Army units occupying key positions to protect the Bolshevik heartland from White advances and potential Finnish incursions from the north.[56] In 1919, amid the chaos of the Civil War, Ingrian Finns, distrustful of Bolshevik centralization, launched localized uprisings seeking autonomy or alignment with Finland, including an initial seizure of the Kirjasalo customs post in June by 150-200 armed locals, with hopes of external support from Finnish forces.[23] These efforts, bolstered temporarily by White Russian sympathies among some nationalists, were swiftly crushed by Red Army interventions, which reimposed control and conscripted Ingrian males into Bolshevik ranks, exacerbating local resentments.[56] [57] Attempts to declare independent or autonomous Ingrian entities, including proposals for a Soviet-style republic, collapsed under military suppression, preventing any formal separation.[3] Stabilization after the Civil War led to the Treaty of Tartu in October 1920 between Soviet Russia and Finland, which recognized cultural rights for Ingrian Finns, including Finnish-language education and local governance, though administered primarily by pro-Bolshevik "Red Finns" exiled from Finland.[56] In the early 1920s, Soviet nationality policy under korenizatsiya briefly elevated Finnic elements, promoting Finnish as a lingua franca for Ingrian minorities through initiatives like the establishment of the Kirja publishing house in June 1923 for Finnish-language materials and the designation of Finnish as the official language in districts such as Kuivajoki in 1927.[56] Schools increasingly taught in Finnish, fostering a cadre of local administrators, yet this phase subordinated distinct Ingrian dialects and traditions to broader Soviet assimilation goals.[56]Repressions and Deportations

During the forced collectivization campaigns of the late 1920s and early 1930s, Ingrian Finns faced severe repression, including dekulakization and resultant famines that claimed thousands of lives in the region, as agricultural output plummeted and grain requisitions exacerbated starvation.[58] Finnish cultural and religious leaders, viewed as potential nationalist threats, were systematically targeted; by the mid-1930s, most Ingrian Finnish schools had been shuttered, and intelligentsia members were arrested and executed during the Great Purge of 1936–1938, with purges affecting an estimated 40,000 individuals between 1928 and 1938.[58] Deportations intensified in the mid-1930s amid fears of disloyalty near the Finnish border, with major waves in 1929–1931 (approximately 18,000 deported) and 1935–1936 (about 27,000 labeled as kulaks and ethnic risks), sending roughly 50,000 Ingrian Finns overall to Siberia, Kazakhstan, and other remote areas by 1941; mortality during these operations and in exile reached around 25%, or 12,500 deaths, due to harsh transit conditions, disease, and labor camps.[59] These actions, documented in declassified NKVD records referenced in post-Soviet analyses, aimed to dismantle Finnish communal structures and prevent perceived fifth-column activities.[59] After the Soviet reconquest of the region in 1944, over 55,000 Ingrian Finns previously evacuated to Finland were forcibly repatriated, with many subsequently exiled to special settlements in Central Asia and Siberia; combined with wartime deportations of 25,000–30,000 in 1942, this displaced upwards of 90,000, inflicting mortality rates of approximately 20% from starvation, exposure, and forced labor in the immediate postwar years.[59] [58] Archival evidence from these operations highlights the ethnic targeting, as remaining Finnish populations were reclassified and dispersed to avert any resurgence of autonomy.[59]World War II Impacts

The Siege of Leningrad, from 8 September 1941 to 27 January 1944, inflicted catastrophic destruction on central Ingria, as German Army Group North encircled the city and subjected it and adjacent rural districts to relentless artillery shelling and aerial bombing, severing food supplies and causing mass starvation. An estimated 1 million civilians perished in Leningrad from famine, hypothermia, disease, and direct attacks, with daily rations dropping to 125 grams of bread per person by late 1941; the surrounding Ingrian countryside fared similarly, as agricultural output collapsed under blockade conditions and partisan warfare disrupted remaining farms.[60][60] In northern Ingria, Finnish forces advanced during the Continuation War, occupying the Karelian Isthmus and areas up to the Svir River from July 1941 to September 1944, establishing a military administration that prioritized securing ethnic kin while avoiding full integration into German Ostland plans. Civilian impacts included partial evacuations, with Finnish authorities relocating over 60,000 Ingrian Finns—ethnic Lutherans facing Soviet prewar repression—to Finland for protection amid advancing fronts, though some communities endured forced labor and internment under German influence in overlapping zones.[61][62] Wartime devastation extended to demographic shifts, as Soviet NKVD operations deported 25,000–30,000 Ingrian civilians to Siberia in 1942 to prevent collaboration during the siege, exacerbating population losses already strained by combat and exodus. Post-liberation border realignments in 1945 transferred eastern segments of Estonian Ingria, including territories east of Narva and the Pechory district (totaling about 1,000 square kilometers), from the Estonian SSR to the Russian SFSR, consolidating Soviet control over strategic Baltic approaches.[63][64]Post-Soviet Developments

Dissolution of the USSR and Regional Status

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991, the territory historically known as Ingria—encompassing the City of Saint Petersburg and surrounding areas of Leningrad Oblast—transitioned seamlessly into the Russian Federation without gaining autonomous or independent status. Leningrad Oblast, established with its modern borders largely finalized by 1946, retained its administrative structure and name as a federal subject, maintaining continuity from Soviet-era governance. The city of Leningrad, detached as a separate oblast in 1930 but briefly merged during World War II, underwent a referendum on June 12, 1991, where 54.86% of voters with a 65% turnout supported restoring the pre-revolutionary name Saint Petersburg, effective September 6, 1991; the city was designated a federal subject distinct from the oblast, reflecting its strategic and economic prominence but not altering the integrated regional framework.[65] Initial post-Soviet reforms emphasized economic liberalization, including voucher-based privatization starting in 1992 under President Boris Yeltsin's administration, which distributed state assets to citizens but often resulted in concentration among a small elite. In the ports of Saint Petersburg and adjacent areas—key to Ingria's historical trade role via the Gulf of Finland—this process enabled oligarchs to acquire control through auctions and insider deals, as overseen by local officials including then-Deputy Mayor Vladimir Putin, who managed city property sales from 1991 to 1996; by the mid-1990s, entities like the First Freight Company dominated port operations, exemplifying the shift from state monopolies to private oligarchic influence amid corruption allegations.[66][67] Some Ingrian Finns, descendants of pre-war deportees dispersed to Siberia and Central Asia, attempted repatriation to the Leningrad region in the early 1990s, numbering in the low thousands amid relaxed internal migration controls post-perestroika. However, Russia's 1991 citizenship law, which automatically granted citizenship to resident USSR-era populations but required proof of ethnic Russian descent or long-term residency for others, created barriers; many returnees encountered bureaucratic hurdles, residency denials, and limited support, prompting secondary emigration to Finland under its 1990 repatriation policy for Ingrian descendants rather than reintegration into Russia.[68][69]Economic and Social Changes

The transition to a market economy in Ingria after 1991 involved rapid privatization of state assets and a shift away from Soviet-era heavy industry toward services, trade, and port activities centered in St. Petersburg.[70] This restructuring initially caused economic contraction but later supported recovery through revived manufacturing and urban development under local policies emphasizing practical infrastructure over broad liberalization.[71] St. Petersburg's economy became reliant on maritime shipping via its major port, handling over 60 million tons of cargo annually by the 2010s, alongside growing information technology and tourism sectors.[72] Socially, the post-Soviet period saw accelerated emigration among ethnic minorities, particularly Ingrian Finns, whose population declined drastically due to repatriation to Finland facilitated in the 1990s, exacerbating assimilation pressures and cultural erosion in the region.[1] Alcoholism persisted as a major issue, with high consumption rates linked to mortality spikes and social instability, reflecting broader Russian patterns where per capita alcohol intake exceeded 15 liters of pure alcohol annually in the early 2000s before partial declines.[73] Infrastructure investments in the 2010s included the launch of Sapsan high-speed trains on the Moscow-St. Petersburg route in December 2009, cutting travel time to under four hours and boosting connectivity.[74] Western sanctions imposed after 2014 contributed to trade contractions, reducing foreign direct investment and export volumes in sectors like energy and manufacturing, with Russia's overall GDP growth slowing amid estimated annual losses of 2-3% from restricted access to capital and technology.[75] These measures particularly affected St. Petersburg's port-dependent trade, prompting diversification toward Asian markets.[76]Culture and Identity

Language and Dialects

The Ingrian language, spoken by the Izhorians indigenous to the region, belongs to the Finnic branch of the Uralic family and features phonological and lexical traits influenced by neighboring Southern Finnic varieties, including South Estonian, through shared areal developments such as affricate retention and vocabulary overlaps.[77][78] It comprises two primary dialects, Soikkola (northern) and Lower Luga (southern), distinguished by vowel harmony patterns and substrate effects from earlier contacts.[79] Native speakers numbered approximately 120 as of Russia's 2010 census, with most being elderly individuals in rural Leningrad Oblast settlements, reflecting a sharp decline from prior centuries due to Russification policies and urbanization.[80][17] The language's intergenerational transmission has nearly ceased, leaving it with fewer than 200 ethnic adherents actively using it in daily contexts.[81] Russian serves as the overwhelmingly dominant language in modern Ingria, supplanting Finnic varieties through state education and media since the 18th century, though local Russian dialects retain Finnish-origin loanwords—such as terms for household items and agriculture—stemming from historical Ingrian Finnish settlements and bilingualism.[82][83] UNESCO classifies Ingrian as severely endangered in its Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, prompting limited preservation initiatives like archival recordings and dialectological surveys by Finnish and Russian linguists to document remaining fluency before potential extinction.[84][81]Religious Traditions

The indigenous Finnic peoples of Ingria, such as the Votes (Votians) and Izhorians, adhered to animistic and shamanistic traditions centered on nature spirits, ancestor veneration, and ritual practices mediated by shamans before widespread Christianization.[85] These beliefs emphasized a worldview where sacred sites like groves and waters held spiritual significance, with myths of earth-divers and sky gods forming the cosmological framework.[86] Orthodox Christian missions, extending from the Novgorod Republic's influence, began penetrating the region in the 12th and 13th centuries, gradually converting local populations through baptisms and establishment of parishes among the Votes and Izhorians.[17] By the 16th century, these groups had largely adopted Eastern Orthodoxy, integrating pre-Christian elements like folk rituals into church practices, though full adherence solidified amid Russian expansion.[17] The 1617 Treaty of Stolbovo ceded Ingria to Sweden, introducing Lutheranism via Finnish and Swedish settlers who founded the first Finnish-speaking parish in Lembolovo around 1611 under the Church of Sweden.[87] This Scandinavian-influenced confession expanded rapidly, reaching 58 parishes, 36 churches, and 42 chapels by 1655, as Lutheran clergy emphasized scripture, catechism, and congregational hymns among the growing Finnish diaspora.[88] Following Russia's reconquest in 1721 via the Treaty of Nystad, Lutheran communities persisted among Ingrian Finns, maintaining underground worship and ethnic ties despite official Orthodox dominance and conversion incentives.[89] Soviet policies promoting state atheism from the 1920s onward dismantled religious infrastructure, closing nearly all Lutheran churches by 1937 and reducing active adherents to scattered house groups amid broader suppression of confessional life.[87] Adherence plummeted, with formal parishes vanishing except for isolated survivals in remote areas. After 1991, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Ingria revived, registering officially and reconstructing facilities with international aid, drawing on ethnic Finnish roots while attracting some ethnic Russians.[87] By the 2020s, it reported 15,000 baptized members across 119 congregations, reflecting a shift from near-extinction to modest growth centered on bilingual Finnish-Russian services and youth programs.[90] Orthodoxy, meanwhile, retained majority adherence in the broader region, with Lutheranism preserving a distinct minority tradition tied to Ingrian Finnish identity.[91]Folklore and Customs

The folklore of Ingria's indigenous Finnic groups, such as the Izhorians and Votes, centers on oral traditions of runic songs and poetry composed in the Kalevala meter, a syllabic structure shared with other Baltic-Finnic peoples. These include epic narratives akin to those compiled in the Kalevala, with Izhorian epics depicting mythological heroes and creation stories, as preserved in ethnographic recordings from the 19th and 20th centuries. Votic traditions feature wedding songs and laments that interweave personal and communal rites, often performed in dialogic forms between living and deceased kin, reflecting a worldview tied to nature and ancestry.[92][93][94] Customs among Ingrian Finns and related groups integrate pagan animistic beliefs with Christian overlays, as ethnographic studies note the assimilation of pre-Christian spirit worship—such as reverence for forest and water entities—into Orthodox demonology or Lutheran saint veneration. Midsummer festivals, observed as Juhannus by Lutheran Ingrian Finns since their 17th-century settlement, blend solstice bonfires symbolizing fertility and light with communal feasts and herbal rituals, enduring despite Soviet-era suppressions. These practices, rooted in Finnic agrarian cycles, emphasize fire-kindling and wreath-making to ward off malevolent forces, documented in folk song cycles and regional gatherings.[95][23][96] Traditional cuisine draws from Finnish influences and local wetlands, prioritizing rye-based breads fermented for preservation, alongside fish dishes like soups prepared from perch and pike caught in Ingrian lakes and the Gulf of Finland. Dairy ferments and berry preserves complement these staples, supporting seasonal fasting and feast customs tied to Orthodox or Lutheran calendars.[23]Political Movements and Controversies

Historical Autonomy Efforts

In the aftermath of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and amid the ensuing Russian Civil War, Ingrian Finns, facing ethnic marginalization through Russification policies and land expropriations favoring Slavic settlers, pursued territorial self-rule to preserve their cultural and linguistic identity. A nationalist movement in northern Ingria established the Republic of North Ingria (Pohjois-Inkerin tasavalta) on 28 July 1919, declaring independence from Soviet Russia with the aim of eventual unification with Finland. Supported by Finnish volunteers and local militias, the republic briefly controlled territories around Kirjasalo and Pechenga, issuing its own stamps and currency while resisting Red Army advances; however, internal divisions with White Russian allies and superior Bolshevik forces led to its collapse by October 1920, after which approximately 20,000 Ingrian refugees fled to Finland.[3][56] Subsequent efforts for formalized autonomy persisted into the early 1920s, as Finland advocated for Ingrian self-governance during the Tartu Peace Treaty negotiations with Soviet Russia in 1920, proposing either incorporation into Finland or an autonomous status within the RSFSR to address ethnic grievances over forced collectivization and religious suppression of Lutheran communities. Bolshevik authorities rejected these overtures, viewing Ingrian nationalism as a Finnish irredentist threat exacerbated by cross-border kin ties, and instead implemented limited non-territorial cultural concessions through small Ingrian-Finnish national raions in Leningrad Oblast starting in 1926; full Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) proposals, which would have granted broader administrative and linguistic rights akin to those in Karelia, were denied amid centralization drives and fears of separatist revival.[56][97] During World War II, as Finland launched the Continuation War against the USSR in June 1941 to reclaim Winter War losses, Ingrian exiles and locals renewed autonomy bids through military collaboration, forming units like the Ingrian Battalion (Erillinen Pataljoona 6) within the Finnish Army, comprising over 1,000 volunteers who fought Soviet forces in Karelia and Ingria proper. Finnish leadership, pursuing a Greater Finland ideology, implicitly promised post-victory autonomy or reintegration for Ingrian territories—evoking unfulfilled 1919 aspirations—but these commitments evaporated after Finland's 1944 armistice with the USSR, which mandated withdrawal and exposed collaborators to Stalinist reprisals, including mass deportations of up to 30,000 Ingrian Finns to Siberia between 1941 and 1944 for alleged collaboration. The failure to secure self-rule underscored persistent ethnic vulnerabilities, as Soviet authorities prioritized assimilation over concessions.[56][69]Modern Separatism and Independence Claims

The Free Ingria movement, originating in Saint Petersburg in the late 1990s and formalizing in the early 2000s, advocates for the separation of the region—encompassing the city and Leningrad Oblast—from the Russian Federation, positioning it as a pro-Western entity aligned with European values.[98][99] Proponents describe Ingria as a "ready-made European state" with historical ties to Sweden and Finland, proposing it function as a "land bridge" to Baltic neighbors like Estonia and emulate the latter's digital economy model.[99][100] The movement's flag, featuring a blue cross with a red border on a yellow field derived from Swedish heraldry, symbolizes this regional identity distinct from Moscow's "Russian world" narrative.[98] Separatist arguments emphasize Moscow's centralization under Vladimir Putin's "vertical of power" as eroding local autonomy established briefly after the Soviet dissolution, including a 1993 referendum where most voters supported greater regional self-governance.[99] Culturally, activists claim official histories suppress Ingria's European-oriented traditions, alienating a predominantly Russian-speaking population from imperial policies.[99] Economically, Ingria is portrayed as a "donor region" whose resources—sustaining a population of about 7 million—are drained to subsidize less productive areas, hindering development potential.[99] These claims gained renewed urgency after Russia's 2022 mobilization for the Ukraine conflict, which separatists argue imposes senseless burdens on a region ideologically opposed to anti-Western aggression.[98][100] Activities have shifted to online platforms and exile networks, with groups like Ingria Without Borders—led by figures such as Maxim Kuzakhmetov—coordinating from abroad after fleeing post-2022 crackdowns, reducing domestic membership from around 1,000 to roughly 100 activists.[100] Manifestos, such as the Ingria Declaration, outline visions for post-Russian independence amid the federation's anticipated collapse.[99] In summer 2023, the movement formed the "Platoon Free Ingria" volunteer unit within Ukraine's Foreign Legion to advance national revolutions and state-building on Russian ruins.[98] A November 15, 2023, conference in Riga, Latvia, featured dozens of speeches promoting de-imperialization and ties to the "Fourth Baltic Republic" concept, drawing on influences like Estonia's Singing Revolution.[99][98] Within the broader Ingermanland regionalist framework, factions diverge: ethno-nationalists among Ingrian Finns often prioritize cultural autonomy over full secession, while civic regionalists push for outright independence.[98] Small-scale displays, including historical flags at local processions, persist alongside digital manifestos decrying centralization, though overt domestic protests remain limited due to repression.[99]Russian Government Responses and Criticisms

The Russian government has countered perceived separatist threats in Ingria through legal frameworks criminalizing calls for territorial secession, including amendments to federal laws in 2013 that introduced prison terms of up to five years for promoting separatism via public calls or media dissemination.[101] These measures were expanded in 2014 to broaden prohibitions on incitement, targeting activities deemed to undermine the Russian Federation's territorial integrity.[102] In the context of Ingrian movements like Free Ingria, authorities have applied extremism statutes to suppress organizing efforts, with reports of arrests in 2023 linked to attempts by activists to form armed resistance groups against federal control.[98] Official responses emphasize the preservation of national unity as essential to averting instability akin to that in post-Soviet Ukraine, framing regionalist agitation as externally influenced subversion rather than organic grievance. Federal policy integrates Ingria—encompassing Leningrad Oblast and parts of Saint Petersburg—via centralized governance and economic ties, with the region functioning as a net contributor to national revenues rather than a heavy recipient of transfers, underscoring arguments that secession would disrupt interdependent fiscal structures.[103] In June of an unspecified recent year, the Supreme Court banned a purported "Anti-Russian Separatist Movement" as extremist, illustrating proactive judicial measures against loosely defined threats to federation cohesion.[104] Critics, including Human Rights Watch, contend that such countermeasures exacerbate minority erosion by stifling cultural and political expression among Finno-Ugric groups in Ingria, contributing to a broader pattern of repressive laws that silence dissent and fail to address underlying ethnic tensions.[105] Amnesty International has highlighted the misuse of anti-extremism and separatism statutes to prosecute non-violent advocates, arguing these tools disproportionately target regional identities and may foster resentment rather than resolve it, though empirical data on direct radicalization links remains contested amid opaque enforcement.[106] Reports from minority rights monitors note systemic failures in protecting Ingrian Finns and related peoples from discrimination, attributing heightened federal controls to a bias toward Russification over pluralistic federalism.[107]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Ingria

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saint_Petersburg_population_history.svg