Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bowel obstruction

View on Wikipedia

| Bowel obstruction | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Intestinal obstruction, intestinal occlusion |

| |

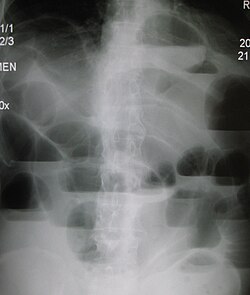

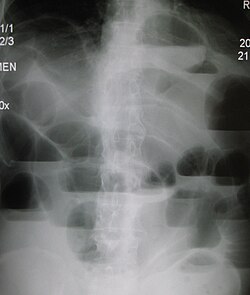

| Upright abdominal X-ray demonstrating a small bowel obstruction. Note multiple air fluid levels. | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, vomiting, bloating, not passing gas[1] |

| Complications | Sepsis, bowel ischemia, bowel perforation[1] |

| Causes | Adhesions, hernias, volvulus, endometriosis, inflammatory bowel disease, appendicitis, tumors, diverticulitis, ischemic bowel, tuberculosis, intussusception[2][1] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging[1] |

| Treatment | Conservative care, surgery[2] |

| Frequency | 3.2 million (2015)<!— incidence —>[3] |

| Deaths | 238,733 (2019)[4] |

Bowel obstruction, also known as intestinal obstruction, is a mechanical or functional obstruction of the intestines that prevents the normal movement of the products of digestion.[2][5] Either the small bowel or large bowel may be affected.[1] Signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, vomiting, bloating and not passing gas.[1] Mechanical obstruction is the cause of about 5 to 15% of cases of severe abdominal pain of sudden onset requiring admission to hospital.[1][2]

Causes of bowel obstruction include adhesions, hernias, volvulus, endometriosis, inflammatory bowel disease, appendicitis, tumors, diverticulitis, ischemic bowel, tuberculosis and intussusception.[1][2] Small bowel obstructions are most often due to adhesions and hernias while large bowel obstructions are most often due to tumors and volvulus.[1][2] The diagnosis may be made on plain X-rays; however, CT scan is more accurate.[1] Ultrasound or MRI may help in the diagnosis of children or pregnant women.[1]

The condition may be treated conservatively or with surgery.[2] Typically intravenous fluids are given, a nasogastric (NG) tube is placed through the nose into the stomach to decompress the intestines, and pain medications are given.[2] Antibiotics are often given.[2] In small bowel obstruction about 25% require surgery.[6] Complications may include sepsis, bowel ischemia and bowel perforation.[1]

About 3.2 million cases of bowel obstruction occurred in 2015, which resulted in 264,000 deaths.[3][7] Both sexes are equally affected and the condition can occur at any age.[6] Bowel obstruction has been documented throughout history, with cases detailed in the Ebers Papyrus of 1550 BC and by Hippocrates.[8]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Depending on the level of obstruction, bowel obstruction can present with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and constipation. Bowel obstruction may be complicated by dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities due to vomiting; respiratory compromise from pressure on the diaphragm by a distended abdomen, or aspiration of vomitus; bowel ischemia or perforation from prolonged distension or pressure from a foreign body and subsequently sepsis due to bowel flora.[9]

In small bowel obstruction, the pain tends to be colicky (cramping and intermittent) in nature, with spasms lasting a few minutes. The pain tends to be central and mid-abdominal. Vomiting may occur before constipation.[9] Common physical exam findings may include signs of dehydration, abdominal distension with tympany, nonspecific abdominal tenderness, and high pitched tinkly bowel sounds.[10]

In large bowel obstruction, the pain is felt lower in the abdomen and the spasms last longer. Common symptoms include abdominal pain, distension, and severe constipation.[11] Constipation occurs earlier and vomiting may be less prominent. Proximal obstruction of the large bowel may present as small bowel obstruction.[9] Patients may notice a history of bloating and narrowing of stools before the onset of more severe symptoms. Symptoms can present quickly in the cases of volvulus and can present over a longer period of time in the setting of cancer. Common physical exam findings may include a palpable hernia, abdominal distension with tympany, nonspecific lower abdominal tenderness, and a rectal mass.[6]

Causes

[edit]Small bowel obstruction

[edit]

Causes of small bowel obstruction include:[2]

- Adhesions from previous abdominal surgery (most common cause)

- Barbed sutures[12]

- Pseudoobstruction

- Hernias containing bowel

- Crohn's disease causing adhesions or inflammatory strictures

- Neoplasms, benign or malignant

- Intussusception

- Volvulus

- Superior mesenteric artery syndrome, a compression of the duodenum by the superior mesenteric artery and the abdominal aorta

- Ischemic strictures

- Foreign bodies (e.g. gallstones in gallstone ileus, swallowed objects such as expandable water toys)

- Intestinal atresia

- Urinary retention

After abdominal surgery, the incidence of small bowel obstruction from any cause is 9%. In those where the cause of the obstruction was clear, adhesions are the single most common cause (more than half).[13]

Large bowel obstruction

[edit]

Causes of large bowel obstruction include:[14]

- Neoplasms / cancer

- Diverticulitis / Diverticulosis

- Hernias

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Colonic volvulus (sigmoid, caecal, transverse colon)

- Adhesions

- Constipation

- Fecal impaction

- Fecaloma

- Colon atresia

- Intestinal pseudoobstruction

- Endometriosis

- Narcotic induced (especially with the large doses given to cancer or palliative care patients)

Outlet obstruction

[edit]Outlet obstruction is a sub-type of large bowel obstruction and refers to conditions affecting the anorectal region that obstruct defecation, specifically conditions of the pelvic floor and anal sphincters. Outlet obstruction can be classified into four groups.[15]

- Functional outlet obstruction

- Inefficient inhibition of the internal anal sphincter

- Short-segment Hirschsprung's disease

- Chagas disease

- Hereditary internal sphincter myopathy

- Inefficient relaxation of the striated pelvic floor muscles

- Anismus (pelvic floor dyssynergia)

- Multiple sclerosis

- Spinal cord lesions

- Inefficient inhibition of the internal anal sphincter

- Mechanical outlet obstruction

- Dissipation of force vector

- Impaired rectal sensitivity

- Megarectum

- Rectal hyposensitivity

Diagnosis

[edit]| Diameter | Assessment |

|---|---|

| <2.5 cm | Non-dilated |

| 2.5-2.9 cm | Mildly dilated |

| 3–4 cm | Moderately dilated |

| >4 cm | Severely dilated |

The main diagnostic tools are blood tests, X-rays of the abdomen, CT scanning, and ultrasound. If a mass is identified, biopsy may determine the nature of the mass.[citation needed]

Radiological signs of bowel obstruction include bowel distension (small bowel loops dilated >3 cm) and the presence of multiple (more than 2) air-fluid levels on supine and erect abdominal radiographs.[18] Ultrasounds may be as useful as CT scanning to make the diagnosis.[19]

Contrast enema or small bowel series or CT scan can be used to define the level of obstruction, whether the obstruction is partial or complete, and to help define the cause of the obstruction. The appearance of water-soluble contrast in the cecum on an abdominal radiograph within 24 hours of it being given by mouth predicts resolution of an adhesive small bowel obstruction with sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 96%.[20]

Colonoscopy, small bowel investigation with ingested camera or push endoscopy, and laparoscopy are other diagnostic options.

-

Small bowel obstruction on ultrasound[21]

-

Small bowel obstruction on ultrasound[21]

-

Small bowel obstruction on ultrasound[21]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Differential diagnoses of bowel obstruction include:

- Ileus

- Pseudo-obstruction or Ogilvie's syndrome

- Intra-abdominal sepsis

- Pneumonia or other systemic illness[22]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment of small and large bowel obstructions are initially similar and non-operative management is usually the initial management strategy as the majority of small bowel obstruction resolve spontaneously with non-operative management.[10][23] Patients are monitored by the surgical team for signs of improvement and resolution of the obstruction on imaging; if the obstruction does not clear then surgical management for the treatment of the causative lesion is required.[24] In malignant large bowel obstruction, endoscopically placed self-expanding metal stents may be used to temporarily relieve the obstruction as a bridge to surgery,[25] or as palliation.[26] Diagnosis of the type of bowel obstruction is normally conducted through initial plain radiograph of the abdomen, luminal contrast studies, computed tomography scan, or ultrasonography prior to determining the best type of treatment.[27]

Further research is needed to find out if parenteral nutrition is of benefit to people with an inoperable blockage of the bowel caused by advanced cancer.[28]

Small bowel obstruction

[edit]In the management of small bowel obstructions, a commonly quoted surgical aphorism is: "never let the sun rise or set on small-bowel obstruction"[29] because about 5.5%[29] of small bowel obstructions are ultimately fatal if treatment is delayed. Improvements in radiological imaging of small bowel obstructions allow for confident distinction between simple obstructions, that can be treated conservatively, and obstructions that are surgical emergencies (volvulus, closed-loop obstructions, ischemic bowel, incarcerated hernias, etc.).[2] Exam findings of bowel compromise requiring immediate surgery include: severe abdominal pain, signs of peritonitis such as rebound tenderness, elevated heart rate, fever, and elevated inflammatory markers on lab work, such as lactic acid.[10][23]

A small flexible tube (nasogastric tube) may be inserted through the nose into the stomach to help decompress the dilated bowel. This tube is uncomfortable but relieves the abdominal cramps, distention, and vomiting. Intravenous therapy is utilized and the urine output may be monitored with a catheter in the bladder.[30][10]

Most people with SBO are initially managed conservatively because in many cases, the bowel will open up. Some adhesions loosen up and the obstruction resolves. The patient is examined several times a day, and X-ray images are made to ensure he or she is not getting clinically worse.[31]

Conservative treatment involves insertion of a nasogastric tube, correction of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities. Opioid pain relievers may be used for patients with severe pain but alternate pain relievers are preferred as opioids can decrease bowel motility.[10]Antiemetics may be administered if the patient is vomiting. Adhesive obstructions often settle without surgery. If the obstruction is complete surgery is usually required.

Most patients improve with conservative care in 2–5 days. When the obstruction is cancer, surgery is the only treatment. Those with bowel resection or lysis of adhesions usually stay in the hospital a few more days until they can eat and walk.[32]

Small bowel obstruction caused by Crohn's disease, peritoneal carcinomatosis, sclerosing peritonitis, radiation enteritis, and postpartum bowel obstruction are typically treated conservatively, i.e. without surgery.

Prognosis

[edit]The prognosis for non-ischemic cases of SBO is good with mortality rates of 3–5%, while prognosis for SBO with ischemia is fair with mortality rates as high as 30%.[33]

Cases of SBO related to cancer are more complicated and require additional intervention to address the malignancy, recurrence, and metastasis, and thus are associated with a more poor prognosis.[22] Surgical options in patients with malignant bowel obstruction need to be considered carefully as while it may provide relief of symptoms in the short term, there is a high risk of mortality and re-obstruction.[34]

All cases of abdominal surgical intervention are associated with increased risk of future small-bowel obstructions. Statistics from U.S. healthcare report 18.1% re-admittance rate within 30 days for patients who undergo SBO surgery.[35] More than 90% of patients also form adhesions after major abdominal surgery.[36] Common consequences of these adhesions include small-bowel obstruction, chronic abdominal pain, pelvic pain, and infertility.[36]

See also

[edit]- Impaction (animals) – Blockage of the intestines

- Neonatal bowel obstruction – A blockage of the intestines in children

- Spastic intestinal obstruction

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gore RM, Silvers RI, Thakrar KH, Wenzke DR, Mehta UK, Newmark GM, et al. (November 2015). "Bowel Obstruction". Radiologic Clinics of North America. 53 (6): 1225–40. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2015.06.008. PMID 26526435.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fitzgerald JE (2010). "Small Bowel Obstruction". Emergency Surgery. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 74–79. doi:10.1002/9781444315172.ch14. ISBN 978-1-4051-7025-3. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ Long D, Mao C, Liu Y, Zhou T, Xu Y, Zhu Y (October 3, 2023). "Global, regional, and national burden of intestinal obstruction from 1990 to 2019: an analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 38 (1): 245. doi:10.1007/s00384-023-04522-6. ISSN 1432-1262. PMID 37787806.

- ^ Adams JG (2012). Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials (Expert Consult -- Online). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-4557-3394-1. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017.

- ^ a b c Ferri FF (2014). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2015: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1093. ISBN 978-0-323-08430-7. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017.

- ^ Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Yeo CJ, McFadden DW, Pemberton JH, Peters JH, Matthews JB (2012). Shackelford's Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1851. ISBN 978-1-4557-3807-6. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Large Bowel Obstruction". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Vercruysse G, Busch R, Dimcheff D, Al-Hawary M, Saad R, Seagull FJ, et al. (2021). Evaluation and Management of Mechanical Small Bowel Obstruction in Adults. Michigan Medicine Clinical Care Guidelines. Ann Arbor (MI): Michigan Medicine University of Michigan. PMID 34314126.

- ^ Ferri F (July 12, 2023). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2024 (1st ed.). Elsevier. pp. 829.e4–829.e6. ISBN 978-0-323-75576-4.

- ^ Segura-Sampedro JJ, Ashrafian H, Navarro-Sánchez A, Jenkins JT, Morales-Conde S, Martínez-Isla A (November 2015). "Small bowel obstruction due to laparoscopic barbed sutures: an unknown complication?". Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas. 107 (11): 677–80. doi:10.17235/reed.2015.3863/2015. hdl:20.500.13003/12378. PMID 26541657.

- ^ ten Broek RP, Issa Y, van Santbrink EJ, Bouvy ND, Kruitwagen RF, Jeekel J, et al. (October 2013). "Burden of adhesions in abdominal and pelvic surgery: systematic review and met-analysis". BMJ. 347 (oct03 1) f5588. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5588. PMC 3789584. PMID 24092941.

- ^ "Intestinal obstruction and Ileus". MedlinePlus. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Zbar AP, Wexner SD (2010). Coloproctology. New York: Springer. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-84882-755-4.

- ^ Jacobs SL, Rozenblit A, Ricci Z, Roberts J, Milikow D, Chernyak V, et al. (April 2007). "Small bowel faeces sign in patients without small bowel obstruction". Clinical Radiology. 62 (4): 353–7. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2006.11.007. PMID 17331829.

- ^ Nguyen H, Loustaunau C, Facista A, Ramsey L, Hassounah N, Taylor H, et al. (July 2010). "Deficient Pms2, ERCC1, Ku86, CcOI in field defects during progression to colon cancer". Journal of Visualized Experiments (41). doi:10.3791/1931. PMC 3149991. PMID 20689513.

- ^ Singh A, Mansouri M (2018), Singh A (ed.), "Imaging of Bowel Obstruction", Emergency Radiology, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 67–75, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-65397-6_5, ISBN 978-3-319-65396-9, retrieved February 19, 2024

- ^ Gottlieb M, Peksa GD, Pandurangadu AV, Nakitende D, Takhar S, Seethala RR (February 2018). "Utilization of ultrasound for the evaluation of small bowel obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 36 (2): 234–242. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.085. PMID 28797559. S2CID 24769945.

- ^ Abbas S, Bissett IP, Parry BR (July 2007). "Oral water soluble contrast for the management of adhesive small bowel obstruction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (3) CD004651. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004651.pub3. PMC 6465054. PMID 17636770.

- ^ a b c "UOTW #20 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. October 1, 2014. Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "Small Bowel Obstruction". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Ferri F (July 12, 2023). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2024 (1st ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-75576-4.

- ^ Bower KL, Lollar DI, Williams SL, Adkins FC, Luyimbazi DT, Bower CE (October 1, 2018). "Small Bowel Obstruction". Surgical Clinics of North America. Emergency General Surgery. 98 (5): 945–971. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2018.05.007. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 30243455. S2CID 265759123.

- ^ Young CJ, Suen MK, Young J, Solomon MJ (October 2011). "Stenting large bowel obstruction avoids a stoma: consecutive series of 100 patients". Colorectal Disease. 13 (10): 1138–41. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02432.x. PMID 20874797. S2CID 12724976.

- ^ Mosler P, Mergener KD, Brandabur JJ, Schembre DB, Kozarek RA (February 2005). "Palliation of gastric outlet obstruction and proximal small bowel obstruction with self-expandable metal stents: a single center series". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 39 (2): 124–8. PMID 15681907.

- ^ Holzheimer RG (2001). Surgical Treatment. NCBI Bookshelf. ISBN 3-88603-714-2. Archived from the original on August 27, 2011.

- ^ Sowerbutts AM, Lal S, Sremanakova J, Clamp A, Todd C, Jayson GC, et al. (August 2018). "Home parenteral nutrition for people with inoperable malignant bowel obstruction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8) CD012812. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012812.pub2. PMC 6513201. PMID 30095168.

- ^ a b Maglinte DD, Kelvin FM, Rowe MG, Bender GN, Rouch DM (January 2001). "Small-bowel obstruction: optimizing radiologic investigation and nonsurgical management". Radiology. 218 (1): 39–46. doi:10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja5439. PMID 11152777. Archived from the original on April 18, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- ^ Small Bowel Obstruction overview Archived February 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Small Bowel Obstruction: Treating Bowel Adhesions Non-Surgically Archived February 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Clear Passage treatment center online portal Retrieved February 19, 2010

- ^ Small Bowel Obstruction Archived July 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. February 19, 2010

- ^ Kakoza R, Lieberman G (May 2006). Mechanical Small Bowel Obstruction (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ Song Y, Metzger DA, Bruce AN, Krouse RS, Roses RE, Fraker DL, et al. (January 2022). "Surgical Outcomes in Patients With Malignant Small Bowel Obstruction: A National Cohort Study". Annals of Surgery. 275 (1): e198 – e205. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003890. ISSN 0003-4932. PMID 32209901. S2CID 214643950.

- ^ "Readmissions to U.S. Hospitals by Procedure" (PDF). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ a b Liakakos T, Thomakos N, Fine PM, Dervenis C, Young RL (2001). "Peritoneal adhesions: etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical significance. Recent advances in prevention and management". Digestive Surgery. 18 (4): 260–73. doi:10.1159/000050149. PMID 11528133. S2CID 30816909.

![Small bowel obstruction on ultrasound[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e5/UOTW_20_-_Ultrasound_of_the_Week_3.jpg/120px-UOTW_20_-_Ultrasound_of_the_Week_3.jpg)