Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Irregular moon

View on WikipediaIn astronomy, an irregular moon, irregular satellite, or irregular natural satellite is a natural satellite following an orbit that is irregular in some of the following ways: Distant; inclined; highly elliptical; retrograde. They have often been captured by their parent planet, unlike regular satellites formed in orbit around them. Irregular moons have a stable orbit, unlike temporary satellites which often have similarly irregular orbits but will eventually depart. The term does not refer to shape; Triton, for example, is a round moon but is considered irregular due to its orbit and origins.

As of April 2025[update], 358 irregular moons are known, orbiting all four of the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune). The largest of each planet are Himalia of Jupiter, Phoebe of Saturn, Sycorax of Uranus, and Triton of Neptune. Triton is rather unusual for an irregular moon; if it is excluded, then Nereid is the largest irregular moon around Neptune. It is currently thought that the irregular satellites were once independent objects orbiting the Sun before being captured by a nearby planet, early in the history of the Solar System. An alternative suggests that they originated further out in the Kuiper belt[1] and were captured after the close flyby of another star.[2]

Definition

[edit]| Planet | Hill radius rH (106 km)[3] |

rH (°)[3] | Number known | Farthest known satellite (106 km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jupiter | 51 | 4.7 | 89 | 24.2 (0.47rH) |

| Saturn | 69 | 3.0 | 250 | 28.0 (0.41rH) |

| Uranus | 73 | 1.5 | 10 | 20.4 (0.28rH) |

| Neptune | 116 | 1.5 | 9 (including Triton) | 50.7 (0.44rH) |

There is no widely accepted precise definition of an irregular satellite. Informally, satellites are considered irregular if they are far enough from the planet that the precession of their orbital plane is primarily controlled by the Sun, other planets, or other moons.[4]

In practice, the satellite's semi-major axis is compared with the radius of the planet's Hill sphere (that is, the sphere of its gravitational influence), . Irregular satellites have semi-major axes greater than 0.05 with apoapses extending as far as to 0.65 .[3] The radius of the Hill sphere is given in the adjacent table: Uranus and Neptune have larger Hill sphere radii than Jupiter and Saturn, despite being less massive, because they are farther from the Sun. However, no known irregular satellite has a semi-major axis exceeding 0.47 .[5]

Earth's Moon seems to be an exception: it is not usually listed as an irregular satellite even though its precession is primarily controlled by the Sun[citation needed] and its semi-major axis is greater than 0.05 of the radius of Earth's Hill sphere. On the other hand, Neptune's Triton, which is probably a captured object, is usually listed as irregular despite being within 0.05 of the radius of Neptune's Hill sphere, so that Triton's precession is primarily controlled by Neptune's oblateness instead of by the Sun.[5] Neptune's Nereid and Saturn's Iapetus have semi-major axes close to 0.05 of the radius of their parent planets' Hill spheres: Nereid (with a very eccentric orbit) is usually listed as irregular, but not Iapetus.

Orbits

[edit]Current distribution

[edit]

The orbits of the known irregular satellites are extremely diverse, but there are certain patterns. Retrograde orbits are far more common (83%) than prograde orbits. No satellites are known with orbital inclinations higher than 60° (or smaller than 130° for retrograde satellites); moreover, apart from Nereid, no irregular moon has inclination less than 26°, and inclinations greater than 170° are only found in Saturn's system. In addition, some groupings can be identified, in which one large satellite shares a similar orbit with a few smaller ones.[5]

Given their distance from the planet, the orbits of the outer satellites are highly perturbed by the Sun and their orbital elements change widely over short intervals. The semi-major axis of Pasiphae, for example, changes as much as 1.5 Gm in two years (single orbit), the inclination around 10°, and the eccentricity as much as 0.4 in 24 years (twice Jupiter's orbit period).[6] Consequently, mean orbital elements (averaged over time) are used to identify the groupings rather than osculating elements at the given date. (Similarly, the proper orbital elements are used to determine the families of asteroids.)

Origin

[edit]Irregular satellites may have been captured from heliocentric orbits. (Indeed, it appears that the irregular moons of the giant planets, the Jovian and Neptunian trojans, and grey Kuiper belt objects have a similar origin.[7]). Alternatively, trans-Neptunian objects may have been injected due to the close passing star and a fraction of these injected TNOs captured by the giant planets.[8] For this to occur, at least one of three things needs to have happened:

- energy dissipation (e.g. in interaction with the primordial gas cloud)

- a substantial (40%) extension of the planet's Hill sphere in a brief period of time (thousands of years)

- a transfer of energy in a three-body interaction. This could involve:

- a collision (or close encounter) of an incoming body and a satellite, resulting in the incoming body losing energy and being captured.

- a close encounter between an incoming binary object and the planet (or possibly an existing moon), resulting in one component of the binary being captured. Such a route has been suggested as most likely for Triton.[9]

After the capture, some of the satellites could break up leading to groupings of smaller moons following similar orbits. Resonances could further modify the orbits making these groupings less recognizable.

Long-term stability

[edit]The current orbits of the irregular moons are stable, in spite of substantial perturbations near the apocenter.[10] The cause of this stability in a number of irregulars is the fact that they orbit with a secular or Kozai resonance.[11]

In addition, simulations indicate the following conclusions:

- Orbits with inclinations between 50° and 130° are very unstable: their eccentricity increases quickly resulting in the satellite being lost[6]

- Retrograde orbits are more stable than prograde (stable retrograde orbits can be found further from the planet)

Increasing eccentricity results in smaller pericenters and large apocenters. The satellites enter the zone of the regular (larger) moons and are lost or ejected via collision and close encounters. Alternatively, the increasing perturbations by the Sun at the growing apocenters push them beyond the Hill sphere.

Retrograde satellites can be found further from the planet than prograde ones. Detailed numerical integrations have shown this asymmetry. The limits are a complicated function of the inclination and eccentricity, but in general, prograde orbits with semi-major axes up to 0.47 rH (Hill sphere radius) can be stable, whereas for retrograde orbits stability can extend out to 0.67 rH.

The boundary for the semimajor axis is surprisingly sharp for the prograde satellites. A satellite on a prograde, circular orbit (inclination=0°) placed at 0.5 rH would leave Jupiter in as little as forty years. The effect can be explained by so-called evection resonance. The apocenter of the satellite, where the planet's grip on the moon is at its weakest, gets locked in resonance with the position of the Sun. The effects of the perturbation accumulate at each passage pushing the satellite even further outwards.[10]

The asymmetry between the prograde and retrograde satellites can be explained very intuitively by the Coriolis acceleration in the frame rotating with the planet. For the prograde satellites the acceleration points outward and for the retrograde it points inward, stabilising the satellite.[12]

Temporary captures

[edit]The capture of an asteroid from a heliocentric orbit is not always permanent. According to simulations, temporary satellites should be a common phenomenon.[13][14] The only observed examples are 2006 RH120 and 2020 CD3, which were temporary satellites of Earth discovered in 2006 and 2020, respectively.[15][16][17]

Physical characteristics

[edit]This graph was using the legacy Graph extension, which is no longer supported. It needs to be converted to the new Chart extension. |

Size

[edit]

Because objects of a given size are more difficult to see the greater their distance from Earth, the known irregular satellites of Uranus and Neptune are larger than those of Jupiter and Saturn; smaller ones probably exist but have not yet been observed. Bearing this observational bias in mind, the size distribution of irregular satellites appears to be similar for all four giant planets.

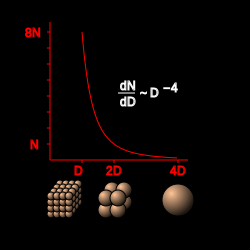

The size distribution of asteroids and many similar populations can be expressed as a power law: there are many more small objects than large ones, and the smaller the size, the more numerous the object. The mathematical relation expressing the number of objects, , with a diameter smaller than a particular size, , is approximated as:

- with q defining the slope.

The value of q is determined through observation.

For irregular moons, a shallow power law (q ≃ 2) is observed for sizes of 10 to 100 km,† but a steeper law (q ≃ 3.5) is observed for objects smaller than 10 km. An analysis of images taken by the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope in 2010 shows that the power law for Jupiter's population of small retrograde satellites, down to a detection limit of ≈ 400 m, is relatively shallow, at q ≃ 2.5. Thus it can be extrapolated that Jupiter should have 600+600

−300 moons 400 m in diameter or greater.[18]

For comparison, the distribution of large Kuiper belt objects is much steeper (q ≈ 4). That is, for every object of 1000 km there are a thousand objects with a diameter of 100 km, though it's unknown how far this distribution extends. The size distribution of a population may provide insights into its origin, whether through capture, collision and break-up, or accretion.

†For every object of 100 km, ten objects of 10 km can be found.

Around each giant planet, there is one irregular satellite that dominates, by having over three-quarters the mass of the entire irregular satellite system: Jupiter's Himalia (about 75%), Saturn's Phoebe (about 98%), Uranus's Sycorax (about 90%), and Neptune's Nereid (about 98%). Nereid also dominates among irregular satellites taken altogether, having about two-thirds the mass of all irregular moons combined. Phoebe makes up about 17%, Sycorax about 7%, and Himalia about 5%: the remaining moons add up to about 4%. (In this discussion, Triton is not included.)[5]

Colours

[edit]

The colours of irregular satellites can be studied via colour indices: simple measures of differences of the apparent magnitude of an object through blue (B), visible i.e. green-yellow (V), and red (R) filters. The observed colours of the irregular satellites vary from neutral (greyish) to reddish (but not as red as the colours of some Kuiper belt objects).

| albedo[19] | neutral | reddish | red |

|---|---|---|---|

| low | C 3–8% | P 2–6% | D 2–5% |

| medium | M 10–18% | A 13–35% | |

| high | E 25–60% |

Each planet's system displays slightly different characteristics. Jupiter's irregulars are grey to slightly red, consistent with C, P and D-type asteroids.[20] Some groups of satellites are observed to display similar colours (see later sections). Saturn's irregulars are slightly redder than those of Jupiter.

The large Uranian irregular satellites (Sycorax and Caliban) are light red, whereas the smaller Prospero and Setebos are grey, as are the Neptunian satellites Nereid and Halimede.[21]

Spectra

[edit]With the current resolution, the visible and near-infrared spectra of most satellites appear featureless. So far, water ice has been inferred on Phoebe and Nereid and features attributed to aqueous alteration were found on Himalia.[citation needed]

Rotation

[edit]Regular satellites are usually tidally locked (that is, their orbit is synchronous with their rotation so that they only show one face toward their parent planet). In contrast, tidal forces on the irregular satellites are negligible given their distance from the planet, and rotation periods in the range of only ten hours have been measured for the biggest moons Himalia, Phoebe, Sycorax, and Nereid (to compare with their orbital periods of hundreds of days). Such rotation rates are in the same range that is typical for asteroids.[citation needed] Triton, being much larger and closer to its parent planet, is tidally locked.

Families with a common origin

[edit]Some irregular satellites appear to orbit in 'groups', in which several satellites share similar orbits. The leading hypothesis is that these objects constitute collisional families, parts of a larger body that broke up.

Dynamic groupings

[edit]Simple collision models can be used to estimate the possible dispersion of the orbital parameters given a velocity impulse Δv. Applying these models to the known orbital parameters makes it possible to estimate the Δv necessary to create the observed dispersion. A Δv of tens of meters per seconds (5–50 m/s) could result from a break-up. Dynamical groupings of irregular satellites can be identified using these criteria and the likelihood of the common origin from a break-up evaluated.[22]

When the dispersion of the orbits is too wide (i.e. it would require Δv in the order of hundreds of m/s):

- either more than one collision must be assumed, i.e. the cluster should be further subdivided into groups

- or significant post-collision changes, for example resulting from resonances, must be postulated.

Colour groupings

[edit]When the colours and spectra of the satellites are known, the homogeneity of these data for all the members of a given grouping is a substantial argument for a common origin. However, lack of precision in the available data often makes it difficult to draw statistically significant conclusions. In addition, the observed colours are not necessarily representative of the bulk composition of the satellite.

Observed groupings

[edit]Irregular satellites of Jupiter

[edit]

Typically, the following groupings are listed (dynamically tight groups displaying homogenous colours are listed in bold)

- Prograde satellites

- The Himalia group shares an average inclination of 28°. They are confined dynamically (Δv ≈ 150 m/s). They are homogenous at visible wavelengths (having neutral colours similar to those of C-type asteroids) and at near infrared wavelengths[23]

- The prograde satellites Themisto and Valetudo are not part of any known group.

Jupiter · Himalia · Callisto

- Retrograde satellites

- The Carme group shares an average inclination of 165°. It is dynamically tight (5 < Δv < 50 m/s). It is very homogenous in colour, each member displaying light red colouring consistent with a D-type asteroid progenitor.

- The Ananke group shares an average inclination of 148°. It shows little dispersion of orbital parameters (15 < Δv < 80 m/s). Ananke itself appears light red but the other group members are grey.

- The Pasiphae group is very dispersed. Pasiphae itself appears to be grey, whereas other members (Callirrhoe, Megaclite) are light red.

Sinope, sometimes included into the Pasiphae group, is red and given the difference in inclination, it could be captured independently.[20][24] Pasiphae and Sinope are also trapped in secular resonances with Jupiter.[10][22]

Irregular satellites of Saturn

[edit]

The following groupings are commonly listed for Saturn's satellites:

- Prograde satellites

- The Gallic group shares an average inclination of 34°. Their orbits are dynamically tight (Δv ≈ 50 m/s), and they are light red in colour; the colouring is homogenous at both visible and near infra-red wavelengths.[23]

- The Inuit group shares an average inclination of 46°. Their orbits are widely dispersed (Δv ≈ 350 m/s) but they are physically homogenous, sharing a light red colouring.

- Retrograde satellites

- The Norse group is defined mostly for naming purposes; the orbital parameters are very widely dispersed. Sub-divisions have been investigated, including

-

Animation of Phoebe's orbit.

Saturn · Phoebe · Titan

Irregular satellites of Uranus and Neptune

[edit]

| Planet | rmin[3] |

|---|---|

| Jupiter | 1.5 km |

| Saturn | 3 km |

| Uranus | 7 km |

| Neptune | 16 km |

According to current knowledge, the number of irregular satellites orbiting Uranus and Neptune is smaller than that of Jupiter and Saturn. However, it is thought that this is simply a result of observational difficulties due to the greater distance of Uranus and Neptune. The table at right shows the minimum radius (rmin) of satellites that can be detected with current technology, assuming an albedo of 0.04; thus, there are almost certainly small Uranian and Neptunian moons that cannot yet be seen.

Due to the smaller numbers, statistically significant conclusions about the groupings are difficult. A single origin for the retrograde irregulars of Uranus seems unlikely given a dispersion of the orbital parameters that would require high impulse (Δv ≈ 300 km), implying a large diameter of the impactor (395 km), which is incompatible in turn with the size distribution of the fragments. Instead, the existence of two groupings has been speculated:[20]

These two groups are distinct (with 3σ confidence) in their distance from Uranus and in their eccentricity.[25] However, these groupings are not directly supported by the observed colours: Caliban and Sycorax appear light red, whereas the smaller moons are grey.[21]

For Neptune, a possible common origin of Psamathe and Neso has been noted.[26] Given the similar (grey) colours, it was also suggested that Halimede could be a fragment of Nereid.[21] The two satellites have had a very high probability (41%) of collision over the age of the solar system.[27]

Exploration

[edit]

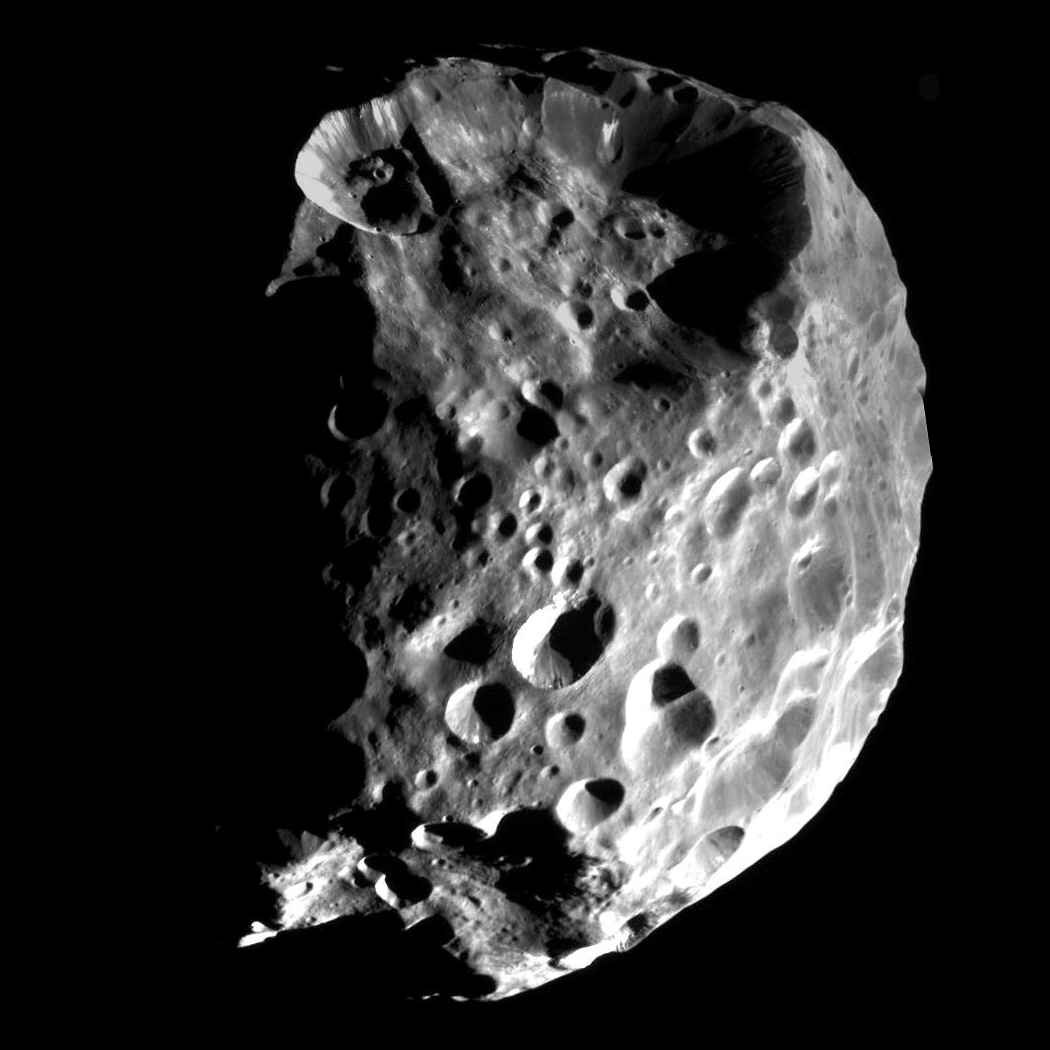

To date, the only irregular satellites to have been visited close-up by a spacecraft are Triton and Phoebe, the largest of Neptune's and Saturn's irregulars respectively. Triton was imaged by Voyager 2 in 1989 and Phoebe by the Cassini probe in 2004. Voyager 2 also captured a distant image of Neptune's Nereid in 1989, and Cassini captured a distant, low-resolution image of Jupiter's Himalia in 2000. New Horizons captured low-resolution images of Jupiter's Himalia, Elara, and Callirrhoe in 2007. Throughout the Cassini mission, many Saturnian irregulars were observed from a distance: Albiorix, Bebhionn, Bergelmir, Bestla, Erriapus, Fornjot, Greip, Hati, Hyrrokkin, Ijiraq, Kari, Kiviuq, Loge, Mundilfari, Narvi, Paaliaq, Siarnaq, Skathi, Skoll, Suttungr, Tarqeq, Tarvos, Thrymr, and Ymir.[5]

The Tianwen-4 mission (to launch 2029) is planned to focus on the regular moon Callisto around Jupiter, but it may fly-by several irregular Jovian satellites before settling into Callistonian orbit.[28]

Gallery

[edit]-

71 irregular moons of Jupiter (with Callisto for comparison; the other Galileans are also visible near the centre, though not labelled explicitly). Data as of 2021.

-

122 irregular moons of Saturn (with Titan, Hyperion, and Iapetus for comparison). Data as of 2023.

-

9 irregular moons of Uranus. Data as of 2021.

-

6 irregular moons of Neptune (excluding Triton). Data as of 2021.

References

[edit]- ^ Pfalzner, Susanne; Govind, Amith; Wagner, Frank W. (2024-09-01). "Irregular Moons Possibly Injected from the Outer Solar System by a Stellar Flyby". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 972 (2): L21. arXiv:2409.03529. Bibcode:2024ApJ...972L..21P. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ad63a6. ISSN 2041-8205.

- ^ Pfalzner, Susanne; Govind, Amith; Portegies Zwart, Simon (2024-09-04). "Trajectory of the stellar flyby that shaped the outer Solar System". Nature Astronomy. 8 (11): 1380–1386. arXiv:2409.03342. Bibcode:2024NatAs...8.1380P. doi:10.1038/s41550-024-02349-x. ISSN 2397-3366.

- ^ a b c d Sheppard, S. S. (2006). "Outer irregular satellites of the planets and their relationship with asteroids, comets and Kuiper Belt objects". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 1: 319–334. arXiv:astro-ph/0605041. Bibcode:2006IAUS..229..319S. doi:10.1017/S1743921305006824. S2CID 2077114.

- ^ "Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Denk, Tilmann (2024). "Outer Moons of Saturn". tilmanndenk.de. Tilmann Denk. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ a b Carruba, V.; Burns, Joseph A.; Nicholson, Philip D.; Gladman, Brett J. (2002). "On the Inclination Distribution of the Jovian Irregular Satellites" (PDF). Icarus. 158 (2): 434–449. Bibcode:2002Icar..158..434C. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6896. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ Sheppard, S. S.; Trujillo, C. A. (2006). "A Thick Cloud of Neptune Trojans and Their Colors". Science. 313 (5786): 511–514. Bibcode:2006Sci...313..511S. doi:10.1126/science.1127173. PMID 16778021. S2CID 35721399.

- ^ Pfalzner, Susanne; Govind, Amith; Wagner, Frank W. (September 2024). "Irregular Moons Possibly Injected from the Outer Solar System by a Stellar Flyby". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 972 (2): L21. arXiv:2409.03529. Bibcode:2024ApJ...972L..21P. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ad63a6. ISSN 2041-8205.

- ^ Agnor, C. B. and Hamilton, D. P. (2006). "Neptune's capture of its moon Triton in a binary-planet gravitational encounter". Nature. 441 (7090): 192–4. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..192A. doi:10.1038/nature04792. PMID 16688170. S2CID 4420518.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Nesvorný, David; Alvarellos, Jose L. A.; Dones, Luke; Levison, Harold F. (2003). "Orbital and Collisional Evolution of the Irregular Satellites" (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 126 (1): 398. Bibcode:2003AJ....126..398N. doi:10.1086/375461. S2CID 8502734. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-04-15. Retrieved 2006-07-29.

- ^ Ćuk, Matija; Burns, Joseph A. (2004). "On the Secular Behavior of Irregular Satellites". The Astronomical Journal. 128 (5): 2518–2541. arXiv:astro-ph/0408119. Bibcode:2004AJ....128.2518C. doi:10.1086/424937. S2CID 18564122.

- ^ Hamilton, Douglas P.; Burns, Joseph A. (1991). "Orbital stability zones about asteroids". Icarus. 92 (1): 118–131. Bibcode:1991Icar...92..118H. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(91)90039-V.

- ^ Camille M. Carlisle (December 30, 2011). "Pseudo-moons Orbit Earth". Sky & Telescope.

- ^ Fedorets, Grigori; Granvik, Mikael; Jedicke, Robert (March 15, 2017). "Orbit and size distributions for asteroids temporarily captured by the Earth-Moon system". Icarus. 285: 83–94. Bibcode:2017Icar..285...83F. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.12.022.

- ^ "2006 RH120 ( = 6R10DB9) (A second moon for the Earth?)". Great Shefford Observatory. September 14, 2017. Archived from the original on 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2017-11-13.

- ^ Roger W. Sinnott (April 17, 2007). "Earth's "Other Moon"". Sky & Telescope. Archived from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2017-11-13.

- ^ "MPEC 2020-D104 : 2020 CD3: Temporarily Captured Object". Minor Planet Electronic Circular. Minor Planet Center. 25 February 2020. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Ashton, Edward; Beaudoin, Matthew; Gladman, Brett (September 2020). "The Population of Kilometer-scale Retrograde Jovian Irregular Moons". The Planetary Science Journal. 1 (2): 52. arXiv:2009.03382. Bibcode:2020PSJ.....1...52A. doi:10.3847/PSJ/abad95. S2CID 221534456.

- ^ Based on the definitions from Oxford Dictionary of Astronomy, ISBN 0-19-211596-0

- ^ a b c Grav, Tommy; Holman, Matthew J.; Gladman, Brett J.; Aksnes, Kaare (2003). "Photometric survey of the irregular satellites". Icarus. 166 (1): 33–45. arXiv:astro-ph/0301016. Bibcode:2003Icar..166...33G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2003.07.005. S2CID 7793999.

- ^ a b c Grav, Tommy; Holman, Matthew J.; Fraser, Wesley C. (2004-09-20). "Photometry of Irregular Satellites of Uranus and Neptune". The Astrophysical Journal. 613 (1): L77 – L80. arXiv:astro-ph/0405605. Bibcode:2004ApJ...613L..77G. doi:10.1086/424997. S2CID 15706906.

- ^ a b Nesvorn, David; Beaug, Cristian; Dones, Luke (2004). "Collisional Origin of Families of Irregular Satellites" (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 127 (3): 1768–1783. Bibcode:2004AJ....127.1768N. doi:10.1086/382099. S2CID 27293848. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- ^ a b Grav, Tommy; Holman, Matthew J. (2004). "Near-Infrared Photometry of the Irregular Satellites of Jupiter and Saturn". The Astrophysical Journal. 605 (2): L141 – L144. arXiv:astro-ph/0312571. Bibcode:2004ApJ...605L.141G. doi:10.1086/420881. S2CID 15665146.

- ^ Sheppard, S. S.; Jewitt, D. C. (2003). "An abundant population of small irregular satellites around Jupiter" (PDF). Nature. 423 (6937): 261–263. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..261S. doi:10.1038/nature01584. PMID 12748634. S2CID 4424447. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-15. Retrieved 2015-08-29.

- ^ Sheppard, S. S.; Jewitt, D.; Kleyna, J. (2005). "An Ultradeep Survey for Irregular Satellites of Uranus: Limits to Completeness". The Astronomical Journal. 129 (1): 518–525. arXiv:astro-ph/0410059. Bibcode:2005AJ....129..518S. doi:10.1086/426329. S2CID 18688556.

- ^ Sheppard, Scott S.; Jewitt, David C.; Kleyna, Jan (2006). "A Survey for "Normal" Irregular Satellites around Neptune: Limits to Completeness". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (1): 171–176. arXiv:astro-ph/0604552. Bibcode:2006AJ....132..171S. doi:10.1086/504799. S2CID 154011.

- ^ Holman, M. J.; Kavelaars, J. J.; Grav, T.; et al. (2004). "Discovery of five irregular moons of Neptune" (PDF). Nature. 430 (7002): 865–867. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..865H. doi:10.1038/nature02832. PMID 15318214. S2CID 4412380. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Andrew Jones (2023-12-21). "China's plans for outer Solar System exploration". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2023-12-27.

External links

[edit]- David Jewitt's pages

- Discovery circumstances from JPL

- Mean orbital elements from JPL

- MPC: Natural Satellites Ephemeris Service

- Tilmann Denk: Outer Moons of Jupiter and Saturn

Irregular moon

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Classification

Definition

Irregular moons, also referred to as irregular satellites, are natural satellites of planets characterized by distant orbits that exhibit high eccentricity (typically e > 0.1), high inclination relative to the planet's equatorial plane (usually i > 30°), and often retrograde motion, with semi-major axes generally exceeding 50 planetary radii.[9] These orbital traits distinguish them as likely captured objects from the early solar system, rather than bodies formed in situ around their host planet.[9] The term "irregular satellite" is the standard astronomical designation, emphasizing their non-native origins, while "irregular moon" serves as a more accessible synonym in general discourse; naming conventions for these bodies, particularly Jupiter's, frequently invoke figures from Greek and Roman mythology associated with Zeus or Jupiter, such as lovers or descendants.[10] Archetypal examples of irregular moons include Phoebe, Saturn's largest outer satellite with a retrograde orbit at about 12 million km from the planet, Sycorax, Uranus's outermost known moon exhibiting a highly inclined and eccentric path, and Nereid, Neptune's distant satellite known for its extreme eccentricity of nearly 0.75.[11] These exemplars highlight the class's defining features of remoteness and dynamical irregularity, often placing them far beyond the planet's regular satellite systems.[11] As of November 2025, approximately 358 confirmed irregular moons are documented orbiting the outer planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, reflecting ongoing discoveries through advanced telescopic surveys.[12]Distinction from Regular Moons

Irregular moons, also known as irregular satellites, are fundamentally distinguished from regular moons by their orbital characteristics and origins. Regular moons typically occupy prograde, low-inclination, nearly circular orbits close to their parent planet, often within a few planetary radii, as they form through the accretion of material in a circumplanetary disk surrounding the planet during its formation.[13] In contrast, irregular moons follow highly eccentric, inclined, and often retrograde paths at greater distances, extending up to half the planet's Hill sphere radius, reflecting their capture from external heliocentric orbits rather than in situ formation.[9] These orbital disparities arise because irregular moons were not born alongside their host planets but were dynamically acquired later, leading to non-coplanar and non-circular trajectories that deviate significantly from the equatorial plane of the planet. The formation mechanisms further underscore this divide. Regular moons assemble via gradual accretion in the dense environment of a protoplanetary disk, resulting in larger, more spherical bodies aligned with the planet's spin axis.[13] Irregular moons, however, originate from capture processes, such as three-body gravitational interactions or temporary gas drag during planetary encounters, often facilitated by the dynamical instabilities in the early Solar System.[9] For instance, models like the Nice model suggest that planetary migration among the giant planets scattered planetesimals, enabling efficient capture of irregular moons through exchange reactions or close encounters, which circularized some orbits over time but preserved their overall eccentricity and inclination.[14] This capture paradigm explains why irregular moons are generally smaller and irregularly shaped, as they represent primordial Kuiper Belt or scattered disk objects rather than disk-grown satellites.[15] Observationally, these differences pose significant challenges for detecting irregular moons. Their distant, eccentric orbits make them faint and slow-moving against the stellar background, requiring deep imaging surveys with large telescopes to identify them, unlike the brighter, closer regular moons that were discovered early through visual or photographic means.[15] For example, Jupiter's four large regular Galilean moons were observed in 1610 by Galileo Galilei, while the first irregular moon, Himalia, was not found until 1904 due to its dimness and remoteness.[9] This historical bias means regular moons dominated initial catalogs, but modern surveys have revealed their underrepresentation in sheer numbers. Statistically, irregular moons comprise the vast majority of known satellites around the outer planets, accounting for approximately 86% of the total for Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune combined, with 358 confirmed as of November 2025, though regular moons remain larger and more prominent in terms of mass and brightness.[12] This imbalance highlights the capture efficiency during early Solar System chaos, where numerous small bodies were ensnared, while only a handful of regular moons accreted per planet.[13]Orbital Properties

General Characteristics

Irregular moons are characterized by highly eccentric and inclined orbits that distinguish them from the more circular and equatorial regular satellites. Their semi-major axes typically range from about 50 to 1000 planetary radii, placing them far beyond the denser inner satellite systems and exposing them to significant solar perturbations.[9] The average eccentricities fall in the range of approximately 0.2 to 0.5, with prograde irregular moons showing somewhat lower values (0.1–0.3) compared to retrograde ones (0.2–0.5), resulting in elongated paths that bring them closer to the planet at periapsis and farther at apoapsis. Inclinations relative to the planet's equatorial plane are generally high, with prograde orbits spanning 20°–50° and retrograde orbits from 90°–180°, though orbits between 50° and 130° are dynamically unstable due to eccentricity growth from resonances.[16] Retrograde orbits predominate among irregular moons across the giant planets (e.g., overall approximately 20% prograde versus 80% retrograde as of 2025), reflecting greater long-term stability for retrograde examples.[17] Retrograde orbits prove more stable against perturbations, particularly at larger semi-major axes, because the corotation of the satellite with the perturbing body (such as the Sun) reduces disruptive effects compared to prograde cases, where evection resonance can destabilize distant orbits. A notable feature of irregular moon orbits is their tendency to cluster in specific planes, with the normals to their orbital planes aligning closely with the normal to the Solar System's invariable plane—the plane defined by the total angular momentum of the planets. This alignment arises from the dynamics of capture, as the moons were likely drawn from a heliocentric planetesimal disk coplanar with the early Solar System's invariable plane, leading to post-capture inclinations that preserve this orientation despite subsequent evolution.[16] Capture into these bound orbits requires energy dissipation during three-body interactions, such as planetary encounters or gas drag, to reduce the relative velocity sufficiently for retention. Following capture, the orbital energy of an irregular moon in the two-body approximation with its host planet is given by where is the gravitational constant, and are the masses of the planet and moon, respectively, and is the semi-major axis; this negative energy confirms the bound state essential for long-term retention.[9]Current Distribution

As of November 2025, irregular moons are distributed among the four giant planets of the outer Solar System, with a total of approximately 358 known objects. Saturn hosts the largest population at 250, followed by Jupiter with 89, while Uranus and Neptune have smaller known retinues of 10 and 9, respectively (including Triton for Neptune, which exhibits characteristics of a captured body). These counts reflect ongoing surveys using large ground-based telescopes, with Saturn's dominance stemming from extensive recent observations, including the discovery of 128 new retrograde irregular moons in March 2025.[18][3][19] The orbital ranges of these irregular moons, characterized by their large semi-major axes, vary by host planet due to differences in planetary mass and Hill sphere extents. For Jupiter, semi-major axes span 11 to 50 million km; for Saturn, 20 to 60 million km; for Uranus, 3 to 12 million km; and for Neptune, 5 to 50 million km. These distant orbits place the moons well beyond the regular satellite systems, often approaching the limits of gravitational stability within each planet's Hill sphere.[7]| Planet | Known Irregular Moons | Semi-Major Axis Range (million km) |

|---|---|---|

| Jupiter | 89 | 11–50 |

| Saturn | 250 | 20–60 |

| Uranus | 10 | 3–12 |

| Neptune | 9 | 5–50 |

Origin and Capture Mechanisms

The primary theory for the origin of irregular moons posits that they were captured from heliocentric orbits during periods of dynamical instability in the early Solar System, particularly through the scattering of planetesimals by migrating giant planets as described in the Nice model.[20] In this framework, the giant planets underwent significant orbital migration after their formation, with Jupiter and Saturn crossing a 1:2 mean-motion resonance around 4 AU from the Sun, leading to excitation of eccentricities and close encounters that scattered nearby planetesimals from the primordial disk. This instability, occurring roughly 100-800 million years after planet formation, provided the chaotic environment necessary for temporary binding of these objects into bound orbits around the planets, rather than in situ formation from circumplanetary disks. Capture mechanisms generally require energy dissipation to bind passing planetesimals, with three-body gravitational encounters being the most widely invoked process for irregular moons. In such encounters, a planetesimal interacts closely with a planet and a perturber (another planet or satellite), allowing temporary capture into highly eccentric and inclined orbits through gravitational slingshot effects; this mechanism is particularly effective during the planetary scattering phases of the Nice model and can produce both prograde and retrograde orbits depending on the encounter geometry. Alternative mechanisms include gas drag within the nebular phase, where frictional forces in the giant planets' extended gaseous envelopes decelerate incoming bodies, though this is more viable for larger progenitors that may fragment upon capture; and tidal capture, involving energy loss through tidal bulges raised on the planet or satellite, which is rare for small, low-mass irregular moons due to insufficient tidal dissipation. Evidence supporting capture from outer Solar System populations includes the compositional similarities between irregular moons and objects in the Kuiper Belt and scattered disk, such as neutral to red spectra indicative of carbonaceous materials and organics, as observed in spectroscopic surveys of Jovian and Saturnian irregulars. Additionally, the prevalence of retrograde orbits—comprising over 80% of known irregular moons—arises from hyperbolic encounters where the incoming velocity vector aligns to produce high inclinations greater than 90°, a signature inconsistent with in situ formation but expected from dynamical capture. The role of planetary migration is central, as Jupiter and Saturn's resonance passage scattered planetesimals inward, increasing encounter rates and enabling captures around outer planets like Uranus and Neptune, while Jupiter's irregulars may reflect earlier or distinct events. The probability of capture is quantified by the effective cross-section for gravitational encounters, approximated as , where and are the planetary and satellite radii, is the escape velocity from the planet-satellite system, and is the hyperbolic excess velocity of the incoming body; this enhancement over the geometric cross-section accounts for gravitational focusing, making capture feasible even at relative speeds of several km/s typical in the Nice model simulations.Long-term Stability

The long-term stability of irregular moons is influenced by several key perturbations that drive orbital precession and chaotic evolution. Solar tides induce eccentricity oscillations through mechanisms like the evection resonance, particularly affecting prograde orbits at larger semimajor axes, while planetary oblateness (modeled via the J₂ term) slightly amplifies instabilities by reducing pericenter distances during these cycles. Mutual interactions among the moons contribute to chaotic scattering, with close encounters leading to precession rates that can destabilize clusters over gigayear timescales.[21][15] Most irregular moons maintain stable orbits over the 4.5 Gyr age of the Solar System, but stability varies with distance from the parent planet. Close-in irregulars, those with semimajor axes less than approximately 30 planetary radii (R_p), are highly unstable due to strong gravitational influences from inner regular satellites and planetary oblateness, resulting in rapid ejections or collisions within short timescales. In contrast, distant irregulars beyond about 200 R_p are vulnerable to solar perturbations that can eject them from the system, leading to depletion near the outer edges of the Hill sphere (a/r_H > 0.5).[9][15] The Kozai-Lidov mechanism plays a critical role in destabilizing certain orbits, causing oscillations in inclination that couple with eccentricity spikes, particularly for inclinations between 55° and 130°. These oscillations can drive pericenter distances low enough to risk collisions with the planet or inner moons, or apocenter expansions that facilitate escape, with cycle periods as short as 65–180 years for retrograde and prograde cases, respectively. Orbits trapped in Kozai resonance represent only about 10% of the stable phase space over 10 Myr, explaining the observed inclination gaps in irregular populations.[21][9] N-body simulations of irregular moon populations over Solar System timescales reveal a typical loss rate of 10–20% from initial captures, primarily due to ejections and collisions, with prograde groups experiencing higher attrition (e.g., ~5 collisions expected over 4.5 Gyr). These models, integrating orbits under full perturbations, indicate that chaotic behavior dominates, characterized by Lyapunov times τ_L ≈ 10^5–10^7 years for affected orbits, beyond which predictability breaks down. For instance, simulations of Jovian irregulars show all known orbits remaining bound over 10^8 years, but with subtle chaotic transitions in resonant cases.[21][9][22] Differences in stability arise across planets due to varying population densities and dynamical environments. Saturn's denser irregular moon population, with over three times as many objects as Jupiter's down to similar sizes, elevates collision risks through frequent close encounters in its confined orbital volume, as evidenced by recent collisional families and estimates of short orbital periods fostering impacts.[23][7]Temporary Captures

Temporary satellites, also known as mini-moons or temporarily captured objects, are small solar system bodies that transition from hyperbolic heliocentric orbits to short-lived elliptic orbits around a planet, typically lasting from months to several years or even millennia.[24] These captures occur when an object's velocity relative to the planet is sufficiently low to allow gravitational binding without permanent retention. A prominent example is Earth's mini-moon 2020 CD3, a small asteroid approximately 1-6 meters in diameter that was captured around September 2018 and remained in geocentric orbit until escaping in May 2020.[24][25] For Jupiter, comet 147P/Kushida-Muramatsu serves as a key case, having been temporarily captured from 1949 to 1961, during which it completed two full revolutions in an irregular orbit before escaping.[26] The primary mechanisms for temporary captures involve low-velocity encounters between the incoming object and the planet, often during close flybys that reduce the object's hyperbolic excess velocity to near zero, enabling a brief elliptic phase.[27] Gravitational assists from the planet's moons or other bodies can further dissipate energy, while for terrestrial planets like Earth, aerobraking in the upper atmosphere may play a role in stabilizing the orbit momentarily.[27] In the case of gas giants such as Jupiter, three-body interactions during encounters with the planet's Hill sphere facilitate the capture, particularly for objects originating from unstable resonances like the quasi-Hilda group.[26] Such events are rare, with estimates indicating that fewer than 1% of near-miss asteroids achieve temporary capture, and the annual probability for Earth is on the order of 10^{-3} for objects with impact velocities below 14 km/s.[27] Detection relies on surveys like the Catalina Sky Survey, which identified 2020 CD3 through repeated observations revealing its geocentric motion, though many escapes go unnoticed due to the objects' faintness and short durations.[28] The typical capture duration can be approximated by the object's orbital period around the planet, given by the formula where is the semi-major axis, is the gravitational constant, and is the planet's mass; this is adjusted downward by energy dissipation mechanisms that limit stability to a few orbits.[27] These transient captures provide valuable testbeds for understanding the dynamics of permanent irregular moon formation, as they demonstrate the initial stages of three-body interactions and energy loss required for long-term retention, though no recent confirmations of extended captures by gas giants have been reported.Physical Characteristics

Size and Shape

Irregular moons exhibit a wide range of sizes, typically spanning diameters from approximately 1 km to 200 km, though the vast majority are smaller than 10 km in diameter. The largest confirmed irregular moon is Saturn's Phoebe, with a mean diameter of 213 km, while Jupiter's Himalia ranks as the next largest at about 170 km (estimates range from 140-170 km depending on albedo assumptions). These dimensions place irregular moons among the smaller satellites in the Solar System, far dwarfed by the major regular moons of the giant planets. Bulk densities, where measured, are low at around 1-1.6 g/cm³, indicating porous, icy structures. The size distribution of irregular moons follows a power-law relation in the differential form, where the number of moons per unit diameter interval scales as , with representing the diameter. This distribution mirrors that of captured outer Solar System asteroid or Kuiper Belt object populations from which irregular moons are believed to originate, indicating a collisional history that favors smaller bodies over time. Representative examples include clusters of sub-10 km moons around Jupiter and Saturn, where the abundance drops sharply for diameters exceeding 50 km. In terms of shape, irregular moons are generally non-spherical and elongated, often displaying axis ratios between major and minor axes of up to 2:1 or greater, as inferred from photometric variations. Their low self-gravity environments promote rubble-pile structures, consisting of loosely aggregated regolith and fragments held together primarily by mutual attraction rather than cohesive forces. For instance, Saturn's Kiviuq shows lightcurve amplitudes suggesting an axis ratio exceeding 1.8:1.[31] Sizes and shapes for most irregular moons are determined indirectly through disk-integrated photometry and analysis of rotational lightcurves, which reveal amplitude variations tied to elongation and provide estimates of effective radii assuming typical albedos around 0.04–0.06. Resolved imaging from spacecraft or high-resolution telescopes is rare, limited to closer or brighter examples like Phoebe, due to the faintness and remoteness of these objects. Discovery biases in early surveys, which prioritized brighter (larger) moons detectable with shallower exposures, have historically overrepresented bodies above 20 km, skewing initial population assessments until deeper modern observations revealed the prevalence of smaller ones.[32][7]Colors and Albedo

Irregular moons exhibit a range of surface colors from neutral gray to moderately red, as determined through broadband photometry in the visible wavelengths. Typical V-R color indices fall between 0.4 and 0.6 across the populations orbiting Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, with some objects reaching up to 0.65 for Saturn's retrograde satellites.[33][34] These colors align closely with those of C-, P-, and D-type asteroids in the outer main belt and Trojan populations, suggesting compositional similarities dominated by carbonaceous materials.[2][15] The albedos of irregular moons are notably low, ranging from 0.04 to 0.10, indicative of dark, primitive surfaces with minimal ice exposure. For instance, Saturn's Phoebe has a geometric albedo of approximately 0.06 to 0.08, while Jupiter's Himalia measures around 0.04.[9][7] This low reflectivity contrasts sharply with the higher albedos (0.5–0.9) of regular, ice-rich inner moons, highlighting the captured, asteroid-like nature of irregular satellites.[9] Variations in color exist among irregular moon populations, particularly for Saturn where retrograde objects tend to be redder (average V-R ≈ 0.55) and more dispersed than prograde ones (average V-R ≈ 0.50), potentially due to differential space weathering or diverse capture histories.[34] Such differences correlate loosely with orbital parameters like inclination, with higher-inclination satellites showing slightly redder hues in some cases.[33] Colors and albedos are primarily measured via B-V and V-R photometry from ground-based telescopes, providing efficient surveys of faint objects without resolving surface details.[33] These optical properties imply origins in the outer solar system, likely from captured planetesimals akin to centaurs or scattered disk objects, with post-capture collisional processing removing volatile ices and darkening surfaces.[9][2]Spectral Features

The spectra of most irregular moons display featureless continua across the near-infrared (NIR) range, characteristic of dark, primitive surfaces dominated by carbonaceous materials.[35] These flat or gently sloped spectra lack prominent absorption features in many cases, reflecting low-albedo regoliths composed primarily of complex organics and amorphous carbon. However, a subset exhibits subtle absorptions indicative of hydrated minerals, such as water ice bands at approximately 1.5 and 2.0 μm, most notably on Saturn's irregular moon Phoebe, where a broad 2.0 μm feature confirms the presence of H₂O ice mixed with dark, non-ice components.[36] Compositional analysis reveals that carbonaceous (C-type) spectra are dominant among irregular moons, with surfaces rich in silicates, phyllosilicates, and organic compounds akin to outer main-belt asteroids and centaurs.[35] D-type classifications, marked by redder slopes and featureless profiles, are rarer and typically associated with retrograde orbits, as seen in Jupiter's Carme, which shows a blue NIR slope up to 1.5 μm but overall primitive, carbon-rich traits including ilmenite and minnesotaite.[35] Key diagnostic signatures include a weak 0.7 μm absorption band attributed to Fe²⁺ → Fe³⁺ charge transfer in phyllosilicates, observed in a few prograde Jupiter irregulars like Himalia. Additionally, ultraviolet (UV) absorptions near 0.3–0.4 μm arise from tholin-like organics, contributing to the reddish hues in D-type examples.[37] NIR spectroscopy, primarily from ground-based telescopes such as the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) with the SpeX instrument and the Very Large Telescope (VLT), has been the primary method for probing these compositions, targeting brighter moons like Phoebe, Himalia, and Carme.[35] Data for fainter irregular moons remain limited due to their low albedos (typically 0.04–0.06) and small sizes, restricting analyses to broadband photometry or low-resolution spectra.[37] Spectral differences between planetary systems highlight dynamical histories: Jupiter's irregular moons often exhibit bluer slopes (less processed surfaces), consistent with C-type dominance and minimal irradiation, whereas Saturn's are generally redder, potentially from enhanced cosmic ray processing of organics over longer exposure times.[38] For instance, prograde Jupiter groups like Himalia show hydrated silicates without strong ice features, contrasting with Phoebe's exposed water ice.[35][36]Rotation

Irregular moons exhibit rotation periods ranging from approximately 5 hours to several days, reflecting their captured origins and lack of significant tidal synchronization due to their distant orbits. These periods are primarily determined through photometric lightcurve analysis, which captures brightness variations caused by the moons' irregular shapes as they rotate. Ground-based telescopes and space missions, such as Cassini's Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) for Saturn's irregulars and the Kepler K2 mission for Uranian satellites, have provided the bulk of these measurements, with radar observations limited by the moons' small sizes and great distances from Earth.[39] Representative examples illustrate this range across planetary systems. For Saturn, periods span 5.45 hours for the small moon Hati to 76.13 hours for Tarqeq, with Phoebe rotating every 9.27 hours based on Cassini flyby data. Among Jupiter's irregulars, Himalia has a period of 7.78 hours, while Carme spins in about 6.48 hours. Uranian irregulars show periods of 4 to 12 hours, such as Sycorax at 6.92 hours and Ferdinand at 11.84 hours. Neptune's largest irregular, Nereid, rotates with a period of 11.59 hours, confirmed by K2 observations. These values highlight a general tendency for periods in the hours-to-days regime, slower than many inner regular satellites but faster than synchronous locking would dictate.[39][40][41][42] Spin axis orientations among irregular moons are often misaligned with their orbital planes, a consequence of their eccentric capture histories and irregular shapes, which can lead to non-principal axis rotation in rubble-pile aggregates. However, observed lightcurves typically indicate stable principal-axis rotation rather than chaotic tumbling, though theoretical models suggest tumbling could occur in loosely bound structures subjected to impacts or torques. YORP-like effects from solar radiation, which alter spin rates in near-Sun asteroids, are negligible for these distant objects due to weak insolation. Few cases of confirmed tumbling exist, but dynamical stability analyses predict that most irregulars maintain fast, asynchronous spins without evolving to synchronous states.[43] A weak correlation appears between rotation period and size, with larger irregular moons tending to rotate more slowly, as seen in Saturn's population where prograde and brighter (larger) moons have longer periods on average. This may stem from collisional evolution dissipating spin energy in bigger bodies or from initial conditions at capture, rather than tidal torques, which follow a scaling but exert minimal influence at such distances. Anomalies include potential non-principal axis rotation in rubble-pile configurations, inferred from lightcurve complexities, though direct evidence remains sparse.[7]Groupings and Families

Dynamical Groupings

Dynamical groupings of irregular moons refer to clusters of satellites that share similar values in key orbital elements—semi-major axis (a), eccentricity (e), and inclination (i)—indicating they likely originated from the fragmentation of a common parent body via collision after capture. Recent discoveries, including 128 new irregular moons around Saturn announced in March 2025 and additional moons for Uranus and Neptune in 2024, have significantly expanded these groupings.[4][44] These clusters are identified through the computation of proper orbital elements, which average the instantaneous Keplerian elements over extended timescales (e.g., 10^8 years) to mitigate short-term perturbations from the planet and other bodies, followed by statistical clustering methods such as the Hellinger distance to measure similarities in the distribution of these elements.[45][46] Saturn hosts the largest number of such families among the giant planets, with Jupiter having the next largest; Saturn features multiple dynamical families, such as the prograde Inuit (i ≈ 45°–50°) and Gallic (i ≈ 37°) groups, along with several retrograde clusters like the Norse family. Jupiter has at least five major groupings containing multiple members, including the prograde Himalia family and the retrograde Pasiphae, Ananke (i ≈ 147°), and Carme (i ≈ 163°) families; these suggest up to eight distinct parent bodies. Uranus and Neptune exhibit fewer and less populous groupings, exemplified by Uranus's retrograde Caliban family (i ≈ 140°–144°), now including three members, and Neptune's Neso and Sao families, each with three members.[45][7][44] The compact nature of these groupings, characterized by spreads Δa typically under 1% of the mean semi-major axis and Δi below 5° (corresponding to ejection velocities δV of 5–80 m/s via D'Alembert characteristics), strongly implies formation through post-capture collisional breakup rather than independent captures, as random captures would produce broader dispersions.[46][45] Backward integration simulations of orbital evolution, combined with collisional modeling in planetesimal disks, confirm that the observed tight clusters can originate from single progenitors disrupted by impacts, with stability maintained over billions of years in the outer regions of the satellite systems.[46][45]Compositional Groupings

Irregular moons are grouped compositionally based on their surface colors and spectral properties, which provide insights into their material makeup and potential origins independent of orbital dynamics. Color clusters are typically defined using broadband photometry in filters such as V-R, where gray objects have V-R < 0.5 and redder ones exceed V-R > 0.7. For instance, Saturn's Norse group, including members like Ymir, exhibits red colors (V-R > 0.7) suggestive of D-type surfaces rich in organic materials, while Jupiter's Ananke group displays gray hues (V-R < 0.5) akin to C-type carbonaceous asteroids.[15][38] Spectral families further refine these groupings, with C-type spectra dominating among closer irregular moons due to their featureless, neutral reflectance consistent with primitive carbonaceous compositions. D-type spectra, characterized by steeper red slopes, prevail in more distant groups, such as Neptune's Psamathe subgroup, indicating exposure to solar radiation and space weathering that alters surface organics. These spectral distinctions are derived from visible to near-infrared observations, revealing water ice absorptions in some cases, like Phoebe's volatile-rich surface.[47][15] Principal component analysis (PCA) on color and spectral data is a primary method for identifying these clusters, reducing multidimensional photometric datasets to reveal natural groupings without assuming dynamical links. Albedo measurements complement this by highlighting low reflectivities (typically 0.04-0.10) across groups, though variations help separate families; for example, the Phoebe group in Saturn's retrograde population shows tight color clustering in red V-R space despite dynamical dispersion.[47][38] Key examples illustrate mismatches between compositional and dynamical groupings, such as the red Phoebe group (retrograde, Saturn) contrasting with grayer prograde clusters, implying multiple capture events from varied heliocentric populations. These discrepancies suggest that while some moons share dynamical clusters, their colors indicate diverse sources, with gray C-types possibly from the outer main belt and red D-types from the scattered disk or Kuiper Belt.[15][47]Evidence for Common Origins

The integration of dynamical clustering and compositional similarities provides compelling evidence that many irregular moon families originated from post-capture collisional disruptions of larger progenitor bodies. For instance, Jupiter's Carme group exhibits tight orbital clustering with velocity dispersions of 5–50 m/s, alongside homogeneous spectral slopes indicative of a shared parent body, suggesting fragmentation via impact with a planetesimal after capture.[48] Similarly, spectroscopic data reveal that Carme, Sinope, and Themisto share red colors and absorption features at 3.0 and 3.4 μm matching those of Jovian Trojans like Leucus, supporting a common origin in the primordial Kuiper Belt followed by capture and collision.[49] Numerical models of collisional evolution indicate that these families formed through breakup events occurring 1–4 billion years ago, when a residual planetesimal disk around the giant planets facilitated impacts. In such scenarios, fragments are ejected with low relative velocities typically below 100 m/s, allowing them to remain dynamically bound within similar orbital clusters while preserving compositional integrity.[50][48] These models predict cratering or partial disruptions of parent moons by ~1–2 km impactors, producing ejecta volumes on the order of 10¹⁷ cm³, consistent with observed family sizes.[48] A prominent case study is Saturn's Phoebe family within the broader Norse dynamical group, comprising nearly 200 known members as of 2025 with orbits clustered around Phoebe's inclination of ~173°. Evidence points to Phoebe as a fragmented progenitor, with a recent collisional event 0.1–2.8 Gyr ago grinding down the population to produce a steep size distribution (q ≈ 4.9) and an estimated total population far exceeding that of Jupiter's families.[23][51] Subgroups like the Phoebe subgroup (inclinations within 3° of Phoebe) show potential spectral affinities, including dark, C-type-like reflectance consistent with outer Solar System origins, though full homogeneity remains unconfirmed.[23] For Jupiter, the Ananke and Carme families illustrate fragmented progenitors, where impacts on ~30–50 km parents ejected fragments with Δv up to 80 m/s, forming clusters that have since undergone minimal dispersal.[48] Despite these synergies, challenges persist: not all dynamical groups exhibit matching compositions, such as the heterogeneous phyllosilicates in Jupiter's Himalia family, implying multiple independent captures rather than a single collisional event. Recent JWST observations, including NIRSpec spectroscopy targeting 3 μm features, have detected phyllosilicates in some Jovian irregulars, confirming varied hydration and origins across families and linking some to Trojan or Kuiper Belt analogs.[49][49] Variations in spectral slopes across Saturn's retrograde moons further suggest diverse impact histories or resurfacing.[50]Irregular Moons by Planet

Jupiter

Jupiter possesses 89 known irregular moons, comprising the majority of its 97 total confirmed satellites, with the remaining eight being closer-in, prograde regular moons.[5][52] Of these irregular moons, 16 follow prograde orbits while 73 are retrograde, reflecting a higher proportion of prograde satellites compared to the predominantly retrograde irregular populations around Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.[17] This distribution suggests distinct capture histories, potentially influenced by Jupiter's position and mass during early Solar System dynamics. The irregular moons orbit at semi-major axes ranging from approximately 11 to 50 million kilometers, with high eccentricities (typically 0.2–0.4) and inclinations exceeding 25° for prograde and 140° for retrograde orbits, placing them far beyond the planet's regular satellite system.[17] The irregular moons cluster into dynamical families believed to originate from collisional fragmentation of larger captured bodies. The largest prograde family is the Himalia group, with seven confirmed members including the namesake Himalia—the biggest irregular moon at about 170 km in diameter—and Elara, Lysithea, Leda, Dia, Ersa, and Pandia; these share orbits around 11.5 million km from Jupiter.[53] Among retrograde families, the Pasiphae group is the most populous with 11 members, led by Pasiphae (about 60 km across), followed by the Carme group with around 23 members centered on Carme (23 km diameter), and the smaller Ananke group. Notable examples include Callirrhoe, a prograde irregular moon discovered in 1999 via the Deep Lens Survey, with a diameter of roughly 9 km and an orbit at about 16 million km; it stands out for its relatively close-in position among outer satellites. Recent surveys, particularly using the Pan-STARRS telescope, contributed to confirming 12 additional irregular moons between 2021 and 2023, and in April 2025, two more were confirmed from archival data (S/2017 J 10 and S/2017 J 11), expanding knowledge of these faint, distant objects.[54] Jupiter's irregular moons exhibit a unique trait in having a greater fraction of prograde orbiters than other gas giants, possibly due to captures from the inner Solar System or interactions with Trojan asteroids during planetary migration.[49] Spectral analyses from the James Webb Space Telescope indicate varied compositions, with prograde members like those in the Himalia family showing ammoniated phyllosilicates suggestive of outer Solar System origins, while some retrograde moons may trace to captured centaurs or scattered disk objects.[49] This diversity underscores Jupiter's role as a gravitational scavenger, potentially incorporating material from multiple reservoirs.Saturn

Saturn possesses the largest known population of irregular moons in the Solar System, totaling approximately 250 as of 2025 following the announcement of 128 new discoveries in March of that year, derived from archival data collected by the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) between 2019 and 2023.[4] These additions nearly doubled the previously documented count of 121 irregular moons, highlighting Saturn's dynamical environment as particularly conducive to the capture and retention of distant, small bodies.[55] Unlike the planet's inner regular moons, which formed in situ, Saturn's irregular satellites are believed to be captured objects, primarily from the outer Solar System, exhibiting highly eccentric and inclined orbits that place them far from the planet.[23] The irregular moons cluster into distinct dynamical families based on orbital similarities, suggesting origins from collisional disruptions of larger progenitors. The Phoebe group, a retrograde family named after its largest member, now includes over 20 confirmed satellites with semimajor axes around 12-13 million kilometers and high inclinations near 170 degrees; Phoebe itself, with a mean diameter of 213 kilometers, is the most massive irregular moon and was closely studied during the Cassini spacecraft's flyby in 2004, revealing a dark, water-ice-poor surface indicative of a captured centaur-like body.[56][4] The Norse group, comprising the majority of retrograde irregulars (now totaling around 197 members post-2025 discoveries), features orbits with semimajor axes ranging from 11 to 28 million kilometers and inclinations of 136-173 degrees, often displaying neutral to moderately red colors consistent with primitive outer Solar System origins. In contrast, the prograde families include the red-hued Inuit group (centered on members like Paaliaq and Kiviuq, with recent additions expanding the Kiviuq subgroup to 17 members) and the gray or neutral-toned Gallic group (anchored by Albiorix), both occupying semimajor axes of roughly 16 million kilometers and lower inclinations around 40-50 degrees.[38][4] Orbitally, Saturn's irregular moons span semimajor axes primarily between 12 and 30 million kilometers, with a near-even split between prograde and retrograde orbits (approximately 50/50 overall, though small moons show a retrograde bias among recent finds).[7][57] This dense clustering in semi-major axis and inclination space fosters frequent close encounters and collisions, driving ongoing evolution through multi-generational cascades that fragment captured bodies into smaller fragments.[4] Notable examples include Siarnaq, the largest Inuit-group member at about 40 kilometers across, whose irregular, roughly triangular shape—evident from rotational lightcurve variations—exemplifies the elongated forms typical of collisionally evolved irregulars.[32] The 2025 discoveries have significantly advanced understanding of these systems by populating sparse regions in orbital parameter space, confirming collisional origins for families like Kiviuq and Mundilfari (the latter implying a disruption event around 100 million years ago), and resolving prior ambiguities in dynamical groupings that suggested fewer than a dozen progenitor bodies for the entire irregular population.[4] This influx underscores Saturn's unique role in preserving captured irregular moons, outnumbering those of Jupiter and providing key insights into early Solar System capture processes without direct spacecraft revisits beyond Cassini's legacy observations.[23]Uranus

Uranus possesses a modest population of 10 irregular moons as of 2025, significantly fewer than those of Jupiter or Saturn. No new irregular satellites have been confirmed since 2024, with the recently discovered S/2025 U 1 classified as an inner regular moon orbiting close to the planet's ring system. These outer satellites are faint and distant, complicating observations and contributing to limited data on their physical properties; the Voyager 2 flyby in 1986 imaged only the closer irregulars but provided scant details due to their remoteness. Their orbits lie far beyond the major moons, with semi-major axes spanning approximately 4 to 21 million kilometers, and nearly all exhibit high eccentricities exceeding 0.2, leading to elongated paths that bring them periodically closer to Uranus.[58] Approximately 90% of Uranus's irregular moons follow retrograde orbits, inclined at angles greater than 90 degrees relative to the planet's equator, contrasting with the prograde motion of its inner satellites. Key dynamical groupings include the Caliban cluster—comprising the retrograde moons Caliban, Prospero, Setebos, and Stephano—at semi-major axes of 6–7 million kilometers, and the more distant Sycorax, which stands alone in its orbital regime around 12 million kilometers, also retrograde. Margaret represents the sole prograde irregular moon, with an inclination of about 73 degrees and extreme eccentricity near 0.66, while Ferdinand holds the distinction of the farthest, at roughly 21 million kilometers. These groupings suggest possible common origins, though dynamical models indicate the satellites do not form tight clusters like those around Jupiter, likely due to perturbations from the Sun and other factors.[59][60] Among these, Sycorax is the largest and most prominent, with an estimated diameter of 150 kilometers and an exceptionally low geometric albedo of about 0.04, rendering it one of the darkest known moons in the Solar System and implying a surface rich in opaque, low-reflectivity materials. The overall scarcity of irregular moons around Uranus, compared to the gas giants, stems from observational difficulties: the planet's great distance (19 AU from the Sun) and low intrinsic brightness hinder detection of faint objects against the stellar background. Their capture is believed to have occurred early in the Solar System's history, potentially facilitated by dynamical instability during the giant impact that tilted Uranus's axis to nearly 98 degrees, though direct evidence remains elusive.[61]Neptune

Neptune possesses nine known irregular moons as of 2025, including the large captured satellite Triton and eight smaller outer bodies, two of which were confirmed via ground-based observations in 2024.[62] These irregular moons are characterized by their distant, eccentric, and highly inclined orbits, indicative of capture origins rather than in situ formation, with semi-major axes ranging from approximately 5 to 50 million kilometers for the outer group. Triton stands apart as the largest captured moon in the Solar System, with a diameter of about 2,700 kilometers and a nearly circular orbit at just 355,000 kilometers from Neptune, though its retrograde motion and composition suggest it was gravitationally seized from the Kuiper Belt early in the planet's history.[63] Despite its proximity, likely resulting from tidal circularization over billions of years, Triton remains geologically active, exhibiting cryovolcanic geysers and a thin nitrogen atmosphere, as revealed by Voyager 2 flyby data.[63] Among the smaller irregular moons, Nereid is the most prominent, with a diameter of roughly 340 kilometers and an exceptionally eccentric retrograde orbit that varies from 1.4 to 9.7 million kilometers from Neptune.[42] Its lightcurve displays significant variability, attributed to irregular shape or surface features, with rotational periods and brightness fluctuations observed over decades.[64] The remaining seven moons form loose dynamical groupings: Nereid represents a unique eccentric retrograde population, while the distant prograde group, including Psamathe and Neso, orbits at semi-major axes exceeding 45 million kilometers with low eccentricities and inclinations around 25–30 degrees. Psamathe and Neso, both under 50 kilometers in diameter, exemplify this cluster, potentially sharing a collisional origin based on similar orbital alignments.[65] The 2024 discoveries—S/2002 N5 and S/2021 N1—expanded Neptune's irregular retinue, detected using deep imaging with telescopes like Magellan, Subaru, and the Very Large Telescope, and confirmed through orbital tracking.[66] S/2002 N5, approximately 23 kilometers across, follows a prograde orbit akin to Sao and Laomedeia at about 9 years' period, while S/2021 N1, around 14 kilometers, joins the Psamathe-Neso group with a 27-year orbit and apparent magnitude exceeding 25, marking it as the faintest moon yet found by ground-based means.[62] These additions highlight ongoing efforts to map faint outer satellites, reinforcing the captured nature of Neptune's irregular system through their retrograde dominance (six of nine) and clustered dynamics.Exploration and Observations

Historical Discoveries

The discovery of irregular moons began in the late 19th century with the identification of Phoebe, Saturn's largest irregular satellite, on photographic plates taken on August 16, 1898, at the Boyden Observatory in Peru by DeLisle Stewart, though it was formally announced by William H. Pickering in 1899.[56] Phoebe's retrograde orbit distinguished it as the first known irregular moon, captured from the outer Solar System rather than formed in situ.[1] Early 20th-century discoveries focused on Jupiter's outer irregular moons, starting with Himalia on December 3, 1904, by Charles D. Perrine using the Crossley reflector at Lick Observatory. This was followed by Elara in 1905 (also by Perrine), Pasiphaë in 1908 (Philipp H. M. Melotte at Greenwich Observatory), Sinope in 1914 (Seth B. Nicholson at Lick), Lysithea and Carme in 1938 (Nicholson at Mount Wilson), Ananke in 1951 (Nicholson at Palomar Observatory), and Leda in 1974 (Nicholson at Palomar). These eight prograde and retrograde satellites were detected via photographic plates, revealing Jupiter's distant, inclined orbits but limited by the technology's sensitivity to fainter objects.[11] By the late 20th century, attention shifted to Uranus and Neptune following Voyager 2's flybys in 1986 and 1989, which highlighted the need for ground-based searches of faint irregulars. In 1997, Brett Gladman and colleagues discovered Uranus's first irregular moons, Caliban and Sycorax, using the 5.1-meter Hale Telescope at Palomar Observatory, marking the first such detections for that planet.[67] Additional Uranian irregulars, including Prospero, Setebos, and Stephano, were found in 1999 by Gladman et al. at the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT).[68] For Neptune, beyond the earlier Nereid (discovered 1949), the 1990s searches yielded no new irregulars until the early 2000s, with Gladman contributing to later efforts. Pre-2000, fewer than 20 irregular moons were known across all giant planets, biased toward brighter, larger examples detectable by photographic methods. The advent of charge-coupled device (CCD) imagers in the 2000s revolutionized surveys, enabling deeper searches at facilities like Palomar and Mauna Kea. In 2000, Gladman et al. announced 12 new Saturnian irregular moons, including the Norse group (e.g., Ymir, Skathi), observed with telescopes worldwide, expanding Saturn's known irregulars beyond Phoebe. Scott S. Sheppard and David Jewitt's Palomar and Subaru surveys in the early 2000s added over 50 irregular moons to Jupiter and Saturn, using CCDs to detect objects down to magnitudes of 24.[69] The Pan-STARRS telescope in the 2010s further contributed, with Sheppard et al. identifying additional Jupiter and Saturn irregulars through wide-field imaging. Milestones continued into the 2020s, such as the CFHT survey using 2023 data to confirm 128 new Saturnian irregulars, announced in 2025.[4]Spacecraft Missions

Spacecraft missions have offered sparse but valuable close-range insights into irregular moons, primarily as secondary targets during explorations of their parent planets. The most detailed encounter occurred on June 11, 2004, when NASA's Cassini spacecraft flew by Saturn's largest irregular satellite, Phoebe, at a minimum distance of 2,068 km and a relative velocity of about 5.8 km/s.[70] High-resolution images from Cassini's Imaging Science Subsystem revealed a rugged, ancient surface scarred by craters up to 10 km in diameter, with layered ejecta suggesting past internal activity or impacts. Spectroscopic data from the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) identified water ice mixed with a dark, reddish mantle rich in complex organics, carbon dioxide, phyllosilicates, and possible nitriles, indicating Phoebe's origin as a captured trans-Neptunian object from the Kuiper Belt. For Neptune, Voyager 2 provided the only spacecraft observations of its irregular moon Nereid during the 1989 flyby, acquiring images from distances of several million kilometers, with positional accuracies of 70–800 km.[71] These distant views captured Nereid's phase-dependent photometry across solar phase angles of 25° to 96°, revealing small rotational amplitude less than 0.15 magnitudes and a reddish spectrum consistent with a captured outer solar system body.[71] No geysers or active features were detected, underscoring Nereid's inert nature. Ground-based observations have shown large-amplitude brightness variations up to 1.83 magnitudes for Nereid. At Jupiter, NASA's Galileo orbiter (1995–2003) conducted distant observations of several irregular satellites, including resolved images of Elara, Lysithea, and Leda, marking the first spacecraft views of these objects and depicting their irregular shapes, such as Elara at approximately 80 km in diameter.[72] These low-resolution data, taken during orbital passes at distances of millions of kilometers, refined orbital elements and supported dynamical models of capture from the asteroid belt.[72] NASA's Juno mission, arriving in 2016 and ongoing as of 2025, has not prioritized irregular moons, focusing instead on the planet's atmosphere and inner Galilean satellites with its instruments ill-suited for distant faint targets. No spacecraft has closely approached Uranus's irregular moons, as Voyager 2's 1986 flyby predated their discovery and focused on the classical satellites; subsequent missions have bypassed the system. Overall, the absence of dedicated flybys highlights the challenges of targeting these distant, small bodies, with most insights derived from opportunistic remote sensing during primary objectives. These limited datasets have nonetheless confirmed compositional links within dynamical families, such as Phoebe's materials matching those inferred for its collisional fragments in Saturn's retrograde group.Recent Developments