Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Jarmo

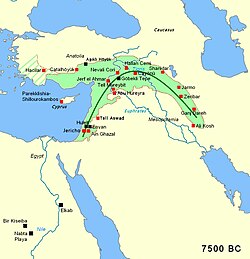

View on WikipediaJarmo (Kurdish: چەرمۆ, romanized: Çermo or Qelay Çermo, also Qal'at Jarmo) is a prehistoric archeological site located in modern Iraqi Kurdistan on the foothills of the Zagros Mountains. It lies at an altitude of 800 m above sea-level in a belt of oak and pistachio woodlands in the Adhaim River watershed. Excavations revealed that Jarmo was an agricultural community dating back to around 7090 BC. It was broadly contemporary with other important Neolithic sites such as Jericho in the Southern Levant and Çatalhöyük in Anatolia.

Key Information

Discovery and excavation

[edit]The site was originally discovered by the Iraqi Directorate of Antiquities in 1940, and later became known to archaeologist Robert Braidwood from the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. At the time, he was looking for suitable places to research the origins of the Neolithic Revolution.[1][2] Braidwood worked as part of the Iraq-Jarmo programme for three seasons, those of 1948, 1950-1951 and 1954-1955; a fourth campaign, to be carried out in 1958-1959 did not come about because of the 14 July Revolution. During the excavations in Jarmo in 1954-1955, Braidwood used a multidisciplinary approach for the first time, in an attempt to refine the research methods and clarify the origin of the domestication of plants and animals. Among his team were a geologist, Herbert Wright, a palaeo-botanist, Hans Helbaek, an expert in pottery and radio-carbon dating, Frederic Mason, and a zoologist, Charles Reed, as well as a number of archaeologists. The interdisciplinary method was subsequently used in all serious field work in archaeology.

Jarmo, the village

[edit]

The excavations exposed a small village, covering an area of 12,000 to 16,000 m2, and which has been dated (by carbon-14) to 7090 BC, for the oldest levels, to 4950 BC for the most recent. The entire site consists of twelve levels. Jarmo appears to be two older, permanent Neolithic settlements and, approximately, contemporary with Jericho or the Neolithic stage of Shanidar. The high point is likely to have been between 6200 and 5800 BC. This small village consisted of some twenty five houses, with adobe walls and sun-dried mud roofs, which rested on stone foundations, with a simple floor plan dug from the earth. These dwellings were frequently repaired or rebuilt. In all, about 150 people lived in the village, which was clearly a permanent settlement. In the earlier phases there is a preponderance of objects made from stone, silex—using older styles—and obsidian. The use of this latter material, obtained from the area of Lake Van, 200 miles away, suggests that some form of organized trade already existed, as does the presence of ornamental shells from the Persian Gulf. In the oldest level baskets have been found, waterproofed with pitch, which is readily available in the area.

Agriculture and cattle farming

[edit]Agricultural activity is attested by the presence of stone sickles, cutters, bowls and other objects, for harvesting, preparing and storing food, and also by receptacles of engraved marble. In the later phases instruments made of bone, particularly perforating tools, buttons and spoons, have been found. Further research has shown that the villagers of Jarmo grew wheat of two types, emmer and einkorn, a type of primitive barley and lentils (it is common to record the domestication of grains, less so of pulses). Their diet, and that of their animals, also included species of wild plant, peas, acorns, carob seeds, pistachios and wild wheat. Snail shells are also abundant. There is evidence that they had domesticated goats, sheep and dogs. On the higher levels of the site pigs have been found, together with the first evidence of pottery.

Pottery and religion

[edit]Jarmo is one of the oldest sites at which pottery has been found, appearing in the most recent levels of excavation, which dates it to the 7th millennium BC. This pottery is handmade, of simple design and with thick sides, and treated with a vegetable solvent. There are clay figures, zoomorphic or anthropomorphic, including figures of pregnant women which are taken to be fertility goddesses, similar to the Mother Goddess of later Neolithic cultures in the same region. These constitute the inception of the Art of Mesopotamia.

Gallery

[edit]-

Jarmo, March 2021. Remains of the 1948-1955 excavations conducted by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago

-

Jarmo, March 2021, recent excavations by a Japanese team were conducted on the previous excavations carried out by the Oriental Institute between 1948 and 1955

-

Jarmo, March 2021. Remains of the 1948-1955 excavations conducted by the Oriental Institute

-

Fragments of alabaster jars, Jarmo circa 7500 BCE, before the 7000 BCE invention of pottery in the region. Louvre Museum

-

Pottery bowl, 7100-5800 BCE, from Jarmo

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Braidwood, Linda S; University of Chicago; Oriental Institute; Iraq-Jarmo Prehistoric Project (1950-1955) (1983). Prehistoric archeology along the Zagros Flanks (PDF). Chicago, Ill.: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. OCLC 679889989.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Robert J. Braidwood, The Iraq-Jarmo Project of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Season 1954–1955, Verlag nicht ermittelbar, 1954

Further reading

[edit]- Adovasio, James M. (1975). "The Textile and Basketry Impressions from Jarmo". Paléorient. 3 (1): 223–230. doi:10.3406/paleo.1975.4198.

- Braidwood, Robert J.; Braidwood, Linda (1950). "Jarmo: A Village Early Farmers in Iraq". Antiquity. 24 (96): 189–195. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00023371. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 162520880.

- TSUNEKI, Akira, et al., "PRELIMINARY REPORT OF THE CHARMO (JARMO) PREHISTORIC INVESTIGATIONS", 2023." ラーフィダーン 45, pp. 1-47, 2024

,_late_8th_century_BCE_to_late_6th_century_BCE._Sulaymaniyah,_Iraq,_March_2021._Aftermaths_of_1948-1955_excavations_conducted_by_the_Oriental_Institute_of_Chicago.jpg/250px-thumbnail.jpg)

,_late_8th_century_BCE_to_late_6th_century_BCE._Sulaymaniyah,_Iraq,_March_2021._Aftermaths_of_1948-1955_excavations_conducted_by_the_Oriental_Institute_of_Chicago.jpg/2000px-thumbnail.jpg)