Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

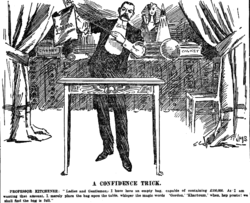

A scam, or a confidence trick, is an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their trust. Confidence tricks exploit victims using a combination of the victim's credulity, naivety, compassion, vanity, confidence, irresponsibility, and greed. Researchers have defined confidence tricks as "a distinctive species of fraudulent conduct ... intending to further voluntary exchanges that are not mutually beneficial", as they "benefit con operators at the expense of their victims (the 'marks')".[1]

Terminology

[edit]Other terms for "scam" include confidence trick, con, con game, confidence game, confidence scheme, ripoff, stratagem, finesse, grift, hustle, bunko, bunco, swindle, flimflam, gaffle, and bamboozle.

The perpetrator is often referred to as a scammer, confidence man, con man, con artist, grifter, hustler, or swindler. The intended victims are known as marks, suckers, stooges, mugs, rubes, or gulls (from the word gullible). When accomplices are employed, they are known as shills.[2]

Length

[edit]A short con or small con is a fast swindle that takes just minutes, possibly seconds. It typically aims to rob the victim of their money or other valuables that they carry on their person or are guarding.[3] A long con or big con (also, chiefly in British English, long game)[4] is a scam that unfolds over several days or weeks; it may involve a team of swindlers, and even props, sets, extras, costumes, and scripted lines. It aims to rob the victim of a huge amount of money or other valuables, often by getting them to empty out banking accounts and borrow from family members.[5]

History

[edit]The shell game dates back at least to ancient Greece.[6] William Thompson (1821–1856) was the original "confidence man". Thompson was a clumsy swindler who asked his victims to express confidence in him by giving him money or their watch rather than gaining their confidence in a more nuanced way. A few people trusted Thompson with their money and watches.[7] Thompson was arrested in July 1849. Reporting on this arrest, James Houston, a reporter for the New York Herald, publicized Thompson by naming him the "Confidence Man".[7] Although Thompson was an unsuccessful scammer, he gained a reputation as a genius operator mostly because Houston's satirical tone was not understood as such.[7] The National Police Gazette coined the term "confidence game" a few weeks after Houston first used the name "confidence man".[7]

Stages

[edit]In Confessions of a Confidence Man, Edward H. Smith lists the "six definite steps or stages of growth" of a confidence game.[8] He notes that some steps may be omitted. It is also possible some can be done in a different order than below, or carried out simultaneously.

- Foundation work

- Preparations are made in advance of the game, including the hiring of any assistants required and studying the background knowledge needed for the role.

- Approach

- The victim is approached or contacted.

- Build-up

- The victim is given an opportunity to profit from participating in a scheme. The victim's greed is encouraged, such that their rational judgment of the situation might be impaired.

- Pay-off or convincer

- The victim receives a small payout as a demonstration of the scheme's purported effectiveness. This may be a real amount of money or faked in some way (including physically or electronically). In a gambling con, the victim is allowed to win several small bets. In a stock market con, the victim is given fake dividends.

- The "hurrah"

- A sudden manufactured crisis or change of events forces the victim to act or make a decision immediately. This is the point at which the con succeeds or fails. With a financial scam, the con artist may tell the victim that the "window of opportunity" to make a large investment in the scheme is about to suddenly close forever.

- The in-and-in

- A conspirator (in on the con, but assumes the role of an interested bystander) puts an amount of money into the same scheme as the victim, to add an appearance of legitimacy. This can reassure the victim, and give the con man greater control when the deal has been completed.

In addition, some games require a "corroboration" step, particularly those involving a fake, but purportedly "rare item" of "great value". This usually includes the use of an accomplice who plays the part of an uninvolved (initially skeptical) third party, who later confirms the claims made by the con man.[8]

In a Long Con

[edit]Alternatively, in The Big Con, David Maurer writes that all cons "progress through certain fundamental stages" and that there are ten stages for a "big con."[9]

- Locating and investigating a well-to-do victim. (Putting the mark up.)

- Gaining the victim’s confidence. (Playing the con for him.)

- Steering him to meet the insideman. (Roping the mark.)

- Permitting the insideman to show him how he can make a large amount of money dishonestly. (Telling him the tale.)

- Allowing the victim to make a substantial profit. (Giving him the convincer.)

- Determining exactly how much he will invest. (Giving him the breakdown.)

- Sending him home for this amount of money. (Putting him on the send.)

- Playing him against a big store and fleecing him. (Taking off the touch.)

- Getting him out of the way as quietly as possible. (Blowing him off.)

- Forestalling action by the law. (Putting in the fix.)

Vulnerability factors

[edit]Confidence tricks exploit characteristics such as greed,[9] dishonesty, vanity, opportunism, lust, compassion, credulity, irresponsibility, desperation, and naïvety. As such, there is no consistent profile of a confidence trick victim; the common factor is simply that the victim relies on the good faith of the con artist. Victims of investment scams tend to show an incautious level of greed and gullibility, and many con artists target the elderly and other people thought to be vulnerable, using various forms of confidence tricks.[10] Researchers Huang and Orbach argue:[1]

Cons succeed for inducing judgment errors—chiefly, errors arising from imperfect information and cognitive biases. In popular culture and among professional con men, the human vulnerabilities that cons exploit are depicted as "dishonesty", "greed", and "gullibility" of the marks. Dishonesty, often represented by the expression "you can't cheat an honest man", refers to the willingness of marks to participate in unlawful acts, such as rigged gambling and embezzlement. Greed, the desire to "get something for nothing", is a shorthand expression of marks' beliefs that too-good-to-be-true gains are realistic. Gullibility reflects beliefs that marks are "suckers" and "fools" for entering into costly voluntary exchanges. Judicial opinions occasionally echo these sentiments.

Online fraud

[edit]Fraud has rapidly adapted to the Internet. The Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) of the FBI received 847,376 reports in 2021 with a reported loss of money of $6.9 billion in the US alone.[11] The Global Anti Scam Alliance annual Global State of Scam Report, stated that globally $47.8 billion was lost and the number of reported scams increased from 139 million in 2019 to 266 million in 2020.[12]

Government organizations have set up online fraud reporting websites to build awareness about online scams and help victims make reporting of online fraud easier. Examples are in the United States (FBI IC3, Federal Trade Commission), Australia (ScamWatch ACCC), Singapore (ScamAlert[13]), United Kingdom (ActionFraud), Netherlands (FraudeHelpdesk[14]). In addition, several private, non-profit initiatives have been set up to combat online fraud like AA419 (2004), APWG (2004) and ScamAdviser (2012).

In popular culture

[edit]- The Grifters is a noir fiction novel by Jim Thompson published in 1963. It was adapted into a film of the same name, directed by Stephen Frears and released in 1990. Both have characters involved in either short con or long con.

- The Sting is a 1973 American film directed by George Roy Hill largely concerned with a long con.

See also

[edit]- Advance-fee scam

- Badger game

- Boiler room (business)

- Catfishing

- Charlatan

- Confidence tricks in film and television

- Confidence tricks in literature

- Counterfeit

- Elmer Gantry (novel) – fictional religious cons

- Gaslighting

- Graft

- Hijacked journals

- List of con artists

- List of scams

- Phishing

- Pig butchering scam

- Quackery

- Racketeering

- Ripoff

- Scam baiting

- Scams in intellectual property

- Social engineering (security)

- SSA impersonation scam

- Technical support scam

- White-collar crime

References

[edit]- ^ a b Huang, Lindsey; Orbach, Barak (2018). "Con Men and Their Enablers: The Anatomy of Confidence Games". Social Research: An International Quarterly. 85 (4): 795–822. doi:10.1353/sor.2018.0050. S2CID 150021652. Archived from the original on 2023-01-15. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- ^ Maurer 1999, Ch. 9. The Con Man and His Lingo

- ^ Maurer 1999, Ch. 8. Short-Con Games

- ^ Yagoda, Ben (June 5, 2012). "The long game". Not One-off Britishisms. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. This language blog, while not a reliable etymological source, provides statistically gathered usage data that demonstrates neutral as well as critical usage, and that it is of British origin, only recently making notable inroads into American English.

- ^ Reading 2012, Ch. 1. Confidence

- ^ "Shell Game". Archived from the original on 2011-07-14.

- ^ a b c d Braucher, Jean; Orbach, Barak (2015). "Scamming: The Misunderstood Confidence Man". Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities. 72 (2): 249–292. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2314071. S2CID 148270133.

- ^ a b Smith, Edward H. (1923). Confessions of a Confidence Man: A Handbook for Suckers. Scientific American Publishing. pp. 35–37. Archived from the original on 2023-01-15. Retrieved 2015-11-07.

- ^ a b Maurer 1999, Ch. 1. A Word About Confidence Men

- ^ Crimes-of-persuasion.com Archived 2007-04-15 at the Wayback Machine Fraud Victim Advice / Assistance for Consumer Scams and Investment Frauds

- ^ "Internet Crime Report, 2021" (PDF). Internet Crime Complaint Center, FBI. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-22.

- ^ Greening, James (2021-12-07). "Scammers are Winning: € 41.3 ($ 47.8) Billion lost in Scams, up 15%". GASA. Archived from the original on 2022-05-17. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- ^ "ScamAlert - Bringing you the latest scam info". Default. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "Home". www.fraudehelpdesk.nl. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Bell, J. Bowyer; Whaley, Barton (1982). Cheating and Deception (reprint 1991). Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0887388682.

- Blundell, Nigel (1984) [1982]. The World's Greatest Crooks and Conmen and other mischievous malefactors. Octopus Books. ISBN 978-0706421446.

- Dillon, Eamon (2008) [2008]. The Fraudsters: Sharks and Charlatans – How Con Artists Make Their Money. Merlin Publishing. ISBN 978-1903582824.

- Ford, Charles V. (1999) [1999]. Lies! Lies!! Lies!!!: The Psychology of Deceit. American Psychiatric. ISBN 978-0880489973.

- Harper, Kimberly (2025). Men of No Reputation: Robert Boatright, the Buckfoot Gang, and the Fleecing of Middle America. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 9781682262450.

- Henderson, Les (2000). Crimes of Persuasion: Schemes, scams, frauds. Coyote Ridge. ISBN 978-0968713303.

- Kaminski, Marek M. (2004). Games Prisoners Play. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691117218.

- Konnikova, Maria (2016). The Confidence Game: Why We Fall for It...Every Time. Viking. ISBN 978-0525427414.

- Lazaroff, Steven; Rodger, Mark (2018) [2018]. History's Greatest Deceptions and Confidence scams. Rodger & Laz Publishing S.E.N.C. ISBN 978-1775292128.

- Maurer, David W. (1999) [1940]. The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man and the Confidence Game. Bobbs Merrill / Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0385495387.

- Maurer, David W. (1974). The American Confidence Man. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, Publisher. ISBN 978-0398029746.

- Reading, Amy (2012). The Mark Inside: A Perfect Swindle, a Cunning Revenge, and a Small History of the Big Con. Knopf. ISBN 978-0307473592.

- Smith, Jeff (2009). Soapy Smith: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel. Juneau: Klondike Research. ISBN 978-0981974309.

- Sutherland, Edwin Hardin (1937). The Professional Thief (reprint 1989). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226780511.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Weil, J.R. "Yellow Kid" (1948) [2004]. Con Man: A Master Swindler's Own Story. Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0767917377.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Zhang, Yingyu (2017). The Book of Swindles: Selections from a Late Ming Collection. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231178631.

External links

[edit] Scam travel guide from Wikivoyage

Scam travel guide from Wikivoyage Media related to Confidence tricks at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Confidence tricks at Wikimedia Commons- "Arrest of the Confidence Man". The Lost Museum, (GMU). Police Intelligence. New York Herald. July 8, 1849.

- "Book of Swindles". ChinaFile. 2017-11-15. Confidence tricks in China.

- "Prepaid funeral scam". FBI.gov.

- "To Catch a Con Man". Dateline NBC investigation. Archived from the original on 2007-03-24.

Definition and Terminology

Core Concepts and Distinctions

A scam constitutes a deliberate act of deception designed to induce a victim to voluntarily surrender money, assets, or sensitive information under false pretenses, typically by first establishing trust.[9] This process exploits psychological vulnerabilities, such as greed, fear, or sympathy, to manipulate decision-making.[10] Unlike routine business transactions, scams hinge on material misrepresentations that the perpetrator knows to be false, with the specific intent to cause reliance leading to the victim's loss.[11] Central to scams are four foundational elements derived from fraud principles: a false statement or omission of fact that is significant to the victim's choice; the scammer's awareness of its falsity; purposeful inducement of the victim's action or inaction; and the victim's reasonable dependence resulting in demonstrable harm, such as financial detriment.[12] [11] These elements distinguish scams from mere errors or puffery in advertising, where no knowing deceit for gain occurs. Scammers often employ narratives promising improbable returns or urgent resolutions to crises, bypassing rational scrutiny.[13] Scams represent a subset of fraud characterized by the victim's conscious involvement, contrasting with unauthorized frauds like account takeovers where access is illicitly obtained without consent.[9] [14] In scams, the perpetrator engineers voluntary compliance through social engineering tactics, such as impersonation or fabricated emergencies, rather than technical breaches.[15] This distinction underscores scams' reliance on interpersonal dynamics over systemic vulnerabilities, though both fall under broader criminal fraud statutes involving intentional deception for unjust gain.[12] Further delineations separate scams from hoaxes, which involve deception primarily for publicity, amusement, or ideological ends without direct pecuniary extraction from individuals.[16] Scams, by contrast, prioritize tangible profit, often escalating to identity theft or asset diversion post-deception. Confidence tricks, synonymous with scams, emphasize the "con" artist's role in building rapport to lower defenses, a tactic evident in schemes from street-level hustles to sophisticated online operations.[9]Etymology and Legal Definitions

The term "scam" entered American English as slang in the mid-20th century, with its earliest documented uses appearing around 1958 to 1963, primarily in the context of carnival or fairground deception.[17][18] Its etymology remains obscure, though it likely derives from earlier slang associated with trickery, possibly the 19th-century British "scamp," denoting a rogue or swindler who cheats through dishonest means.[18] Alternative hypotheses include connections to Danish "skam" (meaning shame or disgrace, implying moral culpability in deception) or Irish "cam" (crooked), but these lack definitive evidence and reflect speculative linguistic tracing rather than confirmed roots.[19] By the 1960s, "scam" had broadened from niche argot to general usage for any fraudulent trick or scheme aimed at financial gain, gaining prominence amid rising awareness of consumer cons in post-war America.[20] In legal contexts, "scam" lacks a standalone statutory definition in major jurisdictions like the United States, where it functions as a colloquial descriptor for deceptive practices prosecuted under broader fraud statutes rather than as a codified offense.[21] Federal law, for instance, addresses scams through provisions like 18 U.S.C. § 1341 (mail fraud), which penalizes any "scheme or artifice to defraud" executed via the postal service or interstate wires, requiring intent to deceive for monetary or property gain, with penalties up to 20 years imprisonment or fines exceeding $1 million for aggravated cases.[22] Similarly, 18 U.S.C. § 1343 (wire fraud) extends this to electronic communications, encompassing modern scams like phishing or investment frauds that cross state lines, emphasizing the use of interstate wires in furthering the scheme. State laws vary but typically align with common-law fraud elements: a material misrepresentation of fact, knowledge of its falsity, intent to induce reliance, justifiable victim reliance, and resulting damage.[23] Internationally, frameworks like the UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime treat scams as forms of fraud involving cross-border deception, but enforcement relies on domestic fraud codes without uniform "scam" terminology. This absence of precise legal codification for "scam" underscores its role as an informal label, often overlapping with but not synonymous to fraud, as some scams may evade criminal thresholds if lacking provable intent or harm.[21]Historical Evolution

Pre-Modern and Ancient Examples

One of the earliest codified responses to scams appears in the Code of Hammurabi, dating to approximately 1750 BCE in ancient Mesopotamia, which imposed harsh penalties for deceptive trade practices. Laws 104–107 mandated death for merchants employing false scales or measures that defrauded buyers, particularly if the state incurred losses from diluted goods like beer or oil, reflecting an awareness of systematic cheating in barter and commodity exchanges.[24] Similar frauds involved tampering with weights, as evidenced by archaeological finds of rigged stone weights from the period, underscoring causal links between measurement deception and economic harm in pre-monetary societies.[25] In ancient Egypt around 525 BCE, tax collectors manipulated grain measurements to overcharge households and skim profits, exploiting administrative opacity for personal gain; penalties included severe corporal punishments or restitution to deter state-level embezzlement.[25] Greek records from the same era document merchant Hegestratos's attempt to sink his ship off Salamis circa 525 BCE to fraudulently claim bottomry insurance proceeds, a maritime loan repaid only if the vessel arrived safely; his crew thwarted the plot by alerting authorities, highlighting early insurance-related cons reliant on staged disasters.[3] By the Roman Republic, Cicero's Verrine Orations (70 BCE) exposed Governor Gaius Verres's extortionate tax farming in Sicily, where he inflated assessments and pocketed differences through rigged auctions and bribery, amassing wealth equivalent to millions in sesterces while impoverishing provincials.[25] Pre-modern Europe saw widespread relic frauds, where vendors peddled forged saintly remains—such as multiplied foreskins of Jesus or duplicate heads of John the Baptist—to pilgrims, capitalizing on devotional fervor for profit; 12th-century monk Guibert de Nogent lambasted these in De pignoribus sanctorum, noting absurd proliferations like two-headed Baptist relics sold across monasteries.[26] In the 14th century, scholar Nicole Oresme denounced artifacts like the Shroud of Turin as painted forgeries in his treatise De configurationibus qualitatum et motuum, arguing they exploited credulity via artisanal tricks rather than miracles, a critique predating scientific dating.[27] Alchemy in medieval Europe often devolved into scams, with practitioners promising transmutation of base metals into gold to secure patronage from nobility; laws against such fraud emerged by the 14th century in England and France, banning false demonstrations using sleight-of-hand or alloy substitutions.[28] The 13th-century Book of Charlatans by Jamāl al-Dīn ʿAbd al-Raḥīm al-Jawbarī cataloged over 30 deception types in Middle Eastern cities, including fake oculists applying caustic pastes disguised as cures, rigged divination with loaded dice, and illusory "flying" tricks via hidden pulleys, drawn from the author's observations to warn against urban tricksters preying on the gullible.[29] These schemes thrived on asymmetries in knowledge and verification, persisting until empirical scrutiny curbed their prevalence.Industrial Era Confidence Games

The Industrial Era, spanning the late 18th to early 20th centuries, facilitated the rise of confidence games through rapid urbanization, enhanced mobility from railroads and steamships, and economic expansion that fostered interactions among strangers in burgeoning cities. These conditions eroded traditional community-based trust while necessitating reliance on personal assurances in commercial dealings, creating fertile ground for deceivers who exploited emerging social anonymity. The archetype of the "confidence man" emerged prominently in the United States during this period, exemplified by William Thompson, who in 1849 approached well-dressed pedestrians in New York City, engaged them in conversation to build rapport, and then requested they lend him valuables like watches under the guise of mutual confidence, directly inspiring the term "confidence man" as reported in contemporary newspapers.[30][31] One prevalent scheme was the green goods scam, which proliferated in the late 19th-century United States via advertisements in newspapers or letters promising high-quality counterfeit currency—referred to as "green goods" due to the color of U.S. bills—for sale at a fraction of face value. Victims, often rural or naive individuals, would remit genuine money to urban operators, receiving in return either worthless blank paper, low-grade fakes, or nothing at all; this fraud capitalized on the era's postal expansion and industrial printing capabilities, with gangs like those dismantled by authorities in the 1890s netting thousands of dollars before interventions by figures such as Theodore Roosevelt in his role as a police commissioner.[32] Larger-scale confidence operations targeted industrial magnates and tourists, leveraging transatlantic trade and infrastructure booms. In 1885, con artist William McCloundy reportedly swindled a visitor out of $50,000 by convincing him to "purchase" the Brooklyn Bridge under false pretenses of development rights, reflecting how iconic industrial projects became props for exploiting credulity amid real estate speculation. Similarly, in 1893, an impostor posing as a Standard Oil executive defrauded British steel manufacturer Mr. Lamb of significant sums by promising introductions to John D. Rockefeller, preying on the era's oil and steel tycoons' interconnected networks. These schemes underscored causal vulnerabilities: the confidence man's success hinged on victims' greed or ambition, amplified by the era's speculative fervor in railroads, mining, and manufacturing investments.[33] Petty urban cons also adapted to industrial mobility, such as the 1859 antics of A.V. Lamartine, who staged apparent laudanum overdoses in Ohio hotels to solicit sympathy donations totaling $25 in Dayton and $40 in Sandusky, exploiting transient railroad travelers. By the 1880s, distraction-based thefts like the "disappearing act"—where female accomplices shoplifted luxury goods such as laces from Cincinnati stores while diverting clerks—thrived in commercial hubs, with reports from July 1881 highlighting the anonymity of growing metropolises. Such tactics reveal how industrialization's social dislocations, including rural-to-urban migration and class mixing, enabled deceivers to impersonate clergy or brokers, as in the 1888 case of a fake priest stealing diamonds in Washington, D.C., by invoking misplaced religious trust.[34]20th Century to Digital Transition

In the early 20th century, scams increasingly leveraged postal services for mass dissemination, building on industrial-era techniques but scaling through printed circulars and mail fraud. Charles Ponzi's scheme in 1919-1920 exemplifies this shift, promising investors 50% returns in 45 to 90 days via purported arbitrage in international reply coupons, though it operated as a pyramid paying early participants with later inflows; by July 1920, it had attracted over $15 million from 40,000 investors before collapsing, leaving debts exceeding $7 million.[35][36] Similar boiler-room operations and stock manipulations proliferated during the 1920s economic boom, such as the Radio Pool scam, where fraudsters artificially inflated RCA stock prices before dumping shares, exploiting speculative fervor in unregulated markets.[37] Advance-fee frauds, requiring victims to pay upfront for promised large rewards, gained traction mid-century through letters mimicking official correspondence, with Nigerian variants—known as 419 scams after the relevant criminal code section—emerging in the 1980s via mail and telex, targeting Westerners with tales of frozen assets from corrupt officials.[38][39] These analog methods relied on low-cost replication and postal reach but were limited by response times and verification challenges, often yielding modest individual hauls despite high volume. The late 20th-century advent of fax machines accelerated these schemes by enabling faster, pseudo-official communications, but the internet's commercialization in the mid-1990s marked a pivotal transition, replacing physical mail with email for near-instantaneous, global distribution at negligible cost. Nigerian 419 operations migrated en masse to email by the late 1990s, amplifying reach and reported losses into billions annually by the 2000s, as scammers exploited digital anonymity and poor email filtering.[40] Concurrently, phishing emerged around 1995 on AOL platforms, where hackers used fake login prompts and tools like AOHell to steal credentials, with the term "phishing" (a play on "fishing") first documented that year; by 1996, it involved mass instant messages tricking users into revealing passwords, evolving from isolated intrusions to targeted financial attacks by 2003.[41][42] This digital pivot reduced barriers to entry, enabling scriptable automation and broader targeting, while eroding traditional trust cues like verifiable postage.[43]Operational Mechanics

Fundamental Stages of Deception

The operational core of most scams revolves around a sequence of deception stages that progressively erode the victim's skepticism while amplifying their investment, whether emotional, financial, or informational. This framework, derived from ethnographic studies of professional confidence artists in early 20th-century America, emphasizes building false confidence before extraction, distinguishing elaborate cons from impulsive thefts.[44] David W. Maurer's 1940 analysis, based on interviews with over 100 con men, outlines the "big con" as involving seven primary phases: the put-up, the play, the rope, the tale, the convincer, the breakdown, and the send.[45] These stages are adaptable across scam types, from advance-fee frauds to investment schemes, and rely on causal mechanisms like reciprocity and loss aversion rather than overt force.[46] Put-Up and Play: The initial phase entails scouting and preliminarily engaging the victim, or "mark," to assess suitability based on traits like greed, isolation, or credulity. Con artists, often working in teams, observe public behaviors—such as betting habits or financial displays—to select targets unlikely to report losses due to embarrassment.[44] This "put-up" merges into the "play," where casual interaction establishes rapport, mirroring the victim's interests or vulnerabilities to foster subconscious trust; for instance, a scammer might pose as a sympathetic stranger in a bar or online forum, exploiting shared perceived hardships. Empirical accounts from Maurer's informants reveal this stage succeeds by 70-80% through non-verbal cues like mirroring body language, avoiding premature scheme disclosure.[47] Rope and Tale: Once hooked, the "rope" phase employs logic and flattery to deepen commitment, presenting the scam as a low-risk opportunity tailored to the mark's desires, such as quick wealth or romance. This transitions to the "tale," the core narrative fabricating urgency or exclusivity—e.g., insider stock tips or fabricated emergencies in grandparent scams reported by the FBI, where perpetrators claim a relative's arrest requiring wire transfers.[48] Causally, this exploits confirmation bias, as victims selectively interpret ambiguous signals as validation; a 2015 study on romance scams documented groomers sustaining this via daily affirmations, escalating from platitudes to promises over weeks.[49] Convincer and Breakdown: To dispel doubts, the "convincer" delivers a controlled "win," such as a small payout or verifiable "proof" like staged testimonials, reinforcing the illusion of legitimacy and triggering sunk-cost escalation. In Maurer's wire scam variant, marks receive falsified racing tips yielding minor gains, priming them for larger bets.[44] The "breakdown" follows, extracting the bulk via high-pressure demands framed as final steps, often involving accomplices to simulate authenticity; FTC data from 2023 shows investment cons averaging $7,000 losses here, with victims transferring funds under false deadlines.[50] Send: Concluding deception, the "send" ejects the mark with excuses like logistical delays, ensuring they depart without immediate confrontation while con artists disperse to evade traceability. Maurer's cases note marks often rationalize losses as bad luck, with only 10-20% pursuing authorities due to self-blame.[51] This phase underscores scams' reliance on post-exploitation silence, as psychological denial perpetuates the con's ecosystem; modern adaptations, like cryptocurrency "pig butchering" schemes, extend it digitally by ghosting after wallet drains, per FinCEN alerts analyzing $ billions in annual U.S. losses.[50]Adaptations in Complex Schemes

In complex scam schemes, perpetrators extend the fundamental stages of deception—such as initial contact, trust-building, and extraction—through multi-layered operations that incorporate reconnaissance, technological augmentation, and organizational division of labor to enhance scalability, reduce traceability, and prolong victim engagement. These adaptations often involve specialized roles within syndicates, where individuals handle discrete tasks like data gathering, communication, or fund laundering, minimizing individual risk exposure. For instance, business email compromise (BEC) schemes typically begin with extensive reconnaissance to identify high-value targets and their hierarchies, followed by spear-phishing to gain email access, account takeover via credential theft or malware, and impersonation to authorize fraudulent wire transfers, resulting in global losses exceeding $2.7 billion in 2022 alone as reported by the FBI.[52][53] Technological integrations further evolve these mechanics, enabling real-time adaptation to defenses. In authorized push payment (APP) fraud, scammers leverage stolen personal data from breaches—such as hotel loyalty programs—to profile victims, initiate urgency-driven phishing (e.g., alerting to a "detected fraud"), deploy AI-generated deepfake voices or texts for impersonating bank officials, and guide victims to self-initiate transfers to mule accounts, bypassing traditional transaction flags. This multi-stage approach exploits psychological pressure alongside tools like voice cloning software, contributing to annual global losses in the billions, with the UK's APP scams alone costing £485 million in 2023.[54] Transnational adaptations amplify complexity by exploiting jurisdictional gaps and digital anonymity. Job scams, for example, recruit victims via social media with promises of high-yield remote work, extract upfront "fees" or data, then layer proceeds through high-velocity micro-transactions across cryptocurrencies, digital wallets, and banks in permissive regions, complicating law enforcement. A 2023-2024 syndicate targeting Singaporeans defrauded over 3,000 victims of $45.7 million before arrests in March 2024 highlighted this model's efficiency, with operations spanning Malaysia and using mules for fund dispersion.[55][56] Such schemes evolve by incorporating feedback loops from dark web forums, where tactics like AI chatbots for sustained victim interaction replace static scripts, sustaining yields amid increasing platform scrutiny.[57]Categories of Scams

Interpersonal and Advance-Fee Scams

Interpersonal scams involve direct or simulated personal engagement to establish trust, often culminating in requests for upfront payments characteristic of advance-fee schemes. These frauds exploit emotional bonds or fabricated relationships, inducing victims to send money for promised benefits that fail to materialize. Advance-fee scams specifically require victims to pay fees—such as processing, legal, or tax costs—to access larger sums, prizes, or services.[58][59] A prominent example is the 419 scam, named after section 419 of the Nigerian Criminal Code, where perpetrators pose as officials or heirs offering shares in fortunes, oil deals, or contracts in exchange for advance fees to cover alleged bureaucratic hurdles. Originating in the 1980s via letters and faxes, these evolved to email by the 1990s, with scammers often operating from West Africa. Victims have lost billions globally, though exact figures remain elusive due to underreporting.[58][60] Romance scams represent a modern interpersonal variant, where fraudsters create fake profiles on dating sites or social media to cultivate affection before soliciting funds for emergencies, travel, or investments. Scammers frequently claim to be deployed military personnel, widowed professionals, or stranded travelers, using scripted narratives to evoke sympathy. In 2023, U.S. consumers reported $1.14 billion in losses to such schemes, with a median loss of $2,000 per victim—the highest among scam categories tracked by the Federal Trade Commission. Losses escalated further in 2024, exceeding $1.3 billion amid rising online interactions.[61][48][62] Other advance-fee interpersonal tactics include job offer scams demanding fees for training or equipment, and lottery or prize notifications requiring payment to claim winnings. These schemes thrive on urgency and secrecy, warning victims against disclosure to "protect" the deal. The FBI classifies them under confidence frauds, noting organized networks use money mules and cryptocurrency for laundering. Reported U.S. losses to confidence scams, encompassing these types, reached $652 million in 2023 per FBI estimates, though actual totals likely exceed this due to unreported cases.[58][63]Investment and Pyramid Structures

Investment scams typically involve promoters enticing victims with promises of high returns on purported investments, such as stocks, cryptocurrencies, or fictitious assets, often with assurances of low risk or guaranteed profits that defy market realities. These schemes rely on influxes of new capital to sustain payouts to earlier participants, creating an illusion of legitimacy until recruitment falters. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) classify such frauds as violations of securities laws, emphasizing that legitimate investments carry inherent risks and no assured gains.[5][64] Pyramid schemes, a subset of investment fraud, operate on a recruitment-driven model where participants are compensated primarily from fees paid by new recruits rather than from product sales or genuine profits. Each participant must enlist additional members to advance levels and receive payouts, forming an inverted pyramid that demands exponential growth—typically doubling recruits per level—which becomes mathematically impossible after a few tiers due to finite population limits. The FTC deems pure pyramid schemes illegal under Section 5 of the FTC Act, as they generate no underlying value and inevitably collapse, leaving most participants as net losers.[65] In contrast, Ponzi schemes centralize control under a single operator who fabricates investment performance, using funds from new investors to pay "returns" to earlier ones without engaging in actual trading or business activity. Named after Charles Ponzi's 1920 postal coupon arbitrage fraud, which promised 50% returns in 45 days but paid out with fresh deposits, these differ from pyramids by lacking overt multi-level recruitment; instead, they mimic legitimate funds through falsified statements. Bernie Madoff's operation, exposed on December 11, 2008, exemplifies this: it defrauded investors of approximately $65 billion over decades by reporting steady 10-12% annual gains via a nonexistent "split-strike conversion" strategy, collapsing amid the financial crisis when redemption requests surged.[66][67] Both structures exploit the same causal dynamic: sustainability hinges on continuous inflows exceeding outflows, but real-world constraints like market saturation or regulatory scrutiny trigger insolvency, with losses concentrated on late entrants. In 2024, U.S. consumers reported over $12.5 billion in total fraud losses, with investment scams—including Ponzi and pyramid variants—driving the sharpest increases, often amplified by digital platforms promising crypto or forex windfalls. Regulators note that while multi-level marketing (MLM) programs may superficially resemble pyramids, they skirt illegality by tying compensation to verifiable retail sales, though FTC actions against deceptive MLMs highlight blurred lines when recruitment dominates.[5][68]Digital and Technological Exploits

Phishing and spoofing represent the most reported form of digital scam, involving fraudulent attempts to obtain sensitive information such as login credentials or financial data through deceptive emails, websites, or messages mimicking legitimate entities. In 2024, the FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) received over 193,000 complaints for phishing/spoofing, making it the top cybercrime category by volume.[69] These scams often employ urgency or fear tactics, such as alerts about account compromises, leading victims to click malicious links or provide details directly. Losses from such schemes contribute significantly to the overall $16.6 billion in reported internet crime damages that year.[70] Ransomware attacks, a technological exploit where malware encrypts victim data and demands payment for decryption keys, targeted businesses and individuals with increasing sophistication in 2024. Perpetrators typically gain entry via phishing emails or exploited software vulnerabilities, then exfiltrate data for leverage in double-extortion tactics. The FBI IC3 noted ransomware as a persistent threat, with email serving as the primary vector in many cases, though specific complaint volumes were bundled under broader extortion categories exceeding 86,000 reports.[69][71] Global analyses indicate ransomware incidents drove portions of the $16.6 billion U.S. losses, often amplified by affiliates distributing malware through dark web markets.[72] Cryptocurrency scams exploit blockchain's pseudonymity and hype around digital assets, including investment frauds, fake exchanges, and wallet drainers that steal funds via phishing or malicious smart contracts. The FBI reported nearly 150,000 complaints involving digital assets in 2024, with losses totaling $9.3 billion—a 66% increase from prior years—fueled by schemes like pig butchering operations blending romance scams with crypto promises.[73] Hacks and scams extracted approximately $2.2 billion in crypto funds globally, with notable incidents such as the $300 million theft from a single DeFi protocol.[74] FTC data corroborates high stakes, with investment scams overall causing $5.7 billion in U.S. losses, many tied to crypto pitches via social media or apps.[7] Business email compromise (BEC) schemes use compromised or spoofed executive accounts to authorize fraudulent wire transfers, leveraging digital communication tools for impersonation. These technologically enabled frauds resulted in substantial portions of the FBI's reported losses, often exceeding millions per incident due to rapid fund movement.[69] Tech support scams, where fraudsters pose as IT help via pop-ups or calls to gain remote access and extract payments, saw U.S. losses rise to $1.464 billion in 2024, an 87% increase since 2022, frequently targeting seniors through malware-laden downloads.[75] Emerging exploits incorporate AI, such as voice cloning for impersonation in phone scams or deepfakes in video calls to build false trust, amplifying traditional deceptions with synthetic media. NatWest analysis identified AI voice cloning among the fastest-growing scams in 2024, with 42% of surveyed victims encountering advanced tech variants.[76] FTC reports highlight online-initiated scams causing over $3 billion in losses, underscoring the shift to digital platforms where verification lags behind technological manipulation.[77] These methods succeed by exploiting trust in familiar interfaces, with total U.S. fraud losses reaching $12.5 billion per FTC Sentinel data.[7]Human Vulnerabilities

Psychological Mechanisms and Biases

Scammers exploit inherent cognitive shortcuts and heuristics that evolved for efficient decision-making in ancestral environments but falter under deceptive pressures, leading victims to override rational scrutiny. Dual-process theory posits that human cognition operates via System 1 (fast, automatic, emotion-driven) and System 2 (slow, deliberate, analytical); fraudsters target System 1 by inducing urgency, emotional arousal, or familiarity, suppressing analytical verification.[78] A 2022 study on scam compliance identified core influences including psychological traits like impulsivity and cognitive overload, where victims' motivation—often greed or fear—amplifies heuristic reliance, with empirical data from grounded theory analysis revealing these factors in over 80% of reported cases.[79] Authority bias, the undue deference to perceived experts or officials, facilitates compliance in impersonation scams, as individuals subconsciously yield to symbols of power without evidence assessment; research on phishing susceptibility confirms this bias elevates victimization risk by 25-40% in simulated trials.[80] Scarcity and urgency heuristics compound this, prompting impulsive actions under fabricated time constraints, such as "limited investment windows," which empirical experiments demonstrate reduce detection rates by triggering loss aversion over gain evaluation.[81] Social proof bias further entrenches vulnerability, where scammers invoke fabricated testimonials or peer participation to normalize deceit, aligning with conformity pressures observed in group deception studies where compliance rises with perceived consensus.[82] Overconfidence bias, particularly in self-assessed deception detection, heightens susceptibility across demographics, with well-educated victims paradoxically more prone due to illusory superior judgment; a review of romance scam victims linked this to higher scam engagement rates among overconfident profiles.[83] Negativity bias amplifies fear-based tactics, rendering threat-laden messages—like account compromise alerts—more persuasive than neutral ones, as negativity draws disproportionate cognitive resources, evidenced by victimization models showing fear appeals increase response likelihood by up to 50%.[84] Confirmation bias sustains ongoing deception by selectively interpreting ambiguous cues as validating initial trust, perpetuating schemes like pyramid investments where early minor gains reinforce flawed beliefs despite mounting inconsistencies.[85] These mechanisms, while adaptive in low-stakes contexts, causally underpin fraud success by systematically distorting probabilistic reasoning, with meta-analyses affirming their role in 70-90% of analyzed victim narratives.[86]Demographic and Behavioral Risk Factors

Certain demographic characteristics correlate with elevated risk of scam victimization. Older adults, particularly those aged 60 and above, experience disproportionately high financial losses from fraud, with median losses per victim exceeding those of younger groups; for instance, in FTC-reported data analyzed by AARP, individuals over 60 accounted for a significant share of total scam losses despite comprising fewer reports overall.[87] This vulnerability stems from factors such as age-related cognitive declines, which impair scam detection, as evidenced in cohort studies of community-dwelling seniors without dementia.[88] Lower education levels and reduced financial literacy further amplify risk across age groups, with individuals possessing less formal education showing higher susceptibility due to diminished ability to evaluate complex financial propositions.[89] Income levels present a mixed pattern: higher-income individuals are targeted more frequently in investment scams, while lower-income groups face elevated rates in advance-fee schemes, though overall victimization does not strictly align with socioeconomic status.[90] Gender differences in scam susceptibility are inconsistent across studies, with some indicating no significant disparity, while others note men overrepresented in high-stakes investment frauds and women in relational or grandparent scams, potentially reflecting targeting strategies rather than inherent traits.[91] Ethnic and regional variations also emerge; for example, research in diverse populations highlights higher victimization among certain minority groups due to intersecting factors like language barriers or community-specific targeting, though causal links require controlling for confounders such as urban density.[92] Behavioral risk factors often interact with demographics to heighten exposure. Loneliness and social isolation substantially increase scam susceptibility, as isolated individuals exhibit greater responsiveness to fraudulent overtures promising companionship or validation, with longitudinal data linking low social support to repeated victimization.[93] Personality traits like high agreeableness—characterized by reluctance to confront or distrust others—predict higher fraud rates, as agreeable individuals are less likely to scrutinize suspicious claims.[94] Risky health behaviors, including excessive alcohol consumption, recreational drug use, and smoking, correlate with fraud exposure, potentially through impaired judgment or associations with high-risk social networks.[90] Low scam awareness and routine online behaviors further contribute; adults engaging in frequent digital interactions without prior exposure to common fraud tactics, such as phishing simulations, demonstrate heightened vulnerability, independent of age.[95] Impulsivity and over-optimism, measurable via validated scales, drive decisions to bypass verification in urgent-seeming schemes, while poor financial decision-making habits—such as chasing high-return promises—exacerbate losses in pyramid or investment frauds.[96] These factors underscore that behavioral interventions targeting skepticism and verification routines can mitigate risks more effectively than demographic profiling alone.[91]Societal and Economic Consequences

Quantified Financial Damages

In 2023, global financial losses from scams and related frauds were estimated at over $1 trillion, with scammers siphoning away more than $1.03 trillion in the subsequent 12 months ending October 2024, according to the Global Anti-Scam Alliance's analysis of reported incidents across 190 countries.[97] Interpol corroborated this scale, reporting that scammers stole over $1 trillion from victims worldwide in 2023 alone, driven by the proliferation of cyber-enabled schemes targeting individuals and businesses.[98] More conservative projections from Nasdaq Verafin pegged direct fraud and scam losses at $485.6 billion for 2023, encompassing consumer-targeted scams ($40 billion) and broader bank fraud ($450 billion), highlighting variances in estimation methodologies that often exclude unreported cases.[99] These figures underscore systemic underreporting, as victims frequently withhold details due to embarrassment or lack of awareness, implying actual damages substantially exceed documented totals.[69] In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission's Consumer Sentinel Network documented $10 billion in fraud losses for 2023, with investment scams accounting for $4.6 billion—the largest category, reflecting a 21% year-over-year increase—and imposter scams contributing $2.7 billion.[100] [101] Losses escalated to $12.5 billion in 2024, a 25% rise, with investment fraud surging to $5.7 billion amid heightened cryptocurrency-related deceptions.[5] Complementing this, the FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) reported $12.5 billion in verified internet crime losses for 2023, predominantly from scams like business email compromise ($2.9 billion) and investment fraud, before climbing 33% to $16.6 billion in 2024, where cryptocurrency investment scams alone caused over $6.5 billion in damages.[70] [69]| Year | FTC Fraud Losses (USD) | Key Category Breakdown | FBI IC3 Internet Crime Losses (USD) | Key Category Breakdown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | $10 billion | Investment: $4.6B; Imposter: $2.7B | $12.5 billion | BEC: $2.9B; Investment: significant portion |

| 2024 | $12.5 billion | Investment: $5.7B | $16.6 billion | Crypto investment: $6.5B |

Non-Monetary and Systemic Effects

Scams inflict profound psychological harm on victims beyond financial losses, manifesting as depression, anxiety, shame, embarrassment, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A 2025 analysis of internet scams documented severe emotional distress among victims, with romance scam sufferers experiencing prolonged trauma, social isolation, and heightened vulnerability to further exploitation due to eroded self-esteem.[104] Empirical studies corroborate these effects, linking fraud victimization to elevated depressive symptoms, particularly among middle-aged and elderly individuals, where experiences of being defrauded correlate with persistent mental health declines.[105] Surveys of scam victims reveal that 69% report negative mental health impacts, including stress and sleep disturbances, while 44% experience clinical-level anxiety, often exacerbating pre-existing conditions.[106][107] These individual traumas extend to relational and social disruptions, straining family ties and fostering interpersonal distrust. Victims frequently describe feelings of betrayal leading to isolation, with identity theft cases associated with anger, relational conflicts, and withdrawal from social networks.[108] In severe instances, such distress contributes to suicidal ideation, as evidenced by qualitative accounts of emotional exhaustion and guilt persisting post-victimization.[109] Among seniors, a global survey of 3,000 affected individuals highlighted widespread emotional fallout, including diminished confidence in personal judgment, which perpetuates cycles of vulnerability.[110] Systemically, scams erode public trust in institutions, digital platforms, and societal norms, compromising the interpersonal confidence necessary for economic and social functioning. Government imposter schemes, for instance, foster skepticism toward official communications, reducing compliance with legitimate services and amplifying broader cynicism.[111] This trust deficit hinders digital payment adoption, as victims' experiences propagate caution that stifles innovation and transaction efficiency.[112] On a societal scale, pervasive fraud undermines faith in state entities, exacerbating governance challenges and diverting resources toward verification protocols that may infringe on privacy without fully restoring confidence.[113] Such dynamics foster a feedback loop of suspicion, where repeated betrayals normalize guarded interactions, potentially weakening community cohesion and institutional legitimacy over time.[114][115]Countermeasures and Responses

Personal Vigilance and Verification

Individuals can enhance personal vigilance by adopting a deliberate pause before responding to unsolicited offers or requests, as hasty decisions under pressure exploit cognitive biases like scarcity and urgency, which scammers frequently manipulate.[116][117] Research on scam prevention indicates that slowing down allows time for rational evaluation, reducing susceptibility; for instance, FTC studies show that victims who consulted others prior to acting were less likely to incur losses.[118][119] Verification entails independently confirming identities and claims through official channels rather than relying on contact details provided by the solicitor. For example, if an entity claims affiliation with a bank or government agency, individuals should terminate the interaction and initiate contact using verified numbers from official websites or directories, a method recommended by the FTC to circumvent impersonation tactics prevalent in 2024 scam reports.[120][121] Tools such as domain lookup services (e.g., WHOIS) can reveal website registration discrepancies, while reverse image searches detect stolen photos in romance or investment frauds, with Consumer Reports noting these steps thwarted potential losses in tested scenarios.[122] Key verification practices include scrutinizing for inconsistencies in communication, such as poor grammar, generic greetings, or evasion of direct questions, which signal non-legitimate sources per FTC guidelines.[123] Enabling multi-factor authentication on accounts and monitoring credit reports via free annual services from agencies like Equifax add layers of protection, as fraud alerts can block unauthorized credit inquiries—a proactive measure that prevented identity theft in numerous documented cases.[124]- Assess emotional triggers: Recognize appeals to fear, greed, or authority, which psychological analyses identify as core scam tactics; pausing to question motives disrupts manipulation.[117][125]

- Limit information sharing: Withhold personal or financial details until identity is confirmed, as scammers exploit shared data for further targeting.[10]

- Cross-reference claims: Search public records or regulatory databases (e.g., SEC for investments) for legitimacy, avoiding unverified promises of high returns.[116]

Regulatory and Technological Interventions

In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) enforces consumer protection laws by pursuing legal actions against fraudulent schemes, including lawsuits against operators of tax debt relief scams that impersonate government entities and make false threats to consumers.[126] The FTC has also issued warning letters to companies engaging in potentially unlawful practices and maintains ongoing enforcement against scams targeting vulnerable groups, such as older Americans, where impersonation and sophisticated tactics have increased in prevalence as of October 2025.[127][128] The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) complements these efforts by addressing investment-related fraud through whistleblower programs and notices of covered actions that recover assets from illicit schemes.[129] In the European Union, regulatory frameworks like the proposed Payment Services Directive 3 (PSD3) and Payment Services Regulation (PSR) aim to enhance security against impersonation fraud and authorized push payment scams by mandating stronger authentication and liability shifts for payment service providers.[130] The Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), effective from 2025, requires financial institutions to bolster cybersecurity and operational resilience to mitigate fraud risks in digital transactions.[131] EU anti-fraud strategies vary by member state but emphasize coordinated measures against cross-border financial crimes, with all states reporting dedicated plans as of 2025.[132] Internationally, organizations like the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), INTERPOL, and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) promote cooperation through initiatives such as the 2025 Handbook on International Co-operation against Money Laundering, which provides tools for detecting and prosecuting scams linked to illicit flows from fraud, drug trafficking, and human smuggling.[133][134] FATF standards focus on asset recovery to deprive scammers of proceeds, with partnerships like FATF-INTERPOL targeting trillions in illicit profits through enhanced global information sharing and enforcement.[135][136] Technological interventions increasingly rely on artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for real-time fraud detection, with tools like behavioral biometrics analyzing user patterns to identify anomalies in transactions and interactions.[137] Solutions from providers such as BioCatch and Feedzai employ cognitive science and AI models to detect scams, including authorized push payments and document fraud, achieving deployment in 50% of banking operations for scam prevention by mid-2025.[138][139] Platforms like ClearSale and Resistant AI integrate machine learning to flag suspicious orders and scams, reducing false positives through adaptive algorithms trained on vast datasets of fraudulent behaviors.[140][141] Emerging uses of large language models and retrieval-augmented generation assist in proactive scam identification, countering AI-enhanced fraud tactics observed in 2025 trends.[142] These technologies emphasize continuous monitoring of behavioral and transactional data, though their efficacy depends on integration with regulatory compliance to address evolving threats like generative AI-driven impersonations.[143]Contemporary Developments

Rise of AI-Enabled Fraud

The advent of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has significantly lowered the technical and financial barriers for fraudsters, enabling the creation of highly convincing impersonations and automated deception at scale. Tools like voice cloning software, which can replicate a person's speech from mere seconds of audio, and deepfake video generators have transformed traditional scams such as business email compromise (BEC) and vishing (voice phishing) into more persuasive variants. For instance, in February 2024, a Hong Kong-based finance worker transferred $25 million to scammers after a video conference call featuring deepfake representations of the company's chief financial officer and other executives, all generated using publicly available images and AI synthesis.[144] Similarly, AI-driven voice cloning has facilitated family emergency scams, where fraudsters mimic relatives' voices to solicit urgent funds, with attacks escalating as models require only 15 seconds of target audio for replication.[145] Reports of generative AI-enabled scams increased by 456% year-over-year as of May 2025, driven by deepfakes and autonomous AI agents that handle entire scam interactions.[146] Phishing incidents surged 466% in the first quarter of 2025, fueled by AI-generated kits that produce personalized, grammatically flawless lures, while breached personal data volumes rose 186% amid automated exploitation.[147] Deepfake fraud cases in North America jumped 1,740% from 2022 to 2023, with global financial losses from such schemes nearing $900 million by mid-2025, split roughly 40% for businesses and 60% for individuals.[148][149] Vishing attacks, amplified by AI deepfakes, increased 442% in 2025 alone, contributing to an estimated $40 billion in worldwide fraud losses.[150] The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) highlighted generative AI's role in facilitating social engineering and financial fraud in a December 2024 public service announcement, noting its use in crafting believable text for spear-phishing and BEC schemes.[151] Overall fraud losses reported to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reached $12.5 billion in 2024, a 25% rise from the prior year, with AI enhancements cited as a key accelerator in internet crime trends.[5] Projections indicate U.S. AI-driven scam losses could hit $40 billion annually by the late 2020s, as fraudsters leverage accessible platforms to scale operations beyond manual capabilities.[152] Financial institutions, the most targeted sector, average over $600,000 in losses per deepfake incident.[153] These developments underscore AI's dual-edged nature, where rapid democratization of synthetic media outpaces detection technologies.Global Trends and Statistics Post-2023

Global scam losses exceeded $1 trillion in the 12 months leading up to late 2024, according to the Global Anti-Scam Alliance (GASA) and Feedzai's joint report surveying 58,329 consumers across multiple countries.[97] [154] This figure encompasses various fraud types, with authorized push payment (APP) scams alone contributing over $1.026 trillion globally from August 2022 to August 2023, a trend persisting into 2024 amid rising digital transaction volumes.[155] Recovery rates remain dismal, with only 4% of victims regaining their full losses, highlighting systemic underreporting and enforcement gaps.[154] Prevalence has intensified, with nearly 50% of global consumers facing at least one attempted scam weekly in 2024, per GASA data cited in partnerships with cybersecurity firms.[156] Victimization rates doubled in the United States to 62% by mid-2025, while reaching 90% in high-exposure regions like Vietnam, according to F-Secure's Scam Intelligence Report analyzing surveys from multiple nations.[157] Shopping scams affected 22% of respondents in the GASA-Feedzai study, marking the most common variant, followed by rapid-executing tactics where nearly half of incidents conclude within 24 hours of contact.[154] Email-based scams proved most successful at 11%, with younger adults (18-34) facing over twice the risk compared to seniors, driven by social media and AI-enhanced phishing.[157] Fraud industrialization emerged as a dominant trend, with 96% of over 1,200 fraud professionals across the US, Europe, and Asia-Pacific expressing concern over cross-border, sophisticated attacks breaching sectors.[158] Generative AI exacerbated this, enabling deepfakes and synthetic identities that may account for 20% of certain credit losses, prompting 75% of US businesses to rank AI-driven cybercrime as a top challenge.[155] Only 7% of scams are reported globally, attributed to emotional distress surpassing financial harm and victim-blaming stigma, per F-Secure analysis.[157] Regional variations show Southeast Asia with 63% exposure rates and the UK losing £11.4 billion ($14.4 billion) annually, underscoring uneven regulatory impacts.[159] [160]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/scam