Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Joe Pullen

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series on |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

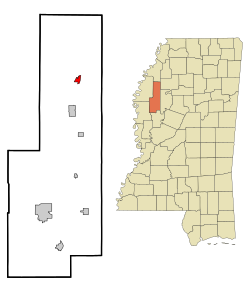

Joe Pullum (c. 1883 – December 15, 1923) was an African-American sharecropper who was lynched by a posse of local white citizens near Drew, Mississippi on December 15, 1923.

While the circumstances that precipitated the violence were typical for that place and time, Pullum's case was unusual in that he managed to kill at least two members of the posse and wound several others before ultimately perishing himself. As such, Pullum became a folk hero to the local black population and was championed by the Universal Negro Improvement Association.

Background

[edit]Reports of lynchings in the American South had been on the rise since the end of World War I, which may have reflected an increase in the number of incidents.[1] Over the course of the previous decade, eighty-six people had been lynched within the state of Mississippi alone (eighty-three black men, two white men, and one black woman).[2] The rate varied by season, with fewer lynchings during the October and November harvest season when labor was at a premium, and a greater number once the harvest had been brought in and the process of "settling up" between plantation owner and sharecropper began.[3] Up to this point there had been a handful of lynchings nationwide that had met with resistance, but the efforts to fight back were spontaneous, unorganized and solitary.[4] While the lynching of Joe Pullum is considered one of the "most dynamic"[4] cases of resistance, the event was typical in many respects: a dispute between a tenant and landlord in December resulting in ad hoc defense by the victim alone.

Incident

[edit]The details of the lynching are disputed,[a] but both contemporary records and recent scholarly research are consistent as to the broad outlines. Joe Pullum, a tenant farmer, disputed a debt owed to his landlord W. T. Saunders.[b] Pullen shot and killed Saunders and then, after collecting an additional firearm and ammunition, fled into the countryside. A mob formed and pursued Pullum, intending to capture him. Pullum managed to kill and wound several members of the mob before he was himself killed. The details surrounding the nature of the disagreement, who fired first, the size of the mob, the particulars of the manhunt, and the numbers of casualties, vary significantly.

Contemporary newspaper accounts

[edit]The story made Associated Press newswire and was republished in many newspapers. The newswire story mentions the initial confrontation occurring just after noon on December 14. W.T. Saunders died with a bullet through his heart. Pullen then grabbed a shotgun along with his .38-caliber revolver and fled to swamps 3 miles away. Throughout the day, he was spotted by the posse formed, but was able to shoot at them and get away. He shot eleven members of the posse. A twelfth member was injured during setting up a machine gun. Pullum entrenched himself in a drainage ditch. The event ended at 1 a.m. on December 15 after the posse started a fire in the drainage ditch with members capturing him. The story suggested he was barely alive but died soon.[7][6][5]

The story lists wounded and killed members of the posse:

- R. L. Methevin and William J. Hess died.

- J. L. (Bud) Doggett, a prominent lumber man and sportsman from Clarksdale, Mississippi was shot near the heart, seriously wounded but expected to live.

- A. L. Manning and Kenneth Blackwood were shot in the face and neck. Both weren't expected to survive. A. L. Manning died on December 16.

- Luther Hughes, C. A. Hammond, Bob Stringfellow, J. B. Ratlieff, B. A. Williams, Robert Kirsch were listed as wounded.

Recent scholarship

[edit]Nick Salvatore's account from interviewing people who previously lived in Drew says Pullum was a sharecropper who had a dispute with Sanders over the amount owed on settlement day and refused to give permission for Pullum to leave. Some say Sanders shot Pullen first, but Pullum got a .38-caliber revolver and shot and killed Sanders. He then ran to the swamps east of the plantation with 75 rounds of ammunition. A posse of 1000 men formed to capture him, including the sheriff of Clarksdale and the department machine gun. Pullum's knowledge of the terrain and sharpshooting skills helped him.[9]

Terrance Finnegan's account pointed out such incidents were common in the area, especially in December at settlement time, when money was paid for crops. Such events most commonly happened with tenant-landlord relationships. In his account, Sanders was mad because Pullum used money to fix his house and purchase necessities. Pullum believed the money was his to pay for work previously done but wasn't paid for. Sanders went to Pullum's house with J. D. Manning. When Sanders demanded the money of $50, Pullum pulled out a .38 revolver and shot and killed Sanders. He then ran to the bayou as Manning got a sheriff posse. When the posse arrived, Pullum started shooting, hitting three of them. The posse then started shooting at him, and when that didn't work, got some gasoline and set the ditch he was in on fire. In the meantime, some others from the posse got a machine gun and automatic rifles from Clarksdale. When they came back, they set up and started shooting again. The gunfight lasted for an hour. When Pullum fled from the ditch, the machine gun shot him several times, seriously wounding him. The posse members then tied him to a car and dragged him to Drew. His ear was cut off, put into alcohol, and showed in a store display after that. Newspapers claimed he killed 5 people and wounded 9, but local Black residents claim he killed 13 and wounded 26.[3]

Elizabeth Woodruff's account mentions Pullum ambushing the posse members, shooting one in the face, killing him, one in the head, and another on the side. The posse members used 8 to 10 boxes of shells, with none of them hitting him. They used three gallons of gas to pour into the ditch before they got him out. They used a Browning machine gun and two automatic rifles, shooting Pullum when he ran out.[1]

Akinyele Omowale Umoja's account says the dispute was over $50. Sanders went to confront Pullum, and feeling insulted Pullum kept his hands in his pockets, an act of disrespect. Sanders ordered Pullum to remove his hands, and when Pullum did, he pulled out a revolver and shot Sanders. Pullen obtained the shotgun and more ammunition from his mother's house. The mob numbered 100. This account said Pullum killed 9 and wounded 9 in a battle that lasted 7 hours. The mob members dragged the body as a lesson to the local Black population. They showed off Pullum's shotgun, treating it as a battle trophy.[4]

Recollections of Fannie Lou Hamer

[edit]Civil rights pioneer Fannie Lou Hamer was 8 years old at the time. In her retelling of the events, "Pulliam" (her words) did a lot of work for Saunders but was never paid for it. Saunders gave him $150 to get people to work on his plantation, but Pullum kept the money to make up for unpaid work. After a while, Saunders noticed Pullum didn't bring anybody to work for him. Saunders went to confront Pullum, carrying a rifle with him, with J. D. Manning staying in the buggy. Saunders shot Pullum in the arm once, then Pullum shot Saunders with a Winchester rifle. Manning went to town to get the posse. Pullen then hid in Powers Bayou (the swamp) in a hollow tree. He would shoot at the posse when he had the chance. In her version (likely the version circulated around African-Americans in the area), he killed 13 and wounded 26. After the posse poured gasoline then set fire to the swamp and burned the tree he was in, he crawled out, but was found unconscious. The posse members dragged him to town to display him to the Negroes. They cut his ear off and it was displayed in a storefront window in Drew for a long time. In her words, though, "... it was awhile in Mississippi before the whites tried something like that again."[8][10]

Aftermath

[edit]Afterwards, Drew and nearby towns began enforcing curfews against blacks more strictly. In 1924, a Drew sheriff killed 7 or 8 black citizens in one incident for being on the streets past curfew.[4] Many blacks responded by leaving the area, due to Jim Crow laws, institutionalized racism, and higher wages available in the north.[1][9] However, violence between planters and tenants went down.[3]

For blacks who learned of the shootings and Pullum's lynching, especially those who were attracted to the militant Marcus Garvey organization (the Universal Negro Improvement Association or UNIA), Pullum was a hero who, as the newspaper of the UNIA proclaimed, "should have a monument."[11] The UNIA felt the only way to end lynching was with force, by mobilizing blacks in the south.[4]

See also

[edit]- Lynching in the United States

- Sharecropping in the United States

- Jim Crow laws

- Emmett Till, a more widely known lynching, also taking place in Drew, Mississippi

Notes

[edit]- ^ While all accounts agree on the large number of people participating in the lynching, there is no consistent term to describe that group. Contemporary newspaper accounts used the term posse uniformly.[5][6][7] Hamer's autobiographical account uses lynch mob.[8] Recent historians have used both mob[4][3] and posse.[1][9]

- ^ "Saunders" is sometimes rendered as "Sanders".

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth (2003), American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta, Harvard University Press, p. 138, ISBN 9780674010475

- ^ Mills, Kay (1993), This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fanny Lou Hamer, New York, NY: Dutton, pp. 11–12, ISBN 9780525935018

- ^ a b c d Finnegan, Terrance (February 11, 2013), A Deed So Accursed: Lynching in Mississippi and South Carolina, 1881–1940, University of Virginia Press, ISBN 9780813933856

- ^ a b c d e f Umoja, Akinyele Omowale (2003), We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement, New York University Press, ISBN 9780814725245

- ^ a b Machine Gun Used in Hunting Down Negro Murder, Providence, RI: Evening Tribune, December 15, 1923, p. 1

- ^ a b Terrible results of battle with lone negro farmer, Easton, PA: Easton Daily Free Press, December 15, 1923, p. 3

- ^ a b Negro Murderer Was Killed, vol. 4, Nevada, MI: The Nevada Daily Mail and Evening Post, December 15, 1923, p. 1

- ^ a b Hamer, Fannie Lou (1986). "To Praise Our Bridges". In Abbott, Dorothy (ed.). Mississippi Writers: Reflections of Childhood and Youth Volume II: Nonfiction. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9780878052349.

- ^ a b c Salvatore, Nick (October 15, 2007). Singing in a Strange Land: C. L. Franklin, the Black Church, and the Transformation of America. Hachette Digital, Inc. ISBN 9780316030779. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ Hamer, Fanny Lou (1967), Lester, Julius; Varela, Mary (eds.), To Praise our Bridges: an Autobiography, Jackson, MS: KIPCO, pp. 322–323, OCLC 67248381; quoted in Mills, pg. 11–12.

- ^ Negro World, January 19, 1924, page 2; cited in Umoja, 20.

Further reading

[edit]- Philip Dray, At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America (New York: Modern Library, 2003).

- Akinyele Omowale Umoja, We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement (New York: NYU Press, 2013), pp. 19–20.

- M. Susan Klopfer, "Emmett Till Blog" (accessed June 16, 2013). See Kay Mills, This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer(Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2007), pp. 11–12. Pullen's name is spelled "Pullum" in this account.

- Amy Louise Wood, Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

- Rolinson, Mary (February 2012). Grassroots Garveyism: The Universal Negro Improvement Association in the Rural South, 1920-1927. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807872789. Retrieved July 6, 2013.