Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Insect mouthparts

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2023) |

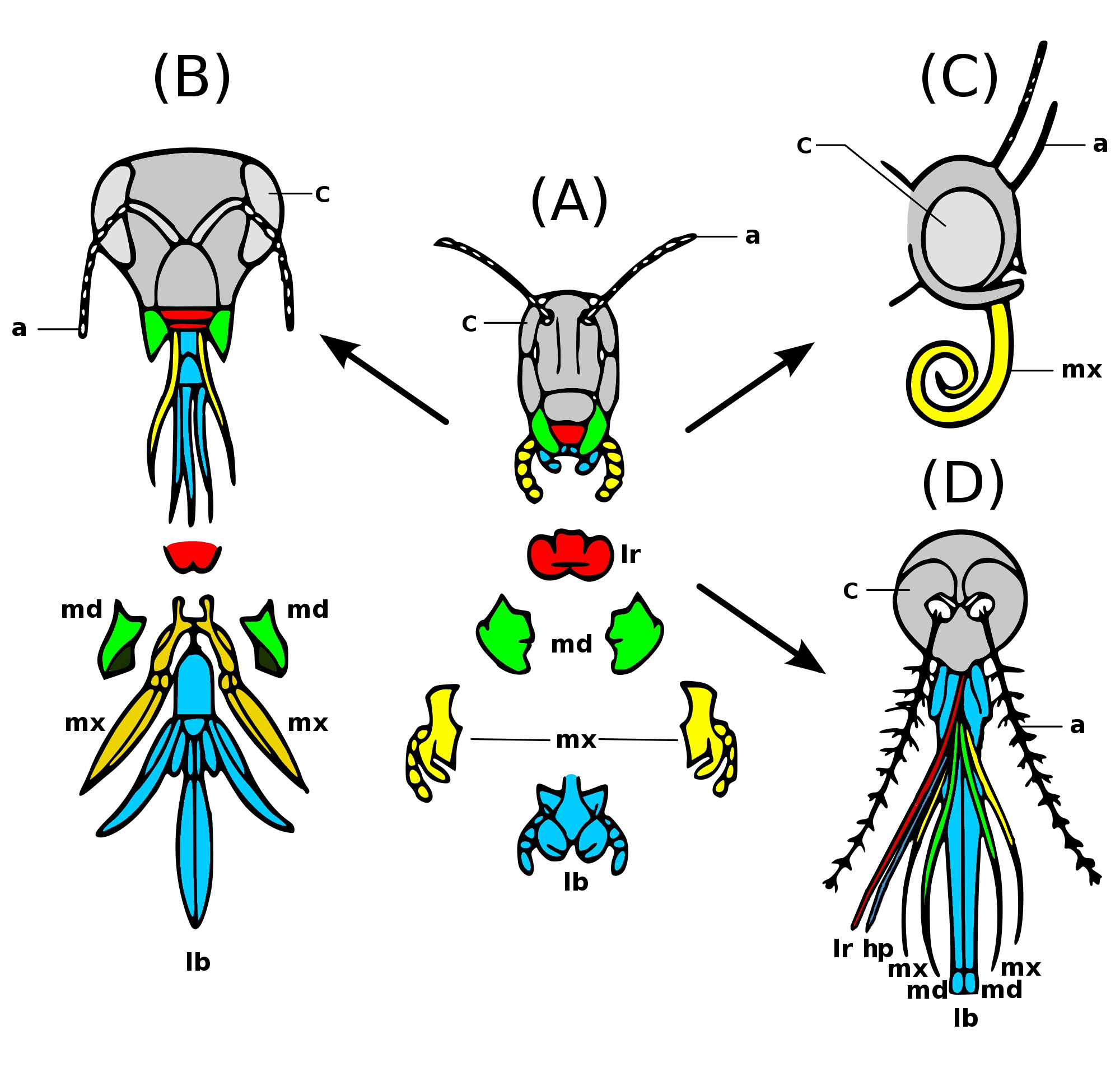

Insects have mouthparts that may vary greatly across insect species, as they are adapted to particular modes of feeding. The earliest insects had chewing mouthparts. Most specialisation of mouthparts are for piercing and sucking, and this mode of feeding has evolved a number of times independently. For example, mosquitoes (which are true flies) and aphids (which are true bugs) both pierce and suck, though female mosquitoes feed on animal blood whereas aphids feed on plant fluids.

Evolution

[edit]Insect mouthparts show a multitude of different functional mechanisms across the wide diversity of insect species. It is common for significant homology to be conserved, with matching structures forming from matching primordia, and having the same evolutionary origin. However, even if structures are almost physically and functionally identical, they may not be homologous; their analogous functions and appearance might be the product of convergent evolution.[citation needed]

Chewing insects

[edit]

1 Labrum

2 Mandibles;

3 Maxillae

4 Labium

5 Hypopharynx

Examples of chewing insects include dragonflies, grasshoppers and beetles. Some insects do not have chewing mouthparts as adults but chew solid food in their larval phase. The moths and butterflies are major examples of such adaptations.

Mandible

[edit]

Mandibles in insects are pairs of hardened structures that are used to grind, crush and chew food.[1] Mandibles have a broad molar region with ridged structures lined across to assist during chewing before it is swallowed.[2] When paired with the maxillae (upper jaw structures), it is referred to as one of the gnathal appendages.[3]

In carnivorous chewing insects, the mandibles commonly are particularly serrated and knife-like, and often with piercing points. In herbivorous chewing insects mandibles tend to be broader and flatter on their opposing faces, as for example in caterpillars.

In males of some species, such as of Lucanidae and some Cerambycidae, the mandibles are modified to such an extent that they do not serve any feeding function, but are instead used to defend mating sites from other males. In some ants and termites, the mandibles also serve a defensive function (particularly in soldier castes). In bull ants, the mandibles are elongate and toothed, used both as hunting and defensive appendages. In bees, that feed primarily by the use of a proboscis, the primary use of the mandibles is to manipulate and shape wax, and many paper wasps have mandibles adapted to scraping and ingesting wood fibres.

Maxilla

[edit]Situated beneath (caudal to) the mandibles, paired maxillae manipulate and, in chewing insects, partly masticate, food. Each maxilla consists of two parts, the proximal cardo (plural cardines), and distal stipes (plural stipites). At the apex of each stipes are two lobes, the inner lacinia and outer galea (plurals laciniae and galeae). At the outer margin, the typical galea is a cupped or scoop-like structure, located over the outer edge of the labium. In non-chewing insects, such as adult Lepidoptera, the maxillae may be drastically adapted to other functions.

Unlike the mandibles, but like the labium, the maxillae bear lateral palps on their stipites. These palps serve as organs of touch and taste in feeding and in the inspection of potential foods and/or prey.

In chewing insects, adductor and abductor muscles extend from inside the cranium to within the bases of the stipites and cardines much as happens with the mandibles in feeding, and also in using the maxillae as tools. To some extent the maxillae are more mobile than the mandibles, and the galeae, laciniae, and palps also can move up and down somewhat, in the sagittal plane, both in feeding and in working, for example in nest building by mud-dauber wasps.

Maxillae in most insects function partly like mandibles in feeding, but they are more mobile and less heavily sclerotised than mandibles, so they are more important in manipulating soft, liquid, or particulate food rather than cutting or crushing food such as material that requires the mandibles to cut or crush.

Like the mandibles, maxillae are innervated by the subesophageal ganglia.

Labium

[edit]The labium typically is a roughly quadrilateral structure, formed by paired, fused secondary maxillae.[4] It is the major component of the floor of the mouth. Typically, together with the maxillae, the labium assists manipulation of food during mastication.

The role of the labium in some insects, however, is adapted to special functions; perhaps the most dramatic example is in the jaws of the nymphs of the Odonata, the dragonflies and damselflies. In these insects, the labium folds neatly beneath the head and thorax, but the insect can flick it out to snatch prey and bear it back to the head, where the chewing mouthparts can demolish it and swallow the particles.[citation needed]

The labium is attached at the rear end of the structure called cibarium, and its broad basal portion is divided into regions called the submentum, which is the proximal part, the mentum in the middle, and the prementum, which is the distal section, and furthest anterior.

The prementum bears a structure called the ligula; this consists of an inner pair of lobes called glossae and a lateral pair called paraglossae. These structures are homologous to the lacinia and galea of maxillae. The labial palps borne on the sides of labium are the counterparts of maxillary palps. Like the maxillary palps, the labial palps aid sensory function in eating. In many species the musculature of the labium is much more complex than that of the other jaws, because in most, the ligula, palps and prementum all can be moved independently.

The labium is innervated by the sub-esophageal ganglia.[5][6][7]

In the honey bee, the labium is elongated to form a tube and tongue, and these insects are classified as having both chewing and lapping mouthparts. [8]

The wild silk moth (Bombyx mandarina) is an example of an insect that has small labial palpi and no maxillary palpi.[9]

Hypopharynx

[edit]The hypopharynx is a somewhat globular structure, located medially to the mandibles and the maxillae. In many species it is membranous and associated with salivary glands. It assists in swallowing the food. The hypopharynx divides the oral cavity into two parts: the cibarium or dorsal food pouch and ventral salivarium into which the salivary duct opens.

Siphoning insects

[edit]

This section deals only with insects that feed by sucking fluids, as a rule without piercing their food first, and without sponging or licking. Typical examples are adult moths and butterflies. As is usually the case with insects, there are variations: some moths, such as species of Serrodes and Achaea do pierce fruit to the extent that they are regarded as serious orchard pests.[10] Some moths do not feed after emerging from the pupa, and have greatly reduced, vestigial mouthparts or none at all. All but a few adult Lepidoptera lack mandibles (the superfamily known as the mandibulate moths have fully developed mandibles as adults), but also have the remaining mouthparts in the form of an elongated sucking tube, the proboscis.

Proboscis

[edit]The proboscis, as seen in adult Lepidoptera, is one of the defining characteristics of the morphology of the order; it is a long tube formed by the paired galeae of the maxillae. Unlike sucking organs in other orders of insects, the Lepidopteran proboscis can coil up so completely that it can fit under the head when not in use. During feeding, however, it extends to reach the nectar of flowers or other fluids. In certain specialist pollinators, the proboscis may be several times the body length of the moth.

Piercing and sucking insects

[edit]A number of insect orders (or more precisely families within them) have mouthparts that pierce food items to enable sucking of internal fluids. Some are herbivorous, like aphids and leafhoppers, while others are carnivorous, like assassin bugs and female mosquitoes. Thrips, insects of the order Thysanoptera, have unique mouthparts in that they only develop the left mandible, making the mouthparts asymmetrical. Some consider thrips to have piercing-sucking mouthparts, but others describe them as rasping-sucking.[11]

Stylets

[edit]

In female mosquitoes, all mouthparts are elongated. The labium encloses all other mouthparts, the stylets, like a sheath. The labrum forms the main feeding tube, through which blood is sucked. The sharp tips of the labrum and maxillae pierce the host's skin. During piercing, the labium remains outside the food item's skin, folding away from the stylets.[12] Saliva containing anticoagulants, is injected into the food item and blood sucked out, each through different tubes.

Proboscis

[edit]The defining feature of the order Hemiptera is the possession of mouthparts where the mandibles and maxillae are modified into a proboscis, sheathed within a modified labium, which is capable of piercing tissues and sucking out the liquids. For example, true bugs, such as shield bugs, feed on the fluids of plants. Predatory bugs such as assassin bugs have the same mouthparts, but they are used to pierce the cuticles of captured prey.

Sponging insects

[edit]

Labellum

[edit]The housefly is a typical sponging insect. The labellum's surface is covered by minute food channels, known as pseudotrachea, formed by the interlocking elongate hypopharynx and epipharynx, forming a proboscis used to channel liquid food to the oesophagus. The food channel draws liquid and liquified food to the oesophagus by capillary action. The housefly is able to eat solid food by secreting saliva and dabbing it over the food item. As the saliva dissolves the food, the solution is then drawn up into the mouth as a liquid.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ "Mouthparts – ENT 425 – General Entymology". NC State Agriculture and Life Sciences. Archived from the original on 2025-03-24. Retrieved 2025-07-10.

- ^ Krenn 2020, p. 20

- ^ Resh & Cardé 2009, p. 13

- ^ Richards, O. W.; Davies, R.G. (1977). Imms' General Textbook of Entomology: Volume 1: Structure, Physiology and Development. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 0-412-61390-5.[page needed]

- ^ Insect Mouthparts

- ^ Insect mouthparts - Amateur Entomologists' Society (AES)

- ^ "Structure and function of insect mouthparts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ^ "Hymenoptera: ants, bees and wasps", CSIRO, retrieved 8 April 2012

- ^ Heppner, John B; Richman, David B; Naranjo, Steven E; Habeck, Dale; Asaro, Christopher; Boevé, Jean-Luc; Baumgärtner, Johann; Schneider, David C; Lambdin, Paris; Cave, Ronald D; Ratcliffe, Brett C; Heppner, John B; Baldwin, Rebecca W; Scherer, Clay W; Frank, J. Howard; Dunford, James C; Somma, Louis A; Richman, David. B; Krafsur, E. S; Crooker, Allen; Heppner, John B; Capinera, John L; Menalled, Fabián D; Liebman, Matt; Capinera, John L; Teal, Peter E. A; Hoy, Marjorie A; Lloyd, James E; Sivinski, John; et al. (2008). "Silkworm Moths (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae)". Encyclopedia of Entomology. pp. 3375–6. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6359-6_4198. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- ^ Walter Reuther (1989). The Citrus Industry: Crop protection, postharvest technology, and early history of citrus research in California. UCANR Publications. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-931876-87-5.

- ^ Resh & Cardé 2009, p. 900

- ^ Zahran, Nagwan; Sawires, Sameh; Hamza, Ali (2022-10-25). "Piercing and sucking mouth parts sensilla of irradiated mosquito, Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) with gamma radiation". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 17833. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1217833Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-22348-0. PMC 9596698. PMID 36284127.

- ^ Mehlhorn, Heinz (2001). Encyclopedic Reference of Parasitology: Biology, Structure, Function. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 310. ISBN 978-3-540-66819-0.

Bibliography

[edit]- Krenn, Harald (2020). Insect mouthparts : form, function, development and performance. Cham: Springer Nature. ISBN 9783030296544. OCLC 1132426601.

- Resh, Vincent; Cardé, Ring (2009). Encyclopedia of insects (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 9780080920900. OCLC 500570904.