Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lal Bagh

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Lalbagh Botanical Garden or simply Lalbagh (lit. 'red garden'), is a botanical garden in Bengaluru, India. It was originally built by Hyder Ali in 1760, during the Sultanate of Mysore . The garden was later managed under numerous British superintendents before Indian Independence. It was responsible for the introduction and propagation of numerous ornamental plants as well as those of economic value. It also served a social function as a park and recreational space, with a central glass house dating from 1890 which was used for flower shows. In modern times, it hosts two flower shows coinciding with the week of Republic Day (26 January) and Independence Day (15 August). As an urban green space along with Cubbon Park, it is also home to numerous wild species of birds and other wildlife. The garden also has a lake adjoining a large rock on which a watchtower had been constructed during the reign of Kempegowda II.

History

[edit]

King Hyder Ali commissioned the building of this garden in 1760, but his son, King Tipu Sultan, completed it. A Bagh is Hindustani for garden while the reference of the prefix Lal is debated and could refer to the colour red due to its original floral composition but Lal also means "beloved". King Hyder Ali decided to create this garden on the lines of the Mughal Gardens that were gaining popularity during his time. King Hyder Ali laid out these famous botanical gardens and his son King Tipu Sultan added horticultural wealth to them by importing trees and plants from several countries. King Hyder Ali and King Tipu Sultan's Lalbagh gardens were managed by Mohammed Ali and his son Abdul Khader, and were based on design of the Mughal Gardens that once stood at Sira, at a distance of 120 km from Bengaluru. At that time, Sira was the headquarters of the strategically important southernmost Mughal "suba" (province) of the Deccan before the British Raj.[2]

The Lalbagh gardens were commissioned by the 18th century; over the years, it acquired India's first lawn-clock and the subcontinent's largest collection of rare plants.[3] After the British conquest of Kingdom of Mysore in 1799, the garden was under the charge of Major Gilbert Waugh, Company paymaster and in 1814 its control was transferred to the Government of Mysore with an appeal by Waugh to the Marquis of Hastings that it should be under the botanical garden at Fort William, Calcutta. This was accepted and the charge for supervision was given to Nathaniel Wallich on 24 April 1819. This continued until 1831 when charge moved to the Mysore Commissioner. An Agricultural and Horticultural Society had been formed with William Munro, an army officer and amateur botanist in charge of the Bengaluru chapter. The Society wrote to the Mysore Commissioner, Sir Mark Cubbon, requesting charge of the Lalbagh garden. Cubbon granted control and during this period it was used for horticultural training. The Bengaluru chapter of the Society was dissolved in 1842, leaving the gardens unmanaged.[1][4]

In 1855, Hugh Cleghorn, was appointed as a botanical advisor to the Commissioner of Mysore. Cleghorn and Jaffrey, superintendent of the Madras Agri-Horticultural Society looked at various sites for a horticultural garden and found that Lalbagh suited their purpose despite being located at a distance from the Cantonment, the British centre of the city. He suggested that a European Superintendent be appointed with control under the Chief Commissioner. Cleghorn was against the use of Lalbagh for commercial enterprise and instead suggested that it should aim to improve the use of indigenous plants, aid in introducing useful exotic species and help in the exchange of plant and seed materials with other gardens at Madras, Calcutta and Ooty. Under Cubbon's orders, Lalbagh was made into the Government Botanical Garden in August 1856 and a professional horticulturist was sought from Kew. William New was recommended and he arrived at Bengaluru on 10 April 1858. New's contract ended in 1863-64 and he was replaced by Allan Adamson Black who worked at the Kew Herbarium.[1][4]

Black, however, suffered from poor health and resigned in 1865. He died after visiting his brother in Rangoon aboard HMS Dalhousie, off the Coco Islands on 4 December 1865.[5] New was then re-appointed. In his 1861 catalogue of the plants of Lalbagh, there were numerous economic and ornamental plants including Cinchona, coffee, tea, macadamia nuts, hickory, pecan, rhododendrons, camellias, and bougainvilleas. New died in 1873 and was followed by John Cameron, also from Kew. Cameron had the additional support of the Maharaja of Mysore who was appointed in 1881 and introductions included Araucarias (A. cookii and A. bidwilli), cypresses (Cupressus sempervirens), topiaries made from Hamelia patens.[6]

In 1890-91, a central bandstand and the glasshouse (for flowershows) made with iron pillars cast by Walter Macfarlane and Company of Glasgow were added. Cameron also helped introduce commercial crops like cabbage, cauliflower, turnip, radish, rhubarb, celery, and kohlrabi. Trees introduced included the baobab from Africa, Brownea rosea from the Caribbean, and Catha edulis from Yemen.[6] Cameron retired in 1908 and was followed by Gustav Herman Krumbiegel.[4] A menagerie and an aviary had been established in the 1860s. A 15 ft high pigeon house or dovecote for 200 birds was built in 1893 south of the Glass House.[7] Following the plague the maintenance deteriorated and there was a proposal to close the menagerie and aviary in the 1900s. in 1914. Captain S.S.Flower reported that it included a court built between 1850 and 1860 having tigers and rhinoceros; an aviary; a monkey house with an orangutan; a paddock with blackbuck, chital, Sambar deer, barking deer, and a pair of emus; a bear house and a peacock enclosure.[8][9]

In 1874, Lalbagh had an area of 45 acres (180,000 m2). In 1889, 30 acres were added to the eastern side, followed by 13 acres in 1891 including the rock with Kempegowda tower and 94 acres more in 1894 on the eastern side just below the rock bringing it to a total of 188 acres (760,000 m2).[10] The foundation stone for the Glass House, modeled on London's Crystal Palace was laid on 30 November 1889 by Prince Albert Victor and was built during the time of John Cameron.[10][11] It was built with cast iron from the Saracen Foundry in Glasgow UK. This structure was extended in 1935, this time with steel from the Mysore Iron and Steel Company at Bhadravathi.[4]

The Horticultural Department decided to close Lalbagh Botanical Garden on Saturday 21 March 2020, in order to avoid public gatherings in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.[12] In the third week of May the government allowed parks to be open only from 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. to 7 p.m.[13]

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the cancellation of the Lalbagh flower show on Independence Day in 2020.[14] Due to the pandemic, mango and jackfruit melas were also not conducted at Lalbagh in 2020.[15]

Overview

[edit]Lalbagh is a 240 acres (0.97 km2) garden and is located in south Bengaluru. It holds two flower shows and has over 1,000 species of plants with many trees that are more than a hundred years old.[16][17][18]

The garden adjoins one of the towers erected by the founder of Bengaluru, Kempe Gowda. The park has some rare species of plants brought from Persia, Afghanistan and France. With an intricate watering system for irrigation, this garden is aesthetically designed, with lawns, flowerbeds, lotus pools and fountains. Most of the centuries-old trees are labelled for easy identification. The Lalbagh Rock, one of the most ancient rock formations on earth, dating back to 3,000 million years, is another attraction that attracts the crowds.[17]

Gates

[edit]Lalbagh has four gates numbered 1 to 4. Gates 1 and 2 are on the north side. Gate 3 is to the east and Gate 4 is to the west. The eastern gate is situated near Siddapura Circle (K.H Circle - K.H Double Road) and one can enter this gate and enjoy the sylvan atmosphere of the garden. The northwestern wall adjoins Krumbiegal Road named after G.H. Krumbiegal, the last pre-Independence Superintendent.

The western gate has a wide road with Jayanagar, Bengaluru close by. The southern gate is often referred to as a small gate and opens near Ashoka pillar. The northern gate is a fairly wide and big road leading to the Glass House and serves as the primary entrance.[3]

Tourism and eco-development

[edit]Flower shows are conducted every year during the week of Republic day and Independence day, to educate people about the variety of flora and develop public interest in plant conservation and cultivation.[19] In August 2022, on the occasion of 75th Independence Day, flower show was conducted in the honour of Rajkumar and Puneeth Rajkumar depicting their life journey. It was attended by 8.34 lakh people.[20]

A bonsai garden has been added in 2002. Apart from this, there is a Topiary Garden, Rose Garden and Lotus Garden inside Lalbagh.[citation needed]

An artificial waterfall has been commissioned in 2017 at the far eastern edge of the lake.[21]

Lalbagh is a good place for bird watching both in the lake and on the ground.[citation needed]

Lalbagh also has a "Garden centre" where citizens can buy ornamental plants. This is managed by Nursery Men's Cooperative society.[22]

A geological monument for the peninsular gneiss formation is also a tourist attraction at the gardens. This monument has been designated by the Geological Survey of India on the Lalbagh hill which is made up of 3,000 million-year-old peninsular gneissic rocks. One of the four cardinal towers erected by Kempegowda II, also a major tourist attraction, is seen above this hillock. This tower gives a view of Bengaluru from the top.[23][24]

Lalbagh management and public protests

[edit]The Lalbagh botanical gardens is managed by the Department of Horticulture and is no longer maintained as a botanical garden and is not a member of the Botanic Gardens Conservation International.[25] With an increasing pressure to serve as a park and social space, much of the garden has been converted into walking paths and lawns. Morning walkers throng Lalbagh every morning. Many tree have been trimmed or cut down to make way for public amenities or due to perceptions that falling branches may threaten visitors.[26] A part of the garden was taken over and many trees cut down amid protests for construction of the Lalbagh Metro Station as part of the Bengaluru Metro Rail Corporation Ltd. Entry fees of INR 25 with a camera fee of INR 60 have also been a point of contention.[27] There have been repeated proposals to build various recreational amenities such as rock gardens, fountains and boating facilities. Some of these proposals of the management have been halted in the past due protests from enlightened public who have pointed out the impacts these have on the environment.[28]

Connectivity

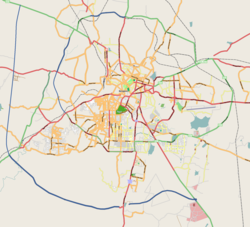

[edit]Lalbagh metro station connects with the Greenline of Namma Metro.[29]

Lalbagh is also connected by Bengaluru Metropolitan Transport Corporation buses from Kempegowda Bus Station/Shivaji Nagar. All buses towards Jayanagar/Banashankari areas pass through one of the four gates of Lalbagh.[citation needed]

Preservation Act, 1979

[edit]The Preservation Act, 1979 passed by the Government of Karnataka to preserve the uniqueness of the park is under the provision of Karnataka Government Park (Preservation) Act, 1975, which states:

Accordingly, it is directed that neither any land should be granted to nor any further constructions be permitted whether temporary or permanent by any organization or individuals in the Cubbon Park and Lalbagh areas except the constructions taken up by the Horticulture Department in furtherance of the objectives of the department.[30]

Gallery

[edit]- Lalbagh Gallery

-

Lalbagh or Lalbagh Botanical Gardens is a well known botanical garden in southern Bengaluru, India.

-

Kempegowda tower

-

Side view of Glass House

-

Interior view of the Glass house

-

Largest known Bombax malabaricum,[6]: 23 'red silk-cotton' or 'kapok' specimen, (sometimes listed as Ceiba pentandra) located in Lalbagh

-

Evening View of the Lake

-

A Japanese decorative monument found in Lalbagh

-

Lalbagh Lake pathway

-

A statue of Sri Chamarajendra Wodeyar, ex-ruler of Mysore at Lalbagh. He also sponsored the famous journey of Swami Vivekananda to Chicago in 1893.

-

A view of the lake at Lalbagh

-

Lawn inside Lalbagh

-

Lotus Pond

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Vinoda, K (October 1989). The Lalbagh - A History. p. 5. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Benjamin Rice, Lewis (1897). Mysore: A Gazetteer Compiled for the Government, Volume I, Mysore In General, 1897a. Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company. p. 834.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b "History of Lalbagh Botanical Garden". Directorate of Horticulture, Government of Karnataka. 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d Bowe, Patrick (2012). "Lal Bagh - The botanical garden of Bangalore and its Kew-trained gardeners". Garden History. 40 (2): 228–238. ISSN 0307-1243. JSTOR 41719905.

- ^ "Death". Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette. 23 January 1866. p. 3.

- ^ a b c Cameron, John (1891). Catalogue of plants in the Botanical Garden, Bangalore and its vicinity (2 ed.). Bangalore: Government Press.

- ^ Thiruvady V R (2020). Lalbagh: Sultan's Garden to Public Park. Bangalore: Bangalore Environment Trust. ISBN 9798189650949.

- ^ Flower, S.S. (1914). Report on a Zoological mission to India. Cairo: Government Press. pp. 40–41.

- ^ Vinoda, K. (1989) The Lalbagh - A history 1760-1932. Department of History, Bangalore University.

- ^ a b "A jewel in Lalbagh's crown". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ Suresh Singh, Kumar (2003). People of India: Karnataka Vol. xxvi. Affiliated East-West Press (Pvt.) Ltd. ISBN 978-8-1859-3898-1.

- ^ "COVID-19: Cubbon Park and Lalbagh Garden in Bengaluru closed". The News Minute. 22 March 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Walkers throng Bengaluru's Cubbon Park, Lalbagh, officials have tough time". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Y Maheswara Reddy (6 July 2020). "Covid-19 forces flower show at Lalbagh Botanical Garden to be called off". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Special Correspondent (5 July 2020). "Independence Day flower show at Lalbagh cancelled". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Lalbagh Botanical Garden, Bangalore (PDF), Department of Horticulture, Bangalore, archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2023

- ^ a b "Lalbagh Botanical Garden, Bangalore". Department of Horticulture, Bangalore. Archived from the original on 5 February 2005. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ Bowe, Patrick (2002). "Charles Maries: Garden Superintendent to Two Indian Maharajas". Garden History. 30 (1: Spring): 84−94. doi:10.2307/1587328.

- ^ "Lal Bagh Flower Show 2008 Ticket Booking". Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ "Record 8.34 lakh people flock to flower show, revenue touches Rs 3.33 crore". The New Indian Express. 16 August 2022. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Double joy: Visitors to Lalbagh can now enjoy two waterfalls". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "The Nurserymen Co-Operative Society Ltd". ncslalbagh.com. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Peninsular Gneiss". Geological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ "National Geological Monuments, pages 96, Peninsular Gneiss, page29-32". Special Publication Series. Geological Survey of India,27, Jawaharlal Nehru Road, Kolkata-700016. 2001. ISSN 0254-0436. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ "Lalbagh Botanical Garden". BGCI. Botanic Gardens Conservation International.

- ^ "No more tree felling at Lalbagh: Minister". Deccan Herald. 7 August 2010.

- ^ Kidiyoor, Suchith (7 October 2018). "Entry, parking fees at Lalbagh set to go up". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019.

- ^ Mukherjee, Saswati (21 July 2014). "Making Lalbagh see green". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 1 November 2022.

- ^ "Nagasandra-Puttenahalli Metro line: Nagasandra-Puttenahalli Metro line to open by May-end, says KJ George". The Times of India. TNN. 3 May 2017. Bengaluru News. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ "GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA". 13 November 2008. Archived from the original on 13 November 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

![Largest known Bombax malabaricum,[6]: 23 'red silk-cotton' or 'kapok' specimen, (sometimes listed as Ceiba pentandra) located in Lalbagh](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/Bombax_LalBagh.JPG/250px-Bombax_LalBagh.JPG)