Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lighterman

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2021) |

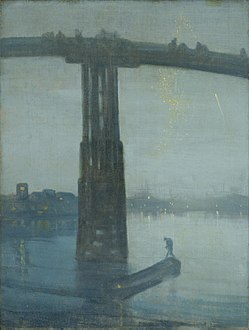

A lighterman is a worker who operates a lighter, a type of flat-bottomed barge, which may be powered or unpowered. In the latter case, it is usually moved by a powered tug. The term is particularly associated with the highly skilled men who operated the unpowered lighters moved by oar and water currents in the Port of London.

Lightermen in the Port of London

[edit]History

[edit]Lightermen were one of the most characteristic groups of workers in London's docks during the heyday of the Port of London, but their trade was eventually rendered largely obsolete by changes in shipping technology. They were closely associated with the watermen, who carried passengers, and in 1700 joined the Company of Watermen to form the Company of Watermen and Lightermen. This is not, strictly speaking, a livery company but a "City Company Without Grant of Livery", formed in 1700 by an act of Parliament, the Thames Watermen Act 1698 (11 Will. 3. c. 21). The guild continues to license watermen and lightermen working on the River Thames. Watermans' Hall is located at 16 St Mary At Hill, in Billingsgate. It dates to 1780 and is the only surviving Georgian guild hall.

The construction of the docks was bitterly opposed by the lightermen and other vested interests, but went ahead anyway. However, they did win a major concession: that became known as the "free-water clause", first introduced into the West India Dock Act 1799 (39 Geo. 3. c. lxix) and subsequently written into the Acts governing all of the other docks. This stated that there was to be no charge for "lighters or craft entering into the docks ... to convey, deliver, discharge or receive ballast or goods to or from on board any ship ... or vessel." This was intended to give lighters and barges the same freedom in docks that they enjoyed on the open river. In practice, however, this proved highly damaging to the dock owners. It allowed ships to be loaded and unloaded overside, using barges and lighters to transfer their goods to and from riverside wharves rather than dock quays, thus bypassing quay dues and dock warehouses. This significantly reduced the docks' income and harmed their finances, while boosting the profits of their riverside competitors. Not surprisingly, the dock owners lobbied vigorously—but unsuccessfully—for the abolition of this damaging privilege.

Operation

[edit]

The lightermen were a vital component of the Port of London before the enclosed docks were built during the 19th and 20th centuries. Ships anchored in the middle of the Thames or near bridge arches transferred their goods aboard or in respect of a few exports from lighters. Lightermen rode the river's currents—westward, when the tide was coming in, eastward on the ebb tide—to transfer the goods to quay-sides. They also transferred goods up and down the river from quays to riverside factories and vice versa. This was an extremely skilled job, requiring an intimate knowledge of the river's currents and tides. It also demanded a lot of muscle power, as the lighters were unpowered; they relied on the current for motive force and on long oars, or "paddles",[1] for steering.

The lightermen's trade was eventually swept away by the docks mentioned, as well as economic and technological changes, particularly the introduction of containers, which led to the closure of London's major central docks in the 1960s.

Few written accounts of the process of becoming an apprentice now exist, though the best-known is Men of the Tideway by Dick Fagan and Eric Burgess. (Fagan worked as a lighterman for more than forty years). In the book, Fagan mentions the exploitative nature of lighterage and expresses his disdain for what he called a "free-for-all capitalist system".[2]

The term lighterman is still used for the workers who operate motorised lighters to access a vessel which is too large or due to conditions unable to moor at a dock and the phrase to alight goods is used in the goods trade widely compared to the phrase 'alighting of passengers' which has become archaic across most of the English-speaking world except in formal contexts and on some railways, having been generally replaced with the terms 'exit', 'leave', or 'depart'.

Lightermen in Hull

[edit]The Humber Estuary causes similar problems to the Thames plus vast shifting sandbanks. For centuries the Port of Hull took much of its traffic in transfer of cargoes between vessels as Hull was cut off from safe land routes for much of the year. Lightermen were experts in these transfers and also in guiding vessels to safe moorings away from the sandbanks. By the 19th century, enclosed docks were being built but only with the arrival of steam barges late in the century did the Lightermen's expertise become redundant. A sub-category consisted of ballast lightermen, specialising in transferring rubble, bricks, and cobbles to and from the lower holds of vessels to keep them upright even in severe storms.

Lightermen in Singapore

[edit]

As with their English counterparts, lightermen in Singapore were men who worked on a lighter or on a barge.[3] Their primary role was to transport cargo between ships in the harbour and warehouses along the Singapore River.[4] They were active in Singapore in the 19th and 20th century, playing a key role in the city’s port functions. They were mostly migrant labourers from India or China and worked in teams ranging from two to four aboard tongkangs and twakows.[4] Lighterman had to be skilled in managing cargo boats as they dealt with many valuable goods that could easily be damaged or misplaced. Before the introduction of motorised boats, they were also required to have the skills to manage their boats with just oar and sail.[5]

Lighterage in Singapore

[edit]Singapore developed rapidly in the 19th to 20th century, owing much of its accomplishments to its development as an important trading port.[6] The Singapore River was the initial site of trade and formation of lighterage services was indispensable in Singapore’s initial success as the river was too narrow and shallow for ships to enter.[7] Large merchant vessels had to cast anchor at the harbour before transferring their goods into the lighters.[8] From there, lightermen would then transport the cargo between warehouses by the river. These lightermen, by enabling Singapore’s smooth functioning as a port, were essential figures that, while lesser known, have contributed greatly to the city’s success. As such, the lighterage industry was one of the first major service industries to develop in Singapore.

History of lightermen in Singapore

[edit]19th century: Indian lightermen

[edit]Between the period of 1819 to 1900, South Indian lightermen were the dominant group leading Singapore’s lighterage industry.[8] Consisting mainly of Chulias, Muslims who hailed from the Coromandel Coast at the southeastern coastal region of the Indian subcontinent in the 1800s, many of the earlier lightermen were also recruited through the East India Company’s port at Madras.[9][10]

However, in the later half of the 1800s, the position of these Indian lightermen began to weaken. Numerous reasons for this decline included the transference of the Straits Settlements to the Colonial Office, which resulted in the loss of the close connection and link with the administration that operated in India.[9] The movement of European merchants’ operations from the Singapore River to New Harbour also affected the livelihoods of Indian lightermen as lighters were not needed to move goods there.[8]

The tongkang was the first of the lighter boats used by the Indian lightermen along the Singapore River. They were generally large, ranging in size from 20 to 120 tonnes, making it difficult to control.[4] However, this also meant that the lighters could offer greater protection to the cargo they carried.

20th century: Chinese lightermen

[edit]Between the early twentieth century up to 1983 when the Singapore government proceeded to remove the lighters from the river, the lighterage industry came to be dominated by Chinese boatmen.[5]

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, many Chinese migrated to Singapore to seek wealth and better lives.[11] This was in response to a cumulation of push and pull factors such as political and social turmoil in China, as well as the rising status of Singapore as an important trading entrepot. With the large influx of Chinese migrants in the late 19th centuries, Chinese lighters and lightermen started to inevitably replace their Indian counterparts.

Two main Chinese dialect groups dominated the lighterage industry, namely the Hokkiens from the Fujian province and the Teochews from the Guangdong area.[5] In the years during the initial phase of Chinese domination leading to World War II, the Teochews essentially controlled the lighterage industry along the Singapore River. Nearly three quarters of the twakow in the river then were run and staffed by the Teochews. The other one quarter of the twakow were owned and operated by the Hokkiens. However, the twakow owned by the Hokkien mostly transported cargo from along the waterfront within the Telok Ayer Basin and less from the river itself. This business strategy changed after the war as the Hokkiens became the predominant conveyors of trading commodities in the river.[5]

The twakow was the lighter vessel used by Chinese lightermen in the late 19th to early 20th century. By 1900, it had replaced the tongkangs used by Indian lightermen as the preferred lighter for transporting goods between ships as they were more manoevurable.[8] The vessel stemmed from Chinese influence and had a wide hull and nearly flat bottom, features that made it well-suited for carrying heavy cargo in shallow waters. Traditional twakows, which used punt poles and sails, were used up to the 1950s, despite the emergence of motorized versions in the 1930s.[12]

Late 20th to 21st centuries: Changing urban landscape and economy

[edit]As Singapore became one of the busiest ports in the 20th century, technological advancements such as containerism and the government’s decision to rely less on river-borne trade caused the previously crucial role of the Singapore River as a commercial hub to decline.[13] As a result, jobs centered on the Singapore River also started to lose their importance, with the lighterage industry being no exception. The clean up of the Singapore River was also linked to the introduction of the Housing and Development Board (HDB) which was in charge of rehousing the river communities.[14]

Another key factor leading to the decline of lightermen was the Singapore government’s effort towards urban-environmental renewal through the Clean Rivers Campaign in the 1980s.[15] The campaign saw the removal of all lighters from the Singapore River in the cleaning process and was the catalyst in their relocation and disappearance.[14] By September 1983, lighterage activities which included approximately 800 lighters were relocated to facilities of the Port of Singapore Authority at Pasir Panjang.[13]

About

[edit]Occupation

[edit]In Singapore, lightermen existed along the same spectrum of life as coolies as labourers coming from India and China. Yet, they had different roles in the early days of Singapore as they contributed to the city’s development. Coolies were often unskilled labourers, employed as manual labour in nearly every sector.[16] They were employed in various areas such as construction and plantation work. On the other hand, lightermen were distinctly situated along the Singapore River, transporting goods from ships to land. Lighterage work also required great skill and strength to load and maneuver lighters. While the main transfer of goods to lighters were carried out by coolies and stevedores, lighters would personally load their craft with the goods, as a poorly loaded lighter could cause the boat to be unstable on water.[4]

Working conditions

[edit]The lightermen faced harsh working conditions due to the physically demanding and dangerous nature of the work.

The work of lightermen was high risk and immensely back-breaking. Demanding tremendous physical strength, some of the heaviest goods lightermen were tasked with included cases of dried fish that often exceeded 200 kilograms.[4] These crates were particularly tricky to maneuver as they were huge, bulky and haphazardly constructed. Before cranes were introduced, three coolies were even needed to hoist a single case which would be passed on to a waiting lighter.[4]

The challenges of handling bulky cargoes were further exacerbated by the conditions inside the vessel. Some of the bigger lighters had wide and deep undercarriages which would become unbearably hot and humid during certain months. Putrid and poisonous smells, coupled with the swaying and lurching unpredictably due to waves made the work as challenging as it was hazardous. It was difficult in itself to maintain one’s balance while avoiding being hit by goods that were lowered along the side of the vessel.[4]

The work also had erratic hours and lightermen would work when called for. Oftentimes, they were even known to work for more than 24 hours continuously, with minimal rest.[4]

Yet, in light of the skill and effort involved, lightermen were often held in higher regard and paid more than their peers in other manual labouring occupations.

Relationships

[edit]Towkays

[edit]Lightermen worked under Chinese businessmen called towkays.[17] The lightermen and their towkays generally shared a strong reciprocal relationship that exceeded the standard for typical employers and employees as it was one that was built on mutual trust and reciprocity.

Towkays had the responsibility of caring for the welfare of their lightermen, being a reliable figure that they could turn to regardless of difficulties. This could be through advance payments in financial difficulties, or providing less strenuous work upon retiring from lighterage work.[4] These welfare measures were especially important to lightermen as they were often unmarried migrants with no local connections.

Coworkers

[edit]Lightermen worked in teams and often shared close, familial relationships with their coworkers. Many lightermen were employed by and with those that shared a common dialect, surname background, or other kinship lines.[4] This hiring practice was seen to be beneficial in ensuring a cohesive and efficient workforce. As a result, there was a close bond within the lightermen community as they often worked with those whom they shared a social bond with, and treated each other like family members. These positive relationships provided the lightermen with job security and a sense of belonging, and they changed jobs minimally.

Industrial organisation

[edit]Early labour disputes in the lighterage industry and on the river were uncommon and usually unrelated to work conditions. The earliest record of lightermen striking took place in 1842 and was connected to a large-scale protest by the Indian community against the government who did not permit a religious procession to take place along the streets.[4]

Lightermen’s main concerns in forming a union were to primarily ensure that they received fair payment and compensation for long hours and injuries incurred on the job.[18] Over the years, they formed several unions which achieved varying levels of success. These included the Lightermen's Union, the Transport Vessel Workers Association, and Singapore Lighter Workers’ Union.

Lightermen's Union

[edit]Formed in the late 1930s with 3000 members, the Lightermen's Union’s goal was to address and correct lightermen's grievances over their working conditions.[18] Despite the positive and harmonious relationship between lightermen and their towkays, the 1930s was a period of tension and volatility due to the pre-war environment. Labourers from all occupations gained increasing political awareness, especially of their political strength when banded together, and started forming unions. This also included the lightermen.

Transport Vessel Workers Association (TVWA)

[edit]The Lightermen's Union was subsequently reorganised their administration post-war and registered as the Transport Vessel Workers Association (TVWA). Yet, despite being formed for all lightermen, the union started to focus only on their representation of Chinese lightermen.[4] Due to the increasingly militant nature, biased attitudes and persisting rivalries of the union, many Indian lightermen left as a result and formed their own union.[14] This was short lived, however, as a number of Indian lightermen eventually did rejoin the union upon the failure of their own.

Through arbitration and negotiation, the union was relatively successful in achieving their goals. Members were able to receive the appropriate amount of pay and work with better conditions. More than that, the TVWA provided the lightermen with a sense of solidarity and allowed them a strong voice. This unity was so strong that it surpassed previous clan rivalries and even reduced the frequency of clashes between the Hokkien and Teochew lightermen.[4]

Singapore Lighter Workers' Union

[edit]The Singapore Lighter Workers' Union was formed by Indian lightermen working in the Telok Ayer Basin as a response to the growing Chinese-centric ideals of the Transport Vessel Workers Association.[4][19] It was generally unsuccessful, however, as it was unable to meet the demands of its members and was filled with controversy. The leaders of the union prioritised their own interests over that of their members and rumors of the misuse of union funds caused internal distrust and dissatisfaction.[4] The union soon collapsed, and further attempts at forming an Indian lightermen union were faced with failure.

References

[edit]- ^ Men of the Tideway by Dick Fagan and Eric Burgess, 1966 (See first sentence of p.22)

- ^ Fagan and Burgess, 1966 p.23

- ^ Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Lighterman. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Dobbs, S. (2016). Lighterage Work Conditions and Organisation. In The Singapore River: A Social History, 1819-2002 (pp. 53-76). NUS Press.

- ^ a b c d Dobbs, S. (2016). Lightermen: Migration and Destiny. In The Singapore River: A Social History, 1819-2002 (pp. 22-34). NUS Press.

- ^ Chua, B. H. (1997). From City to Nation: Planning Singapore. In Political Legitimacy and Housing (1st ed., pp. 27–50). Routledge.

- ^ Dobbs, S. (1994). “Tongkang, Twakow,” and Lightermen: A People’s History of the Singapore River. Sojourn (Singapore), 9(2), 269–276.

- ^ a b c d National Heritage Board. (2016, October). Singapore River Walk.

- ^ a b Gibson-Hill, C. A. (1952). Tongkang and Lighter Matters. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 25(1 (158)), 84–110.

- ^ Rajesh Rai. (2016). Indians in the Modelling of the Global Metropolis. In Pillai, G., & Kesavapany, K. (Eds.), 50 years of Indian community in Singapore (pp. 7-18). World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

- ^ Chen, D. (1939). Emigrant Communities in South China: A Study of Overseas Migration and Its Influence on Standards of Living and Social Change. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Roots. (n.d.). View of the Singapore River.

- ^ a b Joshi, Y. K., Tortajada, C., & Biswas, A. K. (2012). Cleaning of the Singapore River and Kallang Basin in Singapore: Human and Environmental Dimensions. Ambio, 41(7), 777–781.

- ^ a b c Loh, K. S. (2007). Black Areas: Urban Kampongs and Power Relations in Post-war Singapore Historiography. Sojourn (Singapore), 22(1), 1–29.

- ^ Dobbs, S. (2002). Urban Redevelopment and the Forced Eviction of Lighters from the Singapore River. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 23(3), 288–310.

- ^ Lim, T. S. (2015, October 1). Triads, Coolies and Pimps: Chinatown in Former Times. BiblioAsia.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. (n.d.). Towkay. In Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ a b The Straits Budget. (1939, December 14). Lightermen Ask For Increase In Wages. The Straits Budget.

- ^ The Straits Times. (1951, March 17). Indian Lightermen Seek Wage Rise. The Straits Times.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- Watermen's Hall Official Site

- Men of the Tideway by Fagan and Burgess (Chapters 1 & 2 available only)

- Waterman's Hall

- Company of Watermen and Lightermen

- http://www.portcities.org.uk/london/server/show/conMediaFile.1397/A-London-lighterman-c-1910.html

- Thames Lighterman photos NB: Website no longer available

- Lighterman apprentice certificates and licences

- Website dedicated to history of Lightermen

Bibliography

[edit]- Stephen Dobbs, The Singapore River, Part 1 - 3 Lightermen: Migration and destiny. This book devotes a chapter to Indian lightermen in the Singapore River.