Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Port of London

View on Wikipedia

The Port of London is that part of the River Thames in England lying between Teddington Lock and the defined boundary (since 1968, a line drawn from Foulness Point in Essex via Gunfleet Old Lighthouse to Warden Point in Kent)[1] with the North Sea and including any associated docks.[2] Once the largest port in the world, it was the United Kingdom's largest port as of 2020.[3] Usage is largely governed by the Port of London Authority ("PLA"), a public trust established in 1908; while mainly responsible for coordination and enforcement[4] of activities, it also has some minor operations of its own.[5]

Key Information

The port can handle cruise liners, roll-on roll-off ferries and cargo of all types at the larger facilities in its eastern extent. As with many similar historic European ports, such as Antwerp and Rotterdam, many activities have steadily moved downstream towards the open sea as ships have grown larger and the land upriver taken over for other uses.

History

[edit]

The Port of London has been central to the economy of London since the founding of the city in the 1st century and was a major contributor to the growth and success of the city. In the 18th and 19th centuries, it was the busiest port in the world, with wharves extending continuously along the Thames for 11 miles (18 km), and over 1,500 cranes handling 60,000 ships per year. It was a prime target for Nazi German bomber aircraft during World War II (the Blitz).

The Roman port in London

[edit]The first evidence of a reasonable sized trading in London can be seen during Roman control of Britain, at which time the Romans built the original harbour. The construction involved expanding the waterfront using wooden frames filled with dirt. Once these were in place, the wharf was built in four stages moving downstream from London Bridge.[6] The port began to rapidly grow and prosper during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, and saw its final demise in the early 5th century with the decline in trade activity due to the Roman departure from Britain. The changes made to the banks along the port made by the Romans are so substantial and long-lasting that it was hard to tell where the natural waterfront really began.[7][8] However, the harbour within the Roman town was already in decline at the end of the 2nd century AD. It seems likely that a proper port developed at about this time at Shadwell, about 1 mile (1.6 km) east of the Roman town [9]

London became a very important trading port for the Romans at its height in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. The harbour town grew and expanded quickly. The lavish nature of goods traded in London shaped the extravagant lifestyle of its citizens and the city flourished under Roman colonization.[10] The Roman expansion of port facilities and organisation of the London harbour have remained as the base of the London harbour.

Pool of London

[edit]

Until the beginning of the 19th century, shipping was handled entirely within the Pool of London on the stretch of the River Thames along Billingsgate on the south side of the City of London. All imported cargoes had to be delivered for inspection and assessment by Customs Officers, giving the area the name of "Legal Quays".[11] The Pool saw a phenomenal increase in both overseas and coastal trade in the second half of the 18th century. Two-thirds of coastal vessels using the Pool were colliers meeting an increase in the demand for coal as the population of London rose. Coastal trade virtually doubled between 1750 and 1796 reaching 11,964 vessels in 1795. In overseas trade, in 1751 the pool handled 1,682 ships and 234,639 tons of goods. By 1794, this had risen to 3,663 ships and 620,845 tons.[12] By this time, the river was lined with nearly continuous walls of wharves running for miles along both banks, and hundreds of ships moored in the river or alongside the quays. In the late 18th century, an ambitious scheme was proposed by Willey Reveley to straighten the Thames between Wapping and Woolwich Reach by cutting a new channel across the Rotherhithe, Isle of Dogs, and Greenwich peninsulas. The three great horseshoe bends would be cut off with locks, as huge wet docks.[13] This was not realised, though a much smaller channel, the City Canal, was subsequently cut across the Isle of Dogs.

Enclosed dock systems

[edit]

The enclosed docks had their origin in the lack of capacity in the Pool of London which particularly affected the West India trade. In 1799, the West India Dock Act allowed a new off-river dock to be built for produce from the West Indies,[11] and the rest of Docklands followed as landowners built enclosed docks with better security and facilities than the Pool's wharves.

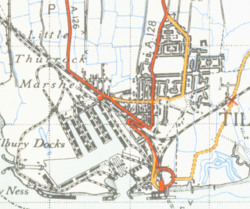

Throughout the 19th century, a series of enclosed dock systems was built, surrounded by high walls to protect cargoes from river piracy. These included West India Docks (1802), East India Docks (1803, originating from the Brunswick Dock of 1790), London Docks (1805), Surrey Commercial Docks (1807, originating from the Howland Great Wet Dock of 1696), St Katharine Docks (1828), Royal Victoria Dock (1855), Millwall Dock (1868), Royal Albert Dock (1880), and Tilbury docks (1886).

The enclosed docks were built by several rival private companies, notably the East & West India Docks Company (owners of the East India, West India, and Tilbury docks), Surrey Commercial Docks Company and London & St Katharine Docks Company (owners of the London, St Katharine and Royal docks). By the beginning of the 20th century, competition and strikes led to pressure for amalgamation. A Royal Commission led to the setting up of the Port of London Authority (PLA) in 1908. In 1909, the PLA took control of the enclosed docks from Tower Bridge to Tilbury, with a few minor exceptions such as Poplar Dock which remained as a railway company facility. It also took over control of the river between Teddington Lock and Yantlet Creek from the City corporation which had been responsible since the 13th century. The PLA head Office at Trinity Square Gardens was built by John Mowlem & Co and completed in 1919.[14]

The PLA dredged a deep water channel, added the King George V Dock (1920) to the Royal group, and made continuous improvements to the other enclosed dock systems throughout the first two-thirds of the 20th century. This culminated in expansion of Tilbury in the late 1960s to become a major container port (the UK's largest in the early 1970s), together with a huge riverside grain terminal and mechanised facilities for timber handling. Under the PLA, London's annual trade had grown to 60 million tons (38% of UK trade) by 1939, but was mainly transferred to the Clyde and Liverpool during World War 2. After the war, London recovered, again reaching 60 million tons in the 1960s.

| Year | Name | Company | Area (water area unless stated) |

Location name | Side of river |

Approx. river distance below London Bridge |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1802 | West India Docks | E&WIDC | North (Import) Dock: 30 acres (12 ha); Middle (Export) Dock: 24 acres (9.7 ha) |

Isle of Dogs | north | 3 mi (4.8 km) | |

| 1803 | East India Docks | E&WIDC | 18 acres (7.3 ha) | Blackwall | north | 7 mi (11 km) | Originating from the Brunswick Dock of 1790 |

| 1805 | London Docks | L&StKDC | Western Dock: 20 acres (8.1 ha); Eastern Dock: 7 acres (2.8 ha); 30 acres (12 ha) (land) |

Wapping | north | 1.5 mi (2.4 km) | |

| 1807 | Surrey Commercial Docks | SCDC | 17th-century original: 10 acres (4.0 ha); eventually reached: 460 acres (190 ha) |

Rotherhithe | south | 4 mi (6.4 km) | Originating from the Howland Great Wet Dock of 1696 |

| 1828 | St Katharine Docks | L&StKDC | 23 acres (9.3 ha) (land) | Tower Hamlets | north | 1 mi (1.6 km) | |

| 1855 | Royal Victoria Dock | L&StKDC | ? | Plaistow Marshes today Silvertown |

north | 8 mi (13 km) | |

| 1860s | South West India Dock | E&WIDC | ? | Isle of Dogs | north | 3.5 mi (5.6 km) | |

| 1868 | Millwall Dock | Millwall Dock Company | 36 acres (15 ha); 200 acres (81 ha) (land) |

Millwall | north | 4 mi (6.4 km) | |

| 1880 | Royal Albert Dock | L&StKDC | ? | Gallions Reach | north | 11.5 mi (18.5 km) | |

| 1886 | Tilbury Docks | E&WIDC | ? | Tilbury | north | 25 mi (40 km) | |

| 1912 | King George V Dock | PLA | 64 acres (26 ha) | North Woolwich | north | 11 mi (18 km) |

| Company name abbreviation |

Company name |

|---|---|

| E&WIDC | East & West India Docks Company |

| L&StKDC | London & St Katharine Docks Company |

| SCDC | Surrey Commercial Docks Company |

| PLA | Port of London Authority |

Dockhands

[edit]

By 1900, the wharves and docks were receiving about 7.5 million tons of cargo each; an inevitable result of the extending reach of the British Empire.[15] Of course, because of its size and grandeur, the Port was a place of work for many labourers in late 19th and early 20th century London. While most of the dockers were casual labourers, there were skilled stevedores who loaded ships, and lightermen who unloaded cargo from moored boats via barges. While these specific dockhands found regular work, the average dockhand lived day to day, hoping he would be hired whenever a ship came in. Many times these workers would actually bribe simply for a day's work; and a day's work could be 24 hours of continuous labouring. In addition, the work itself was incredibly dangerous. A docker would suffer a fatal injury from falling cargo almost every week during 1900, and non-fatal injuries were even more frequent.[16]

The London dockers handled exotic imports such as precious stones, African ivory, Indian spices, and Jamaican rum that they could never dream of purchasing themselves, and so robberies were very common on the London docks. Dockers would leave work with goods hidden under their clothes, and robbers would break into warehouses at night. While tobacco, pineapples, bearskins, and other goods were all targets of thievery, the most common transgression was stealing to drink. Many reports from the early 20th century detail dockers stealing bottles of brandy or gin and drinking rather than working. More often than not, the consequences were harsh. Five weeks of hard labour for one bottle of Hennessy brandy was not unheard of.[17]

These conditions eventually spurred Ben Tillett to lead the London Dock strike of 1889. The workers asked for only a minuscule increase in payment, but foremen initially refused. Over time the strike grew and eventually helped to draw attention to the poor conditions of London dockhands. The strike also revitalized the British Trades Union movement, leading to the betterment of labourers across London.[18]

Port industries

[edit]

Alongside the docks many port industries developed, some of which (notably sugar refining, edible oil processing, vehicle manufacture and lead smelting) survive today. Other industries have included iron working, casting of brass and bronze, shipbuilding, timber, grain, cement and paper milling, armament manufacture, etc. London dominated the world submarine communication cable industry for decades with works at Greenwich, Silvertown, North Woolwich, Woolwich and Erith.

For centuries London was the major centre of shipbuilding in Britain (for example at Blackwall Yard, London Yard, Samuda Yard, Millwall Iron Works, Thames Ironworks, Greenwich, and Deptford and Woolwich dockyards), but declined relative to the Clyde and other centres from the mid-19th century. This also affected an attempt by Henry Bessemer to establish steel-making on the Greenwich Peninsula in the 1860s.[19] The last major warship, HMS Thunderer, was launched in 1911.

The volume of shipping in the Port of London supported a very extensive ship repairing industry. In 1864, when most ships coming in were built of wood and powered by sail, there were 33 ship-repairing dry docks. The largest of these was Langley's Lower Dock at Deptford Green, which was 460 ft (140 m) in length. While the building of large ships ceased with the closure of the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company at Leamouth in 1912, the ship repairing trade continued to flourish. Although by 1930 the number of major dry docks had been reduced to 16, highly mechanised and geared to the repair of iron and steel-hulled ships.[20]

There were also numerous power stations and gas works on the Thames and its tributaries and canals. Major Thames-side gasworks were located at Beckton and East Greenwich, with power stations including Brimsdown, Hackney and West Ham on the River Lea and Kingston, Fulham, Lots Road, Wandsworth, Battersea, Bankside, Stepney, Deptford, Greenwich, Blackwall Point, Brunswick Wharf, Woolwich, Barking, Belvedere, Littlebrook, West Thurrock, Northfleet, Tilbury and Grain on the Thames.

The coal requirements of power stations and gas works constituted a large proportion of London's post-war trade. A 1959 Times article[21] states:

About two-thirds of the 20 million tons of coal entering the Thames each year is consumed in nine gas works and 17 generating stations. Beckton Gas Works carbonises an average of 4,500 tons of coal every day; the largest power stations burn about 3,000 tons during a winter day.. .. Three more power stations, at Belvedere (Oil-firing), and Northfleet and West Thurrock (coal-firing), are being built.

This coal was handled directly by riverside coal handling facilities, rather than the docks. For example, Beckton Gas Works had two large piers which dealt with both its own requirements and with the transfer of coal to lighters for delivery to other gasworks.

A considerable proportion of the drop in London's trade since the 1960s is accounted for by loss of the coal trade, the gas works having closed following discovery of North Sea gas, domestic use of coal for heating being largely replaced by gas and electricity, and closure of all the coal-burning power stations above Tilbury. In 2011, when Tilbury Power Station switched fully to burning biomass, London's coal imports fell to zero.[22]

The move downstream

[edit]

With the use of larger ships and containerisation, the importance of the upstream port declined rapidly from the mid-1960s. The enclosed docks further up river declined and closed progressively between the end of the 1960s and the early 1980s. Trade at privately owned wharves on the open river continued for longer, for example with container handling at the Victoria Deep Water Terminal on the Greenwich Peninsula into the 1990s, and bulk paper import at Convoy's Wharf in Deptford until 2000. The wider port continued to be a major centre for trade and industry, with oil and gas terminals at Coryton, Shell Haven and Canvey in Essex and the Isle of Grain in Kent. In 1992, the government privatisation policy led to Tilbury becoming a free port. The PLA then ceased to be a port operator, only retaining the role of managing the Thames.

Much of the disused land of the upstream is in the process of being developed for housing and the private financial estate of Canary Wharf.

The Port today

[edit]

The Port of London today comprises over 70 independently owned terminals and port facilities, directly employing over 30,000 people.[23] These are mainly concentrated at Purfleet (with the world's largest margarine works), Thurrock, Tilbury (the Port's current main container facility), London Gateway, Coryton and Canvey Island in Essex, Dartford and Northfleet in Kent, and Greenwich, Silvertown, Barking, Dagenham and Erith in Greater London.

The Port of London handles containers, timber, paper, vehicles, aggregates, crude oil, petroleum products, liquefied petroleum gas, coal, metals, grain and other dry and liquid bulk materials.

In 2012 London was the second largest port in the United Kingdom by tonnage handled (43.7 million), after Grimsby and Immingham (60 million).[24] The Port of London however handles the most non-fuel cargo of any port in the UK (at 32.2 million tonnes in 2007). Other major rival ports to London in the country are Felixstowe and Southampton, which handle the most and second-most number of containers of British ports; in 2012 London handled the third most and the Medway ports (chiefly London Thamesport) the fifth.[25]

The number of twenty-foot equivalent units of containers handled by the Port of London exceeded two million in 2007 for the first time in the Port's history and this continued in 2008. The Port's capacity in handling modern, large ships and containers is set to dramatically expand with the completion of the London Gateway port project, which will be able to handle up to 3.5 million TEUs per year when fully completed.

With around 12,500 commercial shipping movements annually, the Port of London handles around 10% of the UK commercial shipping trade, and contributes £8.5 billion to the UK's economy. In addition to cargo, 37 cruise ships visited the Port in 2008.

Once a major refiner of crude oil, today the port only imports refined products. The Kent (BP) and Shell Haven (Shell) refineries closed in 1982 and 1999, and Coryton in 2012. A number of upstream wharves remain in use. At Silvertown, for example, Tate & Lyle continues to operate the world's largest cane sugar refinery, originally served by the West India Docks but now with its own cargo handling facilities. Many wharves as far upstream as Fulham are used for the handling of aggregates brought by barge from facilities down river. Riverside sites in London are under intense pressure for prestige housing or office development, and as a consequence the Greater London Authority in consultation with the PLA has implemented a plan to safeguard 50 wharves, half above and half below the Thames Barrier.[26]

Intraport traffic

[edit]In recent years there has been a resurgence in the use of the River Thames for moving cargo between terminals within the Port of London. This is seen to be in the main part due to the environmental benefits of moving such cargo by river, and as an alternative to transporting the cargo on the congested road and rail networks of the capital. Local authorities are contributing to this increase in intraport traffic, with waste transfer and demolition rubble being taken by barges on the river. The construction of the Olympic Park and Crossrail both used the river as a means of transporting cargo and waste/excavation material, and the ongoing Thames Tideway Scheme also uses the river for these purposes, as well as for transporting of its Tunnel Boring Machines[27] as well as temporary offices.[28] The Crossrail project alone involved the transporting of 5 million tonnes of material, almost all of which is clean earth, excavated from the ground, downstream through the Port, from locations such as Canary Wharf to new nature reserves being constructed in the Thames estuary area.[29] This also includes the re-opening of wharves or jetties for various building projects along or near the Thames, Battersea coal jetty being the most recent.

In 2008, the figure for intraport trade was 1.9 million tonnes, making the River Thames the busiest inland waterway in the UK.

Expansion: London Gateway

[edit]DP World's London Gateway, opened in November 2013, is an expansion of the Port of London on the north bank of the Thames in Thurrock, Essex, 30 miles (48 km) east of central London. It is a fully integrated logistics facility, comprising a semi-automated, deep-sea container terminal on the same site as the UK's largest land bank for development of warehousing, distribution facilities and ancillary logistics services. It is a deep-water port able to handle the biggest container ships.

Policing the Port

[edit]The Port of London once had its own police force – the Port of London Authority Police – but is today policed by a number of forces. These are the local territorial police forces of the areas the Thames passes through (the Metropolitan, City of London, Essex and Kent forces) and the Port of Tilbury Police (formed in 1992 and a remnant of the old PLA force). The Metropolitan police have a special Marine Support Unit, formerly known as the Thames Division, which patrol and police the Thames in the Greater London area. A sixth police force in the Port may be established with the creation of the London Gateway port.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schedule 1 of the Port of London Act 1968

- ^ Section 213 of the Port of London Act 1968, as amended

- ^ "All freight tonnage traffic by port and year" (.ods, OpenDocument spreadsheet). Department for Transport. 14 July 2021.New data appended annually.

- ^ "Enforcement Action". Port of London Authority. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "PLA Drying Out Facilities". Port of London Authority. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ *Brigham, Trevor. 1998. "The Port of Roman London." In Roman London Recent Archeological Work, edited by B. Watson, 23–34. Michigan: Cushing-Malloy Inc. Paper read at a seminar held at The Museum of London, 16 November.

- ^ Milne, Gustav, and Nic Bateman. "A Roman Harbour in London; Excavations and Observations near Pudding Lane, City of London 1979–82." Britannia 14 (1983): 207–26

- ^ Milne, Gustav. The Port of Roman London. London: B.T. Batsford, 1985 (Milne)

- ^ "New tales of old London: the lost Roman port, Shadwell, and other stories". www.layersoflondon.org.

- ^ Hall, Jenny, and Ralph Merrifield. Roman London. London: HMSO Publications, 1986 (Hall & Merrifield)

- ^ a b Museum of London. "Museum of London Docklands". Museumindocklands.org.uk. Archived from the original on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "The West India Docks: Introduction, Survey of London: volumes 43 and 44: Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs (1994), pp. 247–248. Date accessed: 16 April 2010". British-history.ac.uk. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Clout, H. (Ed) 1994, The Times London History Atlas, Times Books, ISBN 0-7230-0342-4

- ^ Mowlem 1822 – 1972, p.8

- ^ Lovell, John (1969). Stevedores and Dockers: A Study of Trade Unionism in the Port of London, 1870–1914. London: Macmillan. p. 19. ISBN 9780333013519.

- ^ Schneer, Jonathan (1999). London 1900: The Imperial Metropolis. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 43.

- ^ Schneer, Jonathan (1999). London 1900: The Imperial Metropolis. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 47.

- ^ Royal Museums Greenwich. "The Great Dock Strike of 1889". Port Cities London.

- ^ "Bessemer's autobiography Chapter 21". History.rochester.edu. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Dockland Life: A Pictorial History of London's Docks, 1860–1970 by Chris Ellmers and Alex Werner, Mainstream Publishing Company, Edinburgh, 1995, ISBN 1-85158-364-5

- ^ Special Correspondent (16 March 1959). "Industries along the Riverside". news. The Times. No. 54410. London. col. A, p. xi.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Port of London 2011 Trade Stable". Port of London Authority. 13 February 2011. Archived from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Port of London Economic Impact Study". Port of London Authority. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ "Statistical data set PORT01 – UK ports and traffic". Department for Transport.

- ^ "Port Freight Statistics: Provisional Annual 2012" (PDF). Department for Transport.

- ^ "London Plan Implementation Report: Safeguarded Wharves on the River Thames" (PDF). Mayor of London. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ Thames Tideway Project press release https://www.tideway.london/news/media-centre/rachel-rolls-up-the-river/

- ^ Tideway. "River freight marks the arrival of Tideway in Bermondsey – Tideway – Reconnecting London with the River Thames".

- ^ PLA News Crossrail will move 5m tonnes via River Archived 4 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine