Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Slurry ice

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (November 2014) |

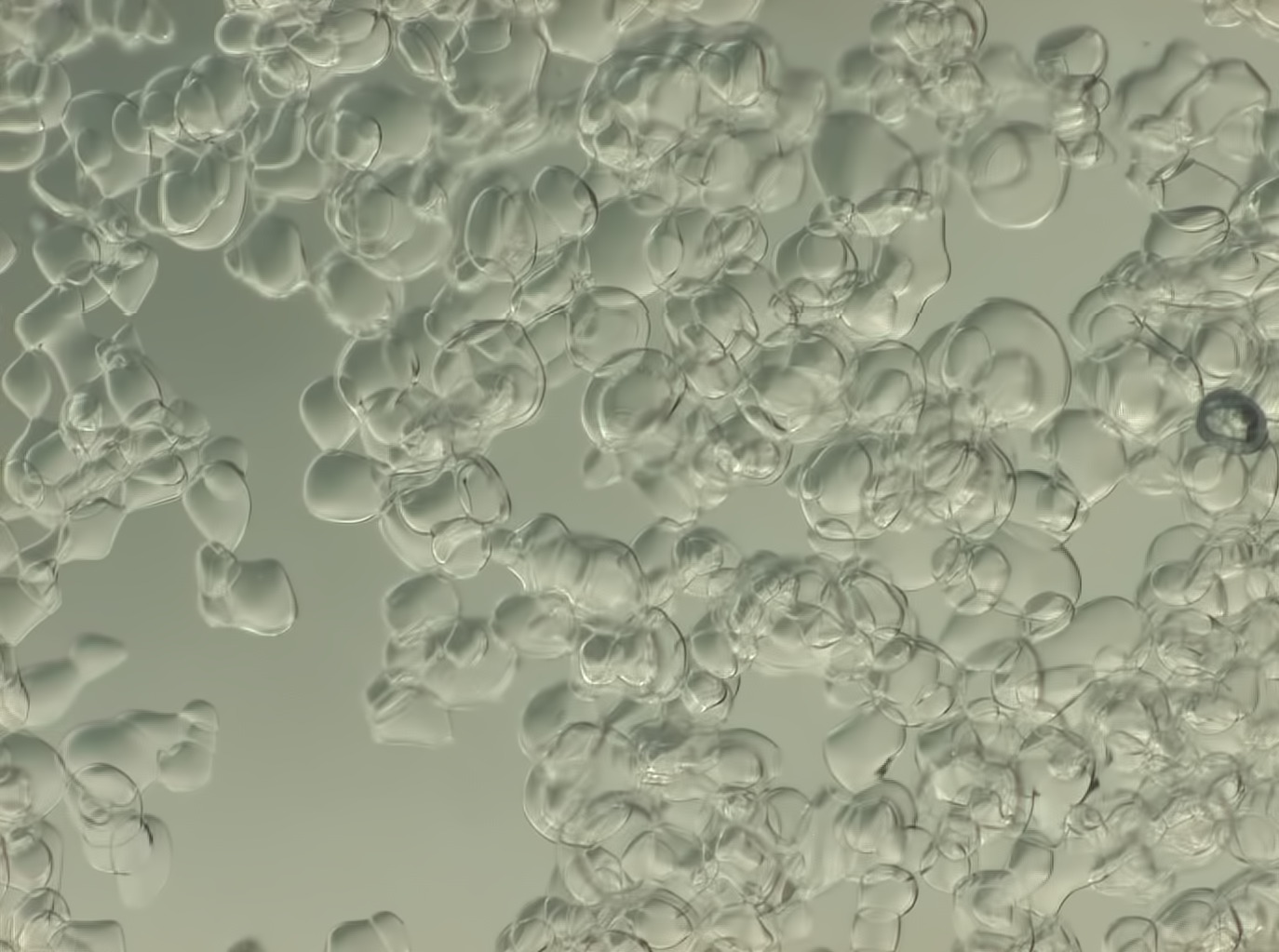

Slurry ice is a phase changing refrigerant made up of millions of ice "micro-crystals" (typically 0.1 to 1 mm in diameter) formed and suspended within a solution of water and a freezing point depressant. Some compounds used in the field are salt, ethylene glycol, propylene glycol, alcohols like isobutyl and ethanol, and sugars like sucrose and glucose. Slurry ice has greater heat absorption compared to single phase refrigerants like brine, because the melting enthalpy (latent heat) of the ice is also used.

Characteristics

[edit]The small ice particle size results in greater heat transfer area than other types of ice for a given weight. It can be packed inside a container as dense as 700 kg/m3, the highest ice-packing factor among all usable industrial ice.

The spherical crystals have good flow properties, making them easy to distribute through conventional pumps and piping and over product in direct contact chilling applications, allowing them to flow into crevices and provide greater surface contact and faster cooling than other traditional forms of ice (flake, block, shell, etc.).

Its flow properties, high cooling capacity, and flexibility in application make a slurry ice system a substitute for conventional ice generators and refrigeration systems, and offers improvements in energy efficiency: 70%, compared to around 45% in standard systems, lower freon consumption per ton of ice, and lower operating costs.

Application fields

[edit]Slurry ice is commonly used in a wide range of air conditioning, packaging, and industrial cooling processes, supermarkets, and cooling and storage of fish, produce, poultry and other perishable products.

Slurry ice can boost by up to 200% the cooling efficiency of existing cooling or freezing brine systems without any major changes to the system (i.e. heat exchanger, pipes, valves), and reduce the amount of energy consumption used for pumping.

Advantages

[edit]Slurry ice is also used in direct contact cooling of products in food processing applications in water resistant shipping containers. It provides the following advantages:

- Product is cooled faster – the smooth round shape of the small crystals ensures maximum surface area contact with the product and as a result, faster heat transfer.

- Better product protection – the smooth, round crystals do not damage product, unlike other forms of sharp, jagged ice (flake, block, shell, etc.).

- Even cooling – unlike other irregular shaped ice which mostly conducts heat through the air, the round shape of the slurry crystals enables them to flow freely around the entire product, filling all air pockets to uniformly maintain direct contact and the desired low temperature.

Slurry ice generators

[edit]Slurry ice is generated using a unique type of ice-making technology. Conventional ice generators produce sharp edged, dry ice fragments, not the small, spherical crystals found in slurry ice. In traditional brine chiller systems, crystals forming inside the solution would block or damage the system.

Scraped surface generators

[edit]The world’s first patent for a slurry ice generator was filed by Sunwell Technologies Inc. of Canada in 1976. Sunwell Technologies Inc. introduced slurry ice under the trade name deepchill ice, in the late 1970s. Slurry ice is created through a process of forming spherical ice crystals within a liquid. The slurry ice generator is a scraped-surface vertical shell and tube heat exchanger. It consists of concentric tubes with refrigerant flowing between them and the water/freezing point depressant solution in the inner tube. The inner surface of the inner tube is wiped using a mechanism which in the original Sunwell design consists of a central shaft, spring-loaded plastic blades, bearings, and seals. The small ice crystals formed in the solution near the tube surface are wiped away from the surface and mixed with unfrozen water, forming the slurry. Other slurry ice generators adapted the first idea of wiping the surface using an auger originally designed to create flake ice. Wipers also can be brushes or fluidized bed heat exchangers for ice crystallization. In these heat exchangers, steel particles circulate with the fluid, mechanically removing the crystals from the surface. At the outlet, steel particles and slurry ice are separated.

Direct contact generators

[edit]An immiscible primary refrigerant evaporates to supersaturate the water and form small, smooth crystals. With direct contact chilling, there is no physical boundary between the brine and the refrigerant, increasing the rate of heat transfer. However, the major disadvantage of this system is that a small amount of refrigerant stays in the brine, trapped in the crystals. This refrigerant is pumped with the slurry out of the generator and into the environment.

Supercooling generators

[edit]Pure water is supercooled in a chiller to −2°C and released through a nozzle into a storage tank. Upon release, it undergoes a phase transition, forming small ice particles with 2.5% ice fraction. In the storage tank, it is separated by the difference in density between ice and water. The cold water is supercooled and released again, increasing the ice fraction in the storage tank. However, a small crystal in the supercooled water or a nucleation cell on the surface will act as a seed for ice crystals and block the generator.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Michael Kauffeld, Masahiro Kawaji, Peter W. Egolf. Handbook on Ice Slurries. IIR ISBN 2-913149-44-8

- Delft University of Technologies (NL)