Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

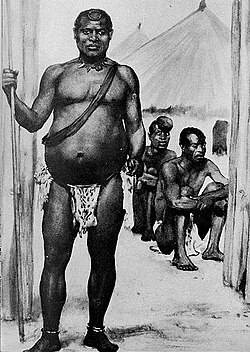

Lobengula

View on Wikipedia

Lobengula Khumalo (c. 1835 – c. 1894) was the second and last official king of Mthwakazi (historically called Matabeleland in English). Both names in the Ndebele language mean "the men of the long shields", a reference to the Ndebele warriors' use of the Nguni shield.

Key Information

Background

[edit]The Matabele were descendants of a faction of the Zulu people who fled Transvaal in South Africa after the Boers invaded the area running away from the English in the Cape Colony. Mzilikazi settled in Transvaal after running away from Shaka in KwaZulu-Natal. Shaka's military, Mzilikazi led his followers away from Zulu territory after a falling-out. In the late 1830s, they settled in Transvaal. He was ruthless and he pillaged and slaughtered, Mzilikazi rounded up the strong men and women, turning the men into army recruits and the women into concubines for his warriors, his possessions increasing with his power and prestige, and his followers numbering, in due course, more Sotho youths than Zulu. He made himself a king of the Transvaal area. Between 1827 and 1832, Mzilikazi built himself three military strongholds. The largest was Kungwini, situated at the foot of the Wonderboom Mountains on the Apies River, just north of present day Pretoria. Another was Dinaneni, north of the Hartbeespoort Dam, while the third was Hlahlandlela in the territory of the Fokeng near Rustenburg.

Members of the tribe had a privileged position against outsiders whose lives were subject to the will of the king. In return for their privileges, however, the Ndebele people both men and women had to submit to a strict discipline and status within the hierarchy. That set out their duties and responsibilities to the rest of society. Infringements of any social responsibility were punished with death, subject to the king's seldom-awarded reprieve. This tight discipline and loyalty were the secret of the Ndebele's success in dominating their neighbours.[2]

Birthright

[edit]After the death of Mzilikazi, the first king of the Ndebele nation, in 1868, the izinduna, or chiefs, offered the crown to Lobengula, one of Mzilikazi's sons from an inferior wife. Several impis (regiments) led by Chief Mbiko Masuku disputed Lobengula's ascent, and the question was ultimately decided by the arbitration of the assegai, with Lobengula and his impis crushing the rebels. Lobengula's courage in the battle led to his unanimous selection as king.[who?]

Coronation

[edit]The coronation of Lobengula took place at Mhlahlandlela, one of the principal military towns. The Ndebele nation assembled in the form of a large semicircle, performed a war dance, and declared their willingness to fight and die for Lobengula. A great number of cattle were slaughtered, and the choicest meats were offered to Mlimo, the Ndebele spiritual leader, and to the dead Mzilikazi. Great quantities of millet beer were also consumed.

About 10,000 Matabele warriors in full war costume attended the crowning of Lobengula. Their costumes consisted of a headdress and short cape made of black ostrich feathers, a kilt made of leopard or other skins and ornamented with the tails of white cattle. Around their arms they wore similar tails and around their ankles they wore rings of brass and other metals. Their weapons consisted of one or more long spears for throwing and a short stabbing-spear or assegai (also the principal weapon of the Zulu people). For defence, they carried large oval shields of ox-hide, either black, white, red, or speckled according to the impi (regiment) they belonged to.

The Ndebele maintained their position due to the greater size and tight discipline in the army, to which every able-bodied man in the tribe owed service. "The Ndebele army, consisting of 15,000 men in 40 regiments [was] based around Lobengula's capital of Bulawayo."[3]

— Lobengula[4]

Rule

[edit]In 1870 King Lobengula granted Sir John Swinburne's London and Limpopo Mining Company the right to search for gold and other minerals on a tract of land in the extreme southwest of Matabeleland along the Tati River between the Shashe and Ramaquabane rivers, in what became known as the Tati Concession.[5][6] However, it was not until about 1890 that any significant mining in the area commenced.[citation needed]

Lobengula had been tolerant of the white hunters who came to Matabeleland; he would even go so far as to punish those of his tribe who threatened the whites. However, when a British team (Francis Thompson, Charles Rudd and Rochfort Maguire) came in 1888 to try to persuade him to grant them the right to dig for minerals in additional parts of his territory, he was wary about entering into negotiations. Lobengula gave his agreement only when his friend, Leander Starr Jameson, a qualified medical doctor who had once treated Lobengula for gout, proposed to secure money and weaponry for the Matabele in addition to a pledge that any people who came to dig would be considered as living in his kingdom. As part of this agreement, and at the insistence of the British, neither the Boers nor the Portuguese would be permitted to settle or gain concessions in Matabeleland. Although, Lobengula was illiterate and was not aware of how damaging this contract was to his country, only found out the real terms of the contract he signed as his subjects found out. After going to friendly English missionaries to confirm this rumor, Lobengula sent two emissaries to the British queen, Victoria, but this proved futile. They were delayed by Alfred Beit's associates at the port. As a last resort, Lobengula formally protested the contract to the queen on 23 April 1889. As a response from the queen's advisor, Lobengula was told it was "impossible for them to exclude white men". Lobengula informed Queen Victoria he and his Indunas would recognize the contract as they believe he was tricked. The 25-year Rudd Concession was signed by Lobengula on 30 October 1888.[7][8]

Matabele War

[edit]The First Matabele War began in October 1893, and the British South Africa Company's overwhelming military force led to devastating losses for the Ndebele warriors, notably at the Battle of the Shangani. As early as December 1893, it was reported that Lobengula had been very sick, but his death sometime in early 1894 was kept a secret for many months, and the cause of his death remains uncertain.[9][10]

By October 1897, the white colonists had successfully settled in much of the territory known later as Rhodesia.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]He had well over 20 wives, possibly many more; among them were Xwalile, daughter of king Mzila of the Gaza Empire, and Lozikeyi.

Lobengula had 3 sons born from first wife Mamkhwananzi and her niece (Mamkwananzi) (inhlanzi). The first Mamkwananzi had sons Nyamande and the young Mamkhwananzi and Sintinga had a son called Umhlambi. He also had other sons from another wife, Njube, Nguboyenja, Mpezeni and Sidojiwe. Lobengula's oldest son was called Mankisimani, however not much is recorded about him because there is no dispute that he was born before Lobengula was a king so was not eligible to be an heir to the throne.

Lobengula's 3 sons Njube, Nguboyenja and Mpezeni we sent to South Africa to pursue education by the colonial leaders. It is believed that Nguboyenja and Mpezeni died without any male children. Njube however, had sons Albert and Rhodes who are known to be the founders of Highlanders Football club in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Cobbing 1976, p. 1.

- ^ Dodds 1998.

- ^ Meredith 2008, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Parsons 1993.

- ^ Galbraith 1974, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Quick 2001, pp. 27–39.

- ^ "The Rudd Concession (ca. 1888)". pamusoroi.com. 13 October 1888. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ Perry, Marvin (2012–2014). Sources of the Western tradition Volume II: from the Renaissance to the Present (Ninth ed.). Boston. ISBN 9781133935285.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "LOBENGULA IN A TRAP.; Not Believed that the Matabele King Can Escape". The New York Times. 3 November 1893. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ "SOUTH AFRICA: The Skull of Lobengula". Time. 10 January 1944. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ Sheldon 2005.

Sources

[edit]- Burnham, Frederick Russell (1926). Scouting on Two Continents. Doubleday, Page.

- Cobbing, Julian (1976). "Introduction". The Ndebele Under the Khumalos, 1820–1896 (Doctoral). University of Lancaster.

- Dodds, Glen Lyndon (1998). The Zulus and Matabele: Warrior Nations. Arms and Armour. ISBN 978-1-85409-381-3.

- Galbraith, John S. (1974). Crown and Charter: The Early Years of the British South Africa Company. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02693-3.

- Hensman, Howard (1900). A History of Rhodesia (PDF). W. Blackwood and Sons.

- Meredith, Martin (2008). Diamonds, Gold, and War: The British, the Boers, and the Making of South Africa. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-677-8.

- Parsons, Neil (1993). A New History of Southern Africa (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 978-0-8419-5319-2.

- Quick, Geoffrey S. (2001). "Early European involvement in the Tati District". Botswana Notes and Records. 33: 27–39. JSTOR 40980293.

- Sheldon, Kathleen E. (2005). Historical Dictionary of Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5331-7.

- Wills, W. A.; Collingridge, L. T. (1894). The Downfall of Lobengula: The Cause, History, and Effect of the Matabeli War. The African Review.