Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Desipramine

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Norpramin, Pertofrane, others |

| Other names | Desmethylimipramine; Norimipramine; EX-4355; G-35020; JB-8181; NSC-114901[1][2][3] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682387 |

| Routes of administration | Oral, intramuscular injection |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60–70%[5] |

| Protein binding | 91%[5] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6)[6] |

| Elimination half-life | 12–30 hours[5] |

| Excretion | Urine (70%), feces[5] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.037 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H22N2 |

| Molar mass | 266.388 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Desipramine, sold under the brand name Norpramin among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) used in the treatment of depression.[7] It acts as a relatively selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, though it does also have other activities such as weak serotonin reuptake inhibitory, α1-blocking, antihistamine, and anticholinergic effects. The drug has not been considered a first-line treatment for depression since the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants, which have fewer side effects and are safer in overdose.

Medical uses

[edit]Desipramine is primarily used for the treatment of depression.[7] It may also be useful to treat symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[8] Evidence of benefit is only in the short term, and with concerns of side effects its overall usefulness is not clear.[9] Desipramine at very low doses is also used to help reduce the pain associated with functional dyspepsia.[10] It has also been tried, albeit with little evidence of effectiveness, in the treatment of cocaine dependence.[11] Evidence for usefulness in neuropathic pain is also poor.[12]

Side effects

[edit]Desipramine tends to be less sedating than other TCAs and tends to produce fewer anticholinergic effects such as dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, blurred vision, and cognitive or memory impairments.[13]

Overdose

[edit]Desipramine is particularly toxic in cases of overdose, compared to other antidepressants.[14] Any overdose or suspected overdose of desipramine is considered to be a medical emergency and can result in death without prompt medical intervention.

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 17.6–163 | Human | [16][17] |

| NET | 0.63–3.5 | Human | [16][17] |

| DAT | 3,190 | Human | [16] |

| 5-HT1A | ≥6,400 | Human | [18][19] |

| 5-HT2A | 115–350 | Human | [18][19] |

| 5-HT2C | 244–748 | Rat | [20][21] |

| 5-HT3 | ≥2,500 | Rodent | [21][22] |

| 5-HT7 | >1,000 | Rat | [23] |

| α1 | 23–130 | Human | [18][24][17] |

| α2 | ≥1,379 | Human | [18][24][17] |

| β | ≥1,700 | Rat | [25][26] |

| Cav2.2 | 410 | Human | [27] |

| D1 | 5,460 | Human | [28] |

| D2 | 3,400 | Human | [18][24] |

| H1 | 60–110 | Human | [18][24][29] |

| H2 | 1,550 | Human | [29] |

| H3 | >100,000 | Human | [29] |

| H4 | 9,550 | Human | [29] |

| mACh | 66–198 | Human | [18][24] |

| M1 | 110 | Human | [30] |

| M2 | 540 | Human | [30] |

| M3 | 210 | Human | [30] |

| M4 | 160 | Human | [30] |

| M5 | 143 | Human | [30] |

| σ1 | 1,990–4,000 | Rodent | [31][32] |

| σ2 | ≥1,611 | Rat | [15][32] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Desipramine is a very potent and relatively selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI), which is thought to enhance noradrenergic neurotransmission.[33][34] Based on one study, it has the highest affinity for the norepinephrine transporter (NET) of any other TCA,[16] and is said to be the most noradrenergic[35] and the most selective for the NET of the TCAs.[33] The observed effectiveness of desipramine in the treatment of ADHD was the basis for the development of the selective NRI atomoxetine and its use in ADHD.[33]

Desipramine has the weakest antihistamine and anticholinergic effects of the TCAs.[36][35][37] It tends to be slightly activating/stimulating rather than sedating, unlike most others TCAs.[35] Whereas other TCAs are useful for treating insomnia, desipramine can cause insomnia as a side effect due to its activating properties.[35] The drug is also not associated with weight gain, in contrast to many other TCAs.[35] Secondary amine TCAs like desipramine and nortriptyline have a lower risk of orthostatic hypotension than other TCAs,[38][39] although desipramine can still cause moderate orthostatic hypotension.[40]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Desipramine is the major metabolite of imipramine and lofepramine.[41]

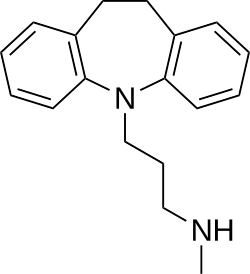

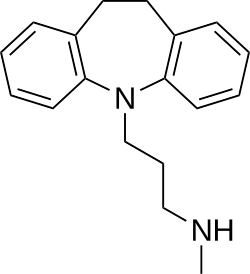

Chemistry

[edit]Desipramine is a tricyclic compound, specifically a dibenzazepine, and possesses three rings fused together with a side chain attached in its chemical structure.[42] Other dibenzazepine TCAs include imipramine (N-methyldesipramine), clomipramine, trimipramine, and lofepramine (N-(4-chlorobenzoylmethyl)desipramine).[42][43] Desipramine is a secondary amine TCA, with its N-methylated parent imipramine being a tertiary amine.[44][45] Other secondary amine TCAs include nortriptyline and protriptyline.[46][47] The chemical name of desipramine is 3-(10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,f]azepin-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine and its free base form has a chemical formula of C18H22N2 with a molecular weight of 266.381 g/mol.[1] The drug is used commercially mostly as the hydrochloride salt; the dibudinate salt is or has been used for intramuscular injection in Argentina (brand name Nebril) and the free base form is not used.[1][2] The CAS Registry Number of the free base is 50-47-5, of the hydrochloride is 58-28-6, and of the dibudinate is 62265-06-9.[1][2][48]

History

[edit]Desipramine was developed by Geigy.[49] It first appeared in the literature in 1959 and was patented in 1962.[49] The drug was first introduced for the treatment of depression in 1963 or 1964.[49][50]

Society and culture

[edit]Generic names

[edit]Desipramine is the generic name of the drug and its INN and BAN, while desipramine hydrochloride is its USAN, USP, BAN, and JAN.[1][2][51][3] Its generic name in French and its DCF are désipramine, in Spanish and Italian and its DCIT are desipramina, in German is desipramin, and in Latin is desipraminum.[2][3]

Brand names

[edit]Desipramine is or has been marketed throughout the world under a variety of brand names, including Irene, Nebril, Norpramin, Pertofran, Pertofrane, Pertrofran, and Petylyl among others.[2][3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 363–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 304–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ a b c d "Desipramine - Drugs.com". drugs.com.

- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ a b c d Lemke TL, Williams DA (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 588–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0.

- ^ Sallee FR, Pollock BG (May 1990). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of imipramine and desipramine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 18 (5): 346–364. doi:10.2165/00003088-199018050-00002. PMID 2185906. S2CID 37529573.

- ^ a b Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ Ghanizadeh A (July 2013). "A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of desipramine for treating ADHD". Current Drug Safety. 8 (3): 169–174. doi:10.2174/15748863113089990029. PMID 23914752.

- ^ Otasowie J, Castells X, Ehimare UP, Smith CH (September 2014). "Tricyclic antidepressants for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (9) CD006997. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006997.pub2. PMC 11236426. PMID 25238582.

- ^ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com.

- ^ Pani PP, Trogu E, Vecchi S, Amato L (December 2011). "Antidepressants for cocaine dependence and problematic cocaine use". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12) CD002950. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002950.pub3. PMC 12277681. PMID 22161371.

- ^ Hearn L, Moore RA, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Phillips T (September 2014). Hearn L (ed.). "Desipramine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (9) CD011003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011003.pub2. PMC 6804291. PMID 25246131.

- ^ "Desipramine Hydrochloride". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ White N, Litovitz T, Clancy C (December 2008). "Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 4 (4): 238–250. doi:10.1007/BF03161207. PMC 3550116. PMID 19031375.

- ^ a b Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (December 1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". European Journal of Pharmacology. 340 (2–3): 249–258. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ^ a b c d Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, Nemeroff CB (December 1997). "Neurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of antidepressants and their metabolites". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 283 (3): 1305–1322. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(24)37161-7. PMID 9400006.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E (May 1994). "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology. 114 (4): 559–565. doi:10.1007/bf02244985. PMID 7855217. S2CID 21236268.

- ^ a b Wander TJ, Nelson A, Okazaki H, Richelson E (December 1986). "Antagonism by antidepressants of serotonin S1 and S2 receptors of normal human brain in vitro". European Journal of Pharmacology. 132 (2–3): 115–121. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90596-0. PMID 3816971.

- ^ Pälvimäki EP, Roth BL, Majasuo H, Laakso A, Kuoppamäki M, Syvälahti E, Hietala J (August 1996). "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the serotonin 5-HT2c receptor". Psychopharmacology. 126 (3): 234–240. doi:10.1007/bf02246453. PMID 8876023. S2CID 24889381.

- ^ a b Toll L, Berzetei-Gurske IP, Polgar WE, Brandt SR, Adapa ID, Rodriguez L, et al. (March 1998). "Standard binding and functional assays related to medications development division testing for potential cocaine and opiate narcotic treatment medications". NIDA Research Monograph. 178: 440–466. PMID 9686407.

- ^ Schmidt AW, Hurt SD, Peroutka SJ (November 1989). "'[3H]quipazine' degradation products label 5-HT uptake sites". European Journal of Pharmacology. 171 (1): 141–143. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90439-1. PMID 2533080.

- ^ Shen Y, Monsma FJ, Metcalf MA, Jose PA, Hamblin MW, Sibley DR (August 1993). "Molecular cloning and expression of a 5-hydroxytryptamine7 serotonin receptor subtype". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (24): 18200–18204. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)46830-X. PMID 8394362.

- ^ a b c d e Richelson E, Nelson A (July 1984). "Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 230 (1): 94–102. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(25)21446-X. PMID 6086881.

- ^ Muth EA, Haskins JT, Moyer JA, Husbands GE, Nielsen ST, Sigg EB (December 1986). "Antidepressant biochemical profile of the novel bicyclic compound Wy-45,030, an ethyl cyclohexanol derivative". Biochemical Pharmacology. 35 (24): 4493–4497. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(86)90769-0. PMID 3790168.

- ^ Sánchez C, Hyttel J (August 1999). "Comparison of the effects of antidepressants and their metabolites on reuptake of biogenic amines and on receptor binding". Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 19 (4): 467–489. doi:10.1023/A:1006986824213. PMC 11545528. PMID 10379421. S2CID 19490821.

- ^ Benjamin ER, Pruthi F, Olanrewaju S, Shan S, Hanway D, Liu X, et al. (September 2006). "Pharmacological characterization of recombinant N-type calcium channel (Cav2.2) mediated calcium mobilization using FLIPR". Biochemical Pharmacology. 72 (6): 770–782. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.003. PMID 16844100.

- ^ Deupree JD, Montgomery MD, Bylund DB (December 2007). "Pharmacological properties of the active metabolites of the antidepressants desipramine and citalopram". European Journal of Pharmacology. 576 (1–3): 55–60. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.08.017. PMC 2231336. PMID 17850785.

- ^ a b c d Appl H, Holzammer T, Dove S, Haen E, Strasser A, Seifert R (February 2012). "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H₁R, H₂R, H₃R, and H₄R receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 385 (2): 145–170. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803. S2CID 14274150.

- ^ a b c d e Stanton T, Bolden-Watson C, Cusack B, Richelson E (June 1993). "Antagonism of the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in CHO-K1 cells by antidepressants and antihistaminics". Biochemical Pharmacology. 45 (11): 2352–2354. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90211-e. PMID 8100134.

- ^ Weber E, Sonders M, Quarum M, McLean S, Pou S, Keana JF (November 1986). "1,3-Di(2-[5-3H]tolyl)guanidine: a selective ligand that labels sigma-type receptors for psychotomimetic opiates and antipsychotic drugs". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (22): 8784–8788. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.8784W. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.22.8784. PMC 387016. PMID 2877462.

- ^ a b Hindmarch I, Hashimoto K (April 2010). "Cognition and depression: the effects of fluvoxamine, a sigma-1 receptor agonist, reconsidered". Human Psychopharmacology. 25 (3): 193–200. doi:10.1002/hup.1106. PMID 20373470. S2CID 26491662.

- ^ a b c Martin A, Volkmar FR, Lewis M (2007). Lewis's Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 764–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6214-4.

- ^ Janowsky DS, Byerley B (October 1984). "Desipramine: an overview". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 45 (10 Pt 2): 3–9. PMID 6384207.

- ^ a b c d e Curtin C (19 January 2016). Pain Management, An Issue of Hand Clinics, E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-0-323-41691-7.

- ^ Gold MS, Carman JS, Lydiard RB (2 July 1984). Advances in Psychopharmacology. CRC Press. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-0-8493-5680-3.

- ^ Bayless TM, Diehl A (2005). Advanced Therapy in Gastroenterology and Liver Disease. PMPH-USA. pp. 263–. ISBN 978-1-55009-248-6.

- ^ Leigh H (6 December 2012). Biopsychosocial Approaches in Primary Care: State of the Art and Challenges for the 21st Century. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-1-4615-5957-3.

- ^ Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Gabbard GO (2011). Essentials of Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 468–. ISBN 978-1-58562-933-6.

- ^ Rakel RE (May 2007). Textbook of Family Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 313–. ISBN 978-1-4377-2190-4.

- ^ Leonard BE (October 1987). "A comparison of the pharmacological properties of the novel tricyclic antidepressant lofepramine with its major metabolite, desipramine: a review". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2 (4): 281–297. doi:10.1097/00004850-198710000-00001. PMID 2891742.

- ^ a b Ritsner MS (15 February 2013). Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice, Volume I: Multiple Medication Use Strategies. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-94-007-5805-6.

- ^ Lemke TL, Williams DA (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 580–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5.

- ^ Cutler NR, Sramek JJ, Narang PK (20 September 1994). Pharmacodynamics and Drug Development: Perspectives in Clinical Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-471-95052-3.

- ^ Anzenbacher P, Zanger UM (23 February 2012). Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-3-527-64632-6.

- ^ Anthony PK (2002). Pharmacology Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-56053-470-9.

- ^ Cowen P, Harrison P, Burns T (9 August 2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. OUP Oxford. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-0-19-162675-3.

- ^ Chambers M. "Desipramine dibudinate". ChemIDplus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c Andersen J, Kristensen AS, Bang-Andersen B, Strømgaard K (July 2009). "Recent advances in the understanding of the interaction of antidepressant drugs with serotonin and norepinephrine transporters". Chemical Communications (25): 3677–3692. doi:10.1039/b903035m. PMID 19557250.

- ^ Dart RC (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 836–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ^ Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

External links

[edit]Desipramine

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Description and Classification

Desipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) primarily used in the management of major depressive disorder. It serves as the active metabolite of imipramine, another TCA, formed through hepatic metabolism via cytochrome P450 enzymes such as CYP2C19.[7][8] Chemically, desipramine is classified as a dibenzazepine derivative, characterized by its tricyclic structure consisting of two benzene rings fused to a central azepine ring, along with a secondary amine side chain that contributes to its pharmacological profile.[7][9] Tricyclic antidepressants as a class emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, evolving from antihistamine and antipsychotic research; imipramine, the prototype TCA, was approved by the FDA in 1959 for depression treatment, paving the way for subsequent agents like desipramine.[10][11] A key distinguishing feature of desipramine among TCAs is its selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibition (NRI), exhibiting approximately 400-fold greater potency in blocking norepinephrine transporters compared to serotonin transporters, resulting in minimal serotonergic effects relative to other TCAs like clomipramine.[12] In contemporary therapeutic positioning, desipramine is not regarded as a first-line option for depression due to its adverse effect profile, including anticholinergic and cardiovascular risks, but it remains relevant for treatment-resistant cases where selective noradrenergic enhancement may provide benefit.[13][14]Therapeutic Role

Desipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) with selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, serves as a secondary option in modern psychiatric treatment for major depressive disorder, particularly when first-line agents like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) fail to achieve remission. While SSRIs and SNRIs are favored for their lower risk of cardiac toxicity and overdose, desipramine may offer advantages in melancholic depression, where it has demonstrated efficacy at plasma concentrations around 115 ng/mL, addressing core symptoms such as anhedonia and psychomotor disturbances more effectively than placebo.[1][15] Its norepinephrine-centric action also aligns with the needs of patients experiencing atypical or anergic depression, characterized by low energy, hypersomnia, and increased appetite, potentially providing targeted symptomatic relief in these subtypes.[1][16] In treatment algorithms for depression, desipramine is typically positioned as a third-line intervention following inadequate response to SSRIs or SNRIs, with particular utility in refractory cases or when comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is present, as it leads to response in approximately 68% of adults while treating depressive features.[1][17] Meta-analyses from the 2010s confirm TCAs' efficacy comparable to each other for acute depression treatment, though they show higher dropout rates than SSRIs like fluoxetine due to side effects.[18] Relative to amitriptyline, another TCA, desipramine exhibits improved tolerability with reduced sedation and anticholinergic burden, making it a preferable choice within its class for patients sensitive to these effects.[19] Despite these roles, desipramine's use is tempered by significant limitations, including a black box warning from the FDA highlighting an increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults under 25 during initial treatment phases.[5] It is generally avoided in elderly patients owing to heightened risks of falls from orthostatic hypotension and confusional states, with guidelines recommending lower doses or alternatives in this population.[20] American Psychiatric Association guidelines reinforce TCAs like desipramine for treatment-resistant depression but emphasize their role only after optimizing first- and second-line therapies, underscoring ongoing concerns about safety in vulnerable groups.[21]Medical Applications

Approved Indications

Desipramine, marketed as Norpramin, received FDA approval in 1964 as a tricyclic antidepressant for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults.[22][1] Clinical trials from the 1960s and 1970s established its efficacy, with response rates typically ranging from 50% to 60% in reducing symptoms as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). For instance, meta-analyses of tricyclic antidepressants, including desipramine, have shown that 56% to 60% of patients achieve significant improvement compared to 42% to 47% on placebo.[23] Systematic reviews, such as those evaluating tricyclic antidepressants for depression, confirm desipramine's comparable efficacy to other antidepressants in adults, though it is now considered a second-line option due to side effect profiles.[24] Although desipramine has been investigated for pediatric applications like enuresis and ADHD, current FDA labeling specifies it is not approved for use in children, with safety and effectiveness not established in this population. Recent pediatric guidelines from the 2020s emphasize behavioral therapies as first-line for enuresis, limiting pharmacological options like tricyclics to refractory cases under specialist supervision.[5][25]Off-Label and Investigational Uses

Desipramine has been explored off-label for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in both children and adults, leveraging its noradrenergic effects to improve core symptoms such as inattention and hyperactivity. Small randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in children and adolescents have demonstrated efficacy, with desipramine showing benefits comparable to stimulants in reducing ADHD symptoms as rated by teachers and physicians.[26] However, the use of desipramine for treating ADHD in children became controversial in the early 1990s due to reports of rare sudden cardiac deaths in a small number of children, even at normal therapeutic doses. These incidents, including cases reported in 1990 and subsequent years, prompted the FDA to issue warnings and led to a significant reduction in its pediatric use.[27][5] In adults, it is used off-label when first-line stimulants are ineffective or contraindicated, though evidence is derived from smaller studies and expert consensus rather than large-scale trials.[28] A 2013 systematic review confirmed desipramine's role among tricyclic antidepressants as effective for ADHD, particularly in pediatric populations, based on controlled trials.[29] Desipramine has also been used off-label for bulimia nervosa, where controlled studies have shown significant reductions in binge-eating frequency (e.g., 91% decrease compared to placebo in a double-blind trial). Evidence from systematic reviews supports tricyclic antidepressants like desipramine for reducing bulimic symptoms, though it is considered second-line due to side effects.[1][30] Another off-label application is in neuropathic pain, particularly diabetic neuropathy, where low doses (typically 25-75 mg/day) have shown symptom reduction in 1990s studies. A double-blind RCT comparing desipramine to placebo and clomipramine in diabetic neuropathy patients found significant improvements in pain scores via observer and self-ratings.[31] However, a 2014 Cochrane review assessed the overall evidence for desipramine in neuropathic pain as very low quality under GRADE criteria, citing limited trials, small sample sizes, and high risk of bias, with uncertain benefits outweighing harms.[32] Investigational uses include cocaine dependence, where Phase II-era trials in the 1990s and 2000s evaluated desipramine for promoting abstinence and reducing cravings, often with mixed outcomes. A 1991 meta-analysis of six placebo-controlled trials (n=200) indicated desipramine facilitated initial cocaine abstinence in outpatient settings, though long-term efficacy was inconsistent due to high dropout rates.[33] A 2005 RCT in cocaine-dependent patients with comorbid depression reported mood improvements correlated with reduced cocaine use, supporting its potential in dual-diagnosis cases.[34] Desipramine has also been investigated at low doses for functional dyspepsia and related functional bowel disorders, aiming to alleviate visceral pain through neuromodulation. A 2005 RCT found low-dose desipramine superior to placebo in reducing postprandial symptoms in functional bowel disease patients, though per-protocol analysis showed borderline significance.[35] Broader evidence from TCA class meta-analyses in the 2010s supports low-dose tricyclics for functional gastrointestinal pain, with desipramine occasionally referenced in guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome.[36] Overall, evidence for these off-label and investigational uses is low to moderate quality, with GRADE ratings often very low for pain applications due to methodological limitations and sparse data. Recent 2020s reviews highlight desipramine's potential in ADHD augmentation with stimulants in refractory cases, though dedicated RCTs remain limited. Ongoing research focuses on combination therapies, but no large-scale trials for treatment-resistant depression involving desipramine were identified post-2020.Administration and Dosage

Dosing Guidelines

Desipramine dosing for major depressive disorder typically begins at 25–50 mg orally once daily or in divided doses, with gradual titration by 25–50 mg increments weekly based on clinical response and tolerability, aiming for a maintenance dose of 100–200 mg per day; the maximum recommended dose is 300 mg per day, generally reserved for hospitalized patients under close supervision.[37][38] In special populations, dosing requires reduction to minimize risks. For elderly patients, initiate at 10–25 mg once daily at bedtime, titrating cautiously to a maximum of 100–150 mg per day due to increased sensitivity to anticholinergic and cardiovascular effects.[37][38] In hepatic impairment, use lower starting doses and slower titration, as desipramine undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism, potentially leading to accumulation.[38] Desipramine is not FDA-approved for patients under 18 years due to suicidality risks; off-label pediatric use requires specialist oversight.[1] CYP2D6 poor metabolizers may require dose reductions of 50% or more, with plasma level monitoring to avoid toxicity, as they exhibit 2–10-fold higher concentrations compared to normal metabolizers.[37][39] Monitoring is essential for safe use, per FDA labeling and VA/DoD guidelines updated in 2022. Obtain baseline ECG and monitor periodically for QT prolongation, particularly at doses over 100 mg per day or in patients with cardiac risk factors, as desipramine can cause interval changes.[37][38] Therapeutic plasma levels, while not definitively established by FDA, are commonly targeted at 50–300 ng/mL to guide dosing and assess compliance or toxicity.[1] Initial weekly clinical assessments for suicidality are required in younger patients, with prescriptions limited to small quantities to mitigate overdose risk; in polypharmacy scenarios, especially with CYP2D6 inhibitors like SSRIs, enhanced monitoring for interactions and adverse effects is advised, reflecting 2025 emphases on high-risk medication combinations in older adults.[37][4][40]Pharmacological Forms

Desipramine is formulated exclusively as oral tablets of the hydrochloride salt, which provides enhanced stability and solubility for pharmaceutical use. Available strengths include 10 mg, 25 mg, 50 mg, 75 mg, 100 mg, and 150 mg tablets, allowing for flexible dosing adjustments based on patient needs.[41][42] No intravenous, topical, or other non-oral formulations exist, limiting administration to the oral route. To reduce the risk of gastrointestinal upset, tablets should be taken with food, and despite the drug's variable plasma half-life of 7 to over 60 hours, once-daily dosing—often at bedtime—is feasible for maintenance therapy.[20][43][7] The brand-name product Norpramin is available only in tablet form, while generic desipramine hydrochloride has been widely accessible since the patent expiration in the late 20th century. As of 2025, generic desipramine tablets have been discontinued by several manufacturers, resulting in limited availability; the brand Norpramin remains accessible in some markets.[44][45]Safety Profile

Adverse Effects

Desipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), is associated with various adverse effects attributable to its anticholinergic and noradrenergic mechanisms. Common anticholinergic effects include dry mouth and constipation. Noradrenergic effects often present as insomnia and orthostatic hypotension, which can contribute to dizziness and falls. These effects are generally dose-dependent and more prominent during initial treatment phases.[1] Serious adverse effects, though less frequent, warrant careful monitoring. Cardiac arrhythmias, such as tachycardia and QT prolongation, pose significant risks, particularly in patients with preexisting cardiovascular conditions. In the early 1990s, reports linked desipramine to rare sudden cardiac deaths in a small number of children treated for behavioral disorders like ADHD, even at normal doses, leading to FDA warnings and reduced use in pediatrics.[5][27] Seizures represent a key concern due to a lowered seizure threshold. Weight gain is possible but typically less substantial compared to other TCAs like amitriptyline or imipramine. An increased risk of suicidality has been observed in children, adolescents, and young adults, necessitating close monitoring. Post-marketing surveillance data from the FDA highlight these risks, with overall adverse reaction rates derived from voluntary reports and clinical trials.[5] Risk factors for adverse effects include advanced age, where elderly patients exhibit higher overall incidence (up to 39% for major reactions versus 7% in younger adults), partly due to increased susceptibility to orthostatic hypotension and falls from impaired renal clearance and altered pharmacokinetics. Concomitant use of antipsychotics can elevate rates to 32%. Guidelines recommend ECG monitoring in TCA users to detect QT prolongation and arrhythmias early.[46][47] Management of adverse effects primarily involves dose reduction or discontinuation, with symptomatic relief for milder symptoms like dry mouth through hydration or sialogogues. Desipramine's relatively lower sedating profile compared to amitriptyline may reduce somnolence-related issues, though individual variability persists. Certain drug interactions can amplify these effects, such as those with QT-prolonging agents.[1]Drug Interactions and Contraindications

Desipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant, undergoes significant interactions with cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) inhibitors, such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and quinidine, which can elevate desipramine plasma concentrations by 2- to 10-fold, particularly in poor metabolizers, increasing the risk of toxicity including cardiac arrhythmias and seizures.[48] Concomitant use with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), including linezolid and methylene blue, is contraindicated due to the potential for life-threatening serotonin syndrome; a washout period of at least 14 days is required before initiating desipramine after MAOI discontinuation, and vice versa.[48][41] Drugs that prolong the QT interval, such as certain antipsychotics (e.g., thioridazine) and antiarrhythmics (e.g., quinidine), can amplify desipramine's cardiotoxic effects, leading to enhanced risk of torsades de pointes; electrocardiographic monitoring is recommended in such cases.[48][20] Alcohol consumption exacerbates desipramine's central nervous system depressant effects, intensifying sedation and impairing psychomotor performance, which heightens the danger in overdose scenarios.[48] Case reports have documented fatalities associated with these interactions, including serotonin syndrome from MAOI combinations and severe toxicity from CYP2D6 inhibition leading to elevated levels and multi-organ failure.[49][1] Absolute contraindications to desipramine include the acute recovery phase following myocardial infarction, hypersensitivity to desipramine or other dibenzazepines, and concurrent or recent (within 14 days) MAOI use.[48][50] Relative contraindications encompass narrow-angle glaucoma, due to anticholinergic-induced intraocular pressure elevation, and bipolar disorder, where desipramine may precipitate manic episodes.[20][51] In pregnancy, desipramine is not assigned a formal FDA category but should be used only if the potential benefit justifies the risk, as human data are limited and animal studies inconclusive; neonatal withdrawal symptoms have been reported in exposed infants.[52][53] For elderly patients, the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria strongly recommend avoiding desipramine due to its strong anticholinergic properties, which increase risks of falls, confusion, and delirium, especially in polypharmacy contexts.[54]Overdose and Toxicity

Clinical Presentation

Desipramine overdose manifests through a triad of anticholinergic, cardiovascular, and central nervous system (CNS) effects, often progressing rapidly within hours of ingestion. Anticholinergic symptoms include delirium, hyperthermia, blurred vision, mydriasis, dry mouth, and urinary retention, resulting from muscarinic receptor blockade.[55] Cardiovascular manifestations are prominent and life-threatening, featuring tachycardia, hypotension, arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, and conduction abnormalities like prolonged PR and QT intervals.[56] CNS effects range from agitation and myoclonus to severe seizures, coma, and respiratory depression, contributing to high morbidity.[57] The pathophysiology centers on desipramine's potent blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels in myocardial and neuronal tissues, leading to slowed conduction and membrane stabilization failure. This manifests electrocardiographically as QRS complex widening (>100 ms predictive of seizures, >160 ms of ventricular arrhythmias), right axis deviation in lead aVR, and a sine-wave pattern in severe cases.[58] Case series from the 1970s through the 2020s, including pediatric and adult overdoses, consistently document these ECG changes as harbingers of toxicity, with desipramine exhibiting higher cardiotoxicity than other tricyclic antidepressants due to its noradrenergic selectivity.[59] Recent 2024 toxicology updates reaffirm that QRS prolongation remains a key prognostic indicator, though its incidence has declined with reduced prescribing of tricyclics.[60] A dose exceeding 10 mg/kg is often associated with severe toxicity and fatality in desipramine overdose, with the lowest reported lethal dose around 15 mg/kg across tricyclic antidepressants; desipramine specifically shows severe effects at doses as low as 6 mg/kg in children.[57] Mortality rates from tricyclic antidepressant overdoses, including desipramine, are approximately 1-2% among cases reaching medical facilities with prompt treatment, though desipramine carries a disproportionately higher case fatality rate (up to 2-3 times that of amitriptyline or nortriptyline based on poison control data).[61][62] Risk factors for desipramine overdose include intentional self-poisoning in patients with depression, given its primary use as an antidepressant, and accidental ingestions in pediatrics, where even small amounts (e.g., 5-10 mg/kg) can prove fatal due to the drug's narrow therapeutic index.[63] Therapeutic doses may occasionally mimic mild overdose symptoms like dry mouth or tachycardia, but these are far less severe than in supratherapeutic exposures.[56]Management Strategies

Management of desipramine overdose, a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), follows evidence-based protocols emphasizing rapid stabilization, decontamination, and targeted interventions to address cardiotoxicity, the primary cause of morbidity and mortality. Initial response prioritizes the ABCs—airway management with possible intubation for coma or respiratory depression, breathing support via oxygenation or ventilation, and circulation assessment with intravenous access for fluid resuscitation.[56] Decontamination involves administration of activated charcoal (1 g/kg orally) if ingestion occurred within 2 hours and the airway is protected, as it binds TCAs in the gastrointestinal tract and reduces absorption, though its efficacy diminishes beyond this window.[56] For cardiotoxicity, the cornerstone intervention is intravenous sodium bicarbonate, indicated when QRS duration exceeds 100 ms on ECG, hypotension persists, or ventricular arrhythmias occur. Dosing typically starts with a bolus of 1–2 mEq/kg, followed by an infusion (e.g., 150 mEq in 1 L of D5W at 1.5–2 times maintenance rate) to achieve serum pH 7.45–7.55, which enhances sodium channel unbinding and stabilizes membranes.[56][64] In refractory cases, intravenous lipid emulsion (20% solution, 1.5 mL/kg bolus then 0.25 mL/kg/min infusion) may be used for persistent hemodynamic instability, based on case reports showing improved cardiac function in lipophilic TCA overdoses like desipramine.[56][65] For life-threatening refractory shock or arrest, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) provides circulatory support, as recommended in 2023 American Heart Association guidelines for sodium channel blocker toxicities.[64] Ongoing monitoring includes continuous ECG to track QRS widening and arrhythmias (QRS >160 ms predicts high arrhythmia risk), serial serum TCA levels (though not directly correlative with toxicity severity), and vital signs.[56] Seizures, common in TCA overdose, are managed supportively with benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam 0.05–0.1 mg/kg IV) as first-line therapy, escalating to phenobarbital or propofol if refractory.[56] Hypertonic saline serves as an alternative to bicarbonate for alkalization in patients with contraindications like hypernatremia, targeting similar pH goals while providing sodium loading.[66] Evidence from the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) National Poison Data System indicates improved outcomes with early intervention; for instance, in 2004 data, among over 9,300 treated TCA exposures, only 85 fatalities occurred, yielding survival rates exceeding 99% for managed cases, though many were mild.[57] Recent poison control updates, including 2023 AAPCC reports and toxicology texts, reinforce these protocols, noting decreased mortality (now <5–10%) due to timely bicarbonate and supportive care, with desipramine-specific thresholds for referral at ingestions >2.5 mg/kg.[57][56] Long-term care involves psychiatric evaluation for intentional overdose and monitoring for delayed complications like aspiration pneumonia.[67]Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Desipramine primarily acts as a potent inhibitor of the norepinephrine transporter (NET), preventing the reuptake of norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons with a high affinity (Ki = 0.83 nM at human cloned receptors). It exhibits weaker inhibition of the serotonin transporter (SERT), with a Ki of 25 nM, resulting in a selectivity ratio favoring NET by approximately 30-fold. Desipramine also displays secondary pharmacological effects, including blockade of alpha-1 adrenergic receptors (Ki = 100 nM) and mild antagonism at histamine H1 receptors (Ki ≈ 110 nM). It lacks significant affinity for the dopamine transporter (DAT), with Ki values exceeding 10,000 nM, thereby exerting minimal direct influence on dopaminergic neurotransmission.[11] By blocking NET, desipramine elevates extracellular norepinephrine levels in key brain regions such as the locus coeruleus and prefrontal cortex, enhancing stimulation of postsynaptic beta-adrenergic receptors. This increased noradrenergic signaling contributes to therapeutic effects like mood stabilization and alleviation of depressive symptoms through downstream activation of cyclic AMP pathways and gene expression changes in neuronal plasticity. With chronic administration, desipramine induces downregulation of beta-adrenergic receptors, which may underlie adaptive responses and long-term efficacy in treating mood disorders.[68] Compared to its parent compound imipramine, which shows balanced but less selective inhibition (Ki = 20 nM for NET and 1.3 nM for SERT), desipramine demonstrates greater noradrenergic specificity. The extent of transporter inhibition can be quantified using the fractional occupancy model: where represents the free drug concentration and is the inhibition constant; at therapeutic plasma levels (typically 100–300 ng/mL, approximately 375–1125 nM), desipramine achieves near-complete NET occupancy while only partially occupying SERT. Recent neuroimaging studies, including positron emission tomography (PET) assessments of NET binding in patients with major depressive disorder, have confirmed that NET inhibitors like desipramine reduce transporter availability in noradrenergic pathways, correlating with symptomatic improvement after prolonged treatment.[11][69]Pharmacokinetics

Desipramine exhibits moderate oral bioavailability of approximately 40-70%, reflecting variability due to extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism following gastrointestinal absorption. Peak plasma concentrations (T_max) are typically reached 4-6 hours after oral dosing.[3][70][4] The drug is widely distributed throughout the body, with a volume of distribution (V_d) ranging from 10-50 L/kg, attributed to its high lipophilicity and tissue binding. Protein binding to plasma proteins is 73-92%, and desipramine readily crosses the blood-brain barrier, facilitating its central nervous system effects.[3][70][71] Metabolism occurs primarily in the liver via the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2D6, forming the active metabolite 2-hydroxydesipramine through 2-hydroxylation. Minor pathways involve CYP1A2-mediated 10-hydroxylation and N-demethylation. The elimination half-life of desipramine averages 12-30 hours but can extend significantly (up to 60 hours or more) in individuals with reduced CYP2D6 activity.[3][70][72] Excretion is predominantly renal, with approximately 70% of the dose recovered in urine, primarily as metabolites; less than 5% is eliminated unchanged. Total clearance varies widely, typically 40-110 L/h, influenced by metabolic capacity.[3][70][72] Pharmacokinetic variability is largely driven by genetic polymorphisms in CYP2D6, with 5-10% of Caucasians classified as poor metabolizers (PMs) exhibiting reduced clearance and prolonged half-life, leading to higher plasma concentrations. Intermediate metabolizers (IMs) show moderate reductions in clearance, while ultrarapid metabolizers (UMs) may require higher doses for efficacy. According to CPIC guidelines for tricyclic antidepressants, dosing adjustments are recommended: standard dosing for normal metabolizers, 25% dose reduction for IMs, 50% reduction for PMs with therapeutic drug monitoring, and consideration of alternatives or higher doses with monitoring for UMs. Steady-state plasma concentrations (C_ss) can be estimated using the formula: where CL is clearance and \tau is the dosing interval; this is particularly useful in pharmacogenomically guided dosing to avoid toxicity in PMs.[70][72][73]Chemistry

Chemical Structure and Properties

Desipramine, chemically known as 3-(10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenz[b,f]azepin-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine, is a tricyclic dibenzazepine derivative with the molecular formula C18H22N2 and a molecular weight of 266.38 g/mol.[7] Its IUPAC name is 3-(5,6-dihydrobenzo[74]benzazepin-11-yl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine, and the SMILES notation is CNCCCN1C2=CC=CC=C2CCC3=CC=CC=C31.[7] The core structure consists of a seven-membered azepine ring fused to two benzene rings, with a propylamine side chain at the nitrogen position bearing a methyl group.[3] In its hydrochloride salt form, desipramine appears as a white to off-white crystalline powder.[75] It exhibits basic properties with a pKa of approximately 10.15 for the aliphatic amine group.[7] The free base has limited solubility in water (about 58.6 mg/L at 24°C), but the hydrochloride salt is more soluble, dissolving at a rate of 1 g in 20 mL of water, and is also freely soluble in alcohol and chloroform while being insoluble in ether.[7] Desipramine hydrochloride is sensitive to prolonged exposure to light, heat, and air, which can lead to degradation.[7] It should be stored at room temperature in a tightly closed container to maintain stability.[75] As the primary active demethylated metabolite of imipramine, desipramine retains the characteristic tricyclic ring system of its parent compound while exhibiting enhanced selectivity for norepinephrine reuptake inhibition.[3]Synthesis and Metabolism

Desipramine is synthesized through a multi-step process starting from iminodibenzyl (10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenz[b,f]azepine), involving alkylation with 1-bromo-3-chloropropane in the presence of sodium amide to form 5-(3-chloropropyl)-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenz[b,f]azepine, followed by reaction with methylamine to yield desipramine.[76] This route, which includes key steps of alkylation and amine substitution, was patented in 1962 by Geigy as British Patent 908,788 for the free base and hydrochloride forms.[7] Alternative synthetic approaches include direct N-demethylation of imipramine or reduction of imipramine N-oxide, though isotope-trapping studies indicate that imipramine N-oxide is not an obligatory intermediate in desmethylation pathways.[77] Overall yields for normethyl precursor synthesis from iminodibenzyl typically reach 35%.[78] Purity of desipramine is routinely assessed using reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) methods, which enable quantification with high sensitivity and specificity, often achieving detection limits suitable for pharmaceutical-grade analysis exceeding 98% purity.[79][80] In vivo, desipramine is primarily metabolized in the liver via aromatic hydroxylation to the active metabolite 2-hydroxydesipramine, mediated mainly by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2D6, with minor contributions from CYP1A2.[3] This hydroxylation pathway exhibits genetic variability influenced by CYP2D6 polymorphisms, leading to differences in metabolite formation and drug clearance.[81] Further transformations include glucuronidation of hydroxy metabolites for excretion, though N-demethylation to primary amines occurs to a lesser extent compared to hydroxylation.[82] No significant environmental concerns have been noted in standard synthesis processes for desipramine.History and Development

Discovery and Early Research

Desipramine, also known as desmethylimipramine or G-35020, was first identified in 1959 by chemists at the pharmaceutical company J.R. Geigy in Basel, Switzerland, as the principal active metabolite of imipramine, the first tricyclic antidepressant.[83] This discovery stemmed from metabolic studies on imipramine, revealing desipramine's independent pharmacological potential, leading to its separate synthesis with a Swiss patent priority date of September 4, 1959.[83] Early isolation efforts focused on its structural similarity to imipramine but with a secondary amine configuration, prompting targeted evaluation for antidepressant activity beyond its role as a metabolite.[84] Preclinical research in the late 1950s and early 1960s, building on imipramine's established effects, utilized animal models to explore desipramine's mechanism, particularly its influence on norepinephrine. Studies in rats demonstrated that desipramine rapidly reversed reserpine-induced sedation and ptosis—behavioral indicators of monoamine depletion—more potently than imipramine, suggesting enhanced noradrenergic activity through selective inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake at peripheral sympathetic nerves.[84] Key experiments by Carlsson et al. (1961), Dengler et al. (1961), and Axelrod et al. (1961) confirmed this selectivity in vivo, showing desipramine's preferential blockade of norepinephrine uptake over serotonin, unlike the broader profile of imipramine.[84] However, overdose models in rodents raised early concerns about cardiotoxicity, with high doses inducing arrhythmias and convulsions similar to imipramine, attributed to sodium channel blockade and heightened noradrenergic stimulation.[57] The first human trials commenced in 1962, with preliminary investigations evaluating desipramine's safety and efficacy in small cohorts of depressed patients, often comparing it directly to imipramine in Phase I studies.[85] These open-label assessments, such as those by Azima et al. and Ban and Lehmann, reported rapid onset of antidepressant effects at doses of 75–150 mg daily, with improvements in psychomotor retardation and anhedonia noted within one week, supporting its noradrenergic selectivity observed in animals.[84] A landmark 1963 publication in Psychopharmacologia detailed a controlled comparison in normal subjects and depressive patients, confirming desipramine's efficacy comparable to imipramine but with fewer anticholinergic side effects and a profile favoring noradrenergic symptoms.[86] By 1964, cumulative 1960s trial data from over 100 patients underscored this selectivity, with desipramine showing superior response in vital depressions characterized by low energy, though initial reports highlighted risks of orthostatic hypotension and tachycardia in sensitive individuals.[84]Regulatory Milestones

Desipramine was first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on December 18, 1964, under the brand name Pertofrane for the treatment of depression.[87] This approval marked it as one of the early tricyclic antidepressants available in the United States, following closely after imipramine in 1959.[88] Generic versions of desipramine hydrochloride entered the U.S. market in the late 1980s, with the FDA granting approval to Actavis Totowa on June 5, 1987, for oral tablets in various strengths.[44] Additional generic approvals followed, reflecting the expiration of original patents and increased competition, which improved accessibility for patients.[89] In the early 1990s, reports of rare sudden cardiac deaths in a small number of children treated with desipramine at therapeutic doses, primarily for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), prompted FDA responses including label updates advising caution for pediatric use. These reports, first documented in 1990 with three cases and followed by additional incidents, led to heightened scrutiny and a significant reduction in its prescription for children.[27][5] Internationally, desipramine received marketing authorization in Europe shortly after its U.S. debut, with initial approvals in the mid-1960s, including by regulatory bodies equivalent to the modern European Medicines Agency (EMA).[2] However, in some countries such as the United Kingdom, its use has diminished since the 2000s due to the availability of safer antidepressant alternatives with fewer cardiac risks.[90] Post-marketing surveillance led to significant label updates. In 2004, the FDA issued a black box warning for all antidepressants, including desipramine, highlighting an increased risk of suicidality in pediatric patients.[91] This warning was expanded in May 2007 to include young adults aged 18 to 24 years, based on analyses showing elevated risks during initial treatment phases.[5] In the 2010s, product labels were revised to emphasize cardiac monitoring, recommending ECG assessments and vital sign checks due to potential effects on heart rate and conduction, particularly in patients with preexisting cardiovascular conditions.[92] As of 2025, the FDA continues to restrict pediatric use of desipramine, with labels explicitly stating it is not approved for patients under 18 due to insufficient evidence of efficacy and heightened suicidality risks, reinforcing longstanding post-approval precautions.[93]Society and Culture

Generic and Brand Names

Desipramine is the international nonproprietary name (INN) assigned by the World Health Organization for this tricyclic antidepressant.[94] The United States Adopted Name (USAN) is desipramine hydrochloride, referring to the commonly used salt form of the drug.[5] In the United States, desipramine is primarily available under the brand name Norpramin, marketed by Validus Pharmaceuticals LLC since its FDA approval.[93] Internationally, it has been sold under various brand names, including Pertofrane (originally by Ciba-Geigy and later USV), which was widely used in Europe but has been discontinued in several markets.[3] Desipramine was first introduced commercially by Geigy Pharmaceuticals in 1964 under early branding associated with Pertofrane.[95] Linguistic variations of the generic name appear in non-English markets, such as desipramina in Spanish-speaking regions like Spain and Latin America. In French-speaking countries, it is denoted as désipramine. In recent years, generic versions of desipramine hydrochloride have become available in emerging markets, including India, where it is distributed through pharmaceutical exporters without prominent proprietary branding.[96]Availability and Legal Status

In the United States, desipramine is classified as a prescription-only medication (Rx-only) and is not a controlled substance under the DEA schedules, making it widely available in generic form from multiple manufacturers.[20][44] Internationally, desipramine remains available by prescription in Canada, where it is approved and marketed by companies such as Apotex Inc. and AA Pharma Inc., though tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) like desipramine face restrictions in some contexts due to safety concerns including cardiac risks and overdose potential.[97][98] In the European Union, desipramine is authorized for specific uses but with limitations on TCA prescriptions, often requiring specialist oversight and black-box warnings for suicidality and cardiovascular effects; its orphan drug designation for conditions like Rett syndrome was withdrawn in 2017.[99][100][101] In contrast, desipramine was withdrawn from the Australian market in the early 2000s following manufacturer discontinuation due to low profitability and shifts toward newer antidepressants, rendering it unavailable despite efforts by psychiatric organizations to retain it.[90] Desipramine has experienced periodic supply shortages in the US, including ongoing issues reported from 2022 through 2024 and into 2025, primarily affecting generic tablet formulations due to manufacturing delays and market discontinuations by some suppliers; as of August 2025, Avet Pharmaceuticals discontinued all strengths, followed by a recall of nine lots in October 2025, though generics remain available from other manufacturers such as Alembic and Teva.[45][102][103] The generic form of desipramine is inexpensive, typically costing $10–20 per month for a standard 30-tablet supply at common dosages, and it is not available over-the-counter anywhere. Desipramine is not included on the 2025 WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, though alternative TCAs such as amitriptyline and imipramine are listed for depressive disorders.[104][105][106]References

- Desipramine is a secondary amine tricyclic antidepressant that is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression. This drug has off-label use to treat bulimia ...