Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Miles per gallon gasoline equivalent

View on Wikipedia

Miles per gallon gasoline equivalent (MPGe or MPGge) is a measure of the average distance traveled per unit of energy consumed. MPGe is used by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to compare energy consumption of alternative fuel vehicles, plug-in electric vehicles and other advanced technology vehicles with the energy consumption[1] of conventional internal combustion vehicles rated in miles per U.S. gallon.[2][3]

The unit of energy consumed is deemed to be 33.7 kilowatt-hours without regard to the efficiency of conversion of heat energy into electrical energy, also measured in kilowatt-hours (kWh). The equivalence of this unit to energy in a gallon of gasoline is true if and only if the heat engine, generating equipment, and power delivery to the car battery are 100% efficient. Actual heat engines differ vastly from this assumption.

MPGe does not necessarily represent an equivalency in the operating costs between alternative fuel vehicles and the MPG rating of internal combustion engine vehicles due to the wide variation in costs for the fuel sources regionally[4][5] since the EPA assumes prices that represents the national averages.[6][7] Miles per gallon equivalent cost for alternate fuel can be calculated with a simple conversion to the conventional mpg (miles per gallon, miles/gal). See conversion to MPG by cost below.

The MPGe metric was introduced in November 2010 by EPA in the Monroney sticker of the Nissan Leaf electric car and the Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid. The ratings are based on EPA's formula, in which 33.7 kWh (121 MJ) of electricity is equivalent to one (U.S.) gallon of gasoline,[8] and the energy consumption of each vehicle during EPA's five standard drive cycle tests simulating varying driving conditions.[9][10] All new cars and light-duty trucks sold in the U.S. are required to have this label showing the EPA's estimate of fuel economy of the vehicle.[3]

In a joint ruling issued in May 2011 the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and EPA established the new requirements for a fuel economy and environment label that is mandatory for all new passenger cars and trucks starting with model year 2013. This ruling uses miles per gallon gasoline equivalent for all fuel and advanced technology vehicles available in the U.S. market including plug-in hybrids, electric vehicles, flexible-fuel vehicles, hydrogen fuel cell vehicle, natural gas vehicles, diesel-powered vehicles, and gasoline-powered vehicles.[11][12] In addition to being displayed on new vehicles, fuel economy ratings are used by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to publish the annual Fuel Economy Guide; the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) to administer the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) program; and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to collect gas guzzler taxes.[3]

Fuel economy estimates for window stickers and CAFE standard compliance are different. The EPA MPGe rating shown in the Monroney label is based on the consumption of the on-board energy content stored in the fuel tank or in the vehicle's battery, or any other energy source, and only represents the tank-to-wheel energy consumption. CAFE estimates are based on a well-to-wheel basis and in the case of liquid fuels and electric drive vehicles also account for the energy consumed upstream to produce the fuel or electricity and deliver it to the vehicle. Fuel economy for CAFE purposes include an incentive adjustment for alternative fuel vehicles and plug-in electric vehicles which results in higher MPGe than those estimated for window stickers.[13][14]

Background

[edit]1988: Alternative Motor Fuels Act

[edit]The Alternative Motor Fuels Act (AMFA) enacted in 1988[15] provides Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) incentives for manufacturing alternative fuel vehicles (AFVs) that are powered by ethanol, methanol, or natural gas fuels, either exclusively or in conjunction with gasoline or diesel fuel. These dual-fuel vehicles also are known as flexible-fuel vehicles (FFVs). To provide incentives for the widespread use of these fuels and to promote the production of AFVs and FFVs, AMFA grants AFV/FFV manufacturers CAFE credits, which allows them to raise their overall fleet fuel economy levels to comply with the CAFE standards.[16][17]

Beginning in 1993, manufacturers of qualified AFVs can improve their CAFE estimation by computing the weighted average of the fuel economy when operating on conventional fuel (gasoline and diesel) and when operating on alternative fuel(s).[16]: 9–10 AMFA provides the following energy content-based equivalency factors:[15]: §513

- 1 gal (alcohol) = 0.15 gal (gasoline)

- 100 ft3 (natural gas) = 0.823 gal-equivalent (natural gas)

- 1 gal-equivalent (natural gas) = 0.15 gal (gasoline)

A dedicated AFV which operates solely on alcohol would divide the alcohol fuel economy by the energy-equivalency factor of 0.15. As an example, a dedicated AFV that achieves 15 mpg fuel economy while operating on alcohol would have a CAFE calculated as follows:[16]: 10

For FFVs, an assumption is made that the vehicles would operate 50% of the time on the alternative fuel and 50% of the time on conventional fuel, resulting in a fuel economy that is based on a harmonic average of alternative fuel and conventional fuel. For example, for an alternative dual-fuel model that achieves 15 miles per gallon operating on an alcohol fuel and 25 mpg on the conventional fuel, the resulting CAFE would be:[16]: 10

Calculation of fuel economy for natural gas vehicles is similar. For the purposes of this calculation, the fuel economy is equal to the weighted average of the fuel economy while operating on natural gas and while operating on either gasoline or diesel fuel. AMFA specifies the energy content of 100 cubic feet of natural gas to be equal to 0.823 gallons-equivalent of natural gas, and the gallon equivalency of natural gas is considered to have a fuel content, similar to that for alcohol fuels, equal to 0.15 gallons of fuel. For example, under this conversion and gallon equivalency, a dedicated natural gas vehicle that achieves 25 miles per 100 cubic feet of natural gas would have a CAFE value as follows:[16]: 10

The Energy Policy Act of 1992 expanded the definition of alternative fuel to include liquefied petroleum gas, hydrogen, liquid fuels derived from coal and biological materials, electricity and any other fuel that the Secretary of Transportation determines to be substantially non-petroleum based and has environmental and energy security benefits. Beginning in 1993, manufacturers of these other alternative fuel automobiles that meet the qualifying requirements can also benefit for special treatment in the calculation of their CAFE.[17]

1994: Gasoline gallon equivalent

[edit]In 1994 the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) introduced gasoline gallon equivalent (GGE) as a metric for fuel economy for natural gas vehicles. NIST defined a gasoline gallon equivalent (GGE) as 5.660 pounds of natural gas, and gasoline liter equivalent (GLE) as 0.678 kilograms of natural gas.[18]

2000: Petroleum-equivalent fuel economy

[edit]| Vehicle | Model year | Type of battery | Energy use (kWh/mile) | Energy efficiency (miles/kWh) | Energy efficiency (MPGe, miles/33.7 kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM EV1[19] | 1997 | Lead acid | 0.164 | 6.10 | 205[note 1] |

| GM EV1[20] | 1999 | NiMH | 0.179 | 5.59 | 188[note 1] |

| Toyota RAV4 EV[21] | 1996 | Lead acid | 0.235 | 4.28 | 143 |

| Toyota RAV4 EV[22] | 2000 | NiMH | 0.400 | 2.50 | 84 |

| Ford Ranger EV[23] | 1998 | Lead acid | 0.337 | 2.98 | 100 |

| Chevrolet S-10 EV[24] | 1997 | Lead acid | 0.292 | 3.42 | 115 |

During the late 1990s and early 2000s several electric cars were produced in limited quantities as a result of the California Air Resources Board (CARB) mandate for more fuel-efficient zero-emissions vehicles. Popular models available in California included the General Motors EV1 and the Toyota RAV4 EV.[25][26] The U.S. DoE and EPA rating for on board energy efficiency for these electric vehicles was expressed as kilowatt hour/mile (KWh/mi), the most commonly known metric in science and engineering for measuring energy consumption, and used as the billing unit for energy delivered to consumers by electric utilities.[27]

In order to address the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) regulations mandated by the U.S. Congress in 1975, the U.S. Department of Energy established in July 2000 a methodology for calculating the petroleum-equivalent fuel economy of electric vehicles on a well-to-wheel basis. The methodology considers the upstream efficiency of the processes involved in the two fuel cycles. The energy content of gasoline is reduced from 33,705 Wh/gal to 83% of that, or about 27,975 Wh/gal well-to-tank, to account for the energy used in refinement and distribution. Similarly, the energy value for electricity produced from fossil fuel is reduced to 30.3% due to energy lost in generation and transmission, according to the national average. This is normalized to the previous gasoline value, resulting in a well-to-vehicle gasoline-equivalent energy content of electricity of only 12,307 Wh/gal.[14]

The formula also includes a "fuel content factor" of 1/0.15 (about 6.667) to benefit electric vehicles, raising the value from 12,307 to 82,049 Wh/gal. This reward factor is intended provide an incentive for vehicle manufactures to produce and sell electric vehicles, as a higher equivalent fuel economy for EVs improves the carmaker overall fleet fuel economy levels in complying with the CAFE standards, and Congress anticipated that such an incentive would help accelerate the commercialization of electric vehicles. The incentive factor chosen by DoE for EVs is the same 1/0.15 factor already applied in the regulatory treatment of other types of alternative fuel vehicles.[14] When all factors are considered in DoE's formula, the energy efficiency or equivalent fuel economy of electric vehicles increases, being calculated in miles per the petroleum-equivalency factor of 82,049 Wh/gal rather than miles per the usual gasoline gallon equivalent of 33,705 Wh/gallon, for the purposes of CAFE credits to manufacturers.[27]

2007: X Prize

[edit]The Automotive X Prize competition was intended to encourage development of automobiles that would be capable of operating 100 miles on a gallon of gasoline (mpg). Comparison of electric vehicles to vehicles that carried their own engine was debated, since the notion of a miles per gallon equivalent as a metric for electric vehicles made the competition trivial for electric vehicles and a corresponding miles per gallon as a metric for the others extremely difficult for the others. Miastrada Company made the case that this defeated the purpose of the competition, to no avail. In April 2007, as part of Draft Competition Guidelines released at the New York Auto Show, MPGe was announced as the main merit metric for the Progressive Insurance Automotive X Prize, a competition developed by the X Prize Foundation for super-efficient vehicles that can achieve at least 100 MPGe.[28] In February 2009, Consumer Reports announced that, as part of a partnership with the X Prize Foundation, they planned to report MPGe as one of several measures that will help consumers understand and compare vehicle efficiency for alternative fuel vehicles.[29]

2010–2011: Miles per gallon equivalent

[edit]As required by the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA), with the introduction of advanced-technology vehicles in the U.S. new information should be incorporated in the Monroney label of new cars and light-duty trucks sold in the country, such as ratings on fuel economy, greenhouse gas emissions, and other air pollutants. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) have conducted a series of studies to determine the best way to redesign this label to provide consumers with simple energy and environmental comparisons across all vehicles types, including battery electric vehicles (BEV), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV), and conventional internal combustion engine vehicles powered by gasoline and diesel, in order to help consumers choose more efficient and environmentally friendly vehicles. These changes were proposed to be introduced in new vehicles beginning with model year 2012.[3][30]

The EPA rating for on board energy efficiency for electric vehicles before 2010 was expressed as kilowatt hour per 100 miles (kWh/100 mi).[27][31] For example, the window sticker of the 2009 Mini E showed an energy consumption of 33 kWh/100 mi for city driving and 36 kWh/100 mi on the highway, technically equivalent to 100 mpg‑e city and 94 mpg‑e highway.[31] Similarly, the 2009 Tesla Roadster was rated 32 kWh/100 mi (110 mpg‑e) in city and 33 kWh/100 mi (100 mpg‑e) on the highway.[32][33]

As part of the research and redesign process, EPA conducted focus groups where participants were presented with several options to express the consumption of electricity for plug-in electric vehicles. The research showed that participants did not understand the concept of a kilowatt hour as a measure of electric energy use despite the use of this unit in their monthly electric bills. Instead, participants favored a miles per gallon equivalent, MPGe, as the metric to compare with the familiar miles per gallon used for gasoline vehicles. The research also concluded that the kWh per 100 miles metric was more confusing to focus group participants compared to a miles per kWh. Based on these results, EPA decided to use the following fuel economy and fuel consumption metrics on the redesigned labels: MPG (city and highway, and combined); MPGe (city and highway, and combined); Gallons per 100 miles; kWh per 100 miles.[30]

The proposed design and final content for two options of the new sticker label that would be introduced in 2013 model year cars and trucks were consulted for 60 days with the public in 2010, and both include miles per gallon equivalent and kWh per 100 miles as the fuel economy metrics for plug-in cars, but in one option MPGe and annual electricity cost are the two most prominent metrics.[34][35] In November 2010, EPA introduced MPGe as comparison metric on its new sticker for fuel economy for the Nissan Leaf and the Chevrolet Volt.[9][10]

In May 2011, the NHTSA and EPA issued a joint final rule establishing new requirements for a fuel economy and environment label that is mandatory for all new passenger cars and trucks starting with model year 2013. The ruling includes new labels for alternative fuel and alternative propulsion vehicles available in the US market, such as plug-in hybrids, electric vehicles, flexible-fuel vehicles, hydrogen fuel cell vehicle, and natural gas vehicles.[11][12] The common fuel economy metric adopted to allow the comparison of alternative fuel and advanced technology vehicles with conventional internal combustion engine vehicles is miles per gallon of gasoline equivalent (MPGe). A gallon of gasoline equivalent means the number of kilowatt hours of electricity, cubic feet of compressed natural gas (CNG), or kilograms of hydrogen that is equal to the energy in a gallon of gasoline.[11]

The new labels also show for the first time an estimate of how much fuel or electricity it takes to drive 100 miles (160 km), introducing to U.S. consumers with fuel consumption per distance traveled, a metric commonly used in other countries. EPA explained that the objective is to avoid the traditional miles per gallon metric that can be potentially misleading when consumers compare fuel economy improvements, and known as the "MPG illusion".[11]

As mentioned above, confusion and misinterpretation is common in the public between the two types of "fuel efficiency". Fuel economy measures how far a vehicle will go per amount of fuel (units of MPGe). Fuel consumption is the reciprocal of fuel economy, and measures the fuel used to drive a fixed distance (units of gal/100 miles or kWh/100 miles).[36] The unit of Gal/100 miles is accurately described as fuel consumption in some EPA brochures, but this unit appears in the fuel economy section of the Monroney label (which does not use the term fuel consumption).[37][38]

Description

[edit]The miles per gallon gasoline equivalent is based on the energy content of gasoline. The energy obtainable from burning one US gallon of gasoline is 115,000 BTU, 33.70 kWh, or 121.3 MJ.[8]

To convert the mile per gallon rating into other units of distance per unit energy used, the mile per gallon value can be multiplied by one of the following factors to obtain other units:

Conversion to MPGe

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

MPGe is determined by converting the vehicle consumption per unit distance, as determined through computer modeling or completion of an actual driving cycle, from its native units into a gasoline energy equivalent. Examples of native units include W·h for electric vehicles, kg-H

2 for hydrogen vehicles, gallons for biodiesel or liquefied natural gas vehicles, cubic feet for compressed natural gas vehicles, and pounds for propane or Liquefied petroleum gas vehicles. Special cases for specific alternative fuels are discussed below, but a general formula for MPGe is:

For EPA, this considers the tank-to-wheel for liquids and wall-to-wheel energy consumption for electricity, i.e. it measures the energy for which the owner usually pays. For EVs the energy cost includes the conversions from AC to charge the battery.[39] The EPA MPGe ratings displayed in window stickers do not account for the energy consumption upstream, which includes the energy or fuel required to generate the electricity or to extract and produce the liquid fuel; the energy losses due to power transmission; or the energy consumed for the transportation of the fuel from the well to the station.[14][40]

Basic values for the energy content of various fuels are given by the defaults used in the Department of Energy GREET (Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy used in Transportation) model,[41] as follows:

Note: 1 kWh is equivalent to 3,412 BTU

| Fuel | Unit | Energy/unit | GGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| gasoline | gallon | 116,090 BTU (34.02 kWh) | 1.0000 |

| diesel | gallon | 129,488 BTU (37.95 kWh) | 0.8965 |

| biodiesel | gallon | 119,550 BTU (35.04 kWh) | 0.9711 |

| ethanol | gallon | 76,330 BTU (22.37 kWh) | 1.5209 |

| E85 | gallon | 82,000 BTU (24.03 kWh) | 1.4157 |

| CNG | 100 SCF | 98,300 BTU (28.81 kWh) | 1.181 |

| H 2 |

KG | 114,000 BTU (33.41 kWh) | 1.0183 |

| LPG | gallon | 84,950 BTU (24.90 kWh) | 1.3666 |

| methanol | gallon | 57,250 BTU (16.78 kWh) | 2.0278 |

The energy content of a particular fuel can vary somewhat given its specific chemistry and production method. For example, in the new efficiency ratings that have been developed by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) – see below – the energy content of a gallon of gasoline is assumed to be 114,989.12 BTU or 33.7 kWh.[8]

Conversion to MPG by cost

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (February 2018) |

The miles per gallon equivalent cost of an alternative fuel vehicle can be calculated by a simple formula to directly compare the MPG operating costs (rather than the energy consumption of MPGe[7]) with traditional vehicles since the cost of resources varies substantially from region to region.[5][4] For reference, the complete equation is:

Also for those that prefer kWh/100 mi an equivalent is simply:

This equation reduces down to a simple formula that works with only the capacity of the fuel source and its possible range to compare vehicles. With your local rates for gasoline and your fuel source you can easily compare your alternative fuel vehicle operating cost directly with a gasoline engine model with the following:

The formula includes the inherent efficiency of the vehicle as the range capability of a specific fuel source capacity directly represents the EPA testing, it then becomes universal regardless of weight, vehicle size, co-efficient of drag, rolling resistance as these directly influence the range possible and are accounted for. Driving style and weather conditions can be accounted for by using the achieved range instead of the advertised range for the calculation.

The formula works by deriving how much alternative fuel can be purchased for the cost of a gallon of gasoline, creating a ratio of this quantity to the storage capacity of the vehicle, and then multiplies this ratio by the vehicle's possible range. The result is number of miles the vehicle travels on alternative fuel for the same cost of a single gallon of gasoline.

The end computation results in MPG unit and is directly comparable to a standard internal combustion engine vehicle's fuel costs for its rated MPG.

Examples

[edit]The formula with the correct units for a BEV or PHEV in all electric mode is like this.

Using EPA 2018 Fuel Economy Guides assumptions for national average pricing of $2.56/gal regular gasoline and $0.13/kWh[42] we can calculate a vehicle that is rated at 84 MPGe or 40 kW/100 Mi efficiency and has a 16.5 kW EV battery of which 13.5 kWh is usable for electric driving with an advertised range of 33 miles per charge.

Note: Using the battery size instead of the usable charge will provide a conservative value. Using actual charge and actual range driven will provide actual economy.

Calculate how many kWh per gallon

Now the same vehicle where gasoline with worth $3.20/gal and electricity is $0.085/kWh.

Calculate how many kWh per gallon

Electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles

[edit]

Between 2008 and 2010 several major automakers began commercializing battery electric vehicles (BEVs), which are powered exclusively on electricity, and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), which use electricity together with a liquid fuel stored in an on-board fuel tank, usually gasoline, but it might be also powered by diesel, ethanol, or flex-fuel engines.

For battery electric vehicles, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's formula to calculate the well-to-wheel MPGe is based on energy standards established by the U.S. Department of Energy in 2000:[2][13][14] The well-to-wheel conversion is used in calculation of corporate-average fuel economy (CAFE) but not for window sticker (Monroney) fuel economy. For Monroney fuel economy the equation is

where

- is expressed as miles per gallon gasoline equivalent (as shown in the Monroney label)

- energy content per gallon of gasoline = 115,000 Btu/gallon, as set by U.S. DoE and reported by the Alternative Fuel Data Center.[14]

- wall-to-wheel electrical energy consumed per mile (Wh/mi) as measured through EPA's five standard drive cycle tests for electric cars and SAE test procedures[13][39]

- energy unit conversion factor (rounded) = 3.412 Btu/Wh[14]

The formula employed by the EPA for calculating their rated MPGe does not account for any fuel or energy consumed upstream such as the generation and transmission of electrical power, or well-to-wheel life cycle, as EPA's comparison with internal combustion vehicles is made on a tank-to-wheel versus battery-to wheel basis.

The California Air Resources Board uses a different dynamometer testing than EPA, and considers reformulated gasoline sold in that state. For CARB estimates the formula becomes:[13]

The new SAE J1711 standard for measuring the exhaust emissions and fuel economy of hybrid electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids was approved in July 2010. The recommended procedures for PHEVs were revised at Argonne National Laboratory, and EPA's new regulation to define PHEV fuel economy reporting protocol is expected to be based on SAE J1711.[43][44] In November 2010 EPA decided to rate electric mode and gasoline only mode separately, and these are the two figures prominently displayed in the window sticker of the 2011 Chevrolet Volt. In electric mode the Volt's rating is estimated with the same formula as an electric car.[10][13] The overall or composite fuel economy rating combining electricity and gasoline powered are displayed in the Monroney label in a much smaller type, and as part of the comparison of the Volt's fuel economy among all vehicles and within compact cars.[45] EPA has considered several methodologies for rating the overall fuel economy of PHEVs, but as of February 2011 EPA has not announced the final methodology that will be applied for the purposes of estimating the new manufacture's 2012–2016 Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) credits for plug-in hybrids.[13][46]

Examples

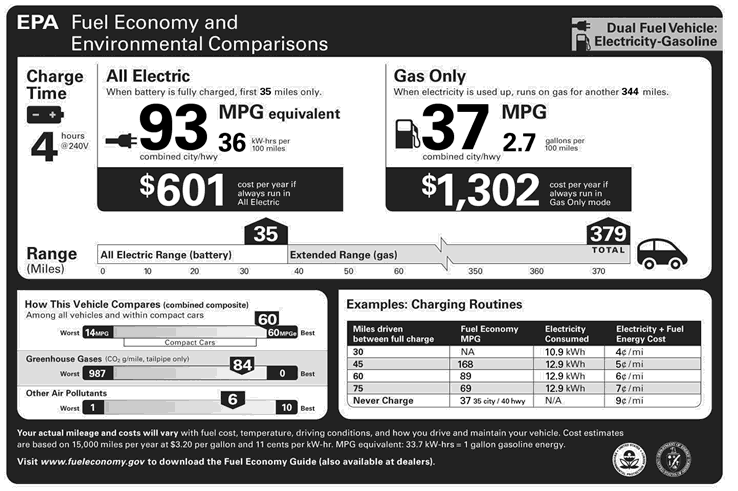

[edit]In November 2010 the EPA began including "MPGe" in its new sticker for fuel economy and environmental comparisons. The EPA rated the Nissan Leaf electric car with a combined fuel economy of 99 MPGe,[9] and rated the Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid with a combined fuel economy of 93 MPGe in all-electric mode, 37 MPG when operating with gasoline only, and an overall fuel economy rating of 60 mpg-US (3.9 L/100 km) combining power from electricity and gasoline.[10][45][47] For both vehicles EPA calculated the MPGe rating under its five-cycle tests using the formula displayed earlier with a conversion factor of 33.7 kWh of electricity being the energy equivalent of a gallon of gasoline.[10]

All-electric cars

[edit]The following table compares official EPA ratings for fuel economy (in miles per gallon gasoline equivalent, mpg-e or MPGe, for plug-in electric vehicles) for series production all-electric passenger vehicles rated by the EPA for model years 2015,[48] 2016,[49] 2017,[50] and 2023[51] versus the model year 2016 vehicles that were rated the most efficient by the EPA with plug-in hybrid drivetrains (Chevrolet Volt – second generation), gasoline-electric hybrid drivetrains (Toyota Prius Eco - fourth generation),[52][53][54] and the average new vehicle for that model year, which has a fuel economy of 25 mpg‑US (9.4 L/100 km; 30 mpg‑imp).[49][52]

EPA rating data are taken from manufacturer testing of their own vehicles using a series of tests specified by federal law. Manufacturers usually conduct the tests using pre-production prototypes. Manufacturers report the results to EPA. The EPA then reviews the results and selects about 15%–20% of them to confirm through their own tests at the National Vehicles and Fuel Emissions Laboratory.[55]

| Comparison of top fuel efficient battery-electric vehicles versus most efficient fossil fuel vehicles (including hybrid-electric vehicles) (Fuel economy as displayed in the Monroney label)[48][49][50] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Model year |

EPA rated fuel economy | Notes | ||||

| Combined | City | Highway | |||||

| Toyota Prius HEV[51] | 2023 | 57 mpg | 57 mpg | 56 mpg | (9) | ||

| Hyundai Ioniq 6 Long Range RWD w/ 18-inch wheels[51] | 2023 | 140 mpg‑e 24.1 kWh/100 mi; 15.0 kWh/100 km |

153 mpg‑e 22.0 kWh/100 mi; 13.7 kWh/100 km |

127 mpg‑e 26.5 kWh/100 mi; 16.5 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Lucid Air Pure AWD w/ 19-inch wheels[51] | 2023 | 140 mpg‑e 24.1 kWh/100 mi; 15.0 kWh/100 km |

141 mpg‑e 23.9 kWh/100 mi; 14.9 kWh/100 km |

140 mpg‑e 24.1 kWh/100 mi; 15.0 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Tesla Model Y AWD[51] | 2023 | 123 mpg‑e 27.4 kWh/100 mi; 17.0 kWh/100 km |

129 mpg‑e 26.1 kWh/100 mi; 16.2 kWh/100 km |

116 mpg‑e 29.1 kWh/100 mi; 18.1 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Tesla Model 3[56] Standard Range[57] | 2020 | 141 mpg‑e 23.9 kWh/100 mi; 14.9 kWh/100 km |

148 mpg‑e 22.8 kWh/100 mi; 14.2 kWh/100 km |

132 mpg‑e 25.5 kWh/100 mi; 15.9 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Hyundai Ioniq Electric[50][58] | 2017 | 136 mpg‑e 24.8 kWh/100 mi; 15.4 kWh/100 km |

150 mpg‑e 22.5 kWh/100 mi; 14.0 kWh/100 km |

122 mpg‑e 27.6 kWh/100 mi; 17.2 kWh/100 km |

(1) (4) | ||

| BMW i3 (60 A·h)[59][60] | 2014/15/16 | 124 mpg‑e 27.2 kWh/100 mi; 16.9 kWh/100 km |

137 mpg‑e 24.6 kWh/100 mi; 15.3 kWh/100 km |

111 mpg‑e 30.4 kWh/100 mi; 18.9 kWh/100 km |

(1) (3) (4) (5) | ||

| Scion iQ EV[61] | 2013 | 121 mpg‑e 27.9 kWh/100 mi; 17.3 kWh/100 km |

138 mpg‑e 24.4 kWh/100 mi; 15.2 kWh/100 km |

105 mpg‑e 32.1 kWh/100 mi; 19.9 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Tesla Model 3 Long Range AWD[62] | 2020 | 121 mpg‑e 27.9 kWh/100 mi; 17.3 kWh/100 km |

124 mpg‑e 27.2 kWh/100 mi; 16.9 kWh/100 km |

116 mpg‑e 29.1 kWh/100 mi; 18.1 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Chevrolet Bolt EV[63] | 2017 | 119 mpg‑e 28.3 kWh/100 mi; 17.6 kWh/100 km |

121 mpg‑e 27.9 kWh/100 mi; 17.3 kWh/100 km |

110 mpg‑e 30.6 kWh/100 mi; 19.0 kWh/100 km |

|||

| Chevrolet Spark EV[64] | 2014/15/16 | 119 mpg‑e 28.3 kWh/100 mi; 17.6 kWh/100 km |

128 mpg‑e 26.3 kWh/100 mi; 16.4 kWh/100 km |

109 mpg‑e 30.9 kWh/100 mi; 19.2 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| BMW i3 (94 A·h)[59] | 2017 | 118 mpg‑e 28.6 kWh/100 mi; 17.7 kWh/100 km |

129 mpg‑e 26.1 kWh/100 mi; 16.2 kWh/100 km |

106 mpg‑e 31.8 kWh/100 mi; 19.8 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Honda Fit EV[65] | 2013/14 | 118 mpg‑e 28.6 kWh/100 mi; 17.7 kWh/100 km |

132 mpg‑e 25.5 kWh/100 mi; 15.9 kWh/100 km |

105 mpg‑e 32.1 kWh/100 mi; 19.9 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Fiat 500e[66] | 2013/14/15 | 116 mpg‑e 29.1 kWh/100 mi; 18.1 kWh/100 km |

122 mpg‑e 27.6 kWh/100 mi; 17.2 kWh/100 km |

108 mpg‑e 31.2 kWh/100 mi; 19.4 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Volkswagen e-Golf[67] | 2015/16 | 116 mpg‑e 29.1 kWh/100 mi; 18.1 kWh/100 km |

126 mpg‑e 26.8 kWh/100 mi; 16.6 kWh/100 km |

105 mpg‑e 32.1 kWh/100 mi; 19.9 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Nissan Leaf (24 kW-h)[68] | 2013/14/15/16 | 114 mpg‑e 29.6 kWh/100 mi; 18.4 kWh/100 km |

126 mpg‑e 26.8 kWh/100 mi; 16.6 kWh/100 km |

101 mpg‑e 33.4 kWh/100 mi; 20.7 kWh/100 km |

(1) (6) | ||

| Mitsubishi i[69] | 2012/13/14/16 | 112 mpg‑e 30.1 kWh/100 mi; 18.7 kWh/100 km |

126 mpg‑e 26.8 kWh/100 mi; 16.6 kWh/100 km |

99 mpg‑e 34.0 kWh/100 mi; 21.2 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Nissan Leaf (30 kW-h)[68] | 2016 | 112 mpg‑e 30.1 kWh/100 mi; 18.7 kWh/100 km |

124 mpg‑e 27.2 kWh/100 mi; 16.9 kWh/100 km |

101 mpg‑e 33.4 kWh/100 mi; 20.7 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Fiat 500e[70] | 2016 | 112 mpg‑e 30.1 kWh/100 mi; 18.7 kWh/100 km |

121 mpg‑e 27.9 kWh/100 mi; 17.3 kWh/100 km |

103 mpg‑e 32.7 kWh/100 mi; 20.3 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Smart electric drive[71] | 2013/14/15/16 | 107 mpg‑e 31.5 kWh/100 mi; 19.6 kWh/100 km |

122 mpg‑e 27.6 kWh/100 mi; 17.2 kWh/100 km |

93 mpg‑e 36.2 kWh/100 mi; 22.5 kWh/100 km |

(1) (7) | ||

| Kia Soul EV[72] | 2015/16 | 105 mpg‑e 32.1 kWh/100 mi; 19.9 kWh/100 km |

120 mpg‑e 28.1 kWh/100 mi; 17.5 kWh/100 km |

92 mpg‑e 36.6 kWh/100 mi; 22.8 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Ford Focus Electric[73] | 2012/13/14/15/16 | 105 mpg‑e 32.1 kWh/100 mi; 19.9 kWh/100 km |

110 mpg‑e 30.6 kWh/100 mi; 19.0 kWh/100 km |

99 mpg‑e 34.0 kWh/100 mi; 21.2 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Tesla Model S AWD - 70D[49][74] | 2015/16 | 101 mpg‑e 33.4 kWh/100 mi; 20.7 kWh/100 km |

101 mpg‑e 33.4 kWh/100 mi; 20.7 kWh/100 km |

102 mpg‑e 33.0 kWh/100 mi; 20.5 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Tesla Model S AWD - 85D[49][75] & 90D[49][74] | 2015/16 | 100 mpg‑e 33.7 kWh/100 mi; 20.9 kWh/100 km |

95 mpg‑e 35.5 kWh/100 mi; 22.0 kWh/100 km |

106 mpg‑e 31.8 kWh/100 mi; 19.8 kWh/100 km |

(1) (8) | ||

| Tesla Model S (60 kW·h)[49][74] | 2014/15/16 | 95 mpg‑e 35.5 kWh/100 mi; 22.0 kWh/100 km |

94 mpg‑e 35.9 kWh/100 mi; 22.3 kWh/100 km |

97 mpg‑e 34.7 kWh/100 mi; 21.6 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Tesla Model S AWD - P85D[49][75] & P90D[49][74] | 2015/16 | 93 mpg‑e 36.2 kWh/100 mi; 22.5 kWh/100 km |

89 mpg‑e 37.9 kWh/100 mi; 23.5 kWh/100 km |

98 mpg‑e 34.4 kWh/100 mi; 21.4 kWh/100 km |

(1) (8) | ||

| Tesla Model X AWD – 90D[76] | 2016 | 92 mpg‑e 36.6 kWh/100 mi; 22.8 kWh/100 km |

90 mpg‑e 37.5 kWh/100 mi; 23.3 kWh/100 km |

94 mpg‑e 35.9 kWh/100 mi; 22.3 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Tesla Model X AWD – P90D[76] | 2016 | 89 mpg‑e 37.9 kWh/100 mi; 23.5 kWh/100 km |

89 mpg‑e 37.9 kWh/100 mi; 23.5 kWh/100 km |

90 mpg‑e 37.5 kWh/100 mi; 23.3 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Tesla Model S (85 kW·h)[77] | 2012/13/14/15 | 89 mpg‑e 37.9 kWh/100 mi; 23.5 kWh/100 km |

88 mpg‑e 38.3 kWh/100 mi; 23.8 kWh/100 km |

90 mpg‑e 37.5 kWh/100 mi; 23.3 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Mercedes-Benz B-Class Electric Drive[78] | 2014/15/16 | 84 mpg‑e 40.1 kWh/100 mi; 24.9 kWh/100 km |

85 mpg‑e 39.7 kWh/100 mi; 24.6 kWh/100 km |

83 mpg‑e 40.6 kWh/100 mi; 25.2 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Toyota RAV4 EV[79] | 2012/13/14 | 76 mpg‑e 44.3 kWh/100 mi; 27.6 kWh/100 km |

78 mpg‑e 43.2 kWh/100 mi; 26.9 kWh/100 km |

74 mpg‑e 45.5 kWh/100 mi; 28.3 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| BYD e6[49][80] | 2012/13/14/15/16 | 63 mpg‑e 53.5 kWh/100 mi; 33.2 kWh/100 km |

61 mpg‑e 55.3 kWh/100 mi; 34.3 kWh/100 km |

65 mpg‑e 51.9 kWh/100 mi; 32.2 kWh/100 km |

(1) | ||

| Second gen Chevrolet Volt[49][81][82] Plug-in hybrid (PHEV) Electricity only |

2016 | 106 mpg‑e 31.8 kWh/100 mi; 19.8 kWh/100 km |

113 mpg‑e 29.8 kWh/100 mi; 18.5 kWh/100 km |

99 mpg‑e 34.0 kWh/100 mi; 21.2 kWh/100 km |

(1) (2) (9) | ||

| Volt, Gasoline only | 42 mpg | 43 mpg | 42 mpg | ||||

| Toyota Prius Eco (4th gen)[53] Hybrid electric vehicle (HEV) Gasoline-electric hybrid |

2016 | 56 mpg | 58 mpg | 53 mpg | (2) (10) | ||

| Ford Fusion AWD A-S6 2.0L[49][83] Gasoline-powered (Average new vehicle) |

2016 | 25 mpg | 22 mpg | 31 mpg | (2) (11) | ||

| Notes: All estimated fuel economy based on 15,000 miles (24,000 km) annual driving, 45% highway and 55% city (1) Conversion 1 gallon of gasoline=33.7 kW·h. | |||||||

Plug-in hybrids

[edit]Plug-in hybrid car energy efficiency

Fuel cell vehicles

[edit]The following table compares EPA's fuel economy expressed in miles per gallon gasoline equivalent (MPGe) for the two models of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles rated by the EPA as of September 2021[update], and available in California.[86]

| Comparison of fuel economy expressed in MPGe for hydrogen fuel cell vehicles available for sale or lease in California and rated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as of September 2021[update][86] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Model year | Combined fuel economy |

City fuel economy |

Highway fuel economy |

Range | Annual fuel cost | |

| Hyundai Nexo | 2019–2021 | 61 mpg-e | 65 mpg-e | 58 mpg-e | 380 mi (610 km) | ||

| Toyota Mirai | 2016–20 | 66 mpg-e | 66 mpg-e | 66 mpg-e | 312 mi (502 km) | ||

| Toyota Mirai | 2021 | 74 mpg-e | 76 mpg-e | 71 mpg-e | 402 mi (647 km) | ||

| Notes: One kg of hydrogen is roughly equivalent to one U.S. gallon of gasoline. | |||||||

Conversion using GGE

[edit]The same method can be applied to any other alternative fuel vehicle when that vehicle's energy consumption is known. Generally the energy consumption of the vehicle is expressed in units other than W·h/mile, or Btu/mile so additional arithmetic is required to convert to a gasoline gallon equivalent (GGE), using 33.7 kWh / gallon = 114989.17 btu / gallon.[8]

Hydrogen example with GGE

[edit]The 2008 Honda FCX Clarity is advertised to have a vehicle consumption of 72 mi/kg-H

2.[87] Hydrogen at atmospheric pressure has an energy density of 120 MJ/kg (113,738 BTU/kg),[88] by converting this energy density to a GGE, it is found that 1.011 kg of hydrogen is needed to meet the equivalent energy of one gallon of gasoline. This conversion factor can now be used to calculate the MPGe for this vehicle.

- ,

Life cycle assessment

[edit]Pump/Well-to-wheel

[edit]EPA's miles per gallon equivalent metric shown in the window sticker does not measure a vehicle's full cycle energy efficiency or well-to-wheel life cycle. Rather, the EPA presents MPGe in the same manner as MPG for conventional internal combustion engine vehicles as displayed in the Monroney sticker, and in both cases the rating only considers the pump-to-wheel or wall-to-wheel energy consumption, i.e. it measures the energy for which the owner usually pays. For EVs the energy cost includes the conversions from AC from the wall used to charge the battery[39] The EPA ratings displayed in window stickers do not account for the energy consumption upstream, which includes the energy or fuel required to generate the electricity or to extract and produce the liquid fuel; the energy losses due to power transmission; or the energy consumed for the transportation of the fuel from the well to the station.[14][40]

Petroleum-equivalency factor (PEF) – a CAFE metric

[edit]In 2000 the United States Department of Energy (DOE) established the methodology for calculating the petroleum-equivalent fuel economy of electric vehicles based on the well-to-wheel (WTW) gasoline-equivalent energy content of electricity (). The methodology considers the upstream efficiency of the processes involved in the two fuel cycles, and considers the national average electricity generation and transmission efficiencies because a battery electric vehicle burns its fuel (mainly fossil fuels) off-board at the power generation plant.[14] This methodology is used by carmakers to estimate credits into their overall Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) for manufacturing electric drive vehicles.[13]

The petroleum equivalent fuel economy of electric vehicles is determined by the following equations:[14]

-

- where:

- = Petroleum-equivalent fuel economy

- = Gasoline-equivalent energy content of electricity factor

- = "Fuel content" factor or incentive factor. DoE selected a value of 1⁄0.15 to retain consistency with existing regulatory and statutory procedures, and to provide a similar treatment to manufacturers of all types of alternative fuel vehicles[89]

- = Petroleum-fueled accessory factor; this is equal to 1 if the electric drive vehicle does not have petroleum-powered accessories installed, and 0.90 if it does.

- = Driving pattern factor; this is equal to 1, as DoE considered that electric vehicles eligible for inclusion in CAFE will offer capabilities, perhaps excepting driving range, similar to those of conventional vehicles.

- where:

The gasoline-equivalent energy content of electricity factor, abbreviated as , is defined as:

-

- where:

- = U.S. average fossil-fuel electricity generation efficiency = 0.328[90]

- = U.S. average electricity transmission efficiency = 0.924[90]

- = Petroleum refining and distribution efficiency = 0.830[90]

- = Watt hours of energy per gallon of gasoline conversion factor = 33,705 Wh/US gal (115,006 BTU/US gal)[90]

- where:

is computed as:

This computation accounts for the well-to-wall losses resulting from the extraction of crude oil and refinement into gasoline (Tp), conversion to electricity (Tg), and the transmission grid (Tt); in summary, the total amount of useful electrical energy that can be extracted from gasoline is just 36.5% of its total theoretical stored energy.[90] Substituting the numerical values into the first equation,

As noted above, when and are 1, as they would be for a pure-electric vehicle, .

- Examples

In the example provided by the US DoE in its final rule, an electric car with an energy consumption of 265 Watt hour per mile in urban driving, and 220 Watt hour per mile in highway driving, results in a petroleum-equivalent fuel economy of 335.24 miles per gallon, based on a driving schedule factor of 55 percent urban, and 45 percent highway, and using a petroleum equivalency factor of 82,049 Watt hours per gallon.[14]

In 2009, the Monroney sticker for the Mini E rated the wall-to-wheel energy consumption at 33 / 36 kWh/100 mi (102.1 / 93.6 mpg‑e) for the city and highway driving cycles, respectively.[90] The petroleum-equivalent fuel economy is 239 MPGPE, assuming a 55%/45% urban/highway split.

For comparison, the 2017 Chevrolet Bolt EV has a rated (wall-to-wheel) consumption of 128 / 110 mpg‑e (263 / 306 Wh/mi) listed on the Monroney sticker for the urban/highway driving cycles, respectively.[63] The petroleum-equivalent fuel economy for the Bolt, using the DoE rule to consider well-to-wall energy losses, is 284 MPGPE, computed using the same 55%/45% urban/highway split.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ EPA, OAR, OTAQ, US (13 October 2016). "Electric Vehicles – Learn More About the New Label | U.S. EPA". U.S. EPA. Archived from the original on 2018-02-01. Retrieved 2018-01-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Paul Seredynski (2010-12-21). "Decoding Electric Car MPG: With Kilowatt-Hours, Small Is Beautiful". Edmunds. Edmunds.com. Archived from the original on 2011-01-02. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ a b c d "Fuel Economy Label". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2011-02-14. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ a b "EIA – Electricity Data". www.eia.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-08-08. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- ^ a b "Natural Gas Residential Price". www.eia.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-07-09. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

EPAFEG2017MYwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "The True Cost of Powering an Electric Car". Edmunds. Archived from the original on 2024-05-15. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- ^ a b c d U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (May 2011). "New Fuel Economy and Environment Labels for a New Generation of Vehicles". EPA. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ^ a b c Nick Bunkley (2010-11-22). "Nissan Says Its Electric Leaf Gets Equivalent of 99 mpg (miles/gal, miles per galon)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ a b c d e Fred Meier (2010-11-24). "Volt is rated 93 mpg on electricity alone, 37 mpg on gas generator". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2010-11-27. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ a b c d EPA (May 2011). "Fact Sheet: New Fuel Economy and Environment Labels for a New Generation of Vehicles" (PDF). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-28. Retrieved 2011-05-25.EPA-420-F-11-017

- ^ a b "EPA, DOT unveil the next generation of fuel economy labels". Green Car Congress. 2011-05-25. Archived from the original on 2011-05-29. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g Paul Weissler (2009-07-06). "Many factors figure in fuel-economy calculation for electric vehicles". Automotive Engineering International Online (SAE International Magazine). Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Research, Development, and Demonstration Program; Petroleum-Equivalent Fuel Economy Calculation; Final Rule" (PDF). 2000-06-12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-12-10. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ a b Pub. L. 100–494: Alternative Motor Fuels Act of 1988

- ^ a b c d e Report to Congress on Effects of the Alternative Motor Fuels Act CAFE Incentives Policy (PDF) (Report). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. March 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ a b "The Corporate Average Fuel Economy Program (CAFE) – Background: AMFA CAFE Credits". National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Archived from the original on June 12, 2002.

- ^ "Handbook 44 Appendix D -Definitions" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-09. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Electric Transportation Applications (1996). "Test Reports for Vehicles by Manufacturer and Model: General Motors EV1" (PDF). Idaho National Laboratory, U.S. DoE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Electric Transportation Applications (1999). "Test Reports for Vehicles by Manufacturer and Model: 1999 General Motors EV1 w/NiMH" (PDF). Idaho National Laboratory, U.S. DoE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Electric Transportation Applications (1996). "Test Reports for Vehicles by Manufacturer and Model: Toyota RAV4 EV" (PDF). Idaho National Laboratory, U.S. DoE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-02-21. Energy use averaged 2.5 miles per AC kWh (0.4 AC kWh per mile)

- ^ Electric Transportation Applications (March 2000). "Field Operations Program Toyota RAV4 (NiMH) – Accelerated Reliability Testing – Final Report" (PDF). Idaho National Laboratory, US DoE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-02-21. Energy use averaged 2.5 miles per AC kWh (0.4 AC kWh per mile)

- ^ Electric Transportation Applications (1997). "Test Reports for Vehicles by Manufacturer and Model: 1998 Ford Ranger EV" (PDF). Idaho National Laboratory, U.S. DoE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Electric Transportation Applications (1997). "Test Reports for Vehicles by Manufacturer and Model: 1997 Chevrolet S-10 Electric" (PDF). Idaho National Laboratory, US DoE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Sperling, Daniel and Deborah Gordon (2009). Two billion cars: driving toward sustainability. Oxford University Press, New York. pp. 22–26. ISBN 978-0-19-537664-7.

- ^ Sherry Boschert (2006). Plug-in Hybrids: The Cars that will Recharge America. New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, Canada. pp. 15–28. ISBN 978-0-86571-571-4.

- ^ a b c "Why Are the VOLT and LEAF EVs Measured in Miles per Gallon". Electric Vehicle News. 2009-08-15. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ "Press Release: Automotive X Prize Announces Draft Guidelines for Competition to Inspire Super-Efficient Vehicles". X Prize Foundation. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ^ "Press Release: Consumer Reports to Adopt MPGe Measure for Fuel Economy". X Prize Foundation. Retrieved 2010-12-07.

- ^ a b Office of Transportation and Air Quality, EPA, and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Us DoT (September 2010). "Environmental Protection Agency Fuel Economy Label – Final Report" (PDF). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-13. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Brad Berman (2009-07-29). "Confusion Over MPG Ratings for Electric Cars". HybridCars.com. Archived from the original on 2014-03-15. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- ^ Don Sherman (2008-11-13). "Cranking the Volt to 100 M.P.G." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2016-07-20. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- ^ "2009 Tesla Roadster window sticker". The New York Times. 2008-11-13. Archived from the original on 2014-03-28. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- ^ "EPA and NHTSA Propose Changes to the Motor Vehicle Fuel Economy Label" (PDF). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. August 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-13. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ Jim Motavalli (2010-08-30). "E.P.A. Develops Grading System for New Car Stickers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2024-05-15. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ Assessment of Fuel Economy Technologies for Light-duty Vehicles. The National Academies Press. 2011. p. 12. doi:10.17226/12924. ISBN 978-0-309-15607-3. Archived from the original on 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- ^ "Understanding the New Fuel Economy and Environment Labels" (PDF). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-15. Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- ^ "FE and Environment Label – Brochure" (PDF). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-18. Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- ^ a b c Michael Duoba; R. Carlson; J. Wu. "TEST PROCEDURES AND BENCHMARKING Blended-Type and EV-Capable Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles" (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-24. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- ^ a b MIT Electric Vehicle Team (March 2008). "Fuel Economy Numbers for Electric Vehicles" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- ^ GREET model retrieved 2011 01 20

- ^ U.S. Department of Energy. "Fuel Economy Guide Model Year 2018" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-02-05. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- ^ "SAE Approves Method for Rating Plug-In Hybrid MPG and Emissions". EV World. 2010-07-01. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ^ "Recommended Practice for Measuring the Exhaust Emissions and Fuel Economy of Hybrid-Electric Vehicles, Including Plug-in Hybrid Vehicles". SAE International. 2010-06-08. Archived from the original on 2024-05-15. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ^ a b Nick Bunkley (2010-11-24). "3 Numbers to Rate Volt's Fuel Economy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-01-30. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- ^ Nick Bunkley & Bill Vlasic (2010-10-14). "Plug-In Cars Pose Riddle for E.P.A." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-01-30. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- ^ "Volt receives EPA ratings and label: 93 mpg-e all-electric, 37 mpg gas-only, 60 mpg-e combined". Green Car Congress. 2010-11-24. Archived from the original on 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- ^ a b Fuel Economy Guide, Model Year 2015 (PDF) (Report). United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2014. pp. 31–34. Retrieved 25 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Fuel Economy Guide, Model Year 2016 (PDF) (Report). United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2025. See pp. 27–28 for all-electric vehicles and pp. 30–31 for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. The average 2016 vehicle gets 25 mpg

- ^ a b c Fuel Economy Guide, Model Year 2017 (PDF) (Report). United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2016. pp. 32–36. Retrieved 25 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Fuel Economy Guide, Model Year 2023 (PDF) (Report). United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2022. p. 11. Retrieved 25 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d e U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "Fueleconomy.gov's Top Fuel Sippers (EPA Ratings, All Years)". fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06. Excludes all-electric vehicles. Click on the tab "Top Fuel Sippers (EPA Ratings, All Years)" - The 2016 Volt has a combined fuel economy of 77 mpg-e. The BMW i3 REx has a combined fuel economy of 88 mpg-e, and ranks as the most efficient EPA-certified current year vehicle with a gasoline engine.

- ^ a b U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-18). "Compare Side-by-Side - 2015 Toyota Prius, 2016 Toyota Prius and 2016 Toyota Prius Eco". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-18. The average 2016 vehicle gets 25 mpg.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-08-14). "2016 Best and Worst Fuel Economy Vehicles - (excluding electric vehicles)". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-08-17. See the tab "Cars excl. EVs" – The Prius c is the most fuel efficient in the compact class and the conventional Prius is the most fuel efficient in the midsize class, and both rank ahead of the most fuel efficient in any other clars.

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy. "How Vehicles Are Tested". www.fueleconomy.gov.

- ^ "2020 Tesla Model 3 Standard Range Plus". www.fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2020-05-10). "2020 Model 3 SR+". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2016-11-18). "Compare Side-by-Side: 2017 Hyundai Ioniq Electric". fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- ^ a b United States Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2016-09-29). "Compare Side-by-Side: 2015 BMW i3 REX, 2016 BMW i3 REX, 2017 BMW i3 REX (94 Amp-hour battery), and 2017 BMW i3 BEV (94 Amp-hour battery)". fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "Compare Side-by-Side: 2014 BMW i3 BEV". fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2013 Scion iQ EV". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2020-05-10). "2020 Model 3 LR AWD". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- ^ a b Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy and U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and (2016-09-20). "Compare Side-by-Syde - 2017 Chevrolet Bolt". fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-20.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2014 Chvevrolet Spark EV". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2013 Honda Fit EV". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2013 Fiat 500e". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2015 Volkswagen e-Golf". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ a b U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "Compare side by side: 2013 Nissan Leaf/2014 Nissan Leaf/2015 Nissan Leaf/2016 Nissan Leaf (24 kW-hr battery pack)/2016 Nissan Leaf (30 kW-hr battery pack)". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2011–12 Electric Vehicles- 2012 Mitsubishi i-MiEV". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2016 Fiat 500e". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2013 smart fortwo electric drive coupe". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2015 Kia Soul Electric". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2012 Ford Focus BEV". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ a b c d U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "Compare Side-by-Side - 2015 Tesla Model S 60 kW-hr/AWD - 70D/AWD - 90D/AWD - P90D". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ a b U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2015 Tesla Model S (85 kW-hr battery pack); 2014 Tesla Model S AWD (85 kW-hr battery pack); 2015 Tesla Model S AWD - 85D; and 2015 Tesla Model S AWD - P85D". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ a b U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2016 Tesla Model X AWD - 90D and P90D". Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2012 Tesla Model S". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2014/2015/2016 Mercedes-Benz B-Class Electric Drive". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "2012/2013/2014 Toyota RAV4 EV". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "Compare Side-by-Side: 2012/13/14/15 BYD e6". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "Compare Side-by-Side - 2016/2015 Chevrolet Volt". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ Eric Loveday (2015-09-01). "Detailed Look At 2016 Chevrolet Volt EPA Ratings". InsideEVs.com. Retrieved 2015-09-02.

- ^ a b United States Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2015-12-04). "Compare Side-by-Side: 2016 Ford Fusion AWD, 2016 Honda Accord, 2016 Toyota Camry, and 2016 Toyota RAV4 AWD". fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ a b U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2016-11-18). "Most Efficient EPA Certified Vehicles". fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2016-11-19. Current Model Year excludes all-electric vehicles.

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (2014-07-04). "Compare Side-by-Side: 2014 BMW i3 BEV & 2014 BMW i3 REx". fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ^ a b United States Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy (September 2021). "Compare Fuel Cell Vehicles". fueleconomy.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-08-14. Retrieved 2021-09-13. One kg of hydrogen is roughly equivalent to one U.S. gallon of gasoline.

- ^ "Honda FCX Clarity Fuel Cell Vehicle Lease Program Begins with First Customer Delivery". Honda. 2008. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ "HFCIT Hydrogen Storage: Basics". United States Department of Energy. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ Pub. L. 100–494: Alternative Motor Fuels Act of 1988

- ^ a b c d e f Fleming, Bill (December 2009). "Electric vehicle EPA fuel-economy calculations [Automotive Electronics". IEEE Vehicular Technology Magazine. 4 (4). IEEE: 4–8. doi:10.1109/MVT.2009.934662. ISSN 1556-6072.

External links

[edit]- Model Year 2014 Fuel Economy Guide, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Energy, April 2014.

Miles per gallon gasoline equivalent

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Purpose

Core Concept of MPGe

Miles per gallon gasoline equivalent (MPGe) is a unit of measurement developed by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to express the fuel efficiency of vehicles powered by electricity, hydrogen, or other alternative fuels in terms equivalent to the miles traveled per gallon of gasoline.[1] It standardizes comparisons by converting the energy consumed from non-liquid fuels into the equivalent volume of gasoline based on energy content, where one gallon of gasoline contains approximately 33.7 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of energy.[3] This metric focuses solely on the vehicle's onboard energy use and efficiency, excluding upstream production losses such as those in electricity generation or fuel refining.[9] The core calculation for battery electric vehicles derives MPGe by dividing the distance traveled by the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline divided by the actual energy consumed. Specifically, for an electric vehicle, MPGe equals 33,700 watt-hours (Wh) per gallon divided by the vehicle's energy consumption in Wh per mile, yielding a value that reflects how many miles the vehicle can travel on the energy in one gallon of gasoline.[1] For example, a vehicle consuming 34 Wh per mile achieves approximately 99 MPGe (33,700 / 34 ≈ 99).[10] In laboratory testing, separate city, highway, and combined MPGe values are determined using standardized drive cycles, analogous to traditional MPG testing for gasoline vehicles.[1] For plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, MPGe applies to the electric-only mode, while gasoline mode uses standard MPG; combined ratings may blend both depending on assumed electric driving share.[11] This equivalence enables direct efficiency comparisons across powertrains but assumes equal energy value regardless of source, potentially overstating real-world advantages if grid electricity includes inefficiencies not captured in the metric.[9] The EPA adopted MPGe in 2010 for labeling to inform consumers, with values displayed on Monroney stickers for alternative fuel vehicles.[3]Intended Role in Vehicle Efficiency Comparisons

Miles per gallon gasoline equivalent (MPGe) is designed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to enable direct comparisons of energy efficiency between vehicles using electricity, alternative fuels, or hybrid powertrains and those powered by conventional gasoline engines. By expressing efficiency in terms equivalent to miles traveled per gallon of gasoline, MPGe translates the energy consumption of non-liquid fuels into a familiar metric, facilitating consumer understanding and cross-technology evaluation.[1][9] This standardization addresses the limitation of traditional miles per gallon (MPG), which applies only to liquid fuels, by basing calculations on the energy content of gasoline—approximately 33.7 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per U.S. gallon. For electric vehicles (EVs), MPGe reflects the distance traveled per equivalent gallon of energy drawn from the electrical grid, incorporating charging inefficiencies typically around 85-90%. Thus, a vehicle rated at 100 MPGe achieves the same distance on 33.7 kWh of electricity (after charging losses) as a gasoline vehicle does on one gallon of fuel at 100 MPG.[1] In practice, MPGe appears on EPA fuel economy labels for plug-in electric vehicles and hybrids, alongside estimated ranges and costs, to aid purchasing decisions by quantifying efficiency gains from electric propulsion—often 2-3 times higher than gasoline counterparts due to superior drivetrain efficiency. For model year 2024 EVs, combined MPGe ratings range from 53 to 140, compared to 9-57 MPG for gasoline vehicles including hybrids, underscoring the metric's role in highlighting relative performance.[12] MPGe also informs regulatory compliance, such as Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, where alternative fuel vehicles' contributions are calculated using equivalent values to promote fleet-wide efficiency improvements without penalizing diverse technologies. However, as a vehicle-centric measure, it focuses on tank-to-wheel or wall-to-wheel efficiency, excluding upstream production losses like grid generation or fuel refining, which EPA documentation specifies as outside its comparative scope to emphasize end-use performance.[1]Historical Development

Origins in Alternative Fuels Legislation (1988–1994)

The Alternative Motor Fuels Act of 1988 (AMFA), enacted as Public Law 100-494 on October 14, 1988, established initial federal incentives for automobile manufacturers to produce vehicles capable of operating on alternative fuels such as methanol, ethanol, and natural gas, aiming to reduce dependence on imported petroleum.[13] To facilitate compliance with Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, AMFA directed the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) to develop special fuel economy calculation methods for alternative fuel vehicles (AFVs).[14] These methods involved deriving a petroleum-equivalent fuel economy value, which adjusted the measured miles per gallon of the alternative fuel based on its lower energy content relative to gasoline, thereby allowing manufacturers to earn CAFE credits as if the vehicles achieved comparable or enhanced efficiency in gasoline terms.[15] Under AMFA's provisions, effective for model year 1993, dedicated AFVs—those designed solely for alternative fuels—received CAFE credits by multiplying their actual alternative fuel efficiency (in miles per gallon equivalent) by factors escalating from 0.90 in 1993 to 1.2 by 2004, effectively deeming them to meet or exceed gasoline vehicle standards on an energy-equivalent basis.[13] This equivalence was computed using the British thermal unit (Btu) content of the fuels, with gasoline standardized at approximately 114,000–125,000 Btu per gallon, to normalize comparisons and incentivize production despite the volumetric inefficiencies of fuels like methanol (about 64,000 Btu per gallon).[14] Dual-fueled vehicles, capable of running on either alternative fuels or gasoline, were credited with the higher of their two fuel economy values for CAFE averaging, further boosting manufacturer incentives.[15] The legislation required biennial reports to Congress on AFV performance and market impacts, highlighting early challenges such as limited refueling infrastructure and higher vehicle costs, but emphasizing the equivalence metric's role in policy-driven fuel diversification.[14] By 1994, these calculations gained further standardization with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) defining the gasoline gallon equivalent (GGE) for compressed natural gas as 5.660 pounds, equivalent to one gallon of gasoline's energy content, to support consistent measurement across fuels in commerce and efficiency ratings. This built directly on AMFA's framework, enabling more precise CAFE crediting for natural gas vehicles and laying conceptual groundwork for broader application to non-liquid fuels, though implementation remained limited to a few thousand AFVs annually due to technological and economic barriers.[16] The period's developments prioritized empirical energy content data over unsubstantiated environmental claims, focusing on verifiable Btu equivalences to avoid distorting actual vehicle performance metrics.[14]Refinement for Non-Petroleum Fuels (2000–2007)

In June 2000, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) revised its regulations under the Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Research, Development, and Demonstration Program to establish a petroleum-equivalency factor (PEF) and standardized procedures for calculating the petroleum-equivalent fuel economy of electric vehicles (EVs), addressing the need for consistent measurement of non-petroleum fuel efficiency in federal programs like Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE).[17] This refinement built on earlier legislative mandates by incorporating empirical adjustments for real-world energy conversion inefficiencies, ensuring the metric reflected the petroleum displacement potential of electricity-powered vehicles without assuming grid generation sources.[17] The updated PEF formula was defined as , where represented the adjusted gasoline-equivalent energy content (calculated as 12,307 watt-hours per gallon using factors for transmission efficiency , torque converter efficiency , and pumping efficiency , derived from the base gasoline energy of 33,705 watt-hours per gallon); was the fuel content factor accounting for an assumed average internal combustion engine thermal efficiency of 15 percent; was the accessory factor (1.00 for vehicles without petroleum-powered accessories, or 0.90 otherwise); and was the driving pattern factor (set at 1.00).[17] This yielded PEF values of 82,049 watt-hours per gallon for EVs without petroleum accessories and 73,844 watt-hours per gallon with them, enabling fuel economy calculations as .[17] The adjustments prioritized causal energy pathways, emphasizing delivered propulsion energy over raw input, to incentivize EV adoption while aligning with statutory goals under 49 U.S.C. § 32905 for alternative fuel equivalence.[17] These changes simplified prior ad hoc methods, promoting uniformity in CAFE compliance for dedicated EVs using electricity as a non-petroleum fuel, though the metric did not extend formally to hybrid systems or other alternatives like hydrogen until later frameworks.[17] No substantive revisions to the PEF occurred through 2007, as the formula's empirical basis—rooted in laboratory-derived efficiencies and national energy data—remained stable amid limited commercial EV deployment.[18] Critics noted the fixed 15 percent efficiency assumption underrepresented variability in gasoline engine performance, potentially overstating EV equivalence in petroleum savings, but DOE justified it via aggregate fleet data to avoid overcomplication.[17]Standardization and EPA Adoption (2010–Present)

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) first implemented the miles per gallon gasoline equivalent (MPGe) metric on consumer fuel economy labels in November 2010 for model year 2011 vehicles, marking its debut on the Nissan Leaf electric vehicle and Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid.[19] This introduction coincided with the proposal for revisions to motor vehicle fuel economy labels, published in the Federal Register on September 23, 2010, which aimed to provide comparable efficiency metrics for alternative fuel vehicles alongside traditional gasoline models.[20] The MPGe calculation standardized the energy content of one gallon of gasoline at 33,705 watt-hours, enabling direct equivalence for electricity, hydrogen, and other fuels in terms of miles traveled per unit energy.[1] A final rule issued on May 25, 2011, formalized the label requirements, mandating MPGe display for electric vehicles (EVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), and fuel cell vehicles starting with model year 2012, while extending redesigned labels to all new vehicles to include annual fuel cost estimates and greenhouse gas ratings.[21] This adoption standardized MPGe as the primary consumer-facing efficiency measure for non-petroleum vehicles, derived from EPA's laboratory 2-cycle (city/highway) testing protocols adjusted for charging losses in EVs and PHEVs, typically assuming 85-90% grid-to-battery efficiency.[3] By integrating MPGe into the Monroney sticker, the EPA facilitated cross-fuel comparisons, though the metric's fixed energy equivalence has drawn scrutiny for not accounting for variable upstream production efficiencies in electricity generation versus gasoline refining. From 2011 onward, MPGe ratings proliferated as EV and PHEV adoption grew, with the EPA applying the metric consistently across vehicle types, including hydrogen fuel cell models using gasoline gallon equivalents (GGE) where one kg of hydrogen equates to approximately 1.011 gallons of gasoline. Updates to related methodologies persisted; notably, the U.S. Department of Energy revised the petroleum equivalency factor (PEF) in March 2024, which influences CAFE compliance calculations for alternative fuels but remains distinct from the fixed 33.7 kWh/gallon basis for consumer MPGe labels.[22] This distinction underscores MPGe's role as a static consumer benchmark rather than a dynamic regulatory tool, with EPA maintaining the original standardization to prioritize simplicity in vehicle comparisons despite evolving energy market dynamics.[1]Calculation and Methodology

Energy Content Equivalence

The energy content equivalence in miles per gallon gasoline equivalent (MPGe) standardizes the comparison of vehicle efficiency across fuel types by converting the energy delivered from alternative sources into the equivalent volume of gasoline based on lower heating values. For electricity used in battery electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines 33.7 kilowatt-hours (kWh), or 33,705 watt-hours (Wh), as the electrical energy equivalent to one U.S. gallon of gasoline. This factor originates from the approximate lower heating value of gasoline at 115,000 British thermal units (BTU) per gallon, where 1 kWh equals 3,412 BTU, yielding the standardized conversion without adjustments for production or transmission losses in this baseline metric.[1][4] In the MPGe formula for electric vehicles, efficiency is computed as , where represents the vehicle's energy consumption in Wh per mile under standardized laboratory conditions, often incorporating factors for motor efficiency () and other drivetrain elements (). This approach equates the propulsion energy, enabling direct numerical comparison to conventional gasoline vehicles' miles per gallon (MPG), though it assumes parity in end-use energy without embedding upstream petroleum equivalency adjustments used in regulatory compliance like Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards. For instance, an electric vehicle consuming 300 Wh per mile achieves approximately 112 MPGe (), highlighting superior drivetrain efficiency typical of electric motors over internal combustion engines.[1][19] For hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, equivalence relies on the gasoline gallon equivalent (GGE), where the U.S. Department of Energy sets 1 GGE as approximately 1.011 kilograms of hydrogen based on energy content matching one gallon of gasoline's 33.7 kWh. Thus, MPGe is derived as , converting hydrogen's mass-based efficiency to a gasoline volume proxy; a vehicle achieving 72 miles per kg yields about 72.8 MPGe. This method similarly prioritizes delivered energy equivalence, though hydrogen's lower volumetric density requires larger storage compared to gasoline.[23][4]Laboratory Testing Protocols

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) determines MPGe ratings through standardized chassis dynamometer testing, where vehicles are restrained on rollers mimicking road resistance, including aerodynamic drag, tire rolling resistance, and drivetrain losses, while a human driver follows precise speed-time traces projected on a screen to replicate driving patterns.[24] These tests occur in controlled laboratory environments at facilities like the National Vehicle and Fuel Emissions Laboratory, ensuring repeatability and isolation from external variables such as weather or traffic.[25] For electric vehicles (EVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), protocols emphasize measuring onboard energy consumption—typically in kilowatt-hours (kWh) drawn from the battery—rather than liquid fuel volume, with electricity delivery simulated via onboard chargers or direct current metering.[26] EVs undergo testing per SAE J1634 procedures, adapted by the EPA, starting with a full charge followed by a multi-cycle test (MCT) comprising repeated Urban Dynamometer Driving Schedule (UDDS) cycles for city simulation until the battery state of charge reaches a 2% threshold or cannot sustain further operation, quantifying total AC or DC energy use in watt-hours per mile.[26] Highway testing employs the Highway Fuel Economy Driving Schedule (HFEDS), with constant-speed segments at 48.3 mph (77.8 km/h) and soaks between cycles to mimic idling.[27] Where MCT proves infeasible due to battery capacity limits, a single-cycle test (SCT) may be approved, focusing on one UDDS iteration with adjustments for range projection. Additional cycles, such as the US06 high-speed test or SC03 air-conditioning test, contribute to the optional 5-cycle methodology for refined estimates, particularly for labeling, by incorporating aggressive acceleration, high speeds, and accessory loads.[25] Cold-start procedures at 20°F (-6.7°C) for model year 2025 and later include two UDDS cycles with a 10-minute soak, requiring manufacturer data validation.[26] PHEVs follow SAE J1711 protocols, dividing tests into charge-depleting (CD) mode—prioritizing electric propulsion until battery depletion—and charge-sustaining (CS) mode, where the hybrid system maintains battery levels akin to conventional internal combustion engine testing.[26] CD phases use the 4-bag Federal Test Procedure (FTP, encompassing UDDS cold-start and transient segments) and HFET for city and highway, respectively, tracking both electricity (in kWh) and gasoline (in gallons) consumed until a net energy change threshold of 1% or fuel ratio stabilization.[27] CS mode employs standard FTP and HFET without battery recharge, treating the vehicle as a conventional hybrid. Utility factors—empirical weights reflecting typical electric range usage (e.g., from Table 1 in SAE J1711 for compliance)—blend CD and CS results, with EPA adjustments for labeling to account for real-world charging frequency.[26] All tests incorporate key-off soaks (e.g., 15 seconds between UDDS and HFEDS) and preconditioning runs to stabilize vehicle systems.[26] Combined MPGe derives from 55% city and 45% highway weighting of raw test data, with a 0.7 adjustment factor applied to projected ranges for EVs to reflect in-use degradation from factors like battery aging and non-ideal conditions, though this multiplier has drawn scrutiny for understating lab-derived efficiencies relative to empirical road data.[28] Protocols prioritize traceability, with raw data logged via onboard diagnostics and post-processing per 40 CFR Part 600, ensuring MPGe reflects energy efficiency under controlled, repeatable conditions rather than variable consumer behaviors.[26]Adjustments for Electricity and Charging Inefficiencies