Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

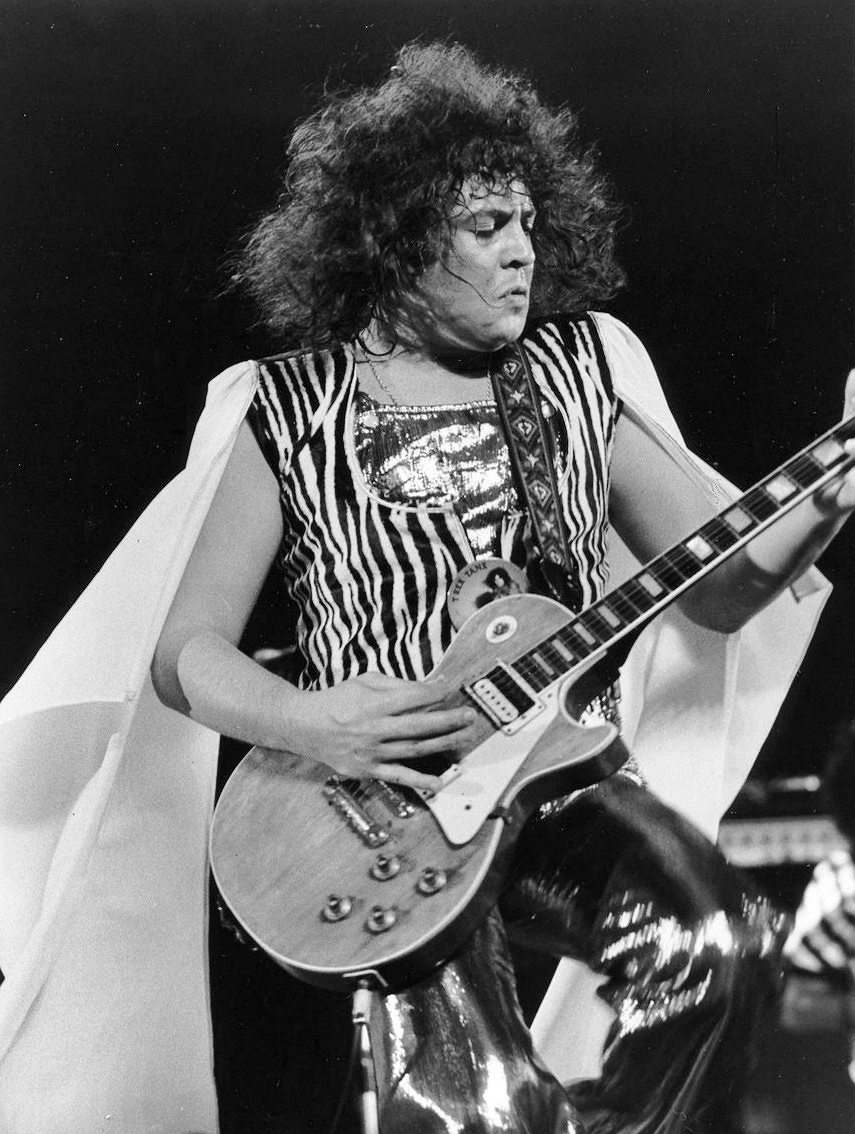

Marc Bolan

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Marc Bolan (/ˈboʊlən/ BOH-lən; born Mark Feld; 30 September 1947 – 16 September 1977) was an English guitarist, singer-songwriter and poet. He was a pioneer of the glam rock movement in the early 1970s with his band T. Rex.[1] Bolan strongly influenced artists of many genres, including glam rock, punk, post-punk, new wave, indie rock, Britpop and alternative rock. He was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2020 as a member of T. Rex.[2]

In the late 1960s, he rose to fame as the founder and leader of the psychedelic folk band Tyrannosaurus Rex, with whom he released four critically acclaimed albums and had one minor hit, "Debora". Bolan had started as an acoustic singer-writer before heading into electric music prior to the recording of T. Rex's first single "Ride a White Swan", which went to number two in the UK singles chart.[3] From 1970 to 1973, T. Rex achieved a level of popularity in the UK comparable to the Beatles, with a run of eleven top ten singles, four of which reached number one: "Hot Love", "Get It On", "Telegram Sam" and "Metal Guru". The 1971 album Electric Warrior, with all songs written by Bolan, received critical acclaim, reached number 1 in the UK and became a landmark album in glam rock. From 1973, he started marrying rock with other influences, including funk, soul, gospel, disco and R&B.

Bolan died in a car crash in 1977. A memorial stone and bust of Bolan, Marc Bolan's Rock Shrine, was unveiled at the site where he died in Barnes, west London. His musical influence as guitarist and songwriter is profound; he inspired many later acts over the following decades. Bolan's March 1971 appearance on the BBC's music show Top of the Pops, wearing glitter on his face, performing the UK chart topper "Hot Love" is cited as the start of the glam rock movement.[4]

Music critic Ken Barnes called Bolan "the man who started it all".[5] The 1971 album Electric Warrior has been described by AllMusic as "the album that essentially kick-started the UK glam rock craze".[6] Producer Tony Visconti, who worked with Bolan during his heyday, stated: "What I saw in Marc Bolan had nothing to do with strings, or very high standards of artistry; what I saw in him was raw talent. I saw genius. I saw a potential rock star in Marc – right from the minute, the hour I met him."

Early life

[edit]

Bolan was born Mark Feld at Hackney Hospital and grew up at 25 Stoke Newington Common, in the borough of Hackney, east London, the second child of Simeon ("Sid") Feld (1920–1991), a cosmetics salesman and former lorry driver, and Phyllis Winifred (née Atkins; 1927–1991), who ran a stall at Berwick Street Market in Soho. His father was an Ashkenazi Jew with roots in Russia and Poland, while his mother was English, originally from Fulham.[7][8] Moving to Wimbledon, southwest London, he fell in love with the rock and roll of Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, Arthur Crudup and Chuck Berry, and hung around coffee bars such as the 2i's in Soho.[9]

Bolan was a pupil at Northwold Primary School, Upper Clapton. At the age of nine, he was given his first guitar and began a skiffle band. While at school, he played guitar in "Susie and the Hula Hoops", a trio whose vocalist was a 12-year-old Helen Shapiro. During lunch breaks at school, he would play his guitar in the playground to a small audience of friends. At 15, he was expelled from school;[10] according to one of his friends: "He'd done something wrong and he went to see the headmaster, or the deputy headmaster, Mr. Pearson. He said he was going to give him the cane and Mark said no. He told him to hold out his hand and Mark nutted him."[11]

He appeared as an extra in an episode of the television show Orlando, dressed as a mod. Bolan briefly joined a modelling agency and became a "John Temple Boy", appearing in a clothing catalogue for the menswear store. He was a model for the suits in their catalogues as well as for cardboard cut-outs to be displayed in shop windows. In 1962, Town magazine featured him under the name Mark Feld as an early example of the mod movement in a photo spread orchestrated by Evening Standard columnist Angus McGill.[12][13]

Music career

[edit]1964–1967: Early career

[edit]In 1964, Bolan met his first manager, Geoffrey Delaroy-Hall, and recorded a slick commercial track backed by session musicians called "All at Once" (a song very much in the style of his youthful hero, Cliff Richard, the "English Elvis"), which was later released posthumously by Danielz and Caron Willans in 2008 as a very limited edition seven-inch vinyl after the original tape recording was passed on to them by Delaroy-Hall. This track is one of Bolan's first professional recordings.

Bolan then changed his stage name to Toby Tyler when he met and moved in with child actor Allan Warren, who became his second manager. This encounter afforded Bolan a lifeline to the heart of show business, as Warren saw Bolan's potential while he spent hours sitting cross-legged on Warren's floor playing his acoustic guitar. Bolan at this time liked to appear wearing a corduroy peaked cap similar to his then-current source of inspiration, Bob Dylan. A series of photographs was commissioned with photographer Michael McGrath, although he recalls that Bolan "left no impression" on him at the time.[14] Warren also hired a recording studio and had Bolan's first acetates cut. Two tracks were later released; the Bob Dylan song "Blowin' in the Wind" and Dion's "The Road I'm On (Gloria)". A version of Betty Everett's "You're No Good" (still unreleased) was later submitted to EMI as an audition tape, but was turned down.

Warren later sold Bolan's contract and recordings for £200 to his landlord, property mogul David Kirch, in lieu of three months' back rent, but Kirch was too busy with his property empire to do anything for him. A year or so later, Bolan's mother pushed into Kirch's office and shouted at him that he had done nothing for her son. She demanded he tear up the contract and he willingly complied.[15][16][17] The tapes of the first two tracks produced during the Toby Tyler recording session vanished for over 25 years before resurfacing in 1991 and selling for nearly $8,000. Their eventual release on CD in 1993 made available some of the earliest of Bolan's known recordings.

He signed to Decca Records in August 1965. At this point his name changed to Marc Bolan via Marc Bowland. There are several accounts of why Bolan was chosen, including that it was derived from James Bolam, that it was a contraction of Bob Dylan, and – according to Bolan himself – that Decca Records chose the name.[18] He recorded his debut single "The Wizard" with the Ladybirds on backing vocals (later finding fame with Benny Hill), and studio session musicians playing all the instruments. "The Wizard", Bolan's first single, was released on 19 November 1965. It featured Jimmy Page and Big Jim Sullivan, was produced by Jim Economides, with music director Mike Leander. Two solo acoustic demos recorded shortly afterwards by the same team ("Reality" and "Song for a Soldier") have still only been given a limited official release in 2015 on seven-inch vinyl. Both songs are in a folk style reminiscent of Dylan and Donovan. A third song, "That's the Bag I'm In", written by New York folk singer and Dylan contemporary Fred Neil, was also committed to tape, but has not yet been released. In June 1966, a second official single was also released, with session-musician accompaniment, "The Third Degree", backed by "San Francisco Poet", Bolan's paean to the beat poets. Neither song made the charts.[9]

In 1966, Bolan turned up at Simon Napier-Bell's front door with his guitar and proclaimed that he was going to be a big star and he needed someone to make all of the arrangements. Napier-Bell invited Bolan in and listened to his songs. A recording session was immediately booked and the songs were very simply recorded (most of them were not actually released until 1974, on the album The Beginning of Doves). Only "Hippy Gumbo", a sinister-sounding, baroque folk-song, was released at the time as Bolan's third unsuccessful single. One song, "You Scare Me to Death", was used in a toothpaste advertisement. Some of the songs also resurfaced in 1982, with additional instrumentation added, on the album You Scare Me to Death. Napier-Bell managed the Yardbirds and John's Children and was at first going to slot Bolan into the Yardbirds. In early 1967, he eventually settled instead for John's Children because they needed a songwriter and he admired Bolan's writing ability. The band achieved some success as a live act but sold few records. A John's Children single written by Bolan called "Desdemona" was banned by the BBC for its line "lift up your skirt and fly".

His tenure with the band was brief. Following an ill-fated German tour with the Who, Bolan took some time to reassess his situation. Bolan's imagination was filled with new ideas and he began to write fantasy novels (The Krakenmist and Pictures Of Purple People) as well as poems and songs, sometimes finding it hard to separate facts from his own elaborate myth – he famously claimed to have spent time with a wizard in Paris who gave him secret knowledge and could levitate. The time spent with him was often alluded to but remained "mythical". In reality the wizard was probably American actor Riggs O'Hara with whom Bolan made a trip to Paris in 1965. Given time to reinvent himself, after John's Children, Bolan's songwriting took off and he began writing many of the poetic and neo-romantic songs that appeared on his first albums with T. Rex.[9]

1967–1970: Tyrannosaurus Rex

[edit]Bolan left John's Children when, among other problems, the band's equipment had been repossessed by their label Track Records. Unperturbed, he rallied to create Tyrannosaurus Rex, his own rock band together with guitarist Ben Cartland, drummer Steve Peregrin Took and an unknown bass player. Napier-Bell recalled of Bolan: "He got a gig at the Electric Garden then put an ad in Melody Maker to get the musicians. The paper came out on Wednesday, the day of the gig. At three o'clock he was interviewing musicians, at five he was getting ready to go on stage.... It was a disaster. He just got booed off the stage."[9] Following this concert, Bolan pared the band down to just himself and Took, and they continued as a psychedelic-folk rock acoustic duo, playing Bolan's songs, with Took playing assorted hand and kit percussion and occasional bass to Bolan's acoustic guitars and voice. Napier-Bell said of Bolan that after the first disastrous electric gig: "He didn't have the courage to try it again; it really had been a blow to his ego... Later he told everyone he'd been forced into going acoustic because Track Records had repossessed all his gear. In fact he'd been forced to go acoustic because he was scared to do anything else."[9]

The original version of Tyrannosaurus Rex with Took released three albums; two reached the top fifteen in the UK Albums Chart. They also had a top 40 hit "Debora" in 1968. They were supported with airplay by BBC Radio 1 DJ John Peel.[19] One of the highlights of this era was when the duo played at the first free Hyde Park concert in 1968. Although the free-spirited, drug-taking Took was fired from the group after their first American tour, they were a force within the hippie underground scene while they lasted. Their music was filled with Bolan's otherworldly poetry. In 1969, Bolan published his first and only book of poetry entitled The Warlock of Love. Although some critics dismissed it as self-indulgence, it was full of Bolan's florid prose and wordplay, selling 40,000 copies and in 1969–70 became one of Britain's best-selling books of poetry.[20] It was reprinted in 1992 by the Tyrannosaurus Rex Appreciation Society.[21]

In keeping with his early rock and roll interests, Bolan began bringing amplified guitar lines into the duo's music, buying a white Fender Stratocaster decorated with a paisley teardrop motif from Syd Barrett. After replacing Took with Mickey Finn, he let the electric influences come forward even further on A Beard of Stars, the final album to be credited to Tyrannosaurus Rex. It closed with the song "Elemental Child", featuring a long electric guitar break influenced by Jimi Hendrix.[9]

In September of 1970, the new line up of Tyrannosaurus Rex became headliners at the first Glastonbury Festival after The Kinks pulled out at the last minute. Co-creator of the festival, Michael Eavis, was close to cancelling the concert when he heard that Tyrannosaurus Rex would be playing a gig at Butlin's in Minehead that weekend. Despite Bolan agreeing for his group to replace The Kinks as headliners, and their sunset gig later being described as an inspiration for Glastonbury, Eavis could not afford to pay them at the time. He ultimately made and fulfilled an agreement to pay the group £100 per month, over a 5-month period, from profits made selling cow's milk.[22]

1971–1975: T. Rex, glam rock and other styles

[edit]Marc Bolan, the pixie prince of glam rock, remains a huge influence in music and fashion.

Becoming more adventurous musically, Bolan bought a modified vintage Gibson Les Paul guitar (featured on the cover of the album T. Rex), and then wrote and recorded his first hit "Ride a White Swan", which was dominated by a rolling hand-clapping back-beat, Bolan's electric guitar and Finn's percussion. At this time he also shortened the group's name to T. Rex.[9] Bolan and his producer Tony Visconti oversaw the session for "Ride a White Swan", the single that changed Bolan's career which was inspired in part by Mungo Jerry's success with "In the Summertime", moving Bolan away from predominantly acoustic numbers to a more electric sound.[24] Recorded on 1 July 1970 and released later that year, it made slow progress in the UK Top 40, until it finally peaked in early 1971 at number two.[25] Inspired by his muse, June Child, Bolan developed a fascination with women's clothing, an unlikely characteristic for a British male rocker at the time.[26]

Bolan followed "Ride a White Swan" and T. Rex by expanding the group to a quartet with bassist Steve Currie and drummer Bill Legend, and cutting a five-minute single, "Hot Love", with a rollicking rhythm, string accents and an extended sing-along chorus inspired somewhat by "Hey Jude". Bolan performed "Hot Love" on the BBC television show Top of the Pops wearing glitter on his face: the performance was later recognized as the foundation of glam rock.[4][27] For the viewers, it was a defining moment: "Bolan was magical, but also sexually heightened and androgynous".[4] The song was number one in the UK Singles Chart for six weeks and was quickly followed by "Get It On", a grittier, more adult tune that spent four weeks in the top spot.[25] The song, re-titled "Bang a Gong (Get It On)" when released in the US, reached No. 10 in the Billboard Hot 100 in early 1972.[4]

Dressed in a satin sailor suit, but also – and most importantly – with the glittery gold teardrops beneath his eyes. This performance is often acknowledged as the birth of glam. His androgynous style has been an enduring influence on fashion. From Gucci to Saint Laurent, fashion has long drawn inspiration from his style. He knew how to subvert gender norms into fantastical new shapes.

— Joobin Bekhrad, The Guardian, on Bolan's March 1971 appearance on Top of the Pops.[27]

In November 1971, the band's record label, Fly, released the Electric Warrior track "Jeepster" without Bolan's permission. Outraged, Bolan took advantage of the timely lapsing of his Fly Records contract and left for EMI, who gave him his own record label, the T. Rex Wax Co. Its bag and label featured a head-and-shoulders image of Bolan. Despite the lack of Bolan's endorsement, "Jeepster" peaked at number two in the UK Singles Chart.[28] Regarded as one of the band's best songs, Paste and Billboard ranked it number one and three on their lists of the top 10 T. Rex songs.[29][30]

In 1972, he achieved two more UK number ones with "Telegram Sam" and "Metal Guru" taken from The Slider, and two number twos in "Children of the Revolution" and "Solid Gold Easy Action".[25] In the same year he appeared in Born to Boogie, a documentary by Ringo Starr about T. Rex including a concert filmed at London's Wembley Empire Pool in March 1972. Mixed in were surreal scenes shot at John Lennon's mansion in Ascot and a session with T. Rex joined by Ringo Starr on a second drum kit and Elton John on piano. At this time T. Rex record sales accounted for about six per cent of total British domestic record sales. The band was reportedly selling 100,000 records a day; however, no T. Rex single ever became a million-seller in the UK, despite many gold discs and an average of four weeks at the top per number one hit. No T. Rex record was certified until 1985, as the record company had to pay for it, which Bolan's did not in the 1970s.[25]

Bolan took to wearing top hats and feather boas on stage as well as putting drops of glitter on each of his cheekbones. Stories are conflicting about his inspiration for this – some say it was introduced by his personal assistant, Chelita Secunda, although Bolan told John Pidgeon in a 1974 interview on Radio 1 that he noticed the glitter on his wife, June Child's dressing table prior to a photo session and casually daubed some on his face there and then. Other performers – and their fans – soon took up variations on the idea.

The glam era also saw the rise of Bolan's friend David Bowie, whom Bolan had come to know in the underground days (Bolan had played guitar on Bowie's 1970 single "Prettiest Star"; Bolan and Bowie also shared the same manager, Les Conn, and producer, Tony Visconti) but their friendship was also a rivalry, which continued throughout his career. Bowie's 1972 song "All the Young Dudes" name-checked T. Rex.[31] Bowie's song "Lady Stardust" is generally interpreted as alluding to fellow glam rock icon Bolan. The original demo version was entitled "He Was Alright (A Song for Marc)"[32]

In 1973, Bolan played twin lead guitar alongside his friend Jeff Lynne on the Electric Light Orchestra songs "Ma-Ma-Ma Belle" and "Dreaming of 4000" (originally uncredited) from On the Third Day, as well as on "Everyone's Born to Die", which was not released at the time but appears as a bonus track on the 2006 remaster.[25]

For the following recording sessions, he recruited soul female singers for the backing vocals on "20th Century Boy", which peaked at number 3 in March, and mid-year "The Groover" which went to number four.[25] Tanx, parts of which found him heading towards soul, funk and gospel, was both a commercial and critical success in several European countries. "Truck On (Tyke)" missed the UK top 10 reaching only No. 12 in December. However, "Teenage Dream" from the 1974 album Zinc Alloy and the Hidden Riders of Tomorrow showed that Bolan was attempting to create richer, more involved music than he had previously attempted with T. Rex. He expanded the line up of the band to include a second guitarist, Jack Green, and other studio musicians, and began to take more control over the sound and production of his records, including by then girlfriend Gloria Jones on keyboards as well as backing vocals.

Eventually, the vintage T. Rex line-up disintegrated. Bolan's marriage came to an end because of his affair with backing singer Jones, which began in July 1973. He spent a good deal of his time in the US during this period, continuing to release singles and albums, putting R & B influences with rock on Bolan's Zip Gun.

1976–1977: resurgence and final year

[edit]In September 1975, Gloria Jones gave birth to Bolan's son, whom they named Rolan Bolan (although his birth certificate lists him as 'Rolan Seymour Feld'). That same year, Bolan returned to the UK from tax exile in the US and Monaco and to the public eye with a low-key tour. Bolan made regular appearances on the LWT pop show Supersonic, directed by his old friend Mike Mansfield and released a succession of singles, including "New York City" which peaked at number 15. By then, Bolan was current with the music scene, incorporating disco elements in Futuristic Dragon and the single "Dreamy Lady". In June 1976, Bolan released "I Love to Boogie", which peaked at number 13. The last remaining member of Bolan's halcyon era T. Rex, Currie, left the group in late 1976. In early 1977, Bolan got a new band together, released a new album, Dandy in the Underworld, and set out on a fresh UK tour, taking along punk band the Damned as support to entice a young audience who did not remember his heyday barely five years previously.[9]

Later in 1977, Granada Television commissioned Bolan to front a six-part series called Marc in which he hosted a mix of new and established bands and performed his own songs. By this time Bolan had lost weight, appearing as trim as he had during T. Rex's earlier heyday. The show was broadcast during the post-school half-hour on ITV earmarked for children and teenagers and it was a big success. One episode reunited Bolan with his former John's Children bandmate Andy Ellison, then fronting the band Radio Stars.[9]

Bolan's longtime friend and sometimes rival David Bowie was the final guest on the last episode of Marc. Bowie's solo song "Heroes" was the show's penultimate song; Bolan signed off, naming some of the musicians: "All the cats; you know who they are"; they then began to play a bluesy song, over the closing credits. After four words of Bowie's vocals, however, Bolan stumbled forward, and off the stage, but managed to grab the microphone, and find a smile. Bowie's amusement was clearly visible, and the band stopped playing after a few seconds. With no time for a retake, the occurrence was aired.[33]

Personal life

[edit]Bolan began his first serious romantic relationship, with Teresa Whipman, in 1965.[34] They broke up in 1968 when Bolan met June Ellen Child. The pair immediately fell in love and moved into a flat together after knowing each other for only a few days.[35] They married on 30 January 1970.[36] She was a former secretary to his then managers, Blackhill Enterprises, also the managers of another of his heroes, Syd Barrett, who June had previously dated.[37] She was also influential in raising her new husband's profile in the music industry.[9] Bolan's relationship with June was tumultuous; he engaged in several affairs over the course of their marriage, including one with singer Marsha Hunt in 1969, and another with artist Barbara Nessim while recording in America in 1971.[38][39] The couple separated in 1973, after June found out about Bolan's affair with his backing singer Gloria Jones.[40] After Bolan's death, June revealed that she had abortions during their marriage because she believed Bolan was not mature enough to be a father.[41][42]

Bolan and Gloria Jones were in a committed romantic relationship from 1973 until his death in September 1977.[43] The couple had a son together in September 1975 and the three of them lived together for nearly two years until Bolan's death. At the end of June 1976, June Bolan sued for divorce on the grounds of adultery, citing Gloria Jones as the third party. At the court hearing on 5 October 1976, Deputy Judge Donald Ellison declared: "I am satisfied that the husband committed adultery with the co-respondent, and that the wife finds it intolerable to live with him"[citation needed] and granted a decree nisi. Twelve months after that date, it was to become a decree absolute, thus severing the Bolans' matrimonial ties. "The facts are that she initially left me, and we just grew apart", Bolan explained after the ruling. "There were no great scenes, no smashing things up. It just suddenly happened one day. We weren't a couple anymore." He also used the opportunity to shed a little light on his sexuality. "Anyway, I'm gay", he only half-jested. "I can't say I was a latent homosexual – I was an early one. But sex was never a great problem. I'm a great screwer." Asked about the institution of marriage, he replied: "Gloria doesn't want to get married and neither do I. If I ever marry anyone again, I'll put in a clause that when it ends you're on your own – and that means financially, too."[44] During an interview in 1975, Bolan was also asked about his sexuality, and said that he was bisexual.[45]

Bolan never learned to drive,[46][47] fearing he would die before reaching 30 years old.[48][49] Despite this fear, cars or automotive components are at least mentioned in, if not the subject of, many of his songs. He also owned a number of vehicles, including a white 1960s Rolls-Royce that was loaned by his management to the band Hawkwind on the night of his death.[50][51]

Death

[edit]On 16 September 1977, two weeks before his 30th birthday, Bolan was a passenger in a Mini 1275GT driven by Gloria Jones as they headed home from Morton's Club Restaurant in Berkeley Square, London. Both had been drinking alcohol, and after crossing a small humpback bridge near Gipsy Lane on Queens Ride, Barnes, south west London, the car struck a fence post and then a tree.[52][53][54] Bolan died at the scene. Jones was critically injured.[52][54]

The car crash site has become a shrine to his memory, where fans leave tributes beside the tree. In 2013, the shrine was featured on the BBC Four series Pagans and Pilgrims: Britain's Holiest Places.[55] The site, Marc Bolan's Rock Shrine, is owned and maintained by the T. Rex Action Group.[56]

His funeral service was held on 20 September 1977 at the Golders Green Crematorium in North London. Bolan's ashes were later buried under a rose bush. Bolan's funeral was attended by David Bowie, Rod Stewart, Tony Visconti, Steve Harley and Boy George among other musicians.[57][58] Bolan had arranged a discretionary trust to safeguard his money. A small, separate Jersey-based trust fund has allowed his son to receive some income. However, the bulk of Bolan's fortune, variously estimated at between £20 and £30 million (approx $38 – $57 million), remains in trust.[59]

Legacy

[edit]Bolan strongly influenced artists of many genres, including glam rock, punk, post-punk, new wave, indie rock, Britpop and alternative rock. After seeing Bolan wearing Zandra Rhodes-designed outfits, Freddie Mercury enlisted Rhodes to design costumes for the next Queen tour in 1974.[60] Bolan was the early guitar idol of Johnny Marr, who later found fame as the guitarist of the influential indie rock band the Smiths.[61] Emerging in the New Romantic movement in the early 1980s, Boy George spoke of the impact Bolan and Bowie had on him: "They represented a kind of bohemian existence that I – at that point – could only imagine living. I loved the music. The first time I ever saw Marc Bolan really, properly was singing 'Metal Guru' and just loved him. I don't think you can separate an artist from what they wear or what they sing – it's kind of the complete package."[62]

The T. Rex singer captivated generations with his strutting music and hyper-sexual charisma.

The 1973 album Still by former King Crimson lyricist Peter Sinfield mentions Bolan in the title track: "Beatles and Bolans, raindrops and oceans".[63] In 1980, the Bongos were the first American group, with "Mambo Sun", to enter the Billboard charts with a T. Rex cover. Since then, Bongos frontman Richard Barone has recorded several other Bolan compositions ("The Visit", "Ballrooms of Mars"), worked with T. Rex producer Tony Visconti for his 2010 solo album, Glow, that includes a remake of Bolan's "Girl" from Electric Warrior, and has himself produced tracks for Bolan's son Rolan.

In 1985, Duran Duran splinter band the Power Station, with Robert Palmer as vocalist, took a version of "Get It On" into the UK Top 40 and to US No. 6, the first cover of a Bolan song to enter the charts since his death. They also performed the tune (with Michael Des Barres replacing Palmer) at the Live Aid concert. In 1986, Violent Femmes covered the song "Children of the Revolution" on their album, The Blind Leading the Naked.[64] In 1991, Japanese rock band T-Bolan were named after T. Rex and Bolan.[65]

It felt like he actually cast a spell. I've no doubt every aspect of how he presented himself was just an outpouring of his understanding that things could be magical, things could be heightened. Out in the ordinary world, he managed to cast a spell over all of us.

"20th Century Boy" introduced a new generation of devotees to Bolan's work in 1991 when it was featured on a Levi's jeans TV commercial featuring Brad Pitt,[66] and was re-released, reaching No. 13 in the UK.[67] The song was performed by the fictional band the Flaming Creatures (performed by Placebo, reprised by Placebo and David Bowie at the 1999 Brit Awards) in the 1998 film Velvet Goldmine. In every decade since his death, a Bolan greatest hits compilation has placed in the top 20 UK albums and periodic boosts in sales have come via cover versions from artists inspired by Bolan, including Morrissey. In 1991, Morrissey and David Bowie performed a duet of "Cosmic Dancer" at the Inglewood Forum in Los Angeles.[68]

The Cameron Crowe-created movie Almost Famous features a scene in which a Black Sabbath groupie is telling aspiring journalist William Miller about how "Marc Bolan broke her heart, man. It's famous", regarding the character of Penny Lane, played by Kate Hudson.[69] In 2000, Naoki Urasawa created a Japanese manga entitled 20th Century Boys that was inspired by Marc Bolan's song "20th Century Boy". The series is a multiple award-winner, and has also been released in North America. The story was adopted into three successful live-action movies from 2008 to 2009, which were also released in the US, Canada and the UK.[70]

In 2020, Kesha recorded a cover of "Children of the Revolution" along with Bolan's son Rolan on backing vocals.[71]

In 2007, the English Tourist Board included Bolan's Rock Shrine in their guide to Important Sites of Rock 'n Roll interest 'England Rocks'.[72] As reported in 2011, a school is planned in his honour, to be built in Sierra Leone: The Marc Bolan School of Music and Film.[73] A musical, 20th Century Boy, based on Bolan's life, and featuring his music, premiered at the New Wolsey Theatre in Ipswich in 2011.[74]

In September 2020, a tribute album produced by Hal Willner, Angelheaded Hipster, was released featuring covers of Bolan songs by a variety of artists including Nick Cave, U2, Elton John, Joan Jett, Nena and Todd Rundgren.[75] Two months later, Bolan and T. Rex bandmates Steve Currie, Mickey Finn and Bill Legend were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as part of the class of 2020 by Beatles drummer Ringo Starr.[76]

In September 2025, an English Heritage blue plaque was unveiled on the site of Bolan's home in Maida Vale, west London, where he had lived from 1970 to 1972. The unveiling ceremony was attended by the Damned's Rat Scabies and Captain Sensible, Primal Scream's Bobby Gillespie, and Rick Wakeman from the band Yes.[77][78]

Discography

[edit]See T. Rex discography for full details of releases by Tyrannosaurus Rex and T. Rex. Solo releases and other releases are listed below.

Albums

[edit]with John's Children

- The Legendary Orgasm Album (1982)

- Smashed Blocked! (1997)

as Marc Bolan

- The Beginning of Doves (1974)

- You Scare Me to Death (1981)

- Dance in the Midnight (1983)

- Observations (1992)

with Tyrannosaurus Rex

- My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair... But Now They're Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows (1968)

- Prophets, Seers & Sages: The Angels of the Ages (1968)

- Unicorn (1969)

- A Beard of Stars (1970)

with T. Rex

- T. Rex (1970)

- Electric Warrior (1971)

- The Slider (1972)

- Tanx (1973)

- Zinc Alloy and the Hidden Riders of Tomorrow (1974)

- Bolan's Zip Gun (1975)

- Futuristic Dragon (1976)

- Dandy in the Underworld (1977)

- Billy Super Duper (1982)

Singles

[edit]as Marc Bolan

- 1965 "The Wizard / Beyond the Rising Sun"

- 1966 "The Third Degree / San Francisco Poet"

- 1967 "Hippy Gumbo / Misfit"

with John's Children

- 1967 "Desdemona / Remember Thomas A Beckett"

with Tyrannosaurus Rex

- 1968 "Debora / Child Star"

- 1968 "One Inch Rock / Salamanda Palaganda"

- 1969 "Pewter Suitor/Warlord of the Royal Crocodiles"

- 1969 "King of the Rumbling Spires / Do You Remember"

- 1970 "By the Light of a Magical Moon / Find a Little Wood"

T. Rex

- 1970 "Ride a White Swan / Is It Love / Summertime Blues"

- 1971 "Hot Love / The King of the Mountain Cometh / Woodland Rock"

- 1971 "Get It On (Bang a Gong) / Raw Ramp"

- 1971 "Jeepster / Life's a Gas"

- 1972 "Telegram Sam / Cadilac / Baby Strange"

- 1972 "Metal Guru / Thunderwing / Lady"

- 1972 "The Slider / Chariot Choogle" (not officially released, however, some copies exist)

- 1972 "Debora / One Inch Rock / Woodland Bop / The Seal of Seasons" (re-issued)(MagniFly EP)"

- 1972 "Children of the Revolution / Jitterbug Love / Sunken Rags"

- 1972 "Solid Gold Easy Action / Born to Boogie"

- 1973 "20th Century Boy / Free Angel"

- 1973 "The Groover / Midnight"

- 1973 "Truck On (Tyke) / Sitting Here"

- 1973 "Blackjack / Squint Eye Mangle" as Big Carrot

- 1974 "Teenage Dream / Satisfaction Pony"

- 1974 "Light of Love / Explosive Mouth"

- 1974 "Zip Gun Boogie / Space Boss"

- 1975 "New York City / Chrome Sitar"

- 1975 "Dreamy Lady / Do You Wanna Dance/Dock of the Bay"

- 1975 "Christmas Bop / Telegram Sam / Metal Guru" (not released, however, some paper labels exist)

- 1976 "London Boys / Solid Baby"

- 1976 "I Love to Boogie / Baby Boomerang"

- 1976 "Laser Love / Life's An Elevator"

- 1977 "The Soul of My Suit / All Alone"

- 1977 "Dandy in the Underworld / Groove a Little / Tame My Tiger"

- 1977 "To Know You Is to Love You / City Port"

- 1977 "Celebrate Summer / Ride My Wheels"

- 1977 "Ride a White Swan / The Motivator / Jeepster / Demon Queen"

- 1977 "Get It On / Hot Love" (re-issued)

- 1978 "Hot Love / Raw Ramp / Lean Woman Blues"

- 1978 "Crimson Moon / Jason B. Sad"

- 1978 "You Scare Me to Death / The Perfumed Garden of Gulliver Smith"

References

[edit]- ^ Peraino, Judith (31 December 2006). Listening to the Sirens: Musical Technologies of Queer Identity from Homer to Hedwig. University of California Press. p. 229. ISBN 9780520215870 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Class of 2020". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "Tony Visconti: 'What I saw in Marc Bolan was raw talent. I saw genius'. The Guardian. Retrieved 3 February 2019

- ^ a b c d e f Petridis, Alex (4 September 2020). "Why Marc Bolan was 'the perfect pop star', by Elton John, U2 and more". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Barnes, Ken (March 1978). "The Glitter Era: Teenage Rampage". Bomp!. Retrieved 26 January 2019 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "Electric Warrior – T. Rex". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ "Paul Du Noyer on Marc Bolan of T.Rex". Pauldunoyer.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ De Lisle, Tim (17 August 1997). "Solid gold, easy action". The Independent. London. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Thompson, Dave (2007). T-Rex— Up Close And Personal.

- ^ Bramley, John & Shan (1992). Marc Bolan: The Legendary Years. London: Smith Gryphon Publishers. pp. 13–14. ISBN 1-85685-138-9.

- ^ "'He got expelled for nutting the teacher': Friends of glam rock icon Marc Bolan look back on 40th anniversary of his death". Hackney Gazette. Retrieved 30 November 2023

- ^ Johnson, David (22 October 2015). "Obituaries: Angus McGill". The Independent. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ "McG could write about what he enjoyed". 47 Shoe Lane. 2 November 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Paytress, Mark (2006). Bolan: The Rise and Fall of a 20th Century Superstar. Omnibus Press. ISBN 1-84609-147-0.

- ^ Warren, Allan (1976). The confessions of a society photographer. London: Jupiter. ISBN 978-0-904041-68-2.

- ^ Warren, Allan (1999). Dukes, Queens and Other Stories. London: New Millennium Books.

- ^ "Marc Bolan—The Early Years". Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ Paytress, Mark (5 November 2009). Marc Bolan: The Rise And Fall Of A 20th Century Superstar. Omnibus Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780857120236.

- ^ "Stand and Deliver: The Autobiography". p. 122. Pan Macmillan, 2007

- ^ "Bolan and Keats". Keatsian.co.uk. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "Reprinted 'The Warlock of Love' by Marc Bolan". Connectedglobe.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Retter, Emily (20 June 2020). "'We made a loss on first Glastonbury despite paying Marc Bolan with milk money'". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 4 August 2025.

- ^ Sweeting, Adam. "Marc Bolan: Why the prettiest star still shines". The Telegraph. 30 August 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ Philip Auslander Performing glam rock: gender and theatricality in popular music University of Michigan Press, 2006

- ^ a b c d e f "T. Rex UK charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "MARC BOLAN: A Legendary Rock Star Glimmering A Shine To Modern Music Trends Today". FIB. 26 January 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Glitter and curls: Marc Bolan and the birth of glam rock style". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "T. Rex |Artist| Official Charts". Official Charts. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Lynch, Joe (5 November 2020). "T. Rex's 10 Best Songs: Staff Picks". Billboard. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Manno, Lizzie (14 December 2018). "Top 10 Best T. Rex Songs". Paste. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Roy Carr & Charles Shaar Murray (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record: p.117

- ^ David Buckley (1999). Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story: pp.146–7

- ^ "Mark Bolan falls off stage on 'Marc' Show 6, 1977 via YouTube". Retrieved 7 October 2011 – via YouTube.

- ^ Paytress, Mark. Bolan: The Rise and Fall of a 20th Century Superstar. Omnibus Press, 2009. p.53. ISBN 9780857120236

- ^ Welch, Chris, Bell, Simon Napier. Marc Bolan: Born to Boogie. Plexus Publishing, 2008. p.62. ISBN 978-0859654111

- ^ "My Daddy of Britpop by Marc Bolan's son". Evening Standard. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Mabbett, Andy (2010). Pink Floyd - The Music and the Mystery. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

- ^ Jones, Lesley-Ann. Ride a White Swan: The Lives and Death of Marc Bolan. Hodder & Stoughton, 2012. p. 157. ISBN 978-1444758771

- ^ Jones, Lesley-Ann. Ride a White Swan: The Lives and Death of Marc Bolan. Hodder & Stoughton, 2012. p.209. ISBN 978-1444758771

- ^ Jones, Lesley-Ann. Ride a White Swan: The Lives and Death of Marc Bolan. Hodder & Stoughton, 2012. p. 347. ISBN 978-1444758771

- ^ Jones, Lesley-Ann. Ride a White Swan: The Lives and Death of Marc Bolan. Hodder & Stoughton, 2012. p.362. ISBN 978-1444758771

- ^ Brook, Danae (13 March 1978). "My Baby will bring Marc back to me". Evening Standard.

- ^ Jones, Lesley-Ann. Ride a White Swan: The Lives and Death of Marc Bolan. Hodder & Stoughton, 2012. p. 348. ISBN 978-1444758771

- ^ Paytress, Mark. Bolan: The Rise and Fall of a 20th Century Superstar. Omnibus Press, 2009. p.318. ISBN 9780857120236

- ^ Iles, Jan (1 February 1975). "Whatever Happened to the Teenage Dream?". Record and Popswop Mirror. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Hebblethwaite, Phil (15 September 2017). "40 years on: 6 things you possibly didn't know about Marc Bolan". BBC.

- ^ Brown, Mick. "Behind the glitter". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Roland, Paul (2012). Cosmic Dancer:The Life & Music of Marc Bolan. Tomahawk Press. ISBN 978-0956683403.

- ^ "How T. Rex Legend Marc Bolan Predicted His Own Death In a Song; Professor of Rock Investigates (Video)". BraveWords. 22 April 2022.

- ^ Napier-Bell, Simon (2002). Black Vinyl, White Powder. London: Ebury Press. p. 177.

- ^ Paytress, Mark (2009). Bolan: Rise and Fall of a 20th Century Superstar. London: Omnibus Press.

- ^ a b Bignell, Paul (16 September 2012). "Mystery of Marc Bolan's death solved". The Independent. London. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ "Marc Bolan's Rock Shrine Site". Marc-Bolan.net. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ a b Pryce, Mike (22 September 2013). "The night I cut Marc Bolan from the wreckage of his car". Worcester News. Newsquest. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Pagans and Pilgrims: Britain's Holiest Places". BBC. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ "The Homegrown T. Rex Memorial". Slate. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "T. Rex Guitarist Marc Bolan Dies in Car Accident". Rolling Stone. 3 November 1977. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ "Boy George Talks T Rex 1987 • Mister Mister Marc Bolan Radio 1". 2 August 2017 – via Youtube.

- ^ "The truth about Marc Bolan's Herefordshire home". Gloucestershire Echo. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Blake, Mark (2010). Is This the Real Life?: The Untold Story of Queen. Aurum.

- ^ "Johnny Marr biography". Official Johnny Marr website. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ Murray, Robin (30 October 2013), "Boy George: How To Make A Pop Idol", Clash, archived from the original on 20 December 2015, retrieved 30 June 2022

- ^ "Still". www.songsouponsea.com. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ Woodstra, Chris. "Violent Femmes – The Blind Leading the Naked". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ "亀田大毅が歌ったT-Bolanのルーツ! T.Rexの無料映像を配信!" (in Japanese). Barks. 8 June 2006. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ The Oxford Handbook of Music and Advertising. Oxford University Press. 2021. p. 457.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ "David Bowie and Morrissey covering T-Rex's Cosmic Dancer is pure joy". Radio X. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ "T. Rex's Marc Bolan, always famous – and flamboyant". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 February 2019

- ^ "Official Website for Naoki Urasawa's 20th Century Boys". Viz Media. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Marc Bolan's son Rolan sings on new version of T Rex classic 'Children of the Revolution' with Kesha". Gold Radio. 24 June 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "Rockin' all over England". The Daily Telegraph. 3 February 2007. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "Marc Bolan School Of Music And Film opens in Sierra Leone". NME. 2 August 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ "A Show About Bolan in Ipswich". WhatsOnStage.com. 24 May 2011. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "Nick Cave Covers T. Rex's 'Cosmic Dancer' for New Tribute Album 'Angelheaded Hipster'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "T. Rex | Rock & Roll Hall of Fame". www.rockhall.com. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "T. Rex star Marc Bolan gets blue plaque at former Maida Vale home". BBC News. 30 September 2025. Retrieved 1 October 2025.

- ^ Harteam Moore, Sam (30 September 2025). "Marc Bolan honoured with blue plaque in London". PRS for Music. Retrieved 1 October 2025.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bolan, Marc. The Warlock Of Love, Lupus Publishing: 1969.

- Tremlett, George. The Marc Bolan Story, Futura: 1975, ISBN 9780860070689

- Willans, Caron & John - ‘Wilderness of the Mind - Marc Bolan’ Xanadu Publications 1991

- Sinclair, Paul. Electric Warrior: The Marc Bolan Story, Omnibus Press: 1982, ISBN 978-0711900547

- Du Noyer, Paul. Marc Bolan: Virgin Modern Icons, Virgin Books: 1997, ISBN 978-1852276836

- McLenehan, Cliff. Marc Bolan: A Chronology 1947-1977, Helter Skelter Publishing: 2002, ISBN 978-1900924429

- Paytress, Mark. Bolan: The Rise and Fall of a 20th Century Superstar, Omnibus Press: 2003, ISBN 978-1846091476

- Ewens, Carl. Born To Boogie: The Songwriting Of Marc Bolan, Aureus Publishing: 2007, ISBN 978-1899750399

- Roland, Paul. Cosmic Dancer: The Life & Music of Marc Bolan. Tomahawk Press. 2012, ISBN 978-0956683403

- Jones, Lesley-Ann. Ride a White Swan: The Lives and Death of Marc Bolan. Hodder 2013, ISBN 978-1444758795

- Bramley, John. Marc Bolan: Beautiful Dreamer. John Blake Publishing Ltd. 2017, ISBN 978-1786064486

External links

[edit]Marc Bolan

View on GrokipediaEarly life

Birth and family

Marc Bolan was born Mark Feld on 30 September 1947 at Hackney General Hospital in east London.[7][8] He grew up in the working-class neighborhood of Stoke Newington, within the Hackney borough, at 25 Stoke Newington Common, during the post-war austerity period.[7][2] His father, Simeon "Sid" Feld, was a lorry driver of Ashkenazi Jewish descent with roots in Russia and Poland, while his mother, Phyllis Winifred (née Atkins), was English and worked on a fruit stall.[8][9] The family observed Jewish traditions to some extent, reflecting the father's heritage, though Phyllis came from a Christian background.[8] Marc had an older brother, Harry Feld, with whom he shared a close but sometimes competitive sibling dynamic in their modest home.[7][2] The Felds relocated from Hackney to Wimbledon in southwest London around 1962, when Mark was about 15, likely due to council rehousing amid urban changes.[7] This series of moves shaped a formative environment of modest stability in post-war Britain. Bolan's initial exposure to music came early in the family home, where he encountered rock 'n' roll through records like Bill Haley's "Rock Around the Clock," sparking his lifelong passion.[7] At age nine, his mother purchased a Suzuki acoustic guitar for him on hire purchase and he formed a skiffle band with school friends, laying the groundwork for his adolescent immersion in rock influences such as Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran.[8][7][10]Early influences and education

Bolan attended Northwold Primary School in Stoke Newington, where he formed his first skiffle band, Susie and the Hula Hoops—which included future singer Helen Shapiro as vocalist—at the age of nine.[7] Later, he moved to William Wordsworth Secondary Modern School in Stoke Newington, starting in 1958 at age 11, where he showed an early interest in history and the arts but struggled with formal education.[10] Around age 15, he was expelled from the school after refusing corporal punishment—the cane—from the deputy headmaster, Mr. Pearson, and headbutting him in defiance, an incident that highlighted his growing rebellious nature.[11] His early artistic pursuits were shaped by a fascination with bohemian culture, leading him to explore poetry, writing verses that drew criticism from teachers who dismissed his potential.[11] Influenced by literary figures such as Shakespeare, Rimbaud, and Bob Dylan, Bolan immersed himself in poetry books, which ignited his creative ambitions; reading Rimbaud, in particular, inspired him to pen his own works.[12] He also dabbled in painting and showed an affinity for visual arts, reflecting a broader bohemian ethos that extended to modeling, where at age 15 he joined an agency and appeared in magazines like Town as an exemplar of Mod style.[7] Musically, Bolan's father introduced him to rock 'n' roll through records like Bill Haley's Rock Around the Clock, fostering a lifelong passion that evolved into admiration for Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan.[7] At age nine, his mother purchased a Suzuki acoustic guitar for him on hire purchase, which he taught himself to play, often performing during school lunch breaks to small groups of friends.[10] These early experiences, supported by his family's encouragement of his musical interests despite his academic disinterest, laid the foundation for his artistic development before entering professional pursuits.[11]Music career

1964–1967: Initial recordings and bands

In 1964, at the age of 17, Mark Feld adopted the stage name Toby Tyler—inspired by a children's novel and film—and transitioned into modeling to support his ambitions in entertainment. He appeared in fashion features, including a spread in Town magazine that highlighted him as an exemplar of the mod subculture, with his sharp suits and styled hair capturing the era's youthful, stylish ethos. This period marked his entry into London's creative scene, where modeling provided connections and visibility while he pursued music on the side.[13] Bolan's first musical release came in November 1965 with the single "The Wizard" b/w "Beyond the Risin' Sun" on Decca Records, a folk-tinged track produced by Les Vandyke and featuring session players like Jimmy Page on guitar and Big Jim Sullivan on sitar. Issued under the Toby Tyler moniker, it drew from Bolan's early acoustic influences but failed to chart, though it earned modest reviews for its poetic lyrics and exotic arrangement. The following year, he reverted to his birth surname for recordings and signed with influential producer-manager Simon Napier-Bell, who had previously worked with the Yardbirds. Under Napier-Bell's guidance, Bolan cut whimsical, proto-psychedelic demos and released the single "Hippy Gumbo" b/w "Misfit" on Parlophone Records in January 1967, adopting a pixie-like persona in the process; the A-side's bouncy folk melody and Bolan's high-pitched vocals hinted at his emerging eccentricity, but it too sank without commercial impact.[14][15][16][17] Amid these solo efforts, Bolan immersed himself in the mod and emerging psychedelic scenes, briefly joining short-lived groups that experimented with R&B and pop covers. In late 1966, he became guitarist and co-vocalist for John's Children, a volatile mod-proto-punk band managed by Napier-Bell. During his six-month stint through early 1967, Bolan co-wrote and performed on several tracks, most notably "Desdemona," released as a single in May 1967 on Track Records with lyrics like "Lift up your skirt and fly" that prompted a BBC ban for perceived indecency (later edited to "Why don't you come and play with me"). The song's raw energy and Bolan's fuzzy guitar work foreshadowed his later style, though internal band tensions led to his departure by spring 1967.[18]1967–1970: Tyrannosaurus Rex formation and acoustic phase

In 1967, following his brief stint with John's Children, Marc Bolan placed an advertisement seeking a percussionist, leading to his meeting with seventeen-year-old Steve Peregrin Took, a fellow musician influenced by the emerging London underground scene.[19] The pair quickly formed the acoustic folk duo Tyrannosaurus Rex, characterized by Bolan's poetic, mythological lyrics delivered over gentle guitar fingerpicking and Took's intricate bongo and hand-percussion rhythms.[20] This minimalist setup aligned with the era's hippie ethos, emphasizing improvisation and intimacy over amplification. Tyrannosaurus Rex gained early visibility through performances at key underground venues like the UFO Club in London's Soho, where producer Tony Visconti first spotted them in late 1967.[21] Impressed by their ethereal sound, Visconti signed the duo to EMI's Regal Zonophone label in early 1968, taking on production duties himself.[20] Their debut single, "Debora," released on April 19, 1968, captured this acoustic purity with Bolan's whimsical vocals and a simple guitar-bongo arrangement, peaking at number 34 on the UK Singles Chart.[22] The track's modest success helped secure a cult audience among London's hippie counterculture, drawn to its otherworldly charm. The duo's debut album, My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair... But Now They're Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows, followed on July 5, 1968, recorded at Advision Studios under Visconti's guidance.[23] Featuring 13 short, vignette-like songs steeped in fantasy and folklore, the record exemplified their acoustic folk style, with tracks like "Hot Rod Mama" showcasing Bolan's rapid-fire guitar and Took's subtle percussion.[24] Bolstered by radio support from BBC DJ John Peel, who narrated a story on the album, it resonated in the underground, though commercial sales remained niche.[25] Live shows further solidified their hippie following, with appearances at free festivals such as the inaugural Hyde Park concert on June 29, 1968, alongside acts like Pink Floyd and Jethro Tull, and the Woburn Music Festival in July of that year.[26] These outdoor events, emblematic of the era's communal spirit, drew crowds of freaks and flower children who embraced the duo's mystical, unplugged performances at spots like the Middle Earth club, their official live debut venue on September 23, 1967.[27] By late 1968, Tyrannosaurus Rex had cultivated a dedicated underground fanbase, often performing seated on stage to enhance the intimate, trance-like atmosphere. Their second album, Prophets, Seers & Sages: The Angels of the Ages, arrived on October 14, 1968, comprising even briefer acoustic sketches that revisited "Debora" in a reversed-tape variant titled "Deboraarobed."[28] Recorded swiftly between May and August at Trident Studios, it maintained the duo's esoteric focus but hinted at growing creative frictions, as Bolan increasingly dominated songwriting. The release reinforced their status in the psychedelic folk niche, appealing to listeners seeking escapist, myth-laden soundscapes amid the late-1960s cultural upheaval. Tensions escalated during sessions for the third album, Unicorn, released on May 16, 1969, which introduced subtle electric elements like bass guitar while retaining the core acoustic duo dynamic.[29] Produced by Visconti at Trident, the record's more structured songs, such as "Childe" and "Romany Soup," reflected Bolan's evolving ambitions, but underlying disputes over creative control and lifestyle differences—exacerbated by Took's onstage antics and drug use during a troubled U.S. tour in late 1969—culminated in Bolan's dismissal of Took in September 1969.[19] Seeking a fresh partner, Bolan recruited percussionist Mickey Finn later that year, marking the acoustic phase's end and paving the way for an electric transformation by 1970.[20]1970–1972: T. Rex electric shift and breakthrough

In 1970, Marc Bolan rebranded his band from the folk-oriented Tyrannosaurus Rex to the punchier T. Rex, signaling a deliberate pivot toward electric instrumentation and a more commercial rock sound that built upon his acoustic roots.[30] To facilitate live performances of this evolving style, Bolan assembled a fuller lineup by adding bassist Steve Currie and drummer Bill Legend, moving beyond the duo format with percussionist Mickey Finn.[31] This reconfiguration allowed T. Rex to deliver the amplified energy central to Bolan's vision of glam-infused rock. The transition yielded immediate results with the non-album single "Ride a White Swan," released in October 1970, which captured Bolan's whimsical lyrics over a driving electric riff and propelled the band into the UK Top 10, peaking at number 2.[32] The self-titled album T. Rex, issued in December 1970, further solidified this shift by compiling recent singles and introducing a polished, boogie-inflected sound that contrasted the band's earlier obscurity.[33] The pinnacle of this breakthrough came with Electric Warrior, released in September 1971 and produced by longtime collaborator Tony Visconti, whose arrangements emphasized Bolan's charismatic vocals and guitar work alongside contributions from session musicians like Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman on backing vocals.[34] Standout tracks "Get It On" and "Jeepster" dominated the UK charts, with the former reaching number 1 and the latter number 2, fueling the "T. Rextasy" phenomenon—a teenybopper frenzy of screaming young fans that echoed Beatlemania and was amplified by Bolan's frequent, captivating appearances on Top of the Pops.[35] To meet the surging demand for tours, T. Rex formalized its expanded ensemble, incorporating Kaylan and Volman (no relation to Bolan, born Mark Feld) as key vocal supports.[36] This domestic explosion extended abroad, as "Bang a Gong (Get It On)"—the U.S. retitling of "Get It On"—climbed to number 10 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1972, establishing T. Rex's international foothold and cementing Bolan's status as a glam rock icon.[37]1973–1977: Glam peak, experimentation, and final works

In 1973, T. Rex reached the zenith of their glam rock popularity with the release of Tanx on March 16, which marked a departure from the band's earlier sound by incorporating soul, funk, and gospel elements, influenced by Bolan's relationship with singer Gloria Jones.[38][39] The album featured female backing vocals and mellotron, blending these with the group's signature boogie rhythms, as heard in tracks like "Tenement Lady" and "Broken-Hearted Blues."[40] Despite critical mixed reception for its experimental shifts, Tanx achieved commercial success, peaking at No. 4 on the UK Albums Chart.[41] Key singles from this era included "20th Century Boy," which reached No. 3 on the UK Singles Chart in April 1973, and "Children of the Revolution," a No. 2 hit from late 1972 that carried over into the album's promotional cycle, solidifying T. Rex's status as glam icons.[42] The following year, Bolan pushed further into experimentation with Zinc Alloy and the Hidden Riders of Tomorrow, released on February 1, 1974, under the expanded moniker Marc Bolan & T. Rex, exploring R&B grooves and sci-fi-themed lyrics inspired by Bolan's interest in futuristic narratives and American soul music.[43][44] The album reflected lineup instability, with drummer Bill Legend departing after an Australian tour and percussionist Mickey Finn soon following, leaving Bolan to rely on session musicians like Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman (formerly of the Turtles) for vocals, alongside core bassist Steve Currie.[31][45] Recorded amid personal and professional pressures, it peaked at No. 12 on the UK Albums Chart but signaled commercial challenges, as T. Rex's chart dominance waned amid punk's rise.[43] The lead single, "(Whatever Happened to the) Teenage Dream?," credited to Marc Bolan with T. Rex, reached No. 13 on the UK Singles Chart in February 1974, capturing Bolan's introspective shift during a brief creative hiatus following the album's sessions.[42][46] By 1975, Bolan self-produced Bolan's Zip Gun, released on February 15, as T. Rex slimmed to a core trio with Currie and new drummer Davey Lutton, emphasizing raw funk-rock hybrids over polished glam.[31][47] Tracks like "Light of Love" and "Zip Gun Boogie" fused electric boogie with soul-inflected rhythms, though the album failed to chart in the UK, highlighting ongoing commercial struggles.[42][48] Futuristic Dragon, issued on January 30, 1976, continued this blend of funk and rock, with Bolan enlisting guests like keyboardist Dino Dines and aiming for a cosmic, orchestral edge in songs such as "Chrome Sitar" and "All Alone."[49] Singles "New York City" (No. 15 UK, July 1975) and "Dreamy Lady" (No. 30 UK, January 1976) offered modest revival signs, peaking the album at No. 50 on the UK Albums Chart.[42][50] In 1977, Bolan hosted the six-part ITV music series Marc, airing from July to September, which featured live performances by emerging punk and new wave acts alongside T. Rex material, including guests like David Bowie, Generation X, and The Boomtown Rats, revitalizing Bolan's public profile.[2][51] This period culminated in T. Rex's final studio album, Dandy in the Underworld, released on March 11, with a refreshed lineup including Lutton and reed player Miller Anderson, blending glam remnants with soulful rock in tracks like the title song and "Cosmic Dancer."[31][52] The single "I Love to Boogie," recorded in 1976, reached No. 13 on the UK Singles Chart in June, indicating a partial creative resurgence before Bolan's death later that year.[42]Personal life

Relationships and marriages

Bolan's romantic life began in his teenage years during his modeling and early music endeavors, where he had several brief relationships, including his first serious relationship with Theresa (Terry) Whipman from 1965 to 1968.[53] These early partnerships reflected his youthful exploration amid the vibrant London scene of the 1960s. In 1968, Bolan met June Ellen Child, a publicist and model four years his senior, who soon became his manager, driver, and romantic partner.<grok:render type="render_inline_citation">Lifestyle and interests

Marc Bolan was renowned as a glam fashion icon, pioneering an androgynous aesthetic that featured corkscrew curls, glittery makeup, custom velvet suits, and a pixie-like image blending elfin whimsy with rock-star flamboyance.[54] His style, often incorporating satin capes, platform boots, and feather boas, influenced designers from Biba to contemporary figures like Harry Styles, establishing him as a trailblazer in gender-fluid fashion during the early 1970s.[55][6] Beyond music, Bolan pursued literary interests, particularly poetry, culminating in his 1969 publication of The Warlock of Love, a collection of 63 mystical verses inspired by fantasy realms and Tolkien-esque imagery.[56] The book reflected his early fascination with wizards, sorcery, and otherworldly themes, aligning with the ethereal vibe of his Tyrannosaurus Rex era. Bolan maintained a vegetarian lifestyle, adhering to a macrobiotic diet of brown rice, lentils, and unseasoned vegetables, which he shared during social gatherings in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[57] His dietary discipline, described by friends as "kosher macroneurotic," emphasized health and purity, though he occasionally relaxed it later in life. This commitment complemented his broader interests in the occult, where he invoked spells, Egyptian deities, and planetary forces in conversations, viewing himself as a "cosmic dancer" attuned to mystical energies.[3] He also held beliefs in astrology, often referencing zodiac influences and horoscopic alignments in his creative process.[58] In his later years, Bolan struggled with drug use, including heavy cocaine consumption starting around 1973, alongside cannabis, brandy, and pills, which fueled paranoia, weight gain, and erratic behavior such as volatile temper outbursts.[59] These habits contributed to a decline in his health and productivity, with him admitting to daily brandy binges and cocaine snorting by 1974.[60] Bolan's lifestyle evolved from bohemian roots in 1960s London squats and bedsits to opulent homes like his residence at 142 Upper Richmond Road West in East Sheen, near Barnes, by the mid-1970s, reflecting his rising stardom.[59] An avid car enthusiast despite never learning to drive—fearing accidents after idolizing Eddie Cochran—he favored a white Mini Cooper, often chauffeured in it or other luxury vehicles like Rolls-Royces, symbolizing his playful yet extravagant tastes.[61]Death and immediate aftermath

The car crash

On the early morning of 16 September 1977, Marc Bolan, aged 29, was killed in a car crash on Queens Ride near Barnes Common in southwest London. He was a front-seat passenger in a purple Mini 1275 GT driven by his girlfriend, the American singer Gloria Jones, as they returned home from a late-night dinner at Morton's restaurant in Berkeley Square. The vehicle, which had recently been serviced, veered off the road at approximately 4:45 a.m., smashing through a steel-reinforced fence before striking a sycamore tree; possible contributing factors included low tire pressure and loose wheel nuts.[61][62][63] Bolan suffered fatal head injuries when an eye bolt from the fence post penetrated his skull, and his seat swiveled 180 degrees upon impact, throwing him into the rear of the car. The official cause of death was shock and hemorrhage from multiple injuries, and he was pronounced dead at the scene. Jones survived with severe facial injuries, including a broken jaw that was wired shut during her hospitalization, but no other passengers were present. This incident followed Bolan's return to the UK earlier that year from tax exile in the US and Monaco, amid plans for renewed activity including a potential US tour that faced logistical hurdles.[61][62][63] An eyewitness, Vicky Aram, who was driving behind the Mini, stopped immediately after hearing the crash and found Jones groaning but semi-conscious in the wreckage. Aram used a rug from her car to gently lay Bolan on the ground, confirming he showed no signs of life, while another passerby attempted to comfort him. Emergency services arrived shortly thereafter, but Bolan could not be revived, marking the end of his life just two weeks before his 30th birthday.[62][59]Funeral and public response

Bolan's funeral was held privately on 20 September 1977 at Golders Green Crematorium in North London, four days after the car crash that claimed his life.[64] The service was attended by close family, T. Rex bandmates including drummer Davey Lutton and bassist Herbie Flowers, and a host of music industry figures such as David Bowie, Rod Stewart, Elton John, Eric Clapton, Tony Visconti, and Les Paul.[64][65] Floral tributes included a large white swan, referencing T. Rex's 1970 hit "Ride a White Swan."[64] Following the cremation, Bolan's ashes were buried under a rose bush in the crematorium's West Statue Bed #5, near a memorial bench dedicated to him that was later installed by fans.[66][67] Contemporary media coverage in outlets like the New Musical Express (NME) and Melody Maker portrayed Bolan's death as a poignant close to the glam rock era he had helped define, with tributes emphasizing his influence on 1970s pop culture amid the rise of punk.[68] Gloria Jones, who survived the crash with a broken jaw and other injuries, recovered in hospital before assuming custody of their two-year-old son, Rolan, and relocating to Los Angeles to live with her family.[69][70] In the immediate aftermath, fans held informal vigils at the crash site on Barnes Common, leaving flowers and messages that evolved into the ongoing Marc Bolan's Rock Shrine.[71] Additionally, plans for a second series of Bolan's Granada Television show Marc, which had aired six episodes earlier that year featuring guests like Bowie and Generation X, were abruptly cancelled following his death.[72][73]Legacy

Musical and cultural influence

Marc Bolan played a pivotal role in pioneering glam rock, transforming the genre through his electrified sound and flamboyant persona during the early 1970s. His March 1971 performance of "Hot Love" on BBC's Top of the Pops, adorned in a silver satin sailor suit with glittery gold teardrops under his eyes, is often cited as the moment glam rock burst into mainstream consciousness, blending pop accessibility with theatrical excess.[54] This shift inspired contemporaries like David Bowie, who drew from Bolan's androgynous style for his Ziggy Stardust persona, acknowledging Bolan's lead by opening for T. Rex in 1969 and later referencing him in songs such as "All the Young Dudes."[74][75] Bolan's influence extended to Slade and Gary Glitter, who adopted similar elements of glitter, platform footwear, and gender-blurring aesthetics to fuel their own chart-topping successes in the glam wave.[75] Bolan's raw, energetic song structures and unpretentious attitude also resonated in the emerging punk and post-punk scenes, bridging glam's spectacle with punk's DIY ethos. Bands like The Damned, Britain's first punk act, cited Bolan's simple, garage-like riffs as a foundational influence, with him personally supporting them by taking them on a 1977 UK tour and collaborating on a version of "Get It On" during a Portsmouth gig.[76] Similarly, Generation X benefited from Bolan's endorsement, appearing on his Granada TV show Marc alongside other punk-new wave outfits, where his endorsement helped legitimize the genre amid establishment backlash.[76][74] This cross-pollination highlighted Bolan's versatility, as his music's primal drive provided a template for punk's rejection of progressive excess. Bolan's fashion innovations left an indelible mark on 1970s youth culture, popularizing glitter, platform boots, and voluminous curls as symbols of rebellion and self-expression. His signature looks—feather boas, sequined Biba blazers, and satin suits paired with mary-jane shoes—challenged traditional masculinity, encouraging men to embrace cosmetics and flamboyance without effeminacy, as he himself stated: “Guys could go out on stage … being not effeminate, but not necessarily having to have Brut aftershave on.”[54] These elements permeated street style and high fashion, shaping a generation's visual identity and influencing designers from Anna Sui to contemporary lines at Gucci and Saint Laurent.[54][74] Through his lyrics, Bolan infused rock with fantasy and mythological themes, drawing from sources like J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings and C.S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia to create vivid worlds of dragons, unicorns, and cosmic dancers.[77] Albums such as Unicorn (1969) and Futuristic Dragon (1976) exemplified this approach, with tracks evoking speculative lore that contrasted punk's grit and echoed in progressive rock's narrative ambitions, encouraging bands to weave mythology into their soundscapes.[77] His poetic surrealism, blending hippie mysticism with pop hooks, helped normalize such imagery in mainstream rock. Bolan's evolution from acoustic folk roots with Tyrannosaurus Rex to electric pop stardom with T. Rex bridged the hippie counterculture and broader mainstream appeal, revitalizing British music post-Beatles.[76] This metamorphosis, marked by hits like "Ride a White Swan" in 1970, fused folk's introspective whimsy with accessible pop energy, drawing hippie audiences into chart dominance and paving the way for glam's commercial explosion.[75][76]Posthumous recognition and revivals

Following Bolan's death, various efforts sought to revive interest in T. Rex through reunions involving surviving band members. In the 1980s and beyond, percussionist Mickey Finn participated in several T. Rex-inspired projects and tours with fan-formed groups, helping sustain the band's live legacy despite the absence of Bolan.[78] Later formations, such as Mickey Finn's T. Rex established in the late 1990s with Finn, guitarist Jack Green, and drummer Paul Fenton, continued touring internationally into the 2000s, even after Finn's death in 2003.[79] In the 1990s, reissues of Bolan's work were released via the Marc On Wax label, operated by former fan club members, which released compilations like the "Rarities" series (1990–1992) and remastered editions of albums such as Electric Warrior.[80] These efforts introduced Bolan's catalog to new audiences through archival material and restored recordings. Bolan's enduring impact was acknowledged in major honors, including T. Rex's induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2020, where Rolan Bolan accepted on behalf of the band.[81] In UK public opinion polls, Bolan ranks as the 86th most popular classic rock artist and 398th overall music artist, reflecting sustained admiration.[82] Numerous artists have paid tribute to Bolan, drawing direct inspiration from his glam rock style. Billy Idol's 1982 debut album was described by reviewers as evoking what Bolan might have produced in the era, capturing a similar blend of punk energy and glittery aesthetics.[83] Oasis, in particular, echoed Bolan's riff-driven sound on tracks like "Cigarettes & Alcohol" from their 1994 album Definitely Maybe, which mirrors the groove of T. Rex's "Get It On (Bang a Gong)."[84] The 2000s and 2010s saw increased media focus on Bolan's life and music, highlighted by the 2007 BBC documentary Marc Bolan: The Final Word, narrated by Suzi Quatro and featuring rare interviews and performances that explored his rise from childhood ambitions to glam icon status.[85] Memorials also proliferated, including a life-size bronze bust unveiled in 2002 at the site of Bolan's fatal crash on Barnes Common, organized by the T. Rex Action Group to commemorate the 25th anniversary of his death. In September 2025, English Heritage unveiled a blue plaque at Bolan's former home in Maida Vale, London, at 31 Clarendon Gardens, where he created hits like "Get It On," further cementing his cultural footprint.[86] Ongoing fan engagement includes annual tributes at Glastonbury Festival, where Bolan headlined the inaugural 1970 event as Tyrannosaurus Rex, inspiring modern celebrations of his pioneering role in British rock.[87] Vinyl revivals have surged in the 2020s, with Demon Records issuing the eight-album box set T. Rex: The Studio Albums 1970–1977 in December 2025, alongside limited-edition reissues like the 50th-anniversary zoetrope picture disc of Zinc Alloy and the Hidden Riders of Tomorrow (2024) and Bolan's Zip Gun (2025), driving renewed collector interest.[88][89]Discography

Studio albums

Marc Bolan's studio albums span his evolution from acoustic folk-psych with Tyrannosaurus Rex to the electric glam rock of T. Rex, reflecting his shift toward pop accessibility and commercial success in the early 1970s. His early solo work under the Tyrannosaurus Rex moniker emphasized poetic, mystical lyrics and sparse instrumentation, while the T. Rex period introduced boogie-infused riffs, string arrangements, and hits that dominated the UK charts. These releases, produced primarily by Tony Visconti, captured Bolan's creative peaks and experiments until his death in 1977.[90][42] The following table lists Bolan's studio albums in chronological order, including release years, UK peak chart positions, certifications where applicable, and unique production notes.| Album Title | Release Year | UK Peak Position | Certification | Production Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Beginning (as Marc Bolan, archival release of demos) | 1974 | Did not chart | None | Recorded as early demos before his duo formation; later compiled and released posthumously, showcasing nascent songwriting with acoustic guitar and poetic themes.[90] |

| My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair... But Now They're Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows (as Tyrannosaurus Rex) | 1968 | #15 (reissue combined with Prophets, Seers & Sages reached #1) | None | Debut album produced by Tony Visconti at Trident Studios; features Bolan and Steve Peregrin Took's acoustic duo sound with bongos and warbling vocals on 13 short tracks exploring mythology.[90][42] |

| Prophets, Seers & Sages: The Angels of the Ages (as Tyrannosaurus Rex) | 1968 | Did not chart (reissue combined with My People Were Fair... reached #1) | None | Quick follow-up recorded in one day; 10 brief, whimsical tracks with fairy-tale lyrics, maintaining the duo's intimate, folk-psych aesthetic under Visconti's production.[90][42] |

| Unicorn (as Tyrannosaurus Rex) | 1969 | #12 | None | Third album with new percussionist Mickey Finn replacing Took; includes electric elements on tracks like "Romany Soup," produced by Visconti with a slightly expanded lineup for more dynamic arrangements.[90][42] |

| T. Rex (as T. Rex) | 1970 | #7 | None | Rebranding debut with electric guitar prominence; half acoustic, half electric tracks recorded at Advision Studios, signaling Bolan's pop shift with hits like "Ride a White Swan" influencing its success.[90][42] |

| Electric Warrior | 1971 | #1 (8 weeks) | Gold (BPI) | Landmark glam rock album produced by Visconti at Trident; features Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman on backing vocals, boogie rhythms, and string sections, with sales exceeding 1.2 million in the UK alone.[90][42][91] |

| The Slider | 1972 | #4 | None | Follow-up recorded in France and the US with Visconti; emphasizes funky grooves and Bolan's lisp-heavy delivery, including "Telegram Sam," amid his "T. Rexit" mania.[90][42] |

| Tanx | 1973 | #4 | None | Produced by Visconti with soul and gospel influences; features brass and female backing singers, marking a transitional phase with tracks like "20th Century Boy."[90][42] |

| Zinc Alloy and the Hidden Riders of Tomorrow | 1974 | #12 | None | Experimental soul-funk album produced by Bolan himself; introduces cosmic themes and R&B elements with new band members, reflecting personal turmoil.[90][42] |

| Bolan's Zip Gun | 1975 | #18 | None | Self-produced with Motown-inspired tracks; recorded quickly at MRI Studios, featuring heavy guitar and falsetto vocals amid declining commercial fortunes.[90][42] |

| Futuristic Dragon | 1976 | #50 | None | Return to production helm by Visconti; blends rock, funk, and psychedelia with sci-fi lyrics, including "Futuristic Dragon (Introduction)," showing renewed energy.[90][42] |

| Dandy in the Underworld | 1977 | #26 | None | Final studio album, co-produced by Bolan and Visconti; upbeat glam revival with tracks like the title song, recorded as Bolan reclaimed his creative spark.[90][42] |

Singles and EPs