Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Heliocentric orbit

View on Wikipedia

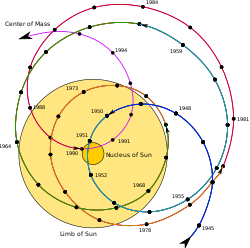

A heliocentric orbit (also called circumsolar orbit) is an orbit around the barycenter of the Solar System, which is usually located within or very near the surface of the Sun. All planets, comets, and asteroids in the Solar System, and the Sun itself are in such orbits, as are many artificial probes and pieces of debris. The moons of planets in the Solar System, by contrast, are not in heliocentric orbits, as they orbit their respective planet (although the Moon has a convex orbit around the Sun).

The barycenter of the Solar System, while always very near the Sun, moves through space as time passes, depending on where other large bodies in the Solar System, such as Jupiter and other large gas giants, are located at that time. A similar phenomenon allows the detection of exoplanets by way of the radial-velocity method.

The helio- prefix is derived from the Greek word "ἥλιος", meaning "Sun", and also Helios, the personification of the Sun in Greek mythology.[1]

The first spacecraft to be put in a heliocentric orbit was Luna 1 in 1959. An incorrectly timed upper-stage burn caused it to miss its planned impact on the Moon.[2]

Trans-Mars injection

[edit]

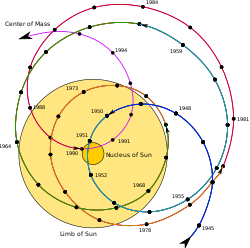

A = Hohmann transfer orbit. B = Conjunction mission. C = Opposition mission

A trans-Mars injection (TMI) is a heliocentric orbit in which a propulsive maneuver is used to set a spacecraft on a trajectory, also known as Mars transfer orbit, which will place it as far as Mars orbit.

Every two years, low-energy transfer windows open up, which allow movement between the two planets with the lowest possible energy requirements. Transfer injections can place spacecraft into either a Hohmann transfer orbit or bi-elliptic transfer orbit. Trans-Mars injections can be either a single maneuver burn, such as that used by the NASA MAVEN orbiter in 2013, or a series of perigee kicks, such as that used by the ISRO Mars Orbiter Mission in 2013.[3][4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "helio-". Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House. 2006. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- ^ "NASA – NSSDCA – Spacecraft – Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-06-02. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ ISRO successfully sends Mars orbiter into sun-centric orbit.

- ^ Orbiter successfully placed in Mars Transfer Trajectory.