Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Heliosphere

View on Wikipedia

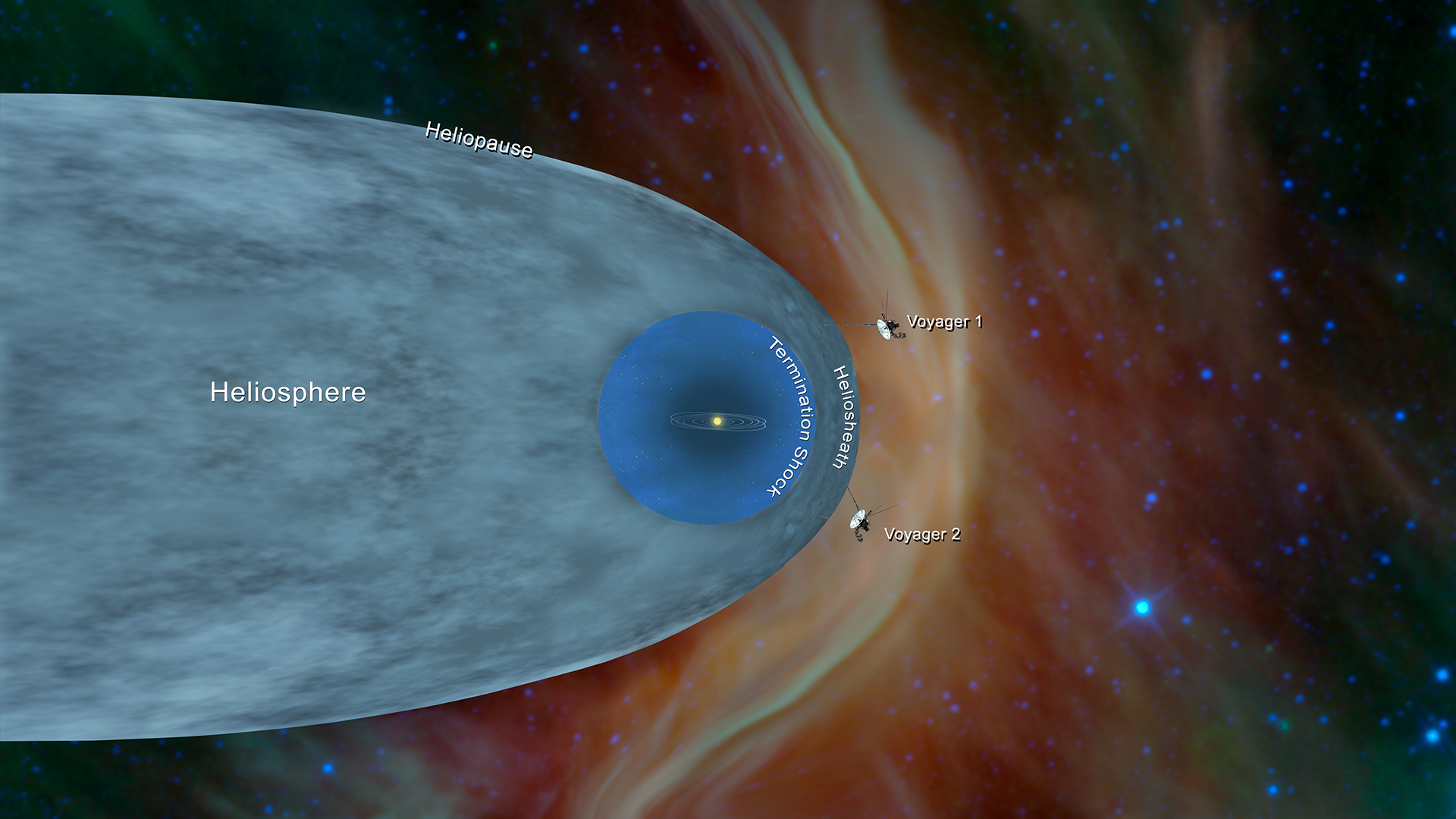

- Top: Diagram of the heliosphere as it travels through the interstellar medium:

- Heliosheath: the outer region of the heliosphere; the solar wind is compressed and turbulent

- Heliopause: the boundary between the solar wind and interstellar wind where they are in equilibrium.

- Middle: water running into a sink as an analogy for the heliosphere and its different zones (left) and Voyager spacecraft measuring a drop of the solar wind's high-energy particles at the termination shock (right)

- Bottom: Logarithmic scale of the Solar System and Voyager 1's position.

The heliosphere is the magnetosphere, astrosphere, and outermost atmospheric layer of the Sun. It takes the shape of a vast, tailed bubble-like region of space. In plasma physics terms, it is the cavity formed by the Sun in the surrounding interstellar medium. The "bubble" of the heliosphere is continuously "inflated" by plasma originating from the Sun, known as the solar wind. Outside the heliosphere, this solar plasma gives way to the interstellar plasma permeating the Milky Way. As part of the interplanetary magnetic field, the heliosphere shields the Solar System from significant amounts of cosmic ionizing radiation; uncharged gamma rays are, however, not affected.[1] Its name was likely coined by Alexander J. Dessler, who is credited with the first use of the word in the scientific literature in 1967.[2] The scientific study of the heliosphere is heliophysics, which includes space weather and space climate.

Flowing unimpeded through the Solar System for billions of kilometers, the solar wind extends far beyond even the region of Pluto until it encounters the "termination shock", where its motion slows abruptly due to the outside pressure of the interstellar medium. The "heliosheath" is a broad transitional region between the termination shock and the heliosphere's outmost edge, the "heliopause". The overall shape of the heliosphere resembles that of a comet, being roughly spherical on one side to around 100 astronomical units (AU), and on the other side being tail shaped, known as the "heliotail", trailing for several thousands of AUs.

Two Voyager program spacecraft explored the outer reaches of the heliosphere, passing through the termination shock and the heliosheath. Voyager 1 encountered the heliopause on 25 August 2012, when the spacecraft measured a sudden forty-fold increase in plasma density.[3] Voyager 2 traversed the heliopause on 5 November 2018.[4] Because the heliopause marks the boundary between matter originating from the Sun and matter originating from the rest of the galaxy, spacecraft that depart the heliosphere (such as the two Voyagers) are in interstellar space.

History

[edit]The heliosphere is thought to change significantly over the course of millions of years due to extrasolar effects such as closer supernovas or the traversing interstellar medium of different densities. Evidence suggests that up to three million years ago Earth was exposed to the interstellar medium due to it shrinking the heliosphere to the Inner Solar System, which possibly had impacted Earth's past climate and human evolution.[5]

Structure

[edit]

Despite its name, the heliosphere's shape is not a perfect sphere.[6] Its shape is determined by three factors: the interstellar medium (ISM), the solar wind, and the overall motion of the Sun and heliosphere as it passes through the ISM. Because the solar wind and the ISM are both fluid, the heliosphere's shape and size are also fluid. Changes in the solar wind, however, more strongly alter the fluctuating position of the boundaries on short timescales (hours to a few years). The solar wind's pressure varies far more rapidly than the outside pressure of the ISM at any given location. In particular, the effect of the 11-year solar cycle, which sees a distinct maximum and minimum of solar wind activity, is thought to be significant.

On a broader scale, the motion of the heliosphere through the fluid medium of the ISM results in an overall comet-like shape. The solar wind plasma which is moving roughly "upstream" (in the same direction as the Sun's motion through the galaxy) is compressed into a nearly-spherical form, whereas the plasma moving "downstream" (opposite the Sun's motion) flows out for a much greater distance before giving way to the ISM, defining the long, trailing shape of the heliotail.

The limited data available and the unexplored nature of these structures have resulted in many theories as to their form.[7] In 2020, Merav Opher led the team of researchers who determined that the shape of the heliosphere is a crescent[8] that can be described as a deflated croissant.[9][10]

Solar wind

[edit]The solar wind consists of particles (ionized atoms from the solar corona) and fields like the magnetic field that are produced from the Sun and stream out into space. Because the Sun rotates once approximately every 25 days, the heliospheric magnetic field[11] transported by the solar wind gets wrapped into a spiral. The solar wind affects many other systems in the Solar System; for example, variations in the Sun's own magnetic field are carried outward by the solar wind, producing geomagnetic storms in the Earth's magnetosphere.

Heliospheric current sheet

[edit]The heliospheric current sheet is a ripple in the heliosphere created by the rotating magnetic field of the Sun. It marks the boundary between heliospheric magnetic field regions of opposite polarity. Extending throughout the heliosphere, the heliospheric current sheet could be considered the largest structure in the Solar System and is said to resemble a "ballerina's skirt".[12]

Edge structure

[edit]The outer structure of the heliosphere is determined by the interactions between the solar wind and the winds of interstellar space. The solar wind streams away from the Sun in all directions at speeds of several hundred km/s in the Earth's vicinity. At some distance from the Sun, well beyond the orbit of Neptune, this supersonic wind slows down as it encounters the gases in the interstellar medium. This takes place in several stages:

- The solar wind is traveling at supersonic speeds within the Solar System. At the termination shock, a standing shock wave, the solar wind falls below the speed of sound and becomes subsonic.

- It was previously thought that once subsonic, the solar wind would be shaped by the ambient flow of the interstellar medium, forming a blunt nose on one side and comet-like heliotail behind, a region called the heliosheath. However, observations in 2009 showed that this model is incorrect.[13][14] As of 2011, it is thought to be filled with a magnetic bubble "foam".[15]

- The outer surface of the heliosheath, where the heliosphere meets the interstellar medium, is called heliopause. This is the edge of the entire heliosphere. Observations in 2009 led to changes to this model.[13][14]

- In theory, heliopause causes turbulence in the interstellar medium as the Sun orbits the Galactic Center. This turbulence results from the pressure of the advancing heliopause against the interstellar medium. However, the velocity of the solar wind relative to the interstellar medium may be too low for a bow shock.[16]

Termination shock

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (January 2019) |

The termination shock is the point in the heliosphere where the solar wind slows down to subsonic speed (relative to the Sun) because of interactions with the local interstellar medium. This causes compression, heating, and a change in the magnetic field. In the Solar System, the termination shock is believed to be 75 to 90 astronomical units[17] from the Sun. In 2004, Voyager 1 crossed the Sun's termination shock, followed by Voyager 2 in 2007.[3][6][18][19][20][21][22][23][excessive citations]

The shock arises because solar wind particles are emitted from the Sun at about 400 km/s, while the speed of sound (in the interstellar medium) is about 100 km/s. The exact speed depends on the density, which fluctuates considerably. The interstellar medium, although very low in density, nonetheless has a relatively constant pressure associated with it; the pressure from the solar wind decreases with the square of the distance from the Sun. As one moves far enough away from the Sun, the pressure of the solar wind drops to where it can no longer maintain supersonic flow against the pressure of the interstellar medium, at which point the solar wind slows to below its speed of sound, causing a shock wave. Further from the Sun, the termination shock is followed by heliopause, where the two pressures become equal and solar wind particles are stopped by the interstellar medium.

Other termination shocks can be seen in terrestrial systems; perhaps the easiest may be seen by simply running a water tap into a sink creating a hydraulic jump. Upon hitting the floor of the sink, the flowing water spreads out at a speed that is higher than the local wave speed, forming a disk of shallow, rapidly diverging flow (analogous to the tenuous, supersonic solar wind). Around the periphery of the disk, a shock front or wall of water forms; outside the shock front, the water moves slower than the local wave speed (analogous to the subsonic interstellar medium).

Evidence presented at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in May 2005 by Ed Stone suggests that the Voyager 1 spacecraft passed the termination shock in December 2004, when it was about 94 AU from the Sun, by virtue of the change in magnetic readings taken from the craft. In contrast, Voyager 2 began detecting returning particles when it was only 76 AU from the Sun, in May 2006. This implies that the heliosphere may be irregularly shaped, bulging outwards in the Sun's northern hemisphere and pushed inward in the south.[24]

Heliosheath

[edit]The heliosheath is the region of the heliosphere beyond the termination shock. Here the wind is slowed, compressed, and made turbulent by its interaction with the interstellar medium. At its closest point, the inner edge of the heliosheath lies approximately 80 to 100 AU from the Sun. A proposed model hypothesizes that the heliosheath is shaped like the coma of a comet, and trails several times that distance in the direction opposite to the Sun's path through space. At its windward side, its thickness is estimated to be between 10 and 100 AU.[26] Voyager project scientists have determined that the heliosheath is not "smooth" – it is rather a "foamy zone" filled with magnetic bubbles, each about 1 AU wide.[15] These magnetic bubbles are created by the impact of the solar wind and the interstellar medium.[27][28] Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 began detecting evidence of the bubbles in 2007 and 2008, respectively. The probably sausage-shaped bubbles are formed by magnetic reconnection between oppositely oriented sectors of the solar magnetic field as the solar wind slows down. They probably represent self-contained structures that have detached from the interplanetary magnetic field.

At a distance of about 113 AU, Voyager 1 detected a 'stagnation region' within the heliosheath.[29] In this region, the solar wind slowed to zero,[30][31][32][33] the magnetic field intensity doubled and high-energy electrons from the galaxy increased 100-fold. At about 122 AU, the spacecraft entered a new region that Voyager project scientists called the "magnetic highway", an area still under the influence of the Sun but with some dramatic differences.[34]

Heliopause

[edit]The heliopause is the theoretical boundary where the Sun's solar wind is stopped by the interstellar medium; where the solar wind's strength is no longer great enough to push back the stellar winds of the surrounding stars. This is the boundary where the interstellar medium and solar wind pressures balance. The crossing of the heliopause should be signaled by a sharp drop in the temperature of solar wind-charged particles,[31] a change in the direction of the magnetic field, and an increase in the number of galactic cosmic rays.[35]

In May 2012, Voyager 1 detected a rapid increase in such cosmic rays (a 9% increase in a month, following a more gradual increase of 25% from January 2009 to January 2012), suggesting it was approaching the heliopause.[35] Between late August and early September 2012, Voyager 1 witnessed a sharp drop in protons from the Sun, from 25 particles per second in late August, to about 2 particles per second by early October.[36] In September 2013, NASA announced that Voyager 1 had crossed the heliopause as of 25 August 2012.[37] This was at a distance of 121 AU (1.81×1010 km) from the Sun.[38] Contrary to predictions, data from Voyager 1 indicates the magnetic field of the galaxy is aligned with the solar magnetic field.[39]

On November 5, 2018, the Voyager 2 mission detected a sudden decrease in the flux of low-energy ions. At the same time, the level of cosmic rays increased. This demonstrated that the spacecraft crossed the heliopause at a distance of 119 AU (1.78×1010 km) from the Sun. Unlike Voyager 1, the Voyager 2 spacecraft did not detect interstellar flux tubes while crossing the heliosheath.[40]

NASA also collected data from the heliopause remotely during the suborbital SHIELDS mission in 2021.[41]

Heliotail

[edit]The heliotail is the several thousand astronomical units long tail of the heliosphere,[5] and thus the Solar System's tail. It can be compared to the tail of a comet (however, a comet's tail does not stretch behind it as it moves; it is always pointing away from the Sun). The tail is a region where the Sun's solar wind slows down and ultimately escapes the heliosphere, slowly evaporating because of charge exchange.[42] The shape of the heliotail (as found by NASA's Interstellar Boundary Explorer – IBEX) is that of a four-leaf clover.[43] The particles in the tail do not shine, therefore it cannot be seen with conventional optical instruments. IBEX made the first observations of the heliotail by measuring the energy of "energetic neutral atoms", neutral particles created by collisions in the Solar System's boundary zone.[43]

The tail has been shown to contain fast and slow particles; the slow particles are on the side and the fast particles are encompassed in the center. The shape of the tail can be linked to the Sun sending out fast solar winds near its poles and slow solar winds near its equator more recently. The clover-shaped tail moves further away from the Sun, which makes the charged particles begin to morph into a new orientation.

Cassini and IBEX data challenged the "heliotail" theory in 2009.[13][14] In July 2013, IBEX results revealed a 4-lobed tail on the Solar System's heliosphere.[44]

Outside structures

[edit]The heliopause is the final known boundary between the heliosphere and the interstellar space that is filled with material, especially plasma, not from the Earth's own star, the Sun, but from other stars.[46] Even so, just outside the heliosphere (i.e. the "solar bubble") there is a transitional region, as detected by Voyager 1.[47] Just as some interstellar pressure was detected as early as 2004, some of the Sun's material seeps into the interstellar medium.[47] The heliosphere is thought to reside in the Local Interstellar Cloud inside the Local Bubble, which is a region in the Orion Arm of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Outside the heliosphere, there is a forty-fold increase in plasma density.[47] There is also a radical reduction in the detection of certain types of particles from the Sun, and a large increase in galactic cosmic rays.[48]

The flow of the interstellar medium (ISM) into the heliosphere has been measured by at least 11 different spacecraft as of 2013.[49] By 2013, it was suspected that the direction of the flow had changed over time.[49] The flow, coming from Earth's perspective from the constellation Scorpius, has probably changed direction by several degrees since the 1970s.[49]

Hydrogen wall

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (January 2019) |

Predicted to be a region of hot hydrogen, a structure called the "hydrogen wall" may be between the bow shock and the heliopause.[50] The wall is composed of interstellar material interacting with the edge of the heliosphere. One paper released in 2013 studied the concept of a bow wave and hydrogen wall.[51]

Another hypothesis suggests that the heliopause could be smaller on the side of the Solar System facing the Sun's orbital motion through the galaxy. It may also vary depending on the current velocity of the solar wind and the local density of the interstellar medium. It is known to lie far outside the orbit of Neptune. The mission of the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft is to find and study the termination shock, heliosheath, and heliopause. Meanwhile, the IBEX mission is attempting to image the heliopause from Earth orbit within two years of its 2008 launch. Initial results (October 2009) from IBEX suggest that previous assumptions are insufficiently cognizant of the true complexities of the heliopause.[52]

In August 2018, long-term studies about the hydrogen wall by the New Horizons spacecraft confirmed results first detected in 1992 by the two Voyager spacecraft.[53][54] Although the hydrogen is detected by extra ultraviolet light (which may come from another source), the detection by New Horizons corroborates the earlier detections by Voyager at a much higher level of sensitivity.[55]

Bow shock

[edit]It was long hypothesized that the Sun produces a "shock wave" in its travels within the interstellar medium. It would occur if the interstellar medium is moving supersonically "toward" the Sun, since its solar wind moves "away" from the Sun supersonically. When the interstellar wind hits the heliosphere it slows and creates a region of turbulence. A bow shock was thought to possibly occur at about 230 AU,[17] but in 2012 it was determined it probably does not exist.[16] This conclusion resulted from new measurements: The velocity of the LISM (local interstellar medium) relative to the Sun's was previously measured to be 26.3 km/s by Ulysses, whereas IBEX measured it at 23.2 km/s.[56]

This phenomenon has been observed outside the Solar System, around stars other than the Sun, by NASA's now retired orbital GALEX telescope. The red giant star Mira in the constellation Cetus has been shown to have both a debris tail of ejecta from the star and a distinct shock in the direction of its movement through space (at over 130 kilometers per second).

Observational methods

[edit]

Detection by spacecraft

[edit]The precise distance to and shape of the heliopause are still uncertain. Interplanetary/interstellar spacecraft such as Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11 and New Horizons are traveling outward through the Solar System and will eventually pass through the heliopause. Contact to Pioneer 10 and 11 has been lost.

Cassini results

[edit]Rather than a comet-like shape, the heliosphere appears to be bubble-shaped according to data from Cassini's Ion and Neutral Camera (MIMI / INCA). Rather than being dominated by the collisions between the solar wind and the interstellar medium, the INCA (ENA) maps suggest that the interaction is controlled more by particle pressure and magnetic field energy density.[13][58]

IBEX results

[edit]

Initial data from Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX), launched in October 2008,[59] revealed a previously unpredicted "very narrow ribbon that is two to three times brighter than anything else in the sky", now known as the IBEX ribbon.[14] Initial interpretations suggest that "the interstellar environment has far more influence on structuring the heliosphere than anyone previously believed"[60] "No one knows what is creating the ENA (energetic neutral atoms) ribbon, ..."[61]

"The IBEX results are truly remarkable! What we are seeing in these maps does not match with any of the previous theoretical models of this region. It will be exciting for scientists to review these (ENA) maps and revise the way we understand our heliosphere and how it interacts with the galaxy."[62] In October 2010, significant changes were detected in the ribbon after 6 months, based on the second set of IBEX observations.[63] IBEX data did not support the existence of a bow shock,[16] but there might be a 'bow wave' according to one study.[51]

Locally

[edit]

Examples of missions that have or continue to collect data related to the heliosphere include:

- Solar Anomalous and Magnetospheric Particle Explorer

- Solar and Heliospheric Observatory

- Solar Dynamics Observatory

- STEREO

- Ulysses spacecraft

- Parker Solar Probe

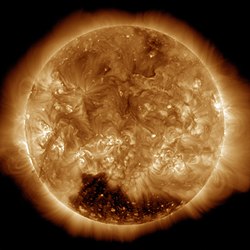

During a total eclipse the high-temperature corona can be more readily observed from Earth solar observatories. During the Apollo program the Solar wind was measured on the Moon via the Solar Wind Composition Experiment. Some examples of Earth surface based Solar observatories include the McMath–Pierce solar telescope or the newer GREGOR Solar Telescope, and the refurbished Big Bear Solar Observatory.

Exploration history

[edit]

The heliosphere is the area under the influence of the Sun; the two major components to determining its edge are the heliospheric magnetic field and the solar wind from the Sun. Three major sections from the beginning of the heliosphere to its edge are the termination shock, the heliosheath, and the heliopause. Five spacecraft have returned much of the data about its furthest reaches, including Pioneer 10 (1972–1997; data to 67 AU), Pioneer 11 (1973–1995; 44 AU), Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 (launched 1977, ongoing), and New Horizons (launched 2006). A type of particle called an energetic neutral atom (ENA) has also been observed to have been produced from its edges.

Except for regions near obstacles such as planets or comets, the heliosphere is dominated by material emanating from the Sun, although cosmic rays, fast-moving neutral atoms, and cosmic dust can penetrate the heliosphere from the outside. Originating at the extremely hot surface of the corona, solar wind particles reach escape velocity, streaming outwards at 300 to 800 km/s (671 thousand to 1.79 million mph or 1 to 2.9 million km/h).[64] As it begins to interact with the interstellar medium, its velocity slows to a stop. The point where the solar wind becomes slower than the speed of sound is called the termination shock; the solar wind continues to slow as it passes through the heliosheath leading to a boundary called the heliopause, where the interstellar medium and solar wind pressures balance. The termination shock was traversed by Voyager 1 in 2004,[34] and Voyager 2 in 2007.[6]

It was thought that beyond the heliopause there was a bow shock, but data from Interstellar Boundary Explorer suggested the velocity of the Sun through the interstellar medium is too low for it to form.[16] It may be a more gentle "bow wave".[51]

Voyager data led to a new theory that the heliosheath has "magnetic bubbles" and a stagnation zone.[29][65] Also, there were reports of a "stagnation region" within the heliosheath, starting around 113 au (1.69×1010 km; 1.05×1010 mi), detected by Voyager 1 in 2010.[29] There, the solar wind velocity drops to zero, the magnetic field intensity doubles, and high-energy electrons from the galaxy increase 100-fold.[29]

Starting in May 2012 at 120 au (1.8×1010 km; 1.1×1010 mi), Voyager 1 detected a sudden increase in cosmic rays, an apparent sign of approach to the heliopause.[35] In the summer of 2013, NASA announced that Voyager 1 had reached interstellar space as of 25 August 2012.[37]

In December 2012, NASA announced that in late August 2012, Voyager 1, at about 122 au (1.83×1010 km; 1.13×1010 mi) from the Sun, entered a new region they called the "magnetic highway", an area still under the influence of the Sun but with some dramatic differences.[34]

Pioneer 10 was launched in March 1972, and within 10 hours passed by the Moon; over the next 35 years or so the mission would be the first out, laying out many firsts of discoveries about the nature of heliosphere as well as Jupiter's impact on it.[66] Pioneer 10 was the first spacecraft to detect sodium and aluminum ions in the solar wind, as well as helium in the inner Solar System.[66] In November 1972, Pioneer 10 encountered Jupiter's enormous (compared to Earth) magnetosphere and would pass in and out of it and its heliosphere 17 times charting its interaction with the solar wind.[66] Pioneer 10 returned scientific data until March 1997, including data on the solar wind out to about 67 AU.[67] It was also contacted in 2003 when it was a distance of 7.6 billion miles from Earth (82 AU), but no instrument data about the solar wind was returned then.[68][69]

Voyager 1 surpassed the radial distance from the Sun of Pioneer 10 at 69.4 AU on 17 February 1998, because it was traveling faster, gaining about 1.02 AU per year.[70] On July 18, 2023, Voyager 2 overtook Pioneer 10 as the second most distant human-made object from the Sun.[71] Pioneer 11, launched a year after Pioneer 10, took similar data as Pioneer out to 44.7 AU in 1995 when that mission was concluded.[69] Pioneer 11 had a similar instrument suite as 10 but also had a flux-gate magnetometer.[70] Pioneer and Voyager spacecraft were on different trajectories and thus recorded data on the heliosphere in different overall directions away from the Sun.[69] Data obtained from Pioneer and Voyager spacecraft helped corroborate the detection of a hydrogen wall.[72]

In 2012 Voyager 1 is thought to have passed through heliopause, and Voyager 2 did the same in 2018.[73][74]

The twin Voyagers are the only man-made objects to have entered interstellar space. However, while they have left the heliosphere, they have not yet left the boundary of the Solar System which is considered to be the outer edge of the Oort Cloud.[74] Upon passing the heliopause, Voyager 2's Plasma Science Experiment (PLS) observed a sharp decline in the speed of solar wind particles on 5 November and there has been no sign of it since. The three other instruments on board measuring cosmic rays, low-energy charged particles, and magnetic fields also recorded the transition.[75] The observations complement data from NASA's IBEX mission. NASA is also preparing an additional mission, Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) which is due to launch in 2025 to capitalize on Voyager's observations.[74]

Timeline of exploration and detection

[edit]- 1904: Astronomers using the Potsdam Great Refractor with a spectrograph find evidence of the interstellar medium while observing the binary star Mintaka in Orion.[76]

- January 1959: Luna 1 becomes the first spacecraft to observe the solar wind.[77]

- 1962: Mariner 2 detects the solar wind.[78]

- 1972–1973: Pioneer 10 becomes the first spacecraft to explore the heliosphere past Mars, flying by Jupiter on 4 December 1973 and continuing to return solar wind data out to a distance of 67 AU.[69]

- February 1992: After flying by Jupiter, the Ulysses spacecraft becomes the first to explore the mid and high latitudes of the heliosphere.[79]

- 1992: Pioneer and Voyager probes detected Ly-α radiation resonantly scattered by heliospheric hydrogen.[72]

- 2004: Voyager 1 becomes the first spacecraft to reach the termination shock.[34]

- 2005: SOHO observations of the solar wind show that the shape of the heliosphere is not axisymmetrical, but distorted, very likely under the effect of the local galactic magnetic field.[80]

- 2009: IBEX project scientists discover and map a ribbon-shaped region of intense energetic neutral atom emission. These neutral atoms are thought to be originating from the heliopause.[14]

- October 2009: the heliosphere may be bubble, not comet shaped.[13]

- October 2010: significant changes were detected in the ribbon after six months, based on the second set of IBEX observations.[63]

- May 2012: IBEX data implies there is probably not a bow "shock".[16]

- June 2012: At 119 AU, Voyager 1 detected an increase in cosmic rays.[35]

- 25 August 2012: Voyager 1 crosses the heliopause, becoming the first human-made object to depart the heliosphere.[3]

- August 2018: long-term studies about the hydrogen wall by the New Horizons spacecraft confirmed results first detected in 1992 by the two Voyager spacecraft.[53][54]

- 5 November 2018: Voyager 2 crosses the heliopause, departing the heliosphere.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Martha, Gale (1 April 2013). "The Sun's Heliosphere". Scientific Explorer.

- ^ J. Dessler, Alexander (February 1967). "Solar wind and interplanetary magnetic field". Reviews of Geophysics and Space Physics. 5 (1): 1–41. Bibcode:1967RvGSP...5....1D. doi:10.1029/RG005i001p00001.

- ^ a b c "NASA Spacecraft Embarks on Historic Journey Into Interstellar Space". NASA. 12 September 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b "NASA's Voyager 2 Probe Enters Interstellar Space". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 10 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ a b Brandt, P. C.; Provornikova, E.; Bale, S. D.; Cocoros, A.; DeMajistre, R.; Dialynas, K.; Elliott, H. A.; Eriksson, S.; Fields, B.; Galli, A.; Hill, M. E.; Horanyi, M.; Horbury, T.; Hunziker, S.; Kollmann, P.; Kinnison, J.; Fountain, G.; Krimigis, S. M.; Kurth, W. S.; Linsky, J.; Lisse, C. M.; Mandt, K. E.; Magnes, W.; McNutt, R. L.; Miller, J.; Moebius, E.; Mostafavi, P.; Opher, M.; Paxton, L.; Plaschke, F.; Poppe, A. R.; Roelof, E. C.; Runyon, K.; Redfield, S.; Schwadron, N.; Sterken, V.; Swaczyna, P.; Szalay, J.; Turner, D.; Vannier, H.; Wimmer-Schweingruber, R.; Wurz, P.; Zirnstein, E. J. (2023). "Future Exploration of the Outer Heliosphere and Very Local Interstellar Medium by Interstellar Probe". Space Science Reviews. 219 (2): 18. Bibcode:2023SSRv..219...18B. doi:10.1007/s11214-022-00943-x. ISSN 0038-6308. PMC 9974711. PMID 36874191.

- ^ a b c "Voyager 2 Proves Solar System Is Squashed". NASA. 10 December 2007. Archived from the original on 25 November 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Matson, J. (27 June 2013). "Voyager 1 Returns Surprising Data about an Unexplored Region of Deep Space". Scientific American. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Opher, Merav; Loeb, Abraham; Drake, James; Toth, Gabor (1 July 2020). "A small and round heliosphere suggested by magnetohydrodynamic modelling of pick-up ions". Nature Astronomy. 4 (7): 675–683. arXiv:1808.06611. Bibcode:2020NatAs...4..675O. doi:10.1038/s41550-020-1036-0. hdl:2144/40769. ISSN 2397-3366. S2CID 216241125.

- ^ Jean, Celia; Reich, Aaron (9 August 2020). "Solar system's heliosphere may be croissant-shaped – study". The Jerusalem Post. ISSN 0792-822X. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Crowley, James (11 August 2020). "NASA says we all live inside a giant "deflated croissant", yes really". Newsweek. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Owens, Mathew J.; Forsyth, Robert J. (28 November 2013). "The Heliospheric Magnetic Field". Living Reviews in Solar Physics. 10 (1): 5. Bibcode:2013LRSP...10....5O. doi:10.12942/lrsp-2013-5. ISSN 1614-4961.

- ^ Mursula, K.; Hiltula, T. (2003). "Bashful ballerina: Southward shifted heliospheric current sheet". Geophysical Research Letters. 30 (22): 2135. Bibcode:2003GeoRL..30.2135M. doi:10.1029/2003GL018201. ISSN 0094-8276.

- ^ a b c d e Johns Hopkins University (18 October 2009). "New View Of The Heliosphere: Cassini Helps Redraw Shape Of Solar System". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "First IBEX Maps Reveal Fascinating Interactions Occurring At The Edge Of The Solar System". 16 October 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b Zell, Holly (7 June 2013). "A Big Surprise from the Edge of the Solar System". Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "New Interstellar Boundary Explorer data show heliosphere's long-theorized bow shock does not exist". Phys.org. 10 May 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (24 June 2002). "The Sun's Heliosphere & Heliopause". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "MIT instrument finds surprises at solar system's edge". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 10 December 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ Steigerwald, Bill (24 May 2005). "Voyager Enters Solar System's Final Frontier". American Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ^ "Voyager 2 Proves Solar System Is Squashed". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 10 December 2007. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ^ A. Gurnett, Donald (1 June 2005). "Voyager Termination Shock". Department of Physics and Astronomy (University of Iowa). Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ Biever, Celeste (25 May 2005). "Voyager 1 reaches the edge of the solar system". New Scientist. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ Shiga, David (10 December 2007). "Voyager 2 probe reaches solar system boundary". New Scientist. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ Than, Ker (24 May 2006). "Voyager II detects solar system's edge". CNN. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ^ JPL.NASA.GOV. "Voyager – The Interstellar Mission". Archived from the original on 8 July 2013.

- ^ Brandt, Pontus (27 February – 2 March 2007). "Imaging of the Heliospheric Boundary" (PDF). NASA Advisory Council Workshop on Science Associated with the Lunar Exploration Architecture: White Papers. Tempe, Arizona: Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ^ Cook, J.-R. (9 June 2011). "NASA Probes Suggest Magnetic Bubbles Reside At Solar System Edge". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ Rayl, A. j. s. (12 June 2011). "Voyager Discovers Possible Sea of Huge, Turbulent, Magnetic Bubbles at Solar System Edge". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d Zell, Holly (5 December 2011). "NASA's Voyager Hits New Region at Solar System Edge". NASA. Archived from the original on 8 March 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (14 December 2010). "Voyager near Solar Systems edge". BBC News. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ a b "NASA's Voyager 1 Spacecraft Nearing Edge of the Solar System". Space.Com. 13 December 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Brumfiel, G. (15 June 2011). "Voyager at the edge: spacecraft finds unexpected calm at the boundary of Sun's bubble". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.370.

- ^ Krimigis, S. M.; Roelof, E. C.; Decker, R. B.; Hill, M. E. (16 June 2011). "Zero outward flow velocity for plasma in a heliosheath transition layer". Nature. 474 (7351): 359–361. Bibcode:2011Natur.474..359K. doi:10.1038/nature10115. PMID 21677754. S2CID 4345662.

- ^ a b c d "NASA Voyager 1 Encounters New Region in Deep Space". Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ^ a b c d "NASA – Data From NASA's Voyager 1 Point to Interstellar Future". NASA. 14 June 2012. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ "Voyager probes to leave solar system by 2016". NBCnews. 30 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b Greicius, Tony (5 May 2015). "NASA Spacecraft Embarks on Historic Journey Into Interstellar Space". Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Cowen, R. (2013). "Voyager 1 has reached interstellar space". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.13735. S2CID 123728719.

- ^ Vergano, Dan (14 September 2013). "Voyager 1 Leaves Solar System, NASA Confirms". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 13 September 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ Stone, E. C.; Cummings, A. C.; Heikkila, B.C.; Lal, Nand (2019). "Cosmic ray measurements from Voyager 2 as it crossed into interstellar space". Nature Astronomy. 3 (11): 1013–1018. Bibcode:2019NatAs...3.1013S. doi:10.1038/s41550-019-0928-3. S2CID 209962964.

- ^ Hatfield, Miles (15 April 2021). "SHIELDS Up! NASA Rocket to Survey Our Solar System's Windshield". NASA. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

The NASA black Brant IX sounding rocket carried the payload to an apogee of 177 miles before descending by parachute and landing at White Sands. Preliminary indications show that vehicle systems performed as planned and data was received.

- ^ "The Unexpected Structure of the Heliotail". Astrobiology Magazine. 12 July 2013.

- ^ a b Cole, Steve (10 July 2013). "NASA Satellite Provides First View of the Solar System's Tail". NASA.gov. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Zell, Holly (6 March 2015). "IBEX Provides First View Of the Solar System's Tail". Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "NASA – STEREO Creates First Images of the Solar System's Invisible Frontier".

- ^ Greicius, Tony (11 September 2013). "Voyager Glossary". Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Greicius, Tony (5 May 2015). "NASA Spacecraft Embarks on Historic Journey Into Interstellar Space". Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "How Do We Know When Voyager Reaches Interstellar Space?". Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ^ a b c Zell, Holly (6 March 2015). "Interstellar Wind Changed Direction Over 40 Years". Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Wood, B. E.; Alexander, W. R.; Linsky, J. L. (13 July 2006). "The Properties of the Local Interstellar Medium and the Interaction of the Stellar Winds of \epsilon Indi and \lambda Andromedae with the Interstellar Environment". American Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on 14 June 2000. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ^ a b c Zank, G. P.; Heerikhuisen, J.; Wood, B. E.; Pogorelov, N. V.; Zirnstein, E.; McComas, D. J. (1 January 2013). "Heliospheric Structure: The Bow Wave and the Hydrogen Wall". Astrophysical Journal. 763 (1): 20. Bibcode:2013ApJ...763...20Z. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/763/1/20.

- ^ Palmer, Jason (15 October 2009). "BBC News article". Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ a b Gladstone, G. Randall; Pryor, W. R.; Stern, S. Alan; Ennico, Kimberly; et al. (7 August 2018). "The Lyman-α Sky Background as Observed by New Horizons". Geophysical Research Letters. 45 (16): 8022–8028. arXiv:1808.00400. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45.8022G. doi:10.1029/2018GL078808. S2CID 119395450.

- ^ a b Letzter, Rafi (9 August 2018). "NASA Spotted a Vast, Glowing 'Hydrogen Wall' at the Edge of Our Solar System". Live Science. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "NASA Spotted a Vast, Glowing 'Hydrogen Wall' at the Edge of Our Solar System". Live Science. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "No Shocks for This Bow: IBEX Says We're Wrong". 14 May 2012. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ "Pioneer H, Jupiter Swingby Out-of-the-Ecliptic Mission Study" (PDF). 20 August 1971. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ NASA – photojournal (15 October 2009). "The Bubble of Our Solar System". Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "IBEX - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. 4 December 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Oct.15/09 IBEX team announcement at http://ibex.swri.edu/

- ^ Kerr, Richard A. (2009). "Tying Up the Solar System With a Ribbon of Charged Particles". Science. 326 (5951): 350–351. doi:10.1126/science.326_350a. PMID 19833930.

- ^ Dave McComas, IBEX Principal Investigator at http://ibex.swri.edu/

- ^ a b "The Ever-Changing Edge of the Solar System". 2 October 2010. Archived from the original on 6 February 2019.

- ^ "NASA/Marshall Solar Physics". solarscience.msfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "NASA – Voyager – Conditions At Edge Of Solar System". NASA. 9 June 2011. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "Pioneer 10: first probe to leave the inner solar system & precursor to Juno". www.NASASpaceFlight.com. 15 July 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "NASA – Pioneer-10 and Pioneer-11". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "NASA – Pioneer 10 Spacecraft Sends Last Signal". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 12 January 2005. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Pioneer 10–11". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b Administrator, NASA Content (3 March 2015). "The Pioneer Missions". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "Voyager 1 has left the Solar System. Will we ever overtake it?". 23 May 2022.

- ^ a b Thomas, Hall, Doyle (1992). "Ultraviolet resonance radiation and the structure of the heliosphere". University of Arizona Repository. Bibcode:1992PhDT........12H.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Voyager 2 Approaches Interstellar Space". Sky & Telescope. 10 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Potter, Sean (9 December 2018). "NASA's Voyager 2 Probe Enters Interstellar Space". NASA. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "Voyager 2 crosses solar boundary, moves into interstellar space". Astronomy Now. 10 December 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Kanipe, Jeff (27 January 2011). The Cosmic Connection: How Astronomical Events Impact Life on Earth. Prometheus Books. pp. 154–155. ISBN 9781591028826.

- ^ "Luna 1". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- ^ "50th Anniversary: Mariner 2, The Venus Mission – NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory". www.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ "Fact Sheet". European Space Agency. 15 March 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- ^ Lallement, R.; Quémerais, E.; Bertaux, J. L.; Ferron, S.; Koutroumpa, D.; Pellinen, R. (March 2005). "Deflection of the Interstellar Neutral Hydrogen Flow Across the Heliospheric Interface". Science. 307 (5714): 1447–1449.(SciHomepage). Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1447L. doi:10.1126/science.1107953. PMID 15746421. S2CID 36260574.

Sources

[edit]- "Heliopause Seems to Be 23 Billion Kilometres". Universe Today. 9 December 2003. Retrieved 8 August 2007.

- "Space probes reveal Solar System's bullet shape". COSMOS magazine. 11 May 2007. Archived from the original on 13 May 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

Further reading

[edit]- Schwadron, Nathan A.; et al. (September 2011). "Does the space environment affect the ecosphere?". Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union. 92 (36): 297–298. Bibcode:2011EOSTr..92..297S. doi:10.1029/2011EO360001. ISSN 0096-3941.

- Gough, Evan (7 August 2020). "This is What the Solar System Really Looks Like". Universe Today. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

External links

[edit]Heliosphere

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Characteristics

The heliosphere is a vast, bubble-like region of space dominated by the outflow of the solar wind—a stream of charged particles and magnetic fields emanating from the Sun—that envelops the entire solar system and defines its interaction with the surrounding interstellar medium. This dynamic structure extends outward from the Sun, with its inner regions beginning near the solar corona and encompassing planetary orbits such as Earth's at approximately 1 AU, where the solar influence is prominent.[1] Key characteristics of the heliosphere include its asymmetric, comet-like shape, which arises from the motion of the solar system through the interstellar medium at approximately 26 km/s, creating a rounded "nose" in the direction of travel and an elongated tail in the opposite direction. The heliopause, marking the outer boundary where the solar wind's pressure balances the interstellar medium, lies at approximately 120 AU in the nose direction, with the heliotail extending hundreds to thousands of AU in the opposite direction, resulting in a total volume on the order of 10^{31} km³.[7] Within this region, the plasma density of the solar wind decreases roughly as the inverse square of the distance from the Sun, dropping from around 5 particles per cm³ near Earth to much lower values farther out, while the embedded magnetic fields help maintain the structure's integrity.[8] The heliosphere plays a crucial role in shielding the solar system from galactic cosmic rays (GCRs), high-energy particles originating outside the solar system, by absorbing or deflecting about 75% of them through magnetic field interactions and particle scattering, thereby reducing radiation levels that could otherwise harm planetary atmospheres and surfaces. This protective function modulates space weather events, such as solar storms that propagate through the heliosphere and influence planetary magnetospheres by compressing or eroding them. Additionally, by limiting GCR flux, the heliosphere contributes to astrobiological considerations, potentially fostering conditions more conducive to life by lowering cumulative radiation exposure on habitable worlds.[9][1][10]Formation and Solar Cycle Influence

The heliosphere forms through the continuous outward expansion of the solar wind, a stream of plasma originating from the Sun's corona that carries with it the embedded solar magnetic field, carving out a vast cavity within the surrounding interstellar medium (ISM). This dynamic process creates a protective bubble approximately 100 to 150 astronomical units (AU) in radius, where the solar wind's pressure balances the ram pressure of the incoming ISM, preventing interstellar material from directly penetrating the inner solar system.[1][2] Within this structure, the initially supersonic solar wind gradually slows upon encountering the denser ISM, culminating at the termination shock where it transitions to subsonic flow, thereby establishing layered boundary regions that delineate the heliosphere's internal and external interfaces. Interstellar neutral atoms, primarily hydrogen and helium, freely enter the heliosphere due to their lack of charge, becoming ionized through interactions with solar photons or the solar wind plasma, which then incorporates them into the heliospheric dynamics via magnetic coupling.[1] The heliosphere's extent and properties vary with the approximately 11-year solar cycle, driven by fluctuations in solar activity that alter the solar wind's intensity and the heliospheric magnetic field's strength. During solar maximum, enhanced solar wind speeds and magnetic field intensities cause the heliosphere to expand, reaching up to 10-20% larger dimensions, while it contracts during solar minimum when these parameters weaken. This expansion at solar maximum strengthens the heliosphere's shielding against galactic cosmic rays (GCRs), reducing their flux at Earth by up to 30% through increased scattering and deflection by the intensified magnetic fields.[11][12] The modulation of GCRs can be approximated by the potential , where is the particle charge, is the particle speed, is the magnetic field strength, and the integral is taken along the particle's path through the heliosphere, quantifying the cumulative energy loss due to magnetic interactions.[13] The heliosphere exhibits notable asymmetries, primarily arising from the Sun's rotation, which imprints a spiral structure on the magnetic field (the Parker spiral), and the directional flow of the ISM relative to the Sun, which tilts the overall shape into a comet-like form with an extended tail in the anti-apex direction. These factors combine to distort the boundary surfaces, such as the heliopause, creating north-south and up-down imbalances in the heliosphere's geometry.[14][15]Internal Structure

Solar Wind

The solar wind originates from the Sun's corona, where plasma expands supersonically outward through regions such as coronal holes and streamers.[16] Coronal holes, characterized by low-density, open magnetic field lines, primarily produce the fast solar wind with speeds ranging from 500 to 800 km/s, often emanating from polar regions during solar minimum.[17] In contrast, the slow solar wind, with velocities of 300 to 500 km/s, arises from equatorial streamers and more complex coronal structures associated with closed magnetic fields that intermittently open.[18] The solar wind plasma consists primarily of charged particles, with approximately 95% protons (H⁺), 4% alpha particles (He²⁺), and about 1% trace heavy ions such as carbon, oxygen, and iron, alongside electrons to maintain charge neutrality.[19] At 1 AU from the Sun, the typical proton density is around 5 particles per cm³, with temperatures on the order of 10⁵ K; the density decreases with distance as 1/r² due to the radial expansion of the flow.[16] As the solar wind expands radially, it carries the frozen-in solar magnetic field, which becomes twisted into an Archimedean spiral known as the Parker spiral due to the Sun's 25-day rotation period.[20] The spiral angle θ from the radial direction is given by where Ω is the Sun's angular velocity, r is the heliocentric distance, and V is the solar wind speed; this configuration results in the interplanetary magnetic field lying increasingly azimuthal with distance.[20] Within the heliosphere, the solar wind's plasma flow and embedded magnetic field compress the medium into distinct sectors of alternating polarity (toward or away from the Sun), separated by a warped current sheet that follows the spiral geometry.[21] This dynamic plasma interacts with planetary magnetospheres, driving auroral phenomena on worlds like Earth and Jupiter by channeling energetic particles along magnetic field lines into atmospheric interactions.[22]Heliospheric Magnetic Field and Current Sheet

The interplanetary magnetic field (IMF), also known as the heliospheric magnetic field (HMF), originates from the Sun's corona and is carried outward by the solar wind, forming an Archimedean spiral structure due to the Sun's rotation. At 1 AU, the typical magnitude of the IMF is approximately 5 nT, with the radial component dominating near the Sun and decreasing as , where is the radial field strength at reference distance AU and is the heliocentric distance. This radial component reflects the conservation of magnetic flux in the expanding solar wind, while the azimuthal component decreases more slowly as , leading to an overall field magnitude that scales roughly as at larger distances. The IMF's polarity reverses with the Sun's global dipole field approximately every 11 years during solar maximum, creating a wavy structure in the heliospheric current sheet (HCS) that separates regions of opposite magnetic polarity.[23] The HCS is a thin neutral current sheet, with a thickness of about 10,000 km at 1 AU, embedded within a broader plasma sheet roughly 30 times thicker. It acts as the boundary between the northern and southern hemispheres' opposite-polarity magnetic fields, carrying a small current density of approximately A/m². Due to the tilt of the solar dipole relative to the rotation axis, the HCS warps into a spiral shape as it is carried outward, resembling a "ballerina skirt" that flaps with solar rotation and extends far beyond the planets. Near solar minimum, the sheet aligns closely with the ecliptic plane, forming 2–4 sectors, but it becomes more complex and tilted during solar maximum.[24] Dynamic processes significantly alter the IMF and HCS configuration. Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) propagate through the heliosphere, distorting the ambient magnetic field by compressing and deflecting field lines in three dimensions, particularly when interacting with structured solar wind streams. At the HCS, magnetic reconnection events occur, where oppositely directed fields reconnect, releasing energy and driving plasma jets; these processes accelerate protons to energies up to ~400 keV within the reconnection exhaust, as observed near the Sun.[26][27] The IMF plays a crucial role in particle transport within the heliosphere. Charged cosmic rays are guided along the spiraling field lines, following their gyromotion and drifts, which confines their paths to the large-scale topology of the HMF. This guidance modulates cosmic ray intensities, with the wavy HCS acting as a barrier that scatters and reduces fluxes, particularly during periods of high solar activity when the field is stronger. Additionally, the field influences particle acceleration in the inner heliosphere by providing sites for shock interactions and reconnection, thereby shaping the energy spectra of solar energetic particles.[23][28]Boundary Regions

Termination Shock

The termination shock marks the inner boundary of the heliosphere, where the supersonic solar wind transitions to subsonic flow upon encountering the ram pressure of the local interstellar medium (ISM), resulting in a standing shock wave at distances of approximately 80–100 AU from the Sun.[29] This deceleration occurs as the solar wind's Mach number falls below 1, balancing the outward dynamic pressure of the solar wind with the inward ISM pressure.[7] The shock's position exhibits north-south and nose-tail asymmetry due to variations in solar wind speed and the interstellar magnetic field orientation. In the nose direction (upwind toward the ISM flow), it lies closer to the Sun at about 90 AU, while in the tail direction (downwind), it extends farther to roughly 120 AU.[30] Voyager 1 first crossed the termination shock on December 16, 2004, at a heliocentric distance of 94 AU in the northern hemisphere. Physically, the termination shock converts the solar wind's bulk kinetic energy into thermal energy through dissipative processes, leading to a sharp increase in plasma temperature and density across the shock front. Models predict a post-shock temperature rise to approximately K for pickup ions, though Voyager observations indicate lower thermal plasma temperatures around K, with density compression by a factor of about 4 as dictated by the Rankine-Hugoniot jump conditions for a strong shock.[31][32] These conditions describe the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy, quantifying the shock strength and downstream state. As a key site for diffusive shock acceleration, the termination shock energizes charged particles, contributing to anomalous cosmic rays and serving as the precursor region to the heliopause. Recent multi-fluid simulations incorporating pickup ions and interstellar neutrals have refined the shock's warped, asymmetric shape, incorporating data from Voyager and IBEX to better match observed asymmetries and dynamic responses.[33][29]Heliosheath

The heliosheath is a turbulent region of the heliosphere located between the termination shock and the heliopause, comprising a layer of hot, compressed, subsonic plasma approximately 20–30 AU thick. This layer forms as the solar wind slows and heats upon crossing the termination shock, creating a dynamic environment where plasma flows are deflected and interact with the interstellar medium. Magnetic reconnection is prevalent within the heliosheath, leading to the formation of flux tubes and magnetic structures that contribute to its overall instability.[34][35] Key properties of the heliosheath plasma include a low density of approximately 0.002 particles/cm³ and flow speeds ranging from 100 to 200 km/s, reflecting the subsonic nature post-termination shock. Observations from Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 have detected plasma waves associated with pressure pulses and magnetic bubbles, which are intermittent structures formed by the draping and reconnection of magnetic field lines. These measurements indicate a highly variable plasma environment, with magnetic field strengths reaching up to 0.4 nT—compressed by factors of up to 10 relative to the pre-shock solar wind—enhancing turbulence and particle interactions.[36][37][38] The dynamics of the heliosheath feature turbulence generated from interactions at the termination shock, manifesting as compressive fluctuations and intermittent structures that resemble Voigt profiles in spectral analysis. Recent 2024 studies highlight how this magnetic field compression amplifies turbulence, influencing the entry and modulation of galactic cosmic rays (GCRs) by trapping and scattering them within the region. As a buffer zone, the heliosheath protects the inner heliosphere from interstellar particles while serving as a primary site for the production of energetic neutral atoms (ENAs) through charge exchange between hot plasma ions and interstellar neutrals.[39][40][41]Heliopause

The heliopause serves as the contact discontinuity that demarcates the boundary between the plasma of the heliosheath and the local interstellar medium (ISM), situated at an average distance of approximately 120 AU from the Sun. This interface represents the outermost extent of the Sun's magnetic influence, where the solar wind's dynamic pressure transitions to that of the incoming interstellar flow. The structure is relatively thin, with a thickness on the order of km, though observations suggest it may encompass a broader boundary layer in some regions due to magnetic reconnection processes.[42][43] At the heliopause, the interstellar magnetic field drapes over the boundary, resulting in a pile-up of field lines on the solar side and a reconfiguration that enhances magnetic pressure. This draping maintains an approximate pressure balance, where the total pressure from the heliosheath plasma and magnetic field () equilibrates with that of the ISM (), primarily through contributions from thermal plasma, magnetic fields, and cosmic ray pressures. The balance is dynamic, influenced by the relative velocities and densities of the interacting flows, with the interstellar field orientation playing a key role in shaping the interface.[44][45][46] The crossing of the heliopause by Voyager 1 on August 25, 2012, at a heliocentric distance of 121 AU, and by Voyager 2 on November 5, 2018, at approximately 119 AU, provided the first direct in situ measurements of this boundary, revealing an influx of cooler ISM plasma with temperatures around 30,000–50,000 K and electron densities of 0.05–0.14 particles per cubic centimeter.[47] Despite these elevated temperatures, a spacecraft can pass through the plasma layer at the heliopause without thermal damage due to the extremely low plasma density, which results in negligible heat transfer via rare particle collisions; both Voyager spacecraft continued to operate and transmit data afterward.[48] Instruments aboard the spacecraft detected a sharp transition, including the depletion of solar-originated energetic particles and the onset of interstellar plasma signatures, confirming the boundary's role as a plasma separator. The heliopause exhibits structural asymmetry, appearing thinner in the nose region—where the interstellar flow directly impinges—compared to the thicker configuration along the flanks, due to varying compression and flow deflection. Recent 2025 models incorporating pickup ions, formed from charge exchange between interstellar neutrals and solar plasma, enhance understanding of the boundary's stability by accounting for their contributions to pressure and wave-driven fluctuations outside the heliopause.[49][50] Crossing the heliopause signifies entry into local interstellar space, beyond the dominant influence of the solar wind, with immediate observational signatures including a precipitous drop in solar particle fluxes and a corresponding rise in galactic cosmic rays (GCRs), which are no longer significantly modulated by the heliospheric magnetic field. This transition underscores the heliopause's function as a shield against external cosmic radiation, protecting the inner solar system.Heliotail

The heliotail is the elongated, downstream extension of the heliosphere beyond the heliopause, resembling a cometary tail that stretches for thousands of astronomical units (AU) in the direction opposite to the Sun's motion through the interstellar medium (ISM).[51] This structure forms as solar wind plasma is draped and compressed by the oncoming ISM flow, creating a narrow, collimated region with an opening angle of approximately 30°–60° due to the draping of magnetic fields and plasma dynamics.[52] Within the heliotail, magnetic reconnection between the interstellar magnetic field (BISM) and solar wind magnetic field (BSW) generates flux tubes and polarity domains, forming pathways akin to a "magnetic highway" that facilitate the transport of charged particles along field lines.[53] Dynamically, the heliotail exhibits complex plasma behavior shaped by interactions with the ISM. NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft, after crossing the heliopause in 2012, began detecting signatures of the outer heliosphere, including accelerated electrons in the form of bursty emissions indicative of ongoing acceleration processes near the boundary.[54] Recent magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations from 2025 reveal that the heliotail extends beyond 1000 AU, with its length and stability influenced by the pressure of the interstellar magnetic field, which compresses and orients the tail along the interstellar flow direction.[7] Key properties of the heliotail include a plasma density significantly lower than that in the upstream heliosheath—typically around 0.005 cm−3 compared to higher values near the termination shock—due to expansion and rarefaction in the downstream flow.[53] This region also features elevated levels of turbulence, driven by instabilities in the sheared plasma flows and magnetic reconnection events, resulting in strong, nonlinear convective processes that dominate over viscous damping.[55] The heliotail's magnetic structure plays a crucial role in channeling galactic cosmic rays (GCRs) back toward the Sun, as the alternating polarity domains within the 100–300 AU-wide flux tubes scatter and redirect high-energy particles through stochastic reconnection.[56] Advancements in MHD modeling from 2023 to 2025 have provided deeper insights into the heliotail's morphology, depicting it as a twisted, lobe-like structure with high-latitude inclinations influenced by the draped interstellar field.[57] These models incorporate time-dependent solar wind variations, showing that the 11-year solar cycle modulates the tail's coherence by altering plasma injection and magnetic flux transport, leading to periodic changes in collimation and turbulence intensity.[58]Interstellar Interactions

Hydrogen Wall

The hydrogen wall is a region of enhanced density of interstellar neutral hydrogen atoms located immediately outside the heliopause, resulting from interactions between the inflowing interstellar medium and the heliospheric plasma. This structure forms as neutral hydrogen atoms from the local interstellar medium (LISM) slow down and accumulate due to charge exchange reactions with hot protons in the outer heliosheath. These reactions transfer momentum from the plasma to the neutrals, causing a pile-up where the hydrogen density increases by approximately a factor of 5 compared to the unperturbed LISM value.[59] Positioned about 0.5–1 AU beyond the heliopause, which lies at roughly 120 AU from the Sun, the hydrogen wall manifests as a narrow layer detectable through its effects on ultraviolet light. The piled-up hydrogen atoms scatter incoming solar Lyman-α radiation (at 121.6 nm), producing a characteristic glow that can be observed remotely. This scattering enables mapping of the wall's structure via measurements of the Lyman-α intensity, with the column density of hydrogen given by the line-of-sight integral , where is the local neutral density and is the path length element; higher values indicate the density enhancement.[60] Observations from the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission, launched in 2008, have provided key insights into the hydrogen wall since 2009 by detecting energetic neutral atoms (ENAs) generated through charge exchange in this region. These ENAs, produced when heliosheath protons interact with the dense neutral hydrogen, allow indirect imaging of the wall's location and extent from 1 AU. The hydrogen wall serves as a probe of LISM properties, such as neutral density and flow velocity, and influences ENA production by providing a reservoir of target atoms for secondary neutral creation. Recent 2024 studies have connected the wall's dynamics to the broader context of the Local Bubble, suggesting that the solar system's passage through its edge modulates heliospheric size and neutral interactions.[59][61]Bow Wave

The bow wave of the heliosphere forms as the solar system moves through the local interstellar medium (LISM) at a relative velocity of approximately 26 km/s, compressing the ISM into a bow-like structure at roughly 250 to 350 AU from the Sun in the upstream direction. This compression region, often modeled at around 300 AU in the upstream direction, arises from the heliosphere acting as an obstacle to the oncoming interstellar flow, diverting and slowing the plasma without generating a discontinuous shock front.[62][63] The subsonic nature of the LISM flow, characterized by a magnetosonic Mach number of about 0.7 to 1, precludes the formation of a traditional bow shock, resulting instead in a broad, continuous bow wave. This wave is further intensified by the draping of the interstellar magnetic field lines around the heliosphere, which adds magnetic pressure to the compression and shapes the plasma deflection.[64][65][7] Observational evidence from NASA's Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission, which maps energetic neutral atoms from the heliosphere's boundaries, reveals a slowdown in interstellar plasma velocities consistent with wave-mediated compression rather than abrupt shocking. Complementary Voyager measurements of enhanced interstellar magnetic fields further support this, indicating insufficient flow speed for a shock. Research from 2023 to 2025, including analyses of IBEX data and NASA Scientific Visualization Studio models, has solidified the consensus against a bow shock, predicting the wave's location at approximately 300 AU based on multi-fluid simulations.[64][62][66] This structure profoundly influences the dynamics of the local ISM by redirecting plasma flows around the heliosphere, creating an asymmetric envelope that affects the influx and trajectory of galactic cosmic rays into the inner solar system. In theoretical models, the strength and extent of the bow wave are quantified using the plasma β parameter, defined as the ratio of thermal gas pressure to magnetic pressure (β = P_gas / P_mag), which determines the balance between hydrodynamic and magnetohydrodynamic effects in the compression layer.[67][65]Observations and Detection

Spacecraft Missions

The Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft, launched in March 1972 and April 1973, respectively, conducted the earliest in-situ measurements of the solar wind in the outer heliosphere. Equipped with plasma instruments, they recorded solar wind parameters such as velocity and density out to heliocentric distances of approximately 50 AU, revealing the gradual slowing and cooling of the solar wind with increasing distance from the Sun.[68] These observations provided foundational data on the large-scale structure of the solar wind before the termination shock, demonstrating its persistence and variability over decades of flight.[69] The Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, launched in September and August 1977, have delivered the most detailed in-situ probes of the heliosphere's outer boundaries to date. Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock on December 16, 2004, at a distance of 94 AU, entering the heliosheath where solar wind speeds dropped from supersonic to subsonic levels.[42] Voyager 2 followed, crossing the termination shock on August 30, 2007, at 84 AU, confirming the shock's location and properties in a different directional sector.[42] Voyager 1 reached the heliopause on August 25, 2012, at 122 AU, while Voyager 2 crossed it on November 5, 2018, at 119 AU; both transitions were marked by a sharp increase in galactic cosmic ray flux—by about 10% for Voyager 2—and a tenfold drop in plasma density, signaling the shift from heliospheric to interstellar plasma. Despite the high plasma temperatures of approximately 30,000–50,000 Kelvin in the plasma layer at the heliopause, both spacecraft passed through without thermal damage due to the extremely low plasma density (electron densities of 0.06–0.15 particles per cubic centimeter), which results in negligible heat transfer via rare particle collisions; for details on heliopause plasma properties, see the "Heliopause" section.[42][47] Voyager 1 has since entered the heliotail, measuring compressed magnetic fields and low plasma densities consistent with the heliosphere's downwind extension.[30] The Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX), launched in October 2008, employs energetic neutral atom (ENA) imaging to provide global, remote views of the heliosphere's outer regions without direct spacecraft passage. By detecting ENAs produced through charge-exchange in the heliosheath and beyond, IBEX has mapped the structure of the heliosheath, revealing its dynamic response to solar wind variations, and imaged the hydrogen wall—a layer of compressed interstellar neutral hydrogen atoms just outside the heliopause.[59] Observations spanning over a solar cycle have shown time-varying ENA fluxes that trace plasma pressures and flows in the heliosheath.[14] Data from 2023 to 2025, incorporating extended mission observations, have further refined models of the heliopause's asymmetry, highlighting oblique and rippled structures influenced by the interstellar magnetic field.[14] More recently, the Parker Solar Probe, launched in August 2018, has focused on the inner heliosphere, measuring magnetic fields close to the Sun to understand their evolution into the broader heliospheric structure. Its FIELDS instrument has captured high-resolution data on magnetic turbulence, switchbacks, and the heliospheric current sheet during close solar approaches as near as 0.17 AU, linking coronal origins to outer heliosphere dynamics.[70] Complementing these, the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP), launched on September 24, 2025, is designed for advanced ENA imaging of the heliosphere's boundaries from the Sun-Earth L1 point, with its suite of 10 instruments expected to deliver first high-fidelity maps in 2026, building on IBEX to resolve particle acceleration and global asymmetries at unprecedented resolution.[71] During its primary mission phase in the 2000s, NASA's Cassini spacecraft, orbiting Saturn from 2004 to 2017, used its Ion and Neutral Camera (INCA) to observe ENAs originating from the outer heliosphere. These remote measurements from ~10 AU revealed large-scale structures in the heliosheath, including azimuthal variations in ENA flux that trace the global distribution of solar wind plasma and its interaction with the interstellar medium, providing early evidence of the heliosphere's non-spherical shape.[72]Remote and Local Methods

Energetic neutral atom (ENA) imaging provides a remote diagnostic of the heliosphere's boundaries by detecting charge-exchanged atoms originating from the inner heliosheath, where solar wind ions interact with interstellar neutrals. The Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission has produced all-sky maps of ENAs in the 0.1–6 keV range, revealing structures such as the ribbon—a narrow band of enhanced flux—and global emissions that trace the heliopause and termination shock.[59] Similarly, the Ion Neutral Camera (INCA) on Cassini has imaged ENAs in the 5–200 keV range, showing asymmetric intensities that delineate the heliosphere's interaction with the local interstellar medium (LISM). Recent analyses of IBEX data from 2024 have identified enhanced ENA fluxes in the heliotail, indicating structured plasma flows and magnetic field draping in the downwind region beyond 100 AU.[57] Cosmic ray modulation serves as an indirect probe of heliospheric structure, as galactic cosmic rays (GCRs) are scattered and attenuated by solar wind magnetic fields and the heliospheric current sheet (HCS). Ground-based neutron monitors, such as those in the global network, record secondary neutrons produced by GCR interactions in Earth's atmosphere, revealing flux variations tied to the 11-year solar cycle, with minima during solar maximum due to increased magnetic turbulence.[73] The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer-02 (AMS-02) on the International Space Station measures GCR protons and helium nuclei directly above the atmosphere, confirming spectral hardening at rigidities around 200 GV and drift effects across polarity cycles. Forbush decreases—sharp, transient drops in GCR intensity—signal crossings of the HCS or interplanetary coronal mass ejections, providing snapshots of heliospheric compression and diffusion barriers.[74] Ultraviolet spectroscopy of Lyman-α emission and absorption maps the neutral hydrogen distribution at the heliosphere's edge, particularly the hydrogen wall formed by charge exchange between interstellar hydrogen and solar wind protons. Observations from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) have detected redshifted Lyman-α absorption toward nearby stars, confirming a hydrogen wall density enhancement of about 1.5–2 atoms cm⁻³ at the heliopause.[75] Ground-based telescopes, such as those using high-resolution spectrographs, complement HST by resolving Doppler-shifted backscattered solar Lyman-α photons, which trace the wall's geometry and its response to solar cycle variations in the ionization cavity.[60] Local detection methods leverage Earth's magnetosphere as a natural laboratory for heliospheric influences, capturing solar wind and pickup ions that interact with geomagnetic fields. The Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms (THEMIS) mission observes plasma entry through the magnetopause, revealing how heliospheric suprathermal ions modulate auroral substorms and ring current dynamics.[76] The Cluster mission, with its multi-spacecraft configuration, measures three-dimensional current systems and wave-particle interactions at the bow shock, linking heliospheric turbulence to magnetospheric responses like ULF waves.[76] The synergy among the heliophysics fleet enhances remote sensing of heliospheric features, such as the current sheet. Launched in 2020, Solar Orbiter's Remote Sensing Instruments, including the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) and Solar Orbiter Heliospheric Imager (SoloHI), observe coronal mass ejections and HCS warp from high latitudes, correlating white-light densities with in-situ magnetic field reversals to model sheet evolution out to 1 AU.[77] This integration with missions like Parker Solar Probe validates remote proxies against local measurements, refining global heliospheric models.[77]Historical Development

Theoretical Foundations

As early as 1951, Ludwig Biermann proposed a continuous stream of solar corpuscular radiation to explain the anti-solar orientation of comet tails, laying groundwork for later models.[78] In the 1950s, early theoretical ideas about the heliosphere drew analogies from comet tails to conceptualize the interaction between solar plasma and the surrounding interstellar medium (ISM). Hannes Alfvén proposed that the plasma tails of comets are sculpted by a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun, akin to a solar corpuscular wind that would carve out a plasma cavity in the ISM, foreshadowing the heliosphere's structure.[79] This analogy highlighted the dynamic interplay between solar outflows and neutral interstellar gas, setting the stage for more quantitative models. Building on these ideas, Eugene Parker in the late 1950s formulated the modern concept of the solar wind as a continuous, supersonic expansion of ionized gas from the hot solar corona, inherently predicting the formation of a low-density cavity—the heliosphere—embedded within the denser ISM.[80] Parker's subsequent 1961 isothermal model refined this by solving the steady-state hydrodynamic equations for an isothermal corona, demonstrating how thermal pressure drives the flow from subsonic speeds near the Sun to supersonic velocities at a critical radius of about 5–10 solar radii, establishing the expansive nature of the heliospheric bubble.[81] During the 1970s, magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations advanced these foundations by incorporating magnetic fields and plasma dynamics to delineate the heliosphere's boundaries. Researchers like S. T. Suess developed models that simulated the solar wind's interaction with the ISM, predicting key structural features such as the termination shock at approximately 100 AU, where the supersonic solar wind decelerates to subsonic speeds, and the warping of the heliospheric current sheet due to the tilted solar magnetic dipole, creating a wavy, ballerina-skirt-like configuration.[82] These models also anticipated the heliosphere's role in cosmic ray shielding through diffusive transport, governed by Parker's equation: where is the cosmic ray distribution function, is the diffusion tensor, and represents sources or sinks; this framework illustrated how magnetic irregularities within the heliosphere scatter and reduce incoming galactic cosmic ray fluxes. A notable debate in early heliospheric theory centered on the nature of the upstream boundary with the ISM, with initial models assuming a sharp bow shock analogous to planetary magnetospheres, but skepticism emerged over whether the relatively low ISM density could sustain such a discontinuity. This was resolved in the 2010s through advanced MHD simulations, which favored a gentler bow wave over a traditional shock, consistent with the observed neutral hydrogen flow and magnetic field draping around the heliopause.Key Discoveries and Timeline