Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mauthausen concentration camp

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

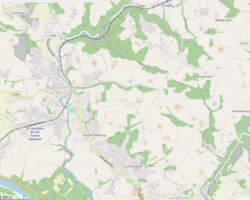

Mauthausen was a Nazi concentration camp on a hill above the market town of Mauthausen (roughly 20 kilometres (12 mi) east of Linz) in Upper Austria. It was the main camp of a group with nearly 100 further subcamps located throughout Austria and southern Germany.[2][3][4]

The three Gusen concentration camps in and around the village of St. Georgen/Gusen, just a few kilometres from Mauthausen, held a significant proportion of prisoners within the camp complex, at times exceeding the number of prisoners at the Mauthausen main camp.[2][5][6]

The Mauthausen main camp operated from 8 August 1938, several months after the German annexation of Austria, to 5 May 1945, when it was liberated by the United States Army.[5][7][8] Starting with the camp at Mauthausen, the number of subcamps expanded over time. In January 1945, the camps contained roughly 85,000 inmates.[2][7][9]

As at other Nazi concentration camps, the inmates at Mauthausen and its subcamps were forced to work as slave labour, under conditions that caused many deaths. Mauthausen and its subcamps included quarries, munitions factories, mines, arms factories and plants assembling Me 262 fighter aircraft.[6][10][11] The conditions at Mauthausen were even more severe than at most other Nazi concentration camps.[7][8][9] Half of the 190,000 inmates died at Mauthausen or its subcamps.[12][13]

Mauthausen was one of the first massive concentration camp complexes in Nazi Germany, and the last to be liberated by the Allies.[14][15][16] The Mauthausen main camp is now a museum.[15][17][18]

Establishment of the main camp

[edit]

On 9 August 1938, prisoners from Dachau concentration camp near Munich were sent to the town of Mauthausen in Austria, to begin building a new slave labour camp.[19] The site was chosen because of the nearby granite quarry and its proximity to Linz.[20][21] Although the camp was controlled by the German state from the beginning, it was founded by a private company as an economic enterprise.[21]

The owner of the Wiener-Graben quarry (the Marbacher-Bruch and Bettelberg quarries) was a DEST (Deutsche Erd– und Steinwerke GmbH) company.[22] The company was led by Oswald Pohl, who was a high-ranking official of the Schutzstaffel (SS).[23] It rented the quarries from the City of Vienna in 1938 and started the construction of the Mauthausen camp.[10] A year later, the company ordered the construction of the first camp at Gusen.

The granite mined in the quarries had previously been used to pave the streets of Vienna, but Nazi authorities envisioned a complete reconstruction of major German towns in accordance with the plans of Albert Speer and other proponents of Nazi architecture,[24] for which large quantities of granite were needed.[21] The money to fund the construction of the Mauthausen camp was gathered from a variety of sources, including commercial loans from Dresdner Bank and Prague-based Böhmische Escompte-Bank; the so-called Reinhardt's fund (meaning money stolen from the inmates of the concentration camps themselves); and from the German Red Cross.[20][note 1]

Mauthausen initially served as a strictly-run prison camp for common criminals, prostitutes,[25] and other categories of "Incorrigible Law Offenders".[note 2] On 8 May 1939 it was converted to a labour camp for political prisoners.[27]

Gusen

[edit]The three Gusen concentration camps held a significant proportion of prisoners within the Mauthausen-Gusen complex. For most of its history, this exceeded the number of prisoners at the Mauthausen main camp itself.[28]

DEST began purchasing land at Sankt Georgen an der Gusen in May 1938. During 1938 and 1939, inmates of the nearby Mauthausen makeshift camp marched daily to the granite quarries at St Georgen/Gusen, which were more productive and more important for DEST than the Wienergraben Quarry.[10] After the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, the as-yet unfinished Mauthausen camp became overcrowded with prisoners. The number of inmates rose from 1,080 in late 1938 to over 3,000 a year later.[29][30] At about that time, the construction of a new camp "for the Poles" began in Gusen (Langenstein) about 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi) away after an order by the SS (Schutzstaffel) in December 1939.[31] The new camp (later named Gusen I) became operational in May 1940. The first inmates were put in the first two huts (No. 7 and 8) on 17 April 1940,[32] while the first transport of prisoners – mostly from the camps in Dachau and Sachsenhausen – arrived just over a month later, on 25 May.[33]

Like nearby Mauthausen, the Gusen camps also rented inmates out to various local businesses as slave labour. In October 1941, several huts were separated from the Gusen subcamp by barbed wire and turned into a separate Prisoner of War Labour Camp (German: Kriegsgefangenenarbeitslager).[34][35] This camp had many prisoners of war, mostly Red Army officers.[36][35] By 1942 the production capacity of Mauthausen and the Gusen camps had reached its peak. The Gusen site was expanded to include the central depot of the SS, where various goods seized from occupied territories were sorted and then dispatched to Germany.[37] Local quarries and businesses were in constant need of a new source of labour because more and more Austrians were drafted into the Wehrmacht.[38]

In March 1944, the former SS depot was converted to a new subcamp named Gusen II, which served as an improvised concentration camp until the end of the war. Gusen II contained 12,000 to 17,000 inmates, deprived of even the most basic facilities.[3] In December 1944, Gusen III was opened in nearby Lungitz. Here, parts of a factory infrastructure were converted into the third Gusen camp.[3] The increasing number of subcamps could not keep up with the rising number of inmates, which led to overcrowding of the huts in Mauthausen and its subcamps. From late 1940 to 1944, the number of inmates per bed rose from two to four.[3]

Subcamps

[edit]

As production in Mauthausen and its subcamps constantly increased, so too did the number of detainees and subcamps. Initially the camps at Gusen and Mauthausen mostly served the local quarries, from 1942 onwards they began to be included in the German war machine. To accommodate the ever-growing number of slave workers, additional subcamps (German: Außenlager) of Mauthausen were built.

By the end of the war, the list included 101 camps (including 49 major subcamps)[39] which covered most of modern Austria, from Mittersill south of Salzburg to Schwechat east of Vienna and from Passau on the prewar Austro-German border to the Loibl Pass on the border with Yugoslavia. The subcamps were divided into several categories, depending on their main function: Produktionslager for factory workers, Baulager for construction, Aufräumlager for cleaning the rubble in Allied-bombed towns, and Kleinlager (small camps) where the inmates worked specifically for the SS.[citation needed]

Forced labour

[edit]Business enterprise

[edit]

The production output of Mauthausen and its subcamps exceeded that of each of the five other large slave labour centres: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Flossenbürg, Gross-Rosen, Marburg and Natzweiler-Struthof, in terms of both production quota and profits.[40] The list of companies using slave labour from Mauthausen and its subcamps was long, and included both national corporations and small, local firms and communities. Some parts of the quarries were converted into a Mauser machine pistol assembly plant.

In 1943, an underground factory for the Steyr-Daimler-Puch company was built in Gusen. Altogether, 45 larger companies took part in making Mauthausen and its subcamps one of the most profitable concentration camps of Nazi Germany, with more than 11,000,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁ in profits in 1944 alone (EUR 86.7 million in 2021).[note 3] The companies using slave labourers from Mauthausen included:[40]

- DEST cartel (producing bricks and quarrying stone for German state construction projects)

- Accumulatoren-Fabrik AFA (the main producer of batteries for German U-boats)

- Bayer (the main German producer of medicines and medications)

- Deutsche Bergwerks- und Hüttenbau (constructing mines and quarries)

- Linz-based Eisenwerke Oberdonau (the largest World War II steel supplier for the German Panzer tanks)[43]

- Flugmotorenwerke Ostmark (aeroplane engine manufacturer)

- Nibelungenwerk (the largest tank factory in Nazi Germany)

- Otto Eberhard Patronenfabrik (munitions works)

- Heinkel and Messerschmitt (Heinkel-Sud facilities in Floridsdorf, Vienna-Schwechat and Zwölfaxing, and other aeroplane factories, also a V-2 rocket factory)

- Österreichische Sauerwerks (arms producer)

- Rax-Werke (machinery and V-2 rockets)

- Steyr-Daimler-Puch (arms and vehicles)

- Hochtief (construction of tunnels in the Loibl Pass)

Prisoners were also rented out as slave labour to work on local farms, road construction, reinforcing and repairing the banks of the Danube, constructing large residential areas in Sankt Georgen,[10] and excavating archaeological sites in Spielberg.[citation needed]

When the Allied strategic bombing campaign started to target the German war industry, German planners decided to move production to underground facilities that were impenetrable to enemy aerial bombardment. In Gusen I, the prisoners were ordered to build several large tunnels beneath the hills surrounding the camp (code-named Kellerbau). By the end of World War II the prisoners had dug 29,400 square metres (316,000 sq ft) to house a small-arms factory.

In January 1944, similar tunnels were also built beneath the village of Sankt Georgen by the inmates of Gusen II subcamp (code-named Bergkristall).[44] They dug roughly 50,000 square metres (540,000 sq ft) so the Messerschmitt company could build an assembly plant to produce the Messerschmitt Me 262 and V-2 rockets.[45] In addition to planes, some 7,000 square metres (75,000 sq ft) of Gusen II tunnels served as factories for various war materials.[10][46] In late 1944, roughly 11,000 of the Gusen I and II inmates were working in underground facilities.[47] An additional 6,500 worked on expanding the underground network of tunnels and halls.

In 1945, the Me 262 works was already finished and the Germans were able to assemble 1,250 planes a month.[10][note 4] This was the second largest plane factory in Germany after the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, which was also underground.[47]

Weapons research

[edit]In January 2015, a "panel of archaeologists, historians and other experts" ruled out the earlier claims of an Austrian filmmaker that a bunker underneath the camp was connected to the German nuclear weapon project.[49] The panel indicated that stairs uncovered during an excavation prompted by the allegations led to an SS shooting range.[49]

Extermination

[edit]

The political function of the camp continued in parallel with its economic role. Until at least 1942, it was used for the imprisonment and murder of the Nazis' political and ideological enemies, real and imagined.[4][50] Initially, the camp did not have a gas chamber of its own and the so-called Muselmänner, or prisoners who were too sick to work, after being maltreated, under-nourished or exhausted, were then transferred to other concentration camps for extermination (mostly to the Hartheim Euthanasia Centre,[51] which was 40.7 kilometres or 25.3 miles away), or killed by lethal injection and cremated in the local crematorium. The growing number of prisoners made this system too expensive and from 1940, Mauthausen was one of the few camps in the West to use a gas chamber on a regular basis. In the beginning, an improvised mobile gas chamber – a van with the exhaust pipe connected to the inside – shuttled between Mauthausen and Gusen.[52] It was capable of killing about 120 prisoners at a time when it was completed.[53][54]

Inmates

[edit]

Until early 1940, the largest group of inmates consisted of German, Austrian and Czechoslovak socialists, communists, homosexuals, anarchists and people of Romani origin.[citation needed] Other groups of people to be persecuted solely on religious grounds were the Sectarians, as they were dubbed by the Nazi regime, meaning Bible Students, or as they are called today, Jehovah's Witnesses. The reason for their imprisonment was their rejection of giving the loyalty oath to Hitler and their refusal to participate in any kind of military service.[27]

In early 1940, many Poles were transferred to the Mauthausen–Gusen complex. The first groups were mostly composed of artists, scientists, Boy Scouts, teachers, and university professors,[20][55] who were arrested during Intelligenzaktion and the course of the AB Action.[56] Camp Gusen II was called by Germans Vernichtungslager für die polnische Intelligenz ("Extermination camp for the Polish intelligentsia").[57]

Later in the war, new arrivals were from every category of the "unwanted", but educated people and so-called political prisoners constituted the largest part of all inmates until the end of the war. During World War II, large groups of Spanish Republicans were also transferred to Mauthausen and its subcamps.[58] Most of them were former Republican soldiers or activists who had fled to France after Francisco Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War and then were captured by German forces after the defeat of France in 1940 or handed over to the Germans by the Vichy authorities. The largest of these groups arrived at Gusen in January 1941.[59] On 24 August 1940, a cattle train from Angoulême with 927 Spanish refugees onboard arrived at Mauthausen. The group believed that they were being taken to Vichy. Of the 490 males, those over the age of 13 were separated from their families and taken to the extermination camp nearby. 357 of the 490 would die in the camp. The remaining women and children were then sent back to Spain.[58]

In early 1941, almost all the Poles and Spaniards, except for a small group of specialists working in the quarry's stone mill, were transferred from Mauthausen to Gusen.[48] Following the outbreak of the Soviet-German War in 1941, the camps started to receive a large number of Soviet POWs. Most of them were kept in huts separated from the rest of the camp. The Soviet prisoners of war were a major part of the first groups to be gassed in the newly built gas chamber in early 1942. In 1944, a large group of Hungarian and Dutch Jews, about 8,000 people altogether, was also transferred to the camp. Much like all the other large groups of prisoners that were transferred to Mauthausen and its subcamps, most of them either died as a result of the hard labour and poor conditions, or were deliberately killed.[citation needed]

After the Nazi invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941 and the outbreak of the partisan resistance in summer of the same year, many people suspected of aiding the Yugoslav resistance were sent to the Mauthausen camp, mostly from areas under direct German occupation, namely northern Slovenia and Serbia. An estimated 1,500 Slovenes died in Mauthausen.[60]

Throughout the years of World War II, the Mauthausen and its subcamps received new prisoners in smaller transports daily, mostly from other concentration camps in German-occupied Europe. Most of the prisoners at the subcamps of Mauthausen had been kept in a number of different detention sites before they arrived. The most notable of such centres for Mauthausen and its subcamps were the camps at Dachau and Auschwitz. The first transports from Auschwitz arrived in February 1942. The second transport in June of that year was much larger and numbered some 1,200 prisoners. Similar groups were sent from Auschwitz to Gusen and Mauthausen in April and November 1943, and then in January and February 1944. Finally, after Adolf Eichmann visited Mauthausen in May of that year, Mauthausen received the first group of roughly 8,000 Hungarian Jews from Auschwitz; the first group to be evacuated from that camp before the Soviet advance. Initially, the groups evacuated from Auschwitz consisted of qualified workers for the ever-growing industry of Mauthausen and its subcamps, but as the evacuation proceeded other categories of people were also transported to Mauthausen, Gusen, Vienna or Melk.[citation needed]

| Subcamp inmate counts Late 1944 – early 1945[20][note 5] | |

|---|---|

| Gusen I, II, III | 26,311 |

| Ebensee | 18,437 |

| Gunskirchen | 15,000 |

| Melk | 10,314 |

| Linz | 6,690 |

| Amstetten | 2,966 |

| Wiener-Neudorf | 2,954 |

| Schwechat | 2,568 |

| Steyr-Münichholz | 1,971 |

| Schlier-Redl-Zipf | 1,488 |

Over time, Auschwitz had to almost stop accepting new prisoners and most were directed to Mauthausen instead. The last group – roughly 10,000 prisoners – was evacuated in the last wave in January 1945, only a few weeks before the Soviet liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex.[61] Among them was a large group of civilians arrested by the Germans after the failure of the Warsaw Uprising,[62][35] but by the liberation not more than 500 of them were still alive.[63] Altogether, during the final months of the war, 23,364 prisoners from other concentration camps arrived at the camp complex.[63] Many more perished from exhaustion during death marches, or in railway wagons, where the prisoners were confined at sub-zero temperatures for several days before their arrival, without adequate food or water. Prisoner transports were considered less important than other important services, and could be kept on sidings for days as other trains passed.[citation needed]

Many of those who survived the journey died before they could be registered, whilst others were given the camp numbers of prisoners who had already been killed.[63] Most were then accommodated in the camps or in the newly established tent camp (German: Zeltlager) just outside the Mauthausen subcamp, where roughly 2,000 people were forced into tents intended for not more than 800 inmates, and then starved to death.[64]

As in all other Nazi concentration camps, not all the prisoners were equal. Their treatment depended largely on the category assigned to each inmate, as well as their nationality and rank within the system. The so-called kapos, or prisoners who had been recruited by their captors to police their fellow prisoners, were given more food and higher pay in the form of concentration camp coupons which could be exchanged for cigarettes in the canteen, as well as a separate room inside most barracks.[65] On Himmler's order of June 1941, a brothel was opened in the Mauthausen and Gusen I camps in 1942.[66][67] The Kapos formed the main part of the so-called Prominents (German: Prominenz), or prisoners who were given a much better treatment than the average inmate.[68]

"If there is a God, he will have to beg my forgiveness."

Women and children in Mauthausen

[edit]

Although the Mauthausen camp complex was mostly a labour camp for men, a women's camp was opened in Mauthausen, in September 1944, with the first transport of female prisoners from Auschwitz. Eventually, more women and children came to Mauthausen from Ravensbrück, Bergen-Belsen, Gross-Rosen, and Buchenwald. Along with the female prisoners came some female guards; 20 are known to have served in the Mauthausen camp, and 60 in the whole camp complex. Holocaust Survivor, Eva Clarke was born at the camp and liberated 3-weeks later by Eisenhower's US army Forces.[70]

Female guards also staffed the Mauthausen subcamps at Hirtenberg, Lenzing (the main women's subcamp in Austria), and Sankt Lambrecht. The Chief Overseers at Mauthausen were firstly Margarete Freinberger, and then Jane Bernigau. Almost all the female Overseers who served in Mauthausen were recruited from Austrian cities and towns between September and November 1944. In early April 1945, at least 2,500 more female prisoners came from the female subcamps at Amstetten, St. Lambrecht, Hirtenberg, and the Flossenbürg subcamp at Freiberg. According to Daniel Patrick Brown, Hildegard Lächert also served at Mauthausen.[71]

The available Mauthausen inmate statistics from the spring of 1943, shows that there were 2,400 prisoners below the age of 20, which was 12.8% of the 18,655 population. By late March 1945, the number of juvenile prisoners in Mauthausen increased to 15,048, which was 19.1% of the 78,547 Mauthausen inmates. The number of imprisoned children increased 6.2 times, whereas the total number of adult prisoners during the same period multiplied by a factor of only four.[72]

These numbers reflected the increasing use of Polish, Czech, Soviet, and Balkan teenagers as slave labour as the war continued.[73] Statistics showing the composition of juvenile inmates shortly before their liberation reveal the following major child/prisoner sub-groups: 5,809 foreign civilian labourers, 5,055 political prisoners, 3,654 Jews, and 330 Russian POWs. There were also 23 Romani children, 20 so-called "anti-social elements", six Spaniards, and three Jehovah's Witnesses.[72]

Treatment of inmates and methodology of crime

[edit]Mauthausen was one of the most brutal and severe of the Nazi concentration camps;[74][75][76] prisoners at Dachau considered themselves fortunate to be not at a death camp like Mauthausen.[77] Inmates suffered not only from malnutrition, overcrowded huts and constant abuse and beatings by the guards and kapos,[48] but also from exceptionally hard labour.[53]

The work in the quarries – often in unbearable heat or in temperatures as low as −30 °C (−22 °F)[48] – led to exceptionally high mortality rates.[75][note 6] The food rations were limited, and during the 1940–1942 period, an average inmate weighed 40 kilograms (88 lb).[78] It is estimated that the average energy content of food rations dropped from about 1,750 calories (7,300 kJ) a day during the 1940–1942 period, to between 1,150 and 1,460 calories (4,800 and 6,100 kJ) a day during the next period. In 1945 the energy content was even lower and did not exceed 600 to 1,000 calories (2,500 to 4,200 kJ) a day – less than a third of the energy needed by an average worker in heavy industry.[3] The reduced rations led to the starvation of thousands of inmates.

The rock quarry in Mauthausen was at the base of the "Stairs of Death". Prisoners were forced to carry roughly-hewn blocks of stone – often weighing as much as 50 kilograms (110 lb) – up the 186 stairs, one prisoner behind the other. As a result, many exhausted prisoners collapsed in front of the other prisoners in the line, and then fell on top of the other prisoners, creating a domino effect; the first prisoner falling onto the next, and so on, all the way down the stairs.[79] In the quarry, prisoners were forced to carry the boulders from morning until night, whipped by Nazi guards.[80][81]

The inmates of Mauthausen, Gusen I, and Gusen II had access to a separate part of the camp for the sick – the so-called Krankenlager. Despite the fact that (roughly) 100 medics from among the inmates were working there,[82] they were not given any medication and could offer only basic first aid.[20][82] Thus the hospital camp – as it was called by the German authorities – was, in fact, a "hospital" only in name.

Such brutality was not accidental. Former prisoner Edward Mosberg said: "If you stopped for a moment, the SS either shot you or pushed you off the cliff to your death."[80] The SS guards would often force prisoners – exhausted from hours of hard labour without sufficient food and water – to race up the stairs carrying blocks of stone. Those who survived the ordeal would often be placed in a line-up at the edge of a cliff known as "The Parachutists' Wall" (German: Fallschirmspringerwand).[83] At gunpoint, each prisoner would have the option of being shot or pushing the prisoner in front of him off the cliff.[39] Other common methods of extermination of prisoners who were either sick, unfit for further labour or as a means of collective responsibility or after escape attempts included beating the prisoners to death by the SS guards and Kapos, starving to death in bunkers, hangings and mass shootings.[84]

At times the guards or Kapos would either deliberately throw the prisoners on the 380-volt electric barbed wire fence,[84] or force them outside the boundaries of the camp and then shoot them on the pretence that they were attempting to escape.[85] Another method of extermination were icy showers – some 3,000 inmates died of hypothermia after having been forced to take an icy cold shower and then left outside in cold weather.[86] A large number of inmates were drowned in barrels of water at Gusen II.[87][88]

The Nazis also performed pseudo-scientific experiments on the prisoners. Among the doctors to organise them were Sigbert Ramsauer, Karl Josef Gross, Eduard Krebsbach and Aribert Heim. Heim was dubbed "Doctor Death" by the inmates; he was in Gusen for seven weeks, which was enough to carry out his experiments.[89][90]

Hans Maršálek Kapo and camp resistance member estimated that an average life expectancy of newly arrived prisoners in Gusen varied from six months between 1940 and 1942, to less than three months in early 1945.[91] Paradoxically, with the growth of forced labour industry in various subcamps of Mauthausen, the situation of some of the prisoners improved significantly. While the food rations were increasingly limited every month, the heavy industry necessitated skilled specialists rather than unqualified workers and the brutality of the camp's SS and Kapos was limited. While the prisoners were still beaten on a daily basis and the Muselmänner were still exterminated, from early 1943 on some of the factory workers were allowed to receive food parcels from their families (mostly Poles and Frenchmen). This allowed many of them not only to evade the risk of starvation, but also to help other prisoners who had no relatives outside the camps – or who were not allowed to receive parcels.[92]

In February 1945, the camp was the site of the Nazi war crime Mühlviertler Hasenjagd ("hare hunt") where around 500 escaped prisoners (mostly Soviet officers) were mercilessly hunted down and murdered by SS, local law enforcement and civilians.[93]

Death toll

[edit]

The Germans destroyed much of the camp's files and evidence and often allocated newly arrived prisoners the camp numbers of those who had already been killed,[53] so the exact death toll of Mauthausen and its subcamps is impossible to calculate. The matter is further complicated due to some of the inmates of Gusen being murdered in Mauthausen, and at least 3,423 were sent to Hartheim Castle, 40.7 km (25.3 mi) away. Overall, more than 90,000 of the 190,000 people deported to Mauthausen died there or in one of its subcamps.[1]

Staff

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2015) |

SS Captain Albert Sauer presided over the initial establishment of the camp on 1 August 1938 and remained camp commandant until 17 February 1939. Franz Ziereis assumed control as commandant of the Mauthausen concentration camp from 1939 until the camp was liberated by the American forces in 1945.[94] The infamous Death's-Head Unit or SS-Totenkopfverbände charged with guarding the camp perimeter in addition to work detachments was headed by Georg Bachmayer, a captain in the SS. Further records of camp leadership were destroyed by Nazi officials in effort to cover up war atrocities and those involved.

Several Norwegian Waffen SS volunteers worked as guards or as instructors for prisoners from Nordic countries, according to senior researcher Terje Emberland at the Center for Studies of Holocaust and Religious Minorities.[95]

Liberation and postwar heritage

[edit]

During the final months before liberation, the camp's commander Franz Ziereis prepared for its defence against a possible Soviet offensive. The remaining prisoners were rushed to build a line of granite anti-tank obstacles to the east of Mauthausen. The inmates unable to cope with the hard labour and malnutrition were exterminated in large numbers to free space for newly arrived evacuation transports from other camps, including most of the subcamps of Mauthausen located in eastern Austria. In the final months of the war, the main source of dietary energy, the parcels of food sent through the International Red Cross, stopped and food rations became catastrophically low. The prisoners transferred to the "Hospital Subcamp" received one piece of bread per 20 inmates and roughly half a litre of weed soup a day.[97] This made some of the prisoners, previously engaged in various types of resistance activity, begin to prepare plans to defend the camp in case of an SS attempt to exterminate all the remaining inmates.[97]

On 3 May the SS and other guards started to prepare for evacuation of the camp. The following day, the guards of Mauthausen were replaced with unarmed Volkssturm soldiers and an improvised unit formed of elderly police officers and firefighters evacuated from Vienna. The police officer in charge of the unit accepted the "inmate self-government" as the camp's highest authority and Martin Gerken, until then the highest-ranking kapo prisoner in the Gusen's administration (in the rank of Lagerälteste, or the Camp's Elder), became the new de facto commander. He attempted to create an International Prisoner Committee that would become a provisional governing body of the camp until it was liberated by one of the approaching armies, but he was openly accused of co-operation with the SS and the plan failed.

All work in the subcamps of Mauthausen stopped and the inmates focused on preparations for their liberation – or defence of the camps against a possible assault by the SS divisions concentrated in the area.[98] The remnants of several German divisions indeed assaulted the Mauthausen subcamp, but were repelled by the prisoners who took over the camp.[25] Of the main subcamps of Mauthausen, only Gusen III was to be evacuated. On 1 May the inmates were rushed on a death march towards Sankt Georgen, but were ordered to return to the camp after several hours. The operation was repeated the following day, but called off soon afterwards. The following day, the SS guards deserted the camp, leaving the prisoners to their fate.[98]

On 5 May 1945 the camp at Mauthausen was approached by a squad of US Army soldiers of the 41st Reconnaissance Squadron of the 11th Armored Division, Third United States Army. The reconnaissance squad was led by Staff Sergeant Albert J. Kosiek.[99][100] His troop disarmed the policemen and left the camp. By the time of its liberation, most of the guards in Mauthausen had fled; around 30 of those who remained were killed by the prisoners. A number of SS men had their heads impaled with stakes, while others were beheaded with their own knives.[101][102] A similar number were killed in Gusen II.[101] By 6 May all the remaining subcamps of Mauthausen, with the exception of the two camps in the Loibl Pass, were also liberated by American forces.[citation needed]

Among the inmates liberated from the camp was Lieutenant Jack Taylor, an officer of the Office of Strategic Services.[103][104] He had managed to survive with the help of several prisoners and was later a key witness at the Mauthausen-Gusen camp trials carried out by the Dachau International Military Tribunal.[105] Another of the camp's survivors was Simon Wiesenthal, an engineer who spent the rest of his life hunting Nazi war criminals. Future Medal of Honor recipient Tibor "Ted" Rubin was imprisoned there as a young teenager; a Hungarian Jew, he vowed to join the US Army upon his liberation and later did just that, distinguishing himself in the Korean War as a corporal in the 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division.[106]

Francesc Boix, a photographer and veteran of the Spanish Civil War, was imprisoned at the camp for four years. During his time working in the photography lab of the camp, he smuggled 3,000 negatives out of the camp and later used this photographic evidence to testify at the Nuremberg trials.[107]

Following the capitulation of Germany, Mauthausen fell within the Soviet sector of occupation of Austria. Initially, the Soviet authorities used parts of the Mauthausen and Gusen I camps as barracks for the Red Army. At the same time, the underground factories were being dismantled and sent to the USSR as a war reparations. After that, between 1946 and 1947, the camps were unguarded and many furnishings and facilities of the camp were dismantled, both by the Red Army and by the local population. In the early summer of 1947, the Soviet forces had blown up the tunnels and were then withdrawn from the area, while the camp was turned over to Austrian civilian authorities.[citation needed]

Memorials

[edit]

Mauthausen was declared a national memorial site in 1949.[108] Bruno Kreisky, the Chancellor of Austria, officially opened the Mauthausen Museum on 3 May 1975, 30 years after the camp's liberation.[4] A visitor centre was inaugurated in 2003, designed by the architects Herwig Mayer, Christoph Schwarz, and Karl Peyrer-Heimstätt, covering an area of 2,845 square metres (30,620 sq ft).[109]

The Mauthausen site remains largely intact, but much of what constituted the subcamps of Gusen I, II, and III is now covered by residential areas built after the war.[110]

A memorial to Mauthausen stands amongst the various memorials to concentration camps in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.[111]

The "Mauthausen Trilogy", also known as "The Ballad of Mauthausen" is a cycle of four arias with lyrics based on poems written by Greek playwright Iakovos Kambanellis, a Mauthausen concentration camp survivor, and music written by Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis.

Documentaries, films and music

[edit]- Mauthausen Trilogy (1965). Cycle of four arias with lyrics based on poems written by Greek poet Iakovos Kambanellis, a Mauthausen concentration camp survivor, and music written by Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis.

- The Quality of Mercy (1994). Austrian film written, directed and produced by Andreas Gruber.

- Joe Zawinul, Mauthausen - Vom großen Sterben hören (2000). Memorial music.[112]

- Mauthausen–Gusen: La memòria] (2008) (in Valencian) by Rosa Brines and Daniel Rodríguez.[113] An 18-minute documentary about the republican Spaniards deported to Mauthausen and Gusen. It includes testimonies from survivors.

- The Photographer of Mauthausen (2018). Based on real events, Francisco Boix is the Spanish photographer and inmate of Mauthausen who saved thousands of pieces of photographic evidence of the horrors committed inside the Austrian concentration camp's walls.[114]

- Resistance at Mauthausen (2021).[115] A 51-minute documentary by Barbara Necek about the resistance by republican Spanish prisoners, focusing particularly on Francisco Boix who preserved thousands of photographs of conditions inside the camp.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Oswald Pohl, apart from being a high-ranking SS member, owner of DEST and several other companies, and chief of administration and treasurer of various Nazi organizations, was also the managing director of the German Red Cross. In 1938, he transferred 8,000,000 Reichsmarks from member fees to one of the accounts of the SS (SS-Spargemeinschaft e. V.), which in turn donated all the money to DEST in 1939.[20]

- ^ As stated in Reinhard Heydrich's memo of 1 January 1941.[26]

- ^ 11,000,000 Reichsmark was equivalent to roughly 4,403,000 US dollars or almost one million sterling by 1939 exchange rates;[41] In turn, 4,403,000 1939 dollars are roughly equivalent to 560,370,000 modern US dollars using the relative share of GDP as the main factor of comparison, or 99.5 million using the consumer price index.[42]

- ^ In reality the actual production never reached such levels.[48]

- ^ The subcamp inmate counts refer to the situation in late 1944 and early 1945, before the major reorganization of the camp's system and before the arrival of a large number of evacuation trains and death marches.

- ^ It is often mentioned that the mortality rate reached 58% in 1941, as compared with 36% at Dachau, and 19% at Buchenwald over the same period. Dobosiewicz – who made the most extensive study – compared various factors: his estimations were based on the number of prisoners to arrive in a year as compared to the number of that were murdered during a year.[20]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Freund & Kranebitter (2016), p. 56.

- ^ a b c "Nowy Sącz, Poland (Pages 213-252)". www.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Dobosiewicz (2000), pp. 191–202.

- ^ a b c Bischof & Pelinka (1996), pp. 185–190.

- ^ a b "Concentration camp Gusen I | Mauthausen Guides - Mauthausen Komitee Österreich". www.mauthausen-guides.at. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Concentration camp Gusen II | Mauthausen Guides - Mauthausen Komitee Österreich". www.mauthausen-guides.at. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ a b c "The History of Mauthausen Concentration Camp | Mauthausen Komitee Österreich". www.mkoe.at. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Holocaust Memorial Day Trust | 5 May 1945: Liberation of Mauthausen Concentration Camp". Holocaust Memorial Day Trust. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Mauthausen/Gusen Death Book". www.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Haunschmied, Mills & Witzany-Durda (2008), pp. 172–175.

- ^ Walden (2000).

- ^ Berenbaum, Michael. "Mauthausen". Encyclopedia Britannica, 29 Jun. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Mauthausen-concentration-camp-Austria. Accessed 21 July 2025

- ^ "Population". mauthausen1.weebly.com. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ "Liberation of Concentration Camps". The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Mauthausen". IHRA. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ "The Liberation of Majdanek". The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. 23 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ "Mauthausen Museum – Mauthausen – Austria". tropter.com. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ "The History of the Mauthausen Concentration Camp Memorial | Mauthausen Komitee Österreich". www.mkoe.at. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 449.

- ^ a b c Haunschmied, Mills & Witzany-Durda (2008), pp. 45–48.

- ^ Pike (2000), p. 89.

- ^ Pike (2000), p. 18.

- ^ Speer (1970), pp. 367–368.

- ^ a b Żeromski (1983), pp. 6–12.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 12.

- ^ a b Maršálek (1995), p. 69.

- ^ Freund & Kranebitter (2016), p. 58.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 13, 47.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 15.

- ^ "The Mauthausen Concentration Camp 1938–1945". Mauthausen Memorial. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 14.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 198.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 25, 196–197.

- ^ a b c Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 193.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 25.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 26.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 240.

- ^ a b Waller (2002), pp. 3–5.

- ^ a b "El sistema de campos de concentración nacionalsocialista, 1933–1945: un modelo europeo" [The national-socialist concentration camp system 1933–1945; European model]. Topografías de la memoria – Memoriales históricos de los campos de concentración nacionalsocialista, 1933-1945 [Topographies of memory – Historical memorials of the National Socialist concentration camps, 1933-1945] (in Spanish).

- ^ Derela (2005).

- ^ Williamson.

- ^ M.S. "Linz – Eisenwerke Oberdonau". Österreichs Geschichte im Dritten Reich (in German). Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ Pike (2000), p. 98.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1980), pp. 37–38.

- ^ Haunschmied & Faeth (1997), p. 1325.

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 194.

- ^ a b c d e Grzesiuk (1985), p. 392.

- ^ a b "Nazi secret weapons site claims refuted". The Local. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Richardson (1995), pp. 162–164.

- ^ Terrance (1999), p. 142.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), p. 343.

- ^ a b c Abzug (1987), pp. 106–110.

- ^ Shermer & Grobman (2002), pp. 168–175.

- ^ Nogaj (1945), p. 64.

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), p. 25.

- ^ Kunert (2009), p. 104.

- ^ a b Preston 2013, p. 516.

- ^ Wnuk (1972), pp. 100–105.

- ^ STA, mm (2012), "Že pred današnjo…".

- ^ Filipkowski (2005).

- ^ Kirchmayer (1978), p. 576.

- ^ a b c Dobosiewicz (2000), pp. 365–367.

- ^ Freund, Florian; Greifeneder, Harald (eds.). "Zeltlager" [Tent Camp]. Mauthausen Memorial (in German). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2006.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 204.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 205.

- ^ KZ Gusen Memorial Committee. "KZ Gusen I Concentration Camp at Langenstein". KZ Mauthausen-GUSEN Info-Pages. The Nizkor Project. Archived from the original on 2 October 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2006.

KZ Gusen Brothel

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 108.

- ^ Berman, Joshua A. (2023). The Book of Lamentations. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. doi:10.1017/9781108334921.004. ISBN 9781108424417. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ Frazer, Jenni (27 February 2025). "Eisenhower's great-grandson meets survivor saved as baby". Jewish News. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- ^ Brown (2002), p. 288.

- ^ a b Friedlander (1981), pp. 33–69.

- ^ Myczkowski (1946), p. 31.

- ^ Bloxham (2003), p. 210.

- ^ a b Burleigh (1997), pp. 210–211.

- ^ Simon Wiesenthal Center. "Mauthausen". Selected Holocaust Glossary: Terms, Places and Personalities. Florida Holocaust Museum. Archived from the original on 8 December 2006. Retrieved 12 April 2006.

- ^ Ziemke, Earl F. (1975). The US Army in the Occupation of Germany, 1944-1946. Washington DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. p. 251. LCCN 75-619027. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007.

- ^ Pike (2000), p. 97.

- ^ Weissman (2004), pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Jones (2015), PT144.

- ^ "Edward Mosberg". USC Shoah Foundation. 16 September 2020.

- ^ a b Krukowski (1966), pp. 292–297.

- ^ "Parachute Jump". Mauthausen Memorial. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ a b Maida, "The systematic and deliberate extermination by hunger, ...".

- ^ Schmidt (2005), pp. 146–148.

- ^ Wnuk (1961), pp. 20–22.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (2000), p. 12.

- ^ Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 102, 276.

- ^ Fuchs (2005).

- ^ Schmidt & Loehrer (2008), p. 146.

- ^ Maršálek (1968), p. 32; as cited in: Dobosiewicz (2000), pp. 192–193.

- ^ Grzesiuk (1985), pp. 252–255.

- ^ Demeritt (1999).

- ^ "Camp SS and Guards". Mauthausen Memorial.

- ^ "Norske vakter jobbet i Hitlers konsentrasjonsleire" [Norwegian guards worked in Hitler's concentration camps]. Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). 15 November 2010. ISSN 0805-5203. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Pike (2000), p. 256.

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 374–375.

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 382–388.

- ^ Pike (2000), pp. 233–234.

- ^ Radd (2020).

- ^ a b Dobosiewicz (1977), pp. 395–397.

- ^ "Article clipped from Chicago Tribune". Chicago Tribune. 8 June 1945. p. 6. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ "Jack Taylor, American Agent Who Survived Mauthausen". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ Pike (2000), p. 237.

- ^ Taylor (2003).

- ^ "Medal of Honor Recipients – Korean War: TIBOR RUBIN". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Lloyd, Nick (30 November 2010). "Capturing Evil - Francesc Boix". Barcelona Metropolitan. Archived from the original on 24 May 2025. Retrieved 6 November 2025.

- ^ "History of the Mauthausen Memorial". Mauthausen Memorial.

- ^ van Uffelen (2010), pp. 150–153.

- ^ Terrance (1999), pp. 138–139.

- ^ "Paris walks: Père-Lachaise". Time Out. 21 November 2016.

- ^ "Uraufführung der Orchesterfassung von Joe Zawinuls "Mauthausen … vom großen Sterben hören" im MuTh". MUK (in German). 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Mauthausen–Gusen: La memòria". Jaume I University.

- ^ Antón (2017).

- ^ "Resistance at Mauthausen". CLPB Rights.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abzug, Robert (1987). Inside the Vicious Heart. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 106–110. ISBN 0-19-504236-0.

- Antón, Jacinto (23 November 2017). "La vida del fotógrafo que sufrió el horror nazi se convierte en película". El País. Prisa. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- Bischof, Günter; Pelinka, Anton (1996). Austrian Historical Memory and National Identity. Transaction Publishers. pp. 185–190. ISBN 1-56000-902-0.

- Bloxham, Donald (2003). Genocide on Trial: War Crimes Trials and the Formation of Holocaust History and Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 210. ISBN 0-19-925904-6.

- Brown, Daniel Patrick (2002). The Camp Women: The Female Auxiliaries Who Assisted the SS in Running the Nazi Concentration Camp System. Schiffer Publishing. p. 288. ISBN 0-7643-1444-0.

- Burleigh, Michael (1997). Ethics and Extermination: Reflections on Nazi Genocide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 210–211. ISBN 0-521-58816-2.

- Demeritt, Linda C. (1999). "Representations of History: The "Mühlviertler Hasenjagd" as Word and Image". Modern Austrian Literature. 32 (4): 135–145. JSTOR 24648890.

- Derela, Michał Derela (16 March 2005). "The prices of Polish armament before 1939". The PIBWL military site. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2006.

- Dobosiewicz, Stanisław (1977). Mauthausen/Gusen; obóz zagłady [Mauthausen/Gusen; the Camp of Doom] (in Polish). Warsaw: Ministry of National Defence Press. p. 449. ISBN 83-11-06368-0.

- Dobosiewicz, Stanisław (1980). Mauthausen/Gusen; Samoobrona i konspiracja [Mauthausen/Gusen: self-defence and underground] (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwa MON. p. 486. ISBN 83-11-06497-0.

- Dobosiewicz, Stanisław (2000). Mauthausen–Gusen; w obronie życia i ludzkiej godności [Mauthausen–Gusen; in defence of life and human dignity] (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. pp. 191–202. ISBN 83-11-09048-3.

- Filipkowski, Piotr (13 October 2005). "Auschwitz w drodze do Mauthausen" [Auschwitz, en route to Mauthausen]. Europe According to Auschwitz (in Polish). Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- Freund, Florian; Kranebitter, Andreas (2016). "On the Quantitative Dimension of Mass Murder at the Mauthausen Concentration Camp and its Subcamps". Memorial Book for the Dead of the Mauthausen Concentration Camp: Commentaries and Biographies. Vienna: New Academic Press. pp. 56–67. ISBN 978-3-7003-1975-7.

- Friedlander, Henry. "The Nazi Concentration Camps". In Ryan (1981), pp. 33–69.

- Fuchs, Dale (17 October 2005). "Nazi war criminal escapes Costa Brava police search". Guardian. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- Grzesiuk, Stanisław (1985). Pięć lat kacetu [Five Years of KZ] (in Polish). Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. pp. 252–255, 392. ISBN 83-05-11108-3.

- Haunschmied, Rudolf; Faeth, Harald (1997). "B8 "BERGKRISTALL" (KL Gusen II)". Tunnel and Shelter Researching. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- Haunschmied, Rudolf A.; Mills, Jan-Ruth; Witzany-Durda, Siegi (2008). St. Georgen-Gusen-Mauthausen – Concentration Camp Mauthausen Reconsidered. Norderstedt: Books on Demand. p. 289. ISBN 978-3-8334-7610-5. OCLC 300552112.

- Jones, Michael (2015). After Hitler: The Last Ten Days of World War II in Europe. Penguin. ISBN 9780698407817.

- Kirchmayer, Jerzy (1978). Powstanie warszawskie [Warsaw Uprising] (in Polish). Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. p. 576. ISBN 83-05-11080-X.

- Krukowski, Stefan (1966). "Pamięci lekarzy" [In memoriam of the doctors]. Nad pięknym modrym Dunajem; Mauthausen 1940–1945 [Mauthausen 1940–1945: At The Blue Danube] (in Polish). Tadeusz Żeromski (foreword). Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. pp. 292–297. PB 9330/66.

- Kunert, Andrzej (2009). Człowiek człowiekowi… Niszczenie polskiej inteligencji w latach 1939–1945 KL Mauthausen/Gusen [Man to Man…; The destruction of Polish intelligentsia 1939–1945 in the camps of Mauthausen/Gusen] (in Polish). Various authors. Warsaw: Rada Ochrony Pamięci Walk i Męczeństwa. p. 104.

- Maida, Bruno. "The gas chamber of Mauthausen – History and testimonies of the Italian deportees; A Brief history of the camp". Biblioteca archivio Pina e Aldo Ravelli. ANED - Associazione nazionale ex deportati politici nei campi nazisti. Archived from the original on 5 June 2006.

- Maršálek, Hans (1968). Konzentrazionslager Gusen: kurze dokumentarische Geschichte eines Nebenlagers des KZ Mauthausen [Gusen concentration camp: short documentary history of a subcamp of the Mauthausen concentration camp] (in German). Wien: Österreichische Lagergemeinschaft Mauthausen. p. 32. OCLC 947175024.

- Maršálek, Hans (1995). Die Geschichte des Konzentrationslagers Mauthausen [History of Mauthausen Concentration Camp] (in German). Wien-Linz: Österreichischen Lagergemeinschaft Mauthausen u. Mauthausen-Aktiv Oberösterreich.

- Myczkowski, Adam (1946). Poprzez Dachau do Mauthausen–Gusen [Through Dachau to Mauthausen–Gusen] (in Polish). Kraków: Księgarnia Stefana Kamińskiego. p. 31.

- Nogaj, Stanisław (1945). Gusen; Pamiętnik dziennikarza [Gusen; Memoir of a Journalist] (in Polish). Katowice-Chorzów: Komitet byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego Gusen. p. 64.

- Osuchowski, Jerzy, ed. (1961). Oskarżamy! Materiały do historii obozu koncentracyjnego Mauthausen–Gusen [We Accuse! Materials on the History of Mauthausen–Gusen Concentration Camp] (in Polish). Katowice: Klub Mauthausen–Gusen ZBoWiD.

- Pike, David Wingeate (2000). Spaniards in the Holocaust: Mauthausen, Horror on the Danube. London: Routledge. p. 480. ISBN 0-415-22780-1.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1998). Poland's holocaust: ethnic strife, collaboration with occupying forces and genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. McFarland.

- Preston, Paul (2013). The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393345912.

- Radd, Maggie (6 May 2020). "75th Anniversary Of The Liberation Of Mauthausen". Museum of Jewish Heritage. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- Richardson, Elizabeth C. (1995). "United States vs. Leprich". Administrative Law and Procedure. Thomson Delmar Learning. pp. 162–164. ISBN 0-8273-7468-2.

- Ryan, Michael D., ed. (1981). Human Responses to the Holocaust Perpetrators and Victims, Bystanders and Resisters. various authors. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946-901-6.

- Schmidt, Amy; Loehrer, Gudrun, eds. (2008). "The Mauthausen Concentration Camp Complex: World War II and Postwar Records" (PDF). Reference Information Paper. 115. various authors. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration: 145–148. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- Schmidt, James (2005). ""Not These Sounds": Beethoven at Mauthausen" (PDF). Philosophy and Literature. 29. Boston: Boston University: 146–163. doi:10.1353/phl.2005.0013. ISSN 0190-0013. S2CID 201741314. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Shermer, Michael; Grobman, Alex (2002). "The Gas Chamber at Mauthausen". Denying History: Who Says the Holocaust Never Happened and Why Do They Say It?. University of California Press. pp. 168–175. ISBN 0-520-23469-3.

- Speer, Albert (1970). Inside The Third Reich. New York: The Macmillan Company. ISBN 0-88365-924-7.

- STA, mm (13 May 2012). "Taborišče, v katerem je umrlo 1500 Slovencev" [Camp, in which 1500 Slovenes died]. Mladina (in Slovenian). ISSN 1580-5352. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- Taylor, Jack (2003). "OSS Archives: The Dupont Mission". The Blast. UDT-SEAL Association. Archived from the original on 27 January 2006. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- Terrance, Marc (1999). Concentration Camps: A Traveler's Guide to World War II Sites. Universal Publishers. ISBN 1-58112-839-8.

- van Uffelen, Chris (2010). Contemporary Museums – Architecture, History, Collections. Braun Publishing. pp. 150–153. ISBN 9783037680674.

- Walden, Geoffrey R. (20 July 2000). "Gusen Concentration Camp / Project B-8 "Bergkristall" Tunnel System". The Third Reich in Ruins. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Waller, James (2002). Becoming Evil: How Ordinary People Commit Genocide and Mass Killing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 0-19-514868-1.

- Weissman, Gary (2004). Fantasies of Witnessing: Postwar Efforts to Experience the Holocaust. Cornell University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-8014-4253-2.

- Williamson, Samuel H. "Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to present". MeasuringWorth.

- Wnuk, Włodzimierz. "Śmiertelne kąpiele [Deadly Baths]". In Osuchowski (1961), pp. 20–22.

- Wnuk, Włodzimierz (1972). "Z Hiszpanami w jednym szeregu" [With the Spaniards in One Line]. Byłem z wami [I Was With You] (in Polish). Warsaw: PAX. pp. 100–105.

- Żeromski, Tadeusz (1983). Rusinek, Kazimierz (ed.). Międzynarodówka straceńców [Desperados' Internationale] (in Polish). Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. ISBN 83-05-11175-X.

Further reading

[edit]- Cyra, Adam (16 July 2004). "Mauthausen Concentration Camp Records in the Auschwitz Museum Archives". Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. Historical Research Section, Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum. Archived from the original on 30 September 2006. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- Evelyn Le Chêne (1971). Mauthausen, The History of a Death Camp. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-07780-3.

- Filip, Marian; Łomacki, Mikołaj, eds. (1962). Wrogom ku przestrodze: Mauthausen 5 maja 1945 [Enemies Beware; Mauthausen, 5 May 1945] (in Polish). various authors. Warsaw: ZG ZBoWiD.

- Fisher, Joseph (2017). The Heavens were Walled In. Vienna: New Academic Press. ISBN 978-3-7003-1956-6.

- Gębik, Władysław (1972). Z diabłami na ty [Calling the Devils by their Names] (in Polish). Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Morskie.

- Gilbert, Martin (1987). The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War. Owl Books. p. 976. ISBN 0-8050-0348-7.

- Hlaváček, Stanislav (2000). "Historie KTM" [History of the Mauthausen Concentration Camp]. Koncentrační Tábor Mauthausen; Pamětní tisk k 55. výročí osvobození KTM [Mauthausen concentration camp: Memorial publication for the 55th anniversary of the liberation] (in Czech). Retrieved 18 May 2006.

- Snyder, Timothy D. (2015). Black Earth. The Holocaust As History and Warning. Crown. ISBN 978-1-101-90346-9.

- Wlazłowski, Zbigniew (1974). Przez kamieniołomy i kolczasty drut [Through the Quarries and Barbed Wire] (in Polish). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. PB 1974/7600.

- Austrian Ministry of the Interior (2005). Das sichtbare Unfassbare – Fotografien aus dem Konzentrationslager Mauthausen [The Visible Part – Photographs of Mauthausen Concentration Camp]. Vienna: Mandelbaum Verlag. ISBN 978385476-158-7.

- "Pracownicy muzeum Auschwitz zeskanowali już kartotekę Mauthausen" [The Workers of Auschwitz Museum Have Scanned the Mauthausen Files]. wiadomosci.wp.pl (in Polish). Polish Press Agency. 3 April 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

External links

[edit]- USHMM United States Holocaust Memorial Museum contains more than 500 pictures of Mauthausen–Gusen

- Interviews with American servicemen imprisoned at Mauthausen

- Online exhibition of the Polish History Museum on the former KZ Gusen complex

- Mauthausen Memorial

Mauthausen concentration camp

View on GrokipediaMauthausen concentration camp was a Nazi German complex established on August 8, 1938, shortly after the Anschluss of Austria, located on a hill overlooking the town of Mauthausen in Upper Austria adjacent to the Wiener Graben granite quarry.[1][2] The camp served primarily as a site for forced labor, initially in quarrying stone but expanding to armaments production in subcamps, under SS administration that enforced extermination through work, resulting in at least 95,000 deaths out of approximately 197,000 prisoners who passed through the system by May 1945.[1][2] Classified as a Category III camp for the most severe "incorrigible" political prisoners, Mauthausen featured brutal conditions exemplified by the "Stairs of Death"—186 steep steps where inmates hauled heavy granite blocks, often leading to fatal falls or beatings by guards.[3][1] Prisoners included Austrians, Germans, Poles, Soviet civilians and POWs, Spanish Republicans, Jews, and others labeled as state enemies, with women comprising a small but growing number by 1945.[1] The main camp and nearly 50 subcamps, such as Gusen and Ebensee, supported the German war economy through slave labor in underground factories and other industries.[1][2] Executions via gas chamber, injections, and hurling from quarry cliffs supplemented deaths from starvation, disease, and overwork.[3] Under commandant Franz Ziereis from 1939, the SS guards perpetrated systematic violence, earning Mauthausen a reputation as one of the deadliest camps, with operations ceasing only upon liberation by the U.S. 11th Armored Division on May 5, 1945, after prisoners had seized control from fleeing SS personnel.[3][1] Post-liberation, thousands of survivors required immediate medical aid amid ongoing fatalities from prior abuses.[3]

Establishment and Infrastructure

Founding and Initial Setup

The Mauthausen concentration camp was founded in the wake of Austria's Anschluss with Nazi Germany on March 12, 1938. Gauleiter of Upper Austria August Eigruber announced the establishment of a concentration camp at Mauthausen on March 26, 1938, targeting political opponents, criminals, and asocial elements for detention.[2] The site's selection was driven by its location near the state-owned Wiener Graben granite quarry, intended for exploitation through forced labor by the SS-controlled German Earth and Stone Works company (DESt), which had leased the quarry prior to the camp's opening.[1][4] On August 8, 1938, the first group of approximately 300 male prisoners—primarily Austrians and Germans categorized as repeat offenders, asocials, or political detainees—arrived from Dachau concentration camp to initiate construction of the camp infrastructure.[1][2] Accompanying SS guards, also transferred from Dachau, supervised the work, which included erecting barracks on a hill above the town of Mauthausen and developing access to the quarry.[5] SS Captain Albert Sauer served as the initial commandant from August 1, 1938, until February 17, 1939.[1] By late 1938, the prisoner population expanded to nearly 1,000, with inmates housed initially in provisional structures while permanent facilities were completed using their own labor.[1] The camp's design emphasized isolation and control, positioned overlooking the Danube River valley approximately 3 miles from Mauthausen town and 12.5 miles southeast of Linz.[1] This setup facilitated immediate integration with quarry operations, where prisoners faced grueling conditions from the outset.[4]Quarry Integration and Camp Design

The Mauthausen concentration camp was established in Upper Austria on a hillside overlooking the town of Mauthausen and the Danube River, strategically sited adjacent to the pre-existing Wiener Graben granite quarry to facilitate SS exploitation of its resources. Following Austria's Anschluss to Nazi Germany on March 12, 1938, the SS selected this location to integrate forced prisoner labor with the production of building materials through the newly founded Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH (DESt) enterprise, established in April 1938, which aimed to supply granite for monumental Nazi construction projects such as the expansion of Linz. The quarry's proximity—directly below the camp—ensured that labor extraction was central to the camp's operational design from inception.[1][4] Initial construction of the camp began in August 1938 with approximately 300 prisoners transferred from Dachau concentration camp, who were compelled to quarry granite on-site and use it to erect the camp's barracks, walls, and infrastructure. This self-sustaining design leveraged the quarry not only for external production but also for internal camp building, minimizing external material costs and maximizing prisoner exhaustion as a tool of control and punishment. By December 1938, the camp held nearly 1,000 prisoners, primarily categorized as criminals and asocials, whose labor solidified the quarry-camp linkage. The integration reflected the SS's broader strategy from the late 1930s to align concentration camps with industrial ambitions in quarrying and stoneworking.[1][2] The camp's layout was engineered for isolation and surveillance, perched elevated above the quarry to enable direct oversight of labor below, with the infamous 186-step "Stairs of Death" (Todesstiege) serving as the primary vertical conduit between the quarry floor and camp plateau. Prisoners were routinely forced to haul blocks weighing up to 50 kilograms up these uneven, steeply inclined stairs, a feature that embodied the camp's designation as a severe "Category III" site intended for the harshest conditions and extermination through work. This architectural choice amplified mortality rates, as falls, exhaustion, or deliberate pushes off the stairs became common, particularly for penal detachments and targeted groups like Dutch Jews between 1941 and 1942. By 1942, over 3,300 prisoners were deployed in quarry operations across Mauthausen and its early subcamps, underscoring the quarry's embedded role in the camp's punitive design.[2][4][1]Expansion and Network

Gusen Subcamp Development

The SS initiated development of the Gusen subcamp to access high-quality granite deposits in the Gusen quarries, which exceeded the capacity of the Mauthausen quarry for forced labor exploitation by the SS-owned Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke (DESt) company.[6] Construction commenced in December 1939, with daily work parties of prisoners marched from Mauthausen to the site before formal camp establishment; the initial infrastructure, including barracks, was erected by German, Austrian, and Polish prisoners during the harsh winter of 1939–1940.[7] [6] Gusen I opened on May 25, 1940, with the arrival of the first transport comprising 1,084 Polish prisoners, and was designed to accommodate approximately 6,000 inmates, surpassing the size of the Mauthausen main camp.[7] Primarily focused on granite quarrying under lethal conditions that yielded mortality rates several times higher than at Mauthausen—particularly in 1941—the camp registered over 60,000 prisoners throughout its operation, with an estimated 35,000 to 36,000 deaths from exhaustion, starvation, disease, and executions.[6] [7] As wartime armaments demands intensified from 1943, labor shifted from quarrying to weapons production for firms such as Steyr-Daimler-Puch (rifles) and Messerschmitt (aircraft components), prompting further expansion to protect facilities from Allied bombing. Gusen II was established on March 9, 1944, along the St. Georgen road, housing up to 10,000 prisoners for munitions work and tunnel excavation in the Bergkristall (B8) project, where approximately 6,000 inmates at a time labored on underground assembly of Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighters; at least 8,600 perished there due to conditions.[7] [6] Gusen III followed in December 1944 at Lungitz, a smaller facility with 260 prisoners assigned to brick production and depot duties.[7] The overall Gusen complex peaked at 26,311 prisoners in February 1945, reflecting the SS's prioritization of output over survival amid escalating war production needs.[7]Broader Subcamp System

The broader subcamp system of Mauthausen expanded significantly from 1941/42, as the SS transferred increasing numbers of prisoners to satellite sites across Austria for forced labor, supplementing the main camp and Gusen complex.[8] This network grew to over 40 subcamps by the camp's liberation in May 1945, with approximately 64,000 prisoners—out of a total system population of 83,000—housed in these facilities as of early March 1945.[8] Initially, subcamps supported infrastructure development, including the construction of transport routes, power stations, and factories essential to the Nazi war effort.[8] From late 1943, amid intensifying Allied air raids, the focus shifted to underground armaments production, with prisoners excavating massive tunnel networks to relocate factories and safeguard production from bombardment.[8] These sites exploited prisoner labor for companies involved in munitions and aircraft manufacturing, contributing to Germany's desperate armaments push in the war's final years. Key subcamps included Ebensee, established in 1943 near the Traun River, where over 16,000 prisoners at peak worked on tunneling for a top-secret rocket and bomb production facility under steep cliffs, resulting in thousands of deaths from collapse, disease, and overwork.[8] Melk, opened in 1944 in a former monastery, deployed around 7,000 prisoners to build underground halls for aircraft engine assembly, enduring similar lethal conditions in damp, unventilated tunnels.[8] Other notable sites, such as Loiblpass and Redl-Zipf, focused on tunnel construction for armaments relocation, with prisoner mortality rates often exceeding 50% due to exhaustion, inadequate rations, and SS brutality.[9] The subcamp system's decentralized structure allowed the SS to maximize labor output while dispersing risks, but it perpetuated the main camp's regime of terror, with guards enforcing quotas through beatings, executions, and denial of medical care.[1] At least 90,000 prisoners died across the entire Mauthausen complex, including subcamps, from 1938 to 1945, underscoring the network's role in systematic extermination through labor.[10]Labor Exploitation

Quarry Operations and Stone Production

The Wiener Graben quarry, adjacent to the Mauthausen main camp, served as the primary site for stone extraction under SS control. Following the annexation of Austria in March 1938, the SS established Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH (DEST) to exploit natural resources using concentration camp labor, with Mauthausen camp founded on August 8, 1938, specifically to supply workers for the quarry.[9] Prisoners, primarily political opponents, criminals, and later Soviet POWs and Jews, were forced into grueling extraction tasks, including blasting, cutting, and transporting granite blocks under the oversight of SS personnel and kapos.[9] The quarry's high-quality granite was processed for use in Nazi infrastructure projects, such as roads, buildings, and fortifications, aligning with DEST's goal of economic self-sufficiency for the SS.[9] Central to operations was the "Stairway of Death," a flight of 186 uneven steps hewn into the quarry cliff, requiring prisoners to haul stones weighing 40 to 60 kilograms or more from the pit below the camp to processing areas above.[11] Daily routines involved 10-12 hour shifts in hazardous conditions, with quotas demanding relentless output; failure to meet them or accidental drops often resulted in immediate execution by guards pushing victims off the cliffs or beating them to death.[9] In one documented incident during winter 1939, 170 prisoners perished in a single workday at Wiener Graben due to exhaustion and abuse.[9] Stone production emphasized rough-hewn blocks for DEST's construction enterprises, though precise annual output figures remain undocumented in surviving records; the quarries at Mauthausen and subcamps like Gusen supplemented SS finances through sales to state and private entities.[9] Oversight by figures such as quarry master Otto Drabek and manager Johannes Grimm ensured maximal exploitation, with labor conditions calibrated to induce high mortality rates, classifying Mauthausen as a "Grade III" camp reserved for extermination through toil.[9] By 1942, as war demands shifted, quarry work persisted alongside expanding armaments production, but Wiener Graben's role in granite supply endured until the camp's liberation in May 1945.[9]Armaments Production and Corporate Involvement

Following a labor shortage induced by World War II, the SS redirected Mauthausen prisoners from primarily punitive quarry work toward armaments production starting in April 1942, under SS economic chief Oswald Pohl's directive to integrate camp labor into the German war economy.[12] By spring 1943, Reich Minister of Armaments Albert Speer advocated for fuller utilization after inspecting Mauthausen, leading to thousands of prisoners deployed in protected underground facilities by late 1943.[12] This shift prioritized output over prisoner survival, resulting in extreme mortality rates amid construction and manufacturing demands.[12] Steyr-Daimler-Puch AG was the first Austrian firm to employ Mauthausen prisoners for armaments in March 1942, establishing subcamps including Steyr-Münichholz and leveraging Gusen labor for producing components such as Karabiner 98 rifle parts and MP 44/45 assault rifle parts.[12] [13] Operations began in spring 1942, selecting skilled and robust prisoners, though conditions remained lethal with risks of execution for suspected sabotage like deliberate part malformation.[13] The company expanded prisoner use across sites like Gusen, Melk, and St. Valentin for aircraft-related work, marking early private-sector integration of concentration camp labor.[12] Messerschmitt GmbH collaborated extensively from 1943, utilizing Gusen and Mauthausen prisoners for fighter aircraft assembly, culminating in the Bergkristall underground complex at St. Georgen an der Gusen (code ESCHE 2).[12] Construction commenced on 9 March 1944, with production of Me 262 jet fighter fuselages starting in summer 1944 across over 50,000 m² of tunnels; approximately 10,000 prisoners worked in manufacturing and 6,500 in excavation, drawn mainly from Gusen II and transfers from Auschwitz.[14] The facility yielded 987 fuselages, peaking at 450 per month in April 1945, but at staggering human cost: mortality approached 98% with average survival of four months and estimates of 8,000 to 20,000 deaths.[14] Other firms like Reichswerke Hermann Göring incorporated prisoners from early 1943 for iron and steel processing in Linz, while Heinkel AG employed them near Vienna for fighter plane components, reflecting broader industrial reliance on the Mauthausen network's forced labor.[12] The SS-owned Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke (DEST) also facilitated armaments projects alongside its quarry operations, channeling prisoner output to sustain Nazi war efforts until liberation in May 1945.[12]Specialized Projects and Research

One of the most specialized labor projects in the Mauthausen camp system was the construction of the Bergkristall underground factory complex near St. Georgen an der Gusen, initiated in 1943 to relocate vulnerable armaments production away from Allied bombing raids.[15] This project involved excavating extensive tunnel networks totaling over 8.5 kilometers in length and covering approximately 50,000 square meters, designed primarily for the assembly of Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighter aircraft components under the code name "Bergkristall."[14] Prisoners from Mauthausen and its Gusen subcamps, including large numbers of Jewish inmates, were compelled to perform the grueling tunnel-digging and reinforcement work in continuous three-shift rotations around the clock.[15] The Bergkristall effort exemplified the SS's strategy of exploiting concentration camp labor for high-priority, secretive wartime infrastructure, with production reaching operational status by late 1944 despite severe disruptions.[14] Thousands of prisoners were deployed monthly to sustain the workforce, as exhaustion, starvation, accidents, and executions led to dozens of deaths daily and necessitated constant replenishment via new transports.[15] This resulted in exceptionally high mortality rates among the forced laborers, contributing significantly to the overall death toll in the Gusen subcamps, where conditions were deliberately lethal to enforce "extermination through work."[15] Limited evidence exists of formal scientific research projects at Mauthausen beyond routine medical abuses, though prisoner labor supported ancillary technical developments tied to armaments dispersal, such as engineering assessments for tunnel stability and ventilation systems essential to Bergkristall's functionality.[2] These efforts were overseen by SS engineers in collaboration with firms like Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm, prioritizing output over prisoner welfare and yielding partial success in underground production before the camps' liberation in May 1945.[14]Prisoner Demographics

National and Ethnic Composition

The Mauthausen concentration camp system held approximately 197,000 prisoners from over 40 nationalities between August 1938 and May 1945.[1] These included political opponents, criminals, Soviet prisoners of war, Jews, Roma, and forced laborers from occupied territories.[16] Non-Jewish Poles constituted the largest single national group, with over 37,000 registered.[1] Soviet prisoners formed another major contingent, comprising nearly 23,000 civilians and over 10,000 prisoners of war, many of whom endured high mortality due to targeted mistreatment as ideological enemies.[1] Spanish Republicans, deported primarily from French internment camps between 1940 and 1941, numbered over 7,000, representing a significant early influx of antifascist exiles.[1] Yugoslav civilians accounted for 6,200 to 8,650 prisoners, while Italians totaled around 6,300 following Italy's capitulation in September 1943.[1] Czech prisoners exceeded 4,000, often including intellectuals and resistance figures.[1] Jews, as an ethnic and religious group, numbered between 14,000 and 29,500, including many unregistered arrivals subjected to immediate extermination processes; their survival rates were the lowest among all categories.[1] Roma prisoners, another persecuted ethnic minority, were present in smaller numbers, marked for elimination under Nazi racial policies.[16] Smaller groups included Allied military personnel, such as 47 downed airmen (39 Dutch, 7 British, 1 American) executed in 1944, and members of the International Brigades from various nations who fought in the Spanish Civil War.[1] The camp's diverse composition reflected Nazi expansion, with Slavic and Soviet groups facing particularly harsh conditions due to racial hierarchies, while national origins were indicated on prisoner uniforms alongside category markings.[16]Prisoner Categories and Markings

Prisoners at Mauthausen concentration camp were classified by the SS according to the alleged reasons for their imprisonment, with categories indicated by colored inverted triangles sewn onto the left breast and right trouser leg of their striped uniforms, often accompanied by letters denoting subcategories or nationality.[16] [17] This system, standardized across Nazi camps from 1937–1938, facilitated identification and stigmatization, with green triangles for professional criminals, red for political opponents under "protective custody," black for asocials, pink for those convicted under Paragraph 175 (homosexuality), purple for Jehovah's Witnesses labeled "Bible students," and brown for Roma and Sinti classified as "Gypsies."[17] [16] Non-German prisoners received an additional letter for their country of origin starting in 1939, such as "P" for Poles or "S" for Soviets, which further influenced treatment and survival rates.[16] [17] Political prisoners, marked with red triangles, constituted the dominant category at Mauthausen from its opening in August 1938, primarily comprising German and Austrian opponents of the regime, including communists, social democrats, and trade unionists held under protective custody orders.[16] By 1941, this expanded to include Spanish Republicans—many anarchists and communists deported after the Spanish Civil War—who wore a distinctive blue inverted triangle superimposed on red to denote foreign political prisoners. Soviet prisoners of war and civilians, arriving from October 1941, were often classified as political or asocial, bearing red or black triangles with "SU" lettering, and subjected to especially brutal conditions reflecting Nazi racial ideology.[16] Jews, identified by yellow triangles or a Star of David formed by two overlapping yellow triangles (sometimes overlaid on another color for dual classification, such as red-and-yellow for political Jews), were interned in increasing numbers after 1939 but systematically deprioritized in the camp hierarchy, with the lowest survival rates alongside "preventive detention" prisoners from the penal system.[16] [17] Criminals with green triangles frequently secured privileged functionary roles within the prisoner self-administration, exploiting the system to dominate others, while smaller groups like emigrants, Wehrmacht deserters, and civilian foreign workers received tailored markings such as additional letters or sub-triangles.[16] Unlike Auschwitz, Mauthausen did not tattoo numbers on prisoners; instead, metal or cloth badges with sequential numbers were attached near the triangles for identification.[18]| Category | Triangle Color | Key Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Political (protective custody) | Red | Communists, resistance fighters; largest group, included Spanish Republicans (blue over red) and Soviets ("SU").[16] |

| Professional criminals | Green | Often held privileged positions in prisoner hierarchy.[16] |

| Asocials | Black | Nonconformists, vagrants; included some Soviet civilians.[17] [16] |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | Purple | Labeled "Bible students"; refused military service.[16] [17] |

| Homosexuals (§175) | Pink | Men accused of same-sex relations.[16] [17] |

| Roma/Sinti ("Gypsies") | Brown | Racial classification; variable application across camps.[16] [17] |

| Jews | Yellow (or Star of David) | Often combined with other colors; lowest survival post-1939.[16] [17] |

| Preventive detention/penal | Variable | From regular prisons; high mortality from 1942.[16] |