Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

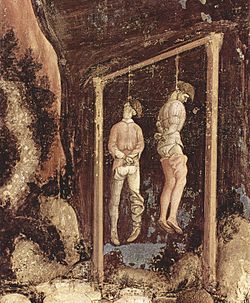

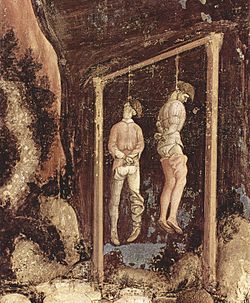

Hanging

View on Wikipedia

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerous countries and regions. As a form of execution, it is commonly practiced at a structure called a gallows. The first known account of execution by hanging is in Homer's Odyssey.[1] Hanging is also a common method of suicide.

Methods of judicial hanging

[edit]There are numerous methods of hanging in execution that instigate death either by cervical fracture or by strangulation.

Short drop

[edit]The short drop is a method of hanging in which the condemned prisoner stands on a raised support, such as a stool, ladder, cart, horse, or other vehicle, with the noose around the neck. The support is then moved away, leaving the person dangling from the rope.[2][3] Suspended by the neck, the weight of the body tightens the noose around the neck, effecting strangulation and death. Loss of consciousness is typically rapid and death ensues in a few minutes.[4]

Before 1850, the short drop was the standard method of hanging, and it is still common in suicides and extrajudicial hangings (such as lynchings and summary executions) which lack the specialised equipment and drop-length calculation tables used in the newer methods.

Pole method

[edit]

A short-drop variant is the Austro-Hungarian "pole" method, called Würgegalgen (literally: strangling gallows), in which the following steps take place:

- The condemned is made to stand before a specialized vertical pole or pillar, approximately 3 metres (9.8 ft) in height.

- A rope is attached around the condemned's feet and routed through a pulley at the base of the pole.

- The condemned is hoisted to the top of the pole by means of a sling running across the chest and under the arms.

- A narrow-diameter noose is looped around the prisoner's neck, then secured to a hook mounted at the top of the pole.

- The chest sling is released, and the prisoner is rapidly jerked downward by the assistant executioners via the foot rope, thus resulting in strangulation and death.

This method was later also adopted by the successor states, most notably by Czechoslovakia, where the "pole" method was used as the single type of execution from 1918 until 1954, when the prison hosting Czechoslovakia's executions, Pankrác Prison, constructed an indoor gallows that exclusively accommodated short-drop hangings to replace the pole method.[5] Nazi war criminal Karl Hermann Frank, executed in 1946 in Prague, was among approximately 1,000 condemned people executed by the pole hanging method in Czechoslovakia.[6]

Standard drop

[edit]

The standard drop involves a drop of between 4 and 6 feet (1.2–1.8 m) and came into use from 1866, when the scientific details were published by Irish doctor Samuel Haughton. Its use rapidly spread to English-speaking countries and those with judicial systems of English origin.

It was considered a humane improvement on the short drop because it was intended to be enough to break the person's neck, causing immediate unconsciousness and rapid brain death.[7][8]

This method was used to execute condemned Nazis under United States jurisdiction after the Nuremberg Trials, including Joachim von Ribbentrop and Ernst Kaltenbrunner.[9][not specific enough to verify] In the execution of Ribbentrop, historian Giles MacDonogh records that: "The hangman botched the execution and the rope throttled the former foreign minister for 20 minutes before he expired."[10] A Life magazine report on the execution merely says: "The trap fell open and with a sound midway between a rumble and a crash, Ribbentrop disappeared. The rope quivered for a time, then stood tautly straight."[11]

Long drop

[edit]

The long-drop process, also known as the measured drop, was introduced to Britain in 1872 by William Marwood as a scientific advance on the standard drop, and further refined by his successor James Berry. Instead of everyone falling the same standard distance, the person's height and weight[12] were used to determine how much slack would be provided in the rope so that the distance dropped would be enough to ensure that the neck was broken, but not so much that the person was decapitated. Careful placement of the eye or knot of the noose (so that the head was jerked back as the rope tightened) contributed to breaking the neck.

Prior to 1892, the drop was in the range of 4–10 ft (1.2–3.0 m), depending on the weight of the body, and was calculated to deliver an energy of 1,260 foot-pounds force (1,710 J), which fractured the neck at either the 2nd and 3rd or 4th and 5th cervical vertebrae. This force resulted in some decapitations, such as the infamous case of Black Jack Ketchum in New Mexico Territory in 1901, owing to a significant weight gain while in custody not having been factored into the drop calculations. Between 1892 and 1913, the length of the drop was shortened to avoid decapitation. After 1913, other factors were also taken into account, and the energy delivered was reduced to about 1,000 foot-pounds force (1,400 J). The record speed for a British long-drop hanging was seven seconds from the executioner entering the cell to the drop. Speed was considered to be important in the British system as it reduced the condemned's mental distress.[13]

Long-drop hanging is still practiced as the method of execution in a few countries, including Japan and Singapore.[14][15]

As suicide

[edit]

Hanging is a common suicide method. The materials necessary for suicide by hanging are readily available to the average person, compared with firearms or poisons. Full suspension is not required, and for this reason, hanging is especially commonplace among suicidal prisoners . A type of hanging comparable to full suspension hanging may be obtained by self-strangulation using a ligature around the neck and the partial weight of the body (partial suspension) to tighten the ligature. When a suicidal hanging involves partial suspension the deceased is found to have both feet touching the ground, e.g., they are kneeling, crouching or standing. Partial suspension or partial weight-bearing on the ligature is sometimes used, particularly in prisons, mental hospitals or other institutions, where full suspension support is difficult to devise, because high ligature points (e.g., hooks or pipes) have been removed.[16]

In Canada, hanging is the most common method of suicide,[17] and in the U.S., hanging is the second most common method, after self-inflicted gunshot wounds.[18] In the United Kingdom, where firearms are less easily available, in 2001 hanging was the most common method among men and the second most commonplace among women (after poisoning).[19]

Those who survive a suicide-via-hanging attempt, whether due to breakage of the cord or ligature point, or being discovered and cut down, face a range of serious injuries, including cerebral anoxia (which can lead to permanent brain damage), laryngeal fracture, cervical spine fracture (which may cause paralysis), tracheal fracture, pharyngeal laceration, and carotid artery injury.[20]

As human sacrifice

[edit]There are some suggestions that the Vikings practised hanging as human sacrifices to Odin, to honour Odin's own sacrifice of hanging himself from Yggdrasil.[21] In Northern Europe, it is widely speculated that the Iron Age bog bodies, many of which show signs of having been hanged, were examples of human sacrifice to the gods.[22]

Medical effects

[edit]

A hanging may induce one or more of the following medical conditions, some leading to death:

- Closure of carotid arteries causing cerebral hypoxia[1]

- Closure of the jugular veins

- Breaking of the neck (cervical fracture) causing traumatic spinal cord injury or even unintended decapitation[23]

- Closure of the airway[1]

The cause of death in hanging depends on the conditions related to the event. When the body is released from a relatively high position, the major cause of death is severe trauma to the upper cervical spine. The injuries produced are highly variable. One study showed that only a small minority of a series of judicial hangings produced fractures to the cervical spine (6 out of 34 cases studied), with half of these fractures (3 out of 34) being the classic "hangman's fracture" (bilateral fractures of the pars interarticularis of the C2 vertebra).[24]

The side, or subaural knot, has been shown to produce other, more complex injuries, with one thoroughly studied case producing only ligamentous injuries to the cervical spine and bilateral vertebral artery disruptions, but no major vertebral fractures or crush injuries to the spinal cord.[25]

In the absence of fracture and dislocation, occlusion of blood vessels becomes the major cause of death, rather than asphyxiation. Obstruction of venous drainage of the brain via occlusion of the internal jugular veins leads to cerebral oedema and then cerebral ischemia. The face will typically become engorged and cyanotic (turned blue through lack of oxygen). Compromise of the cerebral blood flow may occur by obstruction of the carotid arteries, even though their obstruction requires far more force than the obstruction of jugular veins, since they are seated deeper and they contain blood in much higher pressure compared to the jugular veins.[26]

Notable practices across the globe

[edit]

Hanging has been a method of capital punishment in many countries, and is still used by many countries to this day. Long-drop hanging is mainly used by former British colonies, while short-drop and suspension hanging is common elsewhere, in countries including Iran and Afghanistan.

Afghanistan

[edit]Hanging is the most used form of capital punishment in Afghanistan.[citation needed]

Australia

[edit]Capital punishment was a part of the legal system of Australia from the establishment of New South Wales as a British penal colony, until 1985, by which time all Australian states and territories had abolished the death penalty.[27] In practice, the last execution in Australia was the hanging of Ronald Ryan on 3 February 1967, in Victoria.[28]

During the 19th century, crimes that could carry a death sentence included burglary, sheep theft, forgery, sexual assaults, murder and manslaughter. During the 19th century, there were roughly eighty people hanged every year throughout the Australian colonies for these crimes.[citation needed]

Bahamas

[edit]The Bahamas employs hanging to execute the condemned, but no executions have been conducted in the country since 2000.[29] As of 2023, there have been some inmates on death row but their sentences have been commuted.[citation needed]

Bangladesh

[edit]Hanging is the only method of execution in Bangladesh, ever since its independence.[citation needed]

Brazil

[edit]Death by hanging was the customary method of capital punishment in Brazil throughout its history. Some important national heroes like Tiradentes (1792) were killed by hanging. The last man executed in Brazil was the slave Francisco, in 1876.[30] The death penalty was abolished for all crimes, except for those committed under extraordinary circumstances such as war or military law, in 1890.[31]

Bulgaria

[edit]Bulgaria's national hero, Vasil Levski, was executed by hanging by the Ottoman court in Sofia in 1873. Every year since Bulgaria's liberation, thousands come with flowers on the date of his death, 19 February, to his monument where the gallows stood. The last execution was in 1989, and the death penalty was abolished for all crimes in 1998.[31]

Canada

[edit]Historically, hanging was the only method of execution used in Canada and was in use as possible punishment for all murders until 1961, when murders were reclassified into capital and non-capital offences. The death penalty was restricted to apply only for certain offences to the National Defence Act in 1976 and was completely abolished in 1998.[32] The last hangings in Canada took place on 11 December 1962.[31]

Egypt

[edit]In 1955, Egypt hanged three Israelis on charges of spying.[33] In 1982 Egypt hanged three civilians convicted of the assassination of Anwar Sadat.[34] In 2004, Egypt hanged five militants on charges of trying to kill the Prime Minister.[35][not specific enough to verify] To this day, hanging remains the standard method of capital punishment in Egypt, which executes more people each year than any other African country.

Germany

[edit]

In the territories occupied by Nazi Germany from 1939 to 1945, strangulation hanging was a preferred means of public execution, although more criminal executions were performed by guillotine than hanging. The most commonly sentenced were partisans and black marketeers, whose bodies were usually left hanging for long periods. There are also numerous reports of concentration camp inmates being hanged. Hanging was continued in post-war Germany in the British and US Occupation Zones under their jurisdiction, and for Nazi war criminals, until well after (western) Germany itself had abolished the death penalty by the Basic Law (constitution) as adopted in 1949. West Berlin was not subject to the Basic Law and abolished the death penalty in 1951. The German Democratic Republic abolished the death penalty in 1987. The last execution ordered by a West German court was carried out by guillotine in Moabit prison in 1949. The last hanging in Germany was the one ordered of several war criminals in Landsberg am Lech on 7 June 1951. The last known execution in East Germany was in 1981 by a pistol shot to the neck.[27]

Hong Kong

[edit]Even though Hong Kong is now part of China, it has no capital punishment; it is a special administrative region of China. When Hong Kong was still a part of the British Empire, it had hanging as the method of execution. The last person who was executed was a Chinese Vietnamese man who attacked a security guard and another person. This execution occurred in 1966.[36]

Hungary

[edit]The prime minister of Hungary, during the 1956 Revolution, Imre Nagy, was secretly tried, executed by hanging, and buried unceremoniously by the new Soviet-backed Hungarian government, in 1958. Nagy was later publicly exonerated by Hungary.[37] Capital punishment was abolished for all crimes in 1990.[27]

India

[edit]

Hanging was introduced by the British. All executions in India since independence have been carried out by hanging, although the law provides for military executions to be carried out by firing squad. In 1949, Nathuram Godse, who had been sentenced to death for the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, was the first person to be executed by hanging in independent India.[38]

The Supreme Court of India has suggested that capital punishment should be given only in the "rarest of rare cases".[39]

Since 2001, eight people have been executed in India.

- Dhananjoy Chatterjee, convicted for rape and murder in 1991, was executed on 14 August 2004 in Alipore Jail, Kolkata.

- Ajmal Kasab, the lone surviving terrorist of the 2008 Mumbai attacks, was executed on 21 November 2012 in Yerwada Central Jail, Pune. The Supreme Court of India had previously rejected his mercy plea, which was then rejected by the President of India. He was hanged one week later.

- Afzal Guru, a terrorist found guilty of conspiracy in the December 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament, was executed by hanging in Tihar Jail, Delhi on 9 February 2013.

- Yakub Memon was convicted over his involvement in the 1993 Bombay bombings by the Special Terrorist and Disruptive Activities court on 27 July 2007. His appeals and petitions for clemency were all rejected and he was finally executed by hanging on 30 July 2015 in Nagpur jail.

- On 20 March 2020, four prisoners named Pawan Gupta, Vinay Sharma, Mukesh Singh and Akshay Thakur who were convicted in the 2012 Delhi gang rape and murder case were executed by hanging in Tihar Jail.[40]

Iran

[edit]Hanging is the most used form of capital punishment in Iran.[41]

Iraq

[edit]Hanging was used under the regime of Saddam Hussein,[42][self-published source] but was suspended along with capital punishment on 10 June 2003, when a coalition led by the United States invaded and overthrew the previous regime. The death penalty was reinstated on 8 August 2004.[43]

In September 2005, three murderers were the first people to be executed since the restoration. Then on 9 March 2006, an official of Iraq's Supreme Judicial Council confirmed that Iraqi authorities had executed the first insurgents by hanging.[44]

Saddam Hussein was sentenced to death by hanging for crimes against humanity[45] on 5 November 2006, and was executed on 30 December 2006 at approximately 6:00 a.m. local time. During the drop, there was an audible crack indicating that his neck was broken, a successful example of a long-drop hanging.[46]

Barzan Ibrahim, the head of the Mukhabarat, Saddam's security agency, and Awad Hamed al-Bandar, former chief judge, were executed on 15 January 2007, also by the long-drop method, but Barzan was decapitated by the rope at the end of his fall.[47][48]

Former vice-president Taha Yassin Ramadan had been sentenced to life in prison on 5 November 2006, but the sentence was changed to death by hanging on 12 February 2007.[49] He was the fourth and final man to be executed for the 1982 crimes against humanity on 20 March 2007. The execution went smoothly.[50]

At the Anfal genocide trial, Saddam's cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid (nicknamed Chemical Ali by Iraqis), former defence minister Sultan Hashim Ahmed al-Tay, and former deputy Hussein Rashid Mohammed were sentenced to hang for their role in the Al-Anfal Campaign against the Kurds on 24 June 2007.[51] Al-Majid was sentenced to death three more times: once for the 1991 suppression of a Shi'a uprising along with Abdul-Ghani Abdul Ghafur on 2 December 2008;[52] once for the 1999 crackdown in the assassination of Grand Ayatollah Mohammad al-Sadr on 2 March 2009;[53] and once on 17 January 2010 for the gassing of the Kurds in 1988;[54] he was hanged on 25 January.[55]

On 26 October 2010, Saddam's top minister Tariq Aziz was sentenced to hang for persecuting the members of rival Shi'a political parties.[56] His sentence was commuted to indefinite imprisonment after Iraqi president Jalal Talabani did not sign his execution order and he died in prison in 2015.

On 14 July 2011, US forces transferred condemned prisoners Sultan Hashim Ahmad al-Tai and two of Saddam's half-brothers, Sabawi Ibrahim al-Tikriti and Watban Ibrahim al-Tikriti, to Iraqi authorities for execution.[57] The Iraqi High Tribunal had sentenced Saddam's half-brothers to death on 11 March 2009 for their roles in the executions of 42 traders who were accused of manipulating food prices.[58] None of the three men were executed.[59][60][61]

It is alleged that Iraq's government keeps the execution rate secret, and hundreds may be carried out every year. In 2007, Amnesty International stated that 900 people were at "imminent risk" of execution in Iraq.

Israel

[edit]Israel has provisions in its criminal law to use the death penalty for extraordinary crimes. It has been used only twice for Israelis, and only one of those executions was by hanging. On 31 May 1962, Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann was executed by hanging after having been captured in Argentina in May 1960, taken to Israel and tried and sentenced to death.[31][62]

Japan

[edit]All executions in Japan are carried out by hanging.

On 23 December 1948, Hideki Tojo, Kenji Doihara, Akira Mutō, Iwane Matsui, Seishirō Itagaki, Kōki Hirota, and Heitaro Kimura were hanged at Sugamo Prison by the U.S. occupation authorities in Ikebukuro in Allied-occupied Japan for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against peace during the Asian-Pacific theatre of World War II.[63][unreliable source?][64][self-published source]

On 27 February 2004, the mastermind of the Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, Shoko Asahara, was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. On 25 December 2006, serial killer Hiroaki Hidaka and three others were hanged in Japan. Long-drop hanging is the method of carrying out judicial capital punishment on civilians in Japan, as in the cases of Norio Nagayama,[65] Mamoru Takuma,[66] and Tsutomu Miyazaki.[67] In 2018 Shoko Asahara and several of his cult members were hanged for committing the 1995 sarin gas attack.

Jordan

[edit]Hanging is the traditional method of capital punishment in Jordan. On 14 August 1993, Jordan hanged two Jordanians convicted of spying for Israel.[68] Sajida al-Rishawi, the "4th bomber" of the 2005 Amman bombings, was executed by hanging alongside Ziad al-Karbouly on 4 February 2015, while she was in the process of appealing her sentence for terrorism offences, in retribution for the immolation of Jordanian pilot Muath Al-Kasasbeh.

Kuwait

[edit]Kuwait has always used hanging for execution. During the Gulf War, Iraqi government officials executed different people for different reasons. After the war, Kuwait hanged Iraqi collaborators.[69][full citation needed] Sometimes the executions are in public. The most recent executions were in 2022.[70]

Lebanon

[edit]Lebanon hanged two men in 1998 for murdering a man and his sister.[71] However, capital punishment ended up being altogether suspended in Lebanon, as a result of staunch opposition by activists and some political factions.[72]

Liberia

[edit]

On 16 February 1979, seven men convicted of the ritual killing of Kru traditional singer Moses Tweh were publicly hanged at dawn in Harper.[73][74]

Malaysia

[edit]Hanging is the traditional method of capital punishment in Malaysia and has been used to execute people convicted of murder, drug trafficking and waging war against the government. The Barlow and Chambers execution was carried out as a result of new tighter drug regulations.

Pakistan

[edit]In Pakistan, hanging is the most common form of execution.

Portugal

[edit]The last person executed by hanging in Portugal was Francisco Matos Lobos on 16 April 1842. Before that, it had been a common death penalty.

Russia

[edit]Hanging was commonly practised in the Russian Empire during the rule of the Romanov dynasty as an alternative to impalement, which was used in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Hanging was abolished in 1868 by Alexander II after serfdom,[clarification needed] but was restored by the time of his death and his assassins were hanged. While those sentenced to death for murder were usually pardoned and sentences commuted to life imprisonment, those guilty of high treason were usually executed. This also included the Grand Duchy of Finland and Kingdom of Poland under the Russian crown. Taavetti Lukkarinen became the last Finn to be executed this way. He was hanged for espionage and high treason in 1916.

The hanging was usually performed by short drop in public. The gallows were usually either a stout nearby tree branch, as in the case of Lukkarinen, or a makeshift gallows constructed for the purpose.

After the October Revolution in 1917, capital punishment was, on paper, abolished, but continued to be used unabated against people perceived to be enemies of the regime. Under the Bolsheviks, most executions were performed by shooting, either by firing squad or by a single firearm. In 1943, hanging was restored primarily for German servicemen and native collaborators for atrocities committed against Soviet POWs and civilians. The last to be hanged were Andrey Vlasov and his companions in 1946.

Singapore

[edit]In Singapore, long-drop hanging[14] is currently used as a mandatory punishment for crimes such as drug trafficking, murder and some types of kidnapping. It was introduced by the British, when they occupied Singapore and neighbouring Malaysia. It has also been used for punishing those convicted of unauthorised discharging of firearms.[75]

Sri Lanka

[edit]Hanging was abolished in Sri Lanka in 1956, but in 1959 it was brought back and later halted in 1978. In 1975, the day before the execution of Maru Sira, he had been overdosed by the prison guards to prevent him from escaping. On the day of his execution he was unconscious, so when he was brought to the gallows, he was slumped over on the trapdoor with a noose around his neck, and when the executioner pulled the lever, his execution was botched and he strangled.

Syria

[edit]

Syria has publicly hanged people, such as two individuals in 1952, Israeli spy Eli Cohen in 1965, and a number of Jews accused of spying for Israel in 1969.[76][77][78]

According to a 19th-century report, members of the Alawite sect centred on Lattakia in Syria had a particular aversion towards being hanged, and the family of the condemned was willing to pay "considerable sums" to ensure its relations were impaled, instead of being hanged. As far as Burckhardt could make out, this attitude was based upon the Alawites' idea that the soul ought to leave the body through the mouth, rather than leave it in any other fashion.[79]

The Islamic State also used hanging post-mortem, after they executed alleged spies for the western-backed coalition in Deir ez-Zor by cutting their throats in a slaughterhouse, during the Islamic holiday of Eid al-Adha in 2016. They also used shooting, beheading, fire and other methods to execute people during their rule.[citation needed]

United Kingdom

[edit]As a form of judicial execution in England, hanging is thought to date from the Anglo-Saxon period.[80] Records of the names of British hangmen begin with Thomas de Warblynton in the 1360s;[citation needed] complete records extend from the 16th century to the last hangmen, Robert Leslie Stewart and Harry Allen, who conducted the last British executions in 1964.

Until 1868 hangings were performed in public. In London, the traditional site was at Tyburn, a settlement west of the City on the main road to Oxford, which was used on eight hanging days a year, though before 1865, executions had been transferred to the street outside Newgate Prison, Old Bailey, now the site of the Central Criminal Court.

Three British subjects were hanged after World War II after having been convicted of having helped Nazi Germany in its war against Britain. John Amery, the son of prominent British politician Leo Amery, became an expatriate in the 1930s, moving to France. He became involved in pre-war fascist politics, remained in what became Vichy France following France's defeat by Germany in 1940 and eventually went to Germany and later the German puppet state in Italy headed by Benito Mussolini. Captured by Italian partisans at the end of the war and handed over to British authorities, Amery was accused of having made propaganda broadcasts for the Nazis and of having attempted to recruit British prisoners of war for a Waffen SS regiment later known as the British Free Corps. Amery pleaded guilty to treason charges on 28 November 1945[81] and was hanged at Wandsworth Prison on 19 December 1945. William Joyce, an American-born Irishman who had lived in Britain and possessed a British passport, had been involved in pre-war fascist politics in the UK, fled to Nazi Germany just before the war began to avoid arrest by British authorities and became a naturalised German citizen. He made propaganda broadcasts for the Nazis, becoming infamous under the nickname Lord Haw-Haw. Captured by British forces in May 1945, he was tried for treason later that year. Although Joyce's defence argued that he was by birth American and thus not subject to being tried for treason, the prosecution successfully argued that Joyce's pre-war British passport meant that he was a subject of the British Crown and he was convicted. After his appeals failed, he was hanged at Wandsworth Prison on 3 January 1946.[82] Theodore Schurch, a British soldier captured by the Nazis who then began working for the Italian and German intelligence services by acting as a spy and informer who would be placed among other British prisoners, was arrested in Rome in March 1945 and tried under the Treachery Act 1940. After his conviction, he was hanged at HM Prison Pentonville on 4 January 1946.

The Homicide Act 1957 created the new offence of capital murder, punishable by death, with all other murders being punishable by life imprisonment.

In 1965, Parliament passed the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act, temporarily abolishing capital punishment for murder for five years. The Act was renewed in 1969, making the abolition permanent. With the passage of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 and the Human Rights Act 1998, the death penalty was officially abolished for all crimes in both civilian and military cases. Following its complete abolition, the gallows were removed from Wandsworth Prison, where they remained in full working order until that year.

The last woman to be hanged was Ruth Ellis on 13 July 1955, by Albert Pierrepoint who was a prominent hangman in the 20th century in England. The last hangings in Britain took place in 1964, when Peter Anthony Allen was executed at Walton Prison in Liverpool. Gwynne Owen Evans was executed by Harry Allen at Strangeways Prison in Manchester. Both were executed for the murder of John Alan West.[83]

Hanging was also the method used in many colonies and overseas territories.[84]

Silken rope

[edit]In the UK, some felons are traditionally said to have been executed by hanging with a silken rope:

- Hereditary peers who committed capital offences,[85] as anticipated by the fictional Duke of Denver, brother of Lord Peter Wimsey. The Duke was accused of murder in the novel Clouds of Witness, and this execution would have been his fate, after conviction by his peers in a trial in the House of Lords. It has been claimed that the execution of Earl Ferrers in 1760 – the only time a peer was hanged after trial by the House of Lords – was carried out with the normal hempen rope instead of a silk one. The writ of execution does not specify a silk rope be used,[86] and The Newgate Calendar makes no mention of the use of such an item[87] – an unusual omission given its highly sensationalist nature.

- Those who have the Freedom of the City of London.[88]

-

An image of suspected witches being hanged in England, published in 1655

-

Balvenie Pillar, also known as Tom na Croiche (Hangman's Knoll, lit. 'Tom of the Cross'). The pillar was erected in 1755 to commemorate the last public hanging in the Atholl region of Scotland in 1630.

-

Hanging noose used at public executions outside Lancaster Castle, c. 1820s–1830s.

United States

[edit]

Hanging was one means by which Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony enforced religious and intellectual conformity on the whole community.[89] The best known hanging carried out by the Puritans, Mary Dyer, was one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs.[90]

The United States is the only Western democracy[clarification needed] that still allows the government to execute people. However, the use of capital punishment in the U.S. varies widely from state to state; it is outlawed in nearly half of the states but used in several others along with the federal system. The death penalty under federal law is applicable in every state, and the Donald Trump administration since 2019 has been unswerving in its desire to carry out as many federal executions as possible and federalize capital crimes to cover even state-level offenses in states without a death penalty of their own (such as New York). However, no federal hangings have taken place yet. Hanging is only used at the state level in Florida as of 2025. Previously, the last state to allow hanging as a method of execution, New Hampshire, abolished the death penalty in 2019.

In July 2025, Florida enacted legislation that further expands the state's already extensive capital punishment laws to allow "any execution method not explicitly deemed unconstitutional," which includes hanging. This makes the United States the only country in the Western world that currently allows executions via hanging.[91][92]

When African American pastor Denmark Vesey of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church was suspected of plotting to launch a slave rebellion in Charleston, South Carolina in 1822, 35 people, including Vesey, were judged guilty by a city-appointed court and were subsequently hanged, and the church was burned down.[93]

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Dakota uprising, led to the largest mass execution in the United States when 38 Sioux Indians, who were facing starvation and displacement, attacked white settlers, for which they were sentenced to death via hanging in Mankato, Minnesota in December 1862.[94] Originally, 303 had been sentenced to hang, but the convictions were reviewed by President Abraham Lincoln and the sentences of all but 38 were commuted.[95] In 2019, Governor Tim Walz issued an historic apology to the Dakota people for the mass hanging and the "trauma inflicted on Native people at the hands of state government".[94]

A total of 40 suspected Unionists were hanged in Gainesville, Texas, in October 1862.[96] On 7 July 1865, four people involved in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln—Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt—were hanged at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C.

While relatively uncommon, hanging in chains has also been practiced (mainly during the colonial era), the first being a slave after the New York Slave Revolt of 1712. The last hanging in chains was in 1913, of John Marshall in West Virginia for murder.[97] The last public hanging in the United States (not including lynching, one of the last of which was Michael Donald in 1981) took place on 14 August 1936, in Owensboro, Kentucky. Rainey Bethea was executed for the rape and murder of 70-year-old Lischa Edwards. The execution was presided over by the first female sheriff in Kentucky, Florence Shoemaker Thompson.[98][99]

In California, Clinton Duffy, who served as warden of San Quentin State Prison between 1940 and 1952, presided over ninety executions.[100] He began to oppose the death penalty, and after his retirement, wrote a memoir entitled Eighty-Eight Men and Two Women in support of the movement to abolish the death penalty. The book documents several hangings gone wrong and describes how they led his predecessor, Warden James B. Holohan, to persuade the California Legislature to replace hanging with the gas chamber in 1937.[101][102]

Various methods of capital punishment have been replaced by lethal injection in most states and the federal government. Many states that offered hanging as an option have since eliminated the method. Condemned murderer Victor Feguer became the last inmate to be executed by hanging in the state of Iowa on 15 March 1963. Hanging was the preferred method of execution for capital murder cases in Iowa until 1965, when the death penalty was abolished and replaced with life imprisonment without parole. Barton Kay Kirkham was the last person to be hanged in Utah, preferring it over execution by firing squad. Laws in Delaware were changed in 1986 to specify lethal injection, except for those convicted before 1986 (who were still allowed to choose hanging). If a choice was not made, or the convict refused to choose injection, then hanging would become the default method. This was the case in the 1996 execution of Billy Bailey, the most recent hanging in American history; since then, no Delaware prisoner fit the category, and the state's gallows were later dismantled.

Upright jerker

[edit]The upright jerker is a method of hanging that originated in the United States in the late 19th century. The person to be hanged is jerked into the air by weights and pulleys. It proved to be ineffective at breaking the neck of the condemned, and death by asphyxiation often occurred instead. In the United States, use of the method ceased in the late 1930s.

Inverted hanging, the "Jewish" punishment

[edit]

A completely different principle of hanging is to hang the convicted person from their legs, rather than from their neck, either as a form of torture, or as an execution method. In late medieval Germany, this came to be primarily associated with Jews accused of being thieves, called the Judenstrafe (lit. 'Jewish punishment'). The jurist Ulrich Tengler, in his Layenspiegel from 1509, describes the procedure as follows, in the section "Von Juden straff" ("On the punishment of Jews"):[103]

To drag the Jew to the ordinary execution place between two angry or biting dogs. After dragging, to hang him from his feet by rope or chain at a designated gallows between the dogs, so that he is directed from life to death[104]

Guido Kisch showed that originally, this type of inverted hanging between two dogs was not a punishment specifically for Jews. Esther Cohen writes:[105]

The inverted hanging with the accompaniment of two dogs, originally reserved for traitors, was identified from the fourteenth century as the "Jewish execution", being practised in the later Middle Ages in both northern and Mediterranean Europe. The Jewish execution in Germany has been thoroughly studied by G. Kisch, who has argued convincingly that neither the inverted hanging nor the stringing up of dogs or wolves beside the victim were particularly Jewish punishments during the High Middle Ages. They first appeared as Jewish punishments in Germany only towards the end of the thirteenth century, never being recognized as exclusively Jewish penalties.

In France the inverted, animal-associated hanging came to be connected with Jews by the later Middle Ages. The inverted hanging of Jews is specifically mentioned in the old customs of Burgundy in the context of animal hanging. The custom, dogs and all, was still in force in Paris shortly before the final expulsion of the Jews in 1394.

In Spain 1449, during a mob attack against the Marranos (Jews nominally converted to Christianity), the Jews resisted, but lost and several of them were hanged up by the feet.[106] The first attested German case for a Jew being hanged by the feet is from 1296, in present-day Soultzmatt.[107] Some other historical examples of this type of hanging within the German context are one Jew in Hennegau 1326, two Jews hanged in Frankfurt in 1444,[108] one in Halle in 1462,[109] one in Dortmund in 1486,[110] one in Hanau in 1499,[108] one in Breslau in 1505,[111] one in Württemberg in 1553,[112] one in Bergen in 1588,[108] one in Öttingen in 1611,[113] one in Frankfurt in 1615 and again in 1661,[108] and one condemned to this punishment in Prussia in 1637.[114]

The details of the cases vary widely: In the 1444 Frankfurt cases and the 1499 Hanau case, the dogs were dead prior to being hanged, and in the late 1615 and 1661 cases in Frankfurt, the Jews (and dogs) were merely kept in this manner for half an hour, before being garroted from below. In the 1588 Bergen case, all three victims were left hanging till they were dead, ranging from 6 to 8 days after being hanged. In the Dortmund 1486 case, the dogs bit the Jew to death while hanging. In the 1611 Öttingen case, the Jew "Jacob the Tall" thought to blow up the Deutsche Ordenhaus with gunpowder after having burgled it. He was strung up between two dogs, and a large fire was made close by, and he expired after half an hour under this torture. In the 1553 Württemberg case, the Jew chose to convert to Christianity after hanging like this for 24 hours; he was then given the mercy to be hanged in the usual manner, from the neck, and without the dogs beside him. In the 1462 Halle case, the Jew Abraham also converted after 24 hours hanging upside down, and a priest ascended a ladder to baptise him. For two more days, Abraham was left hanging, while the priest argued with the city council that a true Christian should not be punished in this way. On the third day, Abraham was granted a reprieve, taken down, but died 20 days later in the local hospital having meanwhile suffered in extreme pain. In the 1637 case, where the Jew had murdered a Christian jeweller, the appeal to the empress was successful, and out of mercy, the Jew was condemned to be merely pinched with glowing pincers, have hot lead dripped into his wounds, and then be broken alive on the wheel.

Some of the reported cases may be myths, or wandering stories. The 1326 Hennegau case, for example, deviates from the others in that the Jew was not a thief, but was suspected (though he was a convert to Christianity) of having struck a fresco of the Virgin Mary, so that blood seeped down the wall from the painting. Even under all degrees of judicial torture, the Jew denied performing this sacrilegious act, and was therefore exonerated. Then a brawny smith demanded from him a trial by combat, claiming he dreamt the Virgin herself had urged him to do so. The court accepted the smith's challenge, and he easily won the combat against the Jew, who was duly hanged up by the feet between two dogs. To add to the injury, one let him be slowly roasted as well as hanged.[115] This is a very similar story to one told in France, in which a young Jew threw a lance at the head of a statue of the Virgin, so that blood spurted out of it. There was inadequate evidence for a normal trial, but a frail old man asked for trial by combat, and bested the young Jew. The Jew confessed his crime, and was hanged by his feet between two mastiffs.[116]

The features of the earliest attested case, that of a Jewish thief hanged by the feet in Soultzmatt in 1296 are also rather divergent from the rest. The Jew managed somehow, after he had been left to die, to twitch his body in such a manner that he could hoist himself up on the gallows and free himself. At that time, his feet were so damaged that he was unable to escape, and when he was discovered 8 days after he had been hanged, he was strangled to death by the townspeople.[117]

As late as in 1699 in Celle, the courts were sufficiently horrified at how the Jewish leader of a robber gang (condemned to be hanged in the normal manner) declared blasphemies against Christianity, that they made a ruling on the post mortem treatment of Jonas Meyer. After three days, his corpse was cut down, his tongue cut out, and his body was hanged up again, but this time from its feet.[118]

Punishment for traitors

[edit]Guido Kisch writes that the first instance he knows where a person in Germany was hanged up by his feet between two dogs until he died occurred about 1048, some 250 years earlier than the first attested Jewish case. This was a knight called Arnold, who had murdered his lord; the story is contained in Adam of Bremen's History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen.[119] Another example of a non-Jew who suffered this punishment as a torture, in 1196 Richard, Count of Acerra, was one of those executed by Henry VI in the suppression of the rebelling Sicilians:[120]

He [Henry VI] held a general court in Capua, at which he ordered that the count first be drawn behind a horse through the squares of Capua, and then hanged alive head downwards. The latter was still alive after two days when a certain German jester called Leather-Bag [Follis], hoping to please the emperor, tied a large stone to his neck and shamefully put him to death

A couple of centuries earlier, in France in 991, a certain viscount Walter nominally owing his allegiance to the French King Hugh Capet chose, on instigation of his wife, to join the rebellion under Odo I, Count of Blois. When Odo found out he had to abandon Melun after all, Walter was duly hanged before the gates, whereas his wife, the fomentor of treason, was hanged by her feet, causing much merriment and jeers from Hugh's soldiers as her clothes fell downwards revealing her naked body, although it is not wholly clear if she died in that manner.[121]

Elizabethan maritime law

[edit]During Queen Elizabeth I's reign, the following was written concerning those who stole a ship from the Royal Navy:[122]

If anye one practysed to steale awaye anye of her Majesty's shippes, the captaine was to cause him to be hanged by the heels untill his braines were beaten out against the shippe's sides, and then to be cutt down and lett fall intoe the sea.

Translation into modern English: If anyone practised to steal away any of Her Majesty's ships, the captain was to cause him [the thief] to be hanged by the heels until his brains were beaten out against the ship's sides, and then to be cut down and let fall into the sea.

Hanging by the ribs

[edit]

In 1713, Juraj Jánošík, a semi-legendary Slovak outlaw and folk hero, was sentenced to be hanged from his left rib. He was left to slowly die.[123]

The German physician Gottlob Schober (1670–1739),[124] who worked in Russia from 1712, noted that a person could hang from the ribs for about three days prior to dying, with his primary pain being that of extreme thirst. He thought this degree of insensitivity was something peculiar to the Russian mentality.[125]

The Dutch in Suriname were also in the habit of hanging a slave from the ribs, a custom amongst the African tribes from whom they were originally purchased. John Gabriel Stedman stayed in South America from 1772 to 1777 and described the method as told by a witness:[126]

"Not long ago," (continued he) "I saw a black man suspended alive from a gallows by the ribs, between which, with a knife, was first made an incision, and then clinched an iron hook with a chain: in this manner he kept alive three days, hanging with his head and feet downwards, and catching with his tongue the drops of water (it being in the rainy season) that were flowing down his bloated breast. Notwithstanding all this, he never complained, and even upbraided a negro for crying while he was flogged below the gallows, by calling out to him: 'You man?—Da boy fasy? Are you a man? you behave like a boy.' Shortly after which he was knocked on the head by the commiserating sentry, who stood over him, with the butt end of his musket."

William Blake was specially commissioned to make illustrations to Stedman's narrative.[127]

Grammar

[edit]The standard past tense and past participle form of the verb "hang", in the sense of this article, is "hanged",[128][129][130] although some dictionaries give "hung" as an alternative.[131][132]

See also

[edit]- Capital punishment

- Death erection

- Dule tree

- Erotic asphyxiation

- Executioner

- Gallows

- Garrote

- Hand of Glory

- Hanging judge

- Hanging tree (United States)

- Hangman (game)

- Hangman's knot

- Jack Ketch

- List of people who died by hanging

- List of suicides

- Lynching

- Lynching in the United States

- Suicide by hanging

- Rope

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Mahmoud Rayes; Monika Mittal; Setti S. Rengachary; Sandeep Mittal (February 2011). "Hangman's fracture: a historical and biomechanical perspective" (PDF). Journal of Neurosurgery. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

It was not until the introduction of the standard drop by Dr. Samuel Haughton in 1866, and the so-called long drop by William Marwood in 1872 that hanging became a standard, humane means to achieve instantaneous death.

- ^ Hughes, Robert (11 January 2012). The Fatal Shore: The epic of Australia's founding. Knopf Doubleday. pp. 33ff. ISBN 978-0-307-81560-6. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

Before the invention of the hinged trapdoor through which the victim was dropped, he or she was 'turned off' or 'twisted' by the hangman who pulled the ladder away.

- ^ Potter, John Deane (1965). The Art of Hanging. A. S. Barnes. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-498-07387-8. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

... condemned persons still mounted a ladder which was turned round, leaving them dangling. This led to the phrase 'turned off'—they were literally turned off the ladder.

- ^ Sauvageau, Anny; Racette, Stéphanie (2007). "Agonal Sequences in a Filmed Suicidal Hanging: Analysis of Respiratory and Movement Responses to Asphyxia by Hanging". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 52 (4): 957–959. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00459.x. PMID 17524058. S2CID 32188375.

- ^ "Olga Hepnarová - The Last Woman Executed in Czechoslovakia". Capital Punishment UK. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "1946: Karl Hermann Frank". Executedtoday.com. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "How Does Death by Hanging Work?". How Stuff Works. 4 January 2007. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ Hellier, C.; Connolly, R. (2009). "Cause of death in judicial hanging: a review and case study". Medicine, Science, and the Law. 49 (1): 18–26. doi:10.1258/rsmmsl.49.1.18. PMID 19306616. S2CID 34469210.

- ^ Report by Kingsbury Smith, International News Service, 16 October 1946.

- ^ MacDonogh G., After the Reich John Murray, London (2008) p. 450.

- ^ "The Gallows Chamber". Life, 28 October 1946. Archived 12 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "History of British judicial hanging". Capital Punishment UK. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Pierrepoint, Albert (1989). Executioner: Pierrepoint. Hodder & Stoughton General Division. ISBN 978-0-340-21307-0.

- ^ a b "'Seven days of horror and hope': What happens during someone's last days on death row in Singapore". Coconuts. 25 April 2023. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "Politics and capital punishment a volatile mixture". Japan Times. 23 June 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ Bennewith, Olive; Gunnell, David; Kapur, Navneet; Turnbull, Pauline; Simkin, Sue; Sutton, Lesley; Hawton, Keith (2 January 2018). "Suicide by hanging: multicentre study based on coroners' records in England". British Journal of Psychiatry. 186 (3): 260–261. doi:10.1192/bjp.186.3.260. PMID 15738509.

- ^ "Canadian Injury Data". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 1 October 2005.

- ^ "Suicide Statistics". Archived from the original on 18 April 2006. Retrieved 16 May 2006.

- ^ "Trends in suicide by method in England and Wales, 1979 to 2001" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2006.

- ^ "ResearchGate – Share and discover research". Researchgate.net. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Simek, Rudolf (2007). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Angela Hall. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-513-7.

- ^ Glob, P (2004). The Bog People: Iron-Age Man Preserved. New York: New York Review of Books. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-59017-090-8.

- ^ Nothaft, Mark (1 November 2017). "Horrific tale of Eva Dugan caused Arizona to change death by hanging". Arizona Republic. Retrieved 22 October 2025.

- ^ James R, Nasmyth-Jones R., "The occurrence of cervical fractures in victims of judicial hanging", Forensic Science International, April 1992; 54(1):81–91.

- ^ Wallace SK, Cohen WA, Stern EJ, Reay DT, "Judicial hanging: postmortem radiographic, CT, and MR imaging features with autopsy confirmation", Radiology, October 1994; 193(1):263–7.

- ^ "How hanging causes death". Archived from the original on 26 April 2006. Retrieved 27 April 2006.

- ^ a b c "Countries that have abandoned the use of the death penalty". . Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance, 8 November 2005

- ^ "Death penalty in Australia". Archived 29 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine, New South Wales Council for Civil Liberties

- ^ "David Mitchell Put to Death 23 Years Ago". 7 January 2023.

- ^ Decolonizing the Criminal Question. Oxford University Press. 2023. p. 204.

- ^ a b c d "Capital Punishment Worldwide". Archived 1 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine. MSN Encarta.

- ^ Susan Munroe, "History of Capital Punishment in Canada". Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. About: Canada Online.

- ^ Bennis, Phyllis (2003). Before and After. Olive Branch Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-56656-462-5.

- ^ "Sadat Assassins are Executed". The Glasgow Herald. 16 April 1982. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ "Articles about Egypt - Page 2 - New York Times". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ "Demise of the death penalty". South China Morning Post. 23 March 2004.

- ^ Richard Solash (20 June 2006), "Hungary: U.S. President To Honor 1956 Uprising". Archived 9 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- ^ "Yakub Memon first to be hanged in Maharashtra after Ajmal Kasab". The Indian Express. 30 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Sakhrani, Monica; Adenwalla, Maharukh. "Death Penalty – Case for Its Abolition". Economic & Political Weekly. Archived from the original on 17 August 2005.

- ^ hanged to death, Nirbhaya convicts (20 March 2020). "Four Nirbhaya case convicts hanged to death in Tihar jail". The Hindu. The Hindu Newspaper. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Iran executes 29 in jail hangings". BBC News. 27 July 2008. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Clark, Richard. "The process of Judicial Hanging". Capital Punishment U.K. Archived from the original on 9 August 2002. Retrieved 29 December 2005.

- ^ "Scores face execution in Iraq six years after invasion". Amnesty International USA. 20 March 2009. Archived from the original on 13 May 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- ^ "More bombs bring death to Iraq". Mail & Guardian Online. 10 March 2006. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2006.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein sentenced to death by hanging". CNN. 5 November 2006. Archived from the original on 13 November 2006. Retrieved 5 November 2006.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein Hanging Video Shows Defiance, Taunts and Glee". The National Ledger. 1 January 2007. Archived from the original on 20 January 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- ^ Burns, John F. (15 January 2007). "Two Hussein Allies Are Hanged; One Is Decapitated". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ Tarabay, Jamie (15 January 2007). "Saddam's Half-Brother Decapitated During Hanging". NPR. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ "Top Saddam aide sentenced to hang". BBC News. 12 February 2007. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "Former Saddam aide buried after hanging". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 22 March 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ "Iraq's 'Chemical Ali' sentenced to death", MSNBC, 24 June 2007. Retrieved on 24 June 2007.

- ^ "Second death sentence for Iraq's 'Chemical Ali'", MSNBC, 2 December 2008. Retrieved on 2 December 2008.

- ^ "Iraq's 'Chemical Ali' gets 3rd death sentence". Archived 22 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press, 2 March 2009. Retrieved on 17 January 2010.

- ^ "'Chemical Ali' gets a new death sentence". MSNBC, 17 January 2010. Retrieved on 17 January 2010.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein's Henchman Chemical Ali Executed". The Daily Telegraph. London. 25 January 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ Caulfield, Philip (26 October 2010). "Tariq Aziz, Saddam Hussein's former aid, sentenced to hang in Iraq for crimes against humanity". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ al-Ansary, Khalid (15 July 2011). "U.S. turns Saddam's half-brothers over to Iraq". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ "Saddam's deputy PM Tariq Aziz gets 15-year prison sentence". CBC News. 11 March 2009. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Sultan Hashim: Saddam's top general dies in Iraqi prison". The National. 21 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein's half-brother dies of cancer". ABC News. Agence France-Presse. 8 July 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ "Watban Ibrahim al-Hassan, half brother of Saddam Hussein, has died". Iraqi News. 13 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ Arendt, Hannah (1977). Eichmann in Jerusalem. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 240–241, 249–250.

- ^ "Japanese war criminals hanged in Tokyo – Dec 23, 1948". History. 9 February 2010. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "1948: Hideki Tojo and six other Japanese war criminals". Executed Today. 23 December 2008. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "In Secrecy, Japan Hangs a Best-Selling Author, a Killer of 4". The New York Times. 7 August 1997. Archived from the original on 18 February 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ "Japanese school killer executed". BBC News. 14 September 2004. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ "Reports: Japan executes man convicted of killing and mutilating young girls in 1980s". International Herald Tribune. 17 June 2008. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ "Jordan 'hangs Israeli spies'". The Independent. London. 16 August 1993. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Suspected Iraqi collaborators being executed in Kuwait Human rights official says up to 3,000 people are unaccounted for". Baltimore Sun. 19 March 1991.

- ^ "Kuwait hangs seven people in first executions since 2017". Al Jazeera. 16 November 2022.

- ^ "Lebanon executes 2 for 1995 murders". The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. 20 May 1998. p. 2. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2025 – via Google News.

- ^ "LEBANON: Stakeholder Submission to the United Nations Universal Periodic Review" (PDF). The Advocates for Human Rights. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "The Maryland Ritual Murders. The Final Verdict: Death By Hanging". Archived 25 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Liberia: Past and Present. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ "Ritualistic Killings Spark Mob Action in Maryland". Archived 30 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine. The Perspective. January 2005. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ "Singapore clings to death penalty". South Africa: Sunday Times. 21 November 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2006.

- ^ Thomas, Baylis (1999). How Israel was Won: A Concise History of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Lexington Books. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-7391-0064-6.

- ^ Bard, Mitchell G. (2 September 2008). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Middle East Conflict (4th ed.). DK. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-101-21720-7. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Brown, Michael L. (1992). Our Hands Are Stained with Blood. Destiny Image. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-56043-068-1.

- ^ Burckhardt, J. L. (1922). Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. London: John Murray. p. 156.

- ^ Craies, William Feilden (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 917–918.

- ^ "Renegade Amery to Die – Trial Lasted 8 Minutes". Toronto Daily Star. British United Press. 28 November 1945. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2017 – via Google News.

- ^ Newman, Helen (1998). Germany calling! Germany calling! The Influence of Lord Haw-Haw (William Joyce) in Britain, 1939–1941 (BA thesis). Monash University. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017 – via Bernard Safran Paintings.

- ^ Fielding, Steve (2008), The Executioner's Bible, John Blake, ISBN 978-1-84454-648-0

- ^ "The death penalty in the British Commonwealth". Capital Punishment UK. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Lord Williams of Mostyn, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Home Affairs (12 February 1998). "Abolition of death penalty for treason and piracy, etc". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Lords. col. 1350.

The noble Lord, Lord Henley, asked me about the privilege of being hanged with a silken rope. That was discriminatory, because it applied to hereditary Peers only.

- ^ Tiersma, Peter. "Writ of Execution". Language and Law. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "Laurence, Earl Ferrers". The Newgate Calendar. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2017 – via The Ex-Classics Web Site.

- ^ "History". City of London. 30 April 2004. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Merrill, Louis Taylor (1945). "The Puritan Policeman". American Sociological Review. 10 (6). American Sociological Association: 766–776. doi:10.2307/2085847. JSTOR 2085847.

- ^ Rogers, Horatio (2009). Mary Dyer of Rhode Island: The Quaker Martyr That Was Hanged on Boston. Archived 15 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. pp. 1–2. BiblioBazaar.

- ^ "10 of the worst state laws going into effect in July". 30 June 2025.

- ^ "House Bill 903 (2025) - the Florida Senate".

- ^ Smith, Glenn; Boughton, Melissa; Behre, Robert (17 June 2015). "Nine dead after 'hate crime' shooting at Emanuel AME". The Post and Courier. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Governor Walz makes historic apology for 1862 mass hanging in Mankato". Indian Country Today (Press release). Office of Governor Tim Walz and Lt. Governor Peggy Flanagan. 7 January 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Carley, Kenneth (2001). The Dakota War of 1862. Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87351-392-4. OCLC 46685050.

- ^ McCaslin, Richard B. (15 June 2010). "Great Hanging at Gainesville". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ "DeathPenaltyUSA, the database of executions in the United States". deathpenaltyusa.org. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "The Last Public Execution in America". NPR. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ "On This Day: Kentucky Holds Final Public Execution in the US". findingDulcinea. 14 August 2011. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Blake, Gene (14 October 1982). "Famed warden Duffy of San Quentin dead at 84". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Duffy, Clinton (1962). Eighty-Eight Men and Two Women. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. OCLC 1317754.

- ^ Fimrite, Peter (20 November 2005). "Inside death row. At San Quentin, 647 condemned killers wait to die in the most populous execution antechamber in the United States". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2 July 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ Tengler, U. "Layenspiegel". Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. p.119

- ^ Original German text: Den Juden zwischen zweyen wütenden oder beissenden hunde zu der gewonlichen gerichtstatt zu ziehen. vel schlieffen, mit dem strang oder ketten bey seinen füssen an eynen besondern galgen zwischen die hund nach verkerter mass hencken damit er also von leben zom tod gericht wird

- ^ Cohen, Esther (1993). The Crossroads of Justice: Law and Culture in Late Medieval France. Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Brill. p.92–93

- ^ Archuleta, Roy A. (2006). Where We Come From. Where We Come From, collect. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4243-0472-1. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Müller, Jörg R. (2008). Beziehungsnetze aschkenasischer Juden während des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit [Relationship networks of Ashkenazi Jews during the Middle Ages and Early Modern period] (in German). Hahnsche Buchhandlung. pp. 81, footnote 31. ISBN 978-3-7752-5629-2.

- ^ a b c d Kriegk, G. L. (1868). Deutsches Bürgerthum im Mittelalter. Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Frankfurt am Main, p.243

- ^ Limmer, K. A. (1831). Bibliothek der sächsischen Geschichte. Vol. 2. Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Ronneburg. p.721

- ^ {{lang|de|Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums|nocat=yes}}. Vol. 9 Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Leipzig 1860, p.90

- ^ Henne am Rhyn, O. (1870). {{lang|de|Kulturgeschichte des Zeitalters der neuern Zeit: vom Wiederaufleben der Wissenschaften bis auf die Gegenwart|nocat=yes}}. Vol. 1. Archived 12 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Leipzig: Otto Wigand. p.566

- ^ Battenberg, F. (2002). Von Enoch bis Kafka: Festschrift für Karl E. Grözinger zum 60. Geburtstag. Archived 12 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p.86

- ^ "Öttingen". Jewish Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Haym, R. (1861). Preussische Jahrbücher. Vol. 8. Archived 12 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Berlin: Georg Reimer. p.122–23

- ^ von Heister, Carl (1863). Geschichtliche Untersuchungen über Israel: Die Juden: aufgebürdete Verbrechen. Erlittene Verfolgung. Angethane Schmach. Vol. 3. Naumburg: Tauerschmidt. p. 38. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Neilson, George (1896). Caudatus Anglicus. Edinburgh: George p. Johnston. p. 11, footnote 2.

- ^ Tschamser, P. F. Malachiam (1864) [1724]. Annales oder Jahrs-Geschichten der Saarfüseren oder Minderen Brüdern S. Franc. ord., insgemein Conventualen genannt, zu Thann. Vol. 1. Colmar: K. A. Hoffmann. p. 250. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ The author regards this as probably the last case in which a Jew (although in this case dead) was hanged up by the feet in Germany. Schnitzler, Norbert (2002). "Juden vor Gericht: Soziale Ausgrenzung durch Sanktionen". In Schlosser, Hans; Sprandel, Rolf; Willoweit, Daniel (eds.). Herrschaftliches Strafen seit dem Hochmittelalter: Formen und Entwicklungsstufen (in German). Cologne, Weimar: Böhlau. p. 292. ISBN 978-3-412-08601-5.

- ^ On Kisch's assessment, see for example: Kisch, Guido (1943). Historia Judaica: A Journal of Studies in Jewish History, Especially in Legal and Economic History of the Jews. Vol. 5–6. Historia Judaica. p. 119. On locus in Adam of Bremen's text, see Adam of Bremen (2013). History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen. Translated by Tschan, Francis J.; Reuter, Timothy. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-231-50085-2. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Ryccardi di Sancto Germano Notarii Chronicon Archived 12 March 2004 at the Wayback Machine trans. G. A. Loud

- ^ Bradbury, Jim (2007). The Capetians: Kings of France 987–1328. London: Conitunuum Books. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-8264-3514-9. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Hurton, William (1862). Hearts of Oak, or Naval Yarns. London: Richard Bentley. p. 84.

- ^ "Modern-day 'outlaws' gather to honour Jánošík Archived 16 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine". The Slovak Spectator. 9 July 2012.

- ^ Schober, Gottlob – Deutsche Biographie. 1891. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Müller, Gerhard F. (1762). Sammlung Rußischer Geschichte, 1st and 2nd Part of 7th Volume. St. Petersburg: Kayserl. Academie der Wißenschafften. p. 23. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Stedman, J.G.: "Narrative, of a five years' expedition", Vol.1, London 1813, p.116

- ^ Honour, Hugh (1975). The European Vision of America. Cleveland, Ohio: The Cleveland Museum of Art. p.343

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary (2015 update), OUP, Oxford, UK

- ^ Online "Hang". Compact Oxford English Dictionary of Current English. Archived from the original on 19 October 2004. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ Online "Hang". American Heritage Dictionary. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ "Hang". Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ Jess Stein, ed. (1979). Random House Dictionary of the English Language (1st ed.).

Further reading

[edit]- Jack Shuler, The Thirteenth Turn: A History of the Noose. New York: Public Affairs, 2014, ISBN 978-1-61039-136-8

External links

[edit]- A Case Of Strangulation Fabricated As Hanging

- Obliquity vs. Discontinuity of ligature mark in diagnosis of hanging – a comparative study

- Death Penalty Worldwide Archived 13 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Academic research database on the laws, practice, and statistics of capital punishment for every death penalty country in the world.

Hanging

View on GrokipediaMechanics and Physiology

Mechanism of Death

In hanging, death results from constriction of the neck by a ligature, with the constricting force derived from the gravitational effect of the suspended body's weight, distinguishing it from strangulation, where external manual or non-gravitational force is applied without full body suspension.[7][1][8] In suspension or short-drop hangings, where the body remains partially supported or falls a short distance, the primary mechanism is asphyxia through vascular occlusion rather than airway compression alone. The ligature compresses the carotid arteries and jugular veins, rapidly reducing cerebral blood flow and inducing hypoxia, which manifests in characteristic signs such as the suspended hanging state; protruding tongue due to muscle relaxation and venous congestion; eyes rolled back or half-open and lifeless, with possible bulging and petechiae; head tilted by the ligature; incontinence evidenced by urine and fecal stains; and no response to stimuli. These signs typically appear minutes to hours after death. forensic pathology indicates that pressures as low as 11 pounds on both carotids can cause unconsciousness within 10 seconds, with full body weight in suspension accelerating this to near-immediate cerebral ischemia and neuronal death within 4-5 minutes if uninterrupted.[1][9][10][11] In long-drop hangings, designed for judicial execution, death occurs via biomechanical disruption of the cervical spine. The abrupt deceleration from a calculated drop distance generates forces sufficient to produce a hangman's fracture—a bilateral pars interarticularis fracture of the C2 vertebra—often with anterior dislocation and spinal cord transection, effectively severing neural pathways and causing instantaneous paralysis and cardiorespiratory arrest.[12][13][14] Empirical forensic data from such executions confirm cervical fractures as the dominant lethal pathology when drop parameters align with body weight and rope length to exceed 1,000-2,000 pounds of transient force at the neck.[12][14]Drop Variations and Their Effects

In judicial hangings, the short drop method predominated prior to the mid-19th century, involving suspension from a height of typically 1-2 feet, which relied on gradual asphyxiation through compression of the carotid arteries and trachea rather than immediate cervical disruption.[15] This approach frequently resulted in incomplete or absent neck fractures, prolonging the process of unconsciousness and death to 10-20 minutes or more due to sustained arterial occlusion and venous congestion.[1] The long drop emerged as an engineering refinement in the 19th century, first systematically applied in Ireland around the 1850s and refined in Britain by executioners such as William Marwood, who executed over 100 individuals using calculated falls starting in 1872.[16] Drop lengths were determined via body weight to generate sufficient kinetic energy—targeting approximately 1,260 foot-pounds—for a clean break at the upper cervical vertebrae, typically producing the "hangman's fracture" involving bilateral pedicle fractures of the C2 axis vertebra with anterior displacement relative to C3.[14] Early formulas, such as Samuel Haughton's "standard drop" from 1866, prescribed lengths in feet as 2240 divided by the subject's weight in pounds, yielding drops of 5-9 feet for adults weighing 100-200 pounds, though later revisions by figures like John Berry in the 1880s-1890s adjusted for rope elasticity and submental knot placement to enhance precision.[5] This mechanism aimed to transect the spinal cord, inducing immediate loss of consciousness via neurogenic shock and rapid cardiorespiratory arrest within 15 seconds.[1] Post-1850s implementation of drop tables correlated with autopsy findings indicating higher rates of successful cervical disruption compared to short drops, where fractures occurred in fewer than 10% of cases; long drops achieved vertebral separation or severe trauma in up to 70-80% of examined judicial executions by the late 19th century, though inconsistencies arose from factors like rope slippage, inaccurate weight assessments, or atypical body compositions.[17] Variability persisted, with miscalculations sometimes yielding insufficient force for fracture—resulting in partial strangulation—or excessive energy causing partial decapitation, as evidenced in select British and American cases where post-mortem examinations revealed inconsistent C2-C3 disruptions despite standardized protocols.[18]Potential Complications and Botched Executions

In long-drop hanging executions, excessive force from miscalculated drop distances can result in decapitation, where the head separates from the body due to the rope severing the neck tissues. This occurred in the 1901 execution of Thomas "Black Jack" Ketchum in New Mexico Territory, where officials used a drop length intended for a shorter man, causing his decapitation upon impact.[19] Similarly, in 1930, Arizona executed Eva Dugan by hanging, and the drop led to her decapitation, with her head rolling away from the body, prompting witnesses to vomit from the gruesome scene.[19] Such incidents highlight the precision required in long-drop calculations, factoring in the condemned's weight, neck musculature, and rope strength to achieve cervical fracture without excessive dismemberment.[20] Rope breakage or detachment represents another failure mode, potentially allowing survival or necessitating re-execution. Historical accounts document cases where ropes snapped under strain, as in multiple 19th-century British executions requiring second attempts after breakage.[20] In the United States, equipment malfunctions like loose knots or faulty traps contributed to botches, though specific 1990s rope failures in judicial hangings are scarce given the rarity of the method post-1960s; however, analogous issues persisted in retained jurisdictions.[19] Poor knot placement, often the subaural or submental knot slipping due to improper positioning, or prisoner convulsions altering body dynamics during the drop, frequently prolonged strangulation rather than enabling swift spinal severance.[21] Short-drop hangings, common before standardized long-drop protocols, exhibited higher risks of incomplete lethality, enabling post-execution revivals. In 1724 Scotland, Margaret "Half-Hangit" Dickson was hanged for infanticide but regained consciousness en route to burial, her chest movement alerting the cart driver; she was pardoned and lived another 40 years.[22] Surgeons in 18th- and early 19th-century Britain occasionally attempted resuscitation on freshly hanged bodies for anatomical study, succeeding in cases where cerebral hypoxia had not progressed to irreversible damage, underscoring the method's variability in short drops.[5] Analysis of U.S. executions from 1890 to 2010 indicates a botched rate of 3.1% for hangings, lower than gas chamber (5.4%) but attributable to factors like equipment flaws and procedural errors in transitioning to long-drop systems.[23] Historical records from earlier long-drop adoptions suggest rates approached 5% in unrefined implementations, often from inconsistent drop tables or executioner inexperience.[24]Historical Development

Origins in Ancient Societies