Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Crematorium

View on Wikipedia

A crematorium, crematory or cremation center is a venue for the cremation of the dead. Modern crematoria contain at least one cremator (also known as a crematory, retort or cremation chamber), a purpose-built furnace. In some countries a crematorium can also be a venue for open-air cremation. In many countries, crematoria contain facilities for funeral homes, such as a chapel. Some cemeteries or crematoria also incorporate a columbarium, a place for interring cremation ashes.

History

[edit]

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, cremation could only take place on an outdoor, open pyre; the alternative was burial. In the 19th century, the development of new furnace technology and contact with cultures that practiced cremation led to its reintroduction in the Western world.[1]

The organized movement to instate cremation as a viable method for body disposal began in the 1870s. In 1869 the idea was presented to the Medical International Congress of Florence by Professors Coletti and Castiglioni "in the name of public health and civilization". In 1873, Professor Paolo Gorini of Lodi and Professor Lodovico Brunetti of Padua published reports or practical work they had conducted.[2][3] A model of Brunetti's cremating apparatus, together with the resulting ashes, was exhibited at the Vienna Exposition in 1873 and attracted great attention, including that of Sir Henry Thompson, a surgeon and Physician to the Queen Victoria, who "returned home to become the first and chief promoter of cremation in England".[4]

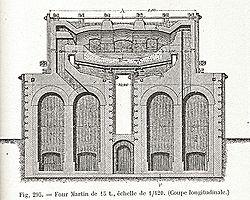

Meanwhile, Sir Charles William Siemens had developed his regenerative furnace in the 1850s. His furnace operated at a high temperature by using regenerative preheating of fuel and air for combustion. In regenerative preheating, the exhaust gases from the furnace are pumped into a chamber containing bricks, where heat is transferred from the gases to the bricks. The flow of the furnace is then reversed so that fuel and air pass through the chamber and are heated by the bricks. Through this method, an open-hearth furnace can reach temperatures high enough to melt steel, and this process made cremation an efficient and practical proposal. Charles's nephew, Carl Friedrich von Siemens perfected the use of this furnace for the incineration of organic material at his factory in Dresden. The radical politician, Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke, took the corpse of his dead wife there to be cremated in 1874.[clarify] The efficient and cheap process brought about the quick and complete incineration of the body and was a fundamental technical breakthrough that made industrial cremation a practical possibility.[5]

The first crematorium in the West opened in Milan in 1876.[6][7] By the end of the 19th century, several countries had seen their first crematorium open. Golders Green Crematorium was built from 1901 to 1928 in London and pioneered two features that would become common in future crematoria: the separation of entrance and exit, and a garden of remembrance.[1]

| Country | Location of first crematorium | Year opened | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crematorium Temple, Monumental Cemetery, Milan | 1876 | [6][7] | |

| LeMoyne Crematory, Washington County, Pennsylvania | 1876 | [8][9] | |

| Gotha | 1878 | [7] | |

| Woking Crematorium, Woking, Surrey | 1885 | [10] | |

| Cementerio de la Almudena, Madrid | 1973 | [11] | |

| Stockholm | 1887 | [7] | |

| Zürich | 1889 | [7] | |

| Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris | 1889 | [7] | |

| Church of St. Nicholas, Gdańsk | 1914 | [7] | |

| Pardubice Crematorium | 1923 | [12] | |

| Uccle Crematorium, Uccle, Brussels | 1933 | [13] |

Crematoria in Nazi Death Camps

[edit]In the extermination camps created by the authorities of Nazi Germany during World War II with the "final solutions to the Jewish question", crematoria were widely used for the disposal of corpses.[14][15] The most technically advanced cremation ovens were those developed by Topf and Sons from Erfurt.[citation needed]

Ceremonial facilities

[edit]

While a crematorium can be any place containing a cremator, modern crematoria are designed to serve a number of purposes. As well as being a place for the practical but dignified disposal of dead bodies, they must also serve the emotional and spiritual needs of the mourners.[1]

The design of a crematorium is often heavily influenced by the funeral customs of its country. For example, crematoria in the United Kingdom are designed with a separation between the funeral and cremation facilities, as it is not customary for mourners to witness the coffin being placed in the cremator. To provide a substitute for the traditional ritual of seeing the coffin descend into a grave, they incorporate a mechanism for removing the coffin from sight. On the other hand, in Japan, mourners will watch the coffin enter the cremator, then will return after the cremation for the custom of picking the bones from the ashes.[1]

Cremators

[edit]While open outdoor pyres were used in the past and are often still used in many areas of the world today, notably India, most cremation in industrialized nations takes place within enclosed furnaces designed to maximize use of the thermal energy consumed while minimizing the emission of smoke and odors.

Thermodynamics

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

A human body usually contains a negative caloric value, meaning that energy is required to combust it. This is a result of the high water content; all water must be vaporized which requires a very large amount of thermal energy.

A 68 kg (150 lbs) body which contains 65% water will require 100 MJ of thermal energy before any combustion will take place. 100 MJ is approximately equivalent to 3 m3 (105 ft3) of natural gas, or 3 liters of fuel oil (0.8 US gallons). Additional energy is necessary to make up for the heat capacity ("preheating") of the furnace, fuel burned for emissions control, and heat losses through the insulation and in the flue gases.

As a result, crematories are most often heated by burners fueled by natural gas. LPG (propane/butane) or fuel oil may be used where natural gas is not available. These burners can range in power from 150 to 400 kilowatts (0.51 to 1.4 million British thermal units per hour).

Crematories heated by electricity also exist in India, where electric heating elements bring about cremation without the direct application of flame to the body.

Coal, coke, and wood were used in the past, heating the chambers from below (like a cooking pot). This resulted in an indirect heat and prevented mixing of ash from the fuel with ash from the body. The term "retort" when applied to cremation furnaces originally referred to this design.

There has been interest, mainly in developing nations, to develop a cremator heated by concentrated solar energy.[16] Another design starting to find use in India, where wood is traditionally used for cremation, is a cremator based around a wood gas fired process. Due to the manner in which the wood gas is produced, such crematories use only a fraction of the required wood; and according to multiple sources, have far less impact on the environment than traditional natural gas or fuel oil processes.[17]

Combustion system

[edit]A typical unit contains a primary and secondary combustion chamber. These chambers are lined with a refractory brick designed to withstand the high temperatures.

The primary chamber contains the body – one at a time usually contained in some type of combustible casket or container. This chamber has at least one burner to provide the heat which vaporizes the water content of the body and aids in combustion of the organic portion. A large door exists to load the body container. Temperature in the primary chamber is typically between 760–980 °C (1,400–1,800 °F).[18] Higher temperatures speed cremation but consume more energy, generate more nitric oxide, and accelerate spalling of the furnace's refractory lining.

The secondary chamber may be at the rear or above the primary chamber. A secondary burner(s) fires into this chamber, oxidizing any organic material which passes from the primary chamber. This acts as a method of pollution control to eliminate the emission of odors and smoke. The secondary chamber typically operates at a temperature greater than 900 °C (1,650 °F).

Air pollution control and energy recovery

[edit]The flue gases from the secondary chamber are usually vented to the atmosphere through a refractory-lined flue. They are at a very high temperature, and interest in recovering this thermal energy e.g. for space heating of the funeral chapel, or other facilities or for distribution into local district heating networks has arisen in recent years. Such heat recovery efforts have been viewed in both a positive and negative light by the public. 760–980 °C (1,400–1,800 °F).[19]

In addition, filtration systems (baghouses) are being applied to crematories in many countries. Activated carbon adsorption is being considered for mercury abatement (as a result of dental amalgam). Much of this technology is borrowed from the waste incineration industry on a scaled-down basis. With the rise in the use of cremation in Western nations where amalgam has been used liberally in dental restorations, mercury has been a growing concern. 900 °C (1,650 °F)

Automation

[edit]The application of computer control has allowed cremators to be more automated, in that temperature and oxygen sensors within the unit along with pre-programmed algorithms based upon the weight of the deceased allow the unit to operate with less user intervention. Such computer systems may also streamline recordkeeping requirements for tracking, environmental, and maintenance purposes.

Additional aspects

[edit]The time to carry out a cremation can vary from 70 minutes to 210 minutes. Cremators used to run on timers (some still do) and one would have to determine the weight of the body and calculate for how long the body has to be cremated. Other types of crematories merely have a start and a stop function for the cremation displayed on the user interface. The end of the cremation must be judged by the operator who in turn stops the cremation process.[20][21] As an energy-saving measure, some cremators provide heating for the building.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Typology: Crematorium". Architectural Review. 14 November 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Cobb, John Storer (1901). A Quartercentury of Cremation in North America. Knight and Millet. p. 150.

- ^ "Brunetti, Lodovico" by Giovanni Cagnetto, Enciclopedia Italiana (1930)

- ^ "Introduction". Internet. The Cremation Society of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ Alon Confino; Paul Betts; Dirk Schumann (2013). Between Mass Death And Individual Loss: The Place of the Dead in Twentieth-Century Germany. Berghahn Books. p. 94. ISBN 9780857453846.

- ^ a b Boi, Annalisa; Celsi, Valeria (2015). "The Crematorium Temple in the Monumental Cemetery in Milan". In_Bo. Ricerche e Progetti per Il Territorio. 6 (8). doi:10.6092/issn.2036-1602/6076.

- ^ a b c d e f g Encyclopedia of Cremation by Lewis H. Mates (p. 21-23)

- ^ "The LeMoyne Crematory". Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ "An Unceremonious Rite; Cremation of Mrs. Ben Pitman" (PDF). The New York Times. 16 February 1879. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ The History Channel. "26 March – This day in history". Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

- ^ Revista funeraria (7 November 2018). "Evolución de los servicios funerarios en el último siglo en España". Archived from the original on 13 January 2024.

- ^ Bixquert Vicente, Irene (23 January 2019). "Construcción de crematorios en la República Checa en el siglo XX: Análisis contextual y estudio de un caso".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Achter de coulissen van het crematorium: 'Uitvaart wordt steeds meer een vertoning'". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ "Crematorium at the Natzweiler-Struthof camp (Alsace, France)". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ "Ovens at Dachau camp". Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ "Development of a Solar Crematorium" (PDF).

- ^ "Gasifier Based Crematorium, Wood Gasifier Based Crematorium, Biomass Gasifier Crematorium Exporters". gasifiers.co.in. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ "How Is A Body Cremated?". Cremation Resource. US. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Nobel, Justin (24 May 2011). "New Life for Crematories' Waste Heat". Miller-McCune. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ Cremationprocess.co.uk Archived 25 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ashes to Ashes: The Cremation Process Explained". everlifememorials.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

External links

[edit] Media related to Crematoria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Crematoria at Wikimedia Commons

Crematorium

View on GrokipediaHistory

Ancient Origins and Cultural Practices

The earliest archaeological evidence of cremation dates to the Paleolithic period, with partially cremated human remains discovered at Lake Mungo in Australia, radiocarbon-dated to approximately 40,000 years before present.[6] Additional early instances appear in the Neolithic Near East, including a skull fragment from the site of Beisamoun in Israel, intentionally cremated at temperatures exceeding 500°C and dated to between 7013 and 6700 BCE, representing the oldest confirmed cremation in that region.[7][8] These findings indicate cremation emerged independently across distant populations, likely as a practical response to environmental constraints or ritualistic intent to transform remains, though interpretations vary due to fragmentary evidence and dating challenges. In ancient India, cremation became a central funerary practice during the Vedic period (c. 1500–500 BCE), rooted in texts like the Rigveda that prescribe open-air pyres fueled by wood to release the soul from the body and return physical elements to nature—earth, water, fire, air, and ether.[9] This rite symbolized spiritual purification and continuity with cosmic cycles, with the eldest son typically lighting the fire (agni) while mantras invoked deities; ashes and bone fragments were ritually immersed in sacred rivers like the Ganges to facilitate reincarnation or moksha (liberation).[10] Practices trace back further to the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3300–1300 BCE), where cremated remains in urns suggest early adoption, contrasting with contemporaneous burial norms elsewhere in the region.[9] Among Indo-European cultures of the Mediterranean, cremation gained prominence in ancient Greece around 1000 BCE during the Archaic period, often involving public pyres at which mourners offered libations and sacrificed animals to honor the deceased and expedite the soul's journey to Hades.[11] Ashes were collected in urns for burial or sea dispersal, as depicted in Homeric epics like the Iliad, where heroes such as Patroclus received elaborate cremations emphasizing martial valor and communal remembrance.[12] In Rome, from the mid-Republic (c. 500 BCE) onward, cremation supplanted inhumation as the dominant method among elites, involving a procession (pompa), public eulogy, and pyre ignited by family amid incense and effigies; this reflected beliefs in fire's purifying power and the impermanence of flesh, with urns interred in columbaria.[13][11] By the early Empire, such rites underscored social status, though regional variations persisted, and cremation's favor waned with the rise of Christian burial preferences in the 3rd–4th centuries CE.[11]Decline and Revival in the Modern Era

The practice of cremation declined sharply in Europe with the expansion of Christianity from the early centuries AD. Christians favored inhumation to honor the body's anticipated resurrection, viewing cremation as incompatible with doctrines emphasizing corporeal integrity, as articulated by early theologians such as Tertullian and Augustine.[14] By the 4th century, following Christianity's legalization under the Edict of Milan in 313 AD and its elevation to state religion in 380 AD, burial had supplanted cremation as the dominant funerary rite across the Roman Empire and subsequent medieval societies, with cremation relegated to exceptional circumstances like epidemics or wartime necessities.[15] This shift persisted for over a millennium, reinforced by ecclesiastical prohibitions and cultural norms prioritizing churchyard interment.[16] Cremation's modern revival emerged in the 19th century amid rapid urbanization, recurrent cholera outbreaks, and apprehensions regarding overcrowded cemeteries contaminating water supplies. Proponents, including medical professionals, championed cremation for its sanitary benefits and efficient land use, countering the inefficiencies of traditional burial. In 1874, British surgeon Sir Henry Thompson founded the Cremation Society of England to advocate for legal recognition and technological development of crematoria, drawing on earlier experimental designs like those demonstrated by Italian engineer Giovanni Polidoro.[4] The society's efforts culminated in the construction of Europe's first permanent crematoria in 1878 at Woking, England, and Gotha, Germany, though religious and legal opposition—rooted in fears of hasty disposal concealing crimes—postponed the inaugural lawful cremation in Britain until 1885 at Woking.[4] By the early 20th century, cremation had established footholds in Protestant-majority nations, where secular rationalism eroded doctrinal resistance more readily than in Catholic regions. Adoption accelerated post-World War II with declining religiosity, rising costs of burial plots, and environmental considerations favoring reduced land consumption. In urban centers of England, Scotland, Germany, and Italy, cremation rates transitioned from negligible levels before 1900 to double digits by the 1930s, reflecting a broader funerary secularization.[17] This trend continues, with contemporary rates exceeding 70% in the United Kingdom and Sweden, underscoring cremation's integration into mainstream practices despite initial ecclesiastical condemnation.[18]Industrial-Scale Applications in the 20th Century

The most prominent example of industrial-scale crematoria in the 20th century occurred during World War II in Nazi German concentration and extermination camps, where engineering firms adapted furnace technology for the mass incineration of human remains as part of the regime's extermination policies. The company J.A. Topf & Sons, a German engineering firm originally specializing in heating systems, designed and supplied multi-muffle cremation ovens capable of processing multiple bodies simultaneously to camps including Auschwitz-Birkenau, Buchenwald, and Dachau.[19] These installations marked a shift from traditional single-body cremation to high-throughput systems, with ovens featuring continuous operation muffles to handle volumes far exceeding civilian funeral capacities.[20] At Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest such facility, four main crematoria (II through V) were constructed between 1942 and 1943, equipped with Topf & Sons ovens totaling 46 muffles across the complex. Crematoria II and III each contained five triple-muffle ovens, with a nominal design capacity of 1,440 corpses per day per unit, while Crematoria IV and V had eight-muffle ovens rated for 768 and 1,440 daily, respectively; in practice, operations exceeded these figures through overloading and reduced cremation times.[21] Engineers like Kurt Prüfer of Topf & Sons optimized the systems for efficiency, incorporating features such as oil-fired heating and ventilation to minimize fuel use and accelerate incineration to as little as 20-30 minutes per body under forced conditions, though standard civilian cremations required 60-90 minutes.[22] The total daily capacity across Birkenau's crematoria was estimated by camp personnel at 4,400 to 5,000 bodies, supplemented by open-air pits during peak operations in 1944.[23] This engineering was driven by logistical demands of the Holocaust, where crematoria disposed of victims gassed in adjacent chambers, with Topf & Sons delivering over 25 ovens to Auschwitz alone and patenting designs for even larger continuous-action furnaces capable of 3,000-7,000 bodies per day, though not all were built.[24] Post-liberation analyses, including SS documents and survivor testimonies, confirm the facilities' role in incinerating over one million victims at Auschwitz, highlighting adaptations like body-fat utilization for fuel efficiency to sustain 24-hour operations.[21] Outside the Nazi context, no comparable purpose-built industrial crematoria emerged in the 20th century; wartime mass cremations elsewhere, such as in Japanese-occupied territories or post-battle disposals, typically relied on open pyres rather than enclosed, engineered facilities.[19]Facilities and Design

Architectural and Ceremonial Elements

Crematorium architecture prioritizes serene and respectful environments, often incorporating natural materials, subdued color palettes, and forms that integrate with landscapes to evoke tranquility amid grief.[25][26] Designs draw from historical precedents like burial mounds or classical motifs while emphasizing functionality and emotional resonance, avoiding ostentatious elements in favor of minimalist or organic shapes that symbolize transition and peace.[26][27] Modern examples feature curvaceous structures or funnel-like forms that guide mourners through spatial sequences, culminating near cremation areas without overt visibility of industrial components.[28][27] Ceremonial elements center on dedicated spaces for memorial services, including chapels or assembly halls configured for religious, secular, or personalized rituals, typically resembling modest ecclesiastical interiors or neutral venues with flexible seating for 50-150 attendees.[29][30] These areas often include antechambers for private farewells and viewing windows or partitions allowing optional witnessing of the committal process, enhancing closure while respecting privacy preferences.[30][31] Adjacent waiting lounges and circulation paths facilitate dignified processions, with acoustic treatments and lighting designed to support solemn atmospheres without imposing specific ideologies.[25] Landscaped grounds form integral ceremonial extensions, featuring remembrance gardens with benches, water elements, and urn columbaria that enable ongoing commemoration through scattering, placement, or inscribed memorials, blending built and natural realms to sustain familial connections post-cremation.[32][33] Such designs adhere to site-specific planning principles, ensuring accessibility via public transport and seclusion from residential zones to minimize disruption while maximizing contemplative utility.Operational Infrastructure

The core of a crematorium's operational infrastructure consists of one or more cremation retorts, specialized furnaces designed to withstand sustained high temperatures while containing the combustion process. These chambers are typically constructed with refractory brick linings capable of enduring temperatures exceeding 1,600°F (871°C) in the primary combustion zone and up to 2,200°F (1,205°C) in associated stacks or secondary chambers for complete afterburning of emissions.[34] [35] Modern retorts feature dual-casing designs with air-cooling to manage external skin temperatures, ensuring operator safety and structural integrity during cycles that last 70 to 90 minutes for an average adult body.[34] [36] Loading systems facilitate the introduction of combustible containers into the retort, often via hydraulic trays or rails that slide the remains into the chamber horizontally, minimizing manual handling and exposure to heat. Combustion is initiated using natural gas or propane burners, with airflow regulated to achieve efficient oxidation; capacities range from 1,000 pounds per unit, processing up to 250 pounds per hour depending on the model.[37] [36] Control interfaces, such as touch-screen PLC systems, monitor parameters like temperature, draft, and cycle timing to ensure consistent results and compliance with operational standards.[38] Post-cremation, infrastructure includes cooled ash collection trays or hoppers that capture remaining bone fragments, which are then transferred to a separate processing area for mechanical pulverization into fine powder using specialized grinders. Ventilation infrastructure encompasses induced draft fans and ducting to maintain negative pressure within the retort, directing exhaust gases through secondary chambers or abatement systems before release.[39] Electrical and fuel supply systems support continuous operation, with backup generators often integrated for reliability in multi-retort facilities handling daily volumes of several cremations.[38] These elements collectively enable throughput rates aligned with demand, such as 5 to 10 units per retort per day in high-volume settings.[36]Cremation Technology

Fundamental Processes and Thermodynamics

The cremation process in a modern retort involves the controlled application of high heat to induce dehydration, pyrolysis, and oxidation of the human body, reducing organic tissues to ash and bone fragments while mineralizing inorganic components. The primary chamber, preheated to 760–982°C (1400–1800°F), facilitates these stages through convective, radiative, and conductive heat transfer from combustion gases, typically generated by natural gas burners.[40] The human body, averaging 60–70% water by mass in adults, first undergoes dehydration, where free and bound water evaporates, requiring significant latent heat input estimated at approximately 100 MJ for a 68 kg (150 lb) body containing 65% water before substantive combustion occurs.[41] This endothermic phase transitions to pyrolysis around 200–500°C, where thermal decomposition breaks down proteins, fats, and carbohydrates into volatile gases, tars, and char without oxygen, governed by Arrhenius kinetics and bond dissociation energies.[42] Subsequent oxidation of released volatiles and char combustion above 500–800°C provide exothermic contributions via reactions such as C + O₂ → CO₂ (ΔH = -394 kJ/mol) and similar hydrocarbon oxidations, partially self-sustaining the process after ignition but requiring continuous external fuel to maintain temperature against heat losses.[43] Overall energy balance in the retort accounts for sensible heating of solids and gases, latent heats, reaction enthalpies, and losses through exhaust (up to 70–80% inefficiency in older systems), with total thermal input per cremation averaging 2.38 million BTU (approximately 2.51 GJ or 2510 MJ) for an average adult, primarily from natural gas consumption of 20–40 therms.[44] Heat transfer modeling via computational fluid dynamics reveals turbulence-enhanced convection dominates early stages, while radiation prevails in later char burnout, with chamber geometry influencing uniformity and duration (typically 1.5–3 hours).[45] Thermodynamic efficiency is limited by the open-system design, where exhaust gases at 800–1000°C carry away enthalpy, though secondary chambers oxidize unburnt species (e.g., CO to CO₂) for completeness.[46] Bone mineralization occurs last, with hydroxyapatite (Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂) dehydrating and recrystallizing above 600°C, yielding calcined fragments that withstand peak temperatures without full fusion. Empirical studies confirm that incomplete oxidation risks residual organics if airflow or residence time is insufficient, underscoring the causal role of oxygen stoichiometry and temperature gradients in process reliability.[47]Combustion Systems and Equipment

Modern crematorium combustion systems center on specialized furnaces called cremators or retorts, designed to achieve high-temperature incineration of human remains through controlled combustion. These systems typically operate at temperatures ranging from 1,400°F to 2,000°F (760°C to 1,093°C) to reduce organic material to bone fragments while minimizing environmental emissions.[48][49] The primary chamber, or retort, houses the body in a refractory-lined enclosure that withstands extreme heat, with burners providing the initial ignition and sustained flame.[50] Gas-fired models, predominant in the industry, use natural gas or propane as fuel, with direct spark ignition systems eliminating the need for pilots to enhance safety and efficiency.[35] Key equipment includes multi-chamber designs featuring a primary combustion zone and a secondary afterburner chamber, where temperatures are maintained to ensure complete oxidation of volatiles and particulates.[51] Burners, often rated up to 270 kW, deliver precise fuel-air mixtures via automated controls, such as microprocessor-based systems with digital temperature readouts and recorders for regulatory compliance.[52] Refractory materials line the chambers to retain heat, with "hot hearth" configurations in high-volume models promoting fuel efficiency by preheating incoming air and reducing cycle times to 70-90 minutes per cremation.[53] Blower systems regulate airflow for optimal combustion, preventing incomplete burning and supporting 24-hour operations in air-controlled setups.[54] Electric cremators represent an emerging alternative, relying on resistive heating elements powered by electricity rather than fossil fuels, potentially lowering carbon emissions but requiring higher infrastructure costs and longer preheat times.[55] Hybrid systems combining gas and electric components are under development by European manufacturers to balance efficiency and emissions.[56] Fuel efficiency in gas systems has improved, with modern retorts consuming 30-35% less natural gas through insulated designs and sequential warm-start operations that retain residual heat between cycles.[57] Stainless steel trims and Siemens-based control platforms, like the Trilogy system, enable precise monitoring and automation, reducing operator intervention while ensuring consistent performance.[58][59]Pollution Control, Energy Recovery, and Sustainability

Modern cremators employ multi-stage pollution abatement systems to minimize emissions of particulate matter, nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur oxides (SOx), mercury, and persistent organic pollutants. Primary combustion occurs in the main chamber at temperatures around 800–1000°C, followed by secondary combustion in an afterburner at 850–1100°C to ensure complete oxidation of volatile organics and reduce dioxins. [60] Additional controls include fabric filters or baghouses for capturing particulates, activated carbon injection for adsorbing mercury and dioxins, and selective catalytic reduction (SCR) or non-catalytic reduction (SNCR) for NOx abatement. [61] Wet scrubbers may neutralize acid gases like HCl and SOx. These technologies, when properly maintained, achieve emission levels compliant with strict regulations, such as those in the European Union or Netherlands, where mercury emissions are nearly eliminated through carbon adsorption and filtration. [62] Energy recovery systems in crematoria capture waste heat from flue gases, which exit at 200–400°C, using heat exchangers to produce hot water or steam for facility heating, district heating networks, or even electricity generation via organic Rankine cycles. [63] For instance, indirect heat recovery via gas-to-water exchangers can offset up to 20–30% of operational energy needs in larger facilities, reducing overall fuel consumption. [64] In the UK and Netherlands, recovered heat has been integrated into district heating, displacing natural gas during peak demand, though scalability is limited by the intermittent nature of cremation cycles. [63] [65] Sustainability efforts focus on mitigating cremation's carbon footprint, estimated at 242–250 kg of CO2 equivalent per body from natural gas combustion, excluding body mass contributions. [66] [67] While direct greenhouse gas emissions exceed those of burial, which avoids combustion but incurs land use and embalming chemical impacts, modern controls and energy recovery lower net environmental burdens compared to unregulated older systems. [68] Transition to electric or biofuel cremators is emerging to further reduce fossil fuel dependence, though high electricity grid emissions in coal-reliant regions may offset gains. [69] Empirical assessments indicate crematoria contribute negligibly to local air quality issues when equipped with abatement, representing less than 1% of urban PM2.5 or NOx inventories in most cases.Automation and Technological Advancements

Modern cremation systems incorporate programmable logic controllers (PLCs) and sensors to automate the regulation of temperature, airflow, and combustion phases, ensuring consistent outcomes and minimizing operator intervention.[54] These controls maintain chamber temperatures between 760°C and 1,150°C, with automated cycles that include pre-heating, primary combustion, secondary burning of residues, and controlled cooling to prevent structural damage to remains.[70] Software algorithms adjust oxygen levels and fuel input in real-time based on sensor feedback, reducing fuel consumption by up to 20% compared to manual operations and ensuring complete reduction of organic material to bone fragments within 1.5 to 3 hours per cycle.[71] Advancements in user interfaces have integrated touchscreen panels and remote diagnostic tools, allowing operators to monitor multiple retorts simultaneously from a central station, with one technician capable of overseeing four units efficiently.[72] Automatic doors and loading mechanisms further enhance safety and energy retention by minimizing heat loss during insertion and ash retrieval, while predictive maintenance software detects anomalies like refractory wear to avert downtime.[73] Systems from manufacturers such as DFW Europe employ proprietary software that logs process data for regulatory audits, ensuring traceability and compliance with emission standards.[71] Emerging integrations of artificial intelligence aim to optimize energy use and predict equipment failures through machine learning analysis of historical data, potentially reducing human error in parameter settings.[74] Automated guided vehicles (AGVs) for remains transport within facilities streamline workflows, enabling coordinated movement via remote scheduling to handle high volumes without manual handling risks.[75] These technologies have lowered operational costs and improved throughput, with facilities reporting up to 30% gains in daily capacity since the widespread adoption of PLC-based automation in the early 2000s.[76]Legal, Regulatory, and Economic Dimensions

Licensing, Standards, and Global Variations

Licensing for crematorium operations generally requires approval from governmental bodies to ensure public health, safety, and environmental compliance, with requirements encompassing facility construction, equipment certification, and personnel qualifications. In the United States, oversight occurs at the state level, where establishments must secure specific crematory licenses tied to a fixed location and often mandate operator training from recognized bodies such as the Cremation Association of North America (CANA), including exams and proof of equipment manufacturer courses renewed every five years in jurisdictions like Maryland.[77][78] State laws may also necessitate affiliation with licensed funeral directors and adherence to public health refrigeration standards for unembalmed remains.[79][80] Operational standards emphasize rigorous protocols for remains handling, combustion efficiency, and emissions mitigation to minimize public health risks and ecological impact. The Cremation Association of North America outlines procedures requiring secure identification, refrigeration below 36°F (2°C) for non-embalmed bodies unless local health codes differ, and post-cremation pulverization of residues to uniform particle size.[80] Internationally, facilities must meet furnace temperatures exceeding 1400°F (760°C) for complete combustion and incorporate filters for pollutants like mercury, as recommended under frameworks addressing persistent organic pollutants.[81] Voluntary industry codes, such as those from the International Cemetery, Cremation and Funeral Association (ICCFA), promote ethical practices including accurate ash return and facility inspections, though enforcement relies on national regulators.[82] Global variations reflect jurisdictional priorities, with decentralized systems in federal nations contrasting uniform national mandates elsewhere. In the United Kingdom, the Cremation (England and Wales) Regulations 2008, administered via local authorities, require medical referee approval through standardized forms (e.g., Cremation 1 for applications), mandatory inspections, and maintenance of clean, orderly premises under the 1902 Cremation Act's distance rules from dwellings.[83][84][85] European countries diverge: the Netherlands mandates environmental permits with afterburner chambers, mercury abatement, and prohibitions on certain coffin materials like lead-lined ones to curb emissions.[86] In Germany, cremations occur exclusively in licensed installations enforcing hygiene and emissions protocols, while Norway imposes secular, state-overseen processes with tight controls on ash disposition.[87][88] These differences arise from varying emphases on land scarcity, pollution limits, and cultural norms, leading to practices like grave reuse in space-constrained regions versus expansive burial preferences elsewhere.[89]Environmental Regulations and Compliance

Crematoriums are regulated under air quality frameworks to control emissions of pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon monoxide (CO), sulfur dioxide (SO2), particulate matter (PM), and mercury (Hg), primarily from combustion and dental amalgam incineration. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) classifies most crematories as minor sources under the Clean Air Act, with annual emissions typically below 5 tons for criteria pollutants, far less than major sources exceeding 100-250 tons. The EPA utilizes AP-42 emission factors for estimating outputs like PM and criteria gases, derived from tests such as those at the Bronx Crematorium in 1998, but has not imposed specific federal mercury limits due to measured levels ranging from 0.008 to 2.30 mg per cremation, deemed insufficient for regulation. [90] [91] [92] In the European Union, crematorium emissions fall under broader industrial emissions directives, with the revised Mercury Regulation effective July 30, 2024, prohibiting intentional mercury uses but lacking specific crematoria emission limit values (ELVs), prompting calls from environmental groups for EU-level controls based on 2020 findings indicating variable Hg outputs. [93] [94] National variations exist; for instance, OSPAR guidelines recommend upstream particulate removal via fabric filters achieving 99.9% mercury reduction, targeting flue gas concentrations of 0.005-0.013 mg/m³. [95] The EMEP/EEA guidebook identifies key emissions including PM, Hg, and non-methane volatile organic compounds, advising best available techniques like wet scrubbers for acid gases and dioxins. [96] Compliance involves continuous or periodic monitoring using systems like continuous emissions monitoring systems (CEMS) for NOx, SOx, and CO, alongside pollution control equipment such as afterburners, fabric filters, and scrubbers to meet local standards. [97] In the United Kingdom, Process Guidance Note 5/2(12) mandates emission limit values, operator notifications for monitoring, and equivalent methods approved by regulators, with larger facilities required to minimize SO2, HCl, and CO via abatement. Globally, the Stockholm Convention's toolkit promotes air pollution controls for new crematoria, including equipment for particulates and metals, though no uniform international standards exist, leading to disparate practices like setback distances and Hg monitoring in select countries. [81] Studies from 2020 confirm crematoria emissions of PCDD/Fs, Hg, and PM2.5 remain low relative to other sources, supporting targeted rather than blanket regulations.Economic Factors and Industry Statistics

The global funeral and cremation services market, which includes crematorium operations, was valued at USD 62.72 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach USD 87.00 billion by 2030, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.82%.[98] This expansion reflects rising cremation adoption due to lower costs compared to traditional burials, which can exceed USD 7,000 including casket, vault, and plot, while direct cremations range from USD 2,000 to USD 7,200.[99] [100] Cremation-specific segments, such as furnaces, were valued at USD 593.69 million in 2024, expected to grow to USD 867.20 million by 2033, driven by technological upgrades for efficiency and emissions control.[101] In the United States, crematories generated USD 4.274 billion in revenue in recent years, part of a broader funeral industry totaling over USD 20 billion, with cremation rates projected at 63.4% in 2025—up from 61.9% in 2024—potentially surpassing burials by a six-to-one ratio by 2045.[102] [103] This shift economically pressures cemeteries, which face declining demand for plots, while boosting crematorium revenues through basic services priced at USD 800–1,500 per case and add-ons like urns or memorialization.[104] [105] Startup costs for a new crematorium range from USD 1.5 million to USD 3 million, covering equipment, facilities, and compliance, with ongoing operations including fuel (natural gas or propane) and maintenance yielding net profits around USD 20,000 annually per unit after expenses in mid-sized facilities.[106] [107] Key economic factors include energy efficiency gains from modern retorts, which reduce fuel costs by up to 20% via heat recovery systems, and preneed sales that stabilize revenue amid fluctuating death rates.[108] Regulatory compliance, such as emissions standards, adds operational costs but incentivizes sustainable tech adoption, contributing to moderated growth rates as cremation penetration peaks in mature markets like North America and Europe.[109] Overall, cremation's lower resource demands—minimal land use versus burial plots—enhance long-term industry viability, though competition from alternatives like alkaline hydrolysis could fragment market share if scaled.[110][111]Cultural Reception and Debates

Adoption Trends and Comparisons to Alternatives

Cremation rates have risen globally since the late 19th century, accelerating in the 20th and 21st centuries due to urbanization, rising cemetery costs, and declining religious prohibitions against body destruction. In 2024, the worldwide average cremation rate reached approximately 61.9% of dispositions, up from negligible levels in most Western countries a century prior.[112] This shift reflects practical necessities in densely populated regions and economic pressures, rather than uniform cultural endorsement. Historical data show U.S. rates climbing from under 4% in 1960 to 61.8% in 2024, with projections to 67.9% by 2029, while Canada's rate advanced from 73.7% in 2020 to 76.7% in 2024.[113] Growth has decelerated in mature markets exceeding 75%, as saturation limits further expansion.[114] Adoption varies sharply by region, driven by land availability, population density, and religious demographics. Japan maintains the highest rate at 99.97%, compelled by acute land scarcity and longstanding cultural norms favoring ash interment in family urns.[115] Nordic countries like Sweden exhibit rates above 80%, supported by secular societies and efficient public infrastructure, whereas Catholic-majority nations such as Italy and Ireland lag below 20%, reflecting doctrinal preferences for intact burial.[116] In Asia, rates exceed 70% in India and approach 92% in South Korea, tied to Hindu traditions and urban constraints.[117] The table below summarizes 2023-2024 rates for select countries:| Country | Cremation Rate (%) | Primary Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Japan | 99.97 | Land scarcity, cultural practice |

| Sweden | ~82 | Secularism, space efficiency |

| United Kingdom | ~80 | Cost, urbanization |

| Canada | 76.7 | Economic factors, mobility |

| United States | 61.8 | Rising costs of burial plots |

| Italy | <20 | Religious opposition to cremation |

.jpg/250px-Maitland_Crematorium,_Cape_Town_(South_Africa).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Maitland_Crematorium,_Cape_Town_(South_Africa).jpg)