Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

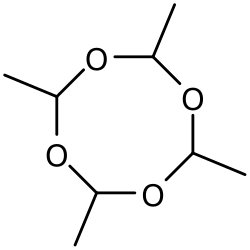

Metaldehyde

View on Wikipedia | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2,4,6,8-tetramethyl-

| |

| Other names

metaldehyde

metacetaldehyde ethanal tetramer | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.274 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1332 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C8H16O4 | |

| Molar mass | 176.212 g/mol |

| Density | 1.27 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 246 °C (475 °F; 519 K) |

| Boiling point | sublimes at 110 to 120 °C (230 to 248 °F; 383 to 393 K) |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling:[1] | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H228, H301, H361f, H412 | |

| P203, P210, P240, P241, P264, P270, P273, P280, P301+P316, P318, P321, P330, P370+P378, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Metaldehyde is an organic compound with the formula (C8H16O4). It is used as a pesticide against slugs and snails.[2] It is the cyclic tetramer of acetaldehyde.[3]

Production and properties

[edit]Metaldehyde is flammable, toxic if ingested in large quantities, and irritating to the skin and eyes. It has a white crystalline appearance with a menthol odor.[4]

Metaldehyde is obtained in moderate yields by treatment of acetaldehyde with chilled mineral acids. The liquid trimer, paraldehyde is also obtained. The reaction is reversible; upon heating to about 80 °C, metaldehyde and paraldehyde revert to acetaldehyde.

Metaldehyde exists as a mixture of four stereoisomers, molecules that differ with respect to the relative orientation of the methyl groups on the 8-membered ring. The stereoisomers have respectively the molecular symmetries Cs (with symmetry of order 2), C2v (order 4), D2d (order 8), and C4v (order 8). All have at least one plane of reflexion, so none of them is chiral.

Uses

[edit]As a pesticide

[edit]

It is sold under various trade names as a molluscicide, including Antimilice, Ariotox, Blitzem (in Australia), Cekumeta, Deadline, Defender (in Australia), Halizan, Limacide, Limatox, Limeol, Meta, Metason, Mifaslug, Namekil, Slug Fest, and Slugit. Typically it is applied in pellet form, but it is also found as a liquid spray, granules, paste, or dust. Often the pesticide includes bran or molasses to attract pests, making it attractive to household pets as well.[5]

Metaldehyde is effective on pests by contact or ingestion and works by limiting the production of mucus in mollusks making them susceptible to dehydration.[6]

Metaldehyde products were used to control the invasive African land snail population in Miami-Dade County in Florida. Experimental use permits from the U.S. Environmental Protect Agency authorized the application amount and usage in residential areas.[6]

Due to the contamination of drinking water by metaldehyde's use in agriculture, a specialist organisation was established in 2008 called "The Metaldehyde Stewardship Group (MSG)".

On 19 December 2018, the British government banned the use of metaldehyde slug pellets outdoors from spring 2020; after this date it would only be legal to use it in permanent greenhouses.[7] In July 2019, the ban was overturned after the High Court in London agreed with a challenge to its legality. Metaldehyde pellets returned to the UK market until 18 September 2020, when the British government banned the use of metaldehyde slug pellets outdoors after 31 March 2022.[8]

Other uses

[edit]Metaldehyde was originally developed as a solid fuel.[9] It is still used as a camping fuel, also for military purposes, or solid fuel in lamps. It may be purchased in a tablet form to be used in small stoves, and for preheating of Primus type stoves. It is sold under the trade name of "META" by Lonza Group of Switzerland; it can be included in the field ration of some nations.

Safety and toxicity to pets and humans

[edit]Metaldehyde has a toxicity profile identical to that for acetaldehyde, being mildly toxic[10] and a respiratory irritant at the 50 ppm level. In terms of water safety, during periods of rainfall metaldehyde pellets become agitated and can seep into natural water courses. The European Commission restricts metaldehyde levels to 0.1 μg/L in drinking water.[11]

Metaldehyde-containing slug baits are banned in some countries as they are toxic to dogs and cats and disturb the natural ecosystems.[2][12] There is no antidote or specific treatment plan for metaldehyde poisoning. Symptoms of poisoning in dogs and cats vary and are very similar to poisonings by other substances, however they can include tremors, drooling, hyperthermia, vomiting, and restlessness. If left untreated, symptoms will proceed to seizures and death within days. Severity of symptoms and speed of onset depend on the quantity ingested and the other contents of the stomach which affect absorption.[13]

A diagnosis can be made by an analysis of stomach contents, which tend to have an apple cider vinegar odor, as well as a history of exposure to the chemical. Treatment includes IV fluids, sedation, lowering body temperature, and purging of stomach contents with charcoal. Prompt and aggressive medical attention after a poisoning may make a full recovery possible within 2–3 days.[13]

Due to this toxicity, pet owners may want to investigate alternatives which are not as toxic to pets, such as ferric sodium EDTA or aluminium sulfate.[14] The metaldehyde tablets resemble candies and do not taste bad, making accidental ingestion possible by children or even by adults unaware of their true nature. Their use was popular during the interwar period and several cases of poisoning resulted.[15] Baits may contain a bitterant to prevent accidental consumption by pets or children.

Oral ingestions of metaldehyde have been described in adults attempting suicide; amongst them, the majority experienced gastrointestinal or neurological symptoms. When compared to humans with accidental ingestion of metaldehyde, those attempting suicide tend to be symptomatic (for example reduced concentrations of GABA causing seizures) and often require care in an intensive care unit and/or long-term hospitalization.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Metaldehyde". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ a b Joyner, Lisa (2022-04-01). "Slug pellets officially banned in the UK". Country Living. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- ^ Marc Eckert, Gerald Fleischmann, Reinhard Jira, Hermann M. Bolt, Klaus Golka "Acetaldehyde" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_031.pub2.

- ^ PubChem. "Metaldehyde". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ^ "Metaldehyde Toxicity Slug Bait Poisoning | VCA Animal Hospitals". vcahospitals.com. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ^ a b Armstrong, John H. (January 18, 2013). "Frequently Asked Questions about Metaldehyde For Controlling Snails and Slugs" (PDF). Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Restrictions on the use of metaldehyde to protect wildlife, UK Government, 19 December 2018

- ^ Outdoor use of metaldehyde to be banned to protect wildlife, UK Government, 18 September 2020

- ^ Eschenmooser, Walter (June 1997). "100 Years of Progress with LONZA". CHIMIA. 51 (6): 259–269. doi:10.2533/chimia.1997.259. S2CID 100485418.

- ^ Toxicology of metaldehyde

- ^ Maher S; et al. (2016). "Direct Analysis and Quantification of Metaldehyde in Water using Reactive Paper Spray Mass Spectrometry". Scientific Reports. 6 35643. Bibcode:2016NatSR...635643M. doi:10.1038/srep35643. PMC 5073298. PMID 27767044.

- ^ "Pests in Gardens and Landscapes". University of California, Davis. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ a b "Metaldehyde Poisoning in Animals - Toxicology". Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ^ "Slugging Out Spring". Dr. Heidi Houchen, DVM. Archived from the original on 2012-07-18.

- ^ Miller, Reginald (December 1928). "Poisoning by "Meta Fuel" Tablets (Metacetaldehyde)". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 3 (18): 292–295. doi:10.1136/adc.3.18.292. PMC 1975025. PMID 21031743.

- ^ Tan YJ.; et al. (2022). "Acute metaldehyde poisoning from ingestion: clinical features and implications for early treatment". Acute Medicine & Surgery. 9. doi:10.1002/ams2.766. PMC 9209800. PMID 35769386.

External links

[edit]- National Pesticide Information Center (NPIC) Information about pesticide-related topics.

- Get Rid of Slugs and Snails, Not Puppy Tails! Case Profile - National Pesticide Information Center

- Slugs and Snails - National Pesticide Information Center

- WHO/FAO Data sheet at inchem.org

- Slug controls (on Wikibooks)

- Metaldehyde in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)

Metaldehyde

View on GrokipediaMetaldehyde is the cyclic tetramer of acetaldehyde, an organic compound with the molecular formula C₈H₁₆O₄, appearing as a white crystalline solid that is insoluble in water and highly flammable.[1][2] It is commercially produced by the polymerization of acetaldehyde and serves primarily as a molluscicide, disrupting mucus production in slugs and snails to impair their mobility and digestion, thereby controlling these pests in agricultural and horticultural settings.[2][3] While effective against target gastropods, metaldehyde exhibits moderate acute toxicity to mammals upon ingestion, inducing neurological symptoms such as tremors, ataxia, seizures, and potentially death at doses exceeding 400 mg/kg, with particular risks documented in dogs from bait exposure.[4][5] Environmentally, its stability under hydrolysis and photolysis contributes to persistence in soil and water, posing hazards to aquatic organisms and leading to regulatory scrutiny, including mitigation requirements by agencies like the EPA to curb runoff into water supplies.[6][7] Historically also used as a solid fuel in portable heaters, its pesticide applications dominate, though incidents of non-target poisoning and ecological concerns have prompted bans or restrictions in regions prioritizing water quality over pest control efficacy.[8][9]

Chemical Identity and Synthesis

Molecular Structure

Metaldehyde possesses the molecular formula C₈H₁₆O₄ and constitutes the cyclic tetramer of acetaldehyde (CH₃CHO), formed by the polymerization of four acetaldehyde units linked through acetal-like ether bonds.[1][10] Its systematic IUPAC name is 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl-1,3,5,7-tetraoxocane, reflecting the eight-membered heterocyclic ring (1,3,5,7-tetraoxocane) substituted with methyl groups at the even-numbered positions.[11][12] The core structure comprises an alternating sequence of four oxygen and four carbon atoms in a ring, where each ring carbon bears a methyl substituent, yielding a symmetric, crown-ether-like arrangement that favors chair or boat conformations for stability.[1] This configuration distinguishes metaldehyde from the trimeric paraldehyde, which forms a six-membered ring, and contributes to its relatively high melting point and volatility compared to monomeric acetaldehyde.[10] The molecule exhibits no defined stereocenters in its standard depiction, though polymerization can yield mixtures of stereoisomers.[13]Production Methods

Metaldehyde is synthesized industrially via the acid-catalyzed polymerization of acetaldehyde, forming a cyclic tetramer under controlled low-temperature conditions to favor the tetrameric product over the more common trimeric paraldehyde.[1][14] The process typically employs chilled mineral acids, such as sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid, or hydrogen bromide in combination with alkaline earth metal halides like calcium bromide, at temperatures ranging from -40°C to 15°C.[15][1] In one established method, acid-free acetaldehyde is diluted with C4-C8 n-hydrocarbons prior to polymerization to enhance selectivity and yield.[16] Yields of metaldehyde are generally moderate, as the reaction concurrently produces significant quantities of paraldehyde, requiring separation techniques such as distillation or crystallization to isolate the solid tetramer.[1] Alternative catalytic approaches, including rare earth metal halides or phosphoric acid, have been explored to optimize tetramer formation, though mineral acid methods remain predominant in commercial production.[15][17]Physical and Chemical Properties

Appearance and Solubility

Metaldehyde is a white crystalline solid at room temperature, often exhibiting a powdery texture and possessing a mild, menthol-like odor.[1][18] In commercial formulations, it is commonly processed into pellets, granules, or powders to facilitate handling and application as a molluscicide.[18] The compound demonstrates low solubility in water, with reported values ranging from 0.02% w/w (approximately 200 mg/L) at 20°C to 260 mg/L at 30°C, rendering it practically insoluble under typical environmental conditions.[1][18][19] This limited aqueous solubility contributes to its persistence in soil and reduced leaching potential compared to more hydrophilic pesticides. In contrast, metaldehyde exhibits moderate to good solubility in select organic solvents, including benzene, chloroform, ethyl alcohol (soluble), toluene (530 mg/L at 20°C), and methanol (1730 mg/L), while showing insolubility or sparing solubility in acetone, acetic acid, ether, and carbon disulfide.[10][18][20]Stability and Reactivity

Metaldehyde is chemically stable under normal storage and handling conditions at ambient temperatures but undergoes depolymerization upon heating, occurring slowly at elevated temperatures and rapidly above 80 °C to yield acetaldehyde.[21][22] Moisture induces very slow hydrolysis of the compound.[23] The material is light-sensitive, which may contribute to gradual degradation over time.[24] As a flammable solid, metaldehyde poses fire hazards, with autoignition occurring at approximately 580 °C; ignition produces irritating fumes including acetaldehyde.[1][24] It can react with strong oxidizing agents, potentially leading to vigorous reactions or combustion.[1][10] Hazardous decomposition products include acetaldehyde, paraldehyde, and further acetic acid under prolonged heating or in the presence of acids.[25] Conditions to avoid encompass ignition sources, dust generation, excessive heat, and contact with incompatibles such as oxidizers.[21]

Historical Development

Discovery and Early Research

Metaldehyde, the cyclic tetramer of acetaldehyde with the formula (CH₃CHO)₄, was first synthesized and characterized by the German chemist Justus von Liebig in 1835 through the acid-catalyzed polymerization of acetaldehyde.[26] [27] This discovery occurred during Liebig's investigations into aldehyde chemistry, where he observed the formation of white, crystalline prisms from acetaldehyde treated with sulfuric acid, distinguishing it from the monomeric form.[14] Early structural analysis confirmed its tetrameric nature, though full elucidation of its cyclic configuration awaited later spectroscopic advancements.[28] In the early 20th century, metaldehyde's practical utility emerged beyond pure chemistry, with its adoption as a solid fuel under the trade name "Meta-fuel" by around 1928, leveraging its high energy density and clean-burning properties for applications like portable stoves.[29] Patents for its industrial-scale production, such as those filed by Emil Lüscher and Theodor Lichtenhan in the 1920s, detailed optimized polymerization methods using concentrated sulfuric acid to yield coherent blocks suitable for fuel.[30] [31] These developments focused on manufacturing efficiency rather than novel biological applications, reflecting metaldehyde's initial inertness in non-combustive contexts. The shift toward pesticidal research began in the 1930s amid agricultural needs for slug and snail control, with British researchers F. S. Gimingham and W. H. Newton proposing its molluscicidal potential in 1937 after observing lethal effects on gastropods via dehydration and neuromuscular disruption.[14] [26] Initial field trials in the late 1930s demonstrated efficacy against species like Agriolimax agrestis, where metaldehyde acted as both a contact toxin and stomach poison, prompting its commercial introduction as a bait in 1936 and widespread adoption in slug pellets by the early 1940s.[32] Early toxicity studies emphasized its selectivity over broad-spectrum alternatives, though concerns about secondary poisoning in wildlife emerged from these foundational experiments.[33]Commercial Introduction and Adoption

Metaldehyde's potential as a molluscicide was first systematically explored and proposed in 1937 by researchers Gimingham and Newton, who identified its efficacy against slugs through early toxicity tests.[26] This followed its chemical discovery as a cyclic tetramer of acetaldehyde in 1835 by Justus von Liebig, though initial applications focused on non-pesticidal uses like solid fuel.[34] Commercial development accelerated in the late 1930s, with production involving the polymerization of acetaldehyde under acidic conditions to yield the stable tetrameric form suitable for formulation into baits.[2] By the early 1940s, metaldehyde entered the market as pelletized slug baits, marking its transition to widespread agricultural application.[27] Lonza, a key manufacturer, commercialized it under the brand Meta®, targeting pests in crops vulnerable to gastropod damage such as cereals, oilseed rape, and vegetables.[27] Its adoption surged in temperate regions like Europe, where slug pressures necessitated reliable control measures; in the United Kingdom, it quickly became the dominant molluscicide due to superior field performance over alternatives like arsenicals or lime-based treatments.[28] In the United States, federal registration occurred in 1967, enabling labeled use on turf, ornamentals, berries, citrus, and vegetables, which broadened its uptake in North American agriculture and horticulture.[35] Global adoption peaked mid-century, with formulations typically at 1-5% active ingredient in bran- or grain-based pellets to enhance palatability and dispersal.[1] Despite early enthusiasm for its contact and stomach poison action, usage patterns emphasized targeted applications to minimize non-target exposure, though its persistence in soil and runoff later prompted stewardship programs.[36]Primary Applications

Molluscicidal Use in Agriculture and Gardening

Metaldehyde is employed as a contact and stomach poison in pelleted baits, typically containing 1-5% active ingredient, to control slugs and snails that damage crops such as cereals, oilseed rape, vegetables, and ornamentals in agricultural fields and home gardens.[37] These baits are broadcast onto soil surfaces during periods of high pest activity, often in moist conditions when molluscs are most active, attracting them via incorporated food lures like bran or bran derivatives.[38] Application rates vary by formulation and pest pressure, commonly ranging from 5-40 kg/ha in agriculture, with lower doses (e.g., 2.5 g/m²) tested in garden settings for efficacy against species like the brown garden snail (Cornu aspersum).[39] [40] Field trials have demonstrated metaldehyde's effectiveness in reducing slug and snail damage, with applications achieving up to 100% mortality in controlled tests against pests like the giant African snail and common garden slugs.[41] [42] For instance, in moderately infested areas, doses of 120 kg/ha controlled snail densities exceeding 2000/m² in both dry and wet conditions, outperforming some iron phosphate alternatives under frequent irrigation.[43] [44] Novel delivery systems, such as Baitchain—metaldehyde pellets strung on cords tied to tree trunks—have shown comparable or superior control of climbing snails in orchards compared to traditional surface scattering, even at reduced concentrations.[45] However, efficacy depends on environmental factors like rainfall, which can dilute baits or enhance mollusc foraging, and repeated applications may be needed for persistent infestations.[46] Regulatory restrictions have curtailed metaldehyde's availability in certain regions due to concerns over runoff into water sources and non-target toxicity, despite its proven pest control benefits. In Great Britain, outdoor use was banned effective March 31, 2022, following detections in raw drinking water exceeding safety thresholds, with no emergency extensions granted as of 2025; possession or use of pre-ban stocks imported illegally remains prohibited.[47] [48] [49] In the European Union, approvals persist in multiple member states for agricultural applications, diverging from the UK's post-Brexit policy, while in the United States, metaldehyde baits like Deadline remain recommended for slug control in field crops and gardens by extension services.[50] [51] Growers in restricted areas have shifted to alternatives like ferric phosphate, though studies indicate metaldehyde often provides faster and more reliable knockdown.[44]Non-Pesticidal Applications

Metaldehyde was originally developed and marketed as a solid fuel, known as "solid alcohol," for portable heating applications prior to its recognition as a molluscicide in the 1930s.[52] It burns cleanly with a steady flame, producing no soot, ash, or residue, which makes it advantageous for use in confined spaces.[10] In tablet form, metaldehyde serves as fuel for camping stoves, military field equipment, fire starters, and small portable heaters, often as a substitute for liquid alcohols.[8][10] Concentrations in such products can reach up to 100% metaldehyde in solid fuel or fire starter pellets.[53] These applications leverage its low odor, lightweight nature, and ease of ignition, though usage has declined with the availability of alternative fuels.[54] Rarely, metaldehyde is incorporated into novelty products designed to colorize flames, comprising up to 90% of the formulation in some cases.[53] This pyrotechnic-like use exploits its combustion properties to produce visual effects, but it remains a minor application compared to its fuel role.[53]Mechanism of Action and Efficacy

Biochemical Effects on Target Pests

Metaldehyde exerts its molluscicidal effects primarily through contact and ingestion by target pests such as slugs (Deroceras reticulatum) and snails (Theba pisana, Pomacea canaliculata), inducing symptoms including excessive mucus excretion, paralysis, and eventual death.[37] The compound damages mucus-producing cells in the foot, mantle, and other tissues, leading to hypersecretion that exhausts the mollusc's resources rather than causing direct dehydration.[55] Upon ingestion, metaldehyde is rapidly hydrolyzed to acetaldehyde, which stimulates uncontrolled mucus production and contributes to the pest's demise.[27] Neurotoxic actions are evident in electrophysiological studies, where metaldehyde induces bursting activity and paroxysmal depolarizing shifts in identified motoneurons of the feeding system in snails like Lymnaea stagnalis, disrupting normal neural function and leading to immobilization.[56] At higher concentrations, it acts as a nerve poison, causing excitation or depression of the central nervous system, which manifests as behavioral changes such as hyperactivity followed by paralysis.[57] Biochemical analyses reveal dose- and time-dependent cytotoxicity, including oxidative damage that activates antioxidant enzymes (e.g., superoxide dismutase, catalase) in response to lipid peroxidation and reactive oxygen species generation in snail tissues.[58][37] Enzyme activity alterations further underscore metaldehyde's impact: in exposed snails, acetylcholinesterase inhibition occurs alongside elevated levels of stress-related enzymes like glutathione S-transferase, indicating interference with cholinergic neurotransmission and detoxification pathways.[58] Histopathological examinations confirm cellular damage, including vacuolation and necrosis in mucus glands and neural tissues, supporting both cytotoxic and neurotoxic mechanisms.[58] Despite these observations, the precise molecular targets remain incompletely elucidated, with ongoing research emphasizing metaldehyde's specificity to molluscan physiology over broad-spectrum neurotoxicity seen in vertebrates.[58][37]Field Efficacy Data and Comparisons to Alternatives

Field trials in agricultural settings, such as apple orchards in South Africa, have demonstrated that metaldehyde applications at concentrations of 40 g/kg—whether via traditional soil-surface pellets or novel bait chains—achieve significant mortality in target snails like Cornu aspersum, with effects observable by day 14 and persisting through day 28 post-application.[45] In greenhouse simulations approximating field conditions, metaldehyde pellets significantly reduced slug (Arion vulgaris) herbivory and biomass compared to untreated controls (p < 0.001), with efficacy enhanced under less frequent watering regimes that limit moisture availability.[44] Potato field trials using multi-application programs (e.g., three treatments timed to canopy closure and rainfall events) confirmed metaldehyde's role in effective slug management, reducing damage to levels comparable to integrated programs.[59] Comparisons to iron phosphate (ferric phosphate) reveal metaldehyde's advantages in speed and consistency under drier or moderate moisture conditions, where it induces rapid paralysis and dehydration in slugs within hours, outperforming iron phosphate's slower mechanism that relies on ingestion and may take days to kill.[60] Both compounds reduce slug herbivory and weight significantly versus controls in controlled environments, but metaldehyde's performance declines more in high-humidity or low-temperature scenarios, while iron phosphate maintains viability as an alternative in potato systems with repeated applications, albeit with potentially lower immediate mortality rates.[44][59] Biological alternatives like nematodes (Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita) show negligible impact on slug damage or populations (p > 0.05), rendering them inferior for standalone field control.[44]| Molluscicide | Key Efficacy Metric | Conditions/Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metaldehyde | >80% snail mortality by day 14 at 40 g/kg | Apple orchard, combined application methods | [45] |

| Metaldehyde | Significant herbivory reduction (p < 0.001) | Less frequent watering enhances effect | [44] |

| Iron Phosphate | Comparable damage control in multi-apps | Viable metaldehyde substitute in potatoes | [59] |

| Iron Phosphate | Slower kill (days vs. hours); effective in cold/wet | Less reliable in rain-prone fields | [60] |

| Nematodes | No significant reduction (p > 0.5) | Ineffective alone vs. chemical baits | [44] |