Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

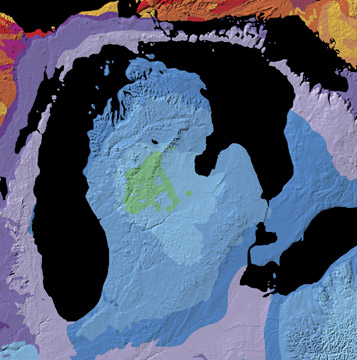

Michigan Basin

View on Wikipedia

The Michigan Basin is a geologic basin centered on the Lower Peninsula of the U.S. state of Michigan. The feature is represented by a nearly circular pattern of geologic sedimentary strata in the area with a nearly uniform structural dip toward the center of the peninsula.

Geology

[edit]The basin is centered in Gladwin County where the Precambrian basement rocks are 16,000 feet (4,900 m) deep. Around the margins, such as under Mackinaw City, Michigan, the Precambrian surface is around 4,000 feet (1,200 m) below the surface. This 4,000-foot (1,200 m) contour on the basement surface clips the northern part of the Lower Peninsula and continues under Lake Michigan along the west. It crosses the southern counties of Michigan and continues to the north beneath Lake Huron.

On the north in the Canadian Shield, which includes the western part of Michigan's Upper Peninsula, Precambrian rocks are exposed at the surface. The eastern margins of Wisconsin along Green Bay are along the margins of the basin, while Precambrian rocks crop out to the west in central Wisconsin. The northeastern margin of Illinois around Chicago is on the southwestern margin of the basin. The southeast-striking Kankakee Arch continuation of the Cincinnati Arch forms the southwest boundary of the basin underlying northeastern Illinois and northern Indiana. To the east, the Findlay Arch forms the southeast margin of the basin as it strikes to the northeast across northwestern Ohio, under the bed of Lake Erie and on as the Algonquin Arch through the southwestern prong of Ontario. The Wisconsin Arch forms the western boundary of the basin.

The rocks of the basin include Cambrian-Ordovician sandstones and carbonate rocks around the margins and at depth. Silurian-Devonian dolomites and limestones with Carboniferous (Mississippian and Pennsylvanian) strata are located basinward or above filling in the center. A veneer of Jurassic sediments is found in the center of the basin at the surface.

The basin appears to have subsided concurrently with sediment infilling. These sediments were found to be mainly shallow-water sediments, many of which are richly fossiliferous. The location was on a geologically passive portion of crust. The development of the basin and the surrounding arches were likely affected by the tectonic activity of the long-term Appalachian orogeny several hundred miles to the south and east.

Within the Precambrian rocks beneath and just west of the center of the basin lies a generally north to northwest trending linear feature that appears to be an ancient rift in the Earth's crust. This rift appears to be contiguous with the rift zone under Lake Superior. This, the Midcontinent Rift System, turns west under Lake Superior and then southwest through southern Minnesota, central and western Iowa and southeastern Nebraska and into eastern Kansas.

Natural resources

[edit]Some minerals that have been mined from rocks in the basin include halite and gypsum. Halite (rock salt) occurs in beds of the Salina Formation (Silurian) and the Detroit River Group (Devonian). The Detroit salt mine has mined rock salt from beneath the Detroit metropolitan area since 1906.[2] Brine recovered from wells in the Michigan basin has been used as a commercial source of potassium salts, bromine, iodine, calcium chloride, and magnesium salts.[3]

Oil and gas

[edit]Key Information

The rocks of the Michigan Basin are the source of commercial quantities of petroleum. The most actively drilled-for source of natural gas in recent years has been shale gas from the Devonian Antrim Shale in the northern part of the basin.

The Michigan basin extends into Ontario, Canada, where oil and gas regulators are studying its potential. It is considered to be one of "America's most promising oil and gas plays."[4] In May 2010, a Michigan public land auction attracted the attention of the largest North American natural gas corporations, such as Encana (now Ovintiv) and Chesapeake Energy. From 2008 through 2010, Encana accumulated a "large land position" (250,000 net acres)[4] in a shale gas play in Michigan's Middle Ordovician Collingwood shale. Encana focused activities in Cheboygan, Kalkaska, and Missaukee counties in Michigan's northern Lower Peninsula.[5] Natural gas is produced from both Utica and Collingwood shale (called Utica Collingwood). Collingwood is a shaly limestone about 40 feet thick that lies just above the Ordovician Trenton formation. Utica shale overlies the Collingwood.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Blakey, Ron. "Paleogeography and Geologic Evolution of North America". Global Plate Tectonics and Paleogeography. Northern Arizona University.

- ^ Manos, E.Z. (February 2003). "Detroit salt mine-past and future". pp. 15–19.

- ^ George I. Smith and others (1973) Evaporites and brines, in United States Mineral Resources, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 820, p.197-216.

- ^ a b Grow, Brian; Schneyer, Joshua; Roberts, Janet (June 25, 2012). "Special Report: Chesapeake and rival plotted to suppress land prices". Reuters. Gaylord, Michigan.

- ^ a b Petzet, Alan (May 7, 2010). "Explorations: Michigan Collingwood-Utica gas play emerging". Oil & Gas Journal. Houston, Texas.

External links

[edit]Michigan Basin

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Extent

The Michigan Basin is an intracratonic sedimentary basin spanning approximately 122,000 square miles underlain by Paleozoic rocks, primarily within the Lower Peninsula of Michigan but extending into northeastern Indiana, northwestern Ohio, eastern Wisconsin, and adjacent areas of Ontario, Canada.[2] This extent encompasses much of the state's interior, bounded by regional arches and shields including the Canadian Shield to the north and the Findlay Arch to the southeast.[2] The basin's center lies in Gladwin County, central Michigan, where the depth to the Precambrian basement reaches about 16,000 feet, marking the thickest accumulation of sedimentary strata.[3] Toward the margins, such as near Mackinaw City along the northern edge, the basement shallows to roughly 4,000 feet, reflecting the basin's saucer-like geometry.[3] The Michigan Basin overlies the Midcontinent Rift System, a late Precambrian feature comprising Keweenawan-age clastic rocks and rift-related structures that partly define its peripheral boundaries.[2][10]Physical Features

The surface of the Michigan Basin is predominantly covered by unconsolidated Pleistocene glacial deposits, resulting from multiple advances of the Laurentide Ice Sheet during the Quaternary Period.[11] These deposits, including till, sand, gravel, and clay, reach thicknesses of up to 1,200 feet in places and form the foundational layer over the underlying Paleozoic bedrock.[12] The glaciation, particularly the Wisconsinan stage from approximately 55,000 to 10,000 years ago, sculpted the landscape into flat to gently rolling plains, with characteristic landforms such as moraines, drumlins, and outwash plains.[13] Moraines, like the Valparaiso and Port Huron border moraines, appear as arcuate ridges of till marking former ice margins, while drumlins—streamlined, teardrop-shaped hills—cluster in areas such as the Grand Traverse Bay region, oriented parallel to ice flow directions.[11] Outwash plains, composed of sorted sands and gravels deposited by meltwater, dominate broader lowlands and contribute to the region's subdued relief, with elevations generally ranging from 600 to 1,400 feet above sea level.[14] The Michigan Basin encompasses significant portions of the Great Lakes system, including Lakes Michigan, Huron, and Erie, where the subsurface basin structure subtly influences lakebed topography and sediment distribution.[11] Glacial erosion deepened these lake basins by scouring softer Paleozoic formations, resulting in maximum depths of 750 feet in Lake Huron, 923 feet in Lake Michigan, and 210 feet in Lake Erie, with lakebed sediments primarily consisting of glacial till, clays, and sands derived from the surrounding drift.[15][16][17] The basin's elliptical geometry, centered beneath the Lower Peninsula, contributes to the lakes' irregular shorelines and sediment accumulation patterns, as meltwater channels and proglacial lakes deposited layered clays and silts on the lake floors during deglaciation around 11,000 to 9,000 years ago.[18] Major river systems within the Michigan Basin, such as the Grand, Saginaw, and Maumee Rivers, originate in the glacial landscapes and drain eastward and northward into the Great Lakes, shaping regional hydrology through their interactions with surface and shallow groundwater.[19] The Grand River, Michigan's longest at 261 miles, flows westward from glacial till plains to Lake Michigan, carving valleys through outwash deposits and facilitating sediment transport to the lake.[11] The Saginaw River system, draining a 8,500-square-mile watershed of moraine-dotted lowlands, empties into Saginaw Bay of Lake Huron, where it deposits suspended sediments and connects to underlying aquifers via permeable glacial sands.[20] Similarly, the Maumee River, traversing the basin's southern margin in Ohio and Indiana, discharges into western Lake Erie, influencing lake hydrology with peak flows that recharge shallow groundwater in outwash aquifers along its course.[21]Geological History

Tectonic Evolution

The Michigan Basin's tectonic foundations trace back to the Mesoproterozoic Era, when it formed as part of the Midcontinent Rift System approximately 1.1 billion years ago. This extensive rift, spanning over 3,000 kilometers across central North America, represented a failed attempt at continental breakup driven by extensional forces, possibly linked to a mantle plume. The rifting process involved voluminous igneous activity and sedimentation, but ultimately stalled, leaving behind a weakened crustal structure beneath what would become the basin. This inherited weakness predisposed the region to later subsidence without requiring ongoing extension.[22][23] During the Paleozoic, the basin's evolution was profoundly shaped by the Appalachian Orogeny, a major collisional event associated with the assembly of the supercontinent Pangaea. This orogeny, spanning the Devonian through Permian periods, generated far-field stresses that propagated into the cratonic interior, causing peripheral uplift around the basin margins and episodic subsidence within its center. The resulting isostatic adjustments and lower crustal weakening accelerated sedimentation rates, with subsidence pulses correlating directly to orogenic phases, such as the Middle Ordovician and Acadian events. These dynamics transformed the rift-related depression into a mature intracratonic basin filled with thick Paleozoic sequences.[24][25] Following the Paleozoic, the Michigan Basin entered a phase of relative tectonic stability, characteristic of cratonic interiors, with only minor reactivations tied to distant Mesozoic rifting events associated with the opening of the Atlantic Ocean. This quiescence allowed for gradual thermal subsidence, preserving a thin veneer of Jurassic nonmarine sediments in the basin's central areas, where slow downwarping prevented erosion. No major tectonic disruptions occurred, underscoring the basin's role as a long-lived, stable depocenter amid broader continental adjustments.[26][27]Formation Processes

The Michigan Basin formed primarily through thermal subsidence of passive continental crust beginning in the Cambrian period, approximately 540 million years ago, as the North American craton stabilized following earlier tectonic events. This initial subsidence was driven by the cooling and contraction of the lithosphere after minor extensional rifting, leading to isostatic adjustment that created accommodation space for sediments. Over the subsequent Paleozoic era, the process involved episodic acceleration, particularly due to the loading of accumulating sediments, which further depressed the crust through flexural responses.[28][29] Shallow epicontinental seas periodically inundated the region for more than 300 million years, from the Cambrian through the Permian, fostering the deposition of up to 5 kilometers of largely undeformed sediments in a nearly circular intracratonic basin roughly 400 kilometers in diameter. These seas, part of broader transgressive-regressive cycles across Laurentia, supplied fine-grained clastics, carbonates, and evaporites that filled the subsiding depocenter. The basin's saucer-like geometry reflects the progressive thickening of sediments toward the center, with dips averaging 1-2 degrees.[28][30][29] The dominant subsidence mechanism combined thermal subsidence due to post-rift lithospheric cooling with flexural loading induced by peripheral orogenies, such as the Taconic and Acadian events to the east, which transmitted far-field stresses and added sediment loads to the basin margins. Thermal contraction models indicate that lithospheric cooling provided the long-term subsidence trend, while sediment infilling amplified it through self-loading, maintaining relatively stable subsidence rates of about 10-20 meters per million years in the basin center. This interplay preserved the basin's intracratonic character without significant internal deformation. The structure inherits some influence from underlying Precambrian rift features.[28][29][26]Stratigraphy and Rock Types

Paleozoic Sequence

The Paleozoic sequence in the Michigan Basin represents a thick accumulation of sedimentary rocks, primarily carbonates, evaporites, and clastics, deposited in a subsiding intracratonic basin from approximately 541 to 299 million years ago, spanning the Cambrian through Pennsylvanian periods. This sequence, reaching up to 16,000 feet in the basin center, records repeated marine transgressions and regressions influenced by eustatic sea-level changes and regional tectonics. Basal units consist of transgressive sands and shales overlain by extensive carbonate platforms and evaporitic deposits, with deposition ceasing in the late Carboniferous due to diminished subsidence.[31] The Cambrian-Ordovician interval forms the basal part of the sequence, characterized by siliciclastic sandstones transitioning upward into carbonates, with a total thickness ranging from less than 500 to more than 3,500 feet in the basin subsurface. The lowermost unit, the Mount Simon Sandstone, comprises medium- to coarse-grained, quartz-rich sandstone deposited in shallow marine to nearshore environments, reaching about 300 feet thick in southeastern Michigan. Overlying it, the Eau Claire Formation includes interbedded sandstone, shale, and dolomite, with maximum thicknesses of 830 feet centrally, reflecting tidal and lagoonal settings. The sequence grades into Ordovician carbonates of the Black River Group, consisting of limestones and dolomites up to 965 feet thick, indicative of shallow shelf deposition.[32] Silurian to Devonian strata dominate the middle Paleozoic fill, featuring evaporites, dolomites, limestones, and shales, with the Silurian reaching up to 4,000 feet thick in the basin center. The Niagaran Series, a key Silurian unit, comprises dolomites and limestones with prominent fossil-rich reefs—algal-stromatoporoid buildups up to 500 feet in relief along basin margins—deposited on carbonate platforms, with thicknesses ranging from 100 to over 1,000 feet. The overlying Salina Formation includes thick halite and anhydrite evaporites, such as the A-1 and B evaporite units, formed in restricted saline basins, contributing significantly to the sequence's cyclic nature. Devonian rocks, including the Antrim Shale (dark organic-rich shales) and associated limestones and dolomites, overlie the Silurian with local unconformities, recording continued shallow marine to deeper basinal conditions.[31] The Carboniferous upper sequence is notably thin compared to underlying units, consisting of sandstones, shales, and minor limestones, marking the end of major depositional activity around 300 million years ago as subsidence waned. Mississippian rocks, represented by the Bayport Limestone, include interbedded sandstones, limestones, shales, and siltstones in nearshore to shallow marine settings, with thicknesses up to 75 feet. Pennsylvanian units, such as the Parma and Hemlock Lake Formations, feature sandstones, shales, and thin coals in fluvial and swamp environments, with individual formations 30 to 200 feet thick but overall comprising less than 1,000 feet basin-wide. Permian strata are minimal or absent, reflecting tectonic stabilization.[33]Mesozoic and Cenozoic Cover

The Mesozoic sedimentary cover overlying the Paleozoic sequence in the Michigan Basin is thin and discontinuous, with no significant Jurassic or Cretaceous strata preserved. Thin red beds, previously interpreted as Middle Jurassic (Ionia Formation) but reclassified as late Pennsylvanian based on recent fossil and detrital zircon studies (e.g., Rine et al., 2013; McLaughlin et al., 2018), comprise red sandstones, shales, clays, and minor gypsum and limestone, preserved in limited subsurface occurrences in central and west-central areas.[34][35] They are interpreted as continental deposits equivalent to broader Appalachian red bed sequences, but restricted to a small central basin area due to extensive post-depositional erosion during the late Mesozoic.[36][12] Overall, Mesozoic strata are absent or eroded across much of the basin, reflecting tectonic uplift and exposure following Paleozoic subsidence.[37] Cretaceous rocks are largely absent from the Michigan Basin, with only minimal potential for marine sands preserved in southern extensions near the basin margins, though no significant exposures or well-documented units are recognized.[38] This gap is attributed to regional erosion and non-deposition during the Cretaceous, as the basin was likely emergent and subject to weathering.[13] The Cenozoic cover is dominated by unconsolidated Pleistocene glacial and post-glacial deposits, which blanket the entire basin and obscure underlying bedrock. These include tills, clays, sands, and gravels from multiple Laurentide Ice Sheet advances, reaching thicknesses of up to 1,000 feet (300 meters) in central lowlands.[2] Holocene sediments are minor, consisting of thin alluvium and lake deposits in modern drainages.[38] This glacial veneer, the only significant Cenozoic record in the basin, resulted from repeated ice sheet incursions during the Quaternary, masking the Paleozoic basement and influencing modern hydrology.[39]Structural Geology

Basin Geometry

The Michigan Basin is an intracratonic sedimentary basin characterized by a nearly circular to slightly oval shape, with a diameter of approximately 400 km and a subtle northwest-southeast elongation.[40] This geometry results in a symmetric, saucer-like profile where strata dip gently toward the center at rates of 25–60 feet per mile (0.3–0.7 degrees).[3][40] Sedimentary thickness increases progressively from about 4,000 feet at the basin margins—such as near Mackinac City—to a maximum of around 16,000 feet (5 km) at the center in Gladwin County, overlying a Precambrian crystalline basement composed primarily of granites and gneisses.[3][40] This depth variation reflects prolonged tectonic subsidence that accommodated Paleozoic deposition without significant structural disruption. The basin's three-dimensional architecture has been delineated through seismic reflection surveys and well data, revealing concentric isopach contours that highlight the radial thickening of sedimentary layers toward the depocenter.[3][40] These mapping techniques confirm the basin's broad, bowl-shaped form and minimal asymmetry.Faults and Folds

The Michigan Basin exhibits a predominantly undeformed interior, characterized by gentle dips of less than 1° toward the basin center, with structural disruptions largely confined to its margins.[41] This relative stability contrasts with peripheral zones where normal faults, inherited from the Precambrian Midcontinent Rift System, have been reactivated during later tectonic events.[42] These faults, often listric in nature and dipping moderately, form part of the Mid-Michigan Rift Zone and include structures like the Bowling Green fault system in southeastern Michigan, which bounds the Lucas-Monroe monocline with dips up to 300 feet per mile.[43] Reactivation occurred primarily during Paleozoic compressional phases, inverting some normal faults and contributing to localized horst and graben features along the basin's northern and eastern peripheries.[42] Minor anticlinal folds are evident near the basin's Appalachian margin, resulting from far-field orogenic compression during the Appalachian orogenies.[25] These folds, such as the Howell Anticline and en echelon structures like the West Branch Anticline, display asymmetrical profiles with amplitudes reaching up to 500 feet and closures exceeding 400 feet in some cases.[44] They trend northwest-southeast, parallel to regional stress fields, and represent shear folds formed in response to Late Paleozoic tectonic loading from the east, without significant basement involvement in the folding process.[45] Flexural interactions between the adjacent Appalachian Basin and the cratonic interior amplified these deformations, influencing subsidence patterns but not altering the basin's overall saucer-like geometry.[25] Fracture systems within Devonian carbonates, particularly in formations like the Dundee Limestone, play a key role in enhancing rock permeability for fluid migration.[46] These fractures form systematic sets oriented SE-NW, NE-SW, E-W, and N-S, with the SE-NW and E-W sets linked to Appalachian orogenic compression and subsequent hydrothermal dolomitization.[42] In the central basin, fractured hydrothermal dolomites account for substantial hydrocarbon reservoirs, where vuggy porosity and interconnected fractures increase effective permeability by orders of magnitude compared to matrix rock.[46] Calcite twin-strain analyses confirm low-strain deformation (e1 values around -0.14 to -0.80), indicating brittle failure under regional stress rather than ductile folding.[42]Natural Resources

Evaporites and Minerals

The Michigan Basin hosts significant evaporite deposits, primarily in the Silurian Salina Formation and the Devonian Detroit River Group, where thick halite (rock salt) beds formed through evaporation in restricted marine basins during periods of limited seawater circulation and high aridity.[47] In the Salina Formation, individual halite beds reach thicknesses of 400 to 1,600 feet, with aggregate evaporite sequences (including halite, anhydrite, and gypsum) exceeding 1,200 feet near the basin's periphery and up to 2,000 feet centrally.[48] Similarly, the Detroit River Group's Lucas Formation contains halite beds with aggregate thicknesses over 400 feet in the central basin, including individual beds exceeding 100 feet, also deposited in evaporative sabkha-like environments.[49] Associated with these halite deposits are other evaporite minerals, notably gypsum, which occurs in beds up to 200 feet thick within the Salina Formation, often interbedded with dolomite and shale.[50] Brine processing from these evaporites yields potash (primarily sylvite in the Salina A-1 Evaporite, with beds up to 30 feet thick), bromine (as magnesium bromide in formation waters), and magnesium salts (such as magnesium chloride), extracted commercially from associated hypersaline brines in the basin's central regions.[51][52] Beyond evaporites, the basin's Devonian stratigraphic units, such as the Dundee and Rogers City formations, contain high-purity limestone and dolomite deposits that serve as key non-hydrocarbon mineral resources. These carbonates, with low impurities in iron, alumina, and silica, are quarried for uses in construction aggregates, chemical manufacturing (e.g., calcium carbonate production), and as fillers in asphalt and concrete.[53][54]Hydrocarbons

The Michigan Basin has been a significant hydrocarbon province since the late 19th century, with production primarily from Paleozoic sedimentary rocks. Natural gas and oil are generated from organic-rich source rocks, trapped in various reservoir types, and extracted through both conventional and unconventional methods. Cumulative hydrocarbon production from the basin exceeds 1.34 billion barrels of oil and 8.2 trillion cubic feet of natural gas as of 2017, reflecting its long history of development beginning in the 1870s for oil and 1925 for substantial gas output.[55] Annual production has since declined, with approximately 5 million barrels of oil and 50 billion cubic feet of gas in 2023.[56] Major source rocks include the Devonian Antrim Shale, which generates biogenic gas through microbial processes in its organic-rich black shales, and the Ordovician Collingwood and Utica Shales, which produce thermogenic hydrocarbons via thermal maturation of kerogen. The Antrim Shale, with total organic carbon content averaging 2-10% in its gas-prone intervals, has been the dominant source for natural gas, accounting for over 80% of Michigan's production in recent decades and yielding nearly 3.4 trillion cubic feet cumulatively through 2014 via more than 11,000 wells.[57][58] The Collingwood/Utica interval, characterized by siliceous shales with higher thermal maturity in the basin's deeper parts, serves as both a source and seal for deeper thermogenic gas and associated oil, with exploration ongoing in these unconventional plays.[2] Total gas production from the basin exceeded 8 trillion cubic feet as of 2017, driven largely by these sources.[55] Key reservoirs encompass the Silurian Niagaran reefs, which host conventional oil traps in porous carbonate buildups, and the uppermost Devonian to lowermost Mississippian Berea Sandstone, which forms stratigraphic traps with high-porosity quartz sandstones. The Niagaran pinnacle reefs, numbering over 1,200 fields, have produced more than 490 million barrels of oil and 2.9 trillion cubic feet of gas, benefiting from excellent reservoir quality with porosities up to 20% in vuggy dolomites.[59] The Berea Sandstone, with its clean, well-sorted sands deposited in a shallow marine environment, has yielded oil from conventional vertical wells since 1925 but has seen revitalization through horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing in unconventional plays, enhancing recovery in low-permeability zones.[60][61] Unconventional development in source rocks like the Antrim and Collingwood/Utica also relies on horizontal drilling to access extensive lateral extents. Structural traps, including gentle folds and minor faults, have facilitated hydrocarbon accumulation in these reservoirs by providing closure.[2] Cumulative oil production from the Michigan Basin totals over 1.3 billion barrels as of 2017, with the peak occurring in the mid-20th century around 35-40 million barrels annually during the 1970s and early 1980s, before declining due to maturation of major fields.[55][8] Despite the decline, ongoing advancements in drilling technology continue to unlock remaining reserves in both conventional and unconventional settings.[61]Economic Importance

Historical Development

The Michigan Geological Survey was established in 1837 by the state legislature to map the region's geology and assess its resources, with the first survey led by Douglass Houghton focusing on mineral potential across the Lower Peninsula.[62] This early effort laid the groundwork for understanding the Michigan Basin's economic viability, though it was interrupted by Houghton's death in 1845. The survey was revived multiple times, including a third iteration in 1869 under Alexander Winchell and later Carl Rominger, which emphasized practical applications such as identifying deposits of iron, copper, and salt to support industrial development.[63] By the 1870s, the survey's work aligned with growing federal interest in resource classification, paving the way for later cooperative arrangements that prioritized economic geology over purely scientific mapping.[63] Exploration of the basin's hydrocarbons gained momentum in the late 19th century, spurred by the 1858 discovery of North America's first commercial oil well at Oil Springs, Ontario, just across the border from Michigan.[64] This find, producing from shallow Devonian strata, ignited speculation in nearby Michigan territories, leading to initial test wells near Port Huron as early as 1870, though these yielded limited results.[65] Commercial production began in the 1880s with the drilling of 22 wells in St. Clair County's Port Huron field starting in 1886, tapping into Dundee Formation reservoirs at depths of approximately 500 to 650 feet and marking the state's entry into the petroleum industry.[66] These early efforts were modest, with total output supporting local needs rather than large-scale export, but they demonstrated the basin's potential for oil accumulation in carbonate rocks. Meanwhile, salt extraction emerged as another key resource, with underground mining commencing in 1906 when the Detroit Salt and Manufacturing Company began sinking a shaft to access Salina Formation deposits beneath the city, reaching production by 1910 after overcoming significant engineering challenges posed by overlying glacial drift.[67][68] The 1920s heralded a significant boom in basin exploitation, driven by key discoveries in carbonate reef structures that revealed the extent of trapped hydrocarbons. The Deerfield field in Monroe County, uncovered in 1920, produced from Trenton Formation reefs along a structural monocline, with five wells yielding oil initially.[55] This was followed by the Saginaw field's 1925 discovery in Saginaw County, where Berea Sandstone and underlying Niagaran reefs proved prolific, leading to over 300 wells drilled in the area by 1927 and transforming local economies.[69][55] The momentum accelerated with the Muskegon field's 1927 find in Traverse Limestone reefs, drawing speculators and resulting in hundreds more wells across the basin; by the late 1920s, cumulative drilling exceeded several thousand sites, though exact figures for 1925 remain around a few hundred active operations amid the rapid expansion.[66] These reef-related breakthroughs, often involving dolomitized pinnacles, underscored the basin's structural traps and fueled an era of wildcatting that laid the foundation for sustained resource development.[70]Modern Industry

The modern industry in the Michigan Basin centers on hydrocarbon extraction and salt mining, with operations leveraging advanced technologies like hydraulic fracturing to access previously uneconomical reserves. Annual crude oil production in Michigan, primarily from the basin, reached approximately 4.9 million barrels in 2023, accounting for a modest but steady contribution to state output.[71] Natural gas production totaled about 76 billion cubic feet in 2023, representing 0.2% of U.S. totals and reflecting a decline from historical peaks but stabilization through targeted drilling.[56] A notable revival in shale gas occurred since 2008, driven by hydraulic fracturing in formations like the Collingwood Shale, exemplified by Encana Corporation's acquisition of a 250,000-net-acre leasehold position starting that year, which spurred exploration and development in the northern basin.[72] Independent operators dominate hydrocarbon activities, focusing on conventional fields in the basin's Antrim Shale and deeper Niagaran reefs, supplemented by smaller-scale fracking operations that have enhanced recovery rates without large-scale corporate involvement. Salt production remains a cornerstone, with underground mines extracting rock salt from Silurian evaporites; the Detroit Salt Mine alone outputs approximately 2 million tons annually as of 2024, primarily for de-icing and industrial uses.[73] Other key facilities, such as the Manistee Mine operated by Morton Salt, contribute to Michigan's total salt output, which ranks among the nation's highest, supporting regional infrastructure needs.[74] The basin's resources generate significant economic value. As of 2015, the oil and natural gas sector contributed $13.6 billion in total economic output—equivalent to 3% of Michigan's GDP—and supported 22,781 direct jobs alongside 47,105 total positions including indirect and induced effects.[75] Since then, production has declined, but the sector continues to provide steady economic contributions through ongoing operations and exploration as of 2023. Salt mining adds to this, bolstering the mining sector's employment and output, though updated figures indicate sustained impacts into the 2020s through efficient underground extraction methods.[76] These activities build on historical foundations of resource development while adapting to contemporary market demands.Environmental Considerations

Subsidence and Land Stability

The Michigan Basin experiences natural subsidence primarily through post-glacial isostatic adjustment, where the collapse of the ancient glacial forebulge in southern regions leads to downward vertical motion at rates of approximately 1-2 mm per year.[77] This process results from the ongoing viscous relaxation of the Earth's mantle following the removal of ice sheet loads during the last glacial maximum, with GPS measurements confirming subsidence in Michigan after accounting for lake loading effects.[77] Although this natural adjustment contributes to long-term land stability concerns, its rates are minor compared to localized induced effects from human activities.[78] Induced subsidence in the basin poses significant hazards, mainly from the dissolution of salt layers by groundwater infiltration and solution mining operations. These processes create underground cavities that weaken overlying strata, leading to surface collapses and sinkholes up to several hundred feet (over 100 m) wide.[79] Documented incidents include multiple sinkhole formations in the 1970s at brine fields near Detroit, such as the 1971 collapses at the Grosse Ile site, where uncontrolled freshwater injection dissolved salt beds 340-400 m deep, resulting in rapid surface failures up to 135 m in diameter after years of cavity expansion.[79] The evaporite formations, like those in the Silurian Salina Group, are especially vulnerable to such dissolution due to their solubility in undersaturated water.[79] To mitigate risks and track ground movement, authorities employ advanced monitoring techniques including Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) from satellite data and Global Positioning System (GPS) stations, which provide millimeter-precision measurements of deformation.[78] InSAR analyses of Sentinel-1 imagery over Detroit from 2015-2021, validated by GNSS, have revealed average subsidence rates of about 1.7 mm per year across much of the urban area, with localized accelerations up to 1 cm per year near active mining and extraction sites due to cavity-induced instability.[78] These tools enable early detection of anomalous subsidence patterns, supporting infrastructure planning and hazard zoning in salt-prone regions.[78]Resource Extraction Impacts

Resource extraction activities in the Michigan Basin, particularly salt solution mining and oil and gas drilling, pose significant risks to groundwater quality through brine injection and potential methane migration. In salt mining operations, water is injected into underground salt formations to dissolve the mineral, producing highly saline brine that is then extracted and often reinjected or disposed of via deep injection wells to prevent surface discharge. While regulated injection wells are designed to protect aquifers, brine leakage from these wells can introduce high concentrations of salts, metals, and other contaminants into overlying freshwater aquifers, potentially degrading drinking water sources across the basin's extensive groundwater systems. For instance, proposed potash solution mining projects in Osceola County have raised concerns about the injection of millions of gallons of briny wastewater annually, which could lead to saltwater intrusion and reduced flows to regional streams and wetlands.[80][81][82] Oil and gas extraction in formations like the Antrim Shale further threatens groundwater, with hydraulic fracturing and well drilling risking methane migration into shallow aquifers used for drinking water. Studies indicate that faulty well casings or fracturing-induced pathways can allow thermogenic methane from deeper reservoirs to migrate upward, contaminating potable supplies; in the Michigan Basin, noble gas analyses of Antrim Shale production sites have identified similar migration mechanisms in shallow groundwater near active wells.[83][84][85] Although Michigan's vertical fracking operations in the Antrim differ from horizontal methods elsewhere, abandoned or poorly sealed wells exacerbate these risks, as evidenced by documented methane leaks into aquifers from legacy oil and gas sites statewide.[86][84][85] Ecosystems in the basin face disruption from the physical footprint of extraction infrastructure and associated spills. Well pads for Antrim Shale gas development fragment habitats in northern Michigan's forests and wetlands, clearing land for drilling rigs and access roads, which reduces biodiversity and alters wildlife corridors in sensitive areas near the Great Lakes. Salt mining generates mine tailings and brine waste that, when mismanaged, contribute to sediment loading and chemical runoff into local waterways; legacy solution mining sites have left metal-enriched sediments in nearby lakes, perpetuating toxicity in aquatic food webs. Since the 1980s, spills from oil and gas operations have impacted Great Lakes tributaries, such as the 1980 Enbridge leak in the Upper Peninsula that released oil into forested streams feeding Lake Michigan, harming fish populations and riparian habitats for decades.[87][88][89] The Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) has overseen resource extraction since the 1970s, enforcing environmental protections under the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (1994) and federal Safe Drinking Water Act amendments. Key regulations include the Underground Injection Control program (primed by 1980 EPA rules) for brine disposal and well integrity standards to minimize aquifer contamination from mining and drilling. In the 2020s, EGLE expanded groundwater monitoring through the Hydrologic Enhancement for Michigan (HEMI) initiative, a partnership with the U.S. Geological Survey to upgrade observation networks and assess pumping impacts on the basin's aquifers, enabling better oversight of extraction-related risks.[80][90][91]References

- https://wiki.seg.org/wiki/Michigan_basin