Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Southeast Michigan

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

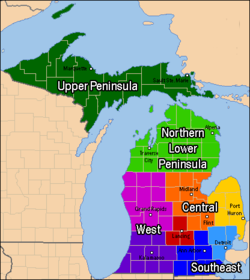

Southeast Michigan, also called southeastern Michigan, is a region in the Lower Peninsula of Michigan that is home to a majority of the state's businesses and industries as well as slightly over half of the state's population, most of whom are concentrated in Metro Detroit.

Geography

[edit]It is bordered in the northeast by Lake St. Clair, to the south-east Lake Erie, and the Detroit River which connects these two lakes.

Principal cities

[edit]- Detroit, the state's largest city (and the nation's eighteenth-largest) and the county seat of Wayne County.

- Mount Clemens, the county seat of Macomb County.

- Pontiac, the county seat of Oakland County.

Other important cities within the core counties of Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne

[edit]- Birmingham

- Dearborn

- Livonia

- Novi

- Romulus, home to Detroit Metro Airport

- Royal Oak

- Southfield

- Sterling Heights, the fourth-largest city (by population) in Michigan.

- Troy

- Warren, third-largest city (by population) in Michigan, location of General Motors Technical Center, the United States Army Tank-Automotive and Armaments Command (TACOM), the Tank Automotive Research, Development and Engineering Center (TARDEC), the National Automotive Center (NAC).

- West Bloomfield Township

Outlying cities

[edit]Some cities are considered within southeast Michigan, while also being a part of another region or metropolitan area. The following cities tend to identify themselves separately from southeast Michigan and are isolated from the core counties of Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne.

- Adrian, county seat of Lenawee County and home of Adrian College, Siena Heights University.

- Hillsdale, county seat of Hillsdale County located between the southeast and southwest corners of the state.

- Howell, county seat of Livingston County located between Metro Detroit and the Greater Lansing areas.

- Jackson, county seat of Jackson County also considered to be a part of Greater Lansing.

- Monroe, county seat of Monroe County.

- Port Huron, county seat of St. Clair County, also considered to be part of the Thumb.

- Saline, a community in Washtenaw County.

Metropolitan area

[edit]With 4,488,335 people in 2010, Metro Detroit was the tenth-largest metropolitan area in the United States, while Ann Arbor's metropolitan area ranked 141st with 341,847. Metropolitan areas of southeast Michigan, and parts of the Thumb and Flint/Tri-Cities, are grouped together by the U.S. Census Bureau with Detroit-Warren-Livonia MSA in a wider nine-county region designated the Detroit–Ann Arbor–Flint Combined Statistical Area (CSA) with a population of 5,428,000.

Combined Statistical Area

[edit]

- Genesee County

- Lapeer County

- Lenawee County (removed from the CSA in 2001 but relisted in 2013)

- Livingston County*

- Macomb County*

- Monroe County*

- Oakland County*

- Saint Clair County*

- Washtenaw County*

- Wayne County*

*Denotes member counties of the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG)

Economy

[edit]

The main economic activity is manufacturing cars. Major manufacturing cities are Warren, Sterling Heights, Dearborn (Henry Ford's childhood home) and Detroit, also called "Motor City" or "Motown". Other economic activities include banking and other service industries. Most people in Livingston, Macomb, Monroe, Oakland, Washtenaw, and Wayne Counties live in urban areas. In the recent years, urban sprawl has affected the areas of Canton, Commerce, Chesterfield, and Macomb townships. The metropolitan area is also home to some of the highest ranked hospitals and medical centers, Such as the Detroit Medical Center(DMC), Henry Ford Hospital, Beaumont Hospital, and the University of Michigan hospital in Ann Arbor.

SEMCOG Commuter Rail is a proposed regional rail link between Ann Arbor and Detroit.

The Detroit Metro Airport is the busiest in the area with the opening of the McNamara terminal and the now completed North Terminal. The airport is located in Romulus.

Manufacturing and service industries have replaced agriculture for the most part. In rural areas of Saint Clair County, Monroe, and Livingston Counties still grow crops such as corn, sugar beets, soy beans, other types of beans, and fruits. Romeo and northern Macomb County is well known for its apple and peach orchards.

Media

[edit]Most major Detroit radio stations, such as WJR and WWJ, can be heard in most or all of southeastern Michigan. Port Huron, Howell, Ann Arbor/Ypsilanti, Adrian, and Monroe are also served by their own locally-originating stations. National Public Radio is broadcast locally from Ann Arbor on Michigan Radio WUOM 91.7 FM and from Detroit on WDET-FM 101.9 FM.

Major television stations include: WJBK Fox 2 Detroit (Fox), WXYZ Channel 7 (ABC), WDIV Local 4 (NBC), WWJ-TV CBS 62 (CBS) and WKBD CW 50 (CW).

Newspaper

Daily editions of the Detroit Free Press and The Detroit News are available throughout the area.

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Ballard, Charles L. (2006). Michigan's Economic Future: Challenges and Opportunities. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-796-4.

- Ballard, Charles L., Paul N. Courant, and Douglas C. Drake (2003). Michigan at the Millennium. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87013-668-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cantor, George (2005). Detroit: An Insiders Guide to Michigan. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-03092-2.

- Fisher, Dale (2005). Southeast Michigan: Horizons of Growth. Grass Lake, MI: Eyry of the Eagle Publishing. ISBN 1-891143-25-5.

- Gavrilovich, Peter & Bill McGraw (2000). The Detroit Almanac. Detroit Free Press. ISBN 0-937247-34-0.

External links

[edit]- Clarke Historical Library, Central Michigan University, Bibliography on Michigan (arranged by counties and regions)

- Info Michigan, detailed information on 630 cities

- Michigan Department of Natural Resources website, harbors, hunting, resources and more.

- Michigan's Official Economic Development and Travel Site, including interactive map, information on attractions, museums, etc.

- Southeast Michigan Council of Governments

Southeast Michigan

View on GrokipediaGeography

Topography and Climate

Southeast Michigan features predominantly flat to gently rolling terrain shaped by Pleistocene glaciation, consisting of outwash plains, till plains, and end moraines from the Saginaw and Huron-Erie ice lobes.[12] The Maumee River plain underlies much of the Detroit area, providing low-relief landscapes suitable for urban and agricultural development.[13] Elevations generally range from 571 feet (174 meters) above sea level along the Lake Erie shoreline to 600–900 feet (183–274 meters) in inland counties like Genesee and Oakland, with subtle variations from glacial deposits rather than dramatic relief.[14][15] The region's landforms include scattered drumlins, eskers, and kettle lakes in southern areas, contributing to localized wetlands and small water bodies, while urban expansion in Wayne and Macomb counties has altered natural drainage patterns.[16] Proximity to Lakes Erie and Huron moderates microclimates but exposes the area to occasional flooding from the Detroit and St. Clair rivers.[17] Southeast Michigan experiences a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), characterized by cold, snowy winters and warm, humid summers, with significant moderation from the Great Lakes that reduces temperature extremes compared to inland Midwest areas.[16] In Detroit, average January temperatures feature highs of 32.3°F (0.2°C) and lows of 19.2°F (−7.1°C), while July highs reach 83°F (28°C) with lows around 66°F (19°C); annual average temperature is approximately 50°F (10°C).[18][19] Precipitation totals about 31 inches (787 mm) annually in Detroit, distributed fairly evenly but with peaks in spring and fall; lake-effect snow from Lakes Erie and Huron adds 30–40 inches (76–102 cm) of snowfall per winter, particularly affecting eastern counties like Macomb and St. Clair.[18][20] Since the early 20th century, temperatures have risen nearly 3°F (1.7°C), with increased precipitation trends of about 25% in the Detroit area, linked to broader regional warming.[21][22]Major Cities and Urban Centers

Detroit serves as the dominant urban center of Southeast Michigan, with a 2023 population of 636,644 that marked the first increase in decades, followed by a 1.1% rise in 2024 adding 6,791 residents, outpacing Michigan's statewide growth rate of 0.6%.[23][24] This reversal from long-term decline stems partly from policies attracting immigrants, bolstering the labor force amid ongoing revitalization in the automotive sector and emerging tech industries, though median household income remains at $39,575 with a poverty rate exceeding 30%.[25][26] Surrounding Detroit, the Metro Detroit suburbs host several significant urban centers, including Warren, the state's third-largest city with 137,686 residents as of recent estimates, and Sterling Heights, fourth-largest at 134,342, both characterized by manufacturing bases tied to automotive suppliers and a mix of residential and commercial development.[27] These inner-ring suburbs feature diverse populations, with Warren maintaining a strong Polish-American heritage alongside growing Chaldean and Arab communities, while Sterling Heights emphasizes parks, trails, and retail hubs supporting over 15 miles of recreational paths.[28][29] Ann Arbor, in adjacent Washtenaw County, stands as a distinct major urban center with a 2023 population of 121,179, driven economically by the University of Michigan, which enrolls over 52,000 students and generates substantial impact through education, research, and affiliated healthcare and tech sectors.[30][31] The university's presence fosters innovation but strains local housing and tax revenues due to its tax-exempt land holdings, prompting city adaptations like payments from student housing developments to offset fiscal losses.[32] Despite a slight population dip of 0.8% from 2022 to 2023, Ann Arbor's median household income of around $78,000 reflects its affluent, knowledge-based economy.[30]Core Counties and Outlying Areas

The core counties of Southeast Michigan—Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb—constitute the region's primary urban and suburban expanse, centered on the Detroit metropolitan area and characterized by high population density, extensive infrastructure, and industrial heritage along the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair. Wayne County, the most populous at approximately 1,735,623 residents in 2025 estimates, encompasses Detroit and its immediate environs, featuring flat glacial plains, urban waterways, and key transportation hubs like Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport.[33] Oakland County, with 1,269,228 residents, lies to the northwest and includes affluent suburbs amid gently rolling terrain, kettle lakes, and moraines formed by Pleistocene glaciation, supporting a mix of commercial districts and preserved natural areas like the Huron-Clinton Metroparks.[33] Macomb County, home to 876,833 people, extends northeastward with predominantly level farmland transitioning to suburban development, bordered by Lake St. Clair and marked by dredged channels for maritime access.[33] These core counties collectively span about 1,800 square miles of highly developed land, where urban sprawl has altered much of the original oak savanna and wetland ecosystems into highways, factories, and residential zones, though remnants of coastal marshes persist along water bodies.[34] Population densities exceed 1,000 persons per square mile in many municipalities, driven by historical automotive manufacturing that concentrated employment and housing.[35] Outlying areas, including Washtenaw, Livingston, Monroe, and St. Clair counties, serve as peripheral buffers with lower densities, agricultural lands, and emerging exurban growth, linking the core to broader southern Michigan. Washtenaw County, population around 365,000, features the Huron River valley and hilly uplands supporting Ann Arbor's university-driven economy amid forested ridges.[33] Livingston County, with about 195,000 residents, offers rural lakeshores and woodlots on the northern fringe, experiencing suburban encroachment from Oakland.[33] Monroe County, bordering Ohio along Lake Erie, maintains flat till plains for farming and wetlands, with 157,000 inhabitants focused on cross-border trade.[33] St. Clair County, population 163,000, hugs the St. Clair River and Lake Huron with sandy beaches and industrial ports at Port Huron, blending recreation and shipping.[33] These counties, totaling over 3,000 square miles, preserve more of the region's pre-settlement hydrology and biodiversity, including migratory bird habitats, while facing pressures from regional commuting patterns.[34]| County | Core/Outlying | Est. Population (2025) | Land Area (sq mi) | Key Geographic Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wayne | Core | 1,735,623 | 612 | Detroit River waterfront, urban plains[33] |

| Oakland | Core | 1,269,228 | 867 | Moraines, inland lakes[33] |

| Macomb | Core | 876,833 | 479 | Lake St. Clair marshes, flatlands[33] |

| Washtenaw | Outlying | ~365,000 | 709 | Huron River hills, forests[33] |

| Livingston | Outlying | ~195,000 | 565 | Kettle lakes, rural woodlands[33] |

| Monroe | Outlying | 157,000 | 598 | Lake Erie shores, wetlands[33] |

| St. Clair | Outlying | 163,000 | 724 | St. Clair River delta, beaches[33] |

History

Early Settlement and Indigenous Presence

The region of southeast Michigan, encompassing the Detroit River and surrounding waterways, was inhabited by indigenous peoples for millennia prior to European arrival, with archaeological evidence indicating human occupation dating back over 10,000 years through Paleo-Indian and Woodland period cultures.[36] By the time of sustained European contact in the 17th century, the area was primarily occupied by Anishinaabe nations forming the Council of Three Fires: the Ojibwe (also known as Chippewa), Ottawa (Odawa), and Potawatomi, who maintained villages, seasonal camps, and trade networks along the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair for hunting, fishing, and agriculture.[37] [38] The Wyandot (Huron), originally from the Ontario region, also had a presence in the southeastern Lower Peninsula, engaging in alliances and conflicts with neighboring tribes like the Iroquois.[39] These groups subsisted on maize cultivation, wild rice gathering, and exploitation of the abundant fur-bearing animals, with oral traditions and migration stories linking their origins to the Great Lakes region.[40] French explorers first ventured into the area in the late 17th century, drawn by the lucrative fur trade and strategic waterways connecting Lakes Erie and Huron. In 1679, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, passed through the Detroit River en route to Lake Michigan, noting indigenous villages but establishing no permanent post.[41] The pivotal European settlement occurred on July 24, 1701, when Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, under commission from King Louis XIV, led approximately 50 French soldiers, 50 colonists, and a contingent of about 100 allied Ottawa and Huron warriors to the site, founding Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit as a military outpost and trading hub to counter British expansion and secure French claims against Iroquois incursions.[42] [43] The fort, named after the French marine minister Jérôme Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain, consisted of wooden palisades enclosing barracks, a chapel, and storage, with an adjacent civilian settlement and indigenous encampment of allied tribes who provided support in exchange for trade goods like metal tools and firearms.[44] Early French-indigenous relations in the settlement were symbiotic yet tense, centered on the fur trade that exchanged beaver pelts for European manufactures, fostering temporary alliances but also introducing diseases and alcohol that decimated native populations. By 1710, the fort's population had grown to around 100 French inhabitants, bolstered by voyageurs and coureurs de bois, while nearby Potawatomi and Ottawa bands continued to dominate the regional landscape, using Detroit as a rendezvous point.[37] The settlement expanded modestly through the 1740s, with farms along the river supporting a mixed economy of agriculture and trade, though conflicts like the Fox Wars (1712–1733) disrupted alliances and led to temporary abandonments. Indigenous sovereignty persisted until the late 18th century, with tribes ceding specific lands via the 1807 Treaty of Detroit, signed by Ojibwe, Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Wyandot leaders, granting the U.S. government a six-mile square tract around Detroit in exchange for annuities and reserved hunting rights.[37] Further treaties in the 1830s, amid the Indian Removal Act of 1830, compelled most remaining Potawatomi and Ottawa from southeast Michigan westward, though pockets resisted full displacement through legal claims and reservations.[45]Industrialization and Automotive Rise (Late 19th to Mid-20th Century)

In the late 19th century, Southeast Michigan transitioned from agrarian and lumber-based economies to heavy industry, leveraging its strategic location on the Great Lakes for transportation and resource access. Detroit emerged as a manufacturing hub by the 1890s, benefiting from iron ore shipments from Michigan's Upper Peninsula and coal imports via lake vessels, which fueled steel production and machine shops. Industries such as shipbuilding, pharmaceuticals, and railway equipment proliferated, with twenty Detroit firms employing over 500 workers each by century's end, twelve in southwest Detroit alone. This foundation in metalworking and engineering, inherited from earlier carriage and stove manufacturing, positioned the region for mechanized innovation.[46][47] The automotive industry's ascent began in the 1890s with experimental self-propelled vehicles, culminating in commercial production around Detroit due to its skilled workforce and supply chains. Ransom E. Olds established Detroit's first automobile factory in 1899, producing the curved-dash Oldsmobile, while Henry Ford completed his first successful test drive in 1896 and incorporated Ford Motor Company in 1903. The Dodge brothers supplied engines and chassis components from their Detroit machine shop starting in 1902, supporting early firms. By 1908, William C. Durant founded General Motors in Flint, consolidating brands like Buick (established 1903 in Flint) and Oldsmobile. Southeast Michigan's auto cluster expanded rapidly, with three manufacturers and one supplier listed in Detroit's 1902 city directory, surging to 48 manufacturers and 100 suppliers by 1915.[48][49][50] Ford's introduction of the Model T in 1908 and the moving assembly line in 1913 at his Highland Park plant revolutionized production, reducing assembly time from 12 hours to 93 minutes per vehicle and enabling mass affordability. This innovation drove explosive growth: Detroit's population increased nearly sixfold from 1900 to 1930, reaching 1.57 million by 1930, fueled by immigrant and rural migrant labor attracted to auto jobs. The industry dominated the regional economy, employing hundreds of thousands by the 1920s and making Detroit the fourth-largest U.S. city by 1920. World War I demand for vehicles and parts further entrenched the sector, with factories converting to military production. Postwar, the Big Three—Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler (formed 1925 via merger)—solidified Southeast Michigan's preeminence, peaking at 296,000 manufacturing jobs and a metropolitan population approaching two million by 1950.[51][52][49]Postwar Expansion and Suburbanization

Following World War II, Southeast Michigan's economy surged due to the automotive sector's conversion from wartime to consumer production, driving population and territorial expansion. Manufacturing jobs in the region grew by 204,000, a 46 percent increase, from 1940 to 1970, attracting workers and their families.[53] This prosperity enabled widespread homeownership, with federal programs like the GI Bill providing low-interest mortgages that favored suburban single-family housing over urban rentals.[54] Suburban development accelerated as inexpensive farmland on the periphery of Detroit was converted into residential tracts, supported by the local auto industry's emphasis on automobile-dependent lifestyles. Key suburbs such as Livonia, incorporated in 1950 amid a housing boom, and Southfield emerged rapidly, with developers constructing thousands of ranch-style homes tailored to middle-class families seeking space and privacy.[55] The opening of Northland Center, the nation's first regional shopping mall, in Southfield in 1954, catalyzed commercial decentralization and further residential growth in Oakland County.[56] The expansion of the highway system underpinned this suburbanization by enabling efficient commutes from outlying areas to central factories. Construction of urban freeways in the Detroit area began in the late 1940s, with significant interstate projects like I-75 and I-94 advancing through the 1950s and 1960s under state and federal funding, increasing accessibility to peripheral land while displacing some inner-city residents.[57] By 1970, suburban counties had captured most net population gains, with the Detroit city's population declining from its 1950 peak of 1,849,568 as households relocated outward for perceived advantages in quality of life, including lower densities and newer infrastructure.[58] This pattern reflected broader national trends but was amplified in Southeast Michigan by the auto industry's wealth generation and land availability, though later analyses often emphasize discriminatory lending practices in explaining uneven racial distributions.[59]Decline, Deindustrialization, and Urban Crisis (1970s–2000s)

The automotive industry, the economic backbone of Southeast Michigan, faced profound challenges starting in the 1970s due to external shocks and structural inefficiencies. The 1973 oil embargo and subsequent 1979 energy crisis disproportionately affected Detroit's Big Three automakers—General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler—which dominated production of large, fuel-inefficient vehicles ill-suited to rising gasoline prices and shifting consumer preferences toward smaller imports.[60] These events triggered recessions that slashed auto sales, leading to widespread layoffs and plant idlings; Michigan's manufacturing employment share, heavily auto-dependent, fell from 36% of the workforce in 1970 to 23% by 2000.[61] Intensifying Japanese and German competition, fueled by superior fuel economy, reliability, and lower production costs, eroded U.S. market share from over 80% in 1970 to about 70% by 1980, prompting automakers to offshore assembly and suppliers to relocate southward for cheaper labor and non-union environments.[60] High union wages, rigid work rules, and legacy pension/healthcare obligations further strained competitiveness, with auto-related jobs in Michigan declining by over 200,000 from peak levels in the late 1970s through the 1980s recessions.[62] Deindustrialization accelerated urban decay in core cities like Detroit, as job losses cascaded into population exodus and infrastructure neglect. Detroit's population dropped from 1.51 million in 1970 to 1.20 million by 1980 and further to 951,000 in 2000, reflecting not only manufacturing flight but also middle-class suburbanization and out-migration driven by deteriorating city services and safety concerns. Southeast Michigan's suburbs, such as those in Oakland and Macomb counties, absorbed much of the outflow, with regional metro population stabilizing around 4.5 million by the 2000s, but exacerbating central city hollowing; abandoned factories and homes proliferated, as maintenance costs outstripped property values in blighted areas.[63] The 1980s and early 1990s recessions compounded this, with Chrysler requiring a $1.5 billion federal bailout in 1979-1980 and ongoing GM/Ford consolidations closing dozens of plants, including iconic facilities like Detroit's Poletown, razed in 1981 for a GM site that underperformed.[64] The urban crisis manifested in surging poverty, crime, and fiscal insolvency, trapping remaining residents in cycles of dependency. Poverty rates in Detroit climbed above 30% by the 1980s, with child poverty nearing 60% amid single-parent households and welfare reliance, as auto job losses eliminated stable blue-collar livelihoods.[65] Crime rates soared, with homicides peaking at over 700 annually in the early 1990s—among the highest per capita in the U.S.—fueled by unemployment, drug epidemics, and gang violence in depopulated neighborhoods.[66] Municipal governance faltered under mayors like Coleman Young (1974-1994), whose administration accrued billions in debt through excessive borrowing for operations rather than reforms, imposed new taxes without expenditure controls, and alienated suburban taxpayers via regional feuds, culminating in credit downgrades and service breakdowns by the 2000s.[64] While some analyses emphasize racial dynamics in flight patterns, empirical patterns align more closely with economic signaling: families prioritized safer, lower-tax suburbs with better schools, irrespective of demographics, as evidenced by parallel outflows from white ethnic enclaves.[63] This era's intertwined economic and social unraveling left Southeast Michigan's urban core a cautionary model of path-dependent decline from overreliance on a single industry.Bankruptcy, Restructuring, and Initial Recovery (2010s)

The City of Detroit filed for Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy on July 18, 2013, marking the largest such filing in U.S. history with estimated liabilities ranging from $18 billion to $20 billion, primarily consisting of pension obligations, health care benefits for retirees, and unsecured debt.[67][68] The filing followed years of structural deficits, exacerbated by population loss from 951,270 in 2000 to 713,777 by the 2010 census, shrinking tax bases, and operational inefficiencies in city services such as street lighting and police response times.[67] A federal bankruptcy judge ruled on December 3, 2013, that Detroit met Chapter 9 eligibility criteria, rejecting challenges from pension funds and other creditors who argued the city failed to negotiate in good faith.[67] Under emergency manager Kevyn Orr, appointed by Michigan Governor Rick Snyder earlier in 2013, the city pursued aggressive restructuring, including asset sales, service cuts, and negotiations with over 100,000 creditors.[69] The confirmed Plan of Adjustment in December 2014 reduced the city's long-term debt by about $7 billion, achieving this through creditor settlements that impaired unsecured bonds by up to 75% and restructured two underfunded pension systems: the General Retirement System and Police and Fire Retirement System.[69][70] Pensions faced cuts, including the elimination of non-guaranteed cost-of-living adjustments and an average 4.5% reduction for non-vested general retirees, despite Michigan's constitutional protections for benefits; the court determined pensions held no superior priority over other general unsecured claims.[69][71] The plan also allocated $816 million from state and philanthropic funds, including a $350 million "grand bargain" to protect the Detroit Institute of Arts collection from liquidation, averting potential losses for bondholders and pensioners.[69] Initial recovery efforts in the mid-to-late 2010s focused on fiscal stabilization and targeted revitalization, with the city achieving a balanced budget by fiscal year 2015 and restoring full bond market access by 2018 through improved credit ratings.[72] Private investments surged downtown, led by figures like Dan Gilbert, whose Quicken Loans expanded operations and acquired over 100 properties, catalyzing a commercial real estate boom with vacancy rates dropping to 5.9% by 2018.[73] Residential property values in Detroit doubled from 2012 levels by the early 2020s, though gains were uneven and concentrated in core neighborhoods, while broader challenges like persistent population decline—to 639,000 by 2020—limited spillover benefits to outer Southeast Michigan suburbs.[74] The bankruptcy's resolution indirectly aided the region by safeguarding the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, which serves three million customers across Southeast Michigan, preventing service disruptions from creditor claims on infrastructure revenue.[68] Metro Detroit's economy, encompassing Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties, showed broader recovery signs from the Great Recession by 2010, but Detroit's restructuring addressed city-specific liabilities without resolving regional deindustrialization drivers like automotive sector shifts.[67]Demographics

Population Size, Density, and Trends

Southeast Michigan, defined by the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG) as comprising Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, Washtenaw, Livingston, Monroe, and St. Clair counties, had a total population of 4,802,312 residents as of the latest available estimates.[1] This figure represents approximately 48% of Michigan's statewide population of about 10.08 million.[75] The core Detroit-Warren-Dearborn Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), excluding Washtenaw and Monroe counties, accounted for roughly 4.40 million people in 2024, reflecting a narrower but still dominant urban concentration.[76] Population density across the region averages 1.63 persons per acre, equivalent to approximately 1,043 persons per square mile, though this varies significantly by county due to urban-rural gradients.[1] Wayne County, home to Detroit, exhibits the highest density at 4.49 persons per acre (about 2,874 per square mile), driven by compact urban development, while outlying counties like Livingston and Monroe average below 1 person per acre (roughly 200-400 per square mile).[1] Oakland and Macomb counties, key suburban areas, maintain intermediate densities of around 1,400 and 1,000 persons per square mile, respectively, supporting residential sprawl and commercial nodes.[77] Historically, the region's population peaked in the mid-20th century amid automotive industrialization, reaching over 4.5 million in the MSA by 1950 before entering a prolonged decline through the 1970s-2000s due to manufacturing job losses and out-migration. From 2020 to 2023, the broader SEMCOG area experienced modest net changes, with gains in suburban counties offsetting urban losses, resulting in overall stability.[78] Recent estimates indicate a slight rebound, with the MSA population rising to 4.40 million in 2024 from 4.37 million in 2023, fueled by inner-ring suburban growth (up 0.73%) and early signs of Detroit city stabilization after decades of shrinkage.[76][79] Projections suggest continued slow growth through 2030, contingent on economic recovery and migration patterns, though outer suburbs show uneven expansion while core urban areas lag.| County | Population (Recent Est.) | Density (Persons/Sq. Mi.) |

|---|---|---|

| Wayne | 1,773,767 | ~2,874 |

| Oakland | 1,272,294 | ~1,400 |

| Macomb | ~870,000 | ~1,000 |

| Washtenaw | ~367,000 | ~500 |

| Others (Livingston, Monroe, St. Clair) | ~700,000 combined | 200-400 |

Racial, Ethnic, and Immigration Composition

The Detroit-Warren-Dearborn metropolitan statistical area, encompassing the core of Southeast Michigan with a 2020 population of 4,342,304, exhibits a racial composition of 66.3% White alone, 22.1% Black or African American alone, 3.3% Asian alone, 0.4% American Indian and Alaska Native alone, 0.02% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone, 3.1% some other race alone, and 4.8% two or more races.[81] Among these, non-Hispanic Whites constitute approximately 60%, reflecting historical patterns of white flight from Detroit to suburbs in Oakland and Macomb counties following the city's industrial peak. Detroit proper, with 633,221 residents in 2020, is 77.7% Black or African American alone, 10.2% White alone, and 8.0% Hispanic or Latino of any race, underscoring stark intra-regional segregation where the urban core remains predominantly Black while surrounding areas like Warren (86% White) and Troy (65% White, 20% Asian) are majority non-Hispanic White.[82] [23] Ethnically, European ancestries predominate among Whites, including significant Polish (over 200,000 in the metro area per ancestry surveys), German, Irish, and Italian heritage concentrated in Macomb and Wayne counties' blue-collar suburbs. Arab Americans form a notable ethnic cluster, numbering around 200,000 in the region—primarily Lebanese, Iraqi, and Yemeni in Dearborn and Hamtramck—making Southeast Michigan home to the largest Arab-American population outside the Middle East, driven by post-1970s refugee inflows. Hispanics, about 5.1% of the MSA (roughly 220,000), are largely Mexican-origin in Downriver areas and Southwest Detroit, with smaller Puerto Rican and Central American groups. Asians, 3.3% regionally, cluster in affluent suburbs like Troy and Canton, featuring Indian, Chinese, and Korean professionals tied to automotive engineering and tech sectors in Oakland and Washtenaw counties.[83] The foreign-born population in the Detroit metro area stood at approximately 8% in recent American Community Survey estimates (around 350,000 individuals), below the national average of 13.8%, with growth of 30% from 2010 to 2023 attributed to refugee resettlement and skilled migration. Leading countries of origin include Iraq (tens of thousands, concentrated in Wayne County due to post-2003 war displacement), India (professional visas in tech hubs), Mexico (labor migration), Lebanon (historical chains from the 1970s civil war), and China (academic ties to University of Michigan in Ann Arbor). This composition has bolstered population stability amid native out-migration, with immigrants accounting for over half of the metro's net growth in the 2010s; however, integration challenges persist in enclaves like Hamtramck, where Bangladeshi and Bosnian Muslims have shifted local politics.[84] [85] [86]| Racial/Ethnic Group | Percentage (2020 Census, Detroit MSA) | Approximate Population |

|---|---|---|

| White alone | 66.3% | 2,881,000 |

| Black/African American alone | 22.1% | 961,000 |

| Asian alone | 3.3% | 143,000 |

| Hispanic/Latino (any race) | 5.1% | 220,000 |

| Two or more races | 4.8% | 208,000 |

Age, Income, and Household Characteristics

The median age in the Detroit-Warren-Dearborn metropolitan statistical area (MSA), encompassing core Southeast Michigan counties, stood at 40.2 years in 2023, slightly above the national median of 39.2 years.[83][3] Approximately 21.3% of the population was under 18 years old, with the largest age cohorts comprising 12-13% each in the 20-29, 30-39, and 50-59 ranges, reflecting a balanced but aging demographic structure influenced by postwar baby boomer retirement and slower youth population growth amid economic shifts.[87][3] Median household income in the Detroit MSA reached $75,123 in 2023, up from $72,456 the prior year, though this lagged the U.S. median of $77,719, attributable to persistent deindustrialization effects and uneven recovery in urban cores versus suburbs.[83][3] Per capita personal income, as measured by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, was $66,098, reflecting contributions from automotive and related sectors but tempered by higher unemployment legacies in inner-city areas.[88] Income distribution showed 35% of households earning under $50,000 annually, with 26% above $100,000, indicating moderate inequality compared to national figures.[3] Average household size in Southeast Michigan averaged 2.48 persons in recent estimates, lower than the state average of 2.43 and national trends, driven by smaller family units and rising single-person households amid suburbanization and delayed family formation.[89] Over 1.9 million households existed region-wide, with family households comprising the majority but non-family units increasing due to aging populations and economic mobility constraints.[1] Poverty rates hovered around Michigan's 13.5% in 2023, with regional disparities evident: higher in urban Detroit proper (exceeding 30% in some tracts) versus suburban counties, linked to racial composition and job access rather than policy alone.[90][91]Economy

Key Industries and Economic Clusters

Southeast Michigan's economy is anchored by the automotive and mobility cluster, which originated in the early 20th century and remains the region's defining economic driver due to its scale, innovation in vehicle production, and integrated supply chain. The Detroit-Warren-Dearborn metropolitan statistical area (MSA) hosts the U.S. headquarters of General Motors, Ford Motor Company, and Stellantis, alongside assembly plants and engineering facilities that support global operations. Michigan accommodates operations from 96 of the world's top 100 automotive suppliers, fostering a dense ecosystem of parts manufacturing, R&D, and advanced technologies like electric vehicles and autonomous systems. In 2023, manufacturing employment—predominantly automotive—totaled 255,400 jobs in the MSA, comprising roughly 12% of total nonfarm payrolls amid a workforce of about 2.08 million.[92] [93] [94] Healthcare and life sciences form another core cluster, leveraging proximity to research universities and major hospital systems for medical innovation, patient care, and biomedical R&D. Institutions such as the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor and Henry Ford Health in Detroit employ tens of thousands and drive advancements in areas like genomics and personalized medicine, with the sector ranking among the largest employers due to an aging population and specialized facilities. Education and health services account for a significant share of employment, exceeding 20% in urban cores like Detroit, supported by federal funding and private investment that have sustained growth even during manufacturing downturns.[95] [96] Logistics, transportation, and distribution benefit from the region's central Great Lakes position, with four Class I railroads, Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport handling over 35 million passengers annually pre-pandemic, and the busiest U.S.-Canada commercial border crossing facilitating $130 billion in annual trade. This cluster enables just-in-time supply chains critical to automotive production and e-commerce, employing workers in warehousing, freight, and cross-border operations. Defense and advanced manufacturing clusters, particularly in Macomb County's Defense Corridor, contribute through aerospace R&D, testing facilities, and contracts from the U.S. military, including the Detroit Arsenal, which bolsters metalworking and engineering expertise transferable to civilian sectors.[97] [98] Emerging clusters in information technology, financial services, and research-engineering-design (RED) are gaining traction, fueled by talent from universities like the University of Michigan and initiatives to diversify beyond legacy industries. IT hubs in Ann Arbor and Troy support software for mobility and cybersecurity, while financial firms cluster in downtown Detroit for asset management tied to industrial finance. These sectors, though smaller, exhibit higher growth rates, with RED encompassing design firms and tech centers that complement automotive innovation without the volatility of traditional manufacturing cycles. The overall regional GDP stood at $290 billion in 2021, with manufacturing and trade-related activities forming the largest contributions amid efforts to integrate electric vehicle transitions and digital economies.[99] [100] [101]Workforce Participation and Employment Patterns

In Southeast Michigan, the labor force participation rate remained unchanged in 2024, tracking closely with Michigan's statewide average of 61.8 percent for the year.[102][103] Between 2022 and 2023, the region's total employed population expanded by 67,000 individuals, slightly exceeding labor force growth of 64,000 and supporting a tighter job market.[104] As of August 2025, the area's unemployment rate stood at 4.4 percent, below the state figure of 5.2 percent and reflecting stronger local demand relative to broader Michigan trends.[105][106] Employment patterns in the region have shifted from heavy reliance on manufacturing—historically dominated by the automotive sector—toward services, health care, and professional occupations, though vehicle production retains outsized influence via major employers such as Ford Motor Company, General Motors, and Stellantis, which together support over 164,000 jobs.[107] In 2024, job gains were concentrated in natural resources, mining, and construction; private education and health services; and government, with health care emerging as the largest sector, employing over 400,000 workers by projections extending into the mid-2030s.[108][109] Sectoral shares in the broader Detroit region include trade, transportation, and utilities at 19 percent; professional and business services at 17 percent; and health services with private education at 16 percent, underscoring diversification amid manufacturing's contraction from deindustrialization pressures since the 1970s.[107] These patterns exhibit resilience post-2013 Detroit bankruptcy, with sustained growth in advanced manufacturing, mobility technologies, and engineering clusters, though participation lags national averages due to structural factors like skill mismatches and demographic aging in former auto-dependent communities.[110] Commuting data reveal a regional laborshed where workers increasingly flow from suburban and exurban areas into urban cores for services and logistics roles, amplifying patterns of spatial mismatch in access to high-wage manufacturing jobs.[111] Overall, employment remains cyclically sensitive to automotive output, with recent expansions tied to electric vehicle transitions rather than volume recovery alone.[112]Business Environment and Innovation Hubs

Southeast Michigan's business environment benefits from Michigan's overall strong state rankings, including sixth place in CNBC's 2025 Top States for Business assessment, driven by factors such as infrastructure and workforce quality.[113] The region also contributes to the state's top-10 business climate ranking by Site Selection Magazine in November 2024, supported by initiatives like the "Make It in Michigan" strategy emphasizing people, places, and projects for economic growth.[114] [115] However, a 2025 study notes Southeast Michigan's economy remains resilient yet lags behind peer regions in key metrics like productivity and innovation output, amid challenges from labor shortages and slower diversification beyond manufacturing.[116] New business applications in Michigan rose 28 percent in 2024 compared to 2019 levels, indicating entrepreneurial momentum despite vulnerabilities to automotive sector fluctuations.[117] Innovation hubs in Southeast Michigan center on collaborative ecosystems linking universities, startups, and industry, with Ann Arbor emerging as a leading tech node through Michigan SmartZones that foster public-private partnerships for entrepreneurship.[118] The Ann Arbor region hosts concentrations in information technology and high-tech services, ranking it ahead of Detroit as the top Midwest city for startups in a 2025 assessment.[119] [120] In Detroit, the University of Michigan Center for Innovation supports research, education, and job creation in advanced technologies, complementing local projects aimed at transforming the entrepreneurial landscape.[121] Proposals for a Detroit-Ann Arbor Innovation Corridor seek to integrate these assets, competing with national hubs by leveraging combined venture capital inflows of $452 million in Detroit and $359 million in Ann Arbor as reported in recent PitchBook data.[122] [123] State initiatives, including the first Venture Michigan Fund allocations in over a decade, provided millions in 2025 to support startups, with Ann Arbor SPARK facilitating 23 investments via a $5 million grant.[124] [125]Government and Politics

Local and Regional Governance

Southeast Michigan's local governance operates within Michigan's decentralized framework, featuring 83 counties statewide, with the region primarily encompassing seven: Livingston, Macomb, Monroe, Oakland, St. Clair, Washtenaw, and Wayne.[34] Each county is governed by an elected board of commissioners, which oversees functions such as public health, jails, courts, elections, and road maintenance, though authority varies by county charter or state law.[126] This structure reflects Michigan's emphasis on local autonomy, resulting in overlapping jurisdictions among counties, cities, townships, and villages, which can complicate regional coordination on issues like land use and services.[127] Municipalities within these counties include 280 cities and 253 villages statewide, many operating under home rule charters that grant broad powers for self-governance, including taxation and zoning.[128] Detroit, the region's core city and Wayne County's seat, employs a strong mayor-council system where the mayor serves as chief executive with control over administrative departments and veto authority, while the nine-member city council handles legislation, including a president and seven district representatives plus two at-large members.[129] [130] Surrounding areas feature numerous charter townships and general law townships, the latter predominant in southeastern Michigan with 72 such units as of 2015, each led by an elected supervisor, clerk, treasurer, and board of trustees under state statutes rather than local charters.[131] Regional governance addresses fragmentation through voluntary associations like the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG), established as a planning partnership for the seven counties and serving 4.8 million residents across 185 member communities.[132] SEMCOG facilitates data-driven collaboration on transportation infrastructure, environmental protection, and economic development, providing technical assistance and advocating for federal funding without direct regulatory authority.[133] Michigan law enables such councils and limited-purpose regional authorities for specific functions, but the absence of a consolidated metropolitan government underscores reliance on interlocal agreements to mitigate service duplication and fiscal inefficiencies inherent in the state's 2,877 local units.[134][135]Electoral History and Political Affiliations

Southeast Michigan's electoral landscape reflects its industrial roots and demographic diversity, with urban centers like Detroit in Wayne County forming a reliable Democratic base influenced by unionized labor, particularly the United Auto Workers (UAW), which has historically mobilized voters toward Democratic candidates since the New Deal era.[136] Suburban counties such as Oakland and Macomb exhibit greater volatility, with working-class voters in Macomb—known as "Reagan Democrats"—shifting toward Republican nominees in response to economic concerns and cultural issues, as seen in their support for Ronald Reagan in 1980 (Reagan won Macomb with 58% amid national union discontent following the air traffic controllers' strike) and Donald Trump in 2016.[137][138] This pattern underscores causal factors like deindustrialization and wage stagnation, which eroded traditional party loyalties without evidence of coordinated media-driven shifts, contrasting with claims of uniform partisan realignment. In presidential elections from 2000 to 2024, Wayne and Washtenaw counties delivered overwhelming Democratic victories, while Macomb and Monroe leaned Republican in key cycles, contributing to Michigan's swing-state status. For instance, in 2016, Trump secured Macomb County by 11 points (53.6% to 41.7%) and Monroe by 15 points (56.1% to 38.6%), flipping the state, but lost Wayne (64.5% to 31.3%) and Washtenaw (71.0% to 23.9%).[139] Biden reversed the state outcome in 2020, winning Oakland (56.1% to 42.2%) and holding Wayne (68.3% to 30.0%) and Washtenaw (72.0% to 26.0%), though Trump retained Macomb (53.0% to 45.4%) and Monroe (57.2% to 41.0%).[140] Trump recaptured Michigan in 2024 with 49.7% statewide, improving in Oakland suburbs while dominating Macomb (56% to Harris's 42%) and maintaining strong margins in Monroe, though Wayne remained heavily Democratic (Detroit proper gave Harris over 90% in precincts).[141][142]| Year | Wayne County (Dem % / GOP %) | Oakland County (Dem % / GOP %) | Macomb County (Dem % / GOP %) | Washtenaw County (Dem % / GOP %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Gore 71 / Bush 27 | Gore 53 / Bush 44 | Gore 48 / Bush 50 | Gore 65 / Bush 31 |

| 2004 | Kerry 67 / Bush 32 | Kerry 52 / Bush 47 | Kerry 46 / Bush 53 | Kerry 65 / Bush 33 |

| 2008 | Obama 73 / McCain 26 | Obama 58 / McCain 40 | Obama 52 / McCain 46 | Obama 72 / McCain 26 |

| 2012 | Obama 73 / Romney 26 | Obama 57 / Romney 41 | Obama 50 / Romney 49 | Obama 72 / Romney 26 |

| 2016 | Clinton 65 / Trump 31 | Clinton 53 / Trump 44 | Clinton 42 / Trump 54 | Clinton 71 / Trump 24 |

| 2020 | Biden 68 / Trump 30 | Biden 56 / Trump 42 | Biden 45 / Trump 53 | Biden 72 / Trump 26 |

| 2024 | Harris ~65 / Trump ~33 | Harris ~50 / Trump ~48 | Harris 42 / Trump 56 | Harris ~70 / Trump ~28 |