Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

SD card

View on Wikipedia

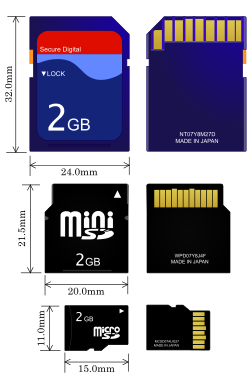

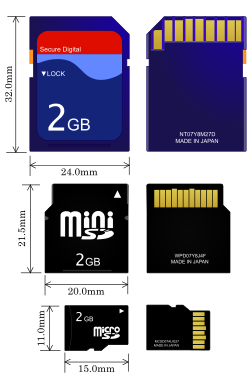

From top to bottom: SD, miniSD, microSD | |

| Media type | Memory card |

|---|---|

| Capacity |

|

| Block size | Variable |

| Read mechanism |

|

| Developed by | SD Association |

| Dimensions |

|

| Weight |

|

| Extended from | MultiMediaCard |

| Released | August 1999 |

The SD card is a proprietary, non-volatile, flash memory card format developed by the SD Association (SDA). They come in three physical forms: the full-size SD, the smaller miniSD (now obsolete), and the smallest, microSD. Owing to their compact form factor, SD cards have been widely adopted in a variety of portable consumer electronics, including digital cameras, camcorders, video game consoles, mobile phones, action cameras, and camera drones.[1][2]

The format was introduced in August 1999 as Secure Digital by SanDisk, Panasonic (then known as Matsushita), and Kioxia (then part of Toshiba). It was designed as a successor to the MultiMediaCard (MMC) format, introducing several enhancements including a digital rights management (DRM) feature, a more durable physical casing, and a mechanical write-protect switch. These improvements, combined with strong industry support, contributed to its widespread adoption.

To manage licensing and intellectual property rights, the founding companies established SD-3C, LLC. In January 2000, they also formed the SD Association, a non-profit organization responsible for developing the SD specifications and promoting the format.[3] As of 2023, the SDA includes approximately 1,000 member companies. The association uses trademarked logos owned by SD-3C to enforce compliance with official standards and to indicate product compatibility.[4]

History

[edit]Origins and standardization

[edit]In 1994, SanDisk introduced the CompactFlash (CF) format, one of the first successful flash memory card types.[5] CF outpaced several competing early formats, including the Miniature Card and SmartMedia. However, the late 1990s saw a proliferation of proprietary formats such as Sony's Memory Stick and the xD-Picture Card from Olympus and Fujifilm, resulting in a fragmented memory card market.[5]

To address these challenges, SanDisk partnered with Siemens and Nokia in 1996 to develop a new postage stamp-sized memory card called the MultiMediaCard (MMC). While technically innovative, MMC adoption was slow, and even Nokia was slow to integrate support for it into its mobile devices.[5]

In 1999, SanDisk was approached by Panasonic (then known as Matsushita) and Kioxia (then part of Toshiba) to develop a new format as a second-generation successor to MMC.[6] The goal was to create a portable, high-performance memory card with integrated security features and broader interoperability. Concerned about losing market share to Sony's proprietary Memory Stick, Toshiba and Panasonic saw the collaboration as an opportunity to establish an open, industry-backed standard.[5][7]

Panasonic and Toshiba, who had previously collaborated on the Super Density Disc (a DVD precursor), reused its stylized "SD" logo for the Secure Digital (SD) card format.[8] Anticipating the growth of MP3 players, they also advocated for digital rights management (DRM) support seeking to reassure content publishers wary of piracy.[5][9] The DRM system adopted—Content Protection for Recordable Media (CPRM)—had been developed earlier in partnership with IBM and Intel, and Intel and complied with the Secure Digital Music Initiative standard.[10] Although often cited as a factor in the format's broad industry support, CPRM was rarely implemented in practice.[11][12] SD cards also featured a mechanical write-protect switch, and early SD slots maintained backward compatibility with MMC cards.[13]In early 2000, the first commercial SD cards offering 8 megabyte (MB)[a] of storage were released,[14] with larger capacity versions following shortly after. By August 2000, 64 MB cards were being sold for approximately US$200 (equivalent to $365 in 2024).[15] According to SanDisk, consumer adoption was accelerated by Toshiba and Panasonic's commitment to launching compatible devices in parallel with the cards.[5]

To support standardization and interoperability, SanDisk, Toshiba, and Panasonic announced the creation of the SD Association (SDA) at the January 2000 Consumer Electronics Show (CES). Headquartered in San Ramon, California, the SDA initially included 30 member companies and has since grown to encompass around 800 organizations worldwide.[16]

Smaller formats

[edit]

At the March 2003 CeBIT trade show, SanDisk introduced and demonstrated the miniSD card format.[17] The SD Association (SDA) adopted miniSD later that year as a small-form-factor extension to the SD card standard, intended primarily for use in mobile phones. However, the format was largely phased out by 2008 following the introduction of the even smaller microSD card.[18]

The microSD format was introduced by SanDisk at CeBIT in 2004,[19] initially under the name T-Flash,[20] later rebranded as TransFlash or TF. In 2005, the SDA adopted the format under the official name microSD,[21][22] though the TransFlash name remains in common use as a generic term for microSD cards.[23] A passive adapter allows microSD cards to be used in standard SD card slots, maintaining backward compatibility across devices.

Increasing storage density

[edit]

The storage capacity of SD cards increased steadily throughout the 2010s, driven by advances in NAND flash manufacturing and interface speeds. In January 2009, the SDA introduced the Secure Digital eXtended Capacity (SDXC) format, supporting up to 2 TB of storage and transfer speeds up to 300 MB/s.[24] SDXC cards are formatted with the exFAT file system by default.[25]

The first SDXC cards appeared in 2010, with early models offering capacities of 32 to 64 GB and read/write speeds of several hundred megabits per second.[26] Consumer adoption accelerated as digital cameras, smartphones, and card readers gained SDXC compatibility.

By 2011, manufacturers offered SDXC cards in 64 and 128 GB capacities, with some models supporting UHS Speed Class 10 and faster.[27] In the following years, capacity milestones were reached at regular intervals: 256 GB in 2013, 512 GB in 2014, and 1 TB in 2019.[28]

The Secure Digital Ultra Capacity (SDUC) specification, announced in 2018, expanded maximum capacity to 128 TB and increased theoretical transfer speeds to 985 MB/s.[29] In 2022, Kioxia previewed the first 2 TB microSDXC card,[30] and in 2024, Western Digital announced the first 4 TB SDUC card, scheduled for commercial release in 2025.[31]

Capacity standards

[edit]There are four defined SD capacity standards: Standard Capacity (SDSC), High Capacity (SDHC), Extended Capacity (SDXC), and Ultra Capacity (SDUC). In addition to specifying maximum storage limits, these standards also define preferred file systems for formatting cards.[25][32][33]

| SDSC | SDHC | SDXC | SDUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mark | ||||

| Max capacity | 2 GB | 32 GB | 2 TB | 128 TB |

| File system | FAT12, FAT16 | FAT32 | exFAT | |

SD (SDSC)

[edit]The original Secure Digital (SD) card was introduced in 1999 as a successor to the MMC format. The name SD Standard Capacity (SDSC) was applied later to distinguish it from newer variants. Although based on the same electrical interface as MMC, the SD format introduced several enhancements aimed at improving usability, durability, and performance:

- A notched, asymmetrical shape to prevent incorrect insertion.[34]: 27–28

- Recessed electrical contacts to protect against damage and contamination.

- A four-line data bus for faster transfers, compared to MMC's single data line.[34]: 17

- A mechanical write-protect switch.[34]: 27

- These features came at the expense of increased card thickness: 2.1 mm (0.083 in) for standard SD cards, compared to 1.4 mm (0.055 in) for MMC. A 1.4 mm Thin SD variant was also defined,[34] but saw little use.

SDSC cards support capacities up to 2 GB[b] and use the FAT12 or FAT16 file system. They remain compatible with most SD-capable devices but have been largely superseded by higher-capacity formats.

Because of physical differences, full-size SD cards do not fit in slim MMC-only slots.

SDHC

[edit]SD High Capacity (SDHC) was introduced in SD specification version 2.0, released in January 2006.[35] It expands the maximum capacity to 32 GB, compared to the 2 GB limit of SDSC.[b][25]

SDHC cards are physically identical to earlier standard-capacity SD (SDSC) cards, but differ in how they store and address data. This includes a redefinition of the Card-Specific Data (CSD) register (for details, see § Storage capacity calculations). Additionally, SDHC cards are typically preformatted with the FAT32 file system.

SDHC-compatible devices are required to support older SDSC cards. However, older SDSC devices may not recognize SDHC cards without a firmware update.[36] Older operating systems like Windows XP require patches or service packs to access SDHC cards.[37][38][39]

SDXC

[edit]SD eXtended Capacity (SDXC) was introduced in SD specification version 3.01, released in January 2009.[40] It expands the maximum capacity to 2 TB,[c] compared to the 32 GB[b] limit of SDHC. SDXC cards are formatted with the exFAT file system, which is required by the SDXC standard.[41][25] While Windows Vista SP1 and later and Mac OS X 10.6.5 and later support exFAT natively,[42][43][44] support in BSD and Linux distributions was limited until Microsoft released the exFAT specification and Linux kernel 5.4 included an open-source driver.[45]

SDXC cards can be reformatted to other file systems (e.g., ext4, UFS, VFAT or NTFS), which may improve compatibility with older devices or systems lacking exFAT support. Many SDHC-compatible hosts can use SDXC cards if reformatted to FAT32, but full compatibility is not guaranteed.[46][47][48]

SDUC

[edit]SD Ultra Capacity (SDUC) was introduced in SD specification version 7.0, released in June 2018. It expands the maximum capacity to 128 TB,[c] compared to the 2 TB limit of SDXC.[49] Like SDXC cards, SDUC cards use the exFAT file system by default.

Bus marks

[edit]Bus marks indicate both the bus interface and the minimum data transfer performance of a device (as opposed to speed class ratings which indicate card performance) in terms of sustained sequential read and write speeds. These are most relevant for handling large files—such as photos and videos—where data is accessed in contiguous blocks. The SD specification has improved bus speed performance over time by increasing the clock frequency used to transfer data between the card and the host device. Regardless of the bus speed, a card may signal that it is "busy" while completing a read or write operation. Compliance with higher-speed bus standards typically reduces reliance on this "busy" signal, allowing for more efficient and continuous data transfers.

| Interface | Mark | Bus | Capacity standard | Spec | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | PCIe | Duplex | SD | SDHC | SDXC | SDUC | |||

| Default | — | 12.5 MB/s | — | Half | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1.01 |

| High Speed | — | 25 MB/s | Half | 1.10 | |||||

| UHS-I | 50 MB/s | Half | No | 3.01 | |||||

| 104 MB/s | |||||||||

| UHS-II | 156 MB/s | Full | 4.00, 4.10 | ||||||

| 312 MB/s | Half | ||||||||

| UHS-III | 312 MB/s | Full | 6.00 | ||||||

| 624 MB/s | |||||||||

| SD Express | 985 MB/s | 3.1 ×1 | — | 7.00, 7.10 | |||||

| 1,969 MB/s | 3.1 ×2, 4.0 ×1 | 8.0 | |||||||

| 3,938 MB/s | 4.0 ×2 | ||||||||

Host Card

|

UHS-I | UHS-II | UHS-III | Express | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UHS50 | UHS104 | Full | Half | ||||

| UHS-I | UHS50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| UHS104 | 50 | 104 | 104 | 104 | 104 | 104 | |

| UHS-II | Full | 50 | 104 | 156 | 156 | 156 | 156 |

| Half | 50 | 104 | 156 | 312 | 312 | 312 | |

| UHS-III | 50 | 104 | 156 | 312 | 624 | 624 | |

| Express | 50 | 104 | 104 | 104 | 104 | 3,938 | |

Default Speed

[edit]The original SD bus interface, introduced with version 1.00 of the SD specification, supported a maximum transfer rate of 12.5 MB/s. This mode is referred to as Default Speed.

High Speed

[edit]With version 1.10 of the specification, the SD Association introduced High-Speed mode, which increased the maximum transfer rate to 25 MB/s. This enhancement was designed to meet the growing performance requirements of devices such as digital cameras.[51]

UHS (Ultra High Speed)

[edit]The Ultra High Speed (UHS) bus interface enables faster data transfer on SDHC, SDXC and SDUC cards.[51][52]

UHS-compatible cards are marked with Roman numerals next to the SD logo, indicating the version of the UHS standard, and therefore the bus speeds, they support.[51][53] These cards offer significantly faster read and write speeds than earlier SD card types, making them well suited for high-resolution video, burst photography, and other data-intensive applications.

To achieve higher transfer speeds, UHS cards and devices use specialized electrical signaling and hardware interfaces. UHS-I cards operate at 1.8 V instead of the standard 3.3 V and use a four-bit transfer mode. UHS-II and UHS-III introduce a second row of interface pins to add a second lane of data transfer and use low-voltage differential signaling (LVDS) at 0.4 V to increase speed and reduce power consumption and electromagnetic interference (EMI).[54][50]

The following UHS speed classes are defined:

UHS-I

[edit]Support for the UHS-I interface was introduced in SD specification version 3.01, released in May 2010. This version added several new transfer modes: SDR50, which uses a 100 MHz clock with single data rate signaling to reach up to 50 MB/s; DDR50, a double data rate mode at 50 MHz that transfers data on both clock edges for up to 50 MB/s; and SDR104, which increases the clock speed to 208 MHz, enabling transfer rates up to 104 MB/s.[40]

In 2018, SanDisk developed a proprietary mode unofficially known as DDR200, which combines double data rate signaling with a 208 MHz clock to achieve read speeds of up to 170 MB/s without requiring additional pins. Write speeds remain limited to 104 MB/s, similar to SDR104. These higher speeds are typically used when offloading data from cards via specialized readers.[55][56] In 2022, SanDisk introduced DDR225, further increasing performance to up to 200 MB/s read and 140 MB/s write. Although neither mode is officially part of the SD specification, although they have been adopted by several other manufacturers.[57][58]

UHS-II

[edit]

Support for the UHS-II interface was introduced in SD specification version 4.0, released in January 2011. It added two new transfer modes: FD156, supporting up to 156 MB/s full-duplex, and HD312, enabling up to 312 MB/s half-duplex. These speeds required a second row of connectors for LVDS, bringing the total to 17 for full-size cards and 16 for microSD cards.[51][59]

Each LVDS lane can transfer up to 156 MB/s. In full-duplex mode, one lane is used for sending data and the other for receiving. In half-duplex mode, both lanes operate in the same direction.

While initial adoption began in cameras around 2014, wider implementation took several more years, as few applications required the extra speed provided by the interface.[60] As of 2025[update], only about 100 cameras, mostly high-end models, support UHS-II cards.[61]

UHS-III

[edit]Support for the UHS-III interface was introduced in SD specification version 6.0, released in February 2017. It added two new full-duplex transfer modes: FD312, offering up to 312 MB/s, and FD624, doubling that to 624 MB/s.[62] UHS-III retains the same physical interface and pin layout as UHS-II for backward compatibility.[63] However, as of 2025[update], UHS-III has seen limited adoption and is unlikely to be widely implemented, as the SDA instead prioritizes SD Express, which offers even higher transfer rates but limits backward compatibility to UHS-I speeds.[64][65]

SD Express

[edit]

SD Express was introduced in SD specification version 7.0, released in June 2018. By incorporating a single PCI Express 3.0 (PCIe) lane and supporting the NVM Express (NVMe) storage protocol, SD Express enables full-duplex transfer speeds of up to 985 MB/s. SD Express cards support direct memory access (DMA), which can improve performance, though security researchers have warned that it may also increase the attack surface in the event of a compromised or malicious card.[66] Compatible cards must support both PCIe and NVMe, and may be formatted as SDHC, SDXC, or SDUC. For backward compatibility, SD Express cards are also required to support the High-Speed and UHS-I bus interfaces. However, because the PCIe interface reuses the second row of pins previously used by UHS-II and UHS-III, compatibility with older devices is limited to UHS-I speeds. The specification also reserves space for two additional pins for future use.[67]

In February 2019, the SD Association introduced microSD Express,[68] along with updated visual marks to help users identify compatible cards and devices.[69]

SD specification version 8.0, released in May 2020, expanded the interface to support PCIe 4.0 and introduced dual-lane configurations for full-size cards by adding a third row of electrical contacts, bringing the total to 26. This raised the theoretical maximum transfer rate to 3,938 MB/s using dual-lane PCIe 4.0.[70] Due to space constraints, the microSD form factor cannot accommodate a third row of contacts and remains limited to a single PCIe lane.

Adoption has been gradual. In February 2024, Samsung began sampling its first microSD Express cards,[71] though commercial availability remained limited. Interest grew in April 2025 when Nintendo announced that the Switch 2 would support only microSD Express cards, with UHS-I card support limited to transferring media from earlier models.[72]

As of June 2025[update], only single-lane PCIe 3.1 SD Express cards are commercially available; no PCIe 4.0 or dual-lane cards have been released for general sale.[60][73]

Card speed class ratings

[edit]| Min speed | Speed Class | Video format[d] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | UHS | Video | SD Express | SD | HD | 4K | 8K | |

| 2 MB/s | Class 2 (C2) |

— | — | — | Yes | No | No | No |

| 4 MB/s | Class 4 (C4) |

Yes | ||||||

| 6 MB/s | Class 6 (C6) |

Class 6 (V6) |

Yes | |||||

| 10 MB/s | Class 10 (C10) |

Class 1 (U1) |

Class 10 (V10) | |||||

| 30 MB/s | — | Class 3 (U3) |

Class 30 (V30) |

Yes | ||||

| 60 MB/s | — | Class 60 (V60) | ||||||

| 90 MB/s | Class 90 (V90) | |||||||

| 150 MB/s | — | Class 150 (E150) | ||||||

| 300 MB/s | Class 300 (E300) | |||||||

| 450 MB/s | Class 450 (E450) | |||||||

| 600 MB/s | Class 600 (E600) | |||||||

Speed Class ratings were introduced to indicate the minimum data transfer performance of an SD card (as opposed to bus speed rating, which indicates device performance) in terms of sustained sequential write performance. This performance is important when transferring large files, especially during tasks like video recording, which requires consistent throughput to avoid dropped frames.[53]

Where speed classes overlap, manufacturers often display multiple symbols on the same card to indicate compatibility with different host devices and standards.

Original speed class (C)

[edit]The original speed class ratings—Class 2, 4, 6, and 10—specify minimum sustained write speeds of 2, 4, 6, and 10 MB/s, respectively. Class 10 cards assume a non-fragmented file system and use the High Speed bus mode.[40] These are represented by a number encircled with a "C" (e.g., C2, C4, C6 and C10).

UHS speed class (U)

[edit]Ultra High Speed (UHS) speed class ratings—U1 and U3—specify minimum sustained write speeds of 10 and 30 MB/s, respectively. These classes are represented by a number inside a "U" and are designed for high-bandwidth tasks such as 4K video recording.[75]

Video speed class (V)

[edit]Video speed class ratings—V6, V10, V30, V60, and V90—specify minimum sustained write speeds of 6, 10, 30, 60, and 90 MB/s, respectively.[76][53][77][78] These classes are represented by a stylized "V" followed by the number and were introduced to support high-resolution formats such as 4K and 8K and to align with the performance characteristics of multi-level cell NAND flash memory.[79][80]

SD Express Speed Class (E)

[edit]SD Express speed class ratings—E150, E300, E450, and E600—specify minimum sustained write speeds of 150, 300, 450, and 600 MB/s, respectively.[81] These classes are represented by a stylized "E" followed by the number, enclosed in a rounded rectangle. They are designed for data-intensive applications such as large-scale video processing, real-time analytics, and software execution.[81]

"×" rating

[edit]| Rating | Approx. (MB/s) |

Comparable speed class |

|---|---|---|

| 16× | 2.34 | |

| 32× | 4.69 | |

| 48× | 7.03 | |

| 100× | 14.6 |

Initially, some manufacturers used a "×" rating system based on the speed of a standard CD-ROM drive (150 kB/s or 1.23 Mbit/s),[e] but this approach was inconsistent and often unclear. It was later replaced by standardized Speed Class systems that specify guaranteed minimum write speeds.[40][77][82][83]

Real-world performance

[edit]Speed Class ratings guarantee minimum write performance but do not fully describe real-world speed, which can vary based on factors such as file fragmentation, write amplification due to flash memory management, controller retry operations for soft error correction and sequential vs. random write patterns.

In some cases, cards of the same speed class may perform very differently. For instance, random small-file write speeds can be significantly lower than sequential performance. A 2012 study found some Class 2 cards outperformed Class 10 cards in random writes.[84] Another test in 2014 reported a 300-fold difference in small-write performance across cards, with a Class 4 card outperforming higher-rated cards in certain use cases.[85]

Performance ratings

[edit]| Rating | Minimum random IOPS | Minimum sustained sequential writing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read | Write | ||

| Class 1 (A1) |

1,500 | 500 | 10 MB/s |

| Class 2 (A2) |

4,000 | 2,000 | |

Application Performance Class ratings were introduced in 2016 to identify SD cards capable of reliably running and storing applications, alongside general-purpose tasks such as saving photos, videos, music, and documents.

Earlier SD card speed ratings focused on sequential read and write performance, which is important when transferring large files. However, running apps and operating systems involves frequent access to many small files—a pattern known as random access—which places different demands on storage.[87] Before the introduction of the Application Performance Classes, random access performance could vary significantly between cards and presented a limiting factor in some use cases.[84][85][88]

As SD cards saw broader use for app storage and system boot volumes—especially in mobile devices, single-board computers, and embedded systems—a new performance metric became necessary.[87] This need became more pressing with Android's Adoptable Storage feature, which allows SD cards to function as internal (non-removable) storage on smartphones and tablets.[89]

To address this, the SD Association introduced Application Performance Classes. The first, A1, defined in SD Specification 5.1 (released November 2016), requires a minimum of 1,500 input/output operations per second (IOPS) for reading and 500 IOPS for writing, using 4 kB blocks. The higher-tier A2 class, defined in Specification 6.0 (released in February 2017), raises the thresholds to 4,000 read and 2,000 write IOPS. However, achieving these speeds requires host device support for command queuing and write caching, features that allow the card to optimize the execution of multiple simultaneous tasks and temporarily store data.[90] If not properly supported, performance will fall back to A1 levels. Both A1 and A2 cards must also sustain a minimum sequential write speed of 10 MB/s, equivalent to speed classes C10, U1 and V10.[91]

Features

[edit]Card security

[edit]Commands to disable writes

[edit]The host device can command the SD card to become read-only (to reject subsequent commands to write information to it). There are both reversible and irreversible host commands that achieve this.[92][93]

Write-protect notch

[edit]

Most full-size SD cards have a mechanical write-protect switch, a sliding tab over a notch on the left side (viewed from the top, with the beveled corner on the right), that signals to the device to treat the card as read-only. Sliding the tab up (toward the contacts) sets the card to read/write; sliding it down sets it to read-only. However, the switch position is not detected by the card's internal circuitry.[94] Therefore, some devices ignore it, while others allow overrides.[citation needed]

MiniSD and microSD cards lack a built-in notch but can be used with adapters that include one. Cards without a notch are always writable; cards with preloaded content have a notch but no sliding tab.[citation needed]

Card password

[edit]A host device can lock an SD card using a password of up to 16 bytes, typically supplied by the user.[citation needed] A locked card interacts normally with the host device except that it rejects commands to read and write data.[citation needed] A locked card can be unlocked only by providing the same password. The host device can, after supplying the old password, specify a new password or disable locking. Without the password (typically, in the case that the user forgets the password), the host device can command the card to erase all the data on the card for future re-use (except card data under DRM), but there is no way to gain access to the existing data.[citation needed]

Windows Phone 7 devices use SD cards designed for access only by the phone manufacturer or mobile provider. An SD card inserted into the phone underneath the battery compartment becomes locked "to the phone with an automatically generated key" so that "the SD card cannot be read by another phone, device, or PC".[95] Symbian devices, however, are some of the few that can perform the necessary low-level format operations on locked SD cards. It is therefore possible to use a device such as the Nokia N8 to reformat the card for subsequent use in other devices.[96]

smartSD cards

[edit]A smartSD memory card is a microSD card with an internal "secure element" that allows the transfer of ISO 7816 Application Protocol Data Unit commands to, for example, JavaCard applets running on the internal secure element through the SD bus.[97]

Some of the earliest versions of microSD memory cards with secure elements were developed in 2009 by DeviceFidelity, Inc.,[98][99] a pioneer in near-field communication (NFC) and mobile payments, with the introduction of In2Pay and CredenSE products, later commercialized and certified for mobile contactless transactions by Visa in 2010.[100] DeviceFidelity also adapted the In2Pay microSD to work with the Apple iPhone using the iCaisse, and pioneered the first NFC transactions and mobile payments on an Apple device in 2010.[101][102][103]

Various implementations of smartSD cards have been done for payment applications and secured authentication.[104][105] In 2012 Good Technology partnered with DeviceFidelity to use microSD cards with secure elements for mobile identity and access control.[106]

microSD cards with Secure Elements and NFC (near-field communication) support are used for mobile payments, and have been used in direct-to-consumer mobile wallets and mobile banking solutions, some of which were launched by major banks around the world, including Bank of America, US Bank and Wells Fargo,[107][108][109] while others were part of innovative new direct-to-consumer neobank programs such as moneto, first launched in 2012.[110][111][112][113]

microSD cards with Secure Elements have also been used for secure voice encryption on mobile devices, which allows for one of the highest levels of security in person-to-person voice communications.[114] Such solutions are heavily used in intelligence and security.

In 2011, HID Global partnered with Arizona State University to launch campus access solutions for students using microSD with Secure Element and MiFare technology provided by DeviceFidelity, Inc.[115][116] This was the first time regular mobile phones could be used to open doors without need for electronic access keys.

Vendor enhancements

[edit]

Vendors have sought to differentiate their products in the market through various vendor-specific features:

- Integrated Wi-Fi – Several companies produce SD cards with built-in Wi-Fi transceivers. The card lets any digital camera with an SD slot transmit captured images over a wireless network or store the images on the card's memory until it is in range of a wireless network. Some models geotag their pictures.

- Pre-loaded content – In 2006, SanDisk announced Gruvi, a microSD card with extra digital rights management features, which they intended as a medium for publishing content. SanDisk again announced pre-loaded cards in 2008, under the slotMusic name, this time not using any of the DRM capabilities of the SD card.[117] In 2011, SanDisk offered various collections of 1000 songs on a single slotMusic card for about $40,[118] now restricted to compatible devices and without the ability to copy the files.

- Integrated USB connector – Several companies produce SD cards with built-in USB connectors allowing them to be accessed by a computer without a card reader.[119]

- Integrated display – In 2006, ADATA announced a Super Info SD card with a digital display that provided a two-character label and showed the amount of unused memory on the card.[120]

SDIO cards

[edit]

SDIO (Secure Digital Input Output) is an extension of the SD specification that supports input/output (I/O) devices in addition to data storage.[121] SDIO cards are physically and electrically identical to standard SD cards but require compatible host devices with appropriate drivers to utilize their I/O functions. Common examples included adapters for GPS, Wi-Fi, cameras, barcode readers, and modems.[122] SDIO was not widely adopted.

Compatibility

[edit]Host devices that comply with newer versions of the specification provide backward compatibility and accept older SD cards.[36] For example, SDXC host devices accept all previous families of SD memory cards, and SDHC host devices also accept standard SD cards.

Older host devices generally do not support newer card formats, and even when they might support the bus interface used by the card,[32] there are several factors that arise:

- A newer card may offer greater capacity than the host device can handle (over 4 GB for SDHC, over 32 GB for SDXC).

- A newer card may use a file system the host device cannot navigate (FAT32 for SDHC, exFAT for SDXC)

- Use of an SDIO card requires the host device be designed for the input/output functions the card provides.

- The hardware interface of the card was changed starting with the version 2.0 (new high-speed bus clocks, redefinition of storage capacity bits) and SDHC family (ultra-high speed (UHS) bus)

- UHS-II has physically more pins but is backwards compatible to UHS-I and non-UHS for both slot and card.[51]

- Some vendors produced SDSC cards above 1 GB before the SDA had standardized a method of doing so.

Card Slot

|

SDSC | SDHC | SDHC UHS |

SDXC | SDXC UHS |

SDIO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDSC | Partial[f] | FAT16, < 4 GB[f] | FAT16, < 4 GB[f] | No | No | No |

| SDHC | Yes | Yes | In non-UHS mode | FAT32 | FAT32 in non-UHS mode | No |

| SDHC UHS | In non-UHS mode | In non-UHS mode | In UHS mode | FAT32 in non-UHS mode | FAT32 in UHS mode | No |

| SDXC | Yes | Yes | In non-UHS mode | Yes | In non-UHS mode | No |

| SDXC UHS | In non-UHS mode | In non-UHS mode | In UHS mode | In non-UHS mode | In UHS mode | No |

| SDIO | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | Yes |

Markets

[edit]Due to their compact size, Secure Digital cards are used in many consumer electronic devices, and have become a widespread means of storing several gigabytes of data in a small size. Devices in which the user may remove and replace cards often, such as digital cameras, camcorders and video game consoles, tend to use full-sized cards. Devices in which small size is paramount, such as mobile phones, action cameras such as the GoPro Hero series, and camera drones, tend to use microSD cards.[1][2]

Mobile phones

[edit]

microSD cards are widely used in mobile phones to expand storage, offering offline, low-latency access that benefits tasks like photography, video recording, and file transfers, especially in areas with limited connectivity or costly data plans.[123] Data on removable cards can also be preserved independently of device failure, aiding recovery.

Support for microSD is prevalent in Android smartphones.[124] In contrast, Apple has never included microSD card slots in the iPhone, relying solely on built-in flash storage and cloud services.[125]

Digital cameras

[edit]

Secure Digital memory cards can be used in Sony XDCAM EX camcorders with an adapter.[126]

Personal computers

[edit]Although many personal computers accommodate SD cards as an auxiliary storage device using a built-in slot, or can accommodate SD cards by means of a USB adapter, SD cards cannot be used as the primary hard disk through the onboard ATA controller, because none of the SD card variants support ATA signalling. Primary hard disk use requires a separate SD host controller[127] or an SD-to-CompactFlash converter. However, on computers that support bootstrapping from a USB interface, an SD card in a USB adapter can be the boot disk, provided it contains an operating system that supports USB access once the bootstrap is complete.

In laptop and tablet computers, memory cards in an integrated memory card reader offer an ergonomical benefit over USB flash drives, as the latter sticks out of the device, and the user would need to be cautious not to bump it while transporting the device, which could damage the USB port. Memory cards have a unified shape and do not reserve a USB port when inserted into a computer's dedicated card slot.

Since late 2009, newer Apple computers with installed SD card readers have been able to boot in macOS from SD storage devices, when properly formatted to Mac OS Extended file format and the default partition table set to GUID Partition Table.[43]

SD cards are increasing in usage and popularity among owners of vintage computers like Atari 8-bit computers. For example SIO2SD (SIO is an Atari port for connecting external devices) is used nowadays. Software for an 8-bit Atari may be included on one SD card that may have less than 4–8 GB of disk size (2019).[128]

Embedded systems

[edit]

In 2008, the SDA specified Embedded SD, "leverag[ing] well-known SD standards" to enable non-removable SD-style devices on printed circuit boards.[129] However this standard was not adopted by the market while the MMC standard became the de facto standard for embedded systems. SanDisk provides such embedded memory components under the iNAND brand.[130]

While some modern microcontrollers integrate SDIO hardware which uses the faster proprietary four-bit SD bus mode, almost all modern microcontrollers at least have SPI units that can interface to an SD card operating in the slower one-bit SPI bus mode. If not, SPI can also be emulated by bit banging (e.g. a SD card slot soldered to a Linksys WRT54G-TM router and wired to GPIO pins using DD-WRT's Linux kernel achieved only 1.6 Mbit/s throughput).[131]

Music distribution

[edit]Prerecorded microSDs have been used to commercialize music under the brands slotMusic and slotRadio by SanDisk and MQS by Astell & Kern.

Counterfeits

[edit]Commonly found on the market are mislabeled or counterfeit Secure Digital cards that report a fake capacity or run slower than labeled.[132][133][134] Software tools exist to check and detect counterfeit products,[135][136][137] and in some cases it is possible to repair these devices to remove the false capacity information and use its real storage limit.[138]

Detection of counterfeit cards usually involves copying files with random data to the SD card until the card's capacity is reached, and copying them back. The files that were copied back can be tested either by comparing checksums (e.g. MD5), or trying to compress them. The latter approach leverages the fact that counterfeited cards let the user read back files, which then consist of easily compressible uniform data (for example, repeating 0xFFs).

-

Images of genuine, questionable, and counterfeit microSD cards before and after decapsulation. Details at source.

Technical details

[edit]Physical size

[edit]

The SD card specification defines three physical sizes. The SD and SDHC families are available in all three sizes, but the SDXC and SDUC families are not available in the mini size, and the SDIO family is not available in the micro size. Smaller cards are usable in larger slots through use of a passive adapter.

Standard

[edit]- SD (SDSC), SDHC, SDXC, SDIO, SDUC

- 32 mm × 24 mm × 2.1 mm (1+17⁄64 in × 15⁄16 in × 5⁄64 in)

- 32 mm × 24 mm × 1.4 mm (1+17⁄64 in × 15⁄16 in × 1⁄16 in) (as thin as MMC) for Thin SD (rare)

MiniSD

[edit]- miniSD, miniSDHC, miniSDIO

- 21.5 mm × 20 mm × 1.4 mm (27⁄32 in × 25⁄32 in × 1⁄16 in)

microSD

[edit]The micro form factor is the smallest SD card format.[139]

- microSD, microSDHC, microSDXC, microSDUC

- 15 mm × 11 mm × 1 mm (19⁄32 in × 7⁄16 in × 3⁄64 in)

Transfer modes

[edit]Cards may support various combinations of the following bus types and transfer modes. The SPI bus mode and one-bit SD bus mode are mandatory for all SD families, as explained in the next section. Once the host device and the SD card negotiate a bus interface mode, the usage of the numbered pins is the same for all card sizes.

- SPI bus mode: Serial Peripheral Interface Bus is primarily used by embedded microcontrollers. This bus type supports only a 3.3-volt interface. This is the only bus type that does not require a host license.[citation needed]

- One-bit SD bus mode: Separate command and data channels and a proprietary transfer format.

- Four-bit SD bus mode: Uses extra pins plus some reassigned pins. This is the same protocol as the one-bit SD bus mode which uses one command and four data lines for faster data transfer. All SD cards support this mode. UHS-I and UHS-II require this bus type.

- Two differential lines SD UHS-II mode: Uses two low-voltage differential signaling interfaces to transfer commands and data. UHS-II cards include this interface in addition to the SD bus modes.

The physical interface comprises 9 pins, except that the miniSD card adds two unconnected pins in the center and the microSD card omits one of the two VSS (Ground) pins.[140]

| MMC pin |

SD pin |

miniSD pin |

microSD pin |

Name | I/O | Logic | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | nCS | I | PP | SPI Card Select [CS] (Negative logic) |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | DI | I | PP | SPI Serial Data In [MOSI] |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | VSS | S | S | Ground | |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | VDD | S | S | Power |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | CLK | I | PP | SPI Serial Clock [SCLK] |

| 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | VSS | S | S | Ground |

| 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | DO | O | PP | SPI Serial Data Out [MISO] |

| 8 | 8 | 8 | NC nIRQ |

. O |

. OD |

Unused (memory cards) Interrupt (SDIO cards) (negative logic) | |

| 9 | 9 | 1 | NC | . | . | Unused | |

| 10 | NC | . | . | Reserved | |||

| 11 | NC | . | . | Reserved |

| MMC pin |

SD pin |

miniSD pin |

microSD pin |

Name | I/O | Logic | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | CD | I/O | . | Card detection (by host) and non-SPI mode detection (by card) |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | CMD | I/O | PP, OD |

Command, Response |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | VSS | S | S | Ground | |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | VDD | S | S | Power |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | CLK | I | PP | Serial clock |

| 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | VSS | S | S | Ground |

| 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | DAT0 | I/O | PP | SD Serial Data 0 |

| 8 | 8 | 8 | NC nIRQ |

. O |

. OD |

Unused (memory cards) Interrupt (SDIO cards) (negative Logic) | |

| 9 | 9 | 1 | NC | . | . | Unused | |

| 10 | NC | . | . | Reserved | |||

| 11 | NC | . | . | Reserved |

| MMC pin |

SD pin |

miniSD pin |

microSD pin |

Name | I/O | Logic | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 | 1 | 2 | DAT3 | I/O | PP | SD Serial Data 3 |

| . | 2 | 2 | 3 | CMD | I/O | PP, OD |

Command, Response |

| . | 3 | 3 | VSS | S | S | Ground | |

| . | 4 | 4 | 4 | VDD | S | S | Power |

| . | 5 | 5 | 5 | CLK | I | PP | Serial clock |

| . | 6 | 6 | 6 | VSS | S | S | Ground |

| . | 7 | 7 | 7 | DAT0 | I/O | PP | SD Serial Data 0 |

| 8 | 8 | 8 | DAT1 nIRQ |

I/O O |

PP OD |

SD Serial Data 1 (memory cards) Interrupt Period (SDIO cards share pin via protocol) | |

| 9 | 9 | 1 | DAT2 | I/O | PP | SD Serial Data 2 | |

| 10 | NC | . | . | Reserved | |||

| 11 | NC | . | . | Reserved |

Notes:

- Direction is relative to card. I = Input, O = Output.

- PP = Push-Pull logic, OD = Open-Drain logic.

- S = Power Supply, NC = Not Connected (or logical high).

Interface

[edit]

Command interface

[edit]SD cards and host devices initially communicate through a synchronous one-bit interface, where the host device provides a clock signal that strobes single bits in and out of the SD card. The host device thereby sends 48-bit commands and receives responses. The card can signal that a response will be delayed, but the host device can abort the dialogue.[40]

Through issuing various commands, the host device can:[40]

- Determine the type, memory capacity and capabilities of the SD card

- Command the card to use a different voltage, different clock speed, or advanced electrical interface

- Prepare the card to receive a block to write to the flash memory, or read and reply with the contents of a specified block.

The command interface is an extension of the MultiMediaCard (MMC) interface. SD cards dropped support for some of the commands in the MMC protocol, but added commands related to copy protection. By using only commands supported by both standards until determining the type of card inserted, a host device can accommodate both SD and MMC cards.

Electrical interface

[edit]All SD card families initially use a 3.3 volt electrical interface. On command, SDHC and SDXC cards can switch to 1.8 V operation.[40]

At power-up or card insertion, the voltage on pin 1 selects either the Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) bus or the SD bus. The SD bus starts in one-bit mode, but the host device may issue a command to switch to the four-bit mode, if the SD card supports it. For various card types, support for the four-bit SD bus is either optional or mandatory.[40]

After determining that the SD card supports it, the host device can also command the SD card to switch to a higher transfer speed. Until determining the card's capabilities, the host device should not use a clock speed faster than 400 kHz. SD cards other than SDIO (see below) have a "Default Speed" clock rate of 25 MHz. The host device is not required to use the maximum clock speed that the card supports. It may operate at less than the maximum clock speed to conserve power.[40] Between commands, the host device can stop the clock entirely.

MBR and FAT

[edit]Most SD cards ship preformatted with one or more MBR partitions, where the first or only partition contains a file system. This lets them operate like the hard disk of a personal computer. Per the SD card specification, an SD card is formatted with MBR and the following file system:

- For SDSC cards:

- Capacity of less than 32,680 logical sectors (smaller than 16 MB[g]): FAT12 with partition type 01h and BPB 3.0 or EBPB 4.1[141]

- Capacity of 32,680 to 65,535 logical sectors (between 16 MB and 32 MB):[g] FAT16 with partition type 04h and BPB 3.0 or EBPB 4.1[141]

- Capacity of at least 65,536 logical sectors (larger than 32 MB):[g] FAT16B with partition type 06h and EBPB 4.1[141]

- For SDHC cards:

- For SDXC cards: exFAT with partition type 07h

Most consumer products that take an SD card expect that it is partitioned and formatted in this way. Universal support for FAT12, FAT16, FAT16B and FAT32 allows the use of SDSC and SDHC cards on most host computers with a compatible SD reader, to present the user with the familiar method of named files in a hierarchical directory tree.[citation needed]

On such SD cards, standard utility programs such as Mac OS X's "Disk Utility" or Windows' SCANDISK can be used to repair a corrupted filing system and sometimes recover deleted files. Defragmentation tools for FAT file systems may be used on such cards. The resulting consolidation of files may provide a marginal improvement in the time required to read or write the file,[142] but not an improvement comparable to defragmentation of hard drives, where storing a file in multiple fragments requires additional physical and relatively slow, movement of a drive head.[citation needed] Moreover, defragmentation performs writes to the SD card that count against the card's rated lifespan. The write endurance of the physical memory is discussed in the article on flash memory; newer technology to increase the storage capacity of a card provides worse write endurance.[citation needed]

When reformatting an SD card with a capacity of at least 32 MB[g] (65,536 logical sectors or more), but not more than 2 GB,[b] FAT16B with partition type 06h and EBPB 4.1[141] is recommended if the card is for a consumer device. (FAT16B is also an option for 4 GB cards, but it requires the use of 64 KB clusters, which are not widely supported.) FAT16B does not support cards above 4 GB[b] at all.

The SDXC specification mandates the use of Microsoft's proprietary exFAT file system,[143] which sometimes requires appropriate drivers (e.g. exfat-utils/exfat-fuse on Linux).

Risks of reformatting

[edit]Reformatting an SD card with a different file system, or even with the same one, may make the card slower, or shorten its lifespan. Some cards use wear leveling, in which frequently modified blocks are mapped to different portions of memory at different times, and some wear-leveling algorithms are designed for the access patterns typical of FAT12, FAT16 or FAT32.[144] In addition, the preformatted file system may use a cluster size that matches the erase region of the physical memory on the card; reformatting may change the cluster size and make writes less efficient. The SD Association provides freely downloadable SD Formatter software to overcome these problems for Windows and Mac OS X.[145]

SD/SDHC/SDXC memory cards have a "Protected Area" on the card for the SD standard's security function. Neither standard formatters nor the SD Association formatter will erase it. The SD Association suggests that devices or software which use the SD security function may format it.[145]

Power consumption

[edit]The power consumption of SD cards varies by its speed mode, manufacturer and model.[citation needed]

During transfer it may be in the range of 66–330 mW (20–100 mA at a supply voltage of 3.3 V). Specifications from TwinMOS Technologies list a maximum of 149 mW (45 mA) during transfer. Toshiba lists 264–330 mW (80–100 mA).[146] Standby current is much lower, less than 0.2 mA for one 2006 microSD card.[147] If there is data transfer for significant periods, battery life may be reduced noticeably; for reference, the capacity of smartphone batteries is typically around 6 Wh (Samsung Galaxy S2: 1650 mAh @ 3.7 V).

Modern UHS-II cards can consume up to 2.88 W, if the host device supports bus speed mode SDR104 or UHS-II. Minimum power consumption in the case of a UHS-II host is 720 mW.[citation needed]

| Bus speed mode |

Max. bus speed [MB/s] |

Max. clock frequency [MHz] |

Signal voltage [V] |

SDSC [W] |

SDHC [W] |

SDXC [W] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD312 | 312 | 52 | 0.4 | – | 2.88 | 2.88 |

| FD156 | 156 | 52 | 0.4 | – | 2.88 | 2.88 |

| SDR104 | 104 | 208 | 1.8 | – | 2.88 | 2.88 |

| SDR50 | 50 | 100 | 1.8 | – | 1.44 | 1.44 |

| DDR50 | 50 | 50 | 1.8 | – | 1.44 | 1.44 |

| SDR25 | 25 | 50 | 1.8 | – | 0.72 | 0.72 |

| SDR12 | 12.5 | 25 | 1.8 | – | 0.36 | 0.36 / 0.54 |

| High Speed | 25 | 50 | 3.3 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.72 |

| Default Speed | 12.5 | 25 | 3.3 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.36 / 0.54 |

Storage capacity and compatibilities

[edit]All SD cards let the host device determine how much information the card can hold, and the specification of each SD family gives the host device a guarantee of the maximum capacity a compliant card reports.

By the time the version 2.0 (SDHC) specification was completed in June 2006,[148] vendors had already devised 2 GB and 4 GB SD cards, either as specified in Version 1.01, or by creatively reading Version 1.00. The resulting cards do not work correctly in some host devices.[149][150]

SDSC cards above 1 GB

[edit]

SD version 1.00 assumed 512 bytes per block. This permitted SDSC cards up to 4,096 × 512 × 512 B = 1 GB.[b]

Version 1.01 let an SDSC card use a 4-bit field to indicate 1,024 or 2,048 bytes per block instead.[40] Doing so enabled cards with 2 GB and 4 GB capacity, such as the Transcend 4 GB SD card, the Memorette 4 GB SD card and the Hoco 4 GB microSD card.[citation needed]

Storage capacity calculations

[edit]The format of the Card-Specific Data (CSD) register changed between version 1 (SDSC) and version 2.0 (which defines SDHC and SDXC).

Version 1

[edit]In version 1 of the SD specification, capacities up to 2 GB[b] are calculated by combining fields of the CSD as follows:

Capacity = (C_SIZE + 1) × 2(C_SIZE_MULT + READ_BL_LEN + 2) where 0 ≤ C_SIZE ≤ 4095, 0 ≤ C_SIZE_MULT ≤ 7, READ_BL_LEN is 9 (for 512 bytes/sector) or 10 (for 1024 bytes/sector)

Later versions state (at Section 4.3.2) that a 2 GB SDSC card shall set its READ_BL_LEN (and WRITE_BL_LEN) to indicate 1,024 bytes, so that the above computation correctly reports the card's capacity, but that, for consistency, the host device shall not request (by CMD16) block lengths over 512 B.[40]

Versions 2 and 3

[edit]In the definition of SDHC cards in version 2.0, the C_SIZE portion of the CSD is 22 bits and it indicates the memory size in multiples of 512 KB (the C_SIZE_MULT field is removed and READ_BL_LEN is no longer used to compute capacity). Two bits that were formerly reserved now identify the card family: 0 is SDSC; 1 is SDHC or SDXC; 2 and 3 are reserved.[40] Because of these redefinitions, older host devices do not correctly identify SDHC or SDXC cards nor their correct capacity.

- SDHC cards are restricted to reporting a capacity not over 32 GB.[citation needed]

- SDXC cards are allowed to use all 22 bits of the C_SIZE field. An SDHC card that did so (reported C_SIZE > 65,375 to indicate a capacity of over 32 GB) would violate the specification. A host device that relied on C_SIZE rather than the specification to determine the card's maximum capacity might support such a card, but the card might fail in other SDHC-compatible host devices.[citation needed]

Capacity is calculated thus:

Capacity = (C_SIZE + 1) × 524288 where for SDHC 4112 ≤ C_SIZE ≤ 65375 ≈2 GB ≤ Capacity ≤ ≈32 GB where for SDXC 65535 ≤ C_SIZE ≈32 GB ≤ Capacity ≤ 2 TB[citation needed]

Capacities above 4 GB can only be achieved by following version 2.0 or later versions. In addition, capacities equal to 4 GB must also do so to guarantee compatibility.[citation needed]

Data recovery

[edit]A malfunctioning SD card can be repaired using specialized equipment, as long as the middle part, containing the flash storage, is not physically damaged. The controller can in this way be circumvented. This might be harder or even impossible in the case of monolithic card, where the controller resides on the same physical die.[151][152]

Adapters

[edit]Various passive adapters are available to allow smaller SD cards to work in larger SD card slots.

-

Dismantled microSD to SD adapter showing the passive connection from the microSD card slot on the bottom to the SD pins on the top

-

MicroSD-to-SD adapter (left), microSD-to-miniSD adapter (middle), microSD card (right)

-

MiniSD memory card including adapter

-

microSD card (left), microSD to SD card adapter (right)

-

microSD card inserted into microSD to SD card adapter

-

In 2008 Olympus started bundling microSD card to xD-Picture Card adapters with their digital cameras

Openness of specification

[edit]The SD format was introduced in August 1999.[7] Like most memory card formats, SD is covered by patents and trademarks. Royalties apply to the manufacture and sale of SD cards and host adapters, with the exception of SDIO devices. As of 2025, the SD Association (SDA) charged annual membership fees of US$2,500 for general members and US$4,500 for executive members.[153]

Early versions of the SD specification were only available under a non-disclosure agreement (NDA), which restricted the development of open-source drivers. Despite these limitations, developers reverse-engineered the interface and created free software drivers for SD cards that did not use digital rights management (DRM).[154]

In 2006, the SDA began publishing a "Simplified Specification" under a less restrictive license. It includes documentation for the physical layer, SDIO, and certain extensions, allowing broader implementation without requiring an NDA or paid membership.[155][156]

Revisions

[edit]| Ver. | Year | Notable changes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.00 | 2000 | Preliminary specification | — |

| 1.01 | 2001 | Minor updates | [34] |

| 1.10 | 2006 | Official initial release | [157] |

| 2.00 | Added SDHC and Speed Classes C2, C4, and C6[158] | [35] | |

| 3.01 | 2010 | Added SDXC, UHS-I bus and Speed Class C10/UHS Speed Class U1 | [40] |

| 4.10 | 2013 | Added UHS-II bus, UHS Speed Class U3, and enhanced power and function support | [140] |

| 5.00 | 2016 | Added Video Speed Classes V6, V10, V30, V60, and V90 | [159] |

| 5.10 | Added Application Performance Class A1 | [90] | |

| 6.00 | 2017 | Added Application Performance Class A2 (with command queuing and write caching) and Card Ownership Protection | [62] |

| 7.10 | 2020 | Added SD Express, microSD Express, SDUC, and made CPRM optional | [160] |

| 8.00 | Added PCIe 4.0, added dual-lane PCIe on full-size cards | [161] | |

| 9.00 | 2022 | Introduced new security features and enhanced write protection | [94] |

| 9.10 | 2023 | Added SD Express Speed Classes E150, E300, E450, and E600 | [162] |

See also

[edit]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ except where indicated otherwise, 1 MB equals one million bytes

- ^ a b c d e f g here, 1 GB = 1 GiB = 230 B

- ^ a b here, 1 TB = 10244 B

- ^ The necessary recording and playback speed class requirements may vary by device.

- ^ 1 KB = 1024 B

- ^ a b c See discussion about storage capacity and compatibilities.

- ^ a b c d here, MB = 10242 B

References

[edit]- ^ a b "4 Features and Benefits of a Micro SD Transflash Memory Card – Steve's Digicams". steves-digicams.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Advantages and Disadvantages of Memory Cards". Engadget. October 11, 2016. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ "Matsushita Electric, SanDisk and Toshiba to Form SD Association to Promote Next Generation SD Memory Card". Toshiba. March 30, 2015. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ "Using SD Memory Cards is Easy". SD Association. June 22, 2010. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Shendar, Ronni (September 29, 2022). "The Invention of the SD Card: When Tiny Storage Met Tech Giants". Western Digital. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ Andrews, Ben (October 25, 2022). "Flash back: the history of the SD card, and why we think it deserves more love". Digital Photography Review. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ a b "Matsushita Electric, SanDisk and Toshiba Agree to Join Forces to Develop and Promote Next Generation Secure Memory Card". DP Review. August 24, 1999. Archived from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ The Odd History of the SD Logo. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ "Press Releases 17 July 2003". Toshiba. July 17, 2003. Archived from the original on September 8, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "SanDisk SD Card Product Family" (PDF). SanDisk. June 2007.

- ^ "Definition of CPRM". PCMAG. Archived from the original on April 29, 2025. Retrieved April 29, 2025.

- ^ "Copyright Protection for Digital Data (CPRM)". SD Association. Archived from the original on April 29, 2025. Retrieved April 29, 2025.

- ^ "Three Giants to develop new "Secure Memory Card"". Digital Photography Review. August 25, 1999. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ Udinmwen, Efosa (May 24, 2025). "SD memory cards just hit 25—cloud storage won't kill them, and here's why they're still irreplaceable". TechRadar. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ Kantra Kirschner, Suzanne, ed. (August 27, 2000). "Electronics – Memory Cards". Popular Science. p. 40. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ "About the SD Association". Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ "SanDisk Introduces The World's Smallest Removable Flash Card For Mobile Phones—The miniSD Card". SanDisk. March 13, 2003. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009.

- ^ Buchanan, Matt (October 1, 2008). "Giz Explains: An Illustrated Guide to Every Stupid Memory Card You Need". Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ "HD録画のカムコーダ、DVD-R内蔵ミニノート......会場で見かけた新製品". ITmedia NEWS. March 22, 2004. Archived from the original on September 11, 2024. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ Rojas, Peter (March 2, 2004). "T-Flash: aka 'Yet Another Memory Card Format'". Engadget. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ "TransFlash becomes MicroSD". Archived from the original on September 11, 2024. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ "SanDisk Reveals Tiny New Memory Cards for Phones". Phonescoop. February 28, 2004. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ Williams, Lynnae (January 9, 2024). "TF Card: What Is It, And What's It Used For?". SlashGear. Retrieved July 11, 2025.

- ^ "SDXC SIGNALS NEW GENERATION OF REMOVABLE MEMORY WITH UP TO 2 TERABYTES OF STORAGE" (PDF). sdcard.org. SD Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2024. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Capacity (SD/SDHC/SDXC/SDUC)". SD Association. December 11, 2020. Archived from the original on September 11, 2024. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "Pretec introduces world's first SDXC card". Digital Photography Review. March 6, 2009. Archived from the original on August 21, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Conneally, Tim (March 16, 2011). "Lexar ships 128 GB Class 10 SDXC card; March 2011". Betanews.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2023. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "SanDisk's 1 TB microSD card is now available". theverge.com. May 15, 2019. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ "SDUC Spec". Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ "Представлена первая в мире карта памяти MicroSDXC ёмкостью 2 ТБ". iXBT.com (in Russian). September 29, 2022. Archived from the original on January 12, 2025. Retrieved April 3, 2025.

- ^ "Western Digital Showcases New Super Speeds and Massive Capacities for M&E Workflows at NAB 2024". westerndigital.com. April 11, 2024. Archived from the original on September 11, 2024. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ a b "Using SDXC". SD Association. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ "SDIO". SD Association. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "SD Part 1, Physical Layer Simplified Specification, Version 1.01" (PDF). SD Association. April 15, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 15, 2025.

- ^ a b "SD Part 1, Physical Layer Simplified Specification, Version 2.00" (PDF). SD Association. September 25, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2025.

- ^ a b "SD Card Compatibility". SD Association. Archived from the original on November 21, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- ^ "934428 – Hotfix for Windows XP that adds support for SDHC cards that have a capacity of more than 4 GB". Support. Microsoft. February 15, 2008. Archived from the original on January 3, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "939772 – Some Secure Digital (SD) cards may not be recognized in Windows Vista". Support. Microsoft. May 15, 2008. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "949126 – A Secure Digital High Capacity (SDHC) card is not recognized on a Windows Vista Service Pack 1-based computer". Support. Microsoft. February 21, 2008. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "SD Part 1, Physical Layer Simplified Specification, Version 3.01" (PDF). SD Association. May 18, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Capacity (SD/SDHC/SDXC)". SD Association. Archived from the original on November 21, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ^ "Notable Changes in Windows Vista Service Pack 1". TechNet. Microsoft Docs. July 25, 2008. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "About the SD and SDXC card slots". Apple Inc. May 3, 2011. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "Apple released exFAT support in OS X 10.6.5 update". Tuxera.com. November 22, 2010. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ "The Initial exFAT Driver Queued For Introduction With The Linux 5.4 Kernel". phoronix.com. August 30, 2019. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ deKay (January 15, 2015). "Updated: How to upgrade your 3DS SD card, to 64 GB and beyond". Lofi-Gaming. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- ^ List, Jenny (November 29, 2017). "Ask Hackaday: How On Earth Can A 2004 MP3 Player Read An SDXC Card?". Hackaday. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- ^ Sims, Gary (May 9, 2016). "High capacity microSD cards and Android – Gary explains". Android Authority. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- ^ a b "SD Express Cards with Pie and Name Interfaces" (PDF). SD Association: 9. June 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 12, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "Bus Speed (Default Speed/High Speed/UHS/SD Express)". SD Association. December 11, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e "Bus Speed (Default Speed/ High Speed/ UHS)". SD Association. Archived from the original on October 4, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ "SD cards branded with an upper-case 'I' are faster, yo". Engadget. June 24, 2010. Archived from the original on August 28, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c "SD Speed Class". SD Association. Archived from the original on December 21, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ "SD Standard Overview". SD Association. December 11, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- ^ "SanDisk QuickFlow Technology tech brief" (PDF). SanDisk. 2022. Retrieved July 14, 2025.

- ^ "GL3232". Genesys Logic. Archived from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Lexar Professional 1066x microSDXC UHS-I Card SILVER Series". Lexar. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ "Canvas Go! Plus Class 10 microSD Cards – V30, A2 – 64 GB–512 GB". Kingston Technology Company. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ "Association Triples Speeds with UHS-II" (PDF). SD Card. January 5, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 21, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Cunningham, Andrew (April 3, 2025). "Explaining MicroSD Express cards and why you should care about them". Ars Technica. Retrieved June 30, 2025.

- ^ "UHS-II camera list". memorycard-lab.com. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ a b "SD Part 1, Physical Layer Simplified Specification, Version 6.00" (PDF). SD Association. April 10, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 6, 2025.

- ^ "SD Association Doubles Bus Interface Speeds with UHS-III" (PDF). February 23, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ Cunningham, Andrew (February 28, 2024). "Speedy "SD Express" cards have gone nowhere for years, but Samsung could change that". Ars Technica. Retrieved June 30, 2025.

- ^ Barnatt, Christopher (January 5, 2025). Explaining SD Cards (Video). ExplainingComputers. Retrieved June 30, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ "When microSD Cards Turn Against You". NCC Group. May 19, 2022.

- ^ "SD Express Card Spec Announced – PCIe + NVMe Up To 985 MB/s". AnandTech. June 27, 2018. Archived from the original on April 12, 2025. Retrieved April 12, 2025.

- ^ Gartenberg, Chain (February 25, 2019). "Memory cards are about to get much faster with new microSD Express spec". The Verge. Archived from the original on March 15, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Henchman, Mark (February 25, 2019). "The microSD Express standard combines PCI Express speeds, microSD convenience". Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ "SDExpress Delivers New Gigabtye Speeds For SDMemory Cards" (PDF). SD card (Press release). SD association. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ Cunningham, Andrew (February 28, 2024). "Speedy "SD Express" cards have gone nowhere for years, but Samsung could change that". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on April 9, 2025. Retrieved April 9, 2025.

- ^ Anderson, Robert (April 4, 2025). "You Can Already Buy Switch 2 Compatible MicroSD Express Cards". IGN. Retrieved April 9, 2025.

- ^ Barnatt, Christopher (June 29, 2025). Testing MicroSD Express: Very Fast SD Storage (Video). ExplainingComputers. Retrieved June 30, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Speed Class | SD Association". www.sdcard.org. December 11, 2020. Archived from the original on January 4, 2025. Retrieved January 7, 2025.

- ^ "NEW SDXC AND SDHC MEMORY CARDS SUPPORT 4K2K VIDEO" (PDF). SD Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ "NEW SD ASSOCIATION VIDEO SPEED CLASS SUPPORTS 8K AND MULTI-FILE VIDEO RECORDING" (PDF). SD Association. February 26, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ a b "Speed Class Standards for Video Recording – SD Association". sdcard.org. December 11, 2020. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- ^ Chaundy, Fabian (February 26, 2016). "New Video Speed Class for SD Cards". cinema5D. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Video Speed Class: The new capture protocol of SD 5.0" (PDF). SD Association. February 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 23, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ Shilov, Anton (March 1, 2016). "SD Association Announces SD 5.0 Specification: SD Cards For UHD and 360° Video Capture". Anand Tech. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ a b "New SD Express Specifications Introduce New Speed Classes and Next-Level Performance Features | SD Association". www.sdcard.org. October 27, 2023. Archived from the original on April 1, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ "SD Standards Brochure 2017" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ "Flash Memory Cards and X-Speed Ratings". Kingston. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ^ a b Kim, H.; Agrawal, N.; Ungureanu, C. (January 30, 2012). Revisiting Storage for Smartphones (PDF). USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST). NEC Laboratories America. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2012. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

Speed class considered irrelevant: our benchmarking reveals that the "speed class" marking on SD cards is not necessarily indicative of application performance; although the class rating is meant for sequential performance, we find several cases in which higher-grade SD cards performed worse than lower-grade ones overall.

- ^ a b Lui, Gough (January 16, 2014). "SD Card Sequential, Medium & Small Block Performance Round-Up". Gough's techzone. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

Variations in 4k small block performance saw a difference of approximately 300-fold between the fastest and slowest cards. Distressingly, many of the tested cards were mediocre to poor on that metric, which may explain why running updates on Linux running off SD cards can take a very long time.

- ^ "Application Performance Class". SD Association. December 11, 2020. Archived from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2025.

- ^ a b Geerling, Jeff (July 22, 2019). "A2-class microSD cards offer no better performance for the Raspberry Pi". jeffgeerling.com. Retrieved June 5, 2025.

- ^ "Raspberry Pi forum: SD card benchmarks". Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ "Adoptable storage". Android Open Source Project. Archived from the original on April 12, 2025. Retrieved April 12, 2025.

- ^ a b Pinto, Yosi (March 24, 2017). "Applications in Action: Introducing the Newest Application Performance Class". SD Association. Retrieved June 20, 2025.

- ^ "Application Performance Class: The new class of performance for applications on SD memory cards (SD 5.1)" (PDF). SD Association. November 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

- ^ By (January 19, 2014). "The Tiniest SD Card Locker". Hackaday. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ US patent 7827370

- ^ a b c d e f "SD Part 1, Physical Layer Simplified Specification, Version 9.00" (PDF). SD Association. August 22, 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 15, 2025.

- ^ "Windows Phone 7 – Microsoft Support". support.microsoft.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ "Windows Phone 7's microSD mess: the full story (and how Nokia can help you out of it)". Engadget. November 17, 2010. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ "Activating New Mobile Services and Business Models with smartSD Memory cards" (PDF). SD Association. November 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 23, 2016. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ Clark, Sarah (November 11, 2009). "DeviceFidelity launches low cost microSD-based NFC solution". nfcw.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "DeviceFidelity rolls out microSD payment tool". SecureIDNews. November 10, 2009. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Visa and DeviceFidelity Collaborate to Accelerate Adoption of Mobile Contactless Payments". visa.com. February 15, 2010. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "In2Pay is the name of Visa and DeviceFidelity's money-grubbing iPhone case". Engadget. May 18, 2010. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Device Fidelity's Amitaabh Mohortra Speaks about their micro NFC device for almost any phone". youtube.com. October 26, 2013. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ Clark, Mike (September 23, 2010). "DeviceFidelity adds NFC microSD support for iPhone 4". nfcw.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "smartSD Memory Cards". SD Association. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ "MicroSD Vendor Announces Taiwanese M-Payment Trial Using HTC NFC Phones". NFC Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ Hudson, Andrew (December 10, 2012). "DeviceFidelity's Good Vault provides identity and access solution for iOS". SecureIDNews. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Datacard Group, DeviceFidelity and U.S. Bank Announce New Smart Card and Mobile Payment Program" (Press release). Datacard Group. January 14, 2013. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021 – via Businesswire.

- ^ Clark, Sarah (August 19, 2010). "Bank of America to run NFC payments trial in New York". nfcw.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Wells Fargo to Roll Out Mobile Payments Pilot; Visa Demonstrating Capability at CARTES 2010 | Business Wire". Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ "DeviceFidelity and SpringCard Launch moneto, the World's First Multi-Platform Mobile Wallet for iPhone and Android at CES" (Press release). DeviceFidelity. January 10, 2012. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2021 – via Cision.

- ^ Clark, Sarah (September 11, 2012). "Moneto to bring NFC payments to Europe". nfcw.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Garanti Bank deploys NFC services on microSD". RFID Ready. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ "DeviceFidelity launches new range of NFC microSD devices". NFC World+. October 31, 2012. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ "iPhone Voice Encryption from KoolSpan and DeviceFidelity". koolspan.com. March 11, 2013. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ Corum, Chris (September 14, 2011). "Arizona students first to trial mobile phones with NFC for door access". CR80 News. Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Case Study: Mobile Access Pilot at Arizona State University". youtube.com. October 14, 2011. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ Robson, Wayde (September 22, 2008). "AudioHolics". AudioHolics. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "slotRadio". SanDisk. Archived from the original on November 24, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ "SanDisk Ultra II SD Plus USB/SD card", The Register, UK, July 25, 2005, archived from the original on August 8, 2019, retrieved September 11, 2024

- ^ "A-DATA Super Info SD Card 512 MB". Tech power up. February 20, 2007. Archived from the original on May 18, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2011.

- ^ "Understanding SD, SDIO and MMC Interface". Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ "SDIO / iSDIO Specification Overview". SD Association. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ "The Best microSD Cards for 2024". PCMag. December 15, 2024. Retrieved June 20, 2025.

- ^ "Inside Marshmallow: Adoptable Storage". Android Central. November 15, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2025.

- ^ "microSD memory cards and their importance with smartphones". SD Association. May 24, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2025.

- ^ "MEAD-SD01 SDHC card adapter (Sony)". Pro.sony.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "TS-7800 Embedded". Embeddedarm.com. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "SIO2SD for 8-bit Atari". May 9, 2016. Archived from the original on October 13, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ "Embedded SD". SD Association. Archived from the original on November 21, 2011. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- ^ "iNAND Embedded Flash Drives". SanDisk. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- ^ "Linksys WRT54G-TM SD/MMC mod – DD-WRT Wiki". Dd-wrt.com. February 22, 2010. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ bunnie. "On MicroSD Problems". bunniestudios.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2024. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ Schnurer, Georg (February 28, 2007). "Gefälschte SD-Karten" [Fake SD-cards] (in German). Heise mobile – c't magazin für computertechnik. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ Feddern, Boi (March 18, 2013). "Smartphones wählerisch bei microSDHC-Karten" (in German). Heise mobile – c't magazin für computertechnik. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2013.