Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

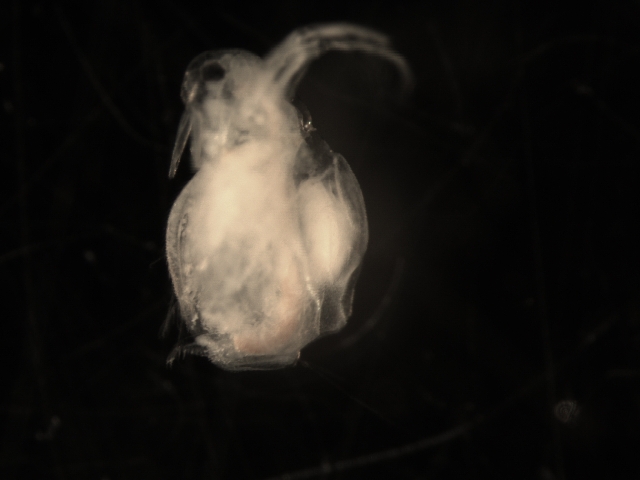

Moina

View on Wikipedia

| Moina | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Branchiopoda |

| Superorder: | Diplostraca |

| Order: | Anomopoda |

| Family: | Moinidae |

| Genus: | Moina Baird, 1850 [1] |

| Type species | |

| Moina brachiata (Jurine, 1820) [2]

| |

Moina is a genus of crustacean within the family Moinidae,[3][4] which are part of the group referred to as water fleas; they are related to the larger-bodied Daphnia species such as Daphnia magna and Daphnia pulex, though not closely.[5] This genus was first described by W. Baird in 1850.

Moina demonstrates the ability to survive in habitats with adverse biological conditions, these being waters containing low oxygen levels and of a high salinity and other impurities; these habitats include salt pans but also eutrophic water bodies.[6] An example of such an extreme habitat is the highly saline Makgadikgadi Pans of Botswana, which support prolific numbers of Moina belli.[7] The genus is also known from bodies of water across Eurasia, where research indicated previously unknown species diversity in Northern Eurasia, including Japan and China;[8] the newly described groups includes a number of phylogroups were discovered from Northern Eurasia, four new Moina species from Japan, and five new lineages in China. According to genetic data, the genus Moina is divided into two genetic lineages: the European-Western Siberian and Eastern Siberian-Far Eastern, with a transitional zone at the Yenisei River basin of Eastern Siberia.[9][10]

At least four species of Moina are known to have been introduced to non-native waterways.[11]

Species

[edit]Moina contains these species:[3][1]

- Moina affinis Birge, 1893

- Moina australiensis G.O. Sars, 1896

- Moina baringoensis Jenkin, 1934

- Moina baylyi Forró, 1985

- Moina belli Gurney, 1904

- Moina brachiata (Jurine, 1820) (armed waterflea)

- Moina brachycephala Goulden, 1968

- Moina brevicaudata Вär, 1924

- Moina chankensis Uénо, 1939

- Moina diksamensis Van Damme & Dumont, 2008

- Moina dubia Guerne & Richard, 1892

- Moina dumonti Kotov et al., 2005

- Moina elliptica (Аrоrа, 1931)

- Moina ephemeralis Hudec, 1997

- Moina eugeniae Olivier, 1954

- Moina flexuosa G.O. Sars, 1896

- Moina geei Brehm, 1933

- Moina gouldeni Mirabdullaev, 1993

- Moina hartwigi Weltner, 1899

- Moina hutchinsoni Brehm, 1937

- Moina juanae Brehm, 1948

- Moina kazsabi Forró, 1988

- Moina lipini Smirnov, 1976

- Moina longicollis Jurine, 1820

- Moina macrocopa (Straus, 1820) (Japanese waterflea)

- Moina micrura Kurz, 1875

- Moina minuta Hansen, 1899

- Moina mongolica Daday, 1901

- Moina mukhamedievi Mirabdullaev, 1998

- Moina oryzae Hudec, 1987

- Moina pectinata Gauthier, 1954

- Moina propinqua G.O. Sars, 1885

- Moina reticulata (Daday, 1905)

- Moina rostrata McNair, 1980

- Moina ruttneri Brehm, 1938

- Moina salina Daday, 1888

- Moina tenuicornis G.O. Sars, 1896

- Moina weismanni Ishikawa, 1896

- Moina wierzejskii Richard, 1895

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Moina". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ "Moina". Australian Faunal Directory. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. October 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "Moinidae". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- ^ Geological and Natural History Survey of Minnesota (1884). Annual Report: Geological and Natural History Survey of Minnesota.

- ^ BOLD Systems: Moina {genus} - Arthropoda; Branchiopoda; Diplostraca; Moinidae;

- ^ Vignatti, Alicia María; Cabrera, Gabriela Cecilia; Echaniz, Santiago Andrés (2013). "Distribution and biological aspects of the introduced species Moina macrocopa (Straus, 1820) (Crustacea, Cladocera) in the semi-arid central region of Argentina". Biota Neotropica. 13 (3): 86–92. doi:10.1590/S1676-06032013000300011.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan (2008). "Makgadikgadi". The Megalithic Portal.

- ^ Makino, Wataru; Machida, Ryuji J.; Okitsu, Jiro; Usio, Nisikawa (2020-02-01). "Underestimated species diversity and hidden habitat preference in Moina (Crustacea, Cladocera) revealed by integrative taxonomy". Hydrobiologia. 847 (3): 857–878. doi:10.1007/s10750-019-04147-3. S2CID 209332097.

- ^ Bekker, Eugeniya I.; Karabanov, Dmitry P.; Galimov, Yan R.; Kotov, Alexey A. (2016-08-24). "DNA Barcoding Reveals High Cryptic Diversity in the North Eurasian Moina Species (Crustacea: Cladocera)". PLOS ONE. 11 (8) e0161737. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1161737B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161737. PMC 4996527. PMID 27556403.

- ^ Ni, Yijun; Ma, Xiaolin; Hu, Wei; Blair, David; Yin, Mingbo (2019-05-01). "New lineages and old species: Lineage diversity and regional distribution of Moina (Crustacea: Cladocera) in China". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 134: 87–98. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2019.02.007. PMID 30753887. S2CID 73443721.

- ^ Kotov, Alexey A.; Karabanov, Dmitry P.; Van Damme, Kay (2022-09-09). "Non-Indigenous Cladocera (Crustacea: Branchiopoda): From a Few Notorious Cases to a Potential Global Faunal Mixing in Aquatic Ecosystems". Water. 14 (18): 2806. doi:10.3390/w14182806.

Moina

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy

Classification

The genus Moina is classified within the kingdom Animalia, phylum Arthropoda, class Branchiopoda, superorder Diplostraca, order Anomopoda, family Moinidae.[3] The genus was established by William Baird in 1850 in his work The Natural History of the British Entomostraca, where he initially placed it within the group Cladocera based on its branchiopod morphology.[3] Baird's description highlighted Moina as a distinct genus of small entomostracans characterized by their bivalved carapace and antennal locomotion. The type species of Moina is Moina brachiata (Jurine, 1820), designated as the name-bearing type under the principles of zoological nomenclature, which fixes the application of the genus name to this species and its relatives.[7] The family Moinidae comprises small-bodied cladocerans, typically measuring 0.5–2 mm in length, that are distinguished from the closely related family Daphniidae primarily by differences in setation patterns on the second antennae and trunk limbs, as well as the presence of an ocellus in some moinids and specific postabdominal structures. These features include heavy setation on the exopod of the second antenna extending from the second to fourth segments and a characteristic two-pointed tooth on the posterior angle of the postabdomen.[8] Moinidae represents the sister group to Daphniidae within Anomopoda, sharing a common ancestry but diverging in appendage morphology adapted to diverse aquatic niches.Phylogenetic position

Moina is placed within the order Anomopoda of the subclass Cladocera, specifically in the family Moinidae, which forms a sister group to the Daphniidae based on morphological and molecular phylogenetic analyses. The divergence of Moinidae from other anomopod lineages is estimated to have occurred during the Mesozoic era, supported by fossil records of anomopod ephippia dating to the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary in regions such as Mongolia. Molecular evidence from cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene sequencing has delineated two primary genetic lineages in Moina across Eurasia: the European-Western Siberian lineage and the Eastern Siberian-Far Eastern lineage, with a transitional zone near the Yenisey River basin. These lineages reflect deep evolutionary splits, highlighting the genus's biogeographic structuring. While 28S rRNA has been used in broader cladoceran phylogenies, COI barcoding has been pivotal for resolving intraspecific relationships in Moina. Recent molecular studies have uncovered extensive cryptic diversity within Moina, with 21 phylogroups identified in Northern Eurasia through analysis of over 300 COI sequences, encompassing complexes like brachiata-like, micrura-like, macrocopa-like, and salina-like clades. In Japan, investigations have revealed seven species-level lineages, contributing to the recognition of previously undetected diversity in East Asia.[9] In China, COI-based analyses have identified 11 lineages across four species complexes, with five restricted to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, underscoring regional endemism and hidden speciation. In 2025, a new species, Moina heilongjiangensis, was described from a brackish lake in northeast China, further highlighting cryptic diversity in the genus.[6] This cryptic diversity suggests that the accepted taxonomy underestimates the true number of evolutionary independent units in the genus. At least four Moina species, including M. macrocopa, have become established outside their native ranges, often in eutrophic or temporary waters across the Americas, Africa, and Australia, facilitated by human activities such as aquaculture and waterfowl transport. Genetic markers, particularly COI barcodes, enable tracking of these invasions by distinguishing invasive lineages from native ones and revealing multiple introduction events, as seen in M. macrocopa populations in Argentina and South America.[10]Description

Morphology

Moina species exhibit a typical cladoceran body plan, characterized by a transparent, bivalved carapace that encloses the trunk and much of the abdomen, leaving the head and postabdomen partially exposed. The body is generally small, ranging from 0.5 to 2 mm in length, with an elongated, somewhat discus-shaped form that facilitates filter-feeding and locomotion in aquatic environments. The head is dome-shaped and narrowed, featuring a distinct supraocular depression and a shorter rostrum compared to related genera like Daphnia; it bears a single compound eye, often without an ocellus in many species, and long antennules that serve chemosensory functions.[11][8] Locomotion is primarily driven by the second antennae, which are large, biramous appendages with a four-segmented ventral branch bearing four terminal filaments and branched setae, enabling the characteristic jerky swimming motion of cladocerans. The trunk houses five pairs of thoracic limbs, which are phyllopodous and equipped with setae for particle capture during filter-feeding; these limbs beat rhythmically to generate water currents. The postabdomen is elongated, terminating in a pair of long, stout claws armed with teeth, used for grooming and anchoring.[11][8] Internally, Moina possess a specialized filter-feeding apparatus where the thoracic limbs' setae trap algal particles, directing them to the mouth via mandibular and maxillary structures. The digestive system includes a foregut for ingestion, a midgut for nutrient absorption tailored to phytoplankton diets, and a hindgut for waste expulsion, with the heart located dorsally in the thorax to support efficient circulation.[11] Sexual dimorphism is pronounced, with males typically smaller (0.6–0.9 mm) than females (1–2 mm) and featuring modified antennules for clasping during mating, as well as a copulatory hook on the first thoracic limb. Across the genus, morphological variations include slight differences in carapace ornamentation and appendage setation, though core traits like the postabdominal claws and antennal structure remain diagnostic. Larger sizes in certain lineages may correlate with genetic diversity, but anatomical features are broadly consistent.[1][11]Genetic diversity

Genetic studies of the genus Moina have revealed substantial cryptic speciation, where morphologically indistinguishable populations exhibit significant genetic divergence. Analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), particularly the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene, has identified numerous undescribed phylogroups across various regions. For instance, in northern Eurasia, 21 distinct phylogroups were delineated from 317 COI sequences, with genetic divergences ranging from 3.9% to 28.1%, indicating a level of hidden diversity comparable to that in the more extensively studied genus Daphnia.[5] In Asian populations, such as those in China, mtDNA sequencing uncovered 11 lineages within four morphological species complexes, including five previously unreported ones, despite conserved external morphology; these lineages often show paraphyly and discordance with nuclear markers like ITS-1, suggesting ongoing hybridization or introgression. A new species, Moina heilongjiangensis, was described in 2025 from a brackish lake in northeast China, further illustrating the genus's cryptic diversity.[6] This cryptic diversity underscores the genetic basis for adaptive traits in Moina species, particularly tolerance to environmental stressors like salinity. In Moina brachiata, populations from temporary ponds in the Hungarian Great Plain display four cryptic lineages structured by habitat salinity and depth, with one lineage strongly associated with shallower, more saline waters influenced by evaporation and hydroperiod variations; this divergence likely reflects selection on alleles enabling osmotic regulation and desiccation resistance.[12] Such genetic partitioning highlights how intraspecific variation facilitates adaptation to fluctuating aquatic conditions, though specific stress-response genes (e.g., those involved in ion transport or antioxidant pathways) remain underexplored in Moina compared to related cladocerans. Population genetics within Moina reveals contrasting patterns of gene flow depending on species distribution. Cosmopolitan taxa like Moina micrura exhibit moderate connectivity within continental regions, such as Eurasia, where some phylogroups span large areas (e.g., from Europe to the Far East), implying ongoing dispersal via waterfowl or human activities; however, intercontinental barriers limit gene flow, as evidenced by deep mtDNA divergence (~8%) between European and Australian populations, rendering the latter a distinct lineage.[13][5] In contrast, endemic species like Moina australiensis, restricted to Australian freshwater systems, show pronounced genetic isolation, with no evidence of gene exchange with Old World counterparts, promoting localized adaptation but increasing vulnerability to habitat loss.[13] Key research has refined our understanding of Moina diversity, with recent studies estimating around 10–11 valid species (as of 2025) alongside multiple cryptic lineages, which has direct implications for conservation. A comprehensive DNA barcoding study across northern Eurasia not only confirmed high endemism (e.g., several phylogroups confined to the Eastern Siberian-Far Eastern zone) but also highlighted risks from anthropogenic introductions that could hybridize native lineages, necessitating targeted protection of regional ponds and wetlands.[5] Similarly, Oriental region surveys emphasize the role of molecular tools in resolving taxonomy, as morphological criteria alone underestimate biodiversity and overlook evolutionary units critical for ecosystem resilience.Habitat and distribution

Preferred environments

Moina species thrive in a variety of dynamic and often harsh aquatic environments, particularly those characterized by fluctuating conditions. They are commonly found in temporary ponds, saline lakes, and eutrophic waters, where they can rapidly exploit short-lived opportunities for growth and reproduction.[2][11] These habitats often feature high levels of organic matter and nutrients, supporting dense algal blooms that serve as a primary food source, though Moina's presence is more tied to the overall environmental instability than to specific biotic factors.[14] A key adaptation enabling Moina to occupy ephemeral habitats is their tolerance to extreme abiotic conditions. They can endure low dissolved oxygen levels down to 0.5 mg/L, shifting metabolic pathways to anaerobic processes under hypoxia, which allows survival in oxygen-depleted, polluted, or stagnant waters.[14] Salinity tolerance varies by species but extends up to 70 ppt in some, such as Moina mongolica, facilitating colonization of brackish and hypersaline lakes, while others like Moina macrocopa are limited to below 8 ppt.[15] Temperature ranges from 5°C to 32°C are generally tolerated (with short-term tolerance up to 37°C), with optimal growth between 24°C and 31°C, enabling persistence across seasonal variations in temporary pools.[2] Additionally, Moina prefer water with a neutral to alkaline pH of 7 to 9, aligning with the chemistry of nutrient-enriched, often sewage-influenced systems.[16] The production of ephippial eggs is crucial for Moina's success in drying or intermittent habitats, as these drought-resistant resting stages can withstand prolonged desiccation—up to eight months in some cases—before hatching upon rehydration, allowing rapid recolonization of refilled ponds.[17] In terms of microhabitat use, Moina are primarily planktonic in open water columns of larger temporary or eutrophic bodies, where they filter-feed efficiently, but they may shift to benthic or near-substrate positions in shallow, vegetated margins during low-water periods to avoid desiccation or predation.[11] This behavioral flexibility enhances their resilience in unstable environments dominated by high nutrient inputs and variable hydrology.[18]Global range

The genus Moina exhibits a cosmopolitan distribution across freshwater and brackish water bodies worldwide, with native populations most prominent in Eurasia, Africa, and Australia. In Eurasia, species are widespread from Europe through Siberia and into Asia, including extensive records in China and the Middle East, often dominating zooplankton communities in temporary ponds and rice fields. African occurrences include North African regions and West African sites such as Nigeria, where Moina species contribute to local aquatic ecosystems. In Australia, native halophilic taxa thrive in salt lakes of the central arid zones. Recent discoveries as of 2025, such as the euryhaline Moina heilongjiangensis in brackish waters of northeastern China, highlight ongoing expansion of known diversity in Asian habitats.[19][1][20][21][6] Introduced populations of Moina have expanded globally through human-mediated dispersal, particularly via aquaculture for use as live feed in fish farming. Moina macrocopa, for example, has established in North America and parts of Asia beyond its native range, while Moina micrura appears rarely in the Great Lakes region, with isolated records from Lake Michigan near Green Bay. In South America, M. macrocopa was first documented in Bolivia in 1994 and subsequently in northeastern Argentina by 1997, linked to anthropogenic water bodies like reservoirs and wastewater ponds. These introductions reflect broader patterns of spread in over 50 countries, facilitated by the genus's tolerance for varied conditions and its utility in tropical and subtropical aquaculture systems.[1][22] Biogeographically, Moina shows Holarctic dominance, with core native ranges in temperate Eurasia extending into tropical and subtropical zones through both natural dispersal and human activity; endemics like Moina baylyi highlight regional specialization in Australian hypersaline environments. Genetic studies reveal cryptic diversity supporting this pattern, with distinct lineages in Palearctic, Afrotropical, and Australasian realms.[23][24][5]Reproduction and life cycle

Parthenogenetic reproduction

Parthenogenetic reproduction is the primary mode of asexual propagation in the genus Moina, enabling rapid clonal expansion under favorable environmental conditions. Females produce diploid eggs through ameiotic parthenogenesis, a process in which oocytes undergo a modified meiosis that suppresses reduction division, resulting in unreduced diploid embryos without fertilization. These eggs are brooded internally within the marsupium, a ventral brood pouch formed by the carapace, where they develop for approximately 3-5 days before release as juveniles.[25][26] This reproductive strategy is triggered by optimal conditions such as high food availability and low population density, which favor the production of all-female broods and suppress the transition to sexual reproduction. At 25°C, Moina generations typically cycle every 4-7 days, supporting population growth rates of up to 0.5 per day, as observed in species like Moina macrocopa. The developmental stages commence with egg formation in the ovary, followed by transfer to the marsupium for incubation; upon hatching, neonates are released as miniature versions of adults, measuring about 0.34 mm in length and immediately resembling mature females in morphology, though smaller in size.[25][27] The advantages of parthenogenesis in Moina include explosive population proliferation in transient or resource-rich habitats, where all-female offspring allow a single colonist to rapidly establish a large clonal population. This mode facilitates quick exploitation of temporary water bodies, enhancing survival and dispersal in unpredictable environments characteristic of cladocerans.[25]Sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction in Moina represents a stress-induced phase in its cyclical parthenogenetic life cycle, triggered by environmental stressors including high population density (crowding), food scarcity, or temperature fluctuations, which prompt parthenogenetic females to produce male offspring and mictic females.[28][2][29] Males typically comprise a small proportion (around 10%) of the population under these conditions, sufficient to facilitate mating.[25] This shift contrasts with the parthenogenetic mode by enabling the production of genetically diverse, dormant propagules suited to survive adverse periods. Mating occurs when males use their modified antennules, armed with hooks, to grasp mictic females and transfer sperm, fertilizing haploid eggs to form diapausing ephippia—resting eggs highly resistant to desiccation, freezing, and other harsh conditions.[11][30][31] If fertilized, these eggs develop within a tough, chitinous dorsal case (ephippium) that incorporates part of the female's exoskeleton, typically enclosing 1-2 eggs.[18] Ephippia enter a state of dormancy lasting from months to several years, allowing Moina populations to persist through unfavorable periods such as drought or winter.[32][33] Hatching resumes upon rehydration and exposure to favorable cues, including optimal temperatures (around 20-25°C) and photoperiods, releasing amictic embryos that develop into active juveniles.[34] This sexual phase promotes genetic recombination during meiosis, generating novel allelic combinations that enhance genetic diversity and enable Moina populations to adapt to variable and unpredictable habitats.[35][36] Without periodic sexual reproduction, clonal propagation alone would lead to reduced variability and increased vulnerability to environmental changes or pathogens.[37]Ecology

Feeding habits

Moina species are filter feeders that primarily consume microalgae such as Chlorella vulgaris and Scenedesmus spp., along with bacteria, yeast, and detritus in the form of decaying organic matter.[2][14] These organisms filter suspended particles ranging from 1 to 50 μm in size directly from the water column, enabling efficient exploitation of microbial and phytoplankton resources in nutrient-rich environments.[18][14] The feeding mechanism relies on rhythmic beating of the thoracic limbs, which generate water currents that draw particles toward the mouth region.[18] Specialized setae on the endites of these limbs act as filters, trapping food particles that are then transported to the mouth for ingestion.[11] This process allows for continuous grazing without active pursuit of prey. Moina exhibits high grazing efficiency, with clearance rates reaching up to 0.315 mL per individual per hour on preferred food sources, contributing to the control of algal populations in pond systems.[38] Under optimal conditions, this filtration capacity helps mitigate excessive algal growth by removing substantial volumes of suspended matter.[2] Selective feeding is evident in Moina's preference for green algae like Monoraphidium contortum over cyanobacteria such as Microcystis spp., where clearance rates on the latter can drop below 0.1 mL per individual per hour due to toxicity or poor nutritional quality.[38] In response to starvation or low food concentrations, filtration and ingestion rates decrease, serving as an adaptive mechanism to conserve energy and trigger shifts in reproductive strategies.[39][40]Role in ecosystems

Moina species occupy the trophic level of primary consumers in aquatic food webs, primarily feeding on phytoplankton and detritus while serving as a crucial link to higher trophic levels. As filter feeders, they efficiently transfer energy from primary producers to predators such as fish larvae, amphibians, and various invertebrates, thereby supporting secondary production in freshwater ecosystems.[41][42][43] This role is particularly evident in their use as live feed for fish fry, where Moina's nutritional profile enhances larval growth and survival.[2] In ephemeral pools, they also fall prey to macroinvertebrate predators and amphibians, influencing community structure through these interactions.[44] Population dynamics of Moina exhibit characteristic boom-bust cycles, especially in temporary ponds where rapid reproduction leads to population peaks followed by declines due to resource depletion or drying. These cycles are facilitated by parthenogenetic reproduction under favorable conditions, allowing explosive growth.[20] Ephippia, the dormant resting eggs produced during unfavorable periods, function as seed banks in sediments, enabling recolonization when ponds refill after drought.[45] This dormancy strategy ensures persistence in intermittent habitats, contributing to the resilience of aquatic communities.[46] Moina provides key ecosystem services through nutrient recycling, excreting bioavailable forms of nitrogen (such as ammonia) and phosphorus (such as phosphate) that stimulate phytoplankton growth and maintain nutrient cycling in freshwater systems.[47] Their sensitivity to pollutants positions them as indicators of water quality, with population declines signaling contamination from heavy metals, cyanotoxins, or sewage.[48][49] In terms of biotic interactions, Moina competes with other cladocerans like Daphnia in shared habitats, where outcomes depend on factors such as ammonia levels or algal composition, often favoring Daphnia under toxic conditions.[50][51] Their grazing exerts predation pressure on algal communities, controlling bloom formation and promoting diversity by selectively consuming phytoplankton, including large colonies in wastewater systems.[52][53] This top-down control helps regulate primary production and prevents dominance by harmful algae.[54]Human uses

Aquaculture applications

Moina species, particularly M. macrocopa and M. micrura, serve as valuable live feeds in aquaculture due to their high nutritional content and suitability for larval and fry stages of various fish species. With a protein content averaging 50% of dry weight and fat levels of 4–27% depending on life stage, Moina provides essential amino acids and lipids that support rapid growth in fry of freshwater species such as tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), carp (Cyprinus carpio), and ornamental fish like angelfish (Pterophyllum scalare). Their small size—adults at 0.7–1.5 mm and juveniles under 0.4 mm—matches the mouth gape of newly hatched fry, making them more accessible than larger feeds, and they outperform brine shrimp (Artemia) in freshwater systems where the latter exhibit high mortality.[2][18][55] Cultivation of Moina typically employs batch or semi-continuous systems in tanks ranging from 38 L (10-gallon aquaria) for small-scale operations to 100–1000 L vats or ponds up to 1 m deep for commercial production, maintained at 23–28°C and pH 7.5–8.5. Recent studies as of 2025 have explored sustainable methods using wastewater from tilapia biofloc systems to culture M. macrocopa, promoting resource recycling.[56] Inoculation starts with neonates at densities of 1000–6000 individuals per liter, fed suspensions of baker's yeast (0.3–0.5 g per 100 L initially, increasing over time), microalgae like Chlorella (4×10^6 cells/mL), or organic fertilizers such as chicken manure (5–20 g per 100 L) to promote bacterial and algal blooms. Water quality is monitored for dissolved oxygen above 3 mg/L, with partial renewals of 20–50% every few days; cultures peak in 4–7 days, allowing harvest via netting or sieving through 50–150 µm mesh every 7–10 days, yielding populations up to 109,000 individuals/L under optimized diets like yeast combined with Haematococcus pluvialis. Enrichment with emulsions of fish oil or defatted algal meals further boosts highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFA) to 40% and carotenoids, enhancing feed quality without altering basic protocols.[2][18][57] Compared to Daphnia species, Moina offers advantages including faster reproduction rates (maturity in 4–5 days versus 7–10), greater tolerance to low oxygen (down to 1 mg/L) and high organic loads, and higher achievable densities (up to 5000/L versus 500/L), resulting in superior biomass yields of 106–110 g dry weight per m³ per day under yeast-based feeding, or up to 375 g/m³/day with phytoplankton and manure. These traits enable cost-effective production in resource-limited settings, reducing reliance on more sensitive alternatives.[2][18][57] Globally, Moina is widely adopted in Asian aquaculture, such as in China for carp and shrimp (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) larviculture, and in Singapore for ornamental fish with survival rates of 95–99%, while in Africa, introduced strains like M. macrocopa dominate feeds for Nile tilapia and African catfish in semi-open pond systems, supporting sustainable fry production amid growing demand.[18][2][58]Research applications

Moina species are employed as model organisms in various biological and environmental research fields due to their rapid reproduction, sensitivity to stressors, and cyclical parthenogenetic life cycle, which facilitates controlled laboratory studies. These attributes make them particularly valuable for investigating ecological impacts and physiological responses in aquatic systems. In ecotoxicology, Moina is frequently used to evaluate the toxicity of environmental pollutants, including heavy metals and pesticides, providing insights into their effects on freshwater invertebrates. For instance, acute toxicity tests on Moina micrura have shown differential sensitivity to heavy metals following the order Hg > Cu > Cd > Zn > Cr.[59] Similarly, exposure experiments with pesticides commonly used in agriculture, such as chlorpyrifos (LC50: 0.00008 mg/L), carbofuran (0.00696 mg/L), malathion (0.01044 mg/L), neem extract (0.1963 mg/L), and glyphosate (3.043 mg/L), demonstrate M. micrura's role in ranking toxicity levels and informing regulatory guidelines for paddy field runoff.[60] These studies underscore Moina's position as a standard test organism in standardized protocols like those from the OECD for aquatic hazard assessment. Developmental biology research leverages Moina's parthenogenetic reproduction to explore genetic mechanisms underlying asexual and sexual transitions, as well as dormancy processes. Investigations into parthenogenesis genetics have identified transcriptional responses to environmental cues in Moina macrocopa, revealing key genes involved in stress perception and reproductive mode switching, which contribute to rapid population adaptation.[61] Ephippial dormancy, the resistant stage formed during sexual reproduction, has been studied through experiments on hatching triggers; for example, in M. micrura, ephippia hatching rates increase under specific photoperiods (12:12 light:dark) and light intensities (around 5000 lux), while food density influences ephippia production and male induction, aiding understanding of diapause regulation.[34][28] Such work establishes Moina as a tractable system for dissecting the molecular basis of cyclical parthenogenesis. In climate change modeling, Moina's tolerance to abiotic stressors like salinity and temperature is examined to predict responses to habitat alterations, such as salinization from rising sea levels or drought. Laboratory experiments simulating increased salinity show that M. macrocopa maintains viable populations up to 8 ppt but experiences reduced growth and reproduction at higher levels (e.g., 12-16 ppt), correlating with projected habitat loss in temporary ponds.[62] Temperature-salinity interactions further reveal thresholds where survival declines, as in studies where combined warming and salinization halved population densities, informing ecological forecasts for cladoceran communities under global change scenarios.[20] Historical research on Moina traces back to the late 19th century, with August Weismann's studies in the 1870s on cladoceran life cycles, including observations of parthenogenetic and sexual phases in species like Moina, laying foundational insights into alternation of generations.[63] Modern extensions include emerging applications of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in related cladocerans like Daphnia, which demonstrate efficient targeted mutagenesis and hold promise for functional genomics in Moina due to shared reproductive amenability.[64]Species

Accepted species

The genus Moina Baird, 1850, encompasses 18 accepted species according to the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS), though molecular studies indicate potential cryptic diversity and ongoing taxonomic revisions that may adjust this number to 15–25 valid taxa. These species are primarily found in freshwater and occasionally brackish environments, often in temporary or eutrophic waters, with distributions spanning cosmopolitan to regional patterns. Validity is determined based on morphological and genetic criteria from authoritative databases like ITIS and the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), excluding synonyms such as Moina weirzejskii Richard, 1895 (now a synonym of M. macrocopa). Recent additions include Moina heilongjiangensis Kotov & Sinev, 2025, described from brackish lakes in northeast China. The accepted species, with authorities and years, are listed below, along with brief characterizations of key traits, habitats, and distributions for representative examples:- Moina affinis Birge, 1893

- Moina australiensis G.O. Sars, 1896: Australian endemic, typically in freshwater ponds and temporary waters; body length up to 1.5 mm.

- Moina belli Gurney, 1904

- Moina brachiata (Jurine, 1820): The type species of the genus, primarily Eurasian with a Palearctic distribution; inhabits temporary and semi-permanent ponds, tolerating varying salinities; adult size 0.8–1.2 mm.[65][12]

- Moina brachycephala Goulden, 1968

- Moina flexuosa Sars, 1897

- Moina hartwigi Welter, 1898

- Moina hutchinsoni Brehm, 1937

- Moina macrocopa (Straus, 1820): Cosmopolitan, widespread in nutrient-rich, eutrophic waters including ponds, lakes, and wastewater environments; highly tolerant of pollution and temporary habitats; adult size 0.7–2.0 mm.[66][67]

- Moina micrura Kurz, 1875: Often in brackish and estuarine waters, considered invasive in some regions; prefers temporary ponds with organic decomposition in tropical/subtropical areas, though true M. micrura s.s. is restricted to parts of Europe, Middle East, and Asia; adult size 0.6–1.2 mm.[68][24]

- Moina minuta Hansen, 1899

- Moina mongolica Daday, 1901

- Moina reticulata Daday, 1905

- Moina salina Daday, 1888: Halophilic, in saline lakes and ponds, particularly in arid regions.

- Moina tenuicornis Sars, 1896

- Moina weismanni Ishikawa, 1897

- Moina wierzejskii Richard, 1895 (accepted in ITIS, but synonymized with M. macrocopa in some recent works)

- Moina heilongjiangensis Kotov & Sinev, 2025: Recently described from brackish soda lakes in Heilongjiang Province, China; euryhaline, unable to survive in pure freshwater; adult size ~1.2 mm.[6]