Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mohéli

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2020) |

Mohéli [mɔ.e.li], also known as Mwali,[2] is an autonomously-governed island that forms part of the Union of the Comoros. It is the smallest[3] of the three major islands in the country. It is located in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Africa and it is the smallest of the four major Comoro Islands.[4] Its capital and largest city is Fomboni.[5]

Key Information

History

[edit]

Until 1830, Mohéli was part of the Ndzuwani Sultanate, which also controlled the neighbouring island of Anjouan. In 1830, migrants from Madagascar led by Ramanetaka, who later changed his name to Abderemane, took over the island and established the sultanate of Mwali. Its ruler was Queen Jumbe-Souli in the mid-nineteenth century. In 1886, France made the island a protectorate.

Until 1889, Mwali had its own French resident, but the island was then subjugated to the residency of Anjouan. The sultanate was dismantled in 1909 following the French annexation of the island. French colonial stamps bearing the inscription "Mohéli" were circulated between 1906 and 1912.

Comoros

[edit]In 1975, Mohéli agreed to join the Comoros nation, along with Grande Comore and Anjouan. Political, economic and social turmoil affected Mohéli and the Comoros in general.

Independence

[edit]On 11 August 1997, Mohéli seceded from the Comoros, a week after Anjouan. Mohéli's secessionist leaders were Said Mohamed Soefu, who became president, and Soidri Ahmed, who became prime minister.

Rejoining Comoros

[edit]Mohéli rejoined Comoros in 1998. In 2002, Mohéli ratified the new Comorian constitution, which provided for a less centralized federal government and more power to the island governments. It helped settle the continuing political turmoil in Comoros and the continuing secessionism on Anjouan. The same year, Mohamed Said Fazul was elected president. His supporters won most seats in Mohéli's delegation to Parliament in the legislative elections of 2004.

Politics

[edit]Mohamed Said Fazul was elected president of Mohéli in 2002 against Mohamed Hassanaly.

The legislative assembly of the autonomous island of Moheli has ten seats and was elected on 14 and 21 March 2004. Nine seats were won by the supporters of Said Mohamed Fazul, and the last by a supporter of Azali Assoumani. In 2007, Mohamed Ali Said was elected president of the autonomous island of Moheli (currently president instead of governor) against Said Mohamed Fazul.

After shortening his two-year term, which was to end in 2012, due to problems with the electoral calendar, Mohamed Ali Said was re-elected governor of the autonomous island of Moheli in December 2010 against the presidential majority candidate Said Ali Hilali. The election of the island's councillors was won by an absolute majority by Mohamed Ali Said's camp.

Following the legislative and communal elections held in 2015, it was Governor Mohamed Ali Said's party that won the majority in the island assembly, allying with the councillors (equivalent to deputies at the national level) of those of President Ikililou's supporters and related parties (UPDC party).

In May 2016, following the island governors' elections, it was Mohamed Said Fazul who won against President Ikililou's wife (Hadidja Dhoinine) in the 5-year governorship elections. It is therefore the second time he takes the reins of the island of Moheli.

As a reminder, at the national level, it is the former president (2002-2006) Azali Assoumani who won the elections before Mohamed Ali Soilih. This is his second term (2016-2021) as President of the Union of the Comoros.

Population

[edit]Mohéli's population, as of 2006[update], is about 38,000. Its main ethnic group, as on the other Comoros islands Grande Comore and Anjouan as well as the French territory Mayotte, is the Comorian ethnic group, a synthesis of Bantu, Arab, Malay and Malagasy culture. The main religion is Sunni Islam.

Communities

[edit]- Fomboni - 19,000

- Nioumachoua - 3,400

- Wanani - 2,500

- Djoièzi - 1,636

Environment

[edit]

Protected areas

[edit]On 19 April 2001, the first protected area in this country – Mohéli Marine Park – was gazetted.[6] This was the culmination of a unique process by which the local communities in the ten villages around the park boundaries negotiated a collaborative arrangement with the government for the establishment and management of the park. The marine park programme was among the 27 finalists selected from nearly 500 nominations by the Equator Initiative, a partnership between the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), IUCN, the UN Foundation and four other international groups, to promote community-based initiatives aimed at furthering sustainable development. The marine park was redesignated Mohéli National Park in 2010, and in 2015 was expanded to include approximately three-quarters of the island's land area.[7]

Important Bird Area

[edit]A 6,268 ha tract encompassing the highlands of the interior of the western part of the island, including Mount Mlédjélé, has been designated an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports populations of Comoro olive pigeons, Comoro blue pigeons, tropical shearwaters, Moheli scops owls, Malagasy harriers, Moheli brush warblers, Moheli bulbuls, Comoro thrushes, Humblot's sunbirds and red-headed fodies.[8]

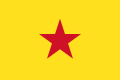

Flags

[edit]Airport

[edit]Mohéli Bandar Es Eslam Airport, between the villages of Fomboni and Djoièzi on the north coast of the island is the only airport on Mohéli.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Information : Arrêté du gouvernorat de l'île autonome de Mohéli". La France en Union des Comores.

- ^ "Figure 1. Map of the Comoros showing the islands of Ngazidja (Grande..." ResearchGate. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- ^ Verhandelingen der Koninklijke Nederlandsche Akademie van Wetenschappen te Amsterdam, Afdeeling Natuurkunde: Tweede sectie. N.V. Noord-Hollandsche Uitgevers-Maatschappij. 1938.

- ^ Frazier, J. (1985). Marine Turtles in the Comoro Archipelago. North-Holland Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-444-85629-6.

- ^ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica: Micropaedia. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1995. ISBN 978-0-85229-605-9.

- ^ Hauzer, Melissa D. (2007). Stakeholders' Perceptions of Mohéli Marine Park, Comoros: Lessons Learned from Five Years of Co-management. Community Centred Conservation (C3).

- ^ UNEP-WCMC (2021). Protected Area Profile for Parc National de Mohéli from the World Database of Protected Areas. Accessed 10 August 2021. [1]

- ^ "Mont Mlédjélé (Mwali highlands)". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

Mohéli

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Topography

Mohéli, also known as Mwali, constitutes the smallest island in the Union of the Comoros archipelago, situated in the western Indian Ocean between northeastern Mozambique and northwestern Madagascar. The island's central coordinates are approximately 12°20′S latitude and 43°45′E longitude, positioning it as the southeasternmost major island in the chain. Covering an area of 290 km², Mohéli forms part of the volcanic Comoros islands, which align along a northwest-southeast trend originating from the East African Rift system.[7][8] Geologically, Mohéli originated from Pliocene-to-Pleistocene volcanic activity along a northwest-southeast rift zone, resulting in an extinct volcanic edifice without recent eruptions. The island's topography is characterized by a relatively flat central plateau averaging 300 meters in elevation, flanked by low mountains and hills, with the highest peak, Mount Mze Koukoulé, reaching 790 meters. This contrasts with the steeper, more dissected terrains of neighboring islands like Grande Comore, owing to Mohéli's smaller size and older, eroded volcanic structure.[9][10] Coastal features include narrow plains transitioning to mangrove-lined shores and fringing coral reefs, while inland soils comprise fertile yet porous volcanic andesitic compositions that limit surface water accumulation. Permanent rivers are scarce due to rapid groundwater percolation, but shallow lagoons and seasonal streams support localized hydrology, distinguishing Mohéli's subdued relief from the higher, wetter profiles of adjacent islands.[11][12]Climate and Natural Resources

Mohéli possesses a tropical maritime climate, with average annual temperatures ranging from 24°C to 30°C and little diurnal or seasonal variation beyond minor influences from trade winds. Minimum temperatures occasionally dip to 22°C during the cooler months of July and August, while daytime highs typically reach 28-32°C year-round.[13][14] Precipitation follows a bimodal pattern, with the primary rainy season spanning November to April, delivering heavy downpours driven by northeast monsoon winds, often exceeding 2,000 mm annually in elevated areas. The secondary dry season from May to October features reduced rainfall, averaging under 100 mm per month, though brief showers persist. The island remains vulnerable to tropical cyclones during the wet period, with historical events linked to intensified storms in the Mozambique Channel.[15][15] Volcanic topography, including a central ridge rising to Mount Goui at 792 m, generates microclimatic variations, where orographic effects enhance rainfall in highlands—potentially up to 5,000 mm yearly—contrasted with drier coastal zones receiving around 1,000 mm. This elevational gradient supports diverse habitats, from mist-shrouded uplands to sun-exposed lowlands.[16][17] Natural resources include extensive forest cover, with natural forests comprising approximately 85% of Mohéli's land area (about 18,600 hectares) as of 2020, dominated by endemic species in lowland and montane zones. The surrounding exclusive economic zone contributes to fisheries potential, part of Comoros' broader 160,000 km² maritime domain estimated to sustain 33,000 metric tons of annual catch, primarily tuna and pelagic species. Mineral deposits remain limited, with no major exploitable reserves of pumice or salt documented specifically on the island, though volcanic geology suggests minor occurrences tied to ancient fissure activity.[18][19][20]History

Pre-Colonial and Early Sultanate Era

Mohéli's earliest known settlements date to the 8th century CE, when permanent villages were established by Arab seafarers traversing Indian Ocean trade routes from East Africa. These communities formed part of a broader pattern of human migration to the Comoros archipelago, involving Bantu-speaking peoples from mainland East Africa who arrived between the 6th and 8th centuries, intermingling with Arab traders and, to a lesser extent, Austronesian navigators whose influence traces back to earlier Southeast Asian seafaring.[21] Archaeological evidence from sites across the islands, including pottery and structural remains indicative of coastal trading posts, supports this timeline, though specific Mohéli artifacts remain sparse and primarily oral histories preserve details of initial Afro-Arab ethnogenesis.[21] Genetic analyses further corroborate a tripartite admixture, with African, Middle Eastern, and Southeast Asian ancestries reflecting sustained migratory influxes rather than isolated settlement.[22] Social organization emphasized matrilineal kinship, a system inherited from pre-Islamic Bantu substrates and resilient to later Arab-Persian influences, wherein descent, property inheritance, and residence followed maternal lines.[23] This structure fostered decentralized authority, with local lineages headed by matrilineal elders or notables rather than hierarchical kingship, enabling adaptive responses to environmental and trade pressures on the small island.[24] Early governance thus relied on consensus among clan heads, a pattern evident in oral traditions of dispute resolution through kinship alliances, which archaeological continuity in village layouts—clustered around matrilocal homesteads—suggests persisted from initial habitation phases.[21] By the 15th to 16th centuries, nascent sultanates emerged on Mohéli amid expanding Swahili-Arab trade networks, integrating the island into regional exchanges of spices, ivory, and slaves for mainland commodities like gold and rice.[25] Mohéli's rulers, often styling themselves as sultans under Islamic legitimacy, facilitated exports of locally procured slaves—sourced from raids or tribute—and imported ivory from Mozambique, though volumes remained modest compared to larger Comoros islands due to the island's limited population and resources.[25] Power remained fragmented among coastal notables controlling ports, with no evidence of island-wide centralization; this reliance on autonomous local elites, driven by trade's causal demands for flexibility over rigid control, prefigured enduring patterns of decentralized rule up to European sightings by Portuguese explorers in the early 16th century.[21]Colonial Period under France

In April 1886, Mohéli became a French protectorate when its ruler, Queen Salima Machamba, placed the island under French protection, marking the onset of formal colonial oversight.[26] This arrangement preserved nominal local authority under the sultanate while subordinating foreign affairs and defense to French residents. The protectorate status persisted until 1909, when French authorities dismantled the sultanate, annexed the island outright, and integrated it administratively with the other Comoros islands under a unified colonial framework.[26] French colonial stamps inscribed "Mohéli" were issued from 1906 to 1912 to facilitate postal services tied to the mainland administration.[27] Colonial economic policy emphasized plantation agriculture to supply export commodities, with French settlers and companies acquiring land for cultivation of cash crops such as ylang-ylang, vanilla, and copra.[1] These plantations occupied significant portions of arable land, displacing subsistence farming and traditional land use patterns while channeling labor toward export-oriented production.[28] Profits from these ventures primarily benefited French interests, with limited reinvestment in local development. Infrastructure remained rudimentary, consisting mainly of coastal ports like Fomboni and rudimentary roads designed to transport goods to export points rather than foster broad connectivity or public services.[29] From 1912 to 1946, Mohéli fell under the governance of the French administration in Madagascar, which prioritized resource extraction over comprehensive modernization.[30] Following World War II, the Comoros islands, including Mohéli, were reorganized as a distinct French overseas territory in 1946, granting limited autonomy while retaining metropolitan control over key policies.[29] This period saw modest population stabilization due to improved health measures and reduced intertribal conflicts, though economic dependencies entrenched vulnerabilities in food security and diversification.[1]Post-Independence Integration and Separatism

Upon the declaration of independence for the Comoros archipelago on July 6, 1975, under President Ahmed Abdallah, Mohéli was incorporated as one of the three principal islands in the newly formed federal Islamic Republic, adhering to the central authority in Moroni despite its peripheral economic status and limited infrastructure development.[31] Initial integration proceeded without overt resistance from Mohéli, but the island's small population of approximately 20,000 and reliance on subsistence agriculture and fishing exacerbated vulnerabilities to national-level fiscal imbalances, where revenues from vanilla exports and aid were disproportionately allocated to Grande Comore.[32] By the mid-1990s, systemic corruption, hyperinflation exceeding 50% annually, and unequal resource distribution under successive unstable regimes—marked by over 20 coups since independence—intensified local grievances on Mohéli, culminating in a unilateral declaration of independence on August 11, 1997, shortly after Anjouan's secession the prior month.[32][33] The move, led by Mohéli's self-proclaimed president Said Mohamed Soefu, was driven by causal factors including chronic poverty rates above 60%, neglect of island-specific needs like harbor maintenance, and perceptions of Moroni's extractive governance that funneled customs duties without reciprocal investment.[34] Foreign mercenaries, including figures linked to prior Comorian interventions, briefly bolstered separatist defenses amid threats of federal retaliation, though external actors like France provided tacit support for reunification to preserve regional stability.[32] The Organization of African Unity (OAU, predecessor to the African Union) facilitated mediated talks, yielding the Fomboni Declaration on February 17, 2001, signed in Mohéli's capital and committing parties to a reformed union with enhanced island autonomy, including control over local budgets and justice systems.[35] This paved the way for a December 2001 constitution establishing a confederated structure, with rotating four-year presidencies among the islands and revenue-sharing formulas allocating at least 50% of customs duties to autonomous governments, though implementation lagged due to persistent central oversight disputes.[31] A supplementary 2001-2002 reconciliation process, including AU military assistance to reintegrate Anjouan, extended fragile stability to Mohéli by 2003, reducing active separatist violence but leaving fiscal disparities unresolved, as Mohéli's per capita GDP remained under $800 amid national debt servicing absorbing over 20% of budgets.[34] Under President Azali Assoumani, who assumed power via coup in 1999 and was elected in 2016, Mohéli has experienced relative quiescence in separatist activities since 2006, bolstered by targeted infrastructure projects like road upgrades funded through Chinese loans exceeding $100 million and localized election pacts that preserved autonomy amid national referenda.[36] However, underlying tensions persist from uneven fiscal transfers—Mohéli receiving only about 15% of union revenues despite constitutional entitlements—and Assoumani's 2018 constitutional amendments extending term limits, which critics attribute to centralizing tendencies risking renewed island discontent without addressing root economic neglect.[37] This post-reintegration equilibrium reflects pragmatic local adaptation to federal constraints rather than full resolution of causal drivers like resource inequities.[38]Government and Politics

Administrative Framework within Comoros

Mohéli functions as one of three autonomous islands within the Union of the Comoros, a status formalized by the 2001 Constitution, which delineates powers between the federal Union government and the island administrations.[39] This framework grants Mohéli authority over internal affairs, including education, health, local infrastructure, and economic development, while reserving foreign policy, defense, and currency for the Union level.[40] The island's governance centers in Fomboni, its capital, where the island president—equivalent to a governor—and the Island Assembly exercise executive and legislative functions, respectively, elected for five-year terms by universal suffrage.[40] The presidency of the Union rotates among the autonomous islands of Grande Comore, Anjouan, and Mohéli every five years to ensure equitable representation, as stipulated in the Constitution.[39] Under this system, the Union president must hail from the designated island for that cycle, with vice presidents drawn from the other two islands to balance influence.[41] Mohéli's representatives have held the Union presidency in past rotations, such as Ikilou Dhoinine's term from 2011 to 2016.[41] Mohéli possesses fiscal autonomy to levy internal taxes and fees on goods, services, and local activities to fund island-level operations, supplementing federal allocations.[42] Island budgets derive from these revenues alongside proportionate transfers from the Union's shared resources, primarily customs duties and income taxes, enabling localized decision-making on expenditures like public services and development projects.[42] This decentralized revenue model supports Mohéli's administration in addressing island-specific priorities within the federal structure.[40]Separatist Movements and Autonomy Struggles

In 1997, amid escalating dissatisfaction with the Comoros Union's central governance, Mohéli declared secession on August 11, following Anjouan's move weeks earlier.[36] The primary drivers included the Union's repeated political upheavals—over 20 successful or attempted coups d'état since independence from France in 1975—and perceptions of federal mismanagement exacerbating economic disparities across islands.[43] [44] Secessionists argued that Mohéli's relative internal stability, contrasted with chaos on Grande Comore, justified separation to preserve local order and prevent resource siphoning to the federal capital.[32] Efforts to reintegrate Mohéli began after the 1999 coup by Colonel Azali Assoumani, culminating in the 2000 Fomboni Agreement and the 2001 constitution, which established a federal structure granting islands semi-autonomous status with elected presidents and assemblies handling internal affairs.[36] [45] However, post-reintegration demands persisted for enhanced fiscal federalism, as islands like Mohéli generated limited revenues yet contributed disproportionately to union obligations, fueling grievances over centralized control.[46] These tensions manifested in 2018 protests on Mohéli against a constitutional referendum perceived as enabling federal election manipulations and extending President Azali's tenure beyond rotational norms, highlighting ongoing critiques of overreach suppressing island self-determination.[47] While the autonomy framework enabled Mohéli to enact localized governance measures, including environmental protections aligned with its biodiversity focus, critics contend it falls short of addressing root causes like revenue retention and has not fully mitigated emigration pressures compared to more restive islands like Anjouan.[48] Outcomes include reduced localized violence post-2001 but persistent calls for devolution, as federal interventions have at times overridden island priorities, underscoring causal links between centralization and separatist sentiments rooted in empirical governance deficits.[32]Economy

Primary Economic Sectors

Agriculture remains the dominant sector in Mohéli's economy, employing the majority of the island's labor force in subsistence farming of crops such as cassava, rice, bananas, and coconuts, alongside cash crop production including ylang-ylang, cloves, and copra, which serve as key exports for the Comoros archipelago.[28][19] Copra production, derived from coconuts, constitutes a primary economic activity on Mohéli, supporting local processing and trade despite limited industrial capacity.[28] These activities contribute significantly to the island's output, mirroring Comoros-wide patterns where agriculture accounts for approximately 40-50% of GDP and sustains over 80% of employment.[49] Fishing, primarily artisanal, represents another foundational sector, with operations targeting species like tuna, grouper, and snapper in Mohéli's surrounding waters, which hold substantial marine resources including tuna stocks.[50] This sector provides livelihoods for coastal communities and contributes to food security, though it remains small-scale without extensive commercial development.[19] Emerging ecotourism, driven by the Mohéli Marine Park established in 2001, attracts visitors for coral reef and biodiversity viewing, generating revenue through limited accommodations and guided activities; a 1998 assessment valued associated reef tourism services at 1.3% of Comoros GDP, underscoring potential despite low visitor volumes.[51] Remittances from the Comorian diaspora, estimated at around 13% of national GDP over the past decade, supplement household incomes on Mohéli, funding consumption and small investments amid minimal manufacturing or large-scale trade.[16] Overall, Mohéli's per capita GDP lags the Comoros average due to geographic isolation, with national figures approximating $1,600 PPP as of recent estimates, reflecting reliance on these primary activities over diversified industry.[52][49]Development Challenges and Reforms

Mohéli faces significant infrastructure deficits that hinder economic integration and growth, particularly in inter-island connectivity, where inadequate maritime transport exacerbates isolation and limits access to markets and services. The World Bank's Comoros Interisland Connectivity Project, approved in 2022, addresses these gaps by improving port facilities and vessel operations, noting that existing infrastructure fails to support inclusive socioeconomic development across islands including Mohéli, where cyclone damage has further degraded transport links.[53][54] High underemployment persists amid a youthful population, with national labor force challenges indicating a deteriorating employment situation over the past two decades, driven by limited job creation in a subsistence-based economy.[55] Corruption undermines governance and investor confidence, with Comoros scoring 21 out of 100 on Transparency International's 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index, ranking 158th out of 180 countries, reflecting systemic issues in public sector accountability that extend to island-level administration.[56] Brain drain compounds skilled labor shortages, as evidenced by a high human flight index of 7.1 out of 10 in 2024, with remittances forming a key economic pillar but failing to offset the loss of human capital essential for private sector expansion.[57] A state-dominated economy, reliant on foreign aid for over a quarter of GDP in projects like post-2010 World Bank initiatives, stifles entrepreneurial activity through regulatory barriers and limited incentives for local enterprise, prioritizing public spending over market-driven growth.[32] Reforms in the 2020s have targeted fiscal management and investment attraction, including the IMF-supported Extended Credit Facility arrangement, which emphasizes building fiscal buffers and modernizing tax administration to reduce aid dependency, though implementation lags have yielded only modest results.[58] A revised Investment Code offers incentives for sectors like tourism, such as tax exemptions for qualifying projects, aiming to diversify beyond agriculture and fisheries, but bureaucratic hurdles persist in attracting private capital to Mohéli's eco-tourism potential.[59] These efforts have supported annual GDP growth of around 3.2% in recent years, yet poverty remains entrenched at approximately 38-45% of the population living below national lines, highlighting policy execution shortfalls over external factors like geographic isolation.[60][61][62]Demographics and Society

Population Distribution and Communities

Mohéli's population was estimated at 56,526 in 2020, with nearly half (49.1%) residing in rural areas.[2] The island spans 290 square kilometers, yielding a population density of approximately 195 inhabitants per square kilometer. Settlement patterns feature concentration along the coasts, particularly in the capital Fomboni, which houses around 15,000 residents, and smaller coastal villages such as Nioumachoua and Mutsamudu.[63] Inland areas remain sparsely populated due to rugged terrain and limited arable land. The island experiences population growth aligned with national trends, at about 1.34% annually as of recent estimates. This is driven by a total fertility rate of approximately 4.3 children per woman, higher in rural zones.[64] Net migration is negative, with significant outflows to Mayotte and metropolitan France, often undocumented and motivated by economic opportunities; thousands attempt perilous sea crossings from Comoros islands annually.[65] Residents are ethnically homogeneous, comprising Comorians of mixed African-Arab ancestry, similar to those on Grande Comore and Anjouan.[66] A small expatriate presence exists, primarily foreign conservation workers supporting marine and biodiversity initiatives.[2] Communities are predominantly village-based, with urban-rural divides reflecting limited internal mobility.Cultural Practices and Social Structure

The predominant religion in Mohéli is Sunni Islam of the Shafi'i school, which permeates daily life through regular mosque attendance, adherence to Islamic dress codes, and observance of festivals such as Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, where communal prayers and feasts reinforce social bonds.[67] These practices blend with local customs, including ritual recitations during celebrations known as ada, which feature storytelling from oral histories that preserve genealogies and moral lessons passed down through generations.[67] Social structure in Mohéli retains matrilineal elements inherited from Bantu-speaking African ancestors, with landholdings such as magnahouli controlled and inherited through the female line, conferring authority to female elders in family decisions and resource allocation.[68] Matrilocal residence patterns—where couples live near the wife's family—further underscore women's central role in kinship networks, contrasting with patrilineal norms prevalent among Arab-influenced coastal East African societies.[67] This system fosters communal solidarity, with elders mediating disputes and guiding youth through proverbs and traditions emphasizing respect for lineage and hospitality.[69] Cultural expressions include traditional music and dance performed at weddings and harvests, incorporating rhythmic ngoma drums, violin-like instruments, and fusion styles drawing from Arab trader influences since the 8th century, such as melodic taarab variants adapted locally.[70] Artisanal crafts like embroidery, weaving, and wood carving reflect these hybrid roots, often produced by women for ceremonial attire and household items, symbolizing continuity amid Islamic prohibitions on figurative art.[71] Oral traditions remain vital, with elders recounting epic tales of migration and sultanates that differentiate Mohéli's insular identity from mainland African patrilineal groups.[72]Environment and Biodiversity

Unique Flora and Fauna

Mohéli's forests harbor several endemic avian species, including the Moheli brush warbler (Nesillas mariae), a medium-sized, yellowish-brown passerine restricted to remnant montane forest fragments on the island, where it forages in understory vegetation.[73] The Moheli scops owl (Otus moheliensis), another island endemic, inhabits humid forests and contributes to insect control in these ecosystems.[74] Surveys indicate Mohéli supports at least 74 bird species overall, with endemics playing key roles in seed dispersal and pollination within the island's volcanic-derived soils.[75] The island's flora includes endemic orchids and ferns adapted to nutrient-rich volcanic substrates, which foster diverse understory communities in lowland and montane habitats.[76] These plants, alongside tree ferns and dwarf palms, form critical structural elements in forests, supporting herbivory and microhabitats for invertebrates.[77] Marine environments feature fringing coral reefs and mangroves that sustain high fish diversity, with surveys in Mohéli recording numerous reef-associated species integral to trophic chains.[78] Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas), with an estimated 5,000 nesting females, and hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) utilize seagrass beds and reefs for foraging on algae and sponges, maintaining ecosystem health through grazing and bioturbation.[79] These reptiles, concentrated at sites like Itsamia, enhance nutrient cycling between marine and coastal zones.[80]Conservation Efforts and Protected Areas

The Mohéli Marine Park, established in 2001 as the first protected marine area in the Comoros archipelago, encompasses approximately 437 km² of ocean surrounding the island, including key islets such as Nioumachoua.[81][82] This co-managed initiative involves local communities in enforcement through patrols that have curtailed illegal fishing activities, fostering sustainable resource use via no-take zones and regulated access.[83][84] In 2022, the Comoros government announced plans to expand its national protected areas network from one (Mohéli) to six, incorporating additional sites on Mohéli focused on terrestrial and coastal extensions to enhance connectivity with existing marine protections.[85] These efforts include community-led protections for sea turtle nesting sites, supported by funding from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Global Environment Facility (GEF), which have enabled habitat restoration and monitoring programs yielding higher nesting success rates.[86][87] Boundouni Lake, integrated into the park as the archipelago's first nature reserve, received UNDP backing for conservation infrastructure completed by 2024.[86] Measurable outcomes include elevated fish catches in adjacent fishing grounds, attributed to spillover effects from enforced no-take zones, with villagers reporting sustained increases in yields that supported investments in surveillance and tourism boats.[88] International collaborations, such as the designation of Mohéli as a Mission Blue Hope Spot in 2020, have bolstered data collection on marine species and promoted sustainable fishing practices, contributing to overall ecosystem resilience.[84]Threats to Environment and Development Trade-offs

Environmental Risks and Human Impacts

Mohéli experiences significant deforestation driven by agricultural expansion and fuelwood collection, contributing to a broader 28% loss of forest cover across the Comoros archipelago over the past two decades.[89] This habitat loss exacerbates soil erosion, with hillside farming and overgrazing accelerating runoff and sediment transport into coastal zones.[87] Coastal erosion has intensified as a result, with satellite data identifying 19 erosion hotspots on Mohéli, linked to both natural wave action and human-induced beach sand extraction for construction.[90] Introduced invasive species, particularly black rats (Rattus rattus), pose a direct threat to native bird populations by preying on eggs and nestlings of endemic species such as the Moheli scops-owl (Otus moheliensis).[91] These rats, along with feral cats, were inadvertently transported via human maritime activities and have proliferated in forested and coastal habitats, reducing breeding success for ground-nesting avifauna.[92] Overfishing by local artisanal fleets further strains marine ecosystems, depleting reef-associated fish stocks and disrupting food webs that support biodiversity.[93] Agricultural runoff introduces pollutants, including fertilizers and sediments, into Mohéli's waterways and nearshore environments, stemming from intensive vanilla and ylang-ylang cultivation on steep slopes.[2] This nutrient loading promotes algal blooms and degrades coral reefs, while siltation from eroded soils smothers benthic habitats.[94] Climate change amplifies these pressures through rising sea levels, which exacerbate coastal inundation, and more frequent cyclones, such as those in the Western Indian Ocean basin, that increase storm surge and freshwater flooding.[95] Poaching of green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) persists despite legal protections, with illegal harvesting for meat and shells reducing nesting populations on Mohéli's beaches, one of the Indian Ocean's key rookeries.[96] Cross-border trade networks, facilitated by proximity to Madagascar, sustain demand for turtle products, leading to unreported takes that hinder population recovery.[97]Policy Debates on Conservation vs. Exploitation

In Mohéli, policy debates center on the Mohéli Marine Park, established in 2001 as the Comoros' first protected area and upgraded to national park status in 2015, which imposes zoning and gear restrictions on traditional fishing grounds encompassing ten villages.[98] Local fishers argue these measures exacerbate poverty by curtailing access to subsistence resources without commensurate economic alternatives, as studies indicate no broad consensus on regulatory impacts yielding higher fisheries yields and persistent income losses from prohibited methods like beach seining.[99][100] Co-management frameworks, intended to involve communities in enforcement, have faltered due to weak government capacity and social tensions, resulting in poaching and underscoring failed community buy-in where conservation benefits fail to offset livelihood restrictions.[101] NGO-driven advocacy for strict bans prioritizes biodiversity preservation, citing Mohéli's endemic species and reefs vulnerable to overexploitation, yet empirical assessments reveal that without verifiable fisheries spillovers or tourism revenue gains—ecotourism projections remain unrealized for most locals—such policies hinder GDP contributions from small-scale fisheries, which sustain over 40% of coastal households amid 45% national poverty rates.[88][102] Pro-exploitation viewpoints from residents emphasize sustainable harvesting for jobs, arguing over-conservation displaces poverty-driven users without addressing root causes like limited market access, as evidenced by persistent illegal extraction despite patrols.[103] During the 1997 separatist movement, Mohéli's independence declaration highlighted demands for autonomous resource control to prioritize local exploitation over federal conservation mandates, reflecting grievances that centralized policies undervalue island-specific economic needs amid political instability.[36] Recent forestry debates echo this, with calls for controlled logging to generate revenue—given ylang-ylang and timber potentials—clashing against preservationists' warnings of irreversible habitat loss, as Comoros-wide forest cover declined at one of the archipelago's highest rates due to subsistence pressures, though Mohéli's fragmentation remains lower.[104] Empirical cases illustrate trade-offs: stringent park enforcement correlates with suppressed local incomes absent alternative livelihoods, while lax regulation risks biodiversity collapse, as seen in adjacent unregulated zones exhibiting depleted stocks, yet data affirm poverty as the primary driver of unsustainable use over policy leniency alone.[105]Infrastructure and Access

Transportation Networks

Mohéli's internal transportation relies primarily on a road network spanning approximately 98 kilometers, with 84 kilometers paved, facilitating access between the main town of Fomboni and other settlements like Hoani and Ouallahii, though maintenance issues and seasonal flooding can disrupt connectivity.[106] The remaining unpaved portions, often dirt tracks, limit vehicle access to remote rural areas, where four-wheel-drive vehicles are recommended due to uneven terrain and erosion risks.[106] Public transport consists of shared minibuses (taxis-brousse) operating irregularly along principal routes, with fares typically low but services infrequent outside peak hours.[107] Maritime transport dominates inter-island and coastal linkages, as Mohéli lacks regular passenger ferries; instead, small open fishing boats known as vedettes provide the primary means for travel to Grande Comore (Moroni) or Anjouan, departing from ports like Fomboni or Hoani on an ad hoc basis dependent on weather and demand.[108] These vessels, often carrying 20-50 passengers, operate irregularly—sometimes weekly for cargo-passenger combinations but frequently delayed by rough seas during the rainy season (November to April)—with journeys to Moroni taking 4-6 hours and costing around 10,000-15,000 Comorian francs per person.[109] Cargo boats from Anjouan to Mohéli run weekly without fixed schedules, requiring inquiries at departure ports, and prioritize freight over passengers, exacerbating delays for essential goods.[110] The port of Fomboni (also called Boingoma) serves as the island's sole facility for significant cargo handling, featuring two small docks accommodating up to three vessels simultaneously, but its shallow berths and limited infrastructure restrict access to ships under 80 meters, leading to high unloading costs via lighters and frequent delays that heighten import dependency for fuel, food, and construction materials.[111] Capacity constraints, compounded by cyclone damage in events like Cyclone Kenneth in 2019, have prompted World Bank-funded rehabilitation efforts since 2020 to deepen approaches and expand piers, though operations remain vulnerable to swells and under-equipped for efficient container traffic.[112] Coastal villages inaccessible by road depend on these vedettes or canoes for daily goods transport, underscoring the network's fragility and reliance on informal, weather-sensitive boating.[113]Airport and Connectivity

Mohéli Bandar Es Eslam Airport (IATA: NWA, ICAO: FMCI), situated near the island's capital Fomboni, serves as the primary aviation facility with a single asphalt runway measuring 1,300 meters (4,265 feet) in length.[114] [115] This configuration limits operations to small turboprop aircraft, supporting domestic inter-island flights operated by carriers such as RKomor, which provide daily connections to Grande Comore and Anjouan except on Fridays.[107] The airport's modest capacity handles primarily local passenger and cargo traffic essential for island connectivity and access to Mohéli's ecotourism sites, though specific annual passenger volumes remain low and unreported in official statistics.[116] Constraints from the short runway and inadequate terminal facilities prevent international services, reinforcing the island's peripheral status within Comorian aviation networks.[112] Ongoing infrastructure challenges, including the need for runway extensions and safety upgrades, are addressed in initiatives like the World Bank's Comoros Inter-island Connectivity Project, aimed at enhancing reliability amid frequent service disruptions.[112] Limited flight options exacerbate isolation, particularly for urgent medical needs, where evacuations to facilities in Mayotte or beyond rely on irregular schedules, contributing to high costs and delays in the broader Comorian health system.[117] [118]Symbols and Identity

Historical Flags and Emblems

, white, and red, overlaid with a green isosceles triangle based at the hoist bearing a white crescent and four five-pointed stars representing the archipelago's islands.[120] On August 11, 1997, amid the Comorian crisis, Mohéli declared de facto independence, adopting a distinct flag of a yellow field charged with a central red five-pointed star to signify autonomy and separation from the federal government. Alternative designs, such as yellow with a white crescent and narrow black stripe, were reported in use during this period.[121] After the 2001 Fomboni Agreements restored unity under the Union of the Comoros constitution, which devolved powers to the autonomous islands, Mohéli retained the yellow flag with red star as its official local emblem, distinguishing it from the national flag while affirming island identity. Emblems specific to Mohéli remain limited, with the island sharing the national coat of arms—a green shield featuring a white crescent moon within sun rays, four stars, and the Arabic motto "Allah, Nation, Union"—adopted in 1977, without unique marine elements documented for the island.[121][120]References

- https://en.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Moheli

- https://en.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Anjouan