Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

NASA facilities

View on Wikipedia

There are NASA facilities across the United States and around the world. NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC provides overall guidance and political leadership to the agency.[1] There are 10 NASA field centers, which provide leadership for and execution of NASA's work. All other facilities fall under the leadership of at least one of these field centers.[2] Some facilities serve more than one application for historic or administrative reasons. NASA has used or supported various observatories and telescopes, and an example of this is the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility. In 2013 a NASA Office of the Inspector General's (OIG) Report recommended a Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRAC) style organization to consolidate NASA's little used facilities.[3] The OIG determined at least 33 of NASA's 155 facilities were underutilized.

List of field centers

[edit]NASA has ten field centers.[4] Four of these were inherited from its predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA); two others were transferred to NASA from the United States Army; and NASA commissioned and built the other four itself shortly after its formation in 1958.

Inherited from NACA

[edit]Langley Research Center (LaRC), founded in 1917, is the oldest of NASA's field centers, located in Hampton, Virginia. LaRC focuses primarily on aeronautical research, though the Apollo lunar lander was flight-tested at the facility and a number of high-profile space missions have been planned and designed on-site. Established in 1917 by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the center currently devotes two-thirds of its programs to aeronautics, and the rest to space.[5] LaRC researchers use more than 40 wind tunnels to study improved aircraft and spacecraft safety, performance, and efficiency. Both Langley Field and the Langley Laboratory are named for aviation pioneer Samuel Pierpont Langley.[6] Starting in 1958, when NASA started Project Mercury, LaRC housed the Space Task Group, which was expanded into the Manned Spacecraft Center and moved to Houston in 1961–1962.[7] The selection of Houston as the location of the Manned Spacecraft Center resulted in some controversy at NASA Langley and in the surrounding area at the time, given they had previously expected either for Langley to be expanded or for a nearby location in the Hampton Roads region to be selected for the center.[8]

Ames Research Center (ARC) at Moffett Field was founded on December 20, 1939. The center was named after Joseph Sweetman Ames, a founding member of the NACA.[9] ARC is one of NASA's 10 major field centers and is located in California's Silicon Valley. Historically, Ames was founded to do wind-tunnel research on the aerodynamics of propeller-driven aircraft; however, it has expanded its role to doing research and technology in aeronautics, spaceflight, and information technology.[10] It provides leadership in astrobiology, small satellites, robotic lunar exploration, intelligent/adaptive systems and thermal protection.

Glenn Research Center (GRC), formerly the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory, located in Brook Park, Ohio, was established in 1942 as a laboratory for aircraft engine research.[11] In 1999, the center was officially renamed the NASA John H. Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field after John Glenn, an American fighter pilot, astronaut and politician.[12] Glenn supports all of the agency's missions and major programs. Glenn excels in researching and developing innovative technologies for both aeronautics and space flight. A multitude of NASA missions have included elements from Glenn, from the Mercury and Gemini projects to the Space Shuttle Program and the International Space Station. The center's core competencies include air-breathing and in-space propulsion and cryogenics, communications, power energy storage and conversion, microgravity sciences, and advanced materials.[13]

Armstrong Flight Research Center (AFRC), established by NACA before 1946 and located inside Edwards Air Force Base, is NASA's premier site for aeronautical research and operates some of the most advanced aircraft in the world. On January 16, 2014, the center previously known as Dryden was renamed in honor of Neil Armstrong, the first astronaut to walk on the Moon.[14][15]

Transferred from the Army

[edit]The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), located in the San Gabriel Valley area of Los Angeles County, CA, was, together with ABMA, one of the agencies behind Explorer 1, America's first robotic satellite, and also together with ABMA one of the first agencies to become a part of NASA. The facility is headquartered in the city of La Cañada Flintridge [16][17] with a Pasadena mailing address. JPL is managed by the nearby California Institute of Technology (Caltech). The Laboratory's primary function is building and operating robotic planetary spacecraft, though it also conducts Earth-orbit and astronomy missions.[18] It is also responsible for operating NASA's Deep Space Network (DSN) which includes stations in Barstow, California; Madrid, Spain; and Canberra, Australia.[19]

Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), located on the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, is one of NASA's largest centers. MSFC is where the Saturn V rocket and Skylab were developed.[20] Marshall is NASA's lead center for International Space Station (ISS) design and assembly; payloads and related crew training; and was the lead for Space Shuttle propulsion and its external tank.[21] From December 1959, it contained the Launch Operations Directorate, which moved to Florida to become the Launch Operations Center on July 1, 1962.[22] The MSFC was named in honor of General George C. Marshall.[23] The center also operates the Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF) in New Orleans, Louisiana to build and assemble hardware components for space systems.[24]

Built by NASA

[edit]Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), located in Greenbelt, Maryland, was commissioned by NASA on March 1, 1959.[25] It is the largest combined organization of scientists and engineers in the United States dedicated to increasing knowledge of the Earth, the Solar System, and the Universe via observations from space. GSFC is a major U.S. laboratory for developing and operating unmanned scientific spacecraft. GSFC conducts scientific investigation, development and operation of space systems, and development of related technologies. Goddard scientists can develop and support a mission, and Goddard engineers and technicians can design and build the spacecraft for that mission. Goddard scientist John C. Mather shared the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on COBE. GSFC also operates two spaceflight tracking and data acquisition networks (the Space Network and the Near Earth Network), develops and maintains advanced space and Earth science data information systems, and develops satellite systems for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).[26] External facilities of the GSFC include the Wallops Flight Facility at Wallops Island, Virginia, the Goddard Institute for Space Studies at Columbia University, and the Katherine Johnson Independent Verification and Validation Facility in West Virginia.[27][28]

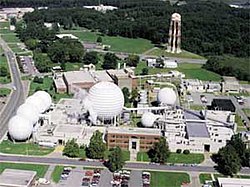

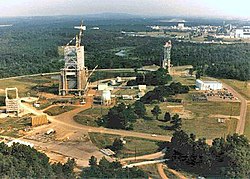

Stennis Space Center (SSC), originally the Mississippi Test Facility, is located in Hancock County, Mississippi, on the banks of the Pearl River at the Mississippi–Louisiana border. Commissioned on October 25, 1961, it was NASA's largest rocket engine test facility until the end of the Space Shuttle program. It is currently used for rocket testing by over 30 local, state, national, international, private, and public companies and agencies.[29][30] It also contains the NASA Shared Services Center.[31]

Johnson Space Center (JSC) is NASA’s center for human spaceflight training, research and flight control. Created as the Manned Spacecraft Center on November 1, 1961, the facility consists of a complex of 100 buildings constructed in 1962–1963 on 1,620 acres (660 ha) of land donated by Rice University in Houston, Texas.[32] The center grew out of the Space Task Group formed soon after the creation of NASA to co-ordinate the US human spaceflight program. It is home to the United States Astronaut Corps and is responsible for training astronauts from the U.S. and its international partners, and includes the Christopher C. Kraft Jr. Mission Control Center.[32] The center was renamed in honor of the late U.S. president and Texas native Lyndon B. Johnson on February 19, 1973.[33][34] JSC also operates the White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico to support rocket testing.

Kennedy Space Center (KSC), located west of Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, is one of the best known NASA facilities. Named the Launch Operations Center at its creation on July 1, 1962, it was renamed in honor of the late U.S. president on November 29, 1963,[35][36] and has been the launch site for every United States human space flight since 1968. KSC continues to manage and operate uncrewed rocket launch facilities for America's civilian space program from three pads at Cape Canaveral. Its Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) is the eighth-largest structure in the world by volume and was the largest when completed in 1965.[37] A total of 10,733 people worked at the center as of September 2021. Approximately 2,140 are employees of the federal government; the rest are contractors.[38]

Other facilities

[edit]

Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (CDSCC) is a ground station that is located in Australia at Tidbinbilla outside Canberra. The complex is part of the Deep Space Network run by JPL. It is commonly referred to as the Tidbinbilla Deep Space Tracking Station and was officially opened on 19 March 1965. The station is separated from Canberra by the Coolamon Ridge, Urambi Hills and Bullen Range that help shield the city's radio frequency (RF) noise from the dishes.

Madrid Deep Space Communications Complex (MDSCC), in Spanish and officially Complejo de Comunicaciones de Espacio Profundo de Madrid, is a satellite ground station located in Robledo de Chavela, Spain, and operated by the Instituto Nacional de Técnica Aeroespacial (INTA) that is a part of the Deep Space Network of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)

In addition to JPL (above), there are other Government-Owned / Contractor-Operated NASA facilities operated under grant provisions, such as the Space Telescope Science Institute at Johns Hopkins University which operates the Hubble Space Telescope.

Organization

[edit]List of minor facilities

[edit]

Communication and telescope facilities[edit]

|

Manufacturing, test and research facilities[edit]

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Shouse, Mary (July 9, 2009). "Welcome to NASA Headquarters". Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ "NASA Center Assignments by State". NASA. 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2013-01-23.

- ^ "Does NASA Need a Closure Commission To Shut Down Idle Facilities? – SpaceNews.com". 1 April 2013. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014.

- ^ "NASA Facilities and Centers" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (January 5, 2017). "What to Know About the Real Research Lab From Hidden Figures". Time. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Tennant, Diane (September 5, 2011). "What's in a name? NASA Langley Research Center". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ Swenson Jr., Lloyd S.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. "Space Task Group Gets a New Home and Name". This New Ocean, SP-4201. NASA. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ Korsgaard, Sean (20 July 2019). "Williamsburg recalls watching Apollo 11 and helping crew get there". Virginia Gazette, Daily Press. Tribune Media. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert (January 15, 2014). "Should NASA Ames Be Renamed After Sally Ride?". space.com. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Tillman, Nola (January 12, 2018). "Ames Research Center: R&D Lab for NASA". space.com. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "NASA Glenn's Historical Timeline". NASA. April 16, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "NASA Glenn Research Center Name Change". NASA. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "History of John H. Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field". NASA. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "House passes bill to rename NASA facility for Armstrong". Spaceflight Now. 2012-12-31. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ "NASA Center Redesignated for Neil Armstrong; Test Range for Hugh Dryden". 9 March 2015. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ "Why does everyone say NASA's JPL is in Pasadena when this other city is its real home?". 14 July 2016.

- ^ NASA.gov

- ^ Voosen, Paul (June 3, 2022). "New director of NASA's storied Jet Propulsion Lab takes on ballooning mission costs". science.com. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ Werner, Debra (January 27, 2022). "Microsoft helps JPL with Deep Space Network scheduling". Space News. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (August 6, 2018). "Rocket City, Alabama: Space history and an eye on the future". ap news. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Fentress, Steve (July 6, 2021). "NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center: A hub for historic and modern-day rocket power". space.com. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ "MSFC_Fact_sheet" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ "Marshall Space Flight Center, ca. 1960s". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 2021-09-14.

- ^ Haines, Matt (November 14, 2019). "New Orleans' NASA Michoud Facility Is The History And Future Of Space Exploration". verylocal.com. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "History of Goddard Space Flight Center". NASA. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ Fentress, Steve (February 10, 2020). "NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center: Exploring Earth and space by remote control". space.com. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ "About NASA's IV&V Program". NASA. March 9, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ Yan, Holly (February 24, 2019). "NASA renames facility for real-life 'Hidden Figures' hero Katherine Johnson". CNN. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ Lopez, Kenny (August 9, 2022). "Stennis Space Center tests rocket engines that will be used in NASA's historic Artemis I mission to the moon". WGNO TV. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "Stennis Space Center set for active testing year". Meridian Star. January 22, 2022. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ Dubuisson, Rebecca (July 19, 2007). "NASA Shared Services Center Background". Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ a b NASA. "Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center". Archived from the original on 1998-12-01. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "Houston Space Center Is Named for Johnson". The New York Times. February 20, 1973. p. 19.

- ^ Nixon, Richard M. (February 19, 1973). "50 - Statement About Signing a Bill Designating the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, as the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center". Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ "The National Archives, Lyndon B. Johnson Executive Order 11129". Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "Kennedy Space Center Story". NASA. 1991. Archived from the original on May 20, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Senate". Congressional Record: 17598. September 8, 2004.

- ^ "Kennedy Space Center Annual Report (2021)" (PDF). nasa.gov. November 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2022.