Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nicotine dependence

View on Wikipedia| Nicotine dependence | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Nicotine addiction; tobacco dependence; tobacco use disorder; cigarette dependence |

| Video of medical explanation of nicotine dependence and its health effects | |

| Complications | Health effects of tobacco |

| Prognosis | 10-year shorter lifespan[notes 1] |

| Prevalence | 1.2 billion tobacco users globally (2022)[2] |

| Deaths | 8 million per year (2023)[3] |

Nicotine dependence[notes 2] is a state of substance dependence on nicotine.[4] It is a chronic, relapsing disease characterized by a compulsive craving to use the drug despite social consequences, loss of control over drug intake, and the emergence of withdrawal symptoms.[8] Tolerance is another component of drug dependence.[9] Nicotine dependence develops over time as an individual continues to use nicotine.[9] While cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product, all forms of tobacco use—including smokeless tobacco and e-cigarette use—can cause dependence.[3][10] Nicotine dependence is a serious public health problem because it leads to continued tobacco use and the associated negative health effects. Tobacco use is one of the leading preventable causes of death worldwide, causing more than 8 million deaths per year and killing half of its users who do not quit.[3][11] Current smokers are estimated to die an average of 10 years earlier than non-smokers.[1]

According to the World Health Organization, "Greater nicotine dependence has been shown to be associated with lower motivation to quit, difficulty in trying to quit, and failure to quit, as well as with smoking the first cigarette earlier in the day and smoking more cigarettes per day."[12] The WHO estimates that there were 1.24 billion tobacco users globally in 2022[update], with the number projected to decline to 1.20 billion in 2025.[2] Of the 34 million smokers in the United States in 2018, 74.6% smoked every day, indicating the potential for some level of nicotine dependence.[13] There is an increased incidence of nicotine dependence in individuals with psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety disorders and substance use disorders.[14][15]

Various methods exist for measuring nicotine dependence.[6] Common assessment scales for cigarette smokers include the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria, the Cigarette Dependence Scale, the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale, and the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives.[6]

Nicotine is a parasympathomimetic stimulant[16] that binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain.[17] Neuroplasticity within the brain's reward system, including an increase in the number of nicotine receptors, occurs as a result of long-term nicotine use and leads to nicotine dependence.[4] In contrast, the effect of nicotine on human brain structure (e.g., gray matter and white matter) is less clear.[18] Genetic risk factors contribute to the development of dependence.[19] For instance, genetic markers for specific types of nicotinic receptors (the α5–α3–β4 nicotinic receptors) have been linked to an increased risk of dependence.[19] Evidence-based treatments—including medications such as nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, varenicline, or cytisine, and behavioral counseling—can double or triple a smoker's chances of successfully quitting.[20]

Definition

[edit]Nicotine dependence is defined as a neurobiological adaptation to repeated drug exposure that is manifested by highly controlled or compulsive use, the development of tolerance, experiencing withdrawal symptoms upon cessation including cravings, and an inability to quit despite harmful effects.[9] Nicotine dependence has also been conceptualized as a chronic, relapsing disease.[20] A 1988 Surgeon General report states, "Tolerance" is another aspect of drug addiction [dependence] whereby a given dose of a drug produces less effect or increasing doses are required to achieve a specified intensity of response. Physical dependence on the drug can also occur, and is characterized by a withdrawal syndrome that usually accompanies drug abstinence. After cessation of drug use, there is a strong tendency to relapse."[9]

Nicotine dependence leads to heavy smoking and causes severe withdrawal symptoms and relapse back to smoking.[9] Nicotine dependence develops over time as a person continues to use nicotine.[9] Teenagers do not have to be daily or long-term smokers to show withdrawal symptoms.[22] Relapse should not frustrate the nicotine user from trying to quit again.[20] A 2015 review found "Avoiding withdrawal symptoms is one of the causes of continued smoking or relapses during attempts at cessation, and the severity and duration of nicotine withdrawal symptoms predict relapse."[23] Symptoms of nicotine dependence include irritability, anger, impatience, and problems in concentrating.[24]

Diagnosis

[edit]There are different ways of measuring nicotine dependence.[6] The five common dependence assessment scales are the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the Cigarette Dependence Scale, the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale, and the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives.[6]

The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence focuses on measuring physical dependence which is defined "as a state produced by chronic drug administration, which is revealed by the occurrence of signs of physiological dysfunction when the drug is withdrawn; further, this dysfunction can be reversed by the administration of drug".[6] The long use of Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence is supported by the existence of significant preexisting research, and its conciseness.[6]

The 4th edition of the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-IV) had a nicotine dependence diagnosis which was defined as "...a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological symptoms..."[6] In the updated DSM-5 there is no nicotine dependence diagnosis, but rather Tobacco Use Disorder, which is defined as, "A problematic pattern of tobacco use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least 2 of the following [11 symptoms], occurring within a 12-month period."[25]

The Cigarette Dependence Scale was developed "to index dependence outcomes and not dependence mechanisms".[6] The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale, "a 19-item self-report measure, was developed as a multidimensional scale to assess nicotine dependence".[6] The Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives "is a 68-item measure developed to assess dependence as a motivational state".[6]

Mechanisms

[edit]Traditional cigarettes are the most common delivery device for nicotine.[26] However, electronic cigarettes are becoming more popular.[27] Nicotine can also be delivered via other tobacco products such as chewing tobacco, snus, pipe tobacco, hookah, all of which can produce nicotine dependence.[28]

Biomolecular

[edit]

Pre-existing cognitive and mood disorders may influence the development and maintenance of nicotine dependence.[29] Nicotine is a parasympathomimetic stimulant[16] that binds to and activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain,[17] which subsequently causes the release of dopamine and other neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine, acetylcholine, serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, endorphins,[30] and several neuropeptides.[31] Repeated exposure to nicotine can cause an increase in the number of nicotinic receptors, which is believed to be a result of receptor desensitization and subsequent receptor upregulation.[30] This upregulation or increase in the number of nicotinic receptors significantly alters the functioning of the brain reward system.[32] With constant use of nicotine, tolerance occurs at least partially as a result of the development of new nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain.[30] After several months of nicotine abstinence, the number of receptors go back to normal.[17] Nicotine also stimulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the adrenal medulla, resulting in increased levels of adrenaline and beta-endorphin.[30] Its physiological effects stem from the stimulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which are located throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems.[33] Chronic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation from repeated nicotine exposure can induce strong effects on the brain, including changes in the brain's physiology, that result from the stimulation of regions of the brain associated with reward, pleasure, and anxiety.[34] These complex effects of nicotine on the brain are still not well understood.[34]

When these receptors are not occupied by nicotine, they are believed to produce withdrawal symptoms.[35] These symptoms can include cravings for nicotine, anger, irritability, anxiety, depression, impatience, trouble sleeping, restlessness, hunger, weight gain, and difficulty concentrating.[36]

Neuroplasticity within the brain's reward system occurs as a result of long-term nicotine use, leading to nicotine dependence.[4] There are genetic risk factors for developing dependence.[19] For instance, genetic markers for a specific type of nicotinic receptor (the α5-α3-β4 nicotine receptors) have been linked to increased risk for dependence.[19][37] The most well-known hereditary influence related to nicotine dependence is a mutation at rs16969968 in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor CHRNA5, resulting in an amino acid alteration from aspartic acid to asparagine.[38] The single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs6474413 and rs10958726 in CHRNB3 are highly correlated with nicotine dependence.[39] Many other known variants within the CHRNB3–CHRNA6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are also correlated with nicotine dependence in certain ethnic groups.[39] There is a relationship between CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and complete smoking cessation.[40] Increasing evidence indicates that the genetic variant CHRNA5 predicts the response to smoking cessation medicine.[40]

Psychosocial

[edit]In addition to the specific neurological changes in nicotinic receptors, there are other changes that occur as dependence develops.[citation needed] Through various conditioning mechanisms (operant and cue/classical), smoking comes to be associated with different mood and cognitive states as well as external contexts and cues.[32]

Treatment

[edit]There are treatments for nicotine dependence, although the majority of the evidence focuses on treatments for cigarette smokers rather than people who use other forms of tobacco (e.g., chew, snus, pipes, hookah, e-cigarettes).[citation needed] Evidence-based medicine can double or triple a smoker's chances of quitting successfully.[20] Mental health conditions, especially Major depressive disorder, may also impact the success of attempts to quit smoking.[41]

Medication

[edit]There are eight major evidence-based medications for treating nicotine dependence: bupropion, cytisine (not approved for use in some countries, including the US), nicotine gum, nicotine inhaler, nicotine lozenge/mini-lozenge, nicotine nasal spray, nicotine patch, and varenicline.[42] These medications have been shown to significantly improve long-term (i.e., 6-months post-quit day) abstinence rates, especially when used in combination with psychosocial treatment.[20] The nicotine replacement treatments (i.e., patch, lozenge, gum) are dosed based on how dependent a smoker is—people who smoke more cigarettes or who smoke earlier in the morning use higher doses of nicotine replacement treatments.[citation needed] There is no consensus for remedies for tobacco use disorder among pregnant smokers who also use alcohol and stimulants.[7]

Vaccine

[edit]TA-NIC is a proprietary vaccine in development similar to TA-CD but being used to create human anti-nicotine antibodies in a person to destroy nicotine in the human body so that it is no longer effective.[43]

Psychosocial

[edit]Psychosocial interventions delivered in-person (individually or in a group) or over the phone (including mobile phone interventions) have been shown to effectively treat nicotine dependence.[42] These interventions focus on providing support for quitting and helping with smokers with problem-solving and developing healthy responses for coping with cravings, negative moods, and other situations that typically lead to relapse.[citation needed] The combination of pharmacotherapy and psychosocial interventions has been shown to be especially effective.[20]

Emerging Medical Treatment

[edit]A non-invasive, brain-based therapy called rTMS (repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation) gained FDA approval in 2020 for treating nicotine addiction and aiding the quitting process.[44] Studies have found patients who undergo rTMS have reduced cigarette cravings and number of cigarettes smoked, as well as greater long term success with cessation.[45] While this therapy is relevantly new for treating nicotine additions, it has a longer history as a therapeutic treatment for Major depressive disorder, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, and migraines. Side effects of this therapy are relatively mild because of the noninvasive nature of the treatment.

Epidemiology

[edit]First-time nicotine users develop a dependence about 32% of the time.[46] There are approximately 976 million smokers in the world.[47] Estimates are that half of smokers (and one-third of former smokers) are dependent based on DSM criteria, regardless of age, gender or country of origin, but this could be higher if different definitions of dependence were used.[48] Recent data suggest that, in the United States, the rates of daily smoking and the number of cigarettes smoked per day are declining, suggesting a reduction in population-wide dependence among current smokers.[49] However, there are different groups of people who are more likely to smoke than the average population, such as those with low education or low socio-economic status and those with mental illness.[49] There is also evidence that among smokers, some subgroups may be more dependent than other groups.[citation needed] Men smoke at higher rates than do women and score higher on dependence indices; however, women may be less likely to be successful in quitting, suggesting that women may be more dependent by that criterion.[49][50] There is an increased frequency of nicotine dependence in people with anxiety disorders.[14] 6% of smokers who want to quit smoking each year are successful at quitting.[51] Nicotine withdrawal is the main factor hindering smoking cessation.[52] A 2010 World Health Organization report states, "Greater nicotine dependence has been shown to be associated with lower motivation to quit, difficulty in trying to quit, and failure to quit, as well as with smoking the first cigarette earlier in the day and smoking more cigarettes per day."[53] E-cigarettes may result in starting nicotine dependence again.[54] Greater nicotine dependence may result from dual use of traditional cigarettes and e-cigarettes.[54] Like tobacco companies did in the last century, there is a possibility that e-cigarettes could result in a new form of dependency on nicotine across the world.[55]

Concerns

[edit]Nicotine dependence results in substantial mortality, morbidity, and socio-economic impacts.[51] Nicotine dependence is a serious public health concern due to it being one of the leading causes of avoidable deaths worldwide.[51] The medical community is concerned that e-cigarettes may escalate global nicotine dependence, particularly among adolescents who are attracted to many of the flavored e-cigarettes.[56] There is strong evidence that vaping induces symptoms of dependence in users.[57] Many organizations such the World Health Organization, American Lung Association, and Australian Medical Association do not approve of vaping for quitting smoking in youth, making reference to concerns about their safety and the potential that experimenting with vaping may result in nicotine dependence and later tobacco use.[58]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Stratton, Kathleen; Kwan, Leslie Y.; Eaton, David L. (January 2018). Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes (PDF). National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. pp. 1–774. doi:10.17226/24952. ISBN 978-0-309-46834-3. PMID 29894118.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Banks, Emily; Joshy, Grace; Weber, Marianne F; Liu, Bette; Grenfell, Robert; Egger, Sam; Paige, Ellie; Lopez, Alan D; Sitas, Freddy; Beral, Valerie (2015-02-24). "Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study: findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence". BMC Medicine. 13 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0281-z. ISSN 1741-7015. PMC 4339244. PMID 25857449.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2024-01-16). WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco use 2000–2030 (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 19. ISBN 978-92-4-008828-3. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ a b c "Tobacco". www.who.int. 2024-07-31. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ a b c d D'Souza MS, Markou A (2011). "Neuronal mechanisms underlying development of nicotine dependence: implications for novel smoking-cessation treatments". Addict Sci Clin Pract. 6 (1): 4–16. PMC 3188825. PMID 22003417.

- ^ Stratton 2018, p. Dependence and Abuse Liability, 256.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Piper, Megan; McCarthy, Danielle; Baker, Timothy (2006). "Assessing tobacco dependence: A guide to measure evaluation and selection". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 8 (3): 339–351. doi:10.1080/14622200600672765. ISSN 1462-2203. PMID 16801292. S2CID 22437505.

- ^ a b Akerman, Sarah C.; Brunette, Mary F.; Green, Alan I.; Goodman, Daisy J.; Blunt, Heather B.; Heil, Sarah H. (2015). "Treating Tobacco Use Disorder in Pregnant Women in Medication-Assisted Treatment for an Opioid Use Disorder: A Systematic Review". Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 52: 40–47. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2014.12.002. ISSN 0740-5472. PMC 4382443. PMID 25592332.

- ^ Falcone, Mary; Lee, Bridgin; Lerman, Caryn; Blendy, Julie A. (2015). "Translational Research on Nicotine Dependence". Translational Neuropsychopharmacology. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Vol. 28. pp. 121–150. doi:10.1007/7854_2015_5005. ISBN 978-3-319-33911-5. ISSN 1866-3370. PMC 3579204. PMID 26873019.

- ^ a b c d e f U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1988). The health consequences of smoking: Nicotine addiction: A report of the Surgeon General (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Health Promotion and Education, Office on Smoking and Health. DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 88-8406. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2011.

- ^ Jankowski, Mateusz; Krzystanek, Marek; Zejda, Jan Eugeniusz; Majek, Paulina; Lubanski, Jakub; Lawson, Joshua Allan; Brozek, Grzegorz (2019-06-27). "E-Cigarettes are More Addictive than Traditional Cigarettes-A Study in Highly Educated Young People". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 16 (13): 2279. doi:10.3390/ijerph16132279. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 6651627. PMID 31252671.

- ^ Doll, Richard; Peto, Richard; Boreham, Jillian; Sutherland, Isabelle (2004-06-22). "Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors". BMJ. 328 (7455): 1519. doi:10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.ae. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 437139. PMID 15213107.

- ^ "WHO | Gender, women, and the tobacco epidemic". WHO. Archived from the original on June 4, 2014. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ Creamer, MeLisa R. (2019). "Tobacco Product Use and Cessation Indicators Among Adults — United States, 2018". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (45): 1013–1019. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 6855510. PMID 31725711.

- ^ a b Moylan, Steven; Jacka, Felice N; Pasco, Julie A; Berk, Michael (2012). "Cigarette smoking, nicotine dependence and anxiety disorders: a systematic review of population-based, epidemiological studies". BMC Medicine. 10 (1): 123. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-123. ISSN 1741-7015. PMC 3523047. PMID 23083451.

- ^ Airagnes, Guillaume; Sánchez-Rico, Marina; Deguilhem, Amélia; Blanco, Carlos; Olfson, Mark; Ouazana Vedrines, Charles; Lemogne, Cédric; Limosin, Frédéric; Hoertel, Nicolas (2024-09-11). "Nicotine dependence and incident psychiatric disorders: prospective evidence from US national study". Molecular Psychiatry. 30 (3): 1080–1088. doi:10.1038/s41380-024-02748-6. ISSN 1476-5578. PMID 39261672.

- ^ a b Richard Beebe; Jeff Myers (19 July 2012). Professional Paramedic, Volume I: Foundations of Paramedic Care. Cengage Learning. pp. 640–. ISBN 978-1-133-71465-1.

- ^ a b c Bullen, Christopher (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes for Smoking Cessation". Current Cardiology Reports. 16 (11): 538. doi:10.1007/s11886-014-0538-8. ISSN 1523-3782. PMID 25303892. S2CID 2550483.

- ^ Hampton WH, Hanik I, Olson IR (2019). "[Substance Abuse and White Matter: Findings, Limitations, and Future of Diffusion Tensor Imaging Research]". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 197 (4): 288–298. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.02.005. PMC 6440853. PMID 30875650.

Heavy nicotine use in the form of smoking tobacco has been linked to neuropathy (Brody, 2006), often manifesting as prefrontal gray matter atrophy (Gallinat et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2011). Conversely, consumption of nicotine via smoking has been associated with higher white matter volume (Gazdzinski et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2011). Studies examining nicotine use via DTI have found similarly conflicting results. In chronic nicotine users, heavy consumption has been associated with lower FA (Lin et al., 2013) and higher FA (Paul et al., 2008), as well has both lower RD (Wang et al., 2017) and higher RD (Lin et al., 2013). The results of studies examining non-chronic, regular nicotine use are similarly split. Regular nicotine use has been associated with lower FA (Huang et al., 2013; Liao et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011) and higher FA (Hudkins et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2017). These seemingly conflicting nicotine results may be partly accounted for by the developmental stage in which it is consumed, with higher FA more commonly observed in younger nicotine users (Hudkins et al., 2012; Jacobsen et al., 2007). Alternatively, it maybe that the association between nicotine use and higher FA in adolescents is temporary, eventually leading to microstructural declines with chronic use. Future longitudinal studies could formally address this theory.

- ^ a b c d Saccone, NL; Culverhouse, RC; Schwantes-An, TH; Cannon, DS; Chen, X; Cichon, S; Giegling, I; Han, S; Han, Y; Keskitalo-Vuokko, K; Kong, X; Landi, MT; Ma, JZ; Short, SE; Stephens, SH; Stevens, VL; Sun, L; Wang, Y; Wenzlaff, AS; Aggen, SH; Breslau, N; Broderick, P; Chatterjee, N; Chen, J; Heath, AC; Heliövaara, M; Hoft, NR; Hunter, DJ; Jensen, MK; Martin, NG; Montgomery, GW; Niu, T; Payne, TJ; Peltonen, L; Pergadia, ML; Rice, JP; Sherva, R; Spitz, MR; Sun, J; Wang, JC; Weiss, RB; Wheeler, W; Witt, SH; Yang, BZ; Caporaso, NE; Ehringer, MA; Eisen, T; Gapstur, SM; Gelernter, J; Houlston, R; Kaprio, J; Kendler, KS; Kraft, P; Leppert, MF; Li, MD; Madden, PA; Nöthen, MM; Pillai, S; Rietschel, M; Rujescu, D; Schwartz, A; Amos, CI; Bierut, LJ (5 August 2010). "Multiple independent loci at chromosome 15q25.1 affect smoking quantity: a meta-analysis and comparison with lung cancer and COPD". PLOS Genetics. 6 (8) e1001053. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001053. PMC 2916847. PMID 20700436.

- ^ a b c d e f Fiore, MC; Jaen, CR; Baker, TB; et al. (2008). Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update (PDF). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-27. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- ^ "Anyone Can Become Addicted to Drugs". National Institute on Drug Abuse. July 2015.

- ^ Camenga, Deepa R.; Klein, Jonathan D. (2016). "Tobacco Use Disorders". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 25 (3): 445–460. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2016.02.003. ISSN 1056-4993. PMC 4920978. PMID 27338966.

- ^ Pistillo, Francesco; Clementi, Francesco; Zoli, Michele; Gotti, Cecilia (2015). "Nicotinic, glutamatergic and dopaminergic synaptic transmission and plasticity in the mesocorticolimbic system: Focus on nicotine effects". Progress in Neurobiology. 124: 1–27. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2014.10.002. ISSN 0301-0082. PMID 25447802. S2CID 207407218.

- ^ Shaik, Sabiha Shaheen (2016). "Tobacco Use Cessation and Prevention – A Review". Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 10 (5): ZE13-7. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2016/19321.7803. ISSN 2249-782X. PMC 4948554. PMID 27437378.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (22 May 2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub. p. 571. ISBN 978-0-89042-557-2.

- ^ "Exploring The Prevalence Of Smoking In The UK | News | Vaping Guides | IndeJuice (UK)". indejuice.com. Retrieved 2021-05-08.

- ^ Payne, JD; Orellana-Barrios, M; Medrano-Juarez, R; Buscemi, D; Nugent, K (2016). "Electronic cigarettes in the media". Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 29 (3): 280–3. doi:10.1080/08998280.2016.11929436. PMC 4900769. PMID 27365871.

- ^ Publishing, Harvard Health. "Breaking free from nicotine dependence". Harvard Health. Retrieved 2021-05-08.

- ^ Besson, Morgane; Forget, Benoît (2016). "Cognitive Dysfunction, Affective States, and Vulnerability to Nicotine Addiction: A Multifactorial Perspective". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 7: 160. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00160. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 5030478. PMID 27708591.

This article incorporates text by Morgane Besson and Benoît Forget available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Morgane Besson and Benoît Forget available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b c d Drug Therapeutics, Bulletin (2014). "Republished: Nicotine and health". BMJ. 349 (nov26 9) 2014.7.0264rep. doi:10.1136/bmj.2014.7.0264rep. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 25428425. S2CID 45426626.

- ^ Atta-ur- Rahman; Allen B. Reitz (1 January 2005). Frontiers in Medicinal Chemistry. Bentham Science Publishers. pp. 279–. ISBN 978-1-60805-205-9.

- ^ a b Martin-Soelch, Chantal (2013). "Neuroadaptive Changes Associated with Smoking: Structural and Functional Neural Changes in Nicotine Dependence". Brain Sciences. 3 (1): 159–176. doi:10.3390/brainsci3010159. ISSN 2076-3425. PMC 4061825. PMID 24961312.

- ^ Lushniak, Boris D.; Samet, Jonathan M.; Pechacek, Terry F.; Norman, Leslie A.; Taylor, Peter A. (2014). "Nicotine". The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Surgeon General of the United States. pp. 107–138. PMID 24455788.

- ^ a b Rowell, Temperance R; Tarran, Robert (2015). "Will Chronic E-Cigarette Use Cause Lung Disease?". American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 309 (12): L1398 – L1409. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00272.2015. ISSN 1040-0605. PMC 4683316. PMID 26408554.

- ^ Benowitz, NL (17 June 2010). "Nicotine addiction". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (24): 2295–303. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0809890. PMC 2928221. PMID 20554984.

- ^ "Nicotine and Tobacco". Medline Plus. 7 June 2016.

- ^ Ware, JJ; van den Bree, MB; Munafò, MR (2011). "Association of the CHRNA5-A3-B4 gene cluster with heaviness of smoking: a meta-analysis". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 13 (12): 1167–75. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr118. PMC 3223575. PMID 22071378.

- ^ Yu, Cassie; McClellan, Jon (2016). "Genetics of Substance Use Disorders". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 25 (3): 377–385. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2016.02.002. ISSN 1056-4993. PMID 27338962.

- ^ a b Wen, L; Yang, Z; Cui, W; Li, M D (2016). "Crucial roles of the CHRNB3–CHRNA6 gene cluster on chromosome 8 in nicotine dependence: update and subjects for future research". Translational Psychiatry. 6 (6): e843. doi:10.1038/tp.2016.103. ISSN 2158-3188. PMC 4931601. PMID 27327258.

- ^ a b Chen, Li-Shiun; Horton, Amy; Bierut, Laura (2018). "Pathways to precision medicine in smoking cessation treatments". Neuroscience Letters. 669: 83–92. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2016.05.033. ISSN 0304-3940. PMC 5115988. PMID 27208830.

- ^ Kaprio, J., Kinnunen, T. H., Korhonen, T., Latvala, A., Ranjit, A., Depressive symptoms predict smoking cessation in a 20-year longitudinal study of adult twins, Addictive Behaviors, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106427

- ^ a b Hartmann-Boyce, J; Stead, LF; Cahill, K; Lancaster, T (October 2013). "Efficacy of interventions to combat tobacco addiction: Cochrane update of 2012 reviews". Addiction. 108 (10): 1711–21. doi:10.1111/add.12291. PMID 23834141.

- ^ "CelticPharma: TA-NIC Nicotine Dependence". Archived from the original on 2009-12-06. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ Jordan, T., Apostol, M. R., Nomi, J., & Petersen, N, Unraveling neural complexity: Exploring brain entropy to yield mechanistic insight in neuromodulation therapies for tobacco use disorder, Imaging Neuroscience, 2024, https://doi-org.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/10.1162/imag_a_00061

- ^ Barnea-Ygael, N., Bystritsky, T., Casuto, L., Deutsch, F., Duffy, W., Feifel, D., George, M. S., Iosifescu, D. V., Li, X., Lipkinsky Grosz, M., Martinez, D., Morales, O., Moshe, H., Nunes, E. V., Roth, Y., Stein, A., Toder, D., Tendler, A., Winston, J., Ward, H., Wirecki, T., Vapnik, A. Zangen, A., Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for smoking cessation: A pivotal multicenter double‐blind randomized controlled trial, World Psychiatry, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20905

- ^ MacDonald, K; Pappa, K (April 2016). "WHY NOT POT?: A Review of the Brain-based Risks of Cannabis". Innov Clin Neurosci. 13 (3–4): 13–22. PMC 4911936. PMID 27354924.

- ^ Ng, M; Freeman, MK; Fleming, TD; Robinson, M; Dwyer-Lindgren, L; Thomson, B; Wollum, A; Sanman, E; Wulf, S; Lopez, AD; Murray, CJ; Gakidou, E (8 January 2014). "Smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980-2012". JAMA. 311 (2): 183–92. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284692. PMID 24399557.

- ^ Hughes, JR; Helzer, JE; Lindberg, SA (8 November 2006). "Prevalence of DSM/ICD-defined nicotine dependence". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 85 (2): 91–102. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.004. PMID 16704909.

- ^ a b c "Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2005–2013". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (63). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 1108–1112. 2014.

- ^ Weinberger, AH; Pilver, CE; Mazure, CM; McKee, SA (September 2014). "Stability of smoking status in the US population: a longitudinal investigation". Addiction. 109 (9): 1541–53. doi:10.1111/add.12647. PMC 4127136. PMID 24916157.

- ^ a b c Rachid, Fady (2016). "Neurostimulation techniques in the treatment of nicotine dependence: A review". The American Journal on Addictions. 25 (6): 436–451. doi:10.1111/ajad.12405. ISSN 1055-0496. PMID 27442267.

- ^ Wadgave, U; Nagesh, L (2016). "Nicotine Replacement Therapy: An Overview". International Journal of Health Sciences. 10 (3): 425–435. doi:10.12816/0048737. PMC 5003586. PMID 27610066.

- ^ "Gender, women, and the tobacco epidemic" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2013.

- ^ a b DeVito, Elise E.; Krishnan-Sarin, Suchitra (2017). "E-cigarettes: Impact of E-Liquid Components and Device Characteristics on Nicotine Exposure". Current Neuropharmacology. 15 (4): 438–459. doi:10.2174/1570159X15666171016164430. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 6018193. PMID 29046158.

- ^ Schraufnagel, Dean E. (2015). "Electronic Cigarettes: Vulnerability of Youth". Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonology. 28 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1089/ped.2015.0490. ISSN 2151-321X. PMC 4359356. PMID 25830075.

- ^ Palazzolo, Dominic L. (November 2013). "Electronic cigarettes and vaping: a new challenge in clinical medicine and public health. A literature review". Frontiers in Public Health. 1 (56): 56. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2013.00056. PMC 3859972. PMID 24350225.

- ^ Stratton 2018, p. Chapter 8-52.

- ^ Yoong, Sze Lin; Stockings, Emily; Chai, Li Kheng; Tzelepis, Flora; Wiggers, John; Oldmeadow, Christopher; Paul, Christine; Peruga, Armando; Kingsland, Melanie; Attia, John; Wolfenden, Luke (2018). "Prevalence of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use among youth globally: a systematic review and meta-analysis of country level data". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 42 (3): 303–308. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12777. hdl:1959.3/457642. ISSN 1326-0200. PMID 29528527.

External links

[edit]- Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton et al., 1991)

- Heaviness of Smoking Index (Heatherton et al., 1989) Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V (DSM-V)

- Tobacco Dependence Screener (Kawakami et al., 1999) Archived 2016-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS; Shiffman, Waters & Hickcox, 2004)

- Cigarette Dependence Scale (Etter et al., 2003)

- Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (Piper et al., 2004)

Nicotine dependence

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Core Symptoms and Diagnostic Criteria

Tobacco's habit-forming nature was recognized as early as the 16th–17th centuries, with historical accounts describing difficulty quitting.[13] Nicotine dependence manifests as a chronic pattern of nicotine-seeking behavior driven by neuroadaptations in reward and stress pathways, leading to compulsive use despite adverse health, social, or economic consequences. Diagnosis relies on standardized criteria from major classification systems, emphasizing behavioral, cognitive, and physiological indicators of impaired control. These criteria distinguish dependence from mere habitual use by requiring evidence of harm or distress, typically assessed via clinical interviews or validated scales like the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, which quantifies severity through items such as time to first cigarette and difficulty abstaining.[2] In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), nicotine dependence is subsumed under Tobacco Use Disorder, defined as a problematic pattern of tobacco use—via smoking, chewing, or other means—resulting in clinically significant impairment or distress, with at least two of the following 11 criteria met within a 12-month period:- Tobacco used in larger amounts or over longer periods than intended.

- Persistent desire or repeated unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use.

- Excessive time spent obtaining, using, or recovering from tobacco.

- Cravings or strong urges to use tobacco.

- Failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home due to recurrent use.

- Continued use despite persistent social or interpersonal problems caused or worsened by tobacco.

- Reduction or abandonment of important social, occupational, or recreational activities because of use.

- Recurrent use in physically hazardous situations (e.g., driving while impaired).

- Continued use despite awareness of physical or psychological problems likely caused or exacerbated by tobacco.

- Tolerance, marked by needing increased amounts to achieve effects or diminished effects from the same amount.

- Withdrawal symptoms or use of tobacco to relieve or avoid them.

Distinction from Tobacco Use Disorder

Nicotine dependence primarily denotes the physiological and psychological addiction to nicotine, the alkaloid responsible for the reinforcing effects in tobacco and other delivery systems, characterized by neuroadaptation, tolerance, and withdrawal upon cessation.[1] This concept emphasizes the drug's direct pharmacological actions on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, leading to dopamine release and compulsive seeking behavior, as evidenced by dependence scales like the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), which quantify symptoms such as smoking shortly after waking or difficulty refraining in no-smoking areas.[18] In contrast, Tobacco Use Disorder (TUD), as defined in the DSM-5 (2013), is a clinical diagnosis for a problematic pattern of tobacco use—encompassing combustible and smokeless products—resulting in clinically significant impairment or distress, requiring at least two of eleven criteria (e.g., using larger amounts over time, persistent desire to cut down, or continued use despite social or health problems) within a 12-month period.[19][1] The distinction arises because TUD integrates behavioral, cognitive, and contextual elements tied to tobacco consumption, including conditioned cues from smoking rituals and the health sequelae of tobacco-specific toxins beyond nicotine, such as tar and carcinogens, whereas nicotine dependence can manifest independently via non-tobacco vehicles like electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) or pharmaceutical nicotine replacement therapies (NRT).[20] For instance, while 60-80% of daily smokers meet TUD criteria, reflecting intertwined nicotine addiction and habitual tobacco use, heavy ENDS users may exhibit nicotine dependence symptoms without fulfilling TUD, as the diagnosis specifies tobacco products.[21][22] This separation highlights that nicotine's addictiveness drives initiation and maintenance, but TUD captures the broader morbidity of tobacco delivery, with epidemiological data showing TUD prevalence at approximately 13% among U.S. adults in 2020, predominantly among cigarette users.[23] Critically, the DSM-5's shift from "nicotine dependence" in DSM-IV to TUD reflects a focus on substance-specific use patterns rather than isolated drug effects, yet this can underemphasize nicotine's causal role in non-traditional products; studies indicate comparable dependence severity across delivery methods when nicotine intake is equated, underscoring that tobacco's harms amplify but do not solely define the disorder.[2][22] Source credibility in this domain favors peer-reviewed psychiatric and pharmacological literature over self-reported surveys, given potential underreporting biases in addiction research.[1]Biological Mechanisms

Neurochemical and Pharmacological Processes

Nicotine exerts its primary effects by binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which are ligand-gated ion channels predominantly composed of α and β subunits, located presynaptically and postsynaptically in the central nervous system.[3] Activation of these receptors by nicotine leads to an influx of cations, including sodium and calcium, depolarizing the neuron and facilitating the release of various neurotransmitters.[24] In the ventral tegmental area (VTA), nicotine stimulates nAChRs on dopaminergic neurons, enhancing firing rates and promoting dopamine release into the nucleus accumbens, a key component of the mesolimbic reward pathway.[25] This dopamine surge underlies the reinforcing properties of nicotine, as dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens modulates motivation, pleasure, and associative learning, thereby contributing to the initiation and maintenance of dependence.[25] Nicotine also indirectly boosts dopamine transmission by activating nAChRs on glutamatergic terminals projecting to the VTA, increasing excitatory input to dopamine neurons, while simultaneously modulating inhibitory GABAergic inputs.[26] Chronic exposure induces adaptive changes, including desensitization of high-affinity α4β2 nAChRs and upregulation of receptor density, particularly in response to low, sustained nicotine levels mimicking those from smoking.[27] Pharmacologically, nicotine functions as a partial agonist at nAChRs, producing biphasic effects: acute activation followed by desensitization, which alters the dynamic range of dopamine release and fosters tolerance.[28] Dependence emerges from this interplay, where repeated dosing counters desensitization-induced hypoactivity, while withdrawal precipitates deficits in dopamine and other neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine, driving negative reinforcement to alleviate dysphoria.[29] Subtype-specific contributions, such as α6β2 nAChRs dominating nicotine-evoked dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens, highlight targeted vulnerabilities in the reward circuitry.[30] Overall, these processes integrate positive hedonic reinforcement with negative affective states, cementing nicotine's addictive potential through neuroplastic adaptations in limbic and prefrontal regions.[3]Genetic Predispositions and Individual Variability

Twin and family studies have established that genetic factors account for 40% to 70% of the variance in nicotine dependence risk.[31] Heritability estimates for smoking initiation, a precursor to dependence, range from 46% to 84% in male twins, with similar patterns observed for persistent heavy smoking.[32] These figures derive from comparisons of monozygotic and dizygotic twins, isolating genetic from shared environmental influences, though adoption studies yield somewhat lower estimates, suggesting a role for non-shared environments in modulating expression.[33] Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have pinpointed key loci contributing to dependence susceptibility, with the CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 gene cluster on chromosome 15q25 emerging as the strongest signal.[34] This cluster encodes subunits of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, where variants like rs16969968 in CHRNA5 alter receptor sensitivity to nicotine, increasing reward salience and dependence liability, particularly among early-onset users.[35] Additional GWAS in diverse ancestries have identified novel regulatory SNPs near CHRNA5, explaining differences in dependence severity across populations, though these account for only a fraction of total heritability due to polygenic architecture.[36] SNP-based heritability for nicotine dependence measures, such as the Fagerström Test, is estimated at 8.6%, highlighting the distributed nature of genetic risk.[34] Variability in nicotine metabolism, driven by polymorphisms in the CYP2A6 gene, further differentiates dependence risk. CYP2A6 encodes the primary enzyme converting nicotine to cotinine; slow metabolizers (e.g., carriers of *2 or *4 alleles) exhibit 20-50% reduced clearance rates, leading to sustained nicotine levels that paradoxically deter heavy smoking and lower addiction odds by 50-70% compared to normal metabolizers.[37] [38] In adolescents, slow CYP2A6 activity correlates with accelerated dependence acquisition at low doses but caps overall consumption, illustrating how metabolic efficiency shapes intake patterns and tolerance development.[39] These variants explain up to 65% of inter-individual differences in nicotine pharmacokinetics, interacting with receptor genetics to amplify or mitigate vulnerability.[40] Collectively, these genetic elements underpin heterogeneous responses to nicotine, from heightened reinforcement in receptor variant carriers to protective effects in slow metabolizers, though full risk profiles involve hundreds of loci and gene-environment interplay.[41] Recent analyses confirm that while environmental triggers initiate use, inherited factors predominantly govern progression to chronic dependence.[34]Psychological and Behavioral Dimensions

Reinforcement Pathways and Habit Formation

Nicotine primarily reinforces behavior through activation of the mesolimbic dopamine system, where it binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) on dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), triggering phasic dopamine release into the nucleus accumbens (NAc).[42] This dopamine surge signals reward prediction errors, strengthening associations between nicotine intake and pleasurable outcomes, thus promoting initial drug-seeking via positive reinforcement.[43] Studies in rodents demonstrate that nicotine's direct and indirect stimulation of VTA dopamine neurons mimics natural rewards, facilitating operant conditioning for nicotine delivery.[42] Habit formation escalates as repeated nicotine exposure shifts control from ventral striatal goal-directed actions to habitual responding in the dorsal striatum.[44] Nicotine reduces inhibitory output from the dorsal striatum by enhancing GABAergic interneuron activity via α4β2 nAChRs, which diminishes behavioral flexibility and entrenches cue-driven smoking urges. Environmental cues paired with nicotine become potent via amplified dopamine signaling in cue-responsive circuits, leading to Pavlovian-instrumental transfer where cues alone elicit compulsive seeking.[45] Chronic administration sensitizes midbrain dopamine neurons, increasing activity bursts that sustain motivation despite diminishing hedonic effects, a process observed in rat models after weeks of exposure.[46] Negative reinforcement complements positive pathways by alleviating withdrawal-induced dysphoria, where nicotine restores baseline dopamine tone in depleted states, reinforcing use to avoid aversion.[17] This dual mechanism underlies dependence, with human imaging showing cue-reactivity persisting post-abstinence, driven by nicotine's enhancement of dopaminergic learning signals.[47] Overall, these pathways integrate pharmacological effects with associative learning, transitioning voluntary use to automatic habits resistant to extinction.[44]Withdrawal Symptoms and Tolerance Development

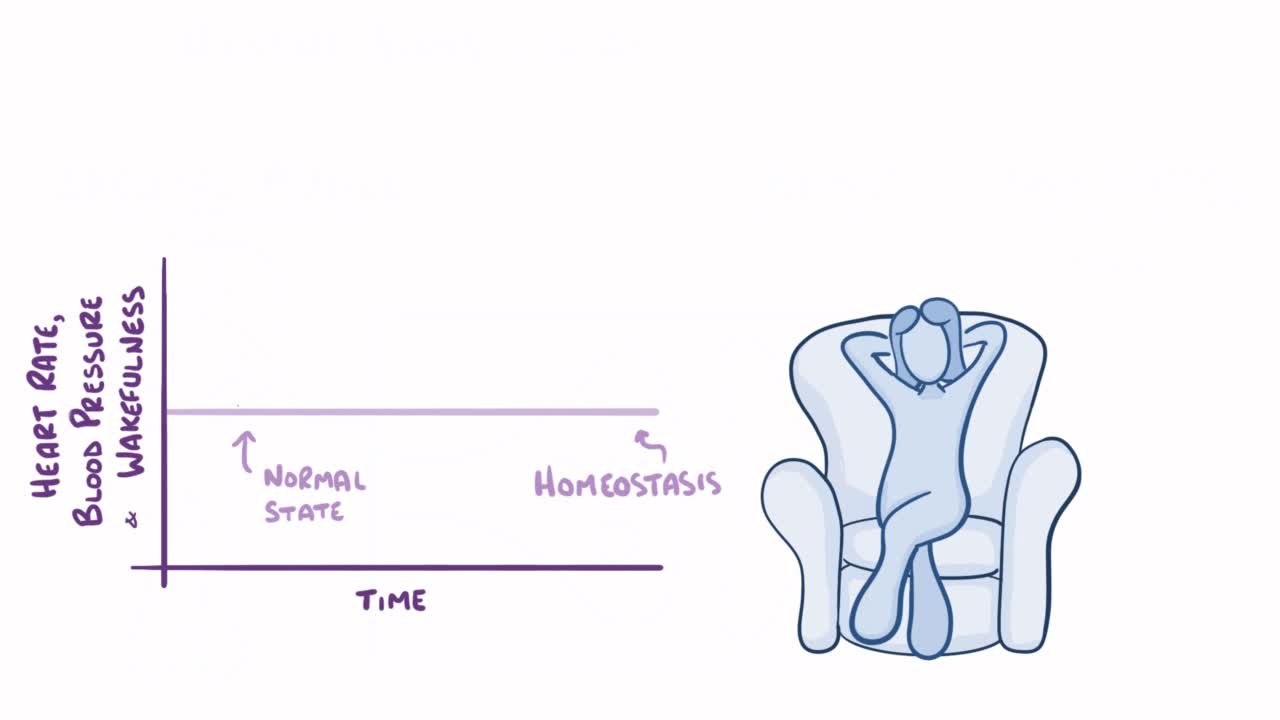

Nicotine withdrawal manifests as a cluster of affective, cognitive, and somatic symptoms following cessation or significant reduction in nicotine intake among dependent individuals. Common affective symptoms include irritability, anxiety, depression, dysphoria, and anhedonia, while somatic effects encompass tremors, bradycardia, hyperalgesia, and increased appetite.[7] [48] Cognitive impairments such as difficulty concentrating and restlessness are also prevalent, alongside intense cravings for nicotine that drive relapse.[8] [49] These symptoms typically emerge within hours of the last nicotine exposure, peak in intensity within 24 to 48 hours, and largely subside within one week, though cravings and some mood disturbances may persist for weeks or months.[48] The severity correlates with the degree of dependence, with heavier users experiencing more pronounced effects due to accumulated adaptations in brain reward pathways.[17] Tolerance to nicotine develops through repeated exposure, whereby the body adapts by reducing sensitivity to the drug's effects, necessitating higher doses to achieve the same pharmacological response. This process involves desensitization and upregulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the brain, particularly in mesolimbic dopamine pathways, leading to diminished subjective rewarding effects over time.[17] [50] Chronic administration induces behavioral tolerance, evident in attenuated responses to nicotine's stimulant properties, which reinforces continued use to counteract withdrawal and maintain homeostasis.[51] The interplay between tolerance and withdrawal underscores nicotine's dependence potential, as adaptive changes during chronic use precipitate dysphoric states upon abstinence, perpetuating the cycle of consumption. Evidence from human and animal models confirms that tolerance emerges rapidly with daily dosing and contributes to escalating intake patterns in dependent users.[27] [50]Epidemiology and Prevalence

Global and Regional Trends

Globally, tobacco use—a primary driver of nicotine dependence—has declined from 1.38 billion users in 2000 to 1.20 billion in 2024, representing a drop from approximately one in three adults to one in five.[52] This progress, equivalent to a 27% relative reduction since 2010, stems largely from tobacco control measures like taxation, advertising bans, and smoke-free policies, though the absolute number of users remains substantial, with over 80% concentrated in low- and middle-income countries.[52] [53] Among current tobacco users, nicotine dependence rates are high, with estimates indicating that roughly 70-80% of daily smokers meet clinical criteria for dependence, though direct global surveys on dependence (e.g., via DSM-5 or Fagerström Test) are less frequent than use prevalence data.[6] Regional disparities persist, with the WHO European Region exhibiting the highest adult tobacco use prevalence at 24.1% in 2024, down from 34.9% in 2000, driven by slower declines among women and rising e-cigarette use among youth.[54] In South-East Asia, male prevalence has halved from 70% in 2000 to 37% in 2024, reflecting aggressive interventions in countries like India, yet the region retains one of the largest absolute user bases due to population size.[52] The Americas show varied trends, with the U.S. adult cigarette smoking rate falling to 11.6% by 2022 amid declining youth initiation, but offset regionally by persistent use in Latin American countries where socioeconomic factors sustain dependence.[55] [56] Emerging patterns include a shift toward novel nicotine products, with approximately 100 million people using e-cigarettes, heated tobacco, or nicotine pouches by 2024, potentially introducing new dependence vectors among non-traditional users, particularly youth in high-income regions.[52] Despite overall declines, projections to 2030 indicate that without accelerated interventions, global tobacco use may stabilize above 1 billion users, perpetuating nicotine dependence burdens in aging populations and low-resource settings.[57]Demographic Risk Factors and Onset Patterns

Nicotine dependence typically emerges following early initiation of regular tobacco or nicotine product use, with the majority of affected individuals beginning daily smoking before age 25, and the rate accelerating between ages 15 and 20.[58] Nearly 90% of adults who smoke cigarettes daily first experimented with smoking by age 18, underscoring adolescence as a critical window for onset.[59] Initiation of regular smoking before age 21 is linked to elevated odds of subsequent nicotine dependence, with peak dependence risk associated with onset of regular use around age 10 and persisting heightened risk through age 20.[60][61] Among demographic groups, males exhibit higher prevalence of nicotine dependence than females, with U.S. data from 2015 showing 16.7% of adult males versus 13.6% of adult females reporting current tobacco use, a pattern consistent across most tobacco products.[62] This disparity holds in prevalence estimates, such as a 48% smoking rate among males compared to 27.6% among females in a hospital worker cohort.[63] Females may face amplified dependence risk due to faster nicotine metabolism and higher comorbidity with depression, though overall initiation and persistence rates remain lower than in males.[64] Age at assessment influences dependence severity, displaying an inverse U-shaped curve with peak nicotine dependence in middle-aged adults around 50 years, declining in both younger and older groups.[65] Adults aged 50 and older, particularly those with co-occurring substance use disorders or depression, show the highest dependence prevalence.[66] Lower socioeconomic status consistently correlates with increased risk, including higher smoking prevalence, cigarettes per day, and dependence levels, with low educational attainment emerging as the strongest predictor in multivariate analyses.[67][68] This gradient persists across regions and is mediated partly by financial strain, exacerbating persistence among lower-income groups.[69][70]Health Impacts

Acute and Chronic Effects of Nicotine Exposure

Acute exposure to nicotine activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems, triggering the release of neurotransmitters including dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway, norepinephrine, and serotonin, which elicit sensations of pleasure, heightened alertness, and relaxation.[71] This activation enhances cognitive functions such as fine motor skills, alerting attention, and working memory, as evidenced by meta-analyses of human studies involving non-smokers and satiated smokers.[71] Cardiovascularly, nicotine acutely elevates heart rate, blood pressure, and cardiac contractility through catecholamine release and sympathetic nervous system stimulation, while inducing vasoconstriction in skin and diseased coronary arteries, reducing heart rate variability, and impairing endothelial function.[72] Respiratory responses include bronchoconstriction and increased airway resistance mediated by vagal reflexes.[73] At higher doses, acute effects may manifest as nausea, tremors, or gastrointestinal disturbances.[73] Chronic nicotine exposure leads to nAChR desensitization and upregulation, fostering tolerance and dependence by persistently elevating midbrain dopamine neuron firing rates and altering reward processing circuits.[46] Behaviorally, this manifests as biased decision-making favoring high-reward exploitation over exploratory choices, as observed in preclinical models.[46] Cardiovascular risks include modest increases in fatal myocardial infarction and stroke incidence, heightened mortality in those with ischemic heart disease, and sustained elevations in arterial stiffness, endothelial dysfunction, and blood pressure due to ongoing oxidative stress and vascular remodeling.[72][73] Neurologically, long-term effects encompass neuronal apoptosis, DNA damage, and GABAergic inhibition desensitization, potentially exacerbating addiction vulnerability.[73] Respiratory impacts involve elastin degradation contributing to emphysema-like changes, alongside associations with carcinogenesis through mechanisms like nitrosamine promotion, though these are less pronounced without combustion byproducts.[73] Overall, while acute effects are predominantly stimulatory, chronic exposure amplifies dependence and subtle organ-specific toxicities, with cardiovascular burdens evident but attenuated relative to smoked tobacco delivery.[72]Risks Differentiated by Delivery Method

The health risks associated with nicotine dependence are profoundly influenced by the delivery method, as nicotine itself primarily drives addiction through its effects on dopamine release and reward pathways, while co-occurring toxins, absorption rates, and exposure patterns determine additional morbidity. Inhaled combustible tobacco, such as cigarettes, poses the greatest overall risks due to pyrolysis products including tar, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and nitrosamines, which cause oxidative stress, inflammation, and DNA damage leading to lung cancer (relative risk 15-30 times higher than non-smokers), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease.[24] Rapid pulmonary absorption enhances dependence liability, with peak plasma levels within seconds, reinforcing habitual use.[74] Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), or vaping devices, deliver aerosolized nicotine without combustion, resulting in substantially lower levels of harmful constituents compared to cigarette smoke—typically 95% fewer toxins per standardized assays—reducing risks of respiratory carcinogenesis and emphysema, though acute effects like bronchial irritation and potential for e-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) persist, particularly with adulterated formulations containing vitamin E acetate.[75] Nicotine pharmacokinetics remain rapid via inhalation, sustaining high dependence potential similar to smoking, with cardiovascular strain from elevated heart rate and blood pressure; long-term data indicate vaping confers lower myocardial infarction risk than traditional smoking but elevates it relative to non-use.[76] Aerosol may include volatile organic compounds and metals from heating elements, contributing to endothelial dysfunction.[77] Smokeless tobacco products, including chewing tobacco and snus, avoid inhalation risks but introduce localized oral exposures to tobacco-specific nitrosamines, elevating squamous cell carcinoma odds (up to 50-fold for certain sites) and leukoplakia, alongside gingival recession and pancreatic cancer associations.[74] Systemic nicotine absorption is slower and less efficient than inhalation, potentially moderating dependence intensity compared to smoking, though chronic use still correlates with hypertension and insulin resistance; population studies in Sweden link snus to lower lung disease incidence but persistent cardiovascular hazards.[24] Nicotine replacement therapies (NRT), such as transdermal patches, gums, and lozenges, isolate nicotine delivery without tobacco or combustion byproducts, minimizing cancer and pulmonary risks while providing controlled dosing to mitigate withdrawal; adverse events are mild, including dermatological reactions (10-20% for patches) and gastrointestinal upset (5-10% for oral forms), with negligible evidence of serious toxicity at therapeutic levels.[78] Slower absorption profiles reduce reinforcement compared to inhaled methods, aiding cessation, though prolonged unsupervised use can perpetuate dependence without the multiplicative harms of tobacco vectors.[79]| Delivery Method | Primary Risks Beyond Dependence | Relative Harm Level (vs. Smoking) | Key Pharmacokinetic Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combustible Smoking | Carcinogens, tar-induced COPD, CVD acceleration | Baseline (highest) | Rapid inhalation peak |

| Vaping/ENDS | Aerosol irritants, metals, acute lung injury | Lower (e.g., 5-10% toxin exposure) | Rapid but reduced bolus |

| Smokeless Tobacco | Oral cancers, gum disease | Intermediate (no respiratory) | Slower mucosal uptake |

| NRT | Local irritation, minor CV effects | Lowest (controlled, pure nicotine) | Gradual systemic release |