Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Health professional

View on WikipediaA health professional, healthcare professional (HCP), or healthcare worker (sometimes abbreviated as HCW)[1] is a provider of health care treatment and advice based on formal training and experience. The field includes those who work as a nurse, physician (such as family physician, internist, obstetrician, psychiatrist, radiologist, surgeon etc.), physician assistant, registered dietitian, veterinarian, veterinary technician, optometrist, pharmacist, pharmacy technician, medical assistant, physical therapist, occupational therapist, dentist, midwife, psychologist, audiologist, or healthcare scientist, or who perform services in allied health professions. Experts in public health and community health are also health professionals.

Fields

[edit]

The healthcare workforce comprises a wide variety of professions and occupations who provide some type of healthcare service, including such direct care practitioners as physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, respiratory therapists, dentists, pharmacists, speech-language pathologist, physical therapists, occupational therapists, physical and behavior therapists, as well as allied health professionals such as phlebotomists, medical laboratory scientists, dieticians, and social workers. They often work in hospitals, healthcare centers and other service delivery points, but also in academic training, research, and administration. Some provide care and treatment services for patients in private homes. Many countries have a large number of community health workers who work outside formal healthcare institutions. Managers of healthcare services, health information technicians, and other assistive personnel and support workers are also considered a vital part of health care teams.[2]

Healthcare practitioners are commonly grouped into health professions. Within each field of expertise, practitioners are often classified according to skill level and skill specialization. "Health professionals" are highly skilled workers, in professions that usually require extensive knowledge including university-level study leading to the award of a first degree or higher qualification.[3] This category includes physicians, physician assistants, registered nurses, veterinarians, veterinary technicians, veterinary assistants, dentists, midwives, radiographers, pharmacists, physiotherapists, optometrists, operating department practitioners and others. Allied health professionals, also referred to as "health associate professionals" in the International Standard Classification of Occupations, support implementation of health care, treatment and referral plans usually established by medical, nursing, respiratory care, and other health professionals, and usually require formal qualifications to practice their profession. In addition, unlicensed assistive personnel assist with providing health care services as permitted.[citation needed]

Another way to categorize healthcare practitioners is according to the sub-field in which they practice, such as mental health care, pregnancy and childbirth care, surgical care, rehabilitation care, or public health.[citation needed]

Mental health

[edit]A mental health professional is a health worker who offers services to improve the mental health of individuals or treat mental illness. These include psychiatrists, psychiatry physician assistants, clinical, counseling, and school psychologists, occupational therapists, clinical social workers, psychiatric-mental health nurse practitioners, marriage and family therapists, mental health counselors, as well as other health professionals and allied health professions. These health care providers often deal with the same illnesses, disorders, conditions, and issues; however, their scope of practice often differs. The most significant difference across categories of mental health practitioners is education and training.[4] There are many damaging effects to the health care workers. Many have had diverse negative psychological symptoms ranging from emotional trauma to very severe anxiety. Health care workers have not been treated right and because of that their mental, physical, and emotional health has been affected by it. The SAGE author's said that there were 94% of nurses that had experienced at least one PTSD after the traumatic experience. Others have experienced nightmares, flashbacks, and short and long term emotional reactions.[5] The abuse is causing detrimental effects on these health care workers. Violence is causing health care workers to have a negative attitude toward work tasks and patients, and because of that they are "feeling pressured to accept the order, dispense a product, or administer a medication".[6] Sometimes it can range from verbal to sexual to physical harassment, whether the abuser is a patient, patient's families, physician, supervisors, or nurses.[citation needed]

Obstetrics

[edit]A maternal and newborn health practitioner is a health care expert who deals with the care of women and their children before, during and after pregnancy and childbirth. Such health practitioners include obstetricians, physician assistants, midwives, obstetrical nurses and many others. One of the main differences between these professions is in the training and authority to provide surgical services and other life-saving interventions.[7] In some developing countries, traditional birth attendants, or traditional midwives, are the primary source of pregnancy and childbirth care for many women and families, although they are not certified or licensed. According to research, rates for unhappiness among obstetrician-gynecologists (Ob-Gyns) range somewhere between 40 and 75 percent.[8]

Geriatrics

[edit]A geriatric care practitioner plans and coordinates the care of the elderly and/or disabled to promote their health, improve their quality of life, and maintain their independence for as long as possible.[9] They include geriatricians, occupational therapists, physician assistants, adult-gerontology nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, geriatric clinical pharmacists, geriatric nurses, geriatric care managers, geriatric aides, nursing aides, caregivers and others who focus on the health and psychological care needs of older adults.[citation needed]

Surgery

[edit]A surgical practitioner is a healthcare professional and expert who specializes in the planning and delivery of a patient's perioperative care, including during the anaesthetic, surgical and recovery stages. They may include general and specialist surgeons, physician assistants, assistant surgeons, surgical assistants, veterinary surgeons, veterinary technicians. anesthesiologists, anesthesiologist assistants, nurse anesthetists, surgical nurses, clinical officers, operating department practitioners, anaesthetic technicians, perioperative nurses, surgical technologists, and others.[citation needed]

Rehabilitation

[edit]A rehabilitation care practitioner is a health worker who provides care and treatment which aims to enhance and restore functional ability and quality of life to those with physical impairments or disabilities. These include physiatrists, physician assistants, rehabilitation nurses, clinical nurse specialists, nurse practitioners, physiotherapists, chiropractors, orthotists, prosthetists, occupational therapists, recreational therapists, audiologists, speech and language pathologists, respiratory therapists, rehabilitation counsellors, physical rehabilitation therapists, athletic trainers, physiotherapy technicians, orthotic technicians, prosthetic technicians, personal care assistants, and others.[10]

Optometry

[edit]Optometry is a field traditionally associated with the correction of refractive errors using glasses or contact lenses, and treating eye diseases. Optometrists also provide general eye care, including screening exams for glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy and management of routine or eye conditions. Optometrists may also undergo further training in order to specialize in various fields, including glaucoma, medical retina, low vision, or paediatrics. In some countries, such as the United Kingdom, United States, and Canada, Optometrists may also undergo further training in order to be able to perform some surgical procedures.

Diagnostics

[edit]Medical diagnosis providers are health workers responsible for the process of determining which disease or condition explains a person's symptoms and signs. It is most often referred to as diagnosis with the medical context being implicit. This usually involves a team of healthcare providers in various diagnostic units. These include radiographers, radiologists, Sonographers, medical laboratory scientists, pathologists, and related professionals.[citation needed]

Dentistry

[edit]

A dental care practitioner is a health worker and expert who provides care and treatment to promote and restore oral health. These include dentists and dental surgeons, dental assistants, dental auxiliaries, dental hygienists, dental nurses, dental technicians, dental therapists or oral health therapists, and related professionals.

Podiatry

[edit]Care and treatment for the foot, ankle, and lower leg may be delivered by podiatrists, chiropodists, pedorthists, foot health practitioners, podiatric medical assistants, podiatric nurse and others.

Public health

[edit]A public health practitioner focuses on improving health among individuals, families and communities through the prevention and treatment of diseases and injuries, surveillance of cases, and promotion of healthy behaviors. This category includes community and preventive medicine specialists, physician assistants, public health nurses, pharmacist, clinical nurse specialists, dietitians, environmental health officers (public health inspectors), paramedics, epidemiologists, public health dentists, and others.[citation needed]

Alternative medicine

[edit]In many societies, practitioners of alternative medicine have contact with a significant number of people, either as integrated within or remaining outside the formal health care system. These include practitioners in acupuncture, Ayurveda, herbalism, homeopathy, naturopathy, Reiki, Shamballa Reiki energy healing Archived 2021-01-25 at the Wayback Machine, Siddha medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, traditional Korean medicine, Unani, and Yoga. In some countries such as Canada, chiropractors and osteopaths (not to be confused with doctors of osteopathic medicine in the United States) are considered alternative medicine practitioners.

Occupational hazards

[edit]

The healthcare workforce faces unique health and safety challenges and is recognized by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as a priority industry sector in the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA) to identify and provide intervention strategies regarding occupational health and safety issues.[11]

Biological hazards

[edit]Exposure to respiratory infectious diseases like tuberculosis (caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and influenza can be reduced with the use of respirators; this exposure is a significant occupational hazard for health care professionals.[12] Healthcare workers are also at risk for diseases that are contracted through extended contact with a patient, including scabies.[13] Health professionals are also at risk for contracting blood-borne diseases like hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS through needlestick injuries or contact with bodily fluids.[14][15] This risk can be mitigated with vaccination when there is a vaccine available, like with hepatitis B.[15] In epidemic situations, such as the 2014–2016 West African Ebola virus epidemic or the 2003 SARS outbreak, healthcare workers are at even greater risk, and were disproportionately affected in both the Ebola and SARS outbreaks.[16]

In general, appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) is the first-line mode of protection for healthcare workers from infectious diseases. For it to be effective against highly contagious diseases, personal protective equipment must be watertight and prevent the skin and mucous membranes from contacting infectious material. Different levels of personal protective equipment created to unique standards are used in situations where the risk of infection is different. Practices such as triple gloving and multiple respirators do not provide a higher level of protection and present a burden to the worker, who is additionally at increased risk of exposure when removing the PPE. Compliance with appropriate personal protective equipment rules may be difficult in certain situations, such as tropical environments or low-resource settings. A 2020 Cochrane systematic review found low-quality evidence that using more breathable fabric in PPE, double gloving, and active training reduce the risk of contamination but that more randomized controlled trials are needed for how best to train healthcare workers in proper PPE use.[16]

Tuberculosis screening, testing, and education

[edit]Based on recommendations from The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for TB screening and testing the following best practices should be followed when hiring and employing Health Care Personnel.[17]

When hiring Health Care Personnel, the applicant should complete the following:[18] a TB risk assessment,[19] a TB symptom evaluation for at least those listed on the Signs & Symptoms page,[20] a TB test in accordance with the guidelines for Testing for TB Infection,[21] and additional evaluation for TB disease as needed (e.g. chest x-ray for HCP with a positive TB test)[18] The CDC recommends either a blood test, also known as an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA), or a skin test, also known as a Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST).[21] A TB blood test for baseline testing does not require two-step testing. If the skin test method is used to test HCP upon hire, then two-step testing should be used. A one-step test is not recommended.[18]

The CDC has outlined further specifics on recommended testing for several scenarios.[22] In summary:

- Previous documented positive skin test (TST) then a further TST is not recommended

- Previous documented negative TST within 12 months before employment OR at least two documented negative TSTs ever then a single TST is recommended

- All other scenarios, with the exception of programs using blood tests, the recommended testing is a two-step TST

According to these recommended testing guidelines any two negative TST results within 12 months of each other constitute a two-step TST.

For annual screening, testing, and education, the only recurring requirement for all HCP is to receive TB education annually.[18] While the CDC offers education materials, there is not a well defined requirement as to what constitutes a satisfactory annual education. Annual TB testing is no longer recommended unless there is a known exposure or ongoing transmission at a healthcare facility. Should an HCP be considered at increased occupational risk for TB annual screening may be considered. For HCP with a documented history of a positive TB test result do not need to be re-tested but should instead complete a TB symptom evaluation. It is assumed that any HCP who has undergone a chest x-ray test has had a previous positive test result. When considering mental health you may see your doctor to be evaluated at your digression. It is recommended to see someone at least once a year in order to make sure that there has not been any sudden changes.[23]

Psychosocial hazards

[edit]Occupational stress and occupational burnout are highly prevalent among health professionals.[24] Some studies suggest that workplace stress is pervasive in the health care industry because of inadequate staffing levels, long work hours, exposure to infectious diseases and hazardous substances leading to illness or death, and in some countries threat of malpractice litigation. Other stressors include the emotional labor of caring for ill people and high patient loads. The consequences of this stress can include substance abuse, suicide, major depressive disorder, and anxiety, all of which occur at higher rates in health professionals than the general working population. Elevated levels of stress are also linked to high rates of burnout, absenteeism and diagnostic errors, and reduced rates of patient satisfaction.[25] In Canada, a national report (Canada's Health Care Providers) also indicated higher rates of absenteeism due to illness or disability among health care workers compared to the rest of the working population, although those working in health care reported similar levels of good health and fewer reports of being injured at work.[26]

There is some evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation training and therapy (including meditation and massage), and modifying schedules can reduce stress and burnout among multiple sectors of health care providers. Research is ongoing in this area, especially with regards to physicians, whose occupational stress and burnout is less researched compared to other health professions.[27]

Healthcare workers are at higher risk of on-the-job injury due to violence. Drunk, confused, and hostile patients and visitors are a continual threat to providers attempting to treat patients. Frequently, assault and violence in a healthcare setting goes unreported and is wrongly assumed to be part of the job.[28] Violent incidents typically occur during one-on-one care; being alone with patients increases healthcare workers' risk of assault.[29] In the United States, healthcare workers experience 2⁄3 of nonfatal workplace violence incidents.[28] Psychiatric units represent the highest proportion of violent incidents, at 40%; they are followed by geriatric units (20%) and the emergency department (10%). Workplace violence can also cause psychological trauma.[29]

Health care professionals are also likely to experience sleep deprivation due to their jobs. Many health care professionals are on a shift work schedule, and therefore experience misalignment of their work schedule and their circadian rhythm. In 2007, 32% of healthcare workers were found to get fewer than 6 hours of sleep a night. Sleep deprivation also predisposes healthcare professionals to make mistakes that may potentially endanger a patient.[30]

COVID pandemic

[edit]Especially in times like the present (2020), the hazards of health professional stem into the mental health. Research from the last few months highlights that COVID-19 has contributed greatly to the degradation of mental health in healthcare providers. This includes, but is not limited to, anxiety, depression/burnout, and insomnia.[citation needed]

A study done by Di Mattei et al. (2020) revealed that 12.63% of COVID nurses and 16.28% of other COVID healthcare workers reported extremely severe anxiety symptoms at the peak of the pandemic.[31] In addition, another study was conducted on 1,448 full time employees in Japan. The participants were surveyed at baseline in March 2020 and then again in May 2020. The result of the study showed that psychological distress and anxiety had increased more among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak.[32]

Similarly, studies have also shown that following the pandemic, at least one in five healthcare professionals report symptoms of anxiety.[33] Specifically, the aspect of "anxiety was assessed in 12 studies, with a pooled prevalence of 23.2%" following COVID.[33] When considering all 1,448 participants that percentage makes up about 335 people.

Abuse by patients

[edit]- The patients are selecting victims who are more vulnerable. For example, Cho said that these would be the nurses that are lacking experience or trying to get used to their new roles at work.[34]

- Others authors that agree with this are Vento, Cainelli, & Vallone and they said that, the reason patients have caused danger to health care workers is because of insufficient communication between them, long waiting lines, and overcrowding in waiting areas.[35] When patients are intrusive and/or violent toward the faculty, this makes the staff question what they should do about taking care of a patient.

- There have been many incidents from patients that have really caused some health care workers to be traumatized and have so much self doubt. Goldblatt and other authors said that there was a lady who was giving birth, her husband said, "Who is in charge around here"? "Who are these sluts you employ here".[5] This was very avoidable to have been said to the people who are taking care of your wife and child.

Physical and chemical hazards

[edit]Slips, trips, and falls are the second-most common cause of worker's compensation claims in the US and cause 21% of work absences due to injury. These injuries most commonly result in strains and sprains; women, those older than 45, and those who have been working less than a year in a healthcare setting are at the highest risk.[36]

An epidemiological study published in 2018 examined the hearing status of noise-exposed health care and social assistance (HSA) workers sector to estimate and compare the prevalence of hearing loss by subsector within the sector. Most of the HSA subsector prevalence estimates ranged from 14% to 18%, but the Medical and Diagnostic Laboratories subsector had 31% prevalence and the Offices of All Other Miscellaneous Health Practitioners had a 24% prevalence. The Child Day Care Services subsector also had a 52% higher risk than the reference industry.[37]

Exposure to hazardous drugs, including those for chemotherapy, is another potential occupational risk. These drugs can cause cancer and other health conditions.[38]

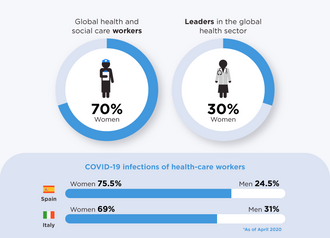

Gender factors

[edit]Female health care workers may face specific types of workplace-related health conditions and stress. According to the World Health Organization, women predominate in the formal health workforce in many countries and are prone to musculoskeletal injury (caused by physically demanding job tasks such as lifting and moving patients) and burnout. Female health workers are exposed to hazardous drugs and chemicals in the workplace which may cause adverse reproductive outcomes such as spontaneous abortion and congenital malformations. In some contexts, female health workers are also subject to gender-based violence from coworkers and patients.[39][40]

Workforce shortages

[edit]Many jurisdictions report shortfalls in the number of trained health human resources to meet population health needs and/or service delivery targets, especially in medically underserved areas. For example, in the United States, the 2010 federal budget invested $330 million to increase the number of physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, and dentists practicing in areas of the country experiencing shortages of trained health professionals. The Budget expands loan repayment programs for physicians, nurses, and dentists who agree to practice in medically underserved areas. This funding will enhance the capacity of nursing schools to increase the number of nurses. It will also allow states to increase access to oral health care through dental workforce development grants. The Budget's new resources will sustain the expansion of the health care workforce funded in the Recovery Act.[41] There were 15.7 million health care professionals in the US as of 2011.[36]

In Canada, the 2011 federal budget announced a Canada Student Loan forgiveness program to encourage and support new family physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and nurses to practice in underserved rural or remote communities of the country, including communities that provide health services to First Nations and Inuit populations.[42]

In Uganda, the Ministry of Health reports that as many as 50% of staffing positions for health workers in rural and underserved areas remain vacant. As of early 2011, the Ministry was conducting research and costing analyses to determine the most appropriate attraction and retention packages for medical officers, nursing officers, pharmacists, and laboratory technicians in the country's rural areas.[43]

At the international level, the World Health Organization estimates a shortage of almost 4.3 million doctors, midwives, nurses, and support workers worldwide to meet target coverage levels of essential primary health care interventions.[44] The shortage is reported most severe in 57 of the poorest countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Nurses are the most common type of medical field worker to face shortages around the world. There are numerous reasons that the nursing shortage occurs globally. Some include: inadequate pay, a large percentage of working nurses are over the age of 45 and are nearing retirement age, burnout, and lack of recognition.[45]

Incentive programs have been put in place to aid in the deficit of pharmacists and pharmacy students. The reason for the shortage of pharmacy students is unknown but one can infer that it is due to the level of difficulty in the program.[46]

Results of nursing staff shortages can cause unsafe staffing levels that lead to poor patient care. Five or more incidents that occur per day in a hospital setting as a result of nurses who do not receive adequate rest or meal breaks is a common issue.[47]

Regulation and registration

[edit]Practicing without a license that is valid and current is typically illegal. In most jurisdictions, the provision of health care services is regulated by the government. Individuals found to be providing medical, nursing or other professional services without the appropriate certification or license may face sanctions and criminal charges leading to a prison term. The number of professions subject to regulation, requisites for individuals to receive professional licensure, and nature of sanctions that can be imposed for failure to comply vary across jurisdictions.

In the United States, under Michigan state laws, an individual is guilty of a felony if identified as practicing in the health profession without a valid personal license or registration. Health professionals can also be imprisoned if found guilty of practicing beyond the limits allowed by their licenses and registration. The state laws define the scope of practice for medicine, nursing, and a number of allied health professions.[48][unreliable source?] In Florida, practicing medicine without the appropriate license is a crime classified as a third degree felony,[49] which may give imprisonment up to five years. Practicing a health care profession without a license which results in serious bodily injury classifies as a second degree felony,[49] providing up to 15 years' imprisonment.

In the United Kingdom, healthcare professionals are regulated by the state; the UK Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) protects the 'title' of each profession it regulates. For example, it is illegal for someone to call himself an Occupational Therapist or Radiographer if they are not on the register held by the HCPC.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "HCWs With Long COVID Report Doubt, Disbelief From Colleagues". Medscape. 29 November 2021.

- ^ World Health Organization, 2006. World Health Report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: WHO.

- ^ "Classifying health workers" (PDF). World Health Organization. Geneva. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-08-16. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- ^ "Difference Between Psychologists and Psychiatrists". Psychology.about.com. 2007. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- ^ a b Goldblatt, Hadass; Freund, Anat; Drach-Zahavy, Anat; Enosh, Guy; Peterfreund, Ilana; Edlis, Neomi (2020-05-01). "Providing Health Care in the Shadow of Violence: Does Emotion Regulation Vary Among Hospital Workers From Different Professions?". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 35 (9–10): 1908–1933. doi:10.1177/0886260517700620. ISSN 0886-2605. PMID 29294693. S2CID 19304885.

- ^ Johnson, Cheryl L.; DeMass Martin, Suzanne L.; Markle-Elder, Sara (April 2007). "Stopping Verbal Abuse in the Workplace". American Journal of Nursing. 107 (4): 32–34. doi:10.1097/01.naj.0000271177.59574.c5. ISSN 0002-936X. PMID 17413727.

- ^ Gupta N et al. "Human resources for maternal, newborn and child health: from measurement and planning to performance for improved health outcomes. Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine Human Resources for Health, 2011, 9(16). Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "Ob-Gyn Burnout: Why So Many Doctors Are Questioning Their Calling". healthecareers.com. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ Araujo de Carvalho, Islene; Epping-Jordan, JoAnne; Pot, Anne Margriet; Kelley, Edward; Toro, Nuria; Thiyagarajan, Jotheeswaran A; Beard, John R (2017-11-01). "Organizing integrated health-care services to meet older people's needs". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 95 (11): 756–763. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.187617. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 5677611. PMID 29147056.

- ^ Gupta N et al. "Health-related rehabilitation services: assessing the global supply of and need for human resources." Archived 2012-07-20 at the Wayback Machine BMC Health Services Research, 2011, 11:276. Published 17 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "National Occupational Research Agenda for Healthcare and Social Assistance | NIOSH | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-02-15. Retrieved 2019-03-14.

- ^ Bergman, Michael; Zhuang, Ziqing; Shaffer, Ronald E. (25 July 2013). "Advanced Headforms for Evaluating Respirator Fit". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ FitzGerald, Deirdre; Grainger, Rachel J.; Reid, Alex (2014). "Interventions for preventing the spread of infestation in close contacts of people with scabies". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (2) CD009943. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009943.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10819104. PMID 24566946.

- ^ Cunningham, Thomas; Burnett, Garrett (17 May 2013). "Does your workplace culture help protect you from hepatitis?". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ a b Reddy, Viraj K; Lavoie, Marie-Claude; Verbeek, Jos H; Pahwa, Manisha (14 November 2017). "Devices for preventing percutaneous exposure injuries caused by needles in healthcare personnel". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (11) CD009740. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009740.pub3. PMC 6491125. PMID 29190036.

- ^ a b Verbeek, Jos H.; Rajamaki, Blair; Ijaz, Sharea; Sauni, Riitta; Toomey, Elaine; Blackwood, Bronagh; Tikka, Christina; Ruotsalainen, Jani H.; Kilinc Balci, F. Selcen (May 15, 2020). "Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (5) CD011621. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011621.pub5. hdl:1983/b7069408-3bf6-457a-9c6f-ecc38c00ee48. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8785899. PMID 32412096. S2CID 218649177.

- ^ Sosa, Lynn E. (April 2, 2019). "Tuberculosis Screening, Testing, and Treatment of U.S. Health Care Personnel: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (19): 439–443. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6819a3. PMC 6522077. PMID 31099768.

- ^ a b c d "Testing Health Care Workers | Testing & Diagnosis | TB | CDC". www.cdc.gov. March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Health Care Personnel (HCP) Baseline Individual TB Risk Assessment" (PDF). cdc.gov. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "Signs & Symptoms | Basic TB Facts | TB | CDC". www.cdc.gov. February 4, 2021.

- ^ a b "Testing for TB Infection | Testing & Diagnosis | TB | CDC". www.cdc.gov. March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Guidelines for Preventing the Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Health-Care Settings, 2005". www.cdc.gov.

- ^ Spoorthy, Mamidipalli Sai; Pratapa, Sree Karthik; Mahant, Supriya (June 2020). "Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic–A review". Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 51 102119. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119. PMC 7175897. PMID 32339895.

- ^ Ruotsalainen, Jani H.; Verbeek, Jos H.; Mariné, Albert; Serra, Consol (2015-04-07). "Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4) CD002892. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6718215. PMID 25847433.

- ^ "Exposure to Stress: Occupational Hazards in Hospitals". NIOSH Publication No. 2008–136 (July 2008). 2 December 2008. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2008136. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008.

- ^ Canada's Health Care Providers, 2007 (Report). Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

- ^ Ruotsalainen, JH; Verbeek, JH; Mariné, A; Serra, C (7 April 2015). "Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4) CD002892. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub5. PMC 6718215. PMID 25847433.

- ^ a b Hartley, Dan; Ridenour, Marilyn (12 August 2013). "Free On-line Violence Prevention Training for Nurses". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ a b Hartley, Dan; Ridenour, Marilyn (September 13, 2011). "Workplace Violence in the Healthcare Setting". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH. Archived from the original on February 8, 2014.

- ^ Caruso, Claire C. (August 2, 2012). "Running on Empty: Fatigue and Healthcare Professionals". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013.

- ^ Di Mattei, Valentina; Perego, Gaia; Milano, Francesca; Mazzetti, Martina; Taranto, Paola; Di Pierro, Rossella; De Panfilis, Chiara; Madeddu, Fabio; Preti, Emanuele (2021-05-15). "The "Healthcare Workers' Wellbeing (Benessere Operatori)" Project: A Picture of the Mental Health Conditions of Italian Healthcare Workers during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (10): 5267. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105267. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 8156728. PMID 34063421.

- ^ Sasaki, Natsu; Kuroda, Reiko; Tsuno, Kanami; Kawakami, Norito (2020-11-01). "The deterioration of mental health among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak: A population-based cohort study of workers in Japan". Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 46 (6): 639–644. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3922. ISSN 0355-3140. PMC 7737801. PMID 32905601.

- ^ a b Pappa, Sofia; Ntella, Vasiliki; Giannakas, Timoleon; Giannakoulis, Vassilis G.; Papoutsi, Eleni; Katsaounou, Paraskevi (August 2020). "Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 88: 901–907. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. PMC 7206431. PMID 32437915.

- ^ Cho, Hyeonmi; Pavek, Katie; Steege, Linsey (2020-07-22). "Workplace verbal abuse, nurse-reported quality of care and patient safety outcomes among early-career hospital nurses". Journal of Nursing Management. 28 (6): 1250–1258. doi:10.1111/jonm.13071. ISSN 0966-0429. PMID 32564407. S2CID 219972442.

- ^ Vento, Sandro; Cainelli, Francesca; Vallone, Alfredo (2020-09-18). "Violence Against Healthcare Workers: A Worldwide Phenomenon With Serious Consequences". Frontiers in Public Health. 8 570459. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.570459. ISSN 2296-2565. PMC 7531183. PMID 33072706.

- ^ a b Collins, James W.; Bell, Jennifer L. (June 11, 2012). "Slipping, Tripping, and Falling at Work". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012.

- ^ Masterson, Elizabeth A.; Themann, Christa L.; Calvert, Geoffrey M. (2018-04-15). "Prevalence of Hearing Loss Among Noise-Exposed Workers Within the Health Care and Social Assistance Sector, 2003 to 2012". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 60 (4): 350–356. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001214. ISSN 1076-2752. PMID 29111986. S2CID 4637417.

- ^ Connor, Thomas H. (March 7, 2011). "Hazardous Drugs in Healthcare". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012.

- ^ World Health Organization. Women and health: today's evidence, tomorrow's agenda. Archived 2012-12-25 at the Wayback Machine Geneva, 2009. Retrieved on March 9, 2011.

- ^ Swanson, Naomi; Tisdale-Pardi, Julie; MacDonald, Leslie; Tiesman, Hope M. (13 May 2013). "Women's Health at Work". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved 2009-03-06 – via National Archives.

- ^ Government of Canada. 2011. Canada's Economic Action Plan: Forgiving Loans for New Doctors and Nurses in Under-Served Rural and Remote Areas. Ottawa, 22 March 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Rockers P et al. Determining Priority Retention Packages to Attract and Retain Health Workers in Rural and Remote Areas in Uganda. Archived 2011-05-23 at the Wayback Machine CapacityPlus Project. February 2011.

- ^ "The World Health Report 2006 - Working together for health". Geneva: WHO: World Health Organization. 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-02-28.

- ^ Mefoh, Philip Chukwuemeka; Ude, Eze Nsi; Chukwuorji, JohBosco Chika (2019-01-02). "Age and burnout syndrome in nursing professionals: moderating role of emotion-focused coping". Psychology, Health & Medicine. 24 (1): 101–107. doi:10.1080/13548506.2018.1502457. ISSN 1354-8506. PMID 30095287. S2CID 51954488.

- ^ Traynor, Kate (2003-09-15). "Staffing shortages plague nation's pharmacy schools". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 60 (18): 1822–1824. doi:10.1093/ajhp/60.18.1822. ISSN 1079-2082. PMID 14521029.

- ^ Leslie, G. D. (October 2008). "Critical Staffing shortage". Australian Nursing Journal. 16 (4): 16–17. doi:10.1016/s1036-7314(05)80033-5. ISSN 1036-7314. PMID 14692155.

- ^ wiki.bmezine.com --> Practicing Medicine. In turn citing Michigan laws

- ^ a b CHAPTER 2004-256 Committee Substitute for Senate Bill No. 1118 Archived 2011-07-23 at the Wayback Machine State of Florida, Department of State.

External links

[edit]Health professional

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Scope

Core Qualifications and Responsibilities

Health professionals are distinguished by their possession of formal qualifications, typically including completion of accredited educational programs tailored to their specific field, such as associate, bachelor's, master's, or doctoral degrees depending on the role. For physicians, this entails earning a Doctor of Medicine (MD) or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) degree from an accredited medical school, followed by residency training lasting 3-7 years.[13] Registered nurses must complete an approved nursing program, often culminating in a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN), and pass the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX-RN).[14] Dentists require a Doctor of Dental Surgery (DDS) or Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD) degree, including clinical training and passage of the National Board Dental Examinations (NBDE).[15] These educational pathways emphasize foundational sciences, clinical skills, and evidence-based practices to ensure competency in diagnosing, treating, and preventing health conditions.[1] Licensure or certification constitutes a core qualification, granted by governmental or professional regulatory bodies after verifying education, passing standardized examinations, and often completing supervised practice or background checks. In the United States, state medical boards oversee physician licensure, requiring ongoing verification of moral character and fitness to practice.[13] Similar processes apply to other professions, such as nursing boards for RNs and dental boards for dentists, with requirements varying by jurisdiction but universally aimed at public protection through minimum competency standards.[16] International classifications, such as those from the World Health Organization aligned with the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO), categorize health professionals by skill levels (e.g., requiring tertiary education for advanced roles) and specialization to facilitate global workforce planning.[2] Key responsibilities encompass delivering patient-centered care, which involves assessing health needs, formulating evidence-based interventions, and coordinating treatments while respecting patient values and preferences.[7] Health professionals must adhere to ethical principles including beneficence (promoting well-being), nonmaleficence (avoiding harm), autonomy (honoring patient choices), and justice (ensuring fair resource allocation).[17] This includes maintaining confidentiality of health information, obtaining informed consent, and reporting communicable diseases or abuse as mandated by law.[18] They are also obligated to engage in interprofessional collaboration, utilizing informatics for accurate record-keeping, and pursuing continuous quality improvement through evidence review and professional development.[7] In practice, responsibilities extend to health promotion and prevention, such as conducting screenings, educating patients on lifestyle factors, and contributing to public health efforts amid varying scopes defined by licensure (e.g., physicians may prescribe independently, while nurses operate under protocols).[19] Violations of these duties, including incompetence or ethical lapses, can result in disciplinary actions like license suspension by regulatory authorities, underscoring the accountability inherent to the profession.[16]Distinctions from Paraprofessionals and Lay Caregivers

Health professionals are characterized by their extensive formal education, typically requiring three to six years of study at higher educational institutions leading to a degree or advanced qualification, which equips them with the theoretical knowledge and skills for autonomous practice in diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and rehabilitation of health conditions.[3] This level of training enables them to exercise independent judgment, prescribe interventions, and often supervise other health workers, with their practice governed by stringent licensure and regulatory standards enforced by professional boards or government agencies to ensure public safety and accountability.[20] Examples include physicians, registered nurses, and pharmacists, whose scopes of practice are defined by law to encompass high-complexity tasks that carry significant liability.[3] Paraprofessionals, referred to as health associate professionals in international classifications, differ markedly in their preparatory requirements and operational constraints, relying on shorter tertiary-level training, certification programs, or extended on-the-job experience rather than full degrees.[3] Their roles are supportive and technical, such as assisting in patient monitoring, basic procedures, or administrative tasks under the direct oversight of licensed professionals, with scopes of practice explicitly limited to prevent independent clinical decision-making that could pose risks without advanced expertise.[21] Unlike health professionals, paraprofessionals are generally not credentialed as primary healthcare providers and face regulatory boundaries that prohibit diagnosis or prescriptive authority, as seen in roles like nursing aides, medical assistants, or community health workers who must adhere to protocols set by supervising clinicians.[22] This supervised framework reflects a deliberate delineation to leverage their contributions while mitigating potential errors from insufficient foundational knowledge.[3] Lay caregivers represent the least formalized category, consisting of unpaid individuals—often family members, friends, or community volunteers—who deliver personal assistance without any mandated professional education, certification, or regulatory compliance.[23] Their involvement centers on non-clinical support, including help with daily activities, emotional companionship, or basic aftercare in home settings, but lacks the evidence-based training required to handle medical complexities, leading to reliance on guidance from formal providers rather than independent action.[24] Legal frameworks in various jurisdictions recognize lay caregivers for transitional roles post-hospitalization but explicitly distinguish them from regulated personnel by prohibiting any assumption of professional duties, underscoring the absence of accountability mechanisms like malpractice oversight that apply to trained workers.[25] This informal status, while valuable for accessibility, inherently limits their capacity to address causal factors in health outcomes, as their interventions stem from relational bonds rather than systematic skill acquisition.[3]Historical Development

Ancient and Pre-Modern Practices

In ancient Egypt, dating back to the Old Kingdom around 2686–2181 BC, medical practice was conducted by specialized professionals including secular physicians known as swnw and temple priests called wab who integrated religious rituals with empirical treatments. The Ebers Papyrus, composed circa 1550 BC, documents over 700 remedies derived from herbs, minerals, and animal products, alongside procedures such as setting fractures, stitching wounds, and performing minor surgeries like draining abscesses. These practitioners demonstrated advanced anatomical knowledge from mummification practices, enabling interventions for conditions including dental issues and gynecological disorders, though supernatural explanations often coexisted with observable causes.[26][27][28] In classical Greece from the 5th century BC, physicians like Hippocrates of Kos (c. 460–370 BC) shifted toward rational inquiry, rejecting divine causation in favor of environmental and lifestyle factors influencing health, as outlined in the Hippocratic Corpus of approximately 60 treatises. This collection emphasized clinical observation, prognosis, and ethical standards, including the Hippocratic Oath, which bound practitioners to patient confidentiality and non-maleficence without invoking supernatural oaths. Greek healers, often itinerant or school-affiliated, treated imbalances of the four humors—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—through diet, exercise, and purgatives, laying groundwork for separating medicine from priestly roles.[29][30] Parallel developments occurred in ancient India, where Ayurvedic healers emerged from Vedic traditions around 1500–500 BC, evolving into systematic practitioners by the time of texts like the Charaka Samhita (c. 300 BC–200 AD), which detailed diagnostics, surgery, and pharmacology based on dosha balances (vata, pitta, kapha). Sushruta, attributed with the Sushruta Samhita (c. 600 BC), described over 300 surgical procedures including rhinoplasty and cataract extraction using specialized instruments, reflecting empirical skill honed through apprenticeship and dissection of cadavers. These vaidya (physicians) prioritized holistic prevention via diet and herbs, though ritual elements persisted in early phases.[31][32] In ancient China, from the Warring States period (475–221 BC), figures like Bian Que (c. 407–310 BC) practiced diagnostic techniques such as pulse reading and acupuncture, as recorded in texts like the Huangdi Neijing (c. 200 BC), which framed health as harmony between yin-yang and qi flows influenced by environment and diet. Healers, often court physicians or wandering experts, employed moxibustion, herbal decoctions, and needling to restore balance, with state examinations emerging by the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) to standardize competence.[33] During the Roman era and into medieval Europe (c. 500–1500 AD), health professionals included Galen of Pergamon (129–c. 216 AD), whose anatomical dissections and humoral theories dominated until the Renaissance, influencing both elite physicians and practical surgeons. In Europe, university-trained physicians from the 12th century onward focused on theoretical Galenic scholarship and urine analysis, while barber-surgeons handled hands-on tasks like bloodletting, tooth extraction, and amputations, often amid plagues requiring rapid interventions despite limited antisepsis. Guild regulations by the 13th century formalized their roles, separating them from academic medicine but enabling widespread care in rural and urban settings.[34]Industrial Era Professionalization

The Industrial Era, spanning roughly the late 18th to early 20th centuries, witnessed the transition of health practices from artisanal and unregulated pursuits to structured professions characterized by formal education, licensure, and self-governing bodies. This shift was propelled by urbanization, factory-based labor, and epidemiological challenges like cholera outbreaks, which exposed the limitations of folk remedies and itinerant healers. In medicine, practitioners increasingly emphasized empirical observation and scientific methods over Galenic humoral theory, fostering associations to codify standards. The American Medical Association, founded in 1847, advocated for uniform curricula and exclusion of unqualified rivals, amid a proliferation of proprietary schools that numbered over 400 by 1900, many offering minimal training.[35][36] Licensing emerged as a cornerstone of professional control, reversing earlier deregulatory trends rooted in Jacksonian egalitarianism that had eliminated state medical boards in much of the U.S. by the 1830s. By the 1870s, states like Illinois (1877) and others reinstated or enacted laws requiring examinations and diplomas for practice, initially targeting physicians and dentists to curb quackery and ensure anatomical knowledge via dissection mandates. These measures granted legal monopolies, with compliance enforced by boards comprising licensed peers, though enforcement varied and full standardization awaited the 20th century. In Britain, the Medical Act of 1858 established a national registry and General Medical Council to oversee qualifications, reflecting parallel efforts amid industrial health demands.[37][38][39] Nursing underwent parallel formalization, evolving from domestic or religious caregiving to a disciplined occupation. The Crimean War (1853–1856) highlighted sanitary reforms under Florence Nightingale, whose 1860 Notes on Nursing promoted hygiene and training, inspiring hospital-based schools like London's Nightingale School (1860). In the U.S., 1873 saw the opening of three hospital-affiliated training programs in New York, New Haven, and Boston, emphasizing two-year apprenticeships in wards over theoretical lectures, graduating over 150 nurses by 1880. Professional bodies, such as the American Nurses Association's precursors, formed to advocate licensure, though mandatory state laws lagged until the early 1900s. Pharmacy and dentistry followed suit, with the American Pharmaceutical Association (1852) and first dental schools (e.g., Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, 1840) pushing for degree requirements and boards by the 1880s, aligning with broader occupational regulation to prioritize evidence-based competence over empirical self-taught methods.[40][41][39]20th-Century Expansion and Specialization

The Flexner Report, published in 1910 by Abraham Flexner under the Carnegie Foundation, catalyzed the standardization of medical education in the United States and Canada by recommending rigorous scientific curricula, university affiliation for medical schools, and clinical training in hospitals, resulting in the closure of over half of the 155 existing medical schools by 1923 and elevating the profession's scientific basis.[42] This reform shifted physician training from proprietary, often substandard institutions to evidence-based models, fostering a more competent workforce amid rising demands from urbanization and infectious diseases.[43] Specialization accelerated post-World War I, driven by technological innovations like X-rays (discovered 1895) and antibiotics (penicillin isolated 1928, widely used by 1940s), which enabled targeted interventions beyond general practice; by 1938-1949, the number of medical specialists increased 96% while general practitioners declined 13%, reflecting a broader trend where specialists comprised over 75% of physician workforce growth from 1980 onward, rooted in mid-century shifts.[44] World War II further propelled this by necessitating rapid training expansions and interdisciplinary teams, with U.S. physician numbers growing from about 150,000 in 1940 to over 300,000 by 1970, accompanied by the formalization of boards certifying specialties like cardiology and neurosurgery.[45] Nursing professionalized concurrently, transitioning from hospital-based apprenticeships to university-linked programs; federal legislation like the 1943 Bolton Act funded cadet nurse corps, training over 50,000 women by 1948 to address wartime shortages, while the 1971 Nurse Training Act supported advanced roles, increasing registered nurses from 300,000 in 1940 to 1.2 million by 1970.[46] Allied health professions emerged mid-century to support complex care, with roles like radiologic technologists and physical therapists formalizing through accreditation post-1940s, as medical advances highlighted needs for diagnostic and rehabilitative expertise, leading to over 200 allied occupations by century's end.[41] Public health training also expanded, with schools producing graduates versed in epidemiology by the 1930s, underpinning preventive specialization amid 20th-century epidemics.[47]Education and Training

Entry-Level Requirements and Pathways

Entry-level requirements for health professionals generally involve completing accredited postsecondary education programs, acquiring clinical experience through internships or supervised practice, and obtaining licensure via standardized examinations to verify competence. In the United States, these pathways are regulated by state licensing boards and national accrediting bodies, with education levels spanning associate degrees for some roles to doctoral degrees for others, reflecting the varying scopes of autonomous practice. Prerequisites often include strong foundational knowledge in biological sciences, chemistry, and mathematics, gained through undergraduate coursework.[19] Physicians pursue a bachelor's degree, typically lasting four years with emphasis on pre-medical sciences, followed by four years of medical school to earn a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.), during which students complete classroom instruction and clinical rotations. Entry into medical school requires competitive scores on the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT). After graduation, candidates must complete residency programs of three to seven years and pass the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) or Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination (COMLEX-USA) for licensure in all states.[48] Registered nurses enter the profession via three primary paths: a two-year Associate Degree in Nursing (ADN) from a community college, a four-year Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) from a university, or a hospital-based diploma program. All paths require passing the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN) for state licensure, with BSN holders often preferred for advancement due to broader preparation in leadership and research.[14] Pharmacists complete at least two years of undergraduate prerequisite courses before entering a four-year Doctor of Pharmacy (Pharm.D.) program, which integrates pharmaceutical sciences, patient care simulations, and experiential rotations. Licensure demands passing the North American Pharmacist Licensure Examination (NAPLEX) assessing drug therapy knowledge and a Multistate Pharmacy Jurisprudence Examination (MPJE) or state-specific law test.[49] Dentists obtain a bachelor's degree followed by a four-year Doctor of Dental Surgery (D.D.S.) or Doctor of Dental Medicine (D.M.D.) from an accredited dental school, including preclinical sciences and clinical practice in restorative and preventive care. State licensure requires passing the National Board Dental Examinations (NBDE) Parts I and II, clinical assessments, and jurisprudence exams, with all states mandating initial certification.[15] Allied health professionals, such as radiologic technologists or respiratory therapists, often begin with an associate degree (two years) or bachelor's degree, incorporating hands-on training in diagnostic procedures or therapeutic interventions, followed by certification from organizations like the American Registry of Radiologic Technologists (ARRT). Licensure varies by state and role but typically involves passing national credentialing exams after program completion.[19]Advanced Training and Specialization

Following completion of entry-level education, health professionals often pursue advanced training to acquire specialized expertise, enabling them to manage complex cases and contribute to subspecialized fields. This phase emphasizes hands-on clinical experience, supervised practice, and rigorous assessment, typically under accreditation bodies such as the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) for physicians or the American Nurses Credentialing Center for advanced nursing roles. Durations and requirements vary by profession and jurisdiction, but the goal is competency in evidence-based interventions, with programs incorporating thousands of supervised patient hours to build procedural proficiency and diagnostic acumen.[50] For physicians, advanced training begins with residency programs post-medical school, lasting 3 to 7 years based on specialty; internal medicine and family medicine residencies require 3 years, general surgery 5 years, and neurosurgery up to 7 years, during which trainees manage increasing autonomy under supervision.[51] Subspecialization follows via ACGME-accredited fellowships, adding 1 to 3 years—for instance, interventional cardiology requires a 3-year fellowship after internal medicine residency—to focus on niche areas like advanced imaging or procedural interventions.[52] These programs prioritize milestones in clinical judgment and patient outcomes, with duty-hour limits enforced to mitigate fatigue-related errors.[53] Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), including nurse practitioners and certified registered nurse anesthetists, must complete a graduate-level master's or doctoral program (e.g., MSN or DNP) after BSN licensure, encompassing at least 500 supervised clinical hours and culminating in national certification exams from bodies like the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners.[54][55] This pathway, spanning 2 to 4 additional years, equips APRNs for independent or collaborative practice in areas like primary care or acute specialties, with state-specific pharmacology and prescriptive authority requirements.[56] In allied health fields, such as physical therapy, specialization involves post-doctoral residencies (typically 12 months) or board certifications in areas like orthopedics, accredited by organizations such as the American Board of Physical Therapy Residency and Fellowship Education.[57] Dentists and pharmacists similarly advance through 1- to 3-year residencies for specialties like oral surgery or clinical pharmacy, focusing on procedural mastery and pharmacotherapeutic optimization.[58]Continuing Education and Recertification

Continuing education for health professionals typically involves accumulating credits through accredited activities such as conferences, online modules, journal reviews, and workshops, aimed at updating knowledge on clinical advancements, guidelines, and best practices.[59] In the United States, most state licensing boards mandate continuing medical education (CME) or equivalent hours for license renewal, often ranging from 20 to 50 credits annually or biennially, with requirements varying by profession and jurisdiction; for instance, physicians in many states must complete at least 40 CME credits every two years.[60] These mandates stem from efforts to mitigate skill obsolescence, though empirical evidence on CME's impact shows modest improvements in physician knowledge and practice behavior in about 60% of evaluated interventions, with weaker support for direct enhancements in patient outcomes due to methodological limitations in studies.[61][62] Recertification processes for specialty board certifications, overseen by bodies like the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), require physicians to engage in ongoing maintenance of certification (MOC), including periodic exams, performance assessments, and patient safety modules, typically on a 10-year cycle with interim requirements every few years to verify competence.[63] For nurses, recertification for licenses often demands 15 to 30 contact hours of continuing education units (CEUs) every two years, alongside proof of active practice; for example, registered nurses in several states must complete 30 hours or equivalent professional development activities biennially, with mandatory topics like infection control.[64] Allied health professionals, such as physical therapists, face similar triennial cycles requiring 24 to 36 hours, emphasizing evidence-based updates to sustain licensure.[65] Failure to comply can result in license suspension, underscoring the regulatory emphasis on lifelong learning despite critiques that rigid credit quotas may prioritize quantity over transformative learning.[66] Internationally, frameworks like the European Union's mutual recognition directives encourage harmonized CE, but implementation varies, with bodies such as the UK's General Medical Council requiring annual appraisals and revalidation every five years based on workplace performance data rather than solely credits. Empirical reviews indicate that multifaceted CE—combining interactive formats with feedback—yields better retention of skills than passive lectures, though overall effectiveness remains constrained by low-quality evidence and inconsistent links to reduced errors or improved care delivery.[67] Health professionals must document activities through accredited providers, with audits enforcing accountability, reflecting a causal link between structured updates and reduced knowledge gaps in rapidly evolving fields like pharmacology and diagnostics.[68]Major Fields of Practice

Physicians and Surgeons

Physicians are licensed medical professionals who diagnose, treat, and prevent illnesses and injuries through examination, medical history review, diagnostic testing, medication prescription, and health maintenance counseling.[48] They manage a broad spectrum of conditions, from acute infections to chronic diseases, often coordinating care with other health providers.[69] Primary care physicians, such as those in family medicine or internal medicine, focus on ongoing patient relationships and preventive care, while specialists address targeted organ systems or conditions like cardiology or oncology.[70] Surgeons, a specialized subset of physicians, perform operative procedures to repair injuries, remove diseased tissues, or correct deformities, encompassing preoperative assessment, intraoperative execution, and postoperative management.[71] All surgeons hold medical degrees and complete general medical training before pursuing 3–7 additional years of surgical residency, distinguishing them from non-surgical physicians who emphasize non-invasive interventions.[72] Surgical fields include general surgery, orthopedic surgery for musculoskeletal issues, neurosurgery for brain and spine disorders, and cardiothoracic surgery for heart and lung operations, each requiring precision to minimize risks like infection or hemorrhage.[73] In practice, physicians and surgeons collaborate in multidisciplinary teams, with physicians often referring patients for surgical intervention when conservative treatments fail.[74] Globally, physician density stands at approximately 17.2 per 10,000 population as of 2022, with shortages projected in many regions due to aging demographics and expanding healthcare demands.[75] In the United States, over 1.08 million physicians were licensed as of 2025, comprising 77% U.S. medical graduates, though workforce gaps persist in rural areas and certain specialties.[76] Evidence from peer-reviewed analyses underscores that effective physician-surgeon integration improves outcomes, as measured by reduced readmission rates and enhanced patient recovery metrics.[77]Nursing and Advanced Practice Providers

Registered nurses (RNs) constitute the largest segment of the U.S. healthcare workforce, numbering approximately 4.7 million active professionals as of recent estimates, with responsibilities encompassing patient assessment, care coordination, treatment administration, and health education.[78] They develop and implement individualized care plans, monitor patient conditions, and collaborate with interdisciplinary teams in settings ranging from hospitals to community clinics.[14] Entry into the profession requires completion of an associate degree in nursing (ADN), bachelor of science in nursing (BSN), or approved nursing diploma program, followed by passing the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN).[14] [79] Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), including nurse practitioners (NPs), certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), and clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), hold master's or doctoral degrees with specialized clinical training beyond RN licensure.[54] [80] APRNs perform expanded roles such as diagnosing illnesses, ordering and interpreting diagnostic tests, prescribing medications, and managing patient care independently or collaboratively, often in primary or specialty settings.[81] [80] Scope of practice varies by state: full practice authority in 27 states and D.C. allows independent operation, while restricted models in others mandate physician oversight.[82] Workforce projections indicate steady growth for RNs at 5% from 2024 to 2034, yielding about 189,100 annual openings driven by retirements and healthcare demand, though shortages persist due to aging demographics and burnout.[14] APRNs face even stronger demand, with employment projected to expand 40% over the same period, reflecting expanded roles in addressing primary care gaps.[81] The profession remains predominantly female (88%) and aging, with a median RN age of 46 years.[83] [78] Comparative outcome studies yield mixed results on APRN efficacy relative to physicians. Systematic reviews in primary care settings often report equivalent or improved patient satisfaction and preventive counseling with NPs, alongside similar utilization and costs.[84] [85] However, analyses in higher-acuity environments, such as emergency departments, reveal NPs associated with increased resource use, higher hospitalization rates for complex cases, and elevated costs without commensurate outcome improvements compared to physicians.[86] [87] These disparities intensify with patient complexity, suggesting limitations in independent APRN management of severe conditions despite advocacy for broadened autonomy.[86]Allied Health and Diagnostic Professions

Allied health professions encompass a broad array of healthcare roles that deliver diagnostic, therapeutic, preventive, and rehabilitative services, distinct from physicians, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists. These professionals assist in patient care by performing technical procedures, conducting assessments, and providing direct treatment under supervision or independently, depending on scope of practice. The Association of Schools Advancing Health Professions defines allied health to include fields such as dental hygienists, diagnostic medical sonographers, dietitians, medical technologists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, radiographers, respiratory therapists, and speech-language pathologists.[88] In the United States, allied health workers constitute a significant portion of the healthcare workforce, with the Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting over 1.9 million annual job openings projected through 2033 across related occupations due to growth and replacements.[19] Diagnostic professions within allied health specialize in generating clinical data for disease identification and monitoring, often using advanced equipment. Clinical laboratory technologists and technicians analyze blood, urine, and tissue samples to detect abnormalities, performing tests that inform 70-80% of medical decisions in some estimates.[19] Diagnostic medical sonographers operate ultrasound devices to produce images of internal organs, aiding in prenatal, cardiac, and vascular assessments; employment in this role is projected to grow 14% from 2022 to 2032, driven by an aging population and diagnostic technology adoption.[89] Radiologic technologists use X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs for imaging, with similar demand fueled by chronic disease prevalence.[19] Therapeutic allied health roles emphasize rehabilitation and functional improvement. Physical therapists evaluate and treat mobility impairments through exercises and modalities, while occupational therapists focus on daily living skills for patients with injuries or disabilities. Respiratory therapists manage airway and breathing issues, including ventilator support in critical care. The Health Resources and Services Administration projects shortages by 2037 in key areas, such as 6,480 respiratory therapists and substantial gaps in other allied fields, underscoring workforce strain amid rising healthcare needs.[90] Certifications from bodies like the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonography ensure competency, with many roles requiring associate degrees and clinical training.[91]Dentistry and Oral Health

Dentists serve as the primary health professionals responsible for diagnosing, preventing, and treating conditions affecting the teeth, gums, jaws, and associated structures. They perform procedures ranging from routine cleanings and fillings to complex surgeries such as implants and extractions, while also addressing aesthetic concerns through restorative work. In the United States, licensure requires completion of a bachelor's degree, four years of accredited dental school culminating in a Doctor of Dental Surgery (DDS) or Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD) degree, passage of national board examinations, and state-specific clinical assessments.[92][93] The dentist workforce in the US comprised approximately 202,304 active practitioners as of the latest 2023 data, yielding a ratio of 60.4 dentists per 100,000 population. Employment is projected to grow by 4 percent from 2024 to 2034, generating about 4,500 annual openings, driven by retirements and population growth rather than expansion in demand. General dentists constitute the majority, with specialists comprising roughly 15-20 percent; recognized specialties by the American Dental Association include endodontics (root canal therapy), orthodontics (alignment and bite correction), periodontics (gum disease management), prosthodontics (restorations and replacements), oral and maxillofacial surgery (jaw and facial procedures), pediatric dentistry, dental public health, oral pathology, oral and maxillofacial radiology, oral medicine, dental anesthesiology, and orofacial pain. Specialization requires 2-6 additional years of residency training post-dental school.[94][95][15][96] Dental hygienists function as allied oral health professionals focused on preventive care, including patient education, scaling and polishing teeth, applying sealants and fluorides, and screening for diseases like gingivitis and periodontitis. Their scope of practice, defined by state dental practice acts, typically involves direct access to patients under varying supervision levels—ranging from general oversight to collaborative agreements or independent practice in some jurisdictions—and excludes invasive procedures like extractions. Training entails an associate or bachelor's degree from an accredited program, encompassing didactic and clinical coursework, followed by national and state licensure exams. As of 2025, the US employed about 214,100 dental hygienists, supporting broader access to routine oral care amid dentist shortages in underserved areas.[97][98][99][100] Other supporting roles include dental assistants, who aid in chairside procedures, sterilization, and administrative tasks after completing accredited programs or on-the-job training, and dental laboratory technicians, who fabricate prosthetics like crowns and dentures. Oral health professionals collectively address systemic links between oral disease and conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, emphasizing evidence-based interventions like fluoride use and periodontal therapy to mitigate tooth decay and gum inflammation, which affect over 40 percent of US adults.[101][102]Pharmacy and Therapeutics

Pharmacists function as medication experts within health care teams, focusing on the safe and effective use of therapeutics to treat diseases and manage chronic conditions. They evaluate prescriptions for therapeutic appropriateness, potential interactions, dosing accuracy, and patient-specific factors such as renal function or comorbidities, thereby preventing adverse drug events that affect up to 10% of hospitalized patients annually.[103] In therapeutics, pharmacists optimize pharmacotherapy by recommending adjustments, such as switching agents for better efficacy or cost-effectiveness, based on evidence from clinical guidelines and patient data.[104] This role extends beyond dispensing to direct patient care, including counseling on administration, side effects, and lifestyle modifications to enhance adherence, which studies link to a 20-30% reduction in hospitalization rates for conditions like diabetes and hypertension.[105] Clinical pharmacy practice emphasizes collaborative drug therapy management, where pharmacists partner with physicians to monitor outcomes and refine regimens, particularly for polypharmacy in elderly patients averaging 5-10 concurrent medications.[106] In hospital settings, they participate in rounds, antimicrobial stewardship to combat resistance—reducing inappropriate antibiotic use by 20-50% in targeted programs—and transitions of care to minimize readmissions.[107] Community pharmacists contribute through immunizations, health screenings for conditions like osteoporosis or cardiovascular risk, and over-the-counter recommendations, addressing gaps in primary care access.[108] Evidence from systematic reviews indicates these interventions yield net cost savings of $2-5 per dollar invested by averting complications like falls or exacerbations.[109] Emerging therapeutics, including biologics and gene therapies costing millions per dose, demand specialized pharmacy oversight for storage, infusion protocols, and eligibility screening to ensure equitable access and safety.[110] Pharmacists in these areas apply pharmacogenomics to personalize dosing, reducing toxicity risks by tailoring to genetic variants affecting metabolism, as seen in warfarin or oncology regimens.[111] Practice models are shifting toward integrated care, with pharmacists gaining authority in 48 U.S. states for collaborative practice agreements allowing independent prescribing adjustments, enhancing responsiveness to therapeutic needs without physician bottlenecks.[112] Despite these advances, barriers like reimbursement limitations persist, though data affirm pharmacists' role in lowering overall health expenditures through error prevention and outcome optimization.[113]Occupational Hazards

Biological and Infectious Risks