Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

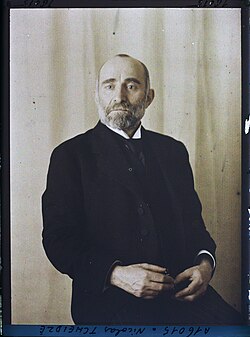

Nikolay Chkheidze

View on WikipediaNikoloz Chkheidze[c] (21 March [O.S. 9] 1864 – 13 June 1926), commonly known as Karlo Chkheidze, was a Georgian politician and statesman. In the 1890s, he promoted the Social Democratic movement in Georgia, and later became a leading Social Democrat in the Russian Empire. He was a key figure in the February Revolution as the Menshevik president of the Executive Committee of Petrograd Soviet. He later served as president of the Transcaucasian Sejm in from February to May 1918, and as parliamentary president of the Democratic Republic of Georgia from 1918 to 1921.[1]

Key Information

Early life and family

[edit]Chkheidze was born into the House of Chkheidze, an aristocratic family in Puti, Kutais Governorate (in the present-day Zestaponi Municipality of the Imereti province of Georgia). From his marriage with Alexandra Taganova (X-1943), he would have four children including a daughter who would accompany him in exile.[2]

Political career

[edit]In 1892 Chkheidze, together with Egnate Ninoshvili, Silibistro Jibladze, Noe Zhordania and Kalenike Chkheidze (his brother), became a founder of the first Georgian Social-Democratic group, Mesame Dasi (the third team).

Russia

[edit]From 1907 to 1917 Chkheidze was a member of the Russian State Duma representing the Tiflis Governorate and gained popularity as a spokesman for the Menshevik faction within the Russian Social Democratic Party. He was an active member of the irregular freemasonic lodge, the Grand Orient of Russia’s Peoples.[3] In 1917 the year of the Russian Revolution, Chkheidze became Chairman of the Petrograd Soviet. He failed to prevent the rise of Bolshevism and refused a post in the Russian Provisional Government. However, he did support its policies and advocated revolutionary oboronchestvo (defencism). He also voted to continue the war against the German Empire.[4][5]

Transcaucasia

[edit]In October 1917 the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia. At the time, Chkheidze was in Georgia. He remained in Georgia and on 23 February 1918, became leader of the Transcaucasian Federation in Tiflis. Some months later the federation was dissolved.[6]

Democratic Republic of Georgia

[edit]

On 26 May 1918 the Act of Independence of Georgia was adopted, Chkheidze was elected chairman of the National Council of Georgia: this Georgian Provisional Assembly decided to appoint a government, to prepare elections and to create a constitutional commission. In February 1919 he was elected a member of the Constituent Assembly of Georgia and on 12 March president of this assembly, but could not participate in its first session because he was located in Paris. Chairing the Georgian delegation to the Versailles Conference, he tried to gain the Entente's support for the Democratic Republic of Georgia. He also proposed to Georges Clemenceau and to David Lloyd George a French or British protectorate for Georgian foreign affairs and defense, but was unsuccessful.[7] Chkheidze, who had 14 years of parliamentary life experience, oversaw the writing of the Constitution by Razhden Arsenidze and 14 other MPs of the majority and the opposition.

France

[edit]In March 1921 when the Red Army invaded Georgia, Chkheidze fled with his family to France via Constantinople.[8] In 1923 and 1924, as part of the Social Democratic Labour Party of Georgia in exile, Chkheidze opposed a national uprising in Georgia. Chkheidze, Irakli Tsereteli, Datiko Sharashidze, and Kale Kavtaradze formed a group called Oppozitsia. In their mind, the Red Army and Cheka were too strong, and the unarmed Georgian people too weak. After the August Uprising of 1924, 10,000 Georgians were executed, and between 50,000 and 100,000 Georgians were deported to Siberia or to Central Asia.

Death

[edit]

On 13 June 1926 Chkheidze committed suicide at his official residence in Leuville-sur-Orge, France. He was buried in Paris, in the Père Lachaise Cemetery.[9]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Lev Kamenev as Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets.

- ^ The Constituent Assembly was declared dissolved by the Bolshevik-Left SR Soviet government, rendering the end the term served.

- ^ Georgian: ნიკოლოზ (კარლო) ჩხეიძე; Russian: Николай (Карло) Семёнович Чхеидзе, romanized: Nikolay (Karlo) Semyonovich Chkheidze)

References

[edit]- ^ "Nikolay Semyonovich Chkheidze". Encyclopedia Britannica. 9 June 2024..

- ^ "Russie, Géorgie et France : Véronique Chéidzé (1909-1986), fille du 1er président de Parlement géorgien". Colisée (in French). 29 November 2013..

- ^ Hass, Ludwik (1983). "The Russian Masonic Movement in the Years 1906 - 1918" (PDF). Acta Poloniae Historica (48): 95–131. ISSN 0001-6829. Retrieved 25 October 2017..

- ^ "Nicolas Chkheidze". Project 1917..

- ^ "Russian Revolution (1917). The Georgian deputy Nicholas Cheidze, executive president of the workers deputies and soldier". Alamy..

- ^ "Géorgie, Russie et France : Nicolas Chéidzé (1864-1926), homme d'État russe et géorgien". Colisée (in French). 9 January 2014..

- ^ "Hidden Story of the Georgian Hero". Georgia Today. 12 March 2019. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019..

- ^ "1ère République en exil". Colisée (in French)..

- ^ "Membres du gouvernement et chefs de file de l'opposition aux obsèques de Nicolas Tcheidze". Samchoblo (in French). Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2019-03-20..

Bibliography

[edit]- Figes, Orlando (1996), A People's Tragedy: A History of the Russian Revolution, New York City: Viking, ISBN 978-0-14-024364-2

- Jones, Stephen F. (2005), Socialism in Georgian Colors: The European Road to Social Democracy 1883–1917, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-67-401902-7

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1951), The Struggle for Transcaucasia (1917–1921), New York City: Philosophical Library, ISBN 978-0-95-600040-8

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Rabinowitch, Alexander (1968), Prelude to Revolution: The Petrograd Bolsheviks and the July 1917 Uprising, Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-25-320661-9

- Rabinowitch, Alexander (1976), The Bolsheviks Come to Power: The Revolution of 1917 in Petrograd, New York City: W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-7453-2269-7

- Rabinowitch, Alexander (2007), The Bolsheviks in Power: The First Year of Soviet Rule in Petrograd, Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-25-334943-9

- Rayfield, Donald (2012), Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia, London: Reaktion Books, ISBN 978-1-78-023030-6

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation (Second ed.), Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-25-320915-3

External links

[edit]- (in Russian) Чхеидзе, Николай Семенович Hronos.km.ru.