Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Abkhazia

View on Wikipedia

Abkhazia,[a][b] officially the Republic of Abkhazia,[c] is a partially recognised state in the South Caucasus, on the eastern coast of the Black Sea, at the intersection of Eastern Europe and West Asia. It covers 8,665 square kilometres (3,346 sq mi) and has a population of around 245,000. Its capital and largest city is Sukhumi.

Key Information

The political status of Abkhazia is a central issue of the Abkhazia conflict and Georgia–Russia relations. Abkhazia is recognised as an independent state only by five states: Russia, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Nauru, and Syria; Georgia and other countries consider Abkhazia as Georgia's sovereign territory. Lacking effective control over the Abkhazian territory, Georgia maintains an Abkhaz government-in-exile.

The region had autonomy within Soviet Georgia at the time when the Soviet Union began to disintegrate in the late 1980s. Simmering ethnic tensions between the Abkhaz—the region's titular ethnicity—and Georgians—the largest single ethnic group at that time—culminated in the 1992–1993 War in Abkhazia, which resulted in Georgia's loss of control over most of Abkhazia and the ethnic cleansing of Georgians from Abkhazia. Despite a 1994 ceasefire agreement and years of negotiations, the dispute remains unresolved. The long-term presence of a United Nations Observer Mission and a Russian-led Commonwealth of Independent States peacekeeping force failed to prevent the flare-up of violence on several occasions. In August 2008, Abkhaz and Russian forces fought a war against Georgian forces, which led to the formal recognition of Abkhazia by Russia, the annulment of the 1994 ceasefire agreement and the termination of the UN mission. On 23 October 2008, the Parliament of Georgia declared Abkhazia a Russian-occupied territory.[9]

Etymology

[edit]The Russian name Абхазия (Abkhaziya) is adapted from the Georgian აფხაზეთი (Apkhazeti). Abkhazia's name in English (/æbˈkɑːziə/ ⓘ;[8] ab-KAH-zee-ə or /æbˈkeɪziə/ ⓘ ab-KAY-zee-ə).[10]

The Abkhaz name Apsny (Abkhaz: Аԥсны, IPA [apʰsˈnɨ]) is etymologised as 'a land of the soul';[11] however, the literal meaning is 'a country of mortals'.[12] It possibly first appeared in the seventh century in an Armenian text, perhaps referring to the ancient Apsilians.[13]

In early Muslim sources, the term Abkhazia was generally used to mean the territory of Georgia.[14][15]

Presumably considered as a successor state of Lazica (Egrisi in Georgian sources), this new polity continued to be referred to as Egrisi in some Byzantine era Georgian and Armenian chronicles (e.g. The Vitae of the Georgian Kings by Leonti Mroveli and The History of Armenia by Hovhannes Draskhanakerttsi).[16]

The Constitution of Abkhazia says the names of the "Republic of Abkhazia" and "Apsny" are equivalent and interchangeable.[17][18]

Before the 20th century, the region was sometimes referred to in English language sources as Abhasia.[19][20]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]Between the 9th and 6th centuries BC, the territory of modern Abkhazia was part of the ancient Kingdom of Colchis.[21][22] Around the 6th century BC, the Greeks established trade colonies along the Black Sea coast of present-day Abkhazia, in particular at Pitiunt and Dioscurias.[23]

Classical authors described various peoples living in the region and the great multitude of languages they spoke.[24] Arrian, Pliny and Strabo have given accounts of the Abasgoi[25] and Moschoi[26] peoples somewhere in modern Abkhazia on the eastern shore of the Black Sea. This region was subsequently absorbed in 63 BC into the Kingdom of Lazica.[27][28]

According to an Eastern tradition, Simon the Zealot died in Abkhazia during a missionary trip and was buried in Nicopsis; his mortal remains were later transferred to Anacopia.[29]

Within the Roman & Byzantine Empires

[edit]The Roman Empire conquered Lazica in the 1st century AD; however, the Roman presence was confined to port cities.[30] According to Arrian, the Abasgoi and Apsilae peoples were nominal Roman subjects, and there was a small Roman outpost in Dioscurias.[31] Abasgoi likely served in the Roman army in Ala Prima Abasgorum, which was stationed in Egypt.[32] After the 4th century Lazica regained a measure of independence, but remained within the Byzantine Empire's sphere of influence.[33] Anacopia was the principality's capital. The country was mostly Christian, with the archbishop's seat in Pityus.[34] Stratophilus, the Metropolitan of Pityus, participated in the First Council of Nicaea in 325.[35]

Around the middle of the 6th century AD, the Byzantines and the neighbouring Sassanid Persia fought for supremacy over Abkhazia, a conflict known as the Lazic War. During the war the Abasgians revolted against the Byzantine Empire and requested Sasanian assistance; the revolt was suppressed by General Bessas.[36][37][36]

An Arab incursion into Abasgia, led by Marwan II, was repelled by Prince Leon I jointly with his Lazic and Iberian allies in 736. Leon I then married Mirian's daughter and a successor, King Leon II exploited this dynastic union to acquire Lazica in the 770s.[38]

The successful defence against the Arab Caliphate, and new territorial gains in the east gave the Abasgian princes enough power to claim more autonomy from the Byzantine Empire. Circa 778, Prince Leon II, with the help of the Khazars, declared independence from the Byzantine Empire and transferred his residence to Kutaisi. During this period the Georgian language replaced Greek as the language of literacy and culture.[39]

Within the Kingdom of Georgia

[edit]The Kingdom of Abkhazia flourished between 850 and 950 AD, which ended by unification of Abkhazia and eastern Georgian states under a single Georgian monarchy ruled by King Bagrat III at the end of the 10th century and the beginning of the 11th century.[40]

During the reign of Queen Tamar, Georgian chronicles mention Otagho as the Eristavi of Abkhazia.[41] He was one of the first representatives of the House of Shervashidze (also known as Chachba) which went on to rule Abkhazia until the 19th century.[42]

In the 1240s, Mongols divided Georgia into eight military-administrative sectors (tümens). The territory of contemporary Abkhazia formed part of the tümen administered by Tsotne Dadiani.[43]

Ottoman Influence

[edit]In the 16th century, after the break-up of the Georgian Kingdom into small kingdoms and principalities, the Principality of Abkhazia (nominally a vassal of the Kingdom of Imereti) emerged, ruled by the Shervashidze dynasty.[3] In 1453, the Ottomans first attacked Sukhumi, and in the 1570s, they had a garrison there. Throughout the 17th century, they continued to launch attacks, leading to the imposition of tribute on Abkhazia.

Ottoman influence grew significantly in the 18th century with the construction of a fort in Sukhumi, accompanied by a conversion of the rulers of Abkhazia and many other Abkhaz to Islam. Nonetheless, conflicts between the Abkhaz and Turks persisted.[44] The spread of Islam in Abkhazia was first evidenced by the Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi in 1641. Despite this, the Islamisation was more evident in the higher levels of society rather than the general population.[45][46] In his work, Çelebi also wrote that the principal tribe of Abkhazian principality, Chách, spoke Mingrelian language, a subset of Kartvelian (Georgian) languages.[47][48]

Abkhazia sought protection from the Russian Empire in 1801 but was declared "an autonomous principality" by the Russians in 1810.[49][50] Russia then annexed Abkhazia in 1864, and Abkhaz resistance was quashed as the Russians deported Muslim Abkhaz to Ottoman territories.[3][51][49]

Within Russia

[edit]

In the beginning of the 19th century, while the Russians and Ottomans were vying for control of the region, the rulers of Abkhazia shifted back and forth across the religious divide.[52] The first attempt to enter into relations with Russia was made by Prince Kelesh-Bey in 1803, shortly after the incorporation of eastern Georgia into the expanding Tsarist empire in 1801. However, pro-Ottoman sympathy in Abkhazia prevailed for a short time after Kelesh-Bey was assassinated by his son, Aslan-Bey, in 1801.[53] On 2 July 1810, Russian Marines stormed Sukhum-Kale and had Aslan-Bey replaced with his rival and brother, Sefer Ali-Bey, who had converted to Christianity and assumed the name of George. Abkhazia joined the Russian Empire as an autonomous principality, in 1810.[3] However, Sefer-bey's rule was limited and many mountain regions were as independent as before. Sefer-bey ruled from 1810 to 1821.[54] The next Russo-Turkish war (1828–1829) strongly enhanced the Russian positions, leading to a further split in the Abkhaz elite, mainly along religious divisions. During the Crimean War (1853–1856), Russian forces had to evacuate Abkhazia and Prince Hamud-Bey Sharvashidze-Chachba (Mikhail), who ruled from 1822 to 1864, seemingly switched to the Ottomans.[55]

Later on, the Russian presence strengthened and the highlanders of Western Caucasia were finally subjugated by Russia in 1864. The autonomy of Abkhazia, which had functioned as a pro-Russian "buffer zone" in this troublesome region, was no longer needed by the Tsarist government and the rule of the Sharvashidze came to an end; in November 1864, Prince Mikhail (Hamud-Bey) was forced to renounce his rights and resettle in Voronezh, Russia.[56] Later that same year, Abkhazia was incorporated into the Russian Empire as a special military province of Sukhum-Kale which was transformed, in 1883, into an okrug as part of the Kutaisi Governorate. Large numbers of Muslim Abkhazians, said to have constituted as much as 40% of the Abkhazian population, emigrated to the Ottoman Empire between 1864 and 1878 together with other Muslim populations of the Caucasus, a process known as Muhajirism.[3]

Large areas of the region were left uninhabited and many Armenians, Georgians, Russians and others subsequently migrated to Abkhazia, resettling much of the vacated territory.[57] Some Georgian historians assert that Georgian tribes (Svans and Mingrelians) had populated Abkhazia since the time of the Colchis kingdom.[58] By official decision of the Russian authorities, the residents of Abkhazia and Samurzakano had to study and pray in Russian. After the mass deportation of 1878, Abkhazians were left in the minority, officially branded "guilty people", and had no leader capable of mounting serious opposition to Russification.[59]

On 17 March 1898, the synodal department of the Russian Orthodox Church of Georgia-Imereti, by Order 2771, again prohibited teaching and the conduct of religious services in Georgian. Mass protests by the Georgian population of Abkhazia and Samurzakano followed, news of which reached the Russian emperor. On 3 September 1898 the Holy Synod issued Order 4880, which decreed that those parishes where the congregation was Mingrelian (i.e. Georgian), conduct both church services and church education in Georgian, while Abkhazian parishes use old Slavic. In the Sukhumi district, this order was carried out in only three of 42 parishes.[59] Tedo Sakhokia demanded the Russian authorities introduce Abkhazian and Georgian languages in church services and education. The official response was a criminal case brought against Tedo Sakhokia and leaders of his "Georgian Party" active in Abkhazia.[59]

Within the Georgian Democratic Republic

[edit]Following the October Revolution in Russia, the Transcaucasian Commissariat was set up in Southern Caucasus, which gradually took steps towards the independence.[60] Transcaucasia declared its independence from Russia on 9 April 1918 as a federative republic. On 8 May 1918, the Bolsheviks seized power in Abkhazia and disbanded the local Abkhaz People's Council. It requested aid from the Transcausian authorities, which dispatched the Georgian People's Guard and defeated the rebels on 17 May.[61]

On 26 May 1918, Georgia declared independence from the Transcaucasian Federation, which dissolved on 28 May. On 8 June 1918, the Abkhaz People's Council signed a treaty with the Georgian National Council, which confirmed Abkhazia's status as an autonomy within the Georgian Democratic Republic. The Georgian army defeated another Bolshevik rebellion in the region. It remained part of Georgia after another Bolshevik revolt and a Turkish expedition were defeated in 1918.[citation needed] The Russian general and a leader of White movement Anton Denikin laid claims on Abkhazia and captured Gagra, but the Georgians counter-attacked in April 1919 and retook the city.[62][63] Denikin's Volunteer Army was eventually defeated by the Red Army, and Bolshevik Russia signed an agreement with Georgia in May 1920, recognising Abkhazia as a part of Georgia.[62]

In 1919, a first election was held to the Abkhaz People's Council. The Council favoured being an autonomous region within Georgia, and it lasted until the Red Army invasion of Georgia in February 1921.[64] On 20 March 1919, the newly elected Abkhazian People's Council adopted the "Act on Abkhazian Autonomy", which formalised the establishment of the Abkhazian Autonomy within the Georgian Democratic Republic.[65]

Within the Soviet Union

[edit]

In 1921, the Bolshevik Red Army invaded Georgia and ended its short-lived independence. Abkhazia was made a socialist Soviet republic (SSR Abkhazia) with the ambiguous status of a "treaty republic" associated with the Georgian SSR.[3][66][67] Under the korenizatsiia policy of the Soviet Union, the Abkhaz people were not considered as the "advanced" people, and thus saw an increased focus on their national language and cultural development.[68] Under this policy, the Abkhaz received various benefits such as schooling in their language; the official literary language was established for the first time. Between 1922 and 1926 the share of Abkhaz increased from 19.8% to 27.8% of the population (possibly due to the immigration of ethnic Abkhaz from Turkey or re-identification as Abkhaz). Their share among the members of the local communist party grew from 10% to the 25%. Meanwhile, the proportion of ethnic Georgian population decreased from 42% in 1922 to 36% in 1926, while their proportion in the local communist party also decreased from 40% to 33%.[69] In 1931, Joseph Stalin made it an autonomous republic (Abkhaz ASSR) within the Georgian SSR.[51] In the Terror of 1937–38, the ruling elite was purged of Abkhaz and by 1952 over 80% of the 228 top party and government officials and enterprise managers were ethnic Georgians; there remained 34 Abkhaz, 7 Russians and 3 Armenians in these positions.[70] Georgian Communist Party leader Kandid Charkviani supported the Georgianization of Abkhazia.[71] Starting from 1939, peasant households from the rest of the Georgian SSR were resettled to Abkhazia which changed its demographic makeup significantly.[72][73][74] The publishing of materials in Abkhazian dwindled and was eventually stopped altogether; Abkhaz schools were closed in 1945–1946, requiring Abkhaz children to study in the Georgian language.[75][76][77][78] This was part of the change in the general Soviet and Stalinist policy of national consolidation carried out in all Soviet republics to assimilate the ethnic minorities into titular nationalities, which would in the end be assimilated into the "Soviet people" under the lead of "elder brother" Russians in the "pyramid of assimilation".[79] The teaching of Abkhaz language was preserved in the new reorganised Abkhaz schools as a mandatory subject by the decision of the Georgian Communist Party.[80][better source needed]

The policy of repression was eased after Stalin's death and Beria's execution, and the Abkhaz were given a greater role in the governance of the republic.[51] As in most of the smaller autonomous republics, the Soviet government encouraged the development of culture and particularly of literature.[81] The Abkhazian ASSR was the only autonomous republic in the USSR in which the language of the titular nation (in that case Abkhazian) was confirmed in its constitution as one of its official languages.[82]

In the post-war period, the Abkhazian ASSR was dominated by the ethnic Abkhazs, who occupied many more positions in the autonomous republic compared to Georgians. During the late Soviet period, ethnic Abkhazs occupied 41% of the seats in Abkhazian Supreme Soviet, and 67% of the republican ministers were ethnically Abkhaz. Moreover, they held even larger proportion of lower level official posts within the autonomous republic. The first secretary of the communist party in Abkhazia was also ethnically Abkhaz. All of this was despite the fact that Abkhazians made up only 17.8% of the region's population, while Georgians were 45.7% and other ethnicities (Greeks, Russians, Armenians, etc.) — 36.5%.[83]

Post-Soviet Georgia

[edit]As the Soviet Union began to disintegrate at the end of the 1980s, ethnic tensions grew between the Abkhaz and Georgians over Georgia's moves towards independence. Many Abkhaz opposed this, fearing that an independent Georgia would lead to the elimination of their autonomy, and argued instead for the establishment of Abkhazia as a separate Soviet republic in its own right. With the onset of perestroika, the agenda of Abkhaz nationalists became more radical and exclusive.[84] In 1988, they began to ask for the reinstatement of Abkhazia's former status of Union Republic, as the submission of Abkhazia to another Union Republic was not considered to give enough guarantees of their development.[84] They justified their request by referring to the Leninist tradition of the right of nations to self-determination, which they asserted was violated when Abkhazia's sovereignty was curtailed in 1931.[84] In June 1988, a manifesto defending Abkhaz distinctiveness (known as the Abkhazian Letter) was sent to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.[85] The Georgian–Abkhaz dispute turned violent on 16 July 1989 in Sukhumi. Numerous Georgians were killed or injured when they tried to enroll in a Georgian university instead of an Abkhaz one. After several days of violence, Soviet troops restored order in the city.[86]

In March 1990, Georgia declared sovereignty, unilaterally nullifying treaties concluded by the Soviet government since 1921 and thereby moving closer to independence. The Republic of Georgia boycotted the 17 March 1991 all-Union referendum on the renewal of the Soviet Union called by Gorbachev; however, 52.3% of Abkhazia's population (almost all of the ethnic non-Georgian population) took part in the referendum and voted by an overwhelming majority (98.6%) to preserve the Union.[87][88] Most ethnic non-Georgians in Abkhazia later boycotted a 31 March referendum on Georgia's independence, which was supported by a huge majority of Georgia's population. Within weeks, Georgia declared independence on 9 April 1991, under former Soviet dissident Zviad Gamsakhurdia. Under Gamsakhurdia, the situation was relatively calm in Abkhazia and a power-sharing agreement was soon reached between the Abkhaz and Georgian factions, granting to the Abkhaz a certain over-representation in the local legislature.[89][90]

Gamsakhurdia's rule was soon challenged by armed opposition groups, under the command of Tengiz Kitovani, that forced him to flee the country in a military coup in January 1992. Gamsakhurdia was replaced by former Soviet Georgian leader and Soviet foreign minister Eduard Shevardnadze, who became the country's head of state.[91] On 21 February 1992, Georgia's ruling military council announced that it was abolishing the Soviet-era constitution and restoring the 1921 Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia. Many Abkhaz interpreted this as an abolition of their autonomous status, although the 1921 constitution contained a provision for the region's autonomy.[92] On 23 July 1992, the Abkhaz faction in the republic's Supreme Council declared effective independence from Georgia, although the session was boycotted by ethnic Georgian deputies and the gesture went unrecognised by any other country. The Abkhaz leadership launched a campaign of ousting Georgian officials from their offices, a process which was accompanied by violence. In the meantime, the Abkhaz leader Vladislav Ardzinba intensified his ties with hardline Russian politicians and military elite and declared he was ready for a war with Georgia.[93] To respond to this situation, Eduard Shevardnadze, new leader of Georgia, had interrupted his trip to Western Georgia, where the Georgian Civil War had been going on between his government and supporters of former President Zviad Gamsakhurdia, ousted during the December 1991 Coup. Shevardnadze announced that the Abkhaz faction took the decision without considering the opinion of the majority of population in Abkhazia.[94]

War in Abkhazia

[edit]

In August 1992, war broke out when the National Guard of Georgia entered Abkhazia to free captive Georgian officials,[95][96][97] and to reopen the railway line.[98][99][100][96][101][102][103] Abkhaz troops were the first to open fire.[95][100] Abkhaz separatist government retreated to Gudauta where the Russian military base was located.[95][96][97][104] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported the ethnic-based violence against Georgians in Gudauta.[105] The Abkhaz were relatively unarmed at the time and the Georgian troops were able to march into the capital Sukhumi with relatively little resistance[106] and subsequently engaged in ethnically based pillage, looting, assault, and murder.[107]

The Abkhaz military defeat was met with a hostile response by the self-styled Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus, an umbrella group uniting a number of movements in the North Caucasus, including elements of Circassians, Abazins, Chechens, Cossacks, Ossetians and hundreds of volunteer paramilitaries and mercenaries from Russia, including the then-little-known Shamil Basayev, later a leader of the anti-Moscow Chechen secessionists. They sided with the Abkhaz separatists to fight against the Georgian government. Russian military did not impede the crossing of the Russia-Georgia border by the North Caucasian militants into Abkhazia.[108][97][109][95] In the case of Basayev, it has been suggested that when he and the members of his battalion came to Abkhazia, they received training by the Russian Army (though others dispute this), presenting another possible motive.[110] On September 25, 1992, Russian Supreme Council (parliament) passed a resolution which condemned Georgia, supported Abkhazia and called for the suspension of the delivery of any weapons and equipment to Georgia and the deployment of a Russian peacekeeping force in Abkhazia. It was sponsored by a Russian nationalist politician Sergei Baburin, a Russian deputy who met Vladislav Ardzinba and argued that he was not that much sure that Abkhazia was part of Georgia.[111] In October, the Abkhaz and North Caucasian paramilitaries mounted a major offensive against Gagra after breaking a cease-fire, which drove the Georgian forces out of large swathes of the republic. Shevardnadze's government accused Russia of giving covert military support to the rebels with the aim of "detaching from Georgia its native territory and the Georgia-Russian frontier land". 1992 ended with the rebels in control of much of Abkhazia northwest of Sukhumi.[citation needed]

The conflict was in stalemate until July 1993, when Abkhaz separatist militias launched an abortive attack on Georgian-held Sukhumi. They surrounded and heavily shelled the capital, where Shevardnadze was trapped. The warring sides agreed to a Russian-brokered truce in Sochi at the end of July. But the ceasefire broke down again on 16 September 1993. Abkhaz forces, with armed support from outside Abkhazia, launched attacks on Sukhumi and Ochamchire. Notwithstanding UN Security Council's call for the immediate cessation of hostilities and its condemnation of the violation of the ceasefire by the Abkhaz side, fighting continued.[112] After ten days of heavy fighting, Sukhumi was taken by Abkhazian forces on 27 September 1993. Shevardnadze narrowly escaped death, after vowing to stay in the city no matter what. He changed his mind, however, and decided to flee when separatist snipers fired on the hotel where he was staying. Abkhaz, North Caucasian militants, and their allies committed numerous atrocities[113] against the city's remaining ethnic Georgians, in what has been dubbed the Sukhumi Massacre. The mass killings and destruction continued for two weeks, leaving thousands dead and missing.[citation needed]

The Abkhaz forces quickly overran the rest of Abkhazia as the Georgian government faced a second threat; an uprising by the supporters of the deposed Zviad Gamsakhurdia in the region of Mingrelia (Samegrelo). Only a small region of eastern Abkhazia, the upper Kodori gorge, remained under Georgian control (until 2008).[citation needed]

During the war, gross human rights violations were reported on both sides (see Human Rights Watch report).[113] Georgian troops have been accused of having committed looting[106] and murders "for the purpose of terrorising, robbing and driving the Abkhaz population out of their homes"[113] in the first phase of the war (according to Human Rights Watch), while Georgia blames the Abkhaz forces and their allies for the ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia, which has also been recognised by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Summits in Budapest (1994),[114] Lisbon (1996)[115] and Istanbul (1999).[116]

Ethnic cleansing of Georgians

[edit]

Before the 1992 War in Abkhazia, Georgians made up nearly half of Abkhazia's population, while less than one-fifth of the population was Abkhaz.[117] As the war progressed, confronted with hundreds of thousands of ethnic Georgians who were unwilling to leave their homes, the Abkhaz separatists implemented the process of ethnic cleansing in order to expel and eliminate the Georgian ethnic population in Abkhazia.[118][119] About 5,000 were killed, 400 went missing[120] and up to 250,000 ethnic Georgians were expelled from their homes.[121] According to International Crisis Group, as of 2006 slightly over 200,000 Georgians remained displaced in Georgia proper.[122]

The campaign of ethnic cleansing also included Russians, Armenians, Greeks, moderate Abkhaz and other minor ethnic groups living in Abkhazia. More than 20,000 houses owned by ethnic Georgians were destroyed. Hundreds of schools, kindergartens, churches, hospitals, and historical monuments were pillaged and destroyed.[123][better source needed] Following the process of ethnic cleansing and mass expulsion, the population of Abkhazia has been reduced to 216,000, from 525,000 in 1989.[124] Pogroms against ethnic Georgians organised by Abkhaz leaders continued even after the end of war, as far as February 1995.[125]

Of about 250,000 Georgian refugees, some 60,000 subsequently returned to Abkhazia's Gali District between 1994 and 1998, but tens of thousands were displaced again when fighting resumed in the Gali District in 1998. Nevertheless, between 40,000 and 60,000 refugees have returned to the Gali District since 1998, including persons commuting daily across the ceasefire line and those migrating seasonally in accordance with agricultural cycles.[126] The human rights situation remained precarious for a while in the Georgian-populated areas of the Gali District. The United Nations and other international organisations have been fruitlessly urging the Abkhaz de facto authorities "to refrain from adopting measures incompatible with the right to return and with international human rights standards, such as discriminatory legislation... [and] to cooperate in the establishment of a permanent international human rights office in Gali and to admit United Nations civilian police without further delay."[127] Key officials of the Gali District are virtually all ethnic Abkhaz, though their support staff are ethnic Georgian.[128]

Post-war

[edit]

Presidential elections were held in Abkhazia on 3 October 2004. Russia supported Raul Khajimba, the prime minister backed by the ailing outgoing separatist President Vladislav Ardzinba.[129] Posters of Russia's President Vladimir Putin together with Khajimba, who, like Putin, had worked as a KGB official, were everywhere in Sukhumi.[130] Deputies of Russia's parliament and Russian singers, led by Joseph Cobsohn, a State Duma deputy and a popular singer, came to Abkhazia, campaigning for Khajimba.[131]

However, Khajimba lost the elections to Sergei Bagapsh. The tense situation in the republic led to the cancellation of the election results by the Supreme Court. After that, a deal was struck between former rivals to run jointly, with Bagapsh as a presidential candidate and Khajimba as a vice-presidential candidate. They received more than 90% of the votes in the new election.[132]

In July 2006, Georgian forces launched a successful police operation against the rebelled administrator of the Georgian-populated Kodori Valley, Emzar Kvitsiani. Kvitsiani had been appointed by the previous president of Georgia Eduard Shevardnadze and refused to recognise the authority of president Mikheil Saakashvili, who succeeded Shevardnadze after the Rose Revolution. Although Kvitsiani escaped capture by Georgian police, the Kodori Gorge was brought back under the control of the central government in Tbilisi.[133]

Sporadic acts of violence continued throughout the postwar years. Despite the peacekeeping status of the Russian peacekeepers in Abkhazia, Georgian officials routinely claimed that Russian peacekeepers were inciting violence by supplying Abkhaz rebels with arms and financial support. Russian support of Abkhazia became pronounced when the Russian ruble became the de facto currency and Russia began issuing passports to the population of Abkhazia.[134] Georgia has also accused Russia of violating its airspace by sending helicopters to attack Georgian-controlled towns in the Kodori Gorge. In April 2008, a Russian MiG – prohibited from Georgian airspace, including Abkhazia – shot down a Georgian UAV.[135][136]

On 9 August 2008, Abkhazian forces fired on Georgian forces in Kodori Gorge. This coincided with the 2008 South Ossetia war where Russia decided to support the Ossetian separatists who had been attacked by Georgia.[137][138] The conflict escalated into a full-scale war between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Georgia. On 10 August 2008, an estimated 9,000 Russian soldiers entered Abkhazia ostensibly to reinforce the Russian peacekeepers in the republic. About 1,000 Abkhazian soldiers moved to expel the residual Georgian forces within Abkhazia in the Upper Kodori Gorge.[139] By 12 August the Georgian forces and civilians had evacuated the last part of Abkhazia under Georgian government control. Russia recognised the independence of Abkhazia on 26 August 2008.[140] This was followed by the annulment of the 1994 ceasefire agreement and the termination of UN and OSCE monitoring missions.[141] On 28 August 2008, the Parliament of Georgia passed a resolution declaring Abkhazia a Russian-occupied territory.[142][143]

Since independence was recognised by Russia, a series of controversial agreements were made between the Abkhazian government and the Russian Federation that leased or sold a number of key state assets and relinquished control over the borders. In May 2009 several opposition parties and war veteran groups protested against these deals complaining that they undermined state sovereignty and risked exchanging one colonial power (Georgia) for another (Russia).[144] The vice-president, Raul Khajimba, resigned on 28 May saying he agreed with the criticism the opposition had made.[145] Subsequently, a conference of opposition parties nominated Raul Khajimba as their candidate in the December 2009 Abkhazian presidential election won by Sergei Bagapsh.[citation needed]

Political developments since 2014

[edit]In the spring of 2014, the opposition submitted an ultimatum to President Aleksandr Ankvab to dismiss the government and make radical reforms.[146] On 27 May 2014, in the centre of Sukhumi, 10,000 supporters of the Abkhaz opposition gathered for a mass demonstration.[147] On the same day, Ankvab's headquarters in Sukhumi was stormed by opposition groups led by Raul Khajimba, forcing him into flight to Gudauta.[148] The opposition claimed that the protests were sparked by poverty, but the main point of contention was President Ankvab's liberal policy towards ethnic Georgians in the Gali region. The opposition said these policies could endanger Abkhazia's ethnic Abkhazian identity.[146]

After Ankvab fled the capital, on 31 May, the People's Assembly of Abkhazia appointed parliamentary speaker Valery Bganba as acting president, declaring Ankvab unable to serve. It also decided to hold an early presidential election on 24 August 2014. Ankvab soon declared his formal resignation, although he accused his opponents of acting immorally and violating the constitution.[149] Raul Khajimba was later elected president, taking office in September 2014.[150]

In November 2014, Vladimir Putin moved to formalise the Abkhazian military's relationship as part of the Russian armed forces, signing a treaty with Khajimba.[151][152] The Georgian government denounced the agreement as "a step towards annexation".[153]

Khajimba was re-elected with a margin of less than 2% in 2019.[154] In January 2020 the Abkhazian Supreme Court annulled the results, following protests against Khajimba.[155] Khajimba resigned the presidency on 12 January, and new elections were called for 22 March.[156] Aslan Bzhania was elected in the subsequent elections with around 59% of the vote.[157]

In December 2021, there was a unrest.[158] Protests took place in November 2024 after the arrest of five opposition activists who opposed an investment agreement with Russia, which led to the resignation of then President Aslan Bzhania and a new presidential election in February 2025.[159] Acting president Badra Gunba was elected, receiving 56% of the vote.[160] Russia, took an unprecedented role in meddling in the 2025 elections according to analysts.[161]

Status

[edit]

Abkhazia, Transnistria, and South Ossetia are post-Soviet "frozen conflict" zones.[162] These three states maintain friendly relations with each other and form the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations.[163][164][165] Russia and Nicaragua officially recognised Abkhazia after the Russo-Georgian War. Venezuela recognised Abkhazia in September 2009.[166][167] In December 2009, Nauru recognised Abkhazia, reportedly in return for $50 million in humanitarian aid from Russia.[168] The unrecognised republic of Transnistria and the partially recognised republic of South Ossetia have recognised Abkhazia since 2006. Abkhazia is also a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO).[citation needed]

A majority of sovereign states recognise Abkhazia as an integral part of Georgia and support its territorial integrity according to the principles of international law, although Belarus has expressed sympathy toward the recognition of Abkhazia.[169] Some have officially noted Abkhazia as under occupation by the Russian military.[170][171][172] The United Nations has been urging both sides to settle the dispute through diplomatic dialogue and ratifying the final status of Abkhazia in the Georgian constitution.[113][173] However, the Abkhaz de facto government considers Abkhazia a sovereign country even if it is recognised by few other countries. In early 2000, then-UN Special Representative of the Secretary General Dieter Boden and the Group of Friends of Georgia, consisting of the representatives of Russia, the United States, Britain, France, and Germany, drafted and informally presented a document to the parties outlining a possible distribution of competencies between the Abkhaz and Georgian authorities, based on core respect for Georgian territorial integrity. The Abkhaz side, however, has never accepted the paper as a basis for negotiations.[174] Eventually, Russia also withdrew its approval of the document.[175] In 2005 and 2008, the Georgian government offered Abkhazia a high degree of autonomy and possible federal structure within the borders and jurisdiction of Georgia.[citation needed]

On 18 October 2006, the People's Assembly of Abkhazia passed a resolution, calling upon Russia, international organisations and the rest of the international community to recognise Abkhaz independence on the basis that Abkhazia possesses all the properties of an independent state.[176] The United Nations has reaffirmed "the commitment of all Member States to the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Georgia within its internationally recognised borders" and outlined the basic principles of conflict resolution which call for immediate return of all displaced persons and for non-resumption of hostilities.[177]

Georgia accuses the Abkhaz secessionists of having conducted a deliberate campaign of ethnic cleansing of up to 250,000 Georgians, a claim supported by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE; Budapest, Lisbon and Istanbul declaration).[178] The UN Security Council has avoided the use of the term "ethnic cleansing" but has affirmed "the unacceptability of the demographic changes resulting from the conflict".[179] On 15 May 2008, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a non-binding resolution recognising the right of all refugees (including victims of reported "ethnic cleansing") to return to Abkhazia and to retain or regain their property rights there. It "regretted" the attempts to alter pre-war demographic composition and called for the "rapid development of a timetable to ensure the prompt voluntary return of all refugees and internally displaced persons to their homes."[180]

On 28 March 2008, the President of Georgia Mikheil Saakashvili unveiled his government's new proposals to Abkhazia: the broadest possible autonomy within the framework of a Georgian state, a joint free economic zone, representation in the central authorities including the post of vice-president with the right to veto Abkhaz-related decisions.[181] The Abkhaz leader Sergei Bagapsh rejected these new initiatives as "propaganda", leading to Georgia's complaints that this skepticism was "triggered by Russia, rather than by real mood of the Abkhaz people."[182]

On 3 July 2008, the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly passed a resolution at its annual session in Astana, expressing concern over Russia's recent moves in breakaway Abkhazia. The resolution calls on the Russian authorities to refrain from maintaining ties with the breakaway regions "in any manner that would constitute a challenge to the sovereignty of Georgia" and also urges Russia "to abide by OSCE standards and generally accepted international norms with respect to the threat or use of force to resolve conflicts in relations with other participating States."[183]

On 9 July 2012, the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly passed a resolution at its annual session in Monaco, underlining Georgia's territorial integrity and referring to breakaway Abkhazia and South Ossetia as "occupied territories". The resolution "urges the Government and the Parliament of the Russian Federation, as well as the de facto authorities of Abkhazia, Georgia and South Ossetia, Georgia, to allow the European Union Monitoring Mission unimpeded access to the occupied territories." It also says that the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly is "concerned about the humanitarian situation of the displaced persons both in Georgia and in the occupied territories of Abkhazia, Georgia and South Ossetia, Georgia, as well as the denial of the right of return to their places of living." The Assembly is the parliamentary dimension of the OSCE with 320 lawmakers from the organisation's 57 participating states, including Russia.[184]

Law on occupied territories of Georgia

[edit]

In late October 2008, President Saakashvili signed into law legislation on the occupied territories passed by the Georgian Parliament. The law covers the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and Tskhinvali (territories of former South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast).[185][186] The law spells out restrictions on free movement and economic activity in the territories. In particular, according to the law, foreign citizens should enter the two breakaway regions only through Georgia proper. Entry into Abkhazia should be carried out from the Zugdidi Municipality and into South Ossetia from the Gori Municipality. The major road leading to South Ossetia from the rest of Georgia passes through the Gori District.[187]

The legislation, however, also lists "special" cases in which entry into the breakaway regions will not be regarded as illegal. It stipulates that a special permit on entry into the breakaway regions can be issued if the trip there "serves Georgia's state interests; peaceful resolution of the conflict; de-occupation or humanitarian purposes." The law also bans any type of economic activity – entrepreneurial or non-entrepreneurial, if such activities require permits, licences or registration in accordance with Georgian legislation. It also bans air, sea and railway communications and international transit via the regions, mineral exploration and money transfers. The provision covering economic activities is retroactive, going back to 1990.[187]

The law says that the Russian Federation – the state which has carried out military occupation – is fully responsible for the violation of human rights in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The Russian Federation, according to the document, is also responsible for compensation of material and moral damage inflicted on Georgian citizens, stateless persons and foreign citizens, who are in Georgia and enter the occupied territories with appropriate permits. The law also says that de facto state agencies and officials operating in the occupied territories are regarded by Georgia as illegal. The law will remain in force until "the full restoration of Georgian jurisdiction" over the breakaway regions is realised.[187]

Status-neutral passports

[edit]According to a 2006 report, Georgia considers all residents of Abkhazia its citizens, while they see themselves as Abkhaz citizens.[122]

In the summer of 2011, the Parliament of Georgia adopted a package of legislative amendments providing for the issuance of neutral identification and travel documents to residents of Abkhazia and the former South Ossetian autonomous province of Georgia. The document allows travelling abroad as well as enjoying social benefits existing in Georgia. The new neutral identification and travel documents were called "neutral passports".[188] The status-neutral passports do not carry state symbols of Georgia.[189] Abkhazia's foreign minister, Viacheslav Chirikba, criticised the status-neutral passports and called their introduction "unacceptable".[190] Some Abkhazian residents with Russian passports were being denied Schengen visas.[189]

As of May 2013, neutral documents have been recognised by Japan, the Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, the United States, Bulgaria, Poland, Israel, Estonia and Romania.[188]

According to Russian media, the President of the Republic of Abkhazia, Alexander Ankvab threatened international organisations that accepted neutral passports, saying during a meeting with the leadership of the foreign ministry that "international organizations that suggest the so-called neutral passports, will leave Abkhazia."[191]

Russian involvement

[edit]

During the Georgian–Abkhaz conflict, the Russian authorities and military supplied logistical and military aid to the separatist side.[113] Today, Russia still maintains a strong political and military influence over separatist rule in Abkhazia. Russia has also issued passports to the citizens of Abkhazia since 2000 (as Abkhazian passports cannot be used for international travel) and subsequently paid them retirement pensions and other monetary benefits. More than 80% of the Abkhazian population had received Russian passports by 2006. As Russian citizens living abroad, Abkhazians do not pay Russian taxes or serve in the Russian Army.[192][193] About 53,000 Abkhazian passports have been issued as of May 2007.[194]

Moscow, at certain times, hinted that it might recognise Abkhazia and South Ossetia when Western countries recognised the independence of Kosovo, suggesting that they had created a precedent. Following Kosovo's declaration of independence, the Russian parliament released a joint statement reading: "Now that the situation in Kosovo has become an international precedent, Russia should take into account the Kosovo scenario... when considering ongoing territorial conflicts."[195] Initially Russia continued to delay recognition of both of these republics. However, on 16 April 2008, the outgoing Russian president Vladimir Putin instructed his government to establish official ties with South Ossetia and Abkhazia, leading to Georgia's condemnation of what it described as an attempt at "de facto annexation"[196] and criticism from the European Union, NATO, and several Western governments.[197]

Later in April 2008, Russia accused Georgia of trying to exploit NATO support in order to control Abkhazia by force and announced it would increase its military presence in the region, pledging to retaliate militarily against Georgia's efforts. Georgian Prime Minister Lado Gurgenidze said Georgia will treat any additional troops in Abkhazia as "aggressors".[198]

In response to the Russo-Georgian War, the Federal Assembly of Russia called an extraordinary session on 25 August 2008 to discuss recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[199] Following a unanimous resolution passed by both houses of the parliament calling on the Russian president to recognise independence of the breakaway republics,[200] Russian president, Dmitry Medvedev, officially recognised both on 26 August 2008.[201][202] Russian recognition[203] was condemned by NATO nations, OSCE and European Council nations[204][205][206][207][208] due to "violation of territorial integrity and international law".[207][209] UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon stated that sovereign states have to decide themselves whether they want to recognise the independence of disputed regions.[210]

Russia has started work on the establishment of a naval base in Ochamchire by dredging the coast to allow the passage of their larger naval vessels.[211] As a response to the Georgian sea blockade of Abkhazia, in which the Georgian coast guard had been detaining ships heading to and from Abkhazia, Russia warned Georgia against ship seizures and said that a unit of Russian guard boats would provide security for ships bound for Abkhazia.[212]

The extent of Russian influence in Abkhazia has caused some locals to say that Abkhazia is under full Russian control, but they still prefer Russian influence over Georgian.[213][214][215][216]

International involvement

[edit]

The UN has played various roles during the conflict and the peace process: a military role through its observer mission (UNOMIG); dual diplomatic roles through the Security Council and the appointment of a special envoy, succeeded by a special representative to the secretary-general; a humanitarian role (UNHCR and UNOCHA); a development role (UNDP); a human rights role (UNHCHR); and a low-key capacity and confidence-building role (UNV). The UN's position has been that there will be no forcible change of international borders. Any settlement must be freely negotiated and based on autonomy for Abkhazia legitimised by referendum under international observation once the multi-ethnic population has returned.[217]

The OSCE has increasingly engaged in dialogue with officials and civil society representatives in Abkhazia, especially from non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the media, regarding human dimension standards in the region and is considering a presence in Gali. The OSCE expressed concern and condemnation over ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia during the 1994 Budapest Summit decision[218] and later at the Lisbon Summit Declaration in 1996.[219]

The US rejects the unilateral secession of Abkhazia and urges its integration into Georgia as an autonomous unit. In 1998 the US announced its readiness to allocate up to $15 million for rehabilitation of infrastructure in the Gali region if substantial progress is made in the peace process. USAID has already funded some humanitarian initiatives for Abkhazia.[220]

On 22 August 2006, Senator Richard Lugar, then visiting Georgia's capital Tbilisi, joined Georgian politicians in criticism of the Russian peacekeeping mission, stating that "the U.S. administration supports the Georgian government's insistence on the withdrawal of Russian peacekeepers from the conflict zones in Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali district".[221]

On 5 October 2006, Javier Solana, the High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy of the European Union, ruled out the possibility of replacing the Russian peacekeepers with the EU force.[222] On 10 October 2006, EU South Caucasus envoy Peter Semneby noted that "Russia's actions in the Georgia spy row have damaged its credibility as a neutral peacekeeper in the EU's Black Sea neighbourhood."[223]

On 13 October 2006, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted a resolution, based on a Group of Friends of the Secretary-General draft, extending the UNOMIG mission until 15 April 2007. Acknowledging that the "new and tense situation" resulted, at least in part, from the Georgian special forces' operation in the upper Kodori Valley, the resolution urged the country to ensure that no troops unauthorised by the Moscow ceasefire agreement were present in that area. It urged the leadership of the Abkhaz side to address seriously the need for a dignified, secure return of refugees and internally displaced persons and to reassure the local population in the Gali district that their residency rights and identity will be respected. The Georgian side is "once again urged to address seriously legitimate Abkhaz security concerns, to avoid steps that could be seen as threatening and to refrain from militant rhetoric and provocative actions, especially in upper Kodori Valley."[224]

Calling on both parties to follow up on dialogue initiatives, it further urged them to comply fully with all previous agreements regarding non-violence and confidence-building, in particular those concerning the separation of forces. Regarding the disputed role of the peacekeepers from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Council stressed the importance of close, effective cooperation between UNOMIG and that force and looked to all sides to continue to extend the necessary cooperation to them. At the same time, the document reaffirmed the "commitment of all Member States to the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Georgia within its internationally recognised borders".[225]

The HALO Trust, an international non-profit organisation that specialises in the removal of the debris of war, has been active in Abkhazia since 1999 and has completed the removal of landmines in Sukhumi and Gali districts. It declared Abkhazia "mine free" in 2011.[226]

France-based international NGO Première-Urgence has been implementing a food security programme to support the vulnerable populations affected by the frozen conflict for almost 10 years.[227][228]

Russia does not allow the European Union Monitoring Mission in Georgia (EUMM) to enter Abkhazia.[229]

Recognition

[edit]

Abkhazia has been recognised as an independent state only by 5 states: Russia, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Nauru, and Syria. Georgia and other countries consider Abkhazia as Georgia's sovereign territory.[230][231][232][233] Russia was the first country to recognise Abkhazia, which it did after the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. After the Russian recognition, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Nauru, Vanuatu and Tuvalu soon followed suit and recognised Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states. However, in 2013 and 2014, Vanuatu and Tuvalu have scrapped their recognition. Russia invested a significant money in diplomatic strategy to promote recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and display its soft power.[234] However, Russia seems to have stopped investing in the recognition project after 2014. One of the possible reasons might be worsening of the financial situation in Russia following the Russo-Ukrainian War and international sanctions on Russia. Abkhazia started its own campaign to strengthen the relations with the foreign countries and present itself as an independent actor. Abkhaz officials visited a number of countries, including China, Italy, Turkey and Israel. They also met with the officials from South Africa, Jordan and El Salvador, and sent diplomatic notes to other countries, such as Egypt, France, Guatemala and Sri Lanka. This campaign reached its peak in 2017, but subsequently decreased and largely halted with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.[235] It was largely unsuccessful and ended in failure as Syria remains the only country which has recognised Abkhazia and South Ossetia since 2009.[236]

The following is a list of political entities that formally recognise Abkhazia:

UN member states

Russia recognised Abkhazia on 26 August 2008 after the Russo-Georgian War.[237]

Russia recognised Abkhazia on 26 August 2008 after the Russo-Georgian War.[237] Nicaragua recognised Abkhazia on 5 September 2008.[238]

Nicaragua recognised Abkhazia on 5 September 2008.[238] Venezuela recognised Abkhazia on 10 September 2009.[239]

Venezuela recognised Abkhazia on 10 September 2009.[239] Nauru recognised Abkhazia on 15 December 2009.[240]

Nauru recognised Abkhazia on 15 December 2009.[240] Syria recognised Abkhazia on 29 May 2018.[241]

Syria recognised Abkhazia on 29 May 2018.[241]

Partially recognised and unrecognised territories

South Ossetia recognised Abkhazia on 17 November 2006.[163]

South Ossetia recognised Abkhazia on 17 November 2006.[163] Transnistria recognised Abkhazia on 17 November 2006.[163]

Transnistria recognised Abkhazia on 17 November 2006.[163]

Former recognition

Vanuatu recognised Abkhazia on 23 May 2011,[242] but withdrew recognition on 20 May 2013.[243]

Vanuatu recognised Abkhazia on 23 May 2011,[242] but withdrew recognition on 20 May 2013.[243] Tuvalu recognised Abkhazia on 18 September 2011, but withdrew recognition on 31 March 2014.[244]

Tuvalu recognised Abkhazia on 18 September 2011, but withdrew recognition on 31 March 2014.[244] Artsakh recognised Abkhazia on 17 November 2006.[245] Self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh dissolved in 2023.

Artsakh recognised Abkhazia on 17 November 2006.[245] Self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh dissolved in 2023.

Proposals on entry into Russian Federation

[edit]Since the 1992–1993 War in Abkhazia, there have been several proposals voiced by the separatist Abkhaz government and the Russian government for Abkhazia to become part of the Russian Federation, which have been opposed by the Georgian government and the government-in-exile of Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia. One of the early proposals was voiced before the war, in March 1989, when the Abkhaz ethno-nationalist organisation Aidgylara issued the Lykhny Appeal, calling for Abkhazia to become part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. This is thought to be a starting point for the Abkhazia conflict between the separatists and local Georgian population in Abkhazia. After the war, on 18 November 1993, a month after its ending and ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia, the leader of Abkhazia Vladislav Ardzinba proposed to hold a referendum to join the Russian Federation.[246] In 2001, a similar desire was voiced by Abkhazia's Prime Minister Anri Jergenia, who said that Abkhazia was preparing to join Russia and that it was going to hold a referendum on that issue.[247]

In October 2022, in an interview to the Russian TV, President of Abkhazia Aslan Bzhania declared Abkhazia's readiness to host a Russian navy and join the Russia-Belarus Union State.[248] However, the proposal has been criticised as impractical since Belarus does not recognise Abkhazia as a sovereign state and considers it to be part of Georgia.[249]

In August 2023, Deputy Chair of Russian Security Council Dmitry Medvedev also voiced support for these proposals, accusing Georgia of "escalating tensions" by its potential membership to the NATO, and saying that there were "good reasons" for Abkhazia and South Ossetia to join Russia.[250] Medvedev also mocked Georgia's desire to restore its territorial integrity, saying that "Georgia can only be united as part of Russia".[251]

Georgia criticised the proposals for Abkhazia's entry into the Russian Federation and Union State. In 2014, Georgia's Foreign Ministry issued a statement, calling the Russia-Abkhazia treaty on integration a de facto annexation.[252]

Geography and climate

[edit]

Abkhazia covers an area of about 8,665 km2 (3,346 sq mi) at the western end of Georgia.[3][253][254] The Caucasus Mountains to the north and northeast separate Abkhazia and the Russian Federation. To the east and southeast, Abkhazia is bounded by the Georgian region of Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti; and on the south and southwest by the Black Sea.[citation needed]

Abkhazia is diverse geographically with lowlands stretching to the extremely mountainous north. The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range runs along the region's northern border, with its spurs – the Gagra, Bzyb and Kodori ranges – dividing the area into a number of deep, well-watered valleys. The highest peaks of Abkhazia are in the northeast and east and several exceed 4,000 metres (13,123 ft) above sea level. Abkhazia's landscape ranges from coastal forests and citrus plantations to permanent snows and glaciers in the north of the region. Although Abkhazia's complex topographic setting has spared most of the territory from significant human development, its cultivated fertile lands produce tea, tobacco, wine and fruits, a mainstay of the local agricultural sector.[citation needed]

Abkhazia is richly irrigated by small rivers originating in the Caucasus Mountains. Chief of these are: Kodori, Bzyb, Ghalidzga, and Gumista. The Psou River separates the region from Russia, and the Inguri serves as a boundary between Abkhazia and Georgia proper. There are several periglacial and crater lakes in mountainous Abkhazia. Lake Ritsa is the most important of them.[citation needed]

Because of Abkhazia's proximity to the Black Sea and the shield of the Caucasus Mountains, the region's climate is very mild. The coastal areas of the republic have a subtropical climate, where the average annual temperature in most regions is around 15 °C (59 °F), and the average January temperature remains above freezing.[3] The climate at higher elevations varies from maritime mountainous to cold and summerless. Also, due to its position on the windward slopes of the Caucasus, Abkhazia receives high amounts of precipitation,[3] though humidity decreases further inland. The annual precipitation varies from 1,200–1,400 mm (47.2–55.1 in)[3] along the coast to 1,700–3,500 mm (66.9–137.8 in) in the higher mountainous areas. The mountains of Abkhazia receive significant amounts of snow.[citation needed]

The world's deepest known cave, Veryovkina Cave, is located in Abkhazia's western Caucasus mountains. The latest survey (as of March 2018) has measured the vertical extent of this cave system as 2,212 metres (7,257 ft) between its highest and lowest explored points.[citation needed]

The lowland regions used to be covered by swaths of oak, beech, and hornbeam, which have since been cleared.[3]

There are two main entrances into Abkhazia. The southern entrance is at the Inguri bridge, a short distance from the city of Zugdidi. The northern entrance ("Psou") is in the town of Leselidze. Owing to the situation with a recognition controversy, many foreign governments advise their citizens against travelling to Abkhazia.[255] According to President Raul Khajimba, over the summer of 2015, thousands of tourists visited Abkhazia.[256][unreliable source?]

Politics and government

[edit]Republic of Abkhazia

[edit]Abkhazia is a presidential republic.[257] Legislative powers are vested in the People's Assembly, which consists of 35 elected members. The last parliamentary elections were held in March 2022. Ethnicities other than Abkhaz (Armenians, Russians and Georgians) are claimed to be under-represented in the Assembly.[128] Most refugees from the 1992–1993 war (mainly ethnic Georgians) have not been able to return and have thus been excluded from the political process.[258] Some refugees have been allowed to return, in particular in the Gali district where 98% of the population is Georgian as it was before the ethnic cleansing, however, they have been stripped of the voting and other rights. As such, during the 2021 local elections, only 900 eligible voters were registered in the Gali district, despite the 30,259 residents in the area. The territory of the Gali district has also been diminished through addition of some of its lands to Tkvarcheli and Ochamchire districts.[259]

Russia has a major military and economic presence in Abkhazia, and the relationship between the two has been described as asymmetrical, with Abkhazia being heavily dependent on Russia. Half of Abkhazia's budget comes from Russian funding (with most of financial aid coming in the form of loans), much of its state structure is integrated with Russia, it uses the Russian ruble, its foreign policy is coordinated with Russia, and a majority of its citizens have Russian passports as a result of Russia's passportization policy. Abkhazia has adopted Russian technical and commercial standards, and large part of its infrastructure is owned by Russian companies, with Russia heavily investing in the military infrastructure. The 2014 Treaty on Alliance and Strategic Partnership obliges Abkhazia to coordinate its foreign policy with Russia and merge the armed forces.[260][261] As such, under pressure from Russia, Abkhazia joined Russia in imposing sanctions on Turkey in 2016, becoming Russia's only ally to do so.[262][263] Abkhazian officials have stated that they have given the Russian Federation the responsibility of representing their interests abroad.[264] Some have described Abkhazia as Russia's protectorate with a strong and one-sided dependence.[261]

According to a 2010 study published by the University of Colorado Boulder, the vast majority of Abkhazia's population supports independence, while a smaller number is in favour of joining the Russian Federation. Support for reunification with Georgia is very low.[265]. Among ethnic Abkhaz, explicit support for reunification with Georgia is around 1%; a similar figure can be found among ethnic Russians and Armenians as well.[266]

Harmonisation of laws with Russia

[edit]In 2014, separatist Republic of Abkhazia and Russian Federation signed the "Treaty of Alliance and Strategic Partnership" with Russia. Based on this treaty, in November 2020, Abkhazia launched a program on the "formation of common social and economic space" with Russia to make Abkhaz laws and administrative measures more similar to Russian ones in social, economic, health and political spheres.[267] On 15 August 2024, the Russian Deputy Minister of Economic Development Dmitry Volvach said that the process of Abkhazia's harmonisation of its laws with Russia was "almost complete".[268]

Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia

[edit]

The Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia is the government in exile that Georgia recognises as the legal government of Abkhazia. This pro-Georgian government maintained a foothold on Abkhazian territory, in the upper Kodori Valley from July 2006 until it was forced out by fighting in August 2008. This government is also partly responsible for the affairs of some 250,000 IDPs, forced to leave Abkhazia following the War in Abkhazia and ethnic cleansing that followed.[269][270] The current Head of the Government is Vakhtang Kolbaia.[citation needed]

During the War in Abkhazia, the Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia (at the time the Georgian faction of the "Council of Ministers of Abkhazia") left Abkhazia after the Abkhaz separatist forces took control of the region's capital Sukhumi and relocated to Georgia's capital Tbilisi where it operated as the Government of Abkhazia in exile for almost 13 years. During this period, the Government of Abkhazia in exile, led by Tamaz Nadareishvili, was known for a hard-line stance towards the Abkhaz problem and frequently voiced their opinion that the solution to the conflict can be attained only through Georgia's military response to secessionism.[271] Later, Nadareishvili's administration was implicated in some internal controversies and had not taken an active part in the politics of Abkhazia[citation needed] until a new chairman, Irakli Alasania, was appointed by President of Georgia, Mikheil Saakashvili, his envoy in the peace talks over Abkhazia.[citation needed]

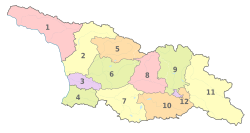

Administrative divisions

[edit]

The Republic of Abkhazia is divided into seven raions (districts) named after their primary cities: Gagra, Gudauta, Sukhumi, Ochamchira, Gulripshi, Tkvarcheli and Gali. These districts remain mostly unchanged since the break-up of the Soviet Union, with the exception of the Tkvarcheli District, created in 1995 from parts of the Ochamchira and Gali districts.[272]

The President of the Republic appoints districts' heads from those elected to the districts' assemblies. There are elected village assemblies whose heads are appointed by the districts' heads.[128]

The administrative subdivisions under Georgian law are identical to the ones outlined above, except for the new Tkvarcheli district.[citation needed]

Military

[edit]The Abkhazian Armed Forces are the military of the Republic of Abkhazia. The basis of the Abkhazian armed forces was formed by the ethnically Abkhaz National Guard, which was established in early 1992. Most of their weapons come from the former Russian airborne division base in Gudauta.[273][274] The Abkhazian military is primarily a ground force, but includes small sea and air units. Russia deploys its own military units as part of the 7th Military Base in Abkhazia.[275] These units are reportedly subordinate to the Russian 49th Army and include both ground elements and air defence assets.[276]

The Abkhazian Armed Forces are composed of:

- The Abkhazian Army with a permanent force of around 5,000, but with reservists and paramilitary personnel this may increase to up to 50,000 in times of military conflict. The exact numbers and the type of equipment used remain unverifiable.

- The Abkhazian Navy that consists of three divisions based in Sukhumi, Ochamchire and Pitsunda, but the Russian coast guard patrols their waters.[citation needed]

- The Abkhazian Air Force, a small unit consisting of a few fighter aircraft and helicopters.

Economy

[edit]The economy of Abkhazia is integrated with Russia as outlined in a bilateral agreement published in November 2014. The country uses the Russian ruble as its currency, and the two countries share a common economic and customs union.[277] Abkhazia has experienced a modest economic upswing since the 2008 South Ossetia war and Russia's subsequent recognition of Abkhazia's independence. About half of Abkhazia's state budget is financed with aid money from Russia.[278]

Tourism is a key industry and, according to Abkhazia's authorities, almost a million tourists (mainly from Russia) came to Abkhazia in 2007.[279] Abkhazia exports wine and fruits, especially tangerines and hazelnuts.[280] Electricity is largely supplied by the Inguri hydroelectric power station located on the Inguri River between Abkhazia and Georgia (proper) and operated jointly by both parties.[281]

In the first half of 2012, the principal trading partners of Abkhazia were Russia (64%) and Turkey (18%).[282] The CIS economic sanctions imposed on Abkhazia in 1996 are still formally in force, but Russia announced on 6 March 2008 that it would no longer participate in them, declaring them "outdated, impeding the socio-economic development of the region, and causing unjustified hardship for the people of Abkhazia". Russia also called on other CIS members to undertake similar steps,[283] but met with protests from Tbilisi and lack of support from the other CIS countries.[284]

Despite the controversial status of the territory and its damaged infrastructure, tourism in Abkhazia grew following the Russian recognition of Abkhazian independence in 2008 due to the arrival of Russian tourists. In 2009 the number of Russian tourists in Abkhazia increased by 20% and the total number of Russian tourists reached 1 million.[285][286] After the tourist boom many Russian businesses began to invest money in Abkhazian tourist infrastructure. With the main highway of the country being rebuilt in 2014 many damaged hotels in Gagra are either being restored or demolished. In 2014, 1.16 million Russian tourists visited Abkhazia.[287]

Demographics

[edit]According to the last census in 2011 Abkhazia had 240,705 inhabitants.[288] The Department of Statistics of Georgia estimated Abkhazia's population to be approximately 179,000 in 2003, and 178,000 in 2005 (the last year when such estimates were published in Georgia).[289] Encyclopædia Britannica estimates the population in 2007 at 180,000[290] and the International Crisis Group estimated Abkhazia's total population in 2006 to be between 157,000 and 190,000 (or between 180,000 and 220,000 as estimated by UNDP in 1998).[291]

Ethnicity

[edit]The ethnic composition of Abkhazia has played a central role in the Georgian-Abkhazian conflict. The 1992–1993 war with Georgia resulted in the expulsion and flight of over half of the republic's population, which had numbered 525,061 in the 1989 census.[117] The population of Abkhazia remains ethnically very diverse, even after the 1992–1993 war. At present the population of Abkhazia is mainly made up of ethnic Abkhaz (50.7% according to the 2011 census), Russians, Armenians, Georgians (mostly Mingrelians, but also Svans), and Greeks.[288] Other ethnicities include Ukrainians, Belarusians, Ossetians, Tatars, Turks, Roma and Estonians.[292]

Greeks constituted a significant minority in the area in the early 1920s (50,000), and remained a major ethnic group until 1945, when they were deported to Central Asia.[293] Under the Soviet Union, the Russian, Armenian, and Georgian populations grew faster than the Abkhaz population, due to large-scale enforced migration, especially under the rule of Joseph Stalin and Lavrenty Beria.[77]

At the time of the 1989 census, Abkhazia's Georgian population numbered 239,872, forming around 45.7% of the population, and the Armenian population was 77,000.[117][294] Due to ethnic cleansing and displacement due to people fleeing the 1992–1993 war, the Georgian population, and to a lesser extent the Russian and Armenian populations, has greatly declined.[290] In 2003 Armenians formed the second-largest minority group in Abkhazia (closely matching the Georgians), numbering 44,869.[117] By the time of the 2011 census, Georgians formed the second-largest minority group with a population of 46,455.[294] Despite the official numbers, unofficial sources estimate that the Abkhaz and Armenian communities are roughly equal in number.[295]

In the wake of the Syrian civil war, Abkhazia granted refugee status to a few hundred Syrians with Abkhaz, Abazin and Circassian ancestry.[295] Facing a growing Armenian community, this move has been linked with the wish of the ruling Abkhaz —who have often been in the minority on their territory— to tilt the demographic balance in favour of the titular nation.[295]

Diaspora

[edit]Thousands of Abkhaz, known as muhajirun, were exiled to the Ottoman Empire in the mid-19th century after resisting the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. Today, Turkey is home to the world's largest Abkhaz diaspora community. Size estimates vary – diaspora leaders say 1 million people; Abkhaz estimates range from 150,000 to 500,000.[296][297]

Religion

[edit]

A majority of inhabitants of Abkhazia are Christian (Eastern Orthodox (see also: Abkhazian Orthodox Church) and Armenian Apostolic) while a significant minority are Sunni Muslim.[299] The Abkhaz Native Religion has undergone a strong revival in recent decades.[300] There is a very small number of adherents of Judaism, Jehovah's Witnesses and new religious movements.[298] The Jehovah's Witnesses organisation has officially been banned since 1995, though the decree is not currently enforced.[301]

According to the constitution of Abkhazia, the adherents of all religions have equal rights before the law.[302]

According to a survey held in 2003, 60% of respondents identified themselves as Christian, 16% as Muslim, 8% as atheist or irreligious, 8% as adhering to the traditional Abkhazian religion or as Pagan, 2% as follower of other religions and 6% as undecided.[298]

Language

[edit]Article 6 of the Constitution of Abkhazia states:

The official language of the Republic of Abkhazia shall be the Abkhazian language. The Russian language, equally with the Abkhazian language, shall be recognized as a language of State and other institutions. The State shall guarantee the right to freely use the mother language for all the ethnic groups residing in Abkhazia.[303]

The languages spoken in Abkhazia are Abkhaz, Russian, the Kartvelian languages Mingrelian and Svan, Armenian, and Greek.[304] The Autonomous Republic passed a law in 2007 defining the Abkhaz language as the only state language of Abkhazia.[305] As such, Abkhaz is the required language for legislative and executive council debates (with translation from and to Russian) and at least half of the text of all magazines and newspapers must be in Abkhaz.[305]

Despite the official status of Abkhaz, the dominance of other languages within Abkhazia, especially Russian, is so great that experts called it an "endangered language" in 2004.[306] During the Soviet era, language instruction would begin in schools in Abkhaz, only to switch to Russian for the majority of required schooling.[306] The government of the Republic is attempting to institute Abkhaz-only primary education but there has been limited success due to a lack of facilities and educational materials.[305] The primary schools in Kartvelian-speaking areas switched from Georgian to Russian in 2016.[307]

Nationality issues

[edit]Passportization by Russian Federation

[edit]

After the break-up of the Soviet Union, many Abkhazians kept their Soviet passports, even after a decade, and used them to eventually apply for Russian citizenship.[308]

Before 2002, Russian law allowed residents of former Soviet Union to apply for citizenship if they had not become citizens of their newly independent states. The procedure was extremely complex. The new citizenship law of Russia adopted on 31 May 2002 introduced a simplified procedure of citizenship acquisition for former citizens of the Soviet Union regardless of their place of residence. In Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the application process was simplified even further, and people could apply even without leaving their homes. Russian non-governmental organisations with close ties to Russian officialdom simply took their papers to a nearby Russian city for processing.[309]

Abkhazians began mass acquisition of Russian passports in 2002. It is reported that the public organisation the Congress of Russian Communities of Abkhazia started collecting Abkhazians' Soviet-era travel documents. It then sent them to a consular department specially set up by Russian Foreign Ministry officials in the city of Sochi. After they were checked, Abkhazian applicants were granted Russian citizenship. By 25 June 2002, an estimated 150,000 people in Abkhazia had acquired the new passports, joining 50,000 who already possessed Russian citizenship. The Sukhum authorities, although officially not involved in the registration for Russian nationality process, openly encouraged it. Government officials said privately that President Putin's administration agreed with the passport acquisition during Abkhazia's prime minister Djergenia's visit to Moscow in May 2002.[308] When the "passportisation" policy was launched in 2002, even Russia recognised Abkhazia as part of Georgia at that time. Russia's extraterritorial naturalisation practice in South Ossetia and Abkhazia constituted an intervention contrary to international law and it violated Georgia's territorial sovereignty.[310]

The passportisation caused outrage in Tbilisi, worsening its already shaky relations with Russia. The Georgian Foreign Ministry issued a statement insisting that Abkhazians were citizens of Georgia and calling the passport allocation an "unprecedented illegal campaign". President Eduard Shevardnadze said that he would be asking his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, for an explanation. The speaker of parliament Nino Burjanadze said that she would raise the matter at the forthcoming OSCE parliamentary assembly.[308]

1 February 2011 was the last day in the post-Soviet era when a passport of USSR was valid for crossing the Russian-Abkhaz border. According to the staff of Abkhazia's passport and visa service, there were about two to three thousand mostly elderly people left with Soviet passports who had no chance of acquiring new documents. These people were not able to get Russian citizenship. But they can first get an internal Abkhaz passport and then a travelling passport to visit Russia.[311]

Issue of ethnic Georgians

[edit]In 2005, citing the need to integrate ethnic Georgian residents of eastern districts of Abkhazia, the then leadership of Abkhazia showed signs of a softening stance towards granting of citizenship to the residents of Gali, Ochamchire and Tkvarcheli districts.[312]