Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nitrobacter

View on Wikipedia

| Nitrobacter | |

|---|---|

| |

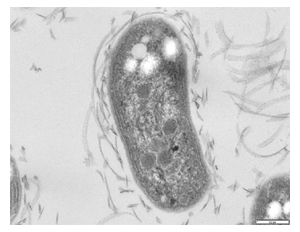

| TEM image of Nitrobacter winogradskyi strain Nb-255 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Pseudomonadati |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Alphaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Hyphomicrobiales |

| Family: | Nitrobacteraceae |

| Genus: | Nitrobacter Winogradsky 1892 |

| Type species | |

| Nitrobacter winogradskyi | |

| Species | |

Nitrobacter is a genus comprising rod-shaped, gram-negative, and chemoautotrophic bacteria.[1] The name Nitrobacter derives from the Latin neuter gender noun nitrum, nitri, alkalis; the Ancient Greek noun βακτηρία, βακτηρίᾱς, rod. They are non-motile and reproduce via budding or binary fission.[2][3] Nitrobacter cells are obligate aerobes and have a doubling time of about 13 hours.[1]

Nitrobacter play an important role in the nitrogen cycle by oxidizing nitrite into nitrate in soil and marine systems.[2] Unlike plants, where electron transfer in photosynthesis provides the energy for carbon fixation, Nitrobacter uses energy from the oxidation of nitrite ions, NO2−, into nitrate ions, NO3−, to fulfill their energy needs. Nitrobacter fix carbon dioxide via the Calvin cycle for their carbon requirements.[1] Nitrobacter belongs to the Alphaproteobacteria class of the Pseudomonadota.[3][4]

Morphology and characteristics

[edit]Nitrobacter are gram-negative bacteria and are either rod-shaped, pear-shaped or pleomorphic.[1][2] They are typically 0.5–0.9 μm in width and 1.0–2.0 μm in length and have an intra-cytomembrane polar cap.[5][2] Due to the presence of cytochromes c, they are often yellow in cell suspensions.[5] The nitrate oxidizing system on membranes is cytoplasmic.[2] Nitrobacter cells have been shown to recover following extreme carbon dioxide exposure and are non-motile.[6][5][2]

Phylogeny

[edit]16s rRNA sequence analysis phylogenetically places Nitrobacter within the class of Alphaproteobacteria. Pairwise evolutionary distance measurements within the genus are low compared to those found in other genera, and are less than 1%.[6] Nitrobacter are also closely related to other species within the Alphaproteobacteria, including the photosynthetic Rhodopseudomonas palustris, the root-nodulating Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Blastobacter denitrificans, and the human pathogens Afipia felis and Afipia clevelandensis.[6] Bacteria within the genus Nitrobacter are presumed to have arisen on multiple occasions from a photosynthetic ancestor, and for individual nitrifying genera and species there is evidence that the nitrification phenotype evolved separately from that found in photosynthetic bacteria.[6]

All known nitrite-oxidizing prokaryotes are restricted to a handful of phylogenetic groups. This includes the genus Nitrospira within the phylum Nitrospirota,[7] and the genus Nitrolancetus from the phylum Chloroflexota (formerly Chloroflexi).[8] Before 2004, nitrite oxidation was believed to only occur within Pseudomonadota; it is likely that further scientific inquiry will expand the list of known nitrite-oxidizing species.[9] The low diversity of species oxidizing nitrite oxidation contrasts with other processes associated with the nitrogen cycle in the ocean, such as denitrification and N-fixation, where a diverse range of taxa perform analogous functions.[8]

Nitrification

[edit]Nitrification is a crucial component of the nitrogen cycle, especially in the oceans. The production of nitrate (NO3−) by oxidation of nitrite (NO2−) is accomplished by nitrification - the process that produces the inorganic nitrogen that meets much of the demand of marine oxygenic, photosynthetic organisms such as phytoplankton, particularly in areas of upwelling. For this reason, nitrification supplies much of the nitrogen that fuels planktonic primary production in the world's oceans. Nitrification is estimated to be the source of half of the nitrate consumed by phytoplankton globally.[10] Phytoplankton are major contributors to oceanic production, and are therefore important for the biological pump which exports carbon and other particulate organic matter from the surface waters of the world's oceans. The process of nitrification is crucial for separating recycled production from production leading to export. Biologically metabolized nitrogen returns to the inorganic dissolved nitrogen pool in the form of ammonia. Microbe-mediated nitrification converts that ammonia into nitrate, which can subsequently be taken up by phytoplankton and recycled.[10]

The nitrite oxidation reaction performed by the Nitrobacter is as follows;

NO2− + H2O → NO3− + 2H+ + 2e−

2H+ + 2e− + ½O2 → H2O[9]

The Gibbs' Free Energy yield for nitrite oxidation is:

ΔGο = -74 kJ mol−1 NO2−

In the oceans, nitrite-oxidizing bacteria such as Nitrobacter are usually found in close proximity to ammonia-oxidizing bacteria.[11] These two reactions together make up the process of nitrification. The nitrite-oxidation reaction generally proceeds more quickly in ocean waters, and therefore is not a rate-limiting step in nitrification. For this reason, it is rare for nitrite to accumulate in ocean waters.

The two-step conversion of ammonia to nitrate observed in ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, ammonia-oxidizing archaea and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (such as Nitrobacter) is puzzling to researchers.[12][13] Complete nitrification, the conversion of ammonia to nitrate in a single step known as comammox, has an energy yield (∆G°′) of −349 kJ mol−1 NH3, while the energy yields for the ammonia-oxidation and nitrite-oxidation steps of the observed two-step reaction are −275 kJ mol−1 NH3, and −74 kJ mol−1 NO2−, respectively.[12] These values indicate that it would be energetically favourable for an organism to carry out complete nitrification from ammonia to nitrate (comammox), rather than conduct only one of the two steps. The evolutionary motivation for a decoupled, two-step nitrification reaction is an area of ongoing research. In 2015, it was discovered that the species Nitrospira inopinata possesses all the enzymes required for carrying out complete nitrification in one step, suggesting that this reaction does occur.[12][13] This discovery raises questions about evolutionary capability of Nitrobacter to conduct only nitrite-oxidation.

Metabolism and growth

[edit]Members of the genus Nitrobacter use nitrite as a source of electrons (reductant), nitrite as a source of energy, and CO2 as a carbon source.[11] Nitrite is not a particularly favourable substrate from which to gain energy. Thermodynamically, nitrite oxidation gives a yield (∆G°′) of only -74 kJ mol−1 NO2−.[12] As a result, Nitrobacter has developed a highly specialized metabolism to derive energy from the oxidation of nitrite.

Cells in the genus Nitrobacter reproduce by budding or binary fission.[5][2] Carboxysomes, which aid carbon fixation, are found in lithoautotrophically and mixotrophically grown cells. Additional energy conserving inclusions are PHB granules and polyphosphates. When both nitrite and organic substances are present, cells can exhibit biphasic growth; first the nitrite is used and after a lag phase, organic matter is oxidized. Chemoorganotroph growth is slow and unbalanced, thus more poly-β-hydroxybutyrate granules are seen that distort the shape and size of the cells.

The enzyme responsible for the oxidation of nitrite to nitrate in members of the genus Nitrobacter is nitrite oxidoreductase (NXR), which is encoded by the gene nxrA.[14] NXR is composed of two subunits, and likely forms an αβ-heterodimer.[15] The enzyme exists within the cell on specialized membranes in the cytoplasm that can be folded into vesicles or tubes.[15] The α-subunit is thought to be the location of nitrite oxidation, and the β-subunit is an electron channel from the membrane.[15] The direction of the reaction catalyzed by NXR can be reversed depending on oxygen concentrations.[15] The region of the nxrA gene which encodes for the β-subunit of the NXR enzyme is similar in sequence to the iron-sulfur centers of bacterial ferredoxins, and to the β-subunit of the enzyme nitrate reductase, found in Escherichia coli.[16]

Ecology and distribution

[edit]

The genus Nitrobacter is widely distributed in both aquatic and terrestrial environments.[2] Nitrifying bacteria have an optimum growth between 77 and 86 °F (25 and 30 °C), and cannot survive past the upper limit of 120 °F (49 °C) or the lower limit of 32 °F (0 °C).[1] This limits their distribution even though they can be found in a wide variety of habitats.[1] Cells in the genus Nitrobacter have an optimum pH for growth between 7.3 and 7.5.[1] According to Grundmann, Nitrobacter seem to grow optimally at 38 °C and at a pH of 7.9, but Holt states that Nitrobacter grow optimally at 28 °C and within a pH range of 5.8 to 8.5, although they have a pH optima between 7.6 and 7.8.[17][3]

The primary ecological role of members of the genus Nitrobacter is to oxidize nitrite to nitrate, a primary source of inorganic nitrogen for plants. This role is also essential in aquaponics.[1][18] Since all members in the genus Nitrobacter are obligate aerobes, oxygen along with phosphorus tend to be factors that limit their capability to perform nitrite oxidation.[1] One of the major impacts of nitrifying bacteria such as ammonia-oxidizing Nitrosomonas and nitrite-oxidizing Nitrobacter in both oceanic and terrestrial ecosystems is on the process of eutrophication.[19]

The distribution and differences in nitrification rates across different species of Nitrobacter may be attributed to differences in the plasmids among species, as data presented in Schutt (1990) imply, habitat-specific plasmid DNA was induced by adaptation for some of the lakes that were investigated.[20] A follow-up study performed by Navarro et al. (1995) showed that various Nitrobacter populations carry two large plasmids.[19] In conjunction with Schutts’ (1990) study, Navarro et al. (1995) illustrated genomic features that may play crucial roles in determining the distribution and ecological impact of members of the genus Nitrobacter. Nitrifying bacteria in general tend to be less abundant than their heterotrophic counterparts, as the oxidizing reactions they perform have a low energy yield and most of their energy production goes toward carbon-fixation rather than growth and reproduction.[1]

History

[edit]

In 1890, Ukrainian-Russian microbiologist Sergei Winogradsky isolated the first pure cultures of nitrifying bacteria which are capable of growth in the absence of organic matter and sunlight. The exclusion of organic material by Winogradsky in the preparation of his cultures is recognized as a contributing factor to his success in isolating the microbes (attempts to isolate pure cultures are difficult due to a tendency for heterotrophic organisms to overtake plates with any presence of organic material[21]).[22] In 1891, English chemist Robert Warington proposed a two-stage mechanism for nitrification, mediated by two distinct genera of bacteria. The first stage proposed was the conversion of ammonia to nitrite, and the second the oxidation of nitrite to nitrate.[23] Winogradsky named the bacteria responsible for the oxidation of nitrite to nitrate Nitrobacter in his subsequent study on microbial nitrification in 1892.[24] Winslow et al. proposed the type species Nitrobacter winogradsky in 1917.[25] The species was officially recognized in 1980.[26]

Main Species

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Nitrifying Bacteria Facts".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Spleck, Eva; Bock, Eberhard (2004). Bergey's Manual ® of Systematic Bacteriology Volume Two: The Proteobacteria, Part A Introductory Essays. Springer. pp. 149–153. ISBN 978-0-387-241-43-2.

- ^ a b c Grundmann, GL; Neyra, M; Normand, P (2000). "High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of NO2--oxidizing Nitrobacter species using the rrs-rrl IGS sequence and rrl genes". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 50 (Pt 5): 1893–8. doi:10.1099/00207713-50-5-1893. PMID 11034501.

- ^ Grunditz, C; Dalhammar, G (2001). "Development of nitrification inhibition assays using pure cultures of Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter". Water Research. 35 (2): 433–40. Bibcode:2001WatRe..35..433G. doi:10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00312-2. PMID 11228996.

- ^ a b c d Pillay, B.; Roth, G.; Oellermann, A. (1989). "Cultural characteristics and identification of marine nitrifying bacteria from a closed prawnculture system in Durban". South African Journal of Marine Science. 8 (1): 333–343. doi:10.2989/02577618909504573.

- ^ a b c d Teske, A; Alm, E; Regan, J M; Toze, S; Rittmann, B E; Stahl, D A (1994-11-01). "Evolutionary relationships among ammonia- and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria". Journal of Bacteriology. 176 (21): 6623–6630. doi:10.1128/jb.176.21.6623-6630.1994. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 197018. PMID 7961414.

- ^ Ehrich, Silke; Behrens, Doris; Lebedeva, Elena; Ludwig, Wolfgang; Bock, Eberhard (1995). "A new obligately chemolithoautotrophic, nitrite-oxidizing bacterium, Nitrospira moscoviensis sp. nov. and its phylogenetic relationship". Archives of Microbiology. 164 (1): 16–23. Bibcode:1995ArMic.164...16E. doi:10.1007/bf02568729. PMID 7646315.

- ^ a b Sorokin, Dimitry Y; Lücker, Sebastian; Vejmelkova, Dana; Kostrikina, Nadezhda A; Kleerebezem, Robbert; Rijpstra, W Irene C; Damsté, Jaap S Sinninghe; Le Paslier, Denis; Muyzer, Gerard (2017-03-09). "Nitrification expanded: discovery, physiology and genomics of a nitrite-oxidizing bacterium from the phylum Chloroflexi". The ISME Journal. 6 (12): 2245–2256. doi:10.1038/ismej.2012.70. ISSN 1751-7362. PMC 3504966. PMID 22763649.

- ^ a b Zehr, Jonathan P.; Kudela, Raphael M. (2011-01-01). "Nitrogen cycle of the open ocean: from genes to ecosystems". Annual Review of Marine Science. 3: 197–225. Bibcode:2011ARMS....3..197Z. doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142819. ISSN 1941-1405. PMID 21329204.

- ^ a b Yool, Andrew; Martin, Adrian P.; Fernández, Camila; Clark, Darren R. (2007-06-21). "The significance of nitrification for oceanic new production". Nature. 447 (7147): 999–1002. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..999Y. doi:10.1038/nature05885. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17581584.

- ^ a b "Nitrification Network". nitrificationnetwork.org. Archived from the original on 2018-05-02. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b c d Daims, Holger; Lebedeva, Elena V.; Pjevac, Petra; Han, Ping; Herbold, Craig; Albertsen, Mads; Jehmlich, Nico; Palatinszky, Marton; Vierheilig, Julia (2015-12-24). "Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria". Nature. 528 (7583): 504–509. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..504D. doi:10.1038/nature16461. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5152751. PMID 26610024.

- ^ a b van Kessel, Maartje A. H. J.; Speth, Daan R.; Albertsen, Mads; Nielsen, Per H.; Op den Camp, Huub J. M.; Kartal, Boran; Jetten, Mike S. M.; Lücker, Sebastian (2015-12-24). "Complete nitrification by a single microorganism". Nature. 528 (7583): 555–559. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..555V. doi:10.1038/nature16459. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 4878690. PMID 26610025.

- ^ Poly, Franck; Wertz, Sophie; Brothier, Elisabeth; Degrange, Valérie (2008-01-01). "First exploration of Nitrobacter diversity in soils by a PCR cloning-sequencing approach targeting functional gene nxrA". FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 63 (1): 132–140. Bibcode:2008FEMME..63..132P. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00404.x. ISSN 1574-6941. PMID 18031541.

- ^ a b c d Garrity, George M. (2001-01-01). Bergey's Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 462. ISBN 9780387241456.

- ^ Kirstein, K.; Bock, E. (1993-01-01). "Close genetic relationship between Nitrobacter hamburgensis nitrite oxidoreductase and Escherichia coli nitrate reductases". Archives of Microbiology. 160 (6): 447–453. Bibcode:1993ArMic.160..447K. doi:10.1007/bf00245305. ISSN 0302-8933. PMID 8297210.

- ^ a b c d e Holt, John G.; Hendricks Bergey, David (1993). R.S. Breed (ed.). Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology (9th ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-683-00603-2.

- ^ Hu, Zhen; Lee, Jae Woo; Chandran, Kartik; Kim, Sungpyo; Brotto, Ariane Coelho; Khanal, Samir Kumar (2015-07-01). "Effect of plant species on nitrogen recovery in aquaponics". Bioresource Technology. International Conference on Emerging Trends in Biotechnology. 188: 92–98. Bibcode:2015BiTec.188...92H. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2015.01.013. PMID 25650140.

- ^ a b Navarro, E.; Degrange, V.; Bardin, R. (1995-01-01). Balvay, Gérard (ed.). Space Partition within Aquatic Ecosystems. Developments in Hydrobiology. Springer Netherlands. pp. 43–48. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-0293-3_3. ISBN 9789401041294.

- ^ Schütt, Christian (1990-01-01). "Plasmids and Their Role in Natural Aquatic Bacterial Communities". In Overbeck, Jürgen; Chróst, Ryszard J. (eds.). Aquatic Microbial Ecology. Brock/Springer Series in Contemporary Bioscience. Springer New York. pp. 160–183. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-3382-4_7. ISBN 9781461279914.

- ^ Pepper, Ian L.; Gerba, Charles P. (2015), "Cultural Methods", Environmental Microbiology, Elsevier, pp. 195–212, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-394626-3.00010-7, ISBN 978-0-12-394626-3, retrieved 2024-04-21

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Winogradsky, Sergei (1890). "Recherches sur les Organismes de la Nitrification". Milestone in Microbiology. 110: 1013–1016.

- ^ "Investigations upon Nitrification and the Nitrifying Organisms". Science. 18: 48–52. 1891.

- ^ Winogradsky, Sergei (1892). "Contributions a la morphologie des organismes de la nitrification". Archives of Biological Science. 1: 86–137.

- ^ Winslow, Charles-Edward (1917). "The Characterization and Classification of Bacterial Types". Science. 39 (994): 77–91. doi:10.1126/science.39.994.77. PMID 17787843.

- ^ D., Skerman, V. B.; Vicki., Mcgowan; Andrews., Sneath, Peter Henry; committee., International committee on systematic bacteriology. Judicial commission. Ad hoc (1989-01-01). Approved lists of bacterial names. American society for microbiology. ISBN 9781555810146. OCLC 889445817.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)