Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Normal (geometry)

View on Wikipedia

In geometry, a normal is an object (e.g. a line, ray, or vector) that is perpendicular to a given object. For example, the normal line to a plane curve at a given point is the infinite straight line perpendicular to the tangent line to the curve at the point.

A normal vector is a vector perpendicular to a given object at a particular point. A normal vector of length one is called a unit normal vector or normal direction. A curvature vector is a normal vector whose length is the curvature of the object. Multiplying a normal vector by −1 results in the opposite vector, which may be used for indicating sides (e.g., interior or exterior) or orientation (e.g., clockwise vs. counterclockwise, right handed vs. left handed).

In three-dimensional space, a surface normal, or simply normal, to a surface at point P is a vector perpendicular to the tangent plane of the surface at P. The vector field of normal directions to a surface is known as Gauss map. The word "normal" is also used as an adjective: a line normal to a plane, the normal component of a force, etc. The concept of normality generalizes to orthogonality (right angles).

The concept has been generalized to differentiable manifolds of arbitrary dimension embedded in a Euclidean space. The normal vector space or normal space of a manifold at point is the set of vectors which are orthogonal to the tangent space at Normal vectors are of special interest in the case of smooth curves and smooth surfaces.

The normal is often used in 3D computer graphics (notice the singular, as only one normal will be defined) to determine a surface's orientation toward a light source for flat shading, or the orientation of each of the surface's corners (vertices) to mimic a curved surface with Phong shading.

The foot of a normal at a point of interest Q (analogous to the foot of a perpendicular) can be defined at the point P on the surface where the normal vector contains Q. The normal distance of a point Q to a curve or to a surface is the Euclidean distance between Q and its foot P.

Normal to space curves

[edit]

The normal direction to a space curve is:

where is the radius of curvature (reciprocal curvature); is the tangent vector, in terms of the curve position and arc-length :

Normal to planes and polygons

[edit]

For a convex polygon (such as a triangle), a surface normal can be calculated as the vector cross product of two (non-parallel) edges of the polygon.

For a plane given by the general form plane equation the vector is a normal.

For a plane whose equation is given in parametric form where is a point on the plane and are non-parallel vectors pointing along the plane, a normal to the plane is a vector normal to both and which can be found as the cross product

Normal to general surfaces in 3D space

[edit]

If a (possibly non-flat) surface in 3D space is parameterized by a system of curvilinear coordinates with and real variables, then a normal to S is by definition a normal to a tangent plane, given by the cross product of the partial derivatives

If a surface is given implicitly as the set of points satisfying then a normal at a point on the surface is given by the gradient since the gradient at any point is perpendicular to the level set

For a surface in given as the graph of a function an upward-pointing normal can be found either from the parametrization giving or more simply from its implicit form giving Since a surface does not have a tangent plane at a singular point, it has no well-defined normal at that point: for example, the vertex of a cone. In general, it is possible to define a normal almost everywhere for a surface that is Lipschitz continuous.

Orientation

[edit]

The normal to a (hyper)surface is usually scaled to have unit length, but it does not have a unique direction, since its opposite is also a unit normal. For a surface which is the topological boundary of a set in three dimensions, one can distinguish between two normal orientations, the inward-pointing normal and outer-pointing normal. For an oriented surface, the normal is usually determined by the right-hand rule or its analog in higher dimensions.

If the normal is constructed as the cross product of tangent vectors (as described in the text above), it is a pseudovector.

Transforming normals

[edit]When applying a transform to a surface it is often useful to derive normals for the resulting surface from the original normals.

Specifically, given a 3×3 transformation matrix we can determine the matrix that transforms a vector perpendicular to the tangent plane into a vector perpendicular to the transformed tangent plane by the following logic:

Write n′ as We must find

Choosing such that or will satisfy the above equation, giving a perpendicular to or an perpendicular to as required.

Therefore, one should use the inverse transpose of the linear transformation when transforming surface normals. The inverse transpose is equal to the original matrix if the matrix is orthonormal, that is, purely rotational with no scaling or shearing.

Hypersurfaces in n-dimensional space

[edit]For an -dimensional hyperplane in -dimensional space given by its parametric representation where is a point on the hyperplane and for are linearly independent vectors pointing along the hyperplane, a normal to the hyperplane is any vector in the null space of the matrix meaning . That is, any vector orthogonal to all in-plane vectors is by definition a surface normal. Alternatively, if the hyperplane is defined as the solution set of a single linear equation , then the vector is a normal.

The definition of a normal to a surface in three-dimensional space can be extended to -dimensional hypersurfaces in . A hypersurface may be locally defined implicitly as the set of points satisfying an equation , where is a given scalar function. If is continuously differentiable then the hypersurface is a differentiable manifold in the neighbourhood of the points where the gradient is not zero. At these points a normal vector is given by the gradient:

The normal line is the one-dimensional subspace with basis

A vector that is normal to the space spanned by the linearly independent vectors v1, ..., vr−1 and falls within the r-dimensional space spanned by the linearly independent vectors v1, ..., vr is given by the r-th column of the matrix Λ = V(VTV)−1, where the matrix V = (v1, ..., vr) is the juxtaposition of the r column vectors. (Proof: Λ is V times a matrix so each column of Λ is a linear combination of the columns of V. Furthermore, VTΛ = I, so each column of V other than the last is perpendicular to the last column of Λ.) This formula works even when r is less than the dimension of the Euclidean space n. The formula simplifies to Λ = (VT)−1 when r = n.

Varieties defined by implicit equations in n-dimensional space

[edit]A differential variety defined by implicit equations in the -dimensional space is the set of the common zeros of a finite set of differentiable functions in variables The Jacobian matrix of the variety is the matrix whose -th row is the gradient of By the implicit function theorem, the variety is a manifold in the neighborhood of a point where the Jacobian matrix has rank At such a point the normal vector space is the vector space generated by the values at of the gradient vectors of the

In other words, a variety is defined as the intersection of hypersurfaces, and the normal vector space at a point is the vector space generated by the normal vectors of the hypersurfaces at the point.

The normal (affine) space at a point of the variety is the affine subspace passing through and generated by the normal vector space at

These definitions may be extended verbatim to the points where the variety is not a manifold.

Example

[edit]Let V be the variety defined in the 3-dimensional space by the equations This variety is the union of the -axis and the -axis.

At a point where the rows of the Jacobian matrix are and Thus the normal affine space is the plane of equation Similarly, if the normal plane at is the plane of equation

At the point the rows of the Jacobian matrix are and Thus the normal vector space and the normal affine space have dimension 1 and the normal affine space is the -axis.

Uses

[edit]- Surface normals are useful in defining surface integrals of vector fields.

- Surface normals are commonly used in 3D computer graphics for lighting calculations (see Lambert's cosine law), often adjusted by normal mapping.

- Render layers containing surface normal information may be used in digital compositing to change the apparent lighting of rendered elements.[citation needed]

- In computer vision, the shapes of 3D objects are estimated from surface normals using photometric stereo.[1]

- The normal vector may be obtained as the gradient of the signed distance function.

Normal in geometric optics

[edit]

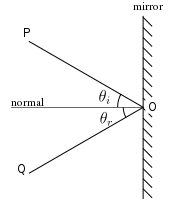

The normal ray is the outward-pointing ray perpendicular to the surface of an optical medium at a given point.[2] In reflection of light, the angle of incidence and the angle of reflection are respectively the angle between the normal and the incident ray (on the plane of incidence) and the angle between the normal and the reflected ray.

See also

[edit]- Dual space – In mathematics, vector space of linear forms

- Ellipsoid normal vector

- Normal bundle – Concept in mathematics

- Pseudovector – Physical quantity that changes sign with improper rotation

- Tangential and normal components – Mathematical vector components

- Vertex normal

- Mean curvature – Differential geometry measure, the average of the signed curvature over all angles

References

[edit]- ^ Ying Wu. "Radiometry, BRDF and Photometric Stereo" (PDF). Northwestern University.

- ^ "The Law of Reflection". The Physics Classroom Tutorial. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Normal Vector". MathWorld.

- An explanation of normal vectors from Microsoft's MSDN

- Clear pseudocode for calculating a surface normal Archived 2016-08-18 at the Wayback Machine from either a triangle or polygon.

Normal (geometry)

View on GrokipediaNormals to Curves

Plane Curves

In plane geometry, the normal to a curve at a given point is defined as the line or vector passing through that point and perpendicular to the tangent line at the same point. This perpendicularity ensures that the normal direction is orthogonal to the curve's instantaneous direction of travel, providing a reference for local orientation and supporting applications in calculus and differential geometry.[5] For a curve represented parametrically as , the tangent vector at parameter is , assuming it is nonzero. A normal vector can then be obtained by rotating by 90 degrees counterclockwise, yielding ; this vector is perpendicular to since their dot product is zero: . The normal line at is the line through the point in the direction of , and may be normalized to unit length by dividing by its magnitude .[5] Curves defined implicitly by an equation , where is differentiable and , have a normal direction given by the gradient vector at any point on the curve. This follows because the gradient is orthogonal to the level set (here ), meaning it is perpendicular to all tangent vectors along the curve; specifically, if is tangent, then by the chain rule applied to . The normal line at a point on the curve is thus parametrized as for scalar .[6] A classic example is the unit circle defined implicitly by . Here, , so the normal direction at any point on the circle is , which coincides with the position vector from the origin and aligns with the radius. This radial normal is perpendicular to the tangent, as the tangent vector at (e.g., ) satisfies .[6][7] The concept of perpendiculars to curves traces back to Euclidean geometry, where such constructions—particularly radii perpendicular to tangents on circles and perpendiculars between lines—formed foundational elements of plane geometry as described in Euclid's Elements around 300 BCE, with the modern term "normal" emerging later to denote these perpendicular directions in English usage by the late 1600s.[8]Space Curves

For a space curve parameterized by arc length in three-dimensional Euclidean space, the unit tangent vector is defined as . The principal normal vector is then given by , provided that the curvature . The magnitude measures the curvature of the curve at , and points in the direction of the principal normal, toward the center of the osculating circle that best approximates the curve locally. This direction aligns with the concavity of the curve in the osculating plane.[9] The principal normal is part of the Frenet frame, which includes the binormal vector and the torsion . The Frenet-Serret formulas describe the derivatives of these vectors with respect to arc length: These equations capture how the frame twists and turns along the curve, with quantifying the rate of rotation out of the osculating plane. A classic example is the circular helix , where and . The speed is , so the arc length parameter is . The unit tangent is , and the principal normal is . For instance, at , , pointing radially inward toward the axis of the helix. The curvature is constant, , and the torsion is .[9] In three dimensions, the principal normal lies in the osculating plane spanned by and at each point, which approximates the curve more closely than any other plane; this contrasts with the normal to a plane curve, where the entire curve lies in the fixed plane containing both the tangent and normal.Normals to Surfaces in Three Dimensions

Planes and Polygons

In three-dimensional Euclidean space, an infinite plane can be defined by the general equation , where , , , and are constants, and not all of , , and are zero. The normal vector to this plane is given by , which is perpendicular to every vector lying within the plane. This normal is unique up to scalar multiplication, meaning any nonzero multiple (for ) also serves as a normal vector./01%3A_Vectors_and_Geometry_in_Two_and_Three_Dimensions/1.04%3A_Equations_of_Planes_in_3d) To obtain a unit normal vector, which has length 1 and is useful for applications requiring normalized directions, divide the normal by its magnitude: , where . This ensures , and there are two possible unit normals pointing in opposite directions.[1] For finite polygonal approximations of surfaces, such as triangles or other polygons in 3D space, the normal vector is computed using the cross product of two non-parallel edge vectors adjacent to a vertex on the polygon. Given edge vectors and from a common vertex, the normal is , which yields a vector perpendicular to the plane of the polygon. Consistent orientation is ensured by adhering to the right-hand rule, where the direction of aligns with the order of and (e.g., counterclockwise when viewed from the side where points outward). For a triangle with vertices , , and , the vectors are and , so . This approach extends to general convex polygons by selecting edges from one vertex or averaging contributions for robustness.[10] A key property of normals to planes and polygons is that they are constant and parallel across all points on the flat surface, unlike the varying normals on curved surfaces. In computational geometry, these are known as facet normals and are essential for tasks like rendering polygonal meshes, collision detection, and surface reconstruction, where they define the local orientation of each face.[11] Historically, the concept of normals to plane faces has roots in crystallography, where early studies of crystal habits in the 17th and 18th centuries used normals to describe the perpendicular directions to planar crystal faces, aiding in the identification of symmetry and morphological relations.[12]Smooth Surfaces

In the context of smooth surfaces in three-dimensional Euclidean space, a normal vector at a point on the surface is perpendicular to the tangent plane at that point. For a parametric representation of a smooth surface given by a vector-valued function , where vary over a domain in the plane, the tangent vectors are the partial derivatives and . These vectors span the tangent plane, and an unnormalized normal vector is obtained by their cross product: .[13][14] Alternatively, a smooth surface can be defined implicitly by a level set , where is a differentiable scalar function. In this case, the normal vector at a point on the surface is the gradient of : . This gradient points in the direction of steepest ascent of , which is orthogonal to the level surface.[15]/16:_Vector_Calculus/16.06:_Parametric_Surfaces_and_Their_Areas) To obtain a unit normal vector, normalize the unnormalized normal by dividing by its magnitude: . For the parametric case, the magnitude represents the area of the parallelogram formed by the tangent vectors, serving as the infinitesimal surface area element in surface integrals.[16]/16:_Vector_Calculus/16.06:_Parametric_Surfaces_and_Their_Areas) A classic example is the unit sphere defined implicitly by . Here, , so , and the unit normal at a point on the surface is . This radial normal aligns with the position vector from the origin.[15] The Gauss map provides a geometric interpretation of normals on a smooth oriented surface, mapping each point on the surface to the unit normal on the unit sphere. This mapping from the surface to the sphere encodes local curvature information; qualitatively, the Gaussian curvature at a point measures how the Gauss map distorts areas, with positive curvature indicating elliptic behavior (like a sphere) and negative indicating hyperbolic (saddle-like).[17]Orientation of Normals

In differential geometry, the orientation of a normal vector to a surface specifies a consistent direction, typically chosen as outward or inward relative to the surface's local geometry. For an orientable surface, this is achieved by selecting a continuous unit normal field that aligns with a right-hand rule convention: the normal points in the direction of the thumb when the fingers curl from one tangent vector to another in the oriented tangent frame. This ensures a coherent "side" across the surface, distinguishing it from the opposite choice, which reverses the direction everywhere.[18][19][20] For closed surfaces, such as a sphere, the outward normal conventionally points away from the interior, facilitating uniform orientation. On a sphere of radius , the position vector normalized by serves as this outward normal, ensuring it radiates from the center. This choice is intrinsic to the surface's topology and supports global consistency without discontinuities. Inward normals, pointing toward the interior, represent the opposite orientation.[21][22] Orientable surfaces, like spheres or planes, allow a consistent normal field defining two distinct sides, whereas non-orientable surfaces, such as the Möbius strip, do not. On a [Möbius strip](/page/Möbius strip), attempting to define a continuous normal field results in the vector flipping direction after traversing the surface once, merging the two sides into one and preventing a global orientation. This topological property underscores the difference between two-sided (orientable) and one-sided (non-orientable) surfaces.[23][24] In advanced contexts, the normal bundle—a line bundle over the surface comprising the orthogonal complement to the tangent space—captures the structure of these normals, while co-orientation refers to an orientation of this bundle via a consistent unit normal field. For a surface embedded in Euclidean space, co-orientation ensures the normal aligns with the ambient metric, enabling properties like curvature to be well-defined. Consider a torus parametrized by angles for the major and minor radii; the normal, derived from the cross product of partial derivatives with respect to these parameters, is chosen to point outward consistently, matching the parametric orientation for a closed, orientable surface.[25][26] The choice of normal orientation has critical implications: in vector calculus, it determines the sign of flux integrals through surfaces, where outward normals measure net outflow (as in the divergence theorem). In computer graphics rendering, consistent outward normals ensure proper lighting and shading by correctly orienting surface facets relative to light sources, avoiding artifacts from inconsistent directions.[27][24]Transforming Normals

In geometry, normal vectors must be transformed carefully under linear mappings to preserve their defining property of perpendicularity to tangent vectors at a point on a surface. Consider a linear transformation represented by an invertible matrix . Tangent vectors in the tangent space transform contravariantly as . To maintain the condition , the normal vector transforms covariantly via the inverse transpose: . This ensures .[28] For affine transformations, which combine linear mappings with translations, normals remain invariant under the translation component since translations do not alter directions or relative orientations. Thus, only the linear part affects the normal, applied as above.[28] Following transformation, the resulting normal may no longer be a unit vector if involves scaling (i.e., if ). In such cases, renormalization is required by dividing by its Euclidean norm to restore unit length, preserving the geometric interpretation.[29] A representative example is a rotation matrix , which is orthogonal (). Here, the inverse transpose coincides with itself, so normals transform identically to tangent vectors, simply rotating without distortion. In contrast, non-uniform scaling, such as a diagonal matrix with unequal , distorts directions unless the inverse transpose (also diagonal with entries ) is applied, which stretches normals inversely to counteract the scaling on tangents.[28] This transformation rule arises from viewing normals as covectors in the dual space to the tangent space. In differential geometry, covectors transform under a change of basis via the inverse of the basis transformation matrix for vectors, reflecting their role in defining hyperplanes through linear functionals (e.g., the zero set of ). In Euclidean space, the standard inner product identifies covectors with vectors, leading to the transpose in the transformation law.[30] In applications such as shading models in computer graphics, surface normals computed in local object space are transformed to world or view coordinates using the inverse transpose of the model matrix to ensure accurate lighting computations.[28]Normals in Higher-Dimensional Spaces

Hypersurfaces

In the context of n-dimensional Euclidean space , a hypersurface is defined as an (n-1)-dimensional submanifold embedded in , which can be realized as the level set of a smooth scalar function where the gradient is nowhere zero on , ensuring is a smooth manifold.[31] The normal to the hypersurface at a point is a vector perpendicular to the tangent hyperplane at , which is the (n-1)-dimensional tangent space . This normal direction spans the one-dimensional orthogonal complement to in the full tangent space .[32] For a hypersurface defined implicitly by , the gradient vector provides a normal vector at each point on the hypersurface, pointing in the direction of the steepest ascent of .[32] The unit normal is then obtained by normalizing: , where is the Euclidean norm, assuming . This unit normal satisfies orthogonality with respect to any tangent vector , meaning , as the level set condition implies that directional derivatives along tangent directions vanish.[32] In higher dimensions, the tangent space is (n-1)-dimensional, and the normal vector spans the 1-dimensional orthogonal complement, providing a unique direction (up to sign) transverse to the hypersurface. For example, consider the hyperplane in defined by , where and ; the normal is , with unit normal .[32] In differential geometry, this construction extends to the normal space at each point, which forms the fibers of the normal bundle over the hypersurface, capturing the transverse geometry.[32]Varieties from Implicit Equations

In algebraic geometry, an affine variety of codimension is defined by the simultaneous vanishing of polynomial equations , where . At a regular point , where the gradients are linearly independent, the normal space is the -dimensional subspace of spanned by these gradients. This normal space is the orthogonal complement to the tangent space , which is the kernel of the Jacobian matrix whose rows are the gradients.[33][34] The rows of the Jacobian matrix directly provide the normal directions, and the rank of equals at regular points, confirming the expected dimension of the normal space. For instance, the surface in defined by has normal space at any point spanned by , consistent with computations for hypersurfaces in three dimensions. At singular points, however, the gradients may vanish or become linearly dependent, causing the rank of the Jacobian to drop below ; this results in a normal space of dimension less than , with the tangent space exceeding its expected dimension .[33][34] A classic example is the nodal cubic curve in given by , which has a singularity at the origin where , rendering the normal space degenerate (zero-dimensional) and the tangent space the entire plane. Unlike treatments assuming smoothness, this approach via implicit equations accommodates such non-manifold singularities, which are intrinsic to algebraic varieties and analyzed through the Jacobian criterion in algebraic geometry.[35][33]Applications of Normals

In Geometric Optics

In geometric optics, the normal to a surface at the point of incidence plays a central role in determining the paths of light rays during reflection and refraction. The normal is defined as the line perpendicular to the tangent plane of the surface at that point, serving as the reference axis for measuring angles. This perpendicularity ensures that the incident ray, the reflected ray (if applicable), and the normal all lie within the same plane, known as the plane of incidence. For smooth surfaces, the normal is computed from the surface's gradient, providing a consistent direction for optical calculations. The law of reflection states that the angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence, with both angles measured from the normal to the surface. If θ_i denotes the angle of incidence between the incident ray and the normal, then the angle of reflection θ_r satisfies θ_r = θ_i. This principle holds for specular reflection on smooth surfaces, such as mirrors, where the normal dictates the direction of the outgoing ray. Mathematically, for unit vectors representing the incident direction i and the surface normal n, the reflected direction r is given by the vector formula: This equation arises from the geometric requirement that the incident and reflected rays make equal angles with the normal while conserving the component parallel to the surface. In a mirror, for instance, the normal at the point of reflection determines the position of specular highlights, where light appears brightest when the observer's line of sight aligns with the reflected ray. The formulation of this law using normals was first rigorously described by René Descartes in his 1637 work La Dioptrique, where he used the normal to derive the equal-angle property from the invariance of the tangential component of the light ray's direction. Refraction, the bending of light at an interface between two media with different refractive indices n_1 and n_2, is governed by Snell's law, which relates the angles of incidence and refraction to the normal. Specifically, n_1 sin θ_i = n_2 sin θ_r, where θ_i is the angle between the incident ray and the normal in the first medium, and θ_r is the corresponding angle for the refracted ray in the second medium. The incident ray, normal, and refracted ray remain coplanar, ensuring the law's application within the plane of incidence. This relationship quantifies how the normal influences the change in direction based on the media's optical densities. An important extension occurs in total internal reflection, when light attempts to refract from a denser medium (n_1 > n_2) to a rarer one and θ_i exceeds the critical angle θ_c = arcsin(n_2 / n_1), such that sin θ_i > n_2 / n_1; in this case, no refraction occurs, and all light reflects internally.In Computer Graphics

In computer graphics, normals play a crucial role in rendering realistic surfaces by determining how light interacts with geometry during shading. Vertex normals, often computed as averages of adjacent polygon facet normals, enable smooth shading across polygonal meshes. These interpolated normals are fundamental to techniques like Gouraud shading, which linearly interpolates colors computed at vertices using facet normals, and Phong shading, which interpolates the normals themselves before per-pixel lighting to achieve smoother highlights.[36][37] Bump mapping perturbs surface normals based on a height field texture to simulate fine geometric details without increasing polygon count, allowing efficient rendering of wrinkled or textured appearances. Introduced by James F. Blinn, this method modifies the shading normal at each pixel by computing partial derivatives of the height function, which are added to the underlying surface normal before normalization.[38] Normal mapping extends bump mapping by directly storing precomputed tangent-space normal perturbations in RGB textures, where the red and green channels encode the X and Y components relative to the surface tangent plane, and blue approximates the Z component. This approach, popularized in real-time rendering, enables high-detail lighting on low-polygon models by transforming the texture normals into world or view space during shading. A seminal implementation demonstrated its robustness on early GPUs, achieving efficient per-pixel lighting for complex surfaces like cloth or skin.[39] To ensure correct lighting under model transformations, vertex and mapped normals must be transformed using the inverse transpose of the model matrix (or model-view matrix), preserving their perpendicularity to the surface even with non-uniform scaling. In shaders, this is typically implemented by computing a 3x3 normal matrix from the upper-left portion of the 4x4 transformation matrix. The following GLSL vertex shader snippet illustrates normal transformation:#version 330 core

uniform mat4 modelViewMatrix;

in vec3 vertexNormal;

out vec3 Normal;

void main() {

mat3 normalMatrix = transpose(inverse(mat3(modelViewMatrix)));

Normal = normalize(normalMatrix * vertexNormal);

// Position transformation omitted for brevity

}

#version 330 core

uniform mat4 modelViewMatrix;

in vec3 vertexNormal;

out vec3 Normal;

void main() {

mat3 normalMatrix = transpose(inverse(mat3(modelViewMatrix)));

Normal = normalize(normalMatrix * vertexNormal);

// Position transformation omitted for brevity

}