Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tangent

View on Wikipedia

In geometry, the tangent line (or simply tangent) to a plane curve at a given point is, intuitively, the straight line that "just touches" the curve at that point. Leibniz defined it as the line through a pair of infinitely close points on the curve.[1][2] More precisely, a straight line is tangent to the curve y = f(x) at a point x = c if the line passes through the point (c, f(c)) on the curve and has slope f'(c), where f' is the derivative of f. A similar definition applies to space curves and curves in n-dimensional Euclidean space.

The point where the tangent line and the curve meet or intersect is called the point of tangency. The tangent line is said to be "going in the same direction" as the curve, and is thus the best straight-line approximation to the curve at that point. The tangent line to a point on a differentiable curve can also be thought of as a tangent line approximation, the graph of the affine function that best approximates the original function at the given point.[3]

Similarly, the tangent plane to a surface at a given point is the plane that "just touches" the surface at that point. The concept of a tangent is one of the most fundamental notions in differential geometry and has been extensively generalized; .

The word "tangent" comes from the Latin tangere, "to touch".

History

[edit]Euclid makes several references to the tangent (ἐφαπτομένη ephaptoménē) to a circle in book III of the Elements (c. 300 BC).[4] In Apollonius' work Conics (c. 225 BC) he defines a tangent as being a line such that no other straight line could fall between it and the curve.[5]

Archimedes (c. 287 – c. 212 BC) found the tangent to an Archimedean spiral by considering the path of a point moving along the curve.[5]

In the 1630s Fermat developed the technique of adequality to calculate tangents and other problems in analysis and used this to calculate tangents to the parabola. The technique of adequality is similar to taking the difference between and and dividing by a power of . Independently Descartes used his method of normals based on the observation that the radius of a circle is always normal to the circle itself.[6]

These methods led to the development of differential calculus in the 17th century. Many people contributed. Roberval discovered a general method of drawing tangents, by considering a curve as described by a moving point whose motion is the resultant of several simpler motions.[7] René-François de Sluse and Johannes Hudde found algebraic algorithms for finding tangents.[8] Further developments included those of John Wallis and Isaac Barrow, leading to the theory of Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz.

An 1828 definition of a tangent was "a right line which touches a curve, but which when produced, does not cut it".[9] This old definition prevents inflection points from having any tangent. It has been dismissed and the modern definitions are equivalent to those of Leibniz, who defined the tangent line as the line through a pair of infinitely close points on the curve; in modern terminology, this is expressed as: the tangent to a curve at a point P on the curve is the limit of the line passing through two points of the curve when these two points tends to P.

Tangent line to a plane curve

[edit]

The intuitive notion that a tangent line "touches" a curve can be made more explicit by considering the sequence of straight lines (secant lines) passing through two points, A and B, those that lie on the function curve. The tangent at A is the limit when point B approximates or tends to A. The existence and uniqueness of the tangent line depends on a certain type of mathematical smoothness, known as "differentiability." For example, if two circular arcs meet at a sharp point (a vertex) then there is no uniquely defined tangent at the vertex because the limit of the progression of secant lines depends on the direction in which "point B" approaches the vertex.

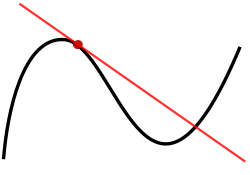

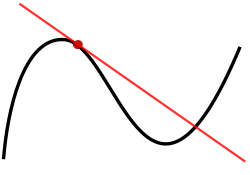

At most points, the tangent touches the curve without crossing it (though it may, when continued, cross the curve at other places away from the point of tangent). A point where the tangent (at this point) crosses the curve is called an inflection point. Circles, parabolas, hyperbolas and ellipses do not have any inflection point, but more complicated curves do have, like the graph of a cubic function, which has exactly one inflection point, or a sinusoid, which has two inflection points per each period of the sine.

Conversely, it may happen that the curve lies entirely on one side of a straight line passing through a point on it, and yet this straight line is not a tangent line. This is the case, for example, for a line passing through the vertex of a triangle and not intersecting it otherwise—where the tangent line does not exist for the reasons explained above. In convex geometry, such lines are called supporting lines.

Analytical approach

[edit]

The geometrical idea of the tangent line as the limit of secant lines serves as the motivation for analytical methods that are used to find tangent lines explicitly. The question of finding the tangent line to a graph, or the tangent line problem, was one of the central questions leading to the development of calculus in the 17th century. In the second book of his Geometry, René Descartes[10] said of the problem of constructing the tangent to a curve, "And I dare say that this is not only the most useful and most general problem in geometry that I know, but even that I have ever desired to know".[11]

Intuitive description

[edit]Suppose that a curve is given as the graph of a function, y = f(x). To find the tangent line at the point p = (a, f(a)), consider another nearby point q = (a + h, f(a + h)) on the curve. The slope of the secant line passing through p and q is equal to the difference quotient

As the point q approaches p, which corresponds to making h smaller and smaller, the difference quotient should approach a certain limiting value k, which is the slope of the tangent line at the point p. If k is known, the equation of the tangent line can be found in the point-slope form:

More rigorous description

[edit]To make the preceding reasoning rigorous, one has to explain what is meant by the difference quotient approaching a certain limiting value k. The precise mathematical formulation was given by Cauchy in the 19th century and is based on the notion of limit. Suppose that the graph does not have a break or a sharp edge at p and it is neither plumb nor too wiggly near p. Then there is a unique value of k such that, as h approaches 0, the difference quotient gets closer and closer to k, and the distance between them becomes negligible compared with the size of h, if h is small enough. This leads to the definition of the slope of the tangent line to the graph as the limit of the difference quotients for the function f. This limit is the derivative of the function f at x = a, denoted f ′(a). Using derivatives, the equation of the tangent line can be stated as follows:

Calculus provides rules for computing the derivatives of functions that are given by formulas, such as the power function, trigonometric functions, exponential function, logarithm, and their various combinations. Thus, equations of the tangents to graphs of all these functions, as well as many others, can be found by the methods of calculus.

How the method can fail

[edit]Calculus also demonstrates that there are functions and points on their graphs for which the limit determining the slope of the tangent line does not exist. For these points the function f is non-differentiable. There are two possible reasons for the method of finding the tangents based on the limits and derivatives to fail: either the geometric tangent exists, but it is a vertical line, which cannot be given in the point-slope form since it does not have a slope, or the graph exhibits one of three behaviors that precludes a geometric tangent.

The graph y = x1/3 illustrates the first possibility: here the difference quotient at a = 0 is equal to h1/3/h = h−2/3, which becomes very large as h approaches 0. This curve has a tangent line at the origin that is vertical.

The graph y = x2/3 illustrates another possibility: this graph has a cusp at the origin. This means that, when h approaches 0, the difference quotient at a = 0 approaches plus or minus infinity depending on the sign of x. Thus both branches of the curve are near to the half vertical line for which y=0, but none is near to the negative part of this line. Basically, there is no tangent at the origin in this case, but in some context one may consider this line as a tangent, and even, in algebraic geometry, as a double tangent.

The graph y = |x| of the absolute value function consists of two straight lines with different slopes joined at the origin. As a point q approaches the origin from the right, the secant line always has slope 1. As a point q approaches the origin from the left, the secant line always has slope −1. Therefore, there is no unique tangent to the graph at the origin. Having two different (but finite) slopes is called a corner.

Finally, since differentiability implies continuity, the contrapositive states discontinuity implies non-differentiability. Any such jump or point discontinuity will have no tangent line. This includes cases where one slope approaches positive infinity while the other approaches negative infinity, leading to an infinite jump discontinuity

Equations

[edit]When the curve is given by y = f(x) then the slope of the tangent is so by the point–slope formula the equation of the tangent line at (X, Y) is

where (x, y) are the coordinates of any point on the tangent line, and where the derivative is evaluated at .[12]

When the curve is given by y = f(x), the tangent line's equation can also be found[13] by using polynomial division to divide by ; if the remainder is denoted by , then the equation of the tangent line is given by

When the equation of the curve is given in the form f(x, y) = 0 then the value of the slope can be found by implicit differentiation, giving

The equation of the tangent line at a point (X,Y) such that f(X,Y) = 0 is then[12]

This equation remains true if

in which case the slope of the tangent is infinite. If, however,

the tangent line is not defined and the point (X,Y) is said to be singular.

For algebraic curves, computations may be simplified somewhat by converting to homogeneous coordinates. Specifically, let the homogeneous equation of the curve be g(x, y, z) = 0 where g is a homogeneous function of degree n. Then, if (X, Y, Z) lies on the curve, Euler's theorem implies It follows that the homogeneous equation of the tangent line is

The equation of the tangent line in Cartesian coordinates can be found by setting z=1 in this equation.[14]

To apply this to algebraic curves, write f(x, y) as

where each ur is the sum of all terms of degree r. The homogeneous equation of the curve is then

Applying the equation above and setting z=1 produces

as the equation of the tangent line.[15] The equation in this form is often simpler to use in practice since no further simplification is needed after it is applied.[14]

If the curve is given parametrically by

then the slope of the tangent is

giving the equation for the tangent line at as[16]

If

the tangent line is not defined. However, it may occur that the tangent line exists and may be computed from an implicit equation of the curve.

Normal line to a curve

[edit]The line perpendicular to the tangent line to a curve at the point of tangency is called the normal line to the curve at that point. The slopes of perpendicular lines have product −1, so if the equation of the curve is y = f(x) then slope of the normal line is

and it follows that the equation of the normal line at (X, Y) is

Similarly, if the equation of the curve has the form f(x, y) = 0 then the equation of the normal line is given by[17]

If the curve is given parametrically by

then the equation of the normal line is[16]

Angle between curves

[edit]The angle between two curves at a point where they intersect is defined as the angle between their tangent lines at that point. More specifically, two curves are said to be tangent at a point if they have the same tangent at a point, and orthogonal if their tangent lines are orthogonal.[18]

Multiple tangents at a point

[edit]

The formulas above fail when the point is a singular point. In this case there may be two or more branches of the curve that pass through the point, each branch having its own tangent line. When the point is the origin, the equations of these lines can be found for algebraic curves by factoring the equation formed by eliminating all but the lowest degree terms from the original equation. Since any point can be made the origin by a change of variables (or by translating the curve) this gives a method for finding the tangent lines at any singular point.

For example, the equation of the limaçon trisectrix shown to the right is

Expanding this and eliminating all but terms of degree 2 gives

which, when factored, becomes

So these are the equations of the two tangent lines through the origin.[19]

When the curve is not self-crossing, the tangent at a reference point may still not be uniquely defined because the curve is not differentiable at that point although it is differentiable elsewhere. In this case the left and right derivatives are defined as the limits of the derivative as the point at which it is evaluated approaches the reference point from respectively the left (lower values) or the right (higher values). For example, the curve y = |x | is not differentiable at x = 0: its left and right derivatives have respective slopes −1 and 1; the tangents at that point with those slopes are called the left and right tangents.[20]

Sometimes the slopes of the left and right tangent lines are equal, so the tangent lines coincide. This is true, for example, for the curve y = x 2/3, for which both the left and right derivatives at x = 0 are infinite; both the left and right tangent lines have equation x = 0.

Tangent line to a space curve

[edit]Tangent circles

[edit]

Two distinct circles lying in the same plane are said to be tangent to each other if they meet at exactly one point.

If points in the plane are described using Cartesian coordinates, then two circles, with radii and centers and are tangent to each other whenever

The two circles are called externally tangent if the distance between their centres is equal to the sum of their radii,

or internally tangent if the distance between their centres is equal to the difference between their radii:[21]

Tangent plane to a surface

[edit]The tangent plane to a surface at a given point p is defined in an analogous way to the tangent line in the case of curves. It is the best approximation of the surface by a plane at p, and can be obtained as the limiting position of the planes passing through 3 distinct points on the surface close to p as these points converge to p. (A technical detail is that the three points must approach p from at least two non-parallel directions. More precisely, two of the three tangent vectors at p must be linearly independent.) Mathematically, if the surface is given by a function , the equation of the tangent plane at point can be expressed as:

Here, and are the partial derivatives of the function with respect to and respectively, evaluated at the point . In essence, the tangent plane captures the local behavior of the surface at the specific point p. It's a fundamental concept used in calculus and differential geometry, crucial for understanding how functions change locally on surfaces.

Higher-dimensional manifolds

[edit]More generally, there is a k-dimensional tangent space at each point of a k-dimensional manifold in the n-dimensional Euclidean space.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ In "Nova Methodus pro Maximis et Minimis" (Acta Eruditorum, Oct. 1684), Leibniz appears to have a notion of tangent lines readily from the start, but later states: "modo teneatur in genere, tangentem invenire esse rectam ducere, quae duo curvae puncta distantiam infinite parvam habentia jungat, seu latus productum polygoni infinitanguli, quod nobis curvae aequivalet", ie. defines the method for drawing tangents through points infinitely close to each other.

- ^ Thomas L. Hankins (1985). Science and the Enlightenment. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780521286190.

- ^ Dan Sloughter (2000) . "Best Affine Approximations"

- ^ Euclid. "Euclid's Elements". Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ a b Shenk, Al. "e-CALCULUS Section 2.8" (PDF). p. 2.8. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ Katz, Victor J. (2008). A History of Mathematics (3rd ed.). Addison Wesley. p. 510. ISBN 978-0321387004.

- ^ Wolfson, Paul R. (2001). "The Crooked Made Straight: Roberval and Newton on Tangents". The American Mathematical Monthly. 108 (3): 206–216. doi:10.2307/2695381. JSTOR 2695381.

- ^ Katz, Victor J. (2008). A History of Mathematics (3rd ed.). Addison Wesley. pp. 512–514. ISBN 978-0321387004.

- ^ Noah Webster, American Dictionary of the English Language (New York: S. Converse, 1828), vol. 2, p. 733, [1]

- ^ Descartes, René (1954) [1637]. The Geometry of René Descartes. Translated by Smith, David Eugene; Latham, Marcia L. Open Court. p. 95.

- ^ R. E. Langer (October 1937). "Rene Descartes". American Mathematical Monthly. 44 (8). Mathematical Association of America: 495–512. doi:10.2307/2301226. JSTOR 2301226.

- ^ a b Edwards Art. 191

- ^ Strickland-Constable, Charles, "A simple method for finding tangents to polynomial graphs", Mathematical Gazette, November 2005, 466–467.

- ^ a b Edwards Art. 192

- ^ Edwards Art. 193

- ^ a b Edwards Art. 196

- ^ Edwards Art. 194

- ^ Edwards Art. 195

- ^ Edwards Art. 197

- ^ Thomas, George B. Jr., and Finney, Ross L. (1979), Calculus and Analytic Geometry, Addison Wesley Publ. Co.: p. 140.

- ^ "Circles For Leaving Certificate Honours Mathematics by Thomas O'Sullivan 1997".

Sources

[edit]- J. Edwards (1892). Differential Calculus. London: MacMillan and Co. pp. 143 ff.

External links

[edit]- "Tangent line", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Tangent Line". MathWorld.

- Tangent to a circle With interactive animation

- Tangent and first derivative — An interactive simulation

Tangent

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Ancient and Medieval Concepts

In ancient Greek geometry, the concept of a tangent was primarily understood as a straight line that touches a curve at exactly one point without crossing it. Euclid, in his Elements (circa 300 BCE), provided an early formal definition in Book III, stating that "a straight line is said to touch a circle which, meeting the circle and being produced, does not cut the circle." This definition emphasized the property of tangency through intersection at a single point, distinguishing it from secant lines that intersect at two points. Euclid further developed these ideas in propositions such as Book III, Proposition 17, which describes the construction of tangents from an external point to a circle using only a ruler and compass: by drawing a line from the external point to the circle's center, constructing a right triangle with the radius perpendicular to the tangent, and ensuring equal lengths of the two tangents from the point. These methods relied on geometric properties like the perpendicularity of the radius to the tangent at the point of contact, as established in Book III, Proposition 16, and exemplified the static, non-infinitesimal notion of tangency prevalent in Greek mathematics. Archimedes, around 250 BCE, extended tangent constructions to more complex curves beyond simple circles. In his treatise On Spirals, he devised geometric methods to draw tangents to the Archimedean spiral at any point, using properties of similar triangles and proportional segments to determine the direction that "touches" the curve without crossing. For parabolas, Archimedes employed his method of exhaustion—not directly for tangent approximation but to rigorously prove areas bounded by parabolic arcs and their tangents—in works like Quadrature of the Parabola, where inscribed triangles approximating the curve converge to the exact area, with tangents defining the boundaries. These approaches highlighted tangents as limiting cases of secants in geometric exhaustion, though without modern limiting processes, focusing instead on finite constructions and inequalities to bound errors. Apollonius of Perga, flourishing around 200 BCE, advanced this further in his influential eight-book treatise Conics, which systematically treated tangents to ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas. He provided geometric constructions for tangents from external points, proved key properties such as the reflection principle for parabolas, and explored asymptotic behavior, laying foundational theory for conic tangents that influenced later mathematics.[5] During the medieval period, Islamic and Indian scholars built upon Greek foundations, applying tangents in optics and algebraic geometry. Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 965–1040 CE), in his Book of Optics, utilized tangents to circles in solving reflection problems, such as determining points on a spherical mirror where incident rays from two points reflect to a third; he constructed auxiliary circles and tangents to verify equal angles of incidence and reflection, as seen in lemmas for Alhazen's problem involving tangent lines at points of tangency to ensure optical paths. In India, Bhāskara II (1114–1185 CE), in his 12th-century text Lilavati, presented practical examples of tangent constructions to circles using right triangles, such as calculating the length of a tangent from an external point via the Pythagorean theorem applied to the right triangle formed by the line from the point to the center, the radius, and the tangent segment. These constructions, often posed as problems solvable with ruler and compass, integrated arithmetic and geometry without invoking infinitesimals, emphasizing empirical verification through triangular dissections. Such geometric conceptions of tangency, rooted in touching without crossing, provided essential groundwork that later evolved into dynamic interpretations in the 17th century.Emergence in Early Calculus

The concept of the tangent began to evolve from geometric intuition to a more analytical framework in the 17th century, building on ancient notions of tangents to circles as lines touching a curve at a single point without crossing it.[6] René Descartes advanced this understanding through his work in algebraic geometry, particularly in La Géométrie (1637), where he developed a method to find tangents to algebraic curves by treating them as slopes derived from coordinate equations.[7] This approach integrated algebra with geometry, allowing tangents to be computed systematically for non-circular curves, marking a shift toward treating curves as loci defined by equations rather than purely geometric figures. Independently, Pierre de Fermat introduced his "adequality" method around the 1630s for determining maxima and minima, which involved comparing algebraic expressions to identify points where tangent slopes indicated stationary values, effectively using infinitesimals to approximate these slopes.[6] Fermat's technique, detailed in letters and treatises from 1636–1642, relied on setting up equations that equated curve ordinates to find tangent directions without explicit limits.[8] By the late 17th century, these ideas culminated in the foundations of calculus, with Isaac Barrow's Geometrical Lectures (1670) presenting tangents as the limiting positions of secant lines to curves, approached through geometric constructions that foreshadowed integral relationships.[9] Barrow's work emphasized visual and infinitesimal arguments to determine tangent lengths and areas, bridging earlier algebraic methods to a more dynamic view of curves.[10] Isaac Newton, in his unpublished De Methodis Serierum et Fluxionum (1671), conceptualized tangents via "fluxions"—instantaneous rates of change of flowing quantities—applying this to solve problems in motion and curve properties, where the tangent represented the direction of a curve's momentary variation.[11] Concurrently, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz developed differential notation in the 1670s, using symbols like dx and dy to denote infinitesimal changes, which allowed tangents to be expressed as ratios of these differentials, facilitating computations for a wide range of curves.[12] Leibniz's approach, outlined in manuscripts from 1675 onward, treated tangents as arising from the geometry of infinitesimally small triangles.[13] The parallel developments by Newton and Leibniz led to a bitter priority controversy in the early 18th century, escalating after 1711 when the Royal Society, under Newton's influence, accused Leibniz of plagiarizing fluxions, despite evidence of independent invention—Newton's work from the 1660s and Leibniz's from the 1670s.[14] This dispute, fueled by national rivalries and personal animosities, divided the mathematical community but ultimately highlighted the shared infinitesimal foundations of their methods for tangents and beyond.[15] These 17th-century innovations laid the groundwork for calculus but relied on intuitive infinitesimals; their transition to rigorous formulations occurred in the 19th century through the limit-based approaches of Augustin-Louis Cauchy and Karl Weierstrass, who eliminated ambiguities by defining continuity and derivatives precisely without infinitesimals.[16]Tangent Lines to Plane Curves

Intuitive and Geometric Definition

In geometry, the tangent line to a plane curve at a given point is the straight line that touches the curve at exactly that point and shares the same instantaneous direction as the curve there, without crossing the curve locally near the point of contact.[1] This concept provides the best linear approximation to the curve in the immediate vicinity of the point, capturing the curve's local behavior visually.[17] For a circle, the tangent line at any point is unique and perpendicular to the radius drawn from the center to that point, ensuring it touches the circle at precisely one location and lies entirely outside the curve otherwise.[18] In contrast, for a general smooth plane curve, the tangent line similarly contacts the curve at the specified point with matching direction, approximating the curve's path so closely that, upon sufficient magnification, the curve appears indistinguishable from the line. This zooming intuition, historically rooted in efforts to understand instantaneous rates along curves, underscores the tangent as the limiting position where the curve straightens locally.[19] Visually, one can conceptualize the tangent by considering secant lines—chords connecting two nearby points on the curve—which approach the tangent as the points coincide; diagrams typically illustrate a sequence of such secants converging to the tangent, highlighting how their slopes and positions stabilize at the point of tangency. For example, on the parabola , the tangent at the point (1, 1) touches the curve there and follows its upward-opening arc without intersecting nearby, providing a straight-line proxy for the curve's gentle bend.[20] Similarly, for an ellipse, the tangent at a point on its boundary aligns with the curve's elongated contour, touching solely at that spot and reflecting the ellipse's varying curvature.[21] For smooth curves, the tangent line is unique at each point, ensuring a well-defined local direction. However, at points of non-smoothness like cusps, the concept can become ambiguous; for instance, the curve features a cusp at the origin where the tangent appears vertical, though some geometric interpretations question its existence due to the sharp turn.[22] This intuitive geometric view aligns with analytical methods, such as limits of secant slopes, for formal confirmation.[23]Analytical Approach Using Limits

The analytical approach to defining the tangent line to a curve formalizes the intuitive geometric idea of a line "touching" the curve at a point by employing the calculus concept of limits, which provides a rigorous measure of the instantaneous rate of change. This method addresses limitations in purely geometric definitions by quantifying the slope through the behavior of secant lines as they approach the point of tangency. For a function that is differentiable at , the slope of the tangent line at the point is given by the limit where denotes the derivative of at .[24] This limit represents the slope of secant lines connecting to nearby points as approaches zero, capturing the precise steepness at the point without relying on visual approximation.[25] Assuming the derivative exists, the equation of the tangent line at follows directly from the point-slope form: This line serves as the best linear approximation to the curve near , with the derivative determining its direction. For example, consider ; the derivative is . At , where and , the tangent line equation is , or . This setup requires prerequisite knowledge of basic functions and the limit concept, which resolves ambiguities in intuitive definitions by ensuring the secant slopes converge to a unique value.[26] However, the limit definition presupposes differentiability at ; if the limit fails to exist or is infinite, no tangent line in the standard sense is defined. Non-differentiability occurs in cases such as corners, where left- and right-hand limits differ—for instance, at , with left derivative and right derivative .[27] Vertical tangents arise when the derivative limit is infinite, as in at , where approaches from both sides, resulting in a vertical line . Cusps, like at , also exhibit infinite derivatives approaching from the same direction, producing a sharp point with a vertical tangent. These failure cases highlight the necessity of the limit's existence for a well-defined tangent slope.[28]Equations and Derivation

For an explicit function , the equation of the tangent line at the point , where , is given by the point-slope form with slope .[29] This slope arises from the limit definition of the derivative, which represents the instantaneous rate of change at , equivalent to the slope of the secant lines approaching the tangent as approaches zero.[24] Rearranging the point-slope equation yields the general linear form , where , , and , providing a normalized representation of the line passing through the point with the given slope.[30] As an illustrative example, consider at . Here, , so and . Substituting into the point-slope form gives , or simply , a horizontal tangent line./03%3A_Topics_in_Differential_Calculus/3.01%3A_Tangent_Lines) For an implicit curve defined by , implicit differentiation yields the slope of the tangent at a point on the curve as provided , where and are the partial derivatives with respect to and , respectively. This follows from differentiating to obtain . The resulting slope can then be substituted into the point-slope form using the point . For a parametric curve , the tangent vector at is , and the slope of the tangent line is if .[31] This ratio derives from the chain rule applied to as a function of via . The point-slope form is then used with the point and this slope. In the special case of a vertical tangent, where and , the tangent line is , a vertical line parallel to the y-axis.[32] In polar coordinates, for a curve , the slope of the tangent line at is obtained by expressing and , then applying the parametric slope formula with .[33] Vertical tangents occur when the denominator is zero and the numerator is nonzero.Normal Lines and Angles Between Curves

The normal line to a curve at a point is the line perpendicular to the tangent line at that point. If the tangent line has slope , the normal line has slope , provided . This perpendicularity follows from the property that the product of the slopes of two perpendicular lines is .[34] To derive the equation of the normal line, start with the equation of the tangent line at a point on the curve , where the tangent slope is . The tangent equation is . The normal line passes through the same point but uses slope , yielding . If , the tangent is horizontal and the normal is vertical, given by .[35] The angle between two curves at their point of intersection is the angle between their tangent lines at that point. If the tangents have slopes and , then assuming (to avoid parallel or undefined cases). This formula arises from the tangent addition formula for the angle between two lines.[36] One application of normal lines and angles is in orthogonal trajectories, which are families of curves that intersect a given family at right angles, meaning their tangents are perpendicular () at every intersection point. To find them, differentiate the original family's equation to obtain a differential equation, replace the slope with its negative reciprocal, and solve the resulting equation. For example, the family of circles (centered at the origin) has orthogonal trajectories consisting of straight lines through the origin, , as the radial lines are perpendicular to the circular tangents everywhere. Geometrically, the normal line at a point on a curve represents the direction perpendicular to the curve's instantaneous direction of travel, which aligns with the principal normal vector in the osculating plane and points toward the center of curvature for smooth curves. In the context of optimization or gradient flows on surfaces defined by curves, this direction corresponds to the steepest ascent orthogonal to the constraint curve./14:_Partial_Differentiation/14.05:_Directional_Derivatives) Consider the parabola at the point . The derivative is , so the tangent slope is . The normal slope is , and the normal equation is , or .[34] For the angle between (slope ) and (slope at ), substitute into the formula: Thus, . This measures the acute angle between the curves at their intersection.[36]Tangent Lines to Space Curves

Parametric Definition

In three-dimensional Euclidean space, a space curve is defined parametrically by a differentiable vector-valued function , where varies over an interval and the component functions , , and are differentiable.[37] The tangent vector to the curve at a point corresponding to parameter value is the derivative , provided .[38] This vector captures both the direction of the curve's instantaneous motion at that point and the speed at which the parametrization traverses the curve, with its magnitude representing the speed.[38] To obtain a direction vector of unit length, the unit tangent vector is defined as .[38] The equation of the tangent line to the space curve at is then given in parametric form by , where is the parameter along the line; equivalently, using the unit tangent, it can be written as ./01:_Vectors_and_Geometry_in_Two_and_Three_Dimensions/1.06:_Curves_and_their_Tangent_Vectors) Geometrically, this line approximates the curve locally near and aligns with the curve's direction of travel, providing the best linear approximation to the curve at that point.[38] If the curve is parametrized by arc length , meaning for all , then the tangent vector coincides with the unit tangent vector , simplifying computations by eliminating the normalization step./01:_Vectors_and_Geometry_in_Two_and_Three_Dimensions/1.06:_Curves_and_their_Tangent_Vectors) For a representative example, consider the helical space curve . Its derivative is , so the unit tangent vector is (since ).[38] At , for instance, the tangent line passes through the point in the direction ./01:_Vectors_and_Geometry_in_Two_and_Three_Dimensions/1.06:_Curves_and_their_Tangent_Vectors) Unlike tangent lines to plane curves, which can be characterized by a single slope, the tangent to a space curve requires a full three-dimensional vector description, as the direction may not lie in a coordinate plane.[31] This vector-based definition generalizes the limit approach for plane curves to higher dimensions.[38] In the context of curve properties, the unit tangent vector serves as the first basis vector in the Frenet frame, an orthonormal moving frame along the curve that also includes principal normal and binormal vectors to describe local geometry.[39]Geometric Properties

The osculating plane at a point on a space curve is the plane spanned by the tangent vector and the principal normal vector at that point.[40] This plane provides the best local approximation to the curve near the point, containing both the tangent line and the direction in which the curve bends instantaneously. The direction of the tangent vector along a space curve changes at a rate governed by the curve's curvature, denoted κ, which quantifies the bending and is given by the formula where is the parametric position vector of the curve.[41] Zero curvature implies no change in tangent direction, while positive curvature indicates deviation from straight-line motion. For a straight line in space, the tangent vector remains constant in direction and magnitude, resulting in zero curvature throughout.[42] In contrast, for a circle embedded in space, the tangent vector at any point is perpendicular to the radius vector from the circle's center to that point, reflecting the uniform curvature of the circle. At singular points on a space curve, such as self-intersections or cusps, multiple distinct tangent directions may exist, forming a tangent cone rather than a unique line.[43] Geometrically, the tangent line to a space curve at a point can be visualized as the limiting position of secant lines connecting two nearby points on the curve as those points approach the given point.[1]Tangent Planes to Surfaces

Definition via Partial Derivatives

In multivariable calculus, the tangent plane to a surface graphed as at a point , where , is the plane that best approximates the surface locally and matches its slopes in the coordinate directions. This plane is defined using the partial derivatives and , which give the rates of change with respect to and , respectively. The equation of the tangent plane is This formulation arises from considering the surface as a level set or extending the single-variable tangent line concept to two dimensions.[3] For surfaces defined implicitly by an equation , where is differentiable and , the gradient vector at the point serves as a normal vector to the tangent plane. The plane equation is then or equivalently, This approach leverages the fact that the gradient is perpendicular to the level surface.[44] Surfaces can also be parameterized by , where vary over a domain. At a point , the tangent plane is the affine plane passing through this point and spanned by the tangent vectors and , assuming these vectors are linearly independent (i.e., ). A normal vector to the plane is the cross product , and the plane equation follows from the normal form.[45] As an example, consider the -plane defined by . Here, , so everywhere, and the tangent plane equation simplifies to , meaning the surface is tangent to itself at every point.[3] For the unit sphere , an implicit surface with , the gradient is . At the point , , yielding the tangent plane equation , or simply .[44] The tangent plane provides a local linear approximation to the surface near the point of tangency. For , the surface value is approximated by , which is the height of the tangent plane above the -plane; this first-order Taylor expansion captures the surface's behavior to linear order. Similar approximations hold for implicit and parametric forms using their respective definitions./14:_Differentiation_of_Functions_of_Several_Variables/14.04:_Tangent_Planes_and_Linear_Approximations)Local Linear Approximation

The local linear approximation provides a first-order estimate of a function near a point , given bywhere and , with the error bounded by as the point approaches . This approximation arises from the requirement that the function is differentiable at the point, ensuring the tangent plane matches the surface's behavior to first order. Geometrically, this corresponds to the graph of the linear function lying in the tangent plane to the surface at .[46][47] In practice, the tangent plane serves as a tool for graphing surfaces, offering a flat, linear representation that simplifies visualization and computation near the reference point. Beyond graphing, the normal vector to the tangent plane—perpendicular to the surface—finds applications in optics, where it determines reflection directions for light rays incident on curved mirrors or lenses under the tangent plane approximation. In computer graphics, this normal facilitates realistic shading models, such as Phong reflection, by computing how light interacts locally with the surface for rendering images.[47][48][49] The differential form captures the projected change in the function value along directions in the tangent plane, providing an infinitesimal approximation for increments in the surface height. This is particularly useful for error estimation in optimization problems, where the tangent plane linearizes constraints or objectives on the surface, aiding gradient-based methods to assess local minima or maxima. For volume estimation under a surface, the tangent plane can approximate the integral over a small region by integrating the constant height from the linear model, yielding a first-order accurate volume bound.[3][46] A concrete example is the paraboloid at the origin , where and , so the local linear approximation simplifies to ; this plane touches the upward-opening bowl at its vertex, accurately estimating values near the origin but diverging quadratically farther away. Another application involves approximating volumes: for a small disk around the origin under this paraboloid, the tangent plane at gives a zero-volume estimate, which serves as a lower bound highlighting the curvature's positive contribution. However, such approximations fail at singular points where the function lacks differentiability, as seen at the apex of the cone , where partial derivatives vanish and no unique tangent plane exists, leading to multiple possible limiting planes without a well-defined linearization.[46][3][3]