Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The Shire

View on Wikipedia

| The Shire | |

|---|---|

| Middle-earth location | |

Part of the Shire created for Peter Jackson's films of Middle-earth, on a farm near Matamata, New Zealand | |

| First appearance | The Hobbit |

| Created by | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Genre | High fantasy |

| In-universe information | |

| Type | Region |

| Ruled by | Thain, Mayor |

| Ethnic groups | Harfoots, Stoors, Fallohides |

| Race | Hobbits |

| Location | Northwest of Middle-earth |

| Characters | |

| Chief township | Michel Delving on the White Downs |

The Shire is a region of J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional Middle-earth, described in The Lord of the Rings and other works. The Shire is an inland area settled exclusively by hobbits, the Shire-folk, largely sheltered from the goings-on in the rest of Middle-earth. It is in the northwest of the continent, in the region of Eriador and the Kingdom of Arnor.

The Shire is the scene of action at the beginning and end of Tolkien's The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Five of the protagonists in these stories have their homeland in the Shire: Bilbo Baggins (the title character of The Hobbit), and four members of the Fellowship of the Ring: Frodo Baggins, Samwise Gamgee, Merry Brandybuck, and Pippin Took. At the end of The Hobbit, Bilbo returns to the Shire, only to find out that he has been declared "missing and presumed dead" and that his hobbit-hole and all its contents are up for auction. (He reclaims them, much to the spite of his cousins Otho and Lobelia Sackville-Baggins.) The main action in The Lord of the Rings returns to the Shire near the end of the book, in "The Scouring of the Shire", when the homebound hobbits find the area under the control of Saruman's ruffians, and set things to rights.

Tolkien based the Shire's landscapes, climate, flora, fauna, and placenames on Worcestershire and Warwickshire, the rural counties in England where he lived. In Peter Jackson's film adaptations of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, the Shire was represented by countryside and constructed hobbit-holes on a farm near Matamata in New Zealand, which became a tourist destination.

Fictional description

[edit]

Tolkien took considerable trouble over the exact details of the Shire. Little of his carefully crafted[1] fictional geography, history, calendar, and constitution appeared in The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings, though additional details were given in the Appendices of later editions. The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey comments that all the same, they provided the "depth", the feeling in the reader's mind that this was a real and complex place, a quality that Tolkien believed essential to a successful fantasy.[2]

Geography

[edit]Four farthings

[edit]In Tolkien's fiction, the Shire is described as a small but beautiful, idyllic and fruitful land, beloved by its hobbit inhabitants. They had agriculture but were not industrialized. The landscape included downland and woods like the English countryside. The Shire was fully inland; most hobbits feared the Sea.[T 1] The Shire measured 40 leagues (193 km, 120 miles)[T 2] east to west and 50 leagues (241 km, 150 miles) from north to south, with an area of some 18,000 square miles (47,000 km2):[T 1][T 3] roughly that of the English Midlands. The main and oldest part of the Shire was bordered to the east by the Brandywine River, on the north by uplands rising to the Hills of Evendim, on the west by the Far Downs, and on the south by marshland. It expanded to the east into Buckland between the Brandywine and the Old Forest, and (much later) to the west into the Westmarch between the Far Downs and the Tower Hills.[T 1][T 4][1]

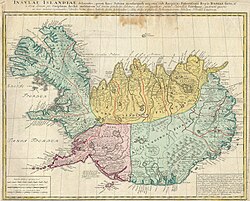

The Shire was subdivided into four Farthings ("fourth-ings", "quarterings"),[T 5] as Iceland once was;[3] similarly, Yorkshire was historically divided into three "ridings".[4] The Three-Farthing Stone marked the approximate centre of the Shire.[T 6] It was inspired by the Four Shire Stone near Moreton-in-Marsh, where once four counties met, but since 1931 only three do.[5][b] There are several Three Shire Stones in England, such as in the Lake District,[7] and formerly some Three Shires Oaks, such as at Whitwell in Derbyshire, each marking the place where three counties once met.[8] Pippin was born in Whitwell in the Tookland.[T 7] Within the Farthings there are unofficial clan homelands: the Tooks nearly all live in or near Tuckborough in Tookland's Green Hill Country.[1][c]

Buckland

[edit]Buckland, also known as the "East Marches", was just to the east of the Shire across the Brandywine River. Named for the Brandybuck family, it was settled "long ago" as "a sort of colony of the Shire." It was bounded to the east by the Old Forest, separated by a tall thick hedge called the High Hay.[10] It included Crickhollow, which serves as one of Frodo's five Homely Houses.[11]

The Westmarch or West Marches was given to the Shire by King Elessar after the War of the Ring.[T 5][T 8]

Bree

[edit]To the east of the Shire was the isolated village of Bree, unique in having hobbits and men living side-by-side. It was served by an inn named The Prancing Pony,[T 9] noted for its fine beer which was sampled by hobbits, men, and the wizard Gandalf.[T 10] Many inhabitants of Bree, including the inn's landlord Barliman Butterbur, had surnames taken from plants. Tolkien described the butterbur as "a fat thick plant", evidently chosen as appropriate for a fat man.[T 11][12] Tolkien suggested two different origins for the people of Bree: either it had been founded and populated by men of the Edain who did not reach Beleriand in the First Age, remaining east of the mountains in Eriador; or they came from the same stock as the Dunlendings.[T 9][T 12] The name Bree means "hill"; Tolkien justified the name by arranging the village and the surrounding Bree-land around a large hill, named Bree-hill. The name of the village Brill, in Buckinghamshire, a place that Tolkien often visited,[T 13][13] and which inspired him to create Bree,[T 13] has the same meaning: Brill is a modern contraction of Breʒ-hyll. Both syllables are words for "hill" – the first is Celtic and the second Old English.[14]

-

The name "Bree" was inspired by the name of the village of Brill, Buckinghamshire; it contains the Celtic Breʒ and the Old English hyll, both meaning "hill".[14]

-

The Bell Inn in Moreton-in-Marsh may have inspired Tolkien to create The Prancing Pony inn at Bree.[15]

History

[edit]The Shire was first settled by hobbits in the year 1601 of the Third Age (Year 1 in Shire Reckoning); they were led by the brothers Marcho and Blanco. The hobbits from the vale of Anduin had migrated west over the perilous Misty Mountains, living in the wilds of Eriador before moving to the Shire.[1]

After the fall of Arnor, the Shire remained a self-governing realm; the Shire-folk chose a Thain to hold the king's powers. The first Thains were the heads of the Oldbuck clan. When the Oldbucks settled Buckland, the position of Thain was peacefully transferred to the Took clan. The Shire was covertly protected by Rangers of the North, who watched the borders and kept out intruders. Generally the only strangers entering the Shire were Dwarves travelling on the Great Road from their mines in the Blue Mountains, and occasional Elves on their way to the Grey Havens. In S.R. 1147 the hobbits defeated an invasion of Orcs at the Battle of Greenfields. In S.R. 1158–60, thousands of hobbits perished in the Long Winter and the famine that followed.[T 14] In the Fell Winter of S.R. 1311–12, white wolves from Forodwaith invaded the Shire across the frozen Brandywine river.

The protagonists of The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, lived at Bag End,[d] a luxurious smial or hobbit-burrow, dug into The Hill on the north side of the town of Hobbiton in the Westfarthing. It was the most comfortable hobbit-dwelling in the town; there were smaller burrows further down The Hill.[e] In S.R. 1341 Bilbo Baggins left the Shire on the quest recounted in The Hobbit. He returned the following year, secretly bearing a magic ring. This turned out to be the One Ring. The Shire was invaded by four Ringwraiths in search of the Ring.[T 10] While Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin were away on the quest to destroy the Ring, the Shire was taken over by Saruman through his underling Lotho Sackville-Baggins. They ran the Shire in a parody of a modern state, complete with armed ruffians, destruction of trees and handsome old buildings, and ugly industrialisation.[T 15]

The Shire was liberated with the help of Frodo and his companions on their return at the Battle of Bywater (the final battle of the War of the Ring).[T 15] The trees of the Shire were restored with soil from Galadriel's garden in Lothlórien (a gift to Sam). The year S.R. 1420 was considered by the inhabitants of the Shire to be the most productive and prosperous year in their history.[T 16]

Language

[edit]

The hobbits of the Shire spoke Middle-earth's Westron or Common Speech. Tolkien however rendered their language as modern English in The Hobbit and in Lord of the Rings, just as he had used Old Norse names for the Dwarves. To resolve this linguistic puzzle, he created the fiction that the languages of parts of Middle-earth were "translated" into different European languages, inventing the language of the Riders of Rohan, Rohirric, to be "translated" again as the Mercian dialect of Old English which he knew well.[18][T 17] This set up a relationship something like ancestry between Rohan and the Shire.[18]

Government

[edit]

The Shire had little in the way of government. The Mayor of the Shire's chief township, Michel Delving, was the chief official and was treated in practice as the Mayor of the Shire.[19] There was a Message Service for post, and the 12 "Shirriffs" (three for each Farthing) of the Watch for police; their chief duties were rounding up stray livestock. These were supplemented by a varying number of "Bounders",[f] an unofficial border force. At the time of The Lord of the Rings, there were many more Bounders than usual, one of the few signs for the hobbits of that troubled time. The heads of major families exerted authority over their own areas.[1]

The Master of Buckland, hereditary head of the Brandybuck clan, ruled Buckland and had some authority over the Marish, just across the Brandywine River.[1]

Similarly, the head of the Took clan, often called "The Took", ruled the ancestral Took dwelling of Great Smials, the village of Tuckborough, and the area of The Tookland.[1] He held the largely ceremonial office of Thain of the Shire.[19]

Calendar

[edit]Tolkien devised the "Shire calendar" or "Shire Reckoning" supposedly used by the Shire's hobbits on Bede's medieval calendar. In his fiction, it was created in Rhovanion hundreds of years before the Shire was founded. When hobbits migrated into Eriador, they took up the Kings' Reckoning, but maintained their old names of the months. In the "King's Reckoning", the year began on the winter solstice. After migrating further to the Shire, the hobbits created the "Shire Reckoning", in which Year 1 corresponded to the foundation of the Shire in the year 1601 of the Third Age by Marcho and Blanco.[1][T 18] The Shire's calendar year has 12 months, each of 30 days. Five non-month days are added to create a 365-day year. The two Yuledays signify the turn of the year, so each year begins on 2 Yule. The Lithedays are the three non-month days at midsummer, 1 Lithe, Mid-year's Day, and 2 Lithe. In leap years (every fourth year except centennial years) an Overlithe day is added after Mid-year's Day. There are seven days in the Shire week. The first day of the week is Sterday and the last is Highday. The Mid-year's Day and, when present, Overlithe have no weekday assignments. This causes every day to have the same weekday designation from year to year, instead of changing as in the Gregorian calendar.[T 18]

For the names of the months, Tolkien reconstructed Anglo-Saxon names, his take on what the English would be if it had not adopted Latin names for the months such as January and March. In The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, the names of months and week-days are given in modern equivalents, so Afteryule is called "January" and Sterday is called "Saturday".[T 18]

| Month number |

Shire Reckoning |

Bede's Anglo- Saxon calendar[21] |

Meaning[22] | Approximate Gregorian dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Yule | 22 December | |||

| 1 | Afteryule | Æfterra Gēola | After Christmas | 23 December to 21 January |

| 2 | Solmath | Sol-mōnaþ | [Offering of] Cakes month | 22 January to 20 February |

| 3 | Rethe | Hrēþ-mōnaþ | The goddess Hretha's month | 21 February to 22 March |

| 4 | Astron | Easter-mōnaþ | Easter month | 23 March to 21 April |

| 5 | Thrimidge | Þrimilce-mōnaþ | Thrice-milking month | 22 April to 21 May |

| 6 | Forelithe | Ǣrra-Līða | Before the Solstice | 22 May to 20 June |

| 1 Lithe | 21 June | |||

| Mid-year's Day | 22 June | |||

| Overlithe | Leap day | |||

| 2 Lithe | 23 June | |||

| 7 | Afterlithe | Æftera Līþa | After the Solstice | 24 June to 23 July |

| 8 | Wedmath | Weod-mōnaþ | Weed Month | 24 July to 22 August |

| 9 | Halimath | Hālig-mōnaþ | Holy [Rites] Month | 23 August to 21 September |

| 10 | Winterfilth | Winterfylleth | Winter Fulfilment | 22 September to 21 October |

| 11 | Blotmath | Blōt-mōnaþ | Blood Month[g] | 22 October to 20 November |

| 12 | Foreyule | Ærra Gēola | Before Christmas | 21 November to 20 December |

| 1 Yule | 21 December |

Inspiration

[edit]

A calque upon England

[edit]Shippey writes that not only is the Shire reminiscent of England: Tolkien carefully constructed the Shire as an element-by-element calque upon England.[23][h]

| Element | The Shire | England |

|---|---|---|

| Origin of people | The Angle between the Rivers Hoarwell (Mitheithel) and the Loudwater (Bruinen) from the East (across Eriador)  |

The Angle between Flensburg Fjord and the Schlei, from the East (across the North Sea), hence the name "England"  |

| Original three tribes | Stoors, Harfoots, Fallohides | Angles, Saxons, Jutes[i] |

| Legendary founders named "horse"[j] |

Marcho and Blanco | Hengest and Horsa |

| Length of civil peace | 272 years from Battle of Greenfields to Battle of Bywater | 270 years from Battle of Sedgemoor to Lord of the Rings |

| Organisation | Mayors, moots, Shirriffs | Like "an old-fashioned and idealised England" |

| Surnames | e.g. Banks, Boffin, Bolger, Bracegirdle, Brandybuck, Brockhouse, Chubb, Cotton, Fairbairns, Grubb, Hayward, Hornblower, Noakes, Proudfoot, Took, Underhill, Whitfoot | All are real English surnames. Tolkien comments e.g. that 'Bracegirdle' is "used in the text, of course, with reference to the hobbit tendency to be fat and so to strain their belts".[T 19] |

| Placenames | e.g. "Nobottle" e.g. "Buckland" |

Nobottle, Northamptonshire Buckland, Oxfordshire |

There are other connections; Tolkien equated the latitude of Hobbiton with that of Oxford (i.e., around 52° N).[T 20] The Shire corresponds roughly to the West Midlands region of England in the remote past, extending to Warwickshire and Worcestershire (where Tolkien grew up),[26][27] forming in Shippey's words a "cultural unit with deep roots in history".[28] The name of the Northamptonshire village of Farthinghoe triggered the idea of dividing the Shire into Farthings.[6] Tolkien said that pipe-weed "flourishes only in warm sheltered places like Longbottom;"[T 1] in the seventeenth century, the Evesham area of Worcestershire was well known for its tobacco.[29]

Homely names

[edit]Tolkien made the Shire feel homely and English in a variety of ways, from names such as Bagshot Row[k] and the Mill to country pubs with familiar names such as "The Green Dragon" in Bywater,[l] "The Ivy Bush" near Hobbiton on the Bywater Road,[m] and "The Golden Perch" in Stock, famous for its fine beer.[32][33][34] Michael Stanton comments in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia that the Shire is based partly on Tolkien's childhood at Sarehole, partly on English village life in general with, in Tolkien's words, "gardens, trees, and unmechanized farmland".[1][T 21] The Shire's largest town, Michel Delving, embodies a philological pun: the name sounds much like that of an English country town, but means "Much Digging" of hobbit-holes, from Old English micel, "great" and delfan, "to dig".[35]

Childhood experience

[edit]The industrialization of the Shire was based on Tolkien's childhood experience of the blighting of the Worcestershire and Warwickshire countryside by the spread of heavy industry as the city of Birmingham grew.[27][T 22] The Tolkien family's relocation from Sarehole to Moseley and Kings Heath in 1901, and then again to Edgbaston in 1902, moved them steadily closer to the industry of central Birmingham.[36] Humphrey Carpenter comments in J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography that the views of Moseley were a sad contrast to the Warwickshire countryside of his youth.[37]

"To have just at the age when imagination is opening out, suddenly find yourself in a quiet Warwickshire village, I think it engenders a particular love of what you might call central Midlands English countryside."[38] – J. R. R. Tolkien, BBC interview with Denys Gueroult, 1964

"The Scouring of the Shire", involving a rebellion of the hobbits and the restoration of the pre-industrial Shire, can be read as containing an element of wish-fulfilment on his part, complete with Merry's magic horn to rouse the inhabitants to action.[39]

Adaptations

[edit]Film

[edit]The Shire makes an appearance in both the 1977 The Hobbit[40] and the 1978 The Lord of the Rings animated films.[41]

In Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings motion picture trilogy, the Shire appeared in both The Fellowship of the Ring and The Return of the King. The Shire scenes were shot at a location near Matamata, New Zealand. Following the shooting, the area was returned to its natural state, but even without the set from the movie the area became a prime tourist location. Because of bad weather, 18 of 37 hobbit-holes could not immediately be bulldozed; before work could restart, they were attracting over 12,000 tourists per year to Ian Alexander's farm, where Hobbiton and Bag End had been situated.[42]

Jackson's Bree is constantly unpleasant and threatening, complete with special effects and the Eye of Sauron when Frodo puts on the Ring.[43] In Ralph Bakshi's animated 1978 adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, Alan Tilvern voiced Bakshi's Butterbur (as "Innkeeper");[44] David Weatherley played Butterbur in Jackson's epic,[45] while James Grout played him in BBC Radio's 1981 serialization of The Lord of the Rings.[46] In the 1991 low-budget Russian adaptation of The Fellowship of the Ring, Khraniteli, Butterbur appears as "Lavr Narkiss", played by Nikolay Burov.[47][48] In Yle's 1993 television miniseries Hobitit, Butterbur ("Viljami Voivalvatti" in Finnish, meaning "Billy Butter") was played by Mikko Kivinen.[49] Bree and Bree-land can be explored in the PC game The Lord of the Rings Online.[50]

Jackson revisited the Shire for his films The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey and The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies. The Shire scenes were shot at the same location.[51]

Games

[edit]In the 2006 real-time strategy game The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle Earth II, the Shire appears as both a level in the evil campaign where the player invades in control of a goblin army, and as a map in the game's multiplayer skirmish mode.[52]

In the 2007 MMORPG The Lord of the Rings Online, the Shire appears almost in its entirety as one of the major regions of the game. The Shire is inhabited by hundreds of non-player characters, and the player can get involved in hundreds of quests. The only portions of the original map by Christopher Tolkien that are missing from the game are some parts of the West Farthing and the majority of the South Farthing. A portion of the North Farthing also falls within the in-game region of Evendim for game play purposes.[53]

In the 2009 action game The Lord of the Rings: Conquest, the Shire appears as one of the game's battlegrounds during the evil campaign, where it is razed by the forces of Mordor.[54]

Games Workshop produced a supplement in 2004 for The Lord of the Rings Strategy Battle Game entitled The Scouring of the Shire. This supplement contained rules for a large number of miniatures that depicted the Shire after the War of the Ring had concluded.[55]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Warwickshire, Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire, and Worcestershire

- ^ Tom Shippey states that the placename Farthinghoe (in Northamptonshire) triggered Tolkien's thoughts on the matter.[6]

- ^ The Green Hill Country around the Tuckborough road may have been named for Green Hill Road near Mosely where Tolkien's grandparents lived.[9]

- ^ "Bag End" was the real name of the Worcestershire home of Tolkien's aunt Jane Neave in Dormston.[16][17]

- ^ Tolkien's visualization of Bag End can be found in his illustrations for The Hobbit. His watercolour The Hill: Hobbiton-across-the Water shows the exterior and the surrounding countryside, whilst The Hall at Bag-End [sic] depicts the interior.

- ^ "Bounder" here means a person who guards a boundary. The term is a pun; in Tolkien's time it also meant a dishonourable fellow.[20]

- ^ i.e. slaughtering of livestock, or Sacrificial Month (cf. Old Norse blót

- ^ For another of Tolkien's calques analysed by Shippey,[24] see The Silmarillion § Themes.

- ^ Shippey comments that both nations have forgotten their origins.[25]

- ^ Old English: hengest, stallion; hors, horse; *marh, horse, cf "mare"; blanca, white horse in Beowulf[23]

- ^ Bagshot is a village in Surrey, and sounds as if it is connected to Baggins and Bag End.

- ^ There was a Green Dragon pub in St Aldate's in Oxford in Tolkien's time.[30]

- ^ There is an Ivy Bush pub on the Hagley Road near where Tolkien lived in Birmingham.[31]

References

[edit]Primary

[edit]- ^ a b c d Tolkien 1954a, Prologue

- ^ Tolkien takes a league to be 3 miles, see Unfinished Tales, The Disaster of the Gladden Fields, Appendix on Númenórean Measure.

- ^ Tolkien 1975, "Farthing", "Shire"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix B and Appendix C.

- ^ a b Tolkien 1954a, "Prologue" : "Of the Ordering of the Shire"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, Map of a part of the Shire.

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 5, ch. 1 "Minas Tirith"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix B

- ^ a b Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 9 "At the Sign of the Prancing Pony"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 2 "The Council of Elrond"

- ^ Tolkien 1975, "Butterbur"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix F

- ^ a b Tolkien 1988, ch. 7, p. 131, note 6. "Bree ... [was] based on Brill ... a place which he knew well".

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix B, "Third Age"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 8 "The Scouring of the Shire"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 9 "The Grey Havens"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix F, On Translation

- ^ a b c Tolkien 1955, "Appendix D: Calendars"

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1967) "Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings". Available in A Tolkien Compass (1975) and in The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion (2005), and online at Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings on Academia.edu.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #294 to C. & D. Plimmer, 8 February 1967

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letters #213 to Deborah Webster, 25 October 1958

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, "Foreword to the Second Edition"

Secondary

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stanton 2013, pp. 607–608.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b "Insvlae Islandiae delineatio". Islandskort. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Mills, A. D. (1993). "Riding, East, North, & West". A Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford University Press. p. 272. ISBN 0192831313.

- ^ "Moreton-in-Marsh Tourist Information and Travel Guide". cotswolds.info. Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ a b Shippey 2005, p. 114.

- ^ "Iconic Lake District Three Shires Stone is toppled". The Westmorland Gazette. 12 August 2017.

- ^ "Whitwell Wood". Cheshire Now. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ Blackham, Robert S. (2012). J.R.R. Tolkien: Inspiring Lives. History Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7524-9097-7.

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 5 "A Conspiracy Unmasked"

- ^ Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. p. 65. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.

- ^ Judd, Walter S.; Judd, Graham A. (2017). Flora of Middle-Earth: Plants of J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium. Oxford University Press. pp. 342–344. ISBN 978-0-19-027631-7.

- ^ Tom Shippey, Tolkien and Iceland: The Philology of Envy Archived 2007-10-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Mills, A. D. (1993). "Brill". A Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford University Press. p. 52. ISBN 0192831313.

- ^ ""The Prancing Pony by Barliman Butterbur"" (PDF). ADCBooks. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "Lord of the Rings inspiration in the archives". Explore the Past (Worcestershire Historic Environment Record). 29 May 2013.

- ^ Morton, Andrew (2009). Tolkien's Bag End. Studley, Warwickshire: Brewin Books. ISBN 978-1-85858-455-3. OCLC 551485018. Morton wrote an account of his findings for the Tolkien Library.

- ^ a b c Shippey 2005, pp. 131–133.

- ^ a b The Fellowship of the Ring, "Prologue", "Of the Ordering of the Shire"

- ^ "bounder". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Frank Merry Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, Oxford University Press, 1971, 97f.; M. P. Nilsson, Primitive Time-Reckoning. A Study in the Origins and Development of the Art of Counting Time among the Primitive and Early Culture Peoples, Lund, 1920; c.f. Stephanie Hollis, Michael Wright, Old English Prose of Secular Learning, Annotated Bibliographies of Old and Middle English literature vol. 4, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 1992, p. 194.

- ^ Bede, [the venerable] (1999). "Chapter 15 – The English months". In Willis, Faith (ed.). Bede: The Reckoning of Time. Liverpool University Press. pp. 53–54.

translated with introduction, notes, and commentary by Faith Willis

- ^ a b c Shippey 2005, pp. 115–118.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Shippey 2005, p. 116.

- ^ "1964 BBC Interview. Interview with JRR Tolkien conducted by Denys Gueroult". Tolkien Gateway. 26 November 1964.

To have just at the age when imagination is opening out, suddenly find yourself in a quiet Warwickshire village, I think it engenders a particular love of what you might call central Midlands English countryside.

- ^ a b Lyons, Matthew (22 September 2017). "Find the inspiration for The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit in the British countryside". BBC Countryfile. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

If the Hobbit holes are in Gloucestershire, the spiritual home of the Shire is to the north-east, in the Warwickshire countryside of Tolkien's childhood as the 19th century folded into the 20th. Tolkien located it specifically in 1897, the year of Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, when he was just five.

- ^ Shippey, Tom. Tolkien and the West Midlands: The Roots of Romance, Lembas Extra (1995), reprinted in Roots and Branches, Walking Tree (2007); map

- ^ Hooker, Mark T. (2009). The Hobbitonian Anthology. Llyfrawr. p. 92. ISBN 978-1448617012.

- ^ Garth, John (2020). Tolkien's Worlds: The Places That Inspired the Writer's Imagination. Quarto Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7112-4127-5.

- ^ "Tolkien-Themed Walk – 1st March 2015". Birmingham Conservation Trust. 13 February 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

We pass the Ivy Bush where old Ham Gamgee held court

- ^ Duriez, Colin (1992). The J.R.R. Tolkien Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide to His Life, Writings, and World of Middle-earth. Baker Book House. pp. 121ff. ISBN 978-0-8010-3014-7.

- ^ Tyler, J. E. A. (1976). The Tolkien Companion. Macmillan. p. 201. ISBN 9780333196335.

- ^ Rateliff, John D. (2009). "A Kind of Elvish Craft': Tolkien as Literary Craftsman". Tolkien Studies. 6. West Virginia University Press: 11ff. doi:10.1353/tks.0.0048. S2CID 170947885.

- ^ Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2005). The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion. HarperCollins. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-00-720907-1.

- ^ "Timeline - Early Life". The Tolkien Society.

- ^ "Tolkien Bibliography: 1977 - Humphrey Carpenter - J.R.R. Tolkien: a biography". The Tolkien Library. p. 25. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

Meanwhile, home life was very different from what he had known at Sarehole. His mother had rented a small house on the main road in the suburb of Moseley, and the view from the windows was a sad contrast to the Warwickshire countryside.

- ^ Drew, Bernard A (2005). 100 Most Popular Genre Fiction Authors - Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 558.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Gilkeson, Austin (17 September 2018). "1977's The Hobbit Showed Us the Future of Pop Culture". TOR. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Langford, Barry (2013) [2007]. "Bakshi, Ralph (1938-)". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 47–49. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Huffstutter, P. J. (24 October 2003). "Not Just a Tolkien Amount". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Croft, Janet Brennan (2005). "Mithril Coats and Tin Ears: 'Anticipation' and 'Flattening' in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings Films". In Croft, Janet Brennan (ed.). Tolkien on Film: Essays on Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings. Mythopoeic Press. p. 68. ISBN 1-887726-09-8.

- ^ "Innkeeper". Behind the Voice Actors. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "David Weatherley". RBA Management. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "Inspector Morse actor James Grout dies at 84". BBC News. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "[Khraniteli] The Fellowship of the Ring (1991-): Full Cast & Crew". IMDb. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Vasilieva, Anna (31 March 2021). ""Хранители" и "Властелин Колец": кто исполнил роли в культовых экранизациях РФ и США" ["Keepers" and "The Lord of the Rings": who played the roles in the cult film adaptations of the Russian Federation and the USA] (in Russian). 5 TV. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Barliman Butterbur". WhatCharacter. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Porter, Jason (22 May 2007). "Lord of the Rings Online: Shadows of Angmar". GameChronicles. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Bray, Adam (21 May 2012). "Hanging out in Hobbiton". CNN. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ Ocampo, Jason (2 March 2006). "Review The Lord of the Rings, The Battle for Middle-earth II Review". Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "The Lord of the Rings Online Vault: The Shire". IGN. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Wolfe, Adam (6 February 2009). "Trophy Guide – The Lord of the Rings: Conquest". Playstation Lifestyle. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "The Scouring of the Shire". Games Workshop. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-261-10275-0.

- Stanton, Michael N. (2013) [2007]. "Shire, The". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 607–608. ISBN 978-0415865111.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1975). "Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings". In Lobdell, Jared (ed.). A Tolkien Compass. Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8754-8303-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1988). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Return of the Shadow. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-49863-7.

The Shire

View on GrokipediaDepicted as a fertile, self-sufficient land of approximately 18,000 square miles, spanning forty leagues from west to east and fifty from north to south, the Shire features rolling hills, rivers such as the Brandywine, and extensive farmlands supporting an agricultural economy centered on pipe-weed, mushrooms, ale, and seven daily meals.[1][1] Its climate mirrors that of rural England—cool but mild winters, warm summers, and ample rainfall—fostering a landscape of hobbit-holes burrowed into earth-sheltered mounds for efficient, comfortable living amid gardens and orchards.[1] Divided administratively into four farthings (North, South, East, and West) with the semi-independent Buckland enclave beyond the Brandywine, the region operates under a decentralized system of thains, mayors, and bounders, emphasizing local customs over centralized authority.[1] Hobbits migrated to the Shire around Third Age 1050–1601, initially as forest-dwellers granted the wooded Eriadorian territory by the Dúnedain King Arnor of Arthedain for settlement, evolving into a sedentary, insular society protected unwittingly by the vigilant Rangers of the North who patrolled its borders.[2] This isolation preserved Hobbit traditions—rooted in Anglo-Saxon rural life, with inspirations from Tolkien's Warwickshire childhood—of hospitality, family lineages like the Bagginses and Tooks, and aversion to machinery or adventure beyond local pipesmoking and alehouses, until external threats intruded during the War of the Ring.[1] Key events defining its narrative role include Bilbo Baggins's unexpected journey in The Hobbit, which unearthed the One Ring, and in The Lord of the Rings, Frodo's quest departure from Bag End, culminating in the Scouring of the Shire, where returning Hobbits mobilized to expel Saruman's industrializing ruffians, restoring order through communal resilience rather than hierarchical command.[1] This episode underscores the Shire's core characteristic: a seemingly idyllic, complacent haven whose underlying vitality—simple virtues of thrift, loyalty, and agrarian self-reliance—enables resistance to corruption, symbolizing Tolkien's ideal of unspoiled provincial England against modern despoilment.[1]

![The name "Bree" was inspired by the name of the village of Brill, Buckinghamshire; it contains the Celtic Breʒ and the Old English hyll, both meaning "hill".[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c5/Brill_village_from_Brill_Common_-_geograph.org.uk_-_538330.jpg/500px-Brill_village_from_Brill_Common_-_geograph.org.uk_-_538330.jpg)

![The Bell Inn in Moreton-in-Marsh may have inspired Tolkien to create The Prancing Pony inn at Bree.[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2d/Bell_Inn_Moreton_in_Marsh_back_in_time.jpg/250px-Bell_Inn_Moreton_in_Marsh_back_in_time.jpg)