Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

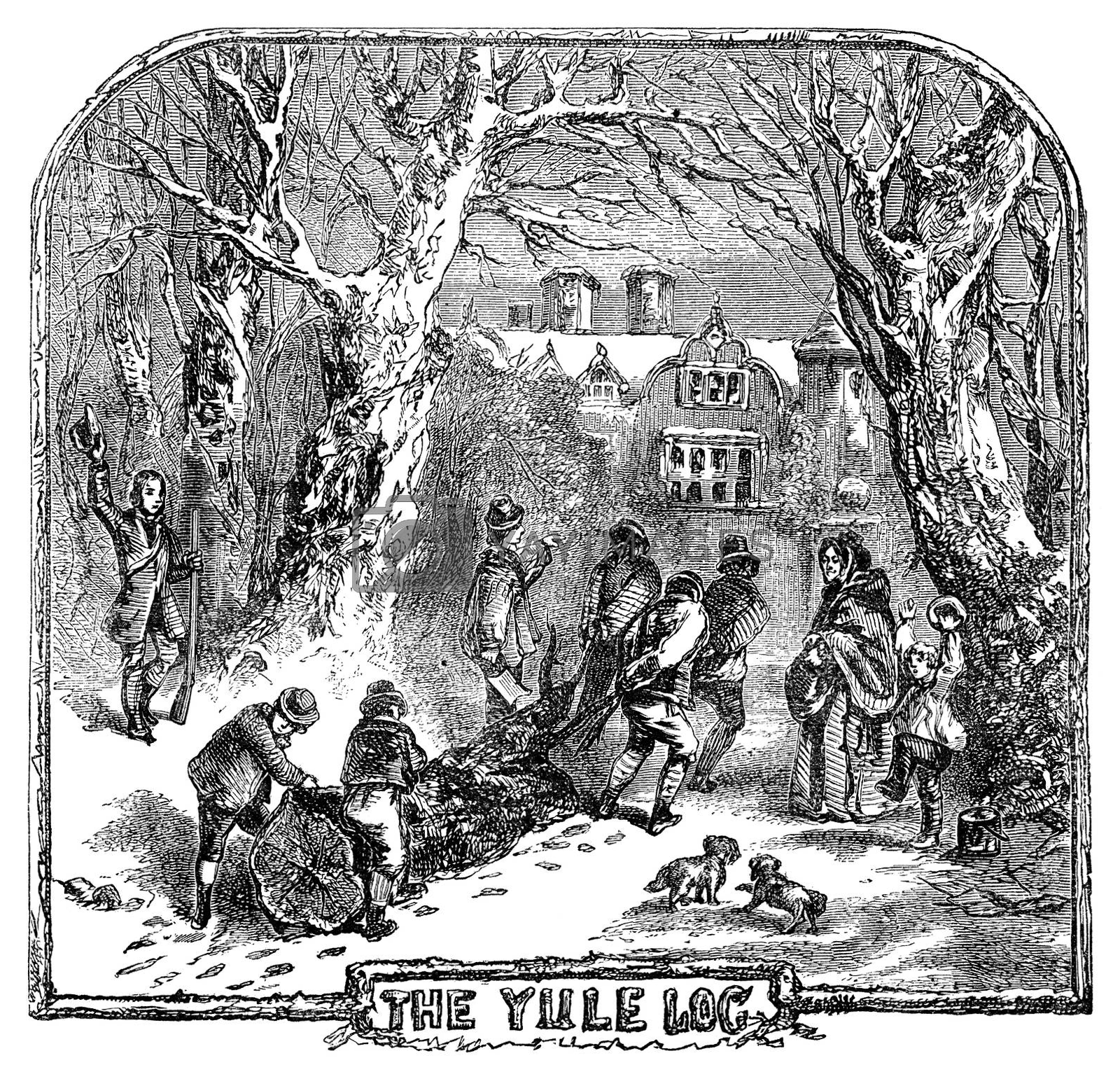

| Yule | |

|---|---|

Hauling a Yule log in 1832 | |

| Also called | Yuletide, Yulefest |

| Observed by | Various Northern Europeans, Germanic peoples, Heathens, Wiccans, Neopagans, LaVeyan Satanists |

| Type | Cultural, Germanic pagan, modern pagan |

| Significance | Winter festival |

| Date | See § Date of observance |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Midwinter, Christmastide, Christmas |

Yule is a winter festival historically observed by the Germanic peoples that was merged with Christmas during the Christianisation of the Germanic peoples. In present times adherents of some new religious movements (such as Modern Germanic paganism) celebrate Yule independently of the Christian festival. Scholars have connected the original celebrations of Yule to the Wild Hunt, the god Odin, and the heathen Anglo-Saxon Mōdraniht ("Mothers' Night"). The term Yule and cognates are still used in English and the Scandinavian languages as well as in Finnish and Estonian to describe Christmas and other festivals occurring during the winter holiday season. Furthermore, some present-day Christmas customs and traditions such as the Yule log, Yule goat, Yule boar, Yule singing, and others may have connections to older pagan Yule traditions.

Etymology

[edit]The modern English noun Yule descends from Old English ġēol, earlier geoh(h)ol, geh(h)ol, and geóla, sometimes plural.[1] The Old English ġēol or ġēohol and ġēola or ġēoli indicate the 12-day festival of "Yule" (later: "Christmastide"), the latter indicating the month of "Yule", whereby ǣrra ġēola referred to the period before the Yule festival (December) and æftera ġēola referred to the period after Yule (January). Both words are cognate with Gothic 𐌾𐌹𐌿𐌻𐌴𐌹𐍃 (jiuleis); Old Norse, Icelandic, Faroese and Norwegian Nynorsk jól, jol, ýlir; Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian Bokmål jul, and are thought to be derived from Proto-Germanic *jehwlą-.[2][3] Whether the term existed exterior to the Germanic languages remains uncertain, though numerous speculative attempts have been made to find Indo-European cognates outside the Germanic group, too.[a] The compound noun Yuletide ('Yule-time') is first attested from around 1475.[4]

The word is applied in an explicitly pre-Christian context primarily in Old Norse, where it is associated with Old Norse deities. Among many others (see List of names of Odin), the god Odin bears the name Jólnir ('the Yule one'). In Ágrip, composed in the 12th century, jól is interpreted as coming from one of Odin's names, Jólnir, closely related to Old Norse jólnar, a poetic name for the gods. In Old Norse poetry, the word is found as a term for 'feast', e.g. hugins jól (→ 'a raven's feast').[5]

It has been thought that Old French jolif (→ French joli), which was borrowed into English in the 14th century as 'jolly', is itself borrowed from Old Norse jól (with the Old French suffix -if; compare Old French aisif "easy", Modern French festif = fest "feast" + -if), according to the Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology[6] and several other French dictionaries of etymology.[7][8] But the Oxford English Dictionary sees this explanation for jolif as unlikely.[9] The French word is first attested in the Anglo-Norman Estoire des Engleis, or "History of the English People", written by Geoffrey Gaimar between 1136 and 1140.[8]

Germanic paganism

[edit]Attestations

[edit]Months, heiti and kennings

[edit]

Yule is attested early in the history of the Germanic peoples; in a Gothic language calendar of the 5–6th century CE it appears in the month name fruma jiuleis, and, in the 8th century, the English historian Bede wrote that the Anglo-Saxon calendar included the months geola or giuli corresponding to either modern December or December and January.[10]

While the Old Norse month name ýlir is similarly attested, the Old Norse corpus also contains numerous references to an event by the Old Norse form of the name, jól. In chapter 55 of the Prose Edda book Skáldskaparmál, different names for the gods are given; one is "Yule-beings" (Old Norse: jólnar). A work by the skald Eyvindr skáldaspillir that uses the term is then quoted: "again we have produced Yule-being's feast [mead of poetry], our rulers' eulogy, like a bridge of masonry".[11] In addition, one of the numerous names of Odin is Jólnir, referring to the event.[12]

Heitstrenging

[edit]Both Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar and Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks provide accounts of the custom of heitstrenging. In these sources, the tradition takes place on Yule-evening and consists of people placing their hands on a pig referred to as a sonargöltr before swearing solemn oaths. In the latter text, some manuscripts explicitly refer to the pig as holy, that it was devoted to Freyr and that after the oath-swearing it was sacrificed.[13]

Saga of Hákon the Good

[edit]The Saga of Hákon the Good credits King Haakon I of Norway who ruled from 934 to 961 with the Christianization of Norway as well as rescheduling Yule to coincide with Christian celebrations held at the time. The saga says that when Haakon arrived in Norway he was a confirmed Christian, but since the land was still altogether heathen and the people retained their pagan practices, Haakon hid his Christianity to receive the help of the "great chieftains". In time, Haakon had a law passed establishing that Yule celebrations were to take place at the same time as the Christians celebrated Christmas, "and at that time everyone was to have ale for the celebration with a measure of grain, or else pay fines, and had to keep the holiday while the ale lasted".[14]

Haakon planned that when he had solidly established himself and held power over the whole country, he would then "have the gospel preached". According to the saga, the result was that his popularity caused many to allow themselves to be baptized, and some people stopped making sacrifices. Haakon spent most of this time in Trondheim. When Haakon believed that he wielded enough power, he requested a bishop and other priests from England, and they came to Norway. On their arrival, "Haakon made it known that he would have the gospel preached in the whole country." The saga continues, describing the different reactions of various regional things.[14]

A description of heathen Yule practices is provided (notes are Hollander's own):

| Old Norse text[15] | Hollander translation[16] |

|---|---|

| Þat var forn siðr, þá er blót skyldi vera, at allir bœndr skyldu þar koma sem hof var ok flytja þannug föng sín, þau er þeir skyldu hafa, meðan veizlan stóð. At veizlu þeirri skyldu allir menn öl eiga; þar var ok drepinn allskonar smali ok svá hross; en blóð þat alt, er þar kom af, þá var kallat hlaut, ok hlautbollar þat, er blóð þat stóð í, ok hlautteinar, þat var svá gert sem stöklar; með því skyldi rjóða stallana öllu saman, ok svá veggi hofsins utan ok innan, ok svá stökkva á mennina; en slátr skyldi sjóða til mannfagnaðar. Eldar skyldu vera á miðju gólfi í hofinu ok þar katlar yfir; ok skyldi full um eld bera. En sá er gerði veizluna ok höfðingi var, þá skyldi hann signa fullit ok allan blótmatinn. | It was ancient custom that when sacrifice was to be made, all farmers were to come to the heathen temple and bring along with them the food they needed while the feast lasted. At this feast all were to take part of the drinking of ale. Also all kinds of livestock were killed in connection with it, horses also; and all the blood from them was called hlaut [sacrificial blood], and hlautbolli, the vessel holding the blood; and hlautteinar, the sacrificial twigs [aspergills]. These were fashioned like sprinklers, and with them were to be smeared all over with blood the pedestals of the idols and also the walls of the temple within and without; and likewise the men present were to be sprinkled with blood. But the meat of the animals was to be boiled and served as food at the banquet. Fires were to be lighted in the middle of the temple floor, and kettles hung over the fires. The sacrificial beaker was to be borne around the fire, and he who made the feast and was chieftain, was to bless the beaker as well as all the sacrificial meat. |

The narrative continues that toasts were to be drunk. The first toast was to be drunk to Odin "for victory and power to the king", the second to the gods Njörðr and Freyr "for good harvests and for peace", and third, a beaker was to be drunk to the king himself. In addition, toasts were drunk to the memory of departed kinsfolk. These were called minni.[16]

Academic reception

[edit]Significance and connection to other events

[edit]Scholar Rudolf Simek says the pagan Yule feast "had a pronounced religious character" and that "it is uncertain whether the Germanic Yule feast still had a function in the cult of the dead and in the veneration of the ancestors, a function which the mid-winter sacrifice certainly held for the West European Stone and Bronze Ages." The traditions of the Yule log, Yule goat, Yule boar Sonargöltr, Yule singing, and others possibly have connections to pre-Christian Yule customs, which Simek says "indicates the significance of the feast in pre-Christian times."[17]

Scholars have connected the month event and Yule period to the Wild Hunt (a ghostly procession in the winter sky), the god Odin (who is attested in Germanic areas as leading the Wild Hunt and bears the name Jólnir), and increased supernatural activity, such as the Wild Hunt and the increased activities of draugar—undead beings who walk the earth.[18]

Mōdraniht, an event focused on collective female beings attested by Bede as having occurred among the heathen Anglo-Saxons when Christians celebrated Christmas Eve, has been seen as further evidence of a fertility event during the Yule period.[19]

Date of observance

[edit]The exact dating of the pre-Christian Yule celebrations is unclear and debated among scholars. Snorri in Hákonar saga góða describes how the three-day feast began on "Midwinter Night", however this is distinct from the winter solstice, occurring approximately one month later. Andreas Nordberg proposes that Yule was celebrated on the full moon of the second Yule month in the Early Germanic calendar (the month that started on the first new moon after the winter solstice), which could range from 5 January to 2 February in the Gregorian calendar. Nordberg positions the Midwinter Nights from 19 to 21 January in the Gregorian calendar, falling roughly in the middle of Nordberg's range of Yule dates. In addition to Snorri's account, Nordberg's dating is also consistent with the account of the great blót at Lejre by Thietmar of Merseburg.[20]

Contemporary traditions

[edit]Relationship with Christmas in Northern Europe

[edit]In modern Germanic language-speaking areas and some other Northern European countries, yule and its cognates denote the Christmas holiday season. In addition to yule and yuletide in English,[21] examples include jul in Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, jól in Iceland and the Faroe Islands, joulu in Finland, Joelfest in Friesland, Joelfeest in the Netherlands and jõulud in Estonia.[citation needed]

Modern paganism

[edit]As contemporary pagan religions differ in both origin and practice, these representations of Yule can vary considerably despite the shared name. Some Heathens, for example, celebrate in a way as close as possible to how they believe ancient Germanic pagans observed the tradition, while others observe the holiday with rituals "assembled from different sources".[22] Heathen celebrations of Yule can also include sharing a meal and gift-giving.[citation needed]

In most forms of Wicca, this holiday is celebrated at the winter solstice as the rebirth of the Great horned hunter god,[23] who is viewed as the newborn solstice sun. The method of gathering for this sabbat varies by practitioner. Some have private ceremonies at home,[24] while others do so with their covens:

Generally meeting in covens, which anoint their own priests and priestesses, Wiccans chant and cast or draw circles to invoke their deities, mainly during festivals like Samhain and Yule, which coincide with Halloween and Christmas, and when the moon is full.[25]

LaVeyan Satanism

[edit]Some members of the Church of Satan and other LaVeyan Satanist groups celebrate Yule at the same time as the Christian holiday in a secular manner.[26]

See also

[edit]- Dísablót, an event attested from Old Norse sources as having occurred among the pagan Norse

- Julebord, the modern Scandinavian Christmas feast

- Koliada, a Slavic winter festival

- Lohri, a Punjabi winter solstice festival

- Saturnalia, an ancient Roman winter festival in honour of the deity Saturn

- Yaldā Night, an Iranian festival celebrated on the "longest and darkest night of the year".

- Nardoqan, the birth of the sun, is an ancient Turkic festival that celebrates the winter solstice.

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For a brief overview of the proposed etymologies, see Orel (2003:205).

Citations

[edit]- ^ OED Online (2022).

- ^ Bosworth & Toller (1898:424); Hoad (1996:550); Orel (2003:205).

- ^ "jol". Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Barnhart (1995:896).

- ^ Vigfússon (1874:326).

- ^ Hoad (1993)

- ^ Dictionnaire historique de la langue française (sous la direction d'Alain Rey), édition Le Robert, t. 2, 2012, p. 1805ab

- ^ a b "JOLI : Etymologie de JOLI". www.cnrtl.fr. Archived from the original on 24 August 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ "jolly, adj. and adv. Archived 16 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine" OED Online, Oxford University Press, December 2019. Accessed 9 December 2019.

- ^ Simek (2007:379).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:133).

- ^ Simek (2007:180–181).

- ^ Kovářová (2011:195–196).

- ^ a b Hollander (2007:106).

- ^ "Saga Hákonar góða – heimskringla.no". heimskringla.no. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ a b Hollander (2007:107).

- ^ Simek (2007:379–380).

- ^ Simek (2007:180–181, 379–380) and Orchard (1997:187).

- ^ Orchard (1997:187).

- ^ Nordberg, Andreas (2006). "Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning". Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi. 91: 155–156. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ OED Online (2022).

- ^ Hutton (2008).

- ^ Buescher (2007).

- ^ Kannapell (1997).

- ^ La Ferla (2000).

- ^ Escobedo (2015).

Works cited

[edit]- Barnhart, Robert K. (1995). The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology. HarperCollins. ISBN 0062700847.

- Bosworth, Joseph; Toller, T. Northcote (1898). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buescher, James (15 December 2007). "Wiccans, pagans ready to celebrate Yule". Lancaster Online. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- Escobedo, Tricia (11 December 2015). "5 things you didn't know about Satanists". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 March 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

So for the Yule holiday season we enjoy the richness of life and the company of people whom we cherish, as we will often be the only ones who know where the traditions really came from!

- Faulkes, Anthony, ed. (1995). Edda. Translated by Anthony Faulkes. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3.

- Hoad, T. F. (1993). English Etymology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283098-8.

- Hoad, T. F. (1996). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283098-8.

- Hollander, Lee M., ed. (2007). Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway. Translated by Lee M. Hollander. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-73061-8.

- Hutton, Ronald (December 2008). "Modern Pagan Festivals: A Study in the Nature of Tradition". Folklore. 119 (3). Taylor & Francis: 251–273. doi:10.1080/00155870802352178. JSTOR 40646468. S2CID 145003549.

- Kannapell, Andrea (21 December 1997). "Celebrations; It's Solstice, Hanukkah, Kwannza: Let There Be Light!". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- Kovářová, Lenka (2011). The Swine in Old Nordic Religion and Worldview. S2CID 154250096.

- La Ferla, Ruth (13 December 2000). "Like Magic, Witchcraft Charms Teenagers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- OED Online (December 2022). "yule, n.". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2.

- Orel, Vladimir (2003). A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 205. ISBN 90-04-12875-1.

- Simek, Rudolf (2007). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Angela Hall. D. S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-513-7.

- Vigfússon, Guðbrandur (1874). An Icelandic-English Dictionary: Based on the Ms. Collections of the Late Richard Cleasby. Clarendon Press. OCLC 1077900672.

External links

[edit]Yule, known in Old Norse as jól, is a Germanic/Norse midwinter festival observed around the winter solstice (December 21–23), marking the sun's rebirth, by Norse and other northern European peoples, featuring communal feasting, ritual animal sacrifices known as blót, and symbolic practices to ensure the sun's return and communal prosperity.[1][2][3] The term derives from the Proto-Germanic root jehwlą, reconstructed as denoting a period of festivity or the midwinter season itself, with cognates appearing in Old English ġēol and Gothic calendars as early as the 4th century.[4][5] Historical attestations, including mentions in Norse sagas and the Prose Edda, describe jól as lasting several nights—often three or up to twelve—with customs such as toasting to fertility, peace, and victory (til árs ok friðar), though primary pre-Christian sources are limited and many details emerge from medieval Christian-era texts.[6][7] A defining ritual involved burning a massive Yule log, typically from oak or ash, over multiple days to ward off darkness, with its ashes spread for agricultural blessing, a practice echoed in later European Christmas traditions.[1] During Christianization, Yule customs were syncretized with Christmas, influencing terms like "Yuletide" and elements such as evergreen decorations and wassailing, while retaining pagan undertones in Scandinavian jul celebrations.[8]