Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Open access

View on Wikipedia

Open access (OA) is a set of principles and a range of practices through which nominally copyrightable publications are delivered to readers free of access charges or other barriers.[1] With open access strictly defined (according to the 2001 definition), or libre open access, barriers to copying or reuse are also reduced or removed by applying an open license for copyright, which regulates post-publication uses of the work.[1]

The main focus of the open access movement has been on "peer reviewed research literature", and more specifically on academic journals.[2] This is because:

- such publications have been a subject of serials crisis, unlike newspapers, magazines and fiction writing. The main difference between these two groups is in demand elasticity: whereas an English literature curriculum can substitute Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone with a public domain alternative, such as A Voyage to Lilliput, an emergency room physician treating a patient for a life-threatening urushiol poisoning cannot substitute the most recent, but paywalled review article on this topic[3] with a 90-year-old copyright-expired article[4] that was published before the invention of prednisone in 1954.

- the authors of research papers are not paid in any way, so they do not suffer any monetary losses, when they switch from behind paywall to open access publishing, especially, if they use diamond open access media.

- the cost of electronic publishing, which has been the main form of distribution of journal articles since c. 2000, is incommensurably smaller than the cost of on-paper publishing and distribution, which is still preferred by many readers of fiction.

Whereas non-open access journals cover publishing costs through access tolls such as subscriptions, site licenses or pay-per-view charges, open-access journals are characterised by funding models which do not require the reader to pay to read the journal's contents, relying instead on author fees or on public funding, subsidies and sponsorships. Open access can be applied to all forms of published research output, including peer-reviewed and non peer-reviewed academic journal articles, conference papers, theses,[5] book chapters,[1] monographs,[6] research reports and images.[7]

Definitions

[edit]There are different models of open access publishing and publishers may use one or more of these models.

Colour naming system

[edit]Different open access types are currently commonly described using a colour system. The most commonly recognised names are "green", "gold", and "hybrid" open access; however, several other models and alternative terms are also used.[8]

Gold OA

[edit]In the gold OA model, the publisher makes all articles and related content available for free immediately on the journal's website. In such publications, articles are licensed for sharing and reuse via Creative Commons licenses or similar.[1]

Many gold OA publishers charge an article processing charge (APC), which is typically paid through institutional or grant funding. The majority of gold open access journals charging APCs follow an "author-pays" model,[13] although this is not an intrinsic property of gold OA.[14]

Green OA

[edit]Self-archiving by authors is permitted under green OA. Independently from publication by a publisher, the author also posts the work to a website controlled by the author, the research institution that funded or hosted the work, or to an independent central open repository, where people can download the work without paying.[15]

Green OA is free of charge for the author. Some publishers (less than 5% and decreasing as of 2014) may charge a fee for an additional service[15] such as a free license on the publisher-authored copyrightable portions of the printed version of an article.[16]

If the author posts the near-final version of their work after peer review by a journal, the archived version is called a "postprint". This can be the accepted manuscript as returned by the journal to the author after successful peer review.[17]

Hybrid OA

[edit]Hybrid open-access journals contain a mixture of open access articles and closed access articles.[18][19] A publisher following this model is partially funded by subscriptions, and only provide open access for those individual articles for which the authors (or research sponsor) pay a publication fee.[20] Hybrid OA generally costs more than gold OA and can offer a lower quality of service.[21] A particularly controversial practice in hybrid open access journals is "double dipping", where both authors and subscribers are charged.[22] For these reasons, hybrid open access journals have been called a "Mephistophelian invention",[23] and publishing in hybrid OA journals often do not qualify for funding under open access mandates, as libraries already pay for subscriptions thus have no financial incentive to fund open access articles in such journals.[24]

Bronze OA

[edit]Bronze open access articles are free to read only on the publisher page, but lack a clearly identifiable license.[25] Such articles are typically not available for reuse.

Diamond/platinum OA

[edit]Journals that publish open access without charging authors article processing charges are sometimes referred to as diamond[26][27][28] or platinum[29][30] OA. Since they do not charge either readers or authors directly, such publishers often require funding from external sources such as the sale of advertisements, academic institutions, learned societies, philanthropists or government grants.[31][32][33] There are now over 350 platinum OA journals with impact factors over a wide variety of academic disciplines, giving most academics options for OA with no APCs.[34] Diamond OA journals are available for most disciplines, and are usually small (<25 articles per year) and more likely to be multilingual (38%); thousands of such journals exist.[28]

Black OA

[edit]

The growth of unauthorized digital copying by large-scale copyright infringement has enabled free access to paywalled literature.[36][37] This has been done via existing social media sites (e.g. the #ICanHazPDF hashtag) as well as dedicated sites (e.g. Sci-Hub).[36] In some ways this is a large-scale technical implementation of pre-existing practice, whereby those with access to paywalled literature would share copies with their contacts.[38][39][40][41] However, the increased ease and scale from 2010 onwards have changed how many people treat subscription publications.[42]

Gratis and libre

[edit]Similar to the free content definition, the terms 'gratis' and 'libre' were used in the Budapest Open Access Initiative definition to distinguish between free to read versus free to reuse.[43]

Gratis open access (![]() ) refers to free online access, to read, free of charge, without re-use rights.[43]

) refers to free online access, to read, free of charge, without re-use rights.[43]

Libre open access (![]() ) also refers to free online access, to read, free of charge, plus some additional re-use rights,[43] covering the kinds of open access defined in the Budapest Open Access Initiative, the Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing and the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities. The re-use rights of libre OA are often specified by various specific Creative Commons licenses;[44] all of which require as a minimum attribution of authorship to the original authors.[43][45] In 2012, the number of works under libre open access was considered to have been rapidly increasing for a few years, though most open-access mandates did not enforce any copyright license and it was difficult to publish libre gold OA in legacy journals.[2] However, there are no costs nor restrictions for green libre OA as preprints can be freely self-deposited with a free license, and most open-access repositories use Creative Commons licenses to allow reuse.[46] The biggest drawback of many Open Access licenses is a prohibition on data mining. For this reason, many big data studies of various technologies performed by economists ( as well as machine learning by computer scientists) are limited to patent analysis, since the patent documents are not subject to copyright at all.

) also refers to free online access, to read, free of charge, plus some additional re-use rights,[43] covering the kinds of open access defined in the Budapest Open Access Initiative, the Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing and the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities. The re-use rights of libre OA are often specified by various specific Creative Commons licenses;[44] all of which require as a minimum attribution of authorship to the original authors.[43][45] In 2012, the number of works under libre open access was considered to have been rapidly increasing for a few years, though most open-access mandates did not enforce any copyright license and it was difficult to publish libre gold OA in legacy journals.[2] However, there are no costs nor restrictions for green libre OA as preprints can be freely self-deposited with a free license, and most open-access repositories use Creative Commons licenses to allow reuse.[46] The biggest drawback of many Open Access licenses is a prohibition on data mining. For this reason, many big data studies of various technologies performed by economists ( as well as machine learning by computer scientists) are limited to patent analysis, since the patent documents are not subject to copyright at all.

FAIR

[edit]FAIR is an acronym for 'findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable', intended to more clearly define what is meant by the term 'open access' and make the concept easier to discuss.[47][48] Initially proposed in March 2016, it has subsequently been endorsed by organisations such as the European Commission and the G20.[49][50] Note, however, that FAIR principles include "A1.2: The protocol allows for an authentication and authorisation procedure where necessary."[51] This means that a FAIR dataset may be either closed (restricted access) or open (no access restrictions). So, only FAIR data without access restrictions are open access.

Features

[edit]The emergence of open science or open research has brought to light a number of controversial and hotly-debated topics.

Scholarly publishing invokes various positions and passions. For example, authors may spend hours struggling with diverse article submission systems, often converting document formatting between a multitude of journal and conference styles, and sometimes spend months waiting for peer review results. The drawn-out and often contentious societal and technological transition to Open Access and Open Science/Open Research, particularly across North America and Europe (Latin America has already widely adopted "Acceso Abierto" since before 2000[52]) has led to increasingly entrenched positions and much debate.[53]

The area of (open) scholarly practices increasingly sees a role for policy-makers and research funders[54][55][56] giving focus to issues such as career incentives, research evaluation and business models for publicly funded research. Plan S and AmeliCA[57] (Open Knowledge for Latin America) caused a wave of debate in scholarly communication in 2019 and 2020.[58][59]

Licenses

[edit]

Subscription-based publishing typically requires transfer of copyright from authors to the publisher so that the latter can monetise the process via dissemination and reproduction of the work.[61][62][63][64] With OA publishing, typically authors retain copyright to their work, and license its reproduction to the publisher.[65] Retention of copyright by authors can support academic freedoms by enabling greater control of the work (e.g. for image re-use) or licensing agreements (e.g. to allow dissemination by others).[66]

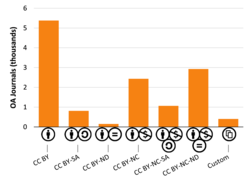

The most common licenses used in open access publishing are Creative Commons.[67] The widely used CC BY license is one of the most permissive, only requiring attribution to be allowed to use the material (and allowing derivations and commercial use).[68] A range of more restrictive Creative Commons licenses are also used. More rarely, some of the smaller academic journals use custom open access licenses.[67][69] Some publishers (e.g. Elsevier) use "author nominal copyright" for OA articles, where the author retains copyright in name only and all rights are transferred to the publisher.[70][71][72]

Funding

[edit]Since open access publication does not charge readers, there are many financial models used to cover costs by other means.[73] Open access can be provided by commercial publishers, who may publish open access as well as subscription-based journals, or dedicated open-access publishers such as Public Library of Science (PLOS) and BioMed Central. Another source of funding for open access can be institutional subscribers. One example is the Subscribe to Open publishing model introduced by Annual Reviews; if the subscription revenue goal is met, the given journal's volume is published open access.[74] The number of journals implementing this model grew from 192 in 2024 to 378 in 2025.[75]

Advantages and disadvantages of open access have generated considerable discussion amongst researchers, academics, librarians, university administrators, funding agencies, government officials, commercial publishers, editorial staff and society publishers.[76] Reactions of existing publishers to open access journal publishing have ranged from moving with enthusiasm to a new open access business model, to experiments with providing as much free or open access as possible, to active lobbying against open access proposals. There are many publishers that started up as open access-only publishers, such as PLOS, Hindawi Publishing Corporation, Frontiers in... journals, MDPI and BioMed Central.

Article processing charges

[edit]

Some open access journals (under the gold, and hybrid models) generate revenue by charging publication fees in order to make the work openly available at the time of publication.[77][26][27] The money might come from the author but more often comes from the author's research grant or employer.[78] While the payments are typically incurred per article published (e.g. BMC or PLOS journals), some journals apply them per manuscript submitted (e.g. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics until recently) or per author (e.g. PeerJ).

Charges typically range from $1,000–$3,000 ($5,380 for Nature Communications)[79][60][80] but can be under $10,[81] close to $5,000[82] or well over $10,000.[83] APCs vary greatly depending on subject and region and are most common in scientific and medical journals (43% and 47% respectively), and lowest in arts and humanities journals (0% and 4% respectively).[84] APCs can also depend on a journal's impact factor.[85][86][87][88] Some publishers (e.g. eLife and Ubiquity Press) have released estimates of their direct and indirect costs that set their APCs.[89][90] Hybrid OA generally costs more than gold OA and can offer a lower quality of service.[21] A particularly controversial practice in hybrid open access journals is "double dipping", where both authors and subscribers are charged.[22]

By comparison, journal subscriptions equate to $3,500–$4,000 per article published by an institution, but are highly variable by publisher (and some charge page fees separately). This has led to the assessment that there is enough money "within the system" to enable full transition to OA.[91] However, there is ongoing discussion about whether the change-over offers an opportunity to become more cost-effective or promotes more equitable participation in publication.[92] Concern has been noted that increasing subscription journal prices will be mirrored by rising APCs, creating a barrier to less financially privileged authors.[93][94][95]

The inherent bias of the current APC-based OA publishing perpetuates this inequality through the 'Matthew effect' (the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer). The switch from pay-to-read to pay-to-publish has left essentially the same people behind, with some academics not having enough purchasing power (individually or through their institutions) for either option.[96] Some gold OA publishers will waive all or part of the fee for authors from less developed economies. Steps are normally taken to ensure that peer reviewers do not know whether authors have requested, or been granted, fee waivers, or to ensure that every paper is approved by an independent editor with no financial stake in the journal.[citation needed] The main argument against requiring authors to pay a fee, is the risk to the peer review system, diminishing the overall quality of scientific journal publishing.[citation needed]

Subsidized or no-fee

[edit]No-fee open access journals, also known as "platinum" or "diamond"[26][27] do not charge either readers or authors.[97] These journals use a variety of business models including subsidies, advertising, membership dues, endowments, or volunteer labour.[98][92] Subsidising sources range from universities, libraries and museums to foundations, societies or government agencies.[98] Some publishers may cross-subsidise from other publications or auxiliary services and products.[98] For example, most APC-free journals in Latin America are funded by higher education institutions and are not conditional on institutional affiliation for publication.[92] Conversely, Knowledge Unlatched crowdsources funding in order to make monographs available open access.[99]

Estimates of prevalence vary, but approximately 10,000 journals without APC are listed in DOAJ[100] and the Free Journal Network.[101][102] APC-free journals tend to be smaller and more local-regional in scope.[103][104] Some also require submitting authors to have a particular institutional affiliation.[103]

Preprint use

[edit]

A "preprint" is typically a version of a research paper that is shared on an online platform prior to, or during, a formal peer review process.[105][106][107] Preprint platforms have become popular due to the increasing drive towards open access publishing and can be publisher- or community-led. A range of discipline-specific or cross-domain platforms now exist.[108] The posting of pre-prints (or authors' manuscript versions) is consistent with the Green Open Access model.[citation needed]

Effect of preprints on later publication

[edit]A persistent concern surrounding preprints is that work may be at risk of being plagiarised or "scooped" – meaning that the same or similar research will be published by others without proper attribution to the original source – if publicly available but not yet associated with a stamp of approval from peer reviewers and traditional journals.[109] These concerns are often amplified as competition increases for academic jobs and funding, and perceived to be particularly problematic for early-career researchers and other higher-risk demographics within academia.[citation needed]

However, preprints, in fact, protect against scooping.[110] Considering the differences between traditional peer-review based publishing models and deposition of an article on a preprint server, "scooping" is less likely for manuscripts first submitted as preprints. In a traditional publishing scenario, the time from manuscript submission to acceptance and to final publication can range from a few weeks to years, and go through several rounds of revision and resubmission before final publication.[111] During this time, the same work will have been extensively discussed with external collaborators, presented at conferences, and been read by editors and reviewers in related areas of research. Yet, there is no official open record of that process (e.g., peer reviewers are normally anonymous, reports remain largely unpublished), and if an identical or very similar paper were to be published while the original was still under review, it would be impossible to establish provenance.[citation needed]

Preprints provide a time-stamp at the time of publication, which helps to establish the "priority of discovery" for scientific claims.[112] This means that a preprint can act as proof of provenance for research ideas, data, code, models, and results.[113] The fact that the majority of preprints come with a form of permanent identifier, usually a digital object identifier (DOI), also makes them easy to cite and track. Thus, if one were to be "scooped" without adequate acknowledgement, this would be a case of academic misconduct and plagiarism, and could be pursued as such.

There is no evidence that "scooping" of research via preprints exists, not even in communities that have broadly adopted the use of the arXiv server for sharing preprints since 1991. If the unlikely case of scooping emerges as the growth of the preprint system continues, it can be dealt with as academic malpractice. ASAPbio includes a series of hypothetical scooping scenarios as part of its preprint FAQ, finding that the overall benefits of using preprints vastly outweigh any potential issues around scooping.[note 1] Indeed, the benefits of preprints, especially for early-career researchers, seem to outweigh any perceived risk: rapid sharing of academic research, open access without author-facing charges, establishing priority of discoveries, receiving wider feedback in parallel with or before peer review, and facilitating wider collaborations.[110]

Archiving

[edit]The "green" route to OA refers to author self-archiving, in which a version of the article (often the peer-reviewed version before editorial typesetting, called "postprint") is posted online to an institutional or subject repository. This route is often dependent on journal or publisher policies,[note 2] which can be more restrictive and complicated than respective "gold" policies regarding deposit location, license, and embargo requirements. Some publishers require an embargo period before deposition in public repositories,[114] arguing that immediate self-archiving risks loss of subscription income.

Embargo periods

[edit]

Embargoes are imposed by between 20 and 40% of journals,[116][117] during which time an article is paywalled before permitting self-archiving (green OA) or releasing a free-to-read version (bronze OA).[118][119] Embargo periods typically vary from 6–12 months in STEM and >12 months in humanities, arts and social sciences.[92] Embargo-free self-archiving has not been shown to affect subscription revenue,[120] and tends to increase readership and citations.[121][122] Embargoes have been lifted on particular topics for either limited times or ongoing (e.g. Zika outbreaks[123] or indigenous health[124]). Plan S includes zero-length embargoes on self-archiving as a key principle.[92]

Motivations

[edit]Open access (mostly green and gratis) began to be sought and provided worldwide by researchers when the possibility itself was opened by the advent of Internet and the World Wide Web. The momentum was further increased by a growing movement for academic journal publishing reform, and with it gold and libre OA.[citation needed]

The premises behind open access publishing are that there are viable funding models to maintain traditional peer review standards of quality while also making the following changes:

- Rather than making journal articles accessible through a subscription business model, all academic publications could be made free to read and published with some other cost-recovery model, such as publication charges, subsidies, or charging subscriptions only for the print edition, with the online edition gratis or "free to read".[125]

- Rather than applying traditional notions of copyright to academic publications, they could be libre or "free to build upon".[125]

An obvious advantage of open access journals is the free access to scientific papers regardless of affiliation with a subscribing library and improved access for the general public; this is especially true in developing countries. Lower costs for research in academia and industry have been claimed in the Budapest Open Access Initiative,[126] although others have argued that OA may raise the total cost of publication,[127] and further increase economic incentives for exploitation in academic publishing.[128] The open access movement is motivated by the problems of social inequality caused by restricting access to academic research, which favor large and wealthy institutions with the financial means to purchase access to many journals, as well as the economic challenges and perceived unsustainability of academic publishing.[125][129]

Stakeholders and concerned communities

[edit]The intended audience of research articles is usually other researchers. Open access helps researchers as readers by opening up access to articles that their libraries do not subscribe to. All researchers benefit from open access as no library can afford to subscribe to every scientific journal and most can only afford a small fraction of them – this is known as the "serials crisis".[130]

Open access extends the reach of research beyond its immediate academic circle. An open access article can be read by anyone – a professional in the field, a researcher in another field, a journalist, a politician or civil servant, or an interested layperson. Indeed, a 2008 study revealed that mental health professionals are roughly twice as likely to read a relevant article if it is freely available.[131]

Research funders

[edit]Research funding agencies and universities want to ensure that the research they fund and support in various ways has the greatest possible research impact.[132] As a means of achieving this, research funders are beginning to expect open access to the research they support. Many of them (including all UK Research Councils) have already adopted open-access mandates, and others are on the way to do so (see ROARMAP).

Universities

[edit]A growing number of universities are providing institutional repositories in which their researchers can deposit their published articles. Some open access advocates believe that institutional repositories will play a very important role in responding to open-access mandates from funders.[133]

In May 2005, 16 major Dutch universities cooperatively launched DAREnet, the Digital Academic Repositories, making over 47,000 research papers available.[134] From 2 June 2008, DAREnet has been incorporated into the scholarly portal NARCIS.[135] By 2019, NARCIS provided access to 360,000 open access publications from all Dutch universities, KNAW, NWO and a number of scientific institutes.[136]

In 2011, a group of universities in North America formed the Coalition of Open Access Policy Institutions (COAPI).[137] Starting with 21 institutions where the faculty had either established an open access policy or were in the process of implementing one, COAPI now has nearly 50 members. These institutions' administrators, faculty and librarians, and staff support the international work of the Coalition's awareness-raising and advocacy for open access.

In 2012, the Harvard Open Access Project released its guide to good practices for university open-access policies,[138] focusing on rights-retention policies that allow universities to distribute faculty research without seeking permission from publishers. As of November 2023, Rights retention policies are being adopted by an increasing number of UK universities as well.

In 2013 a group of nine Australian universities formed the Australian Open Access Strategy Group (AOASG) to advocate, collaborate, raise awareness, and lead and build capacity in the open access space in Australia.[139] In 2015, the group expanded to include all eight New Zealand universities and was renamed the Australasian Open Access Support Group.[140] It was then renamed the Australasian Open Access Strategy Group, highlighting its emphasis on strategy. The awareness raising activities of the AOASG include presentations, workshops, blogs, and a webinar series on open access issues.[141]

Libraries and librarians

[edit]As information professionals, librarians are often vocal and active advocates of open access. These librarians believe that open access promises to remove both the price and permission barriers that undermine library efforts to provide access to scholarship, as well as helping to address the serials crisis.[142] Open access provides a complement to library access services such as interlibrary loan, supporting researchers' needs for immediate access to scholarship.[143] Librarians and library associations also lead education and outreach initiatives to faculty, administrators, the library community, and the public about the benefits of open access.

Many library associations have either signed major open access declarations or created their own. For example, IFLA have produced a Statement on Open Access.[144] The Association of Research Libraries has documented the need for increased access to scholarly information, and was a leading founder of the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC).[145][146] Librarians and library associations also develop and share informational resources on scholarly publishing and open access to research; the Scholarly Communications Toolkit[147] developed by the Association of College and Research Libraries of the American Library Association is one example of this work.

At most universities, the library manages the institutional repository, which provides free access to scholarly work by the university's faculty. The Canadian Association of Research Libraries has a program[148] to develop institutional repositories at all Canadian university libraries. An increasing number of libraries provide publishing or hosting services for open access journals, with the Library Publishing Coalition as a membership organisation.[149]

In 2013, open access activist Aaron Swartz was posthumously awarded the American Library Association's James Madison Award for being an "outspoken advocate for public participation in government and unrestricted access to peer-reviewed scholarly articles".[150][151] In March 2013, the entire editorial board and the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Library Administration resigned en masse, citing a dispute with the journal's publisher.[152] One board member wrote of a "crisis of conscience about publishing in a journal that was not open access" after the death of Aaron Swartz.[153][154]

Public

[edit]The public may benefit from open access to scholarly research for many reasons. Advocacy groups such as SPARC's Alliance for Taxpayer Access in the US argue that most scientific research is paid for by taxpayers through government grants, who have a right to access the results of what they have funded.[155] Examples of people who might wish to read scholarly literature include individuals with medical conditions and their family members, serious hobbyists or "amateur" scholars (e.g. amateur astronomers), and high school and junior college students. Additionally, professionals in many fields, such as those doing research in private companies, start-ups, and hospitals, may not have access to publications behind paywalls, and OA publications are the only type that they can access in practice.

Even those who do not read scholarly articles benefit indirectly from open access.[156] For example, patients benefit when their doctor and other health care professionals have access to the latest research. Advocates argue that open access speeds research progress, productivity, and knowledge translation.[157]

Low-income countries

[edit]In developing nations, open access archiving and publishing acquires a unique importance.[158] Scientists, health care professionals, and institutions in developing nations often do not have the capital necessary to access scholarly literature.

Many open access projects involve international collaboration. For example, the SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online),[159] is a comprehensive approach to full open access journal publishing, involving a number of Latin American countries. Bioline International, a non-profit organization dedicated to helping publishers in developing countries is a collaboration of people in the UK, Canada, and Brazil; the Bioline International Software is used around the world. Research Papers in Economics (RePEc), is a collaborative effort of over 100 volunteers in 45 countries. The Public Knowledge Project in Canada developed the open-source publishing software Open Journal Systems (OJS), which is now in use around the world, for example by the African Journals Online group, and one of the most active development groups is Portuguese. This international perspective has resulted in advocacy for the development of open-source appropriate technology and the necessary open access to relevant information for sustainable development.[160][161]

History

[edit]This section should include a summary of, or be summarized in, History of open access. (May 2018) |

Extent

[edit]Various studies have investigated the extent of open access. A study published in 2010 showed that roughly 20% of the total number of peer-reviewed articles published in 2008 could be found openly accessible.[163] Another study found that by 2010, 7.9% of all academic journals with impact factors were gold open access journals and showed a broad distribution of Gold Open Access journals throughout academic disciplines.[164] A study of random journals from the citations indexes AHSCI, SCI and SSCI in 2013 came to the result that 88% of the journals were closed access and 12% were open access.[26] In August 2013, a study done for the European Commission reported that 50% of a random sample of all articles published in 2011 as indexed by Scopus were freely accessible online by the end of 2012.[165][166][167] A 2017 study by the Max Planck Society put the share of gold access articles in pure open access journals at around 13 percent of total research papers.[168]

In 2009, there were approximately 4,800 active open access journals, publishing around 190,000 articles.[169] As of February 2019, over 12,500 open access journals are listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals.[170]

A 2013-2018 report (GOA4) found that in 2018 over 700,000 articles were published in gold open access in the world, of which 42% was in journals with no author-paid fees.[79] The figure varies significantly depending on region and kind of publisher: 75% if university-run, over 80% in Latin America, but less than 25% in Western Europe.[79] However, Crawford's study did not count open access articles published in "hybrid" journals (subscription journals that allow authors to make their individual articles open in return for payment of a fee). More comprehensive analyses of the scholarly literature suggest that this resulted in a significant underestimation of the prevalence of author-fee-funded OA publications in the literature.[173] Crawford's study also found that although a minority of open access journals impose charges on authors, a growing majority of open access articles are published under this arrangement, particularly in the science disciplines (thanks to the enormous output of open access "mega journals", each of which may publish tens of thousands of articles in a year and are invariably funded by author-side charges—see Figure 10.1 in GOA4).

According to Scopus database in August, 2024, 46.2% of works, indexed therein and published in 2023, had some form of open access. More than half of the OA publications (27.5% of all indexed works in 2023) were in fully Gold Open Access sources, 16.7% of all were in Green OA sources (i.e. which allow for self-archiving by authors), 9.2 % in Hybrid Gold OA sources (such as journals, which have open access and behind-paywall articles in the same issue), and 10.6 % were in Bronze OA sources (free-to-read on the publishers' websites).[174]

The adoption of Open Access publishing varies significantly from publisher to publisher, as shown in Fig. OA-Plot, where only the oldest (traditional) publishers are shown, but not the newer publishers, that use the Open Access model exclusively. This plot shows, that since 2010 the Institute of Physics has the largest percentage of OA publications, while the American Chemical Society has the lowest. Both the IOP and the ACS are non-profit publishers. The increase in OA percentage for articles published before ca. 1923 is related to the expiration of a 100-year copyright term. Some publishers (e.g. IOP and ACS made many such articles available as Open Access, while others (Elsevier in particular) did not.

The Registry of Open Access Repositories (ROAR) indexes the creation, location and growth of open access open access-repositories and their contents.[175] As of February 2019, over 4,500 institutional and cross-institutional repositories have been registered in ROAR.[176]

Effects on scholarly publishing

[edit]Article impact

[edit]

Since published articles report on research that is typically funded by government or university grants, the more the article is used, cited, applied and built upon, the better for research as well as for the researcher's career.[184][185]

Some professional organizations have encouraged use of open access: in 2001, the International Mathematical Union communicated to its members that "Open access to the mathematical literature is an important goal" and encouraged them to "[make] available electronically as much of our own work as feasible" to "[enlarge] the reservoir of freely available primary mathematical material, particularly helping scientists working without adequate library access".[186]

Readership

[edit]OA articles are generally viewed online and downloaded more often than paywalled articles and that readership continues for longer.[178][187] Readership is especially higher in demographics that typically lack access to subscription journals (in addition to the general population, this includes many medical practitioners, patient groups, policymakers, non-profit sector workers, industry researchers, and independent researchers).[188] OA articles are more read on publication management programs such as Mendeley.[182] Open access practices can reduce publication delays, an obstacle which led some research fields such as high-energy physics to adopt widespread preprint access.[189]

Citation rate

[edit]

A main reason authors make their articles openly accessible is to maximize their citation impact.[190] Open access articles are typically cited more often than equivalent articles requiring subscriptions.[2][191][192][193][194] This 'citation advantage' was first reported in 2001.[195] Although two major studies dispute this claim,[196][187] the consensus of multiple studies support the effect,[177][197] with measured OA citation advantage varying in magnitude between 1.3-fold to 6-fold depending on discipline.[193][198][199]

Citation advantage is most pronounced in OA articles in hybrid journals (compared to the non-OA articles in those same journals),[200] and with articles deposited in green OA repositories.[163] Notably, green OA articles show similar benefits to citation counts as gold OA articles.[199][194] Articles in gold OA journals are typically cited at a similar frequency to paywalled articles.[201] Citation advantage increases the longer an article has been published.[178]

Altmetrics

[edit]In addition to format academic citation, other forms of research impact (altmetrics) may be affected by OA publishing,[188][194] constituting a significant "amplifier" effect for science published on such platforms.[183] Initial studies suggest that OA articles are more referenced in blogs,[202] on Twitter,[182] and on English Wikipedia.[183] The OA advantage in altmetrics may be smaller than the advantage in academic citations, although findings are mixed.[203][194][199]

Journal impact factor

[edit]Journal impact factor (JIF) measures the average number of citations of articles in a journal over a two-year window. It is commonly used as a proxy for journal quality, expected research impact for articles submitted to that journal, and of researcher success.[204][205] In subscription journals, impact factor correlates with overall citation count, however this correlation is not observed in gold OA journals.[206]

Open access initiatives like Plan S typically call on a broader adoption and implementation of the Leiden Manifesto[note 3] and the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) alongside fundamental changes in the scholarly communication system.[note 4]

Peer review processes

[edit]Peer review of research articles prior to publishing has been common since the 18th century.[207][208] Commonly reviewer comments are only revealed to the authors and reviewer identities kept anonymous.[209][210] The rise of OA publishing has also given rise to experimentation in technologies and processes for peer review.[211] Increasing transparency of peer review and quality control includes posting results to preprint servers,[212] preregistration of studies,[213] open publishing of peer reviews,[214] open publishing of full datasets and analysis code,[215][216] and other open science practices.[217][218][219] It is proposed that increased transparency of academic quality control processes makes audit of the academic record easier.[214][220] Additionally, the rise of OA megajournals has made it viable for their peer review to focus solely on methodology and results interpretation whilst ignoring novelty.[221][222] Major criticisms of the influence of OA on peer review have included that if OA journals have incentives to publish as many articles as possible then peer review standards may fall (as aspect of predatory publishing), increased use of preprints may populate the academic corpus with un-reviewed junk and propaganda, and that reviewers may self-censor if their identity is open. Some advocates propose that readers will have increased skepticism of preprint studies - a traditional hallmark of scientific inquiry.[92]

Predatory publishing

[edit]Predatory publishers present themselves as academic journals but use lax or no peer review processes coupled with aggressive advertising in order to generate revenue from article processing charges from authors. The definitions of 'predatory', 'deceptive', or 'questionable' publishers/journals are often vague, opaque, and confusing, and can also include fully legitimate journals, such as those indexed by PubMed Central.[223] In this sense, Grudniewicz et al.[224] proposed a consensus definition that needs to be shared: "Predatory journals and publishers are entities that prioritize self-interest at the expense of scholarship and are characterized by false or misleading information, deviation from best editorial and publication practices, a lack of transparency, and/or the use of aggressive and indiscriminate solicitation practices."

In this way, predatory journals exploit the OA model by deceptively removing the main value added by the journal (peer review) and parasitize the OA movement, occasionally hijacking or impersonating other journals.[225][226] The rise of such journals since 2010[227][228] has damaged the reputation of the OA publishing model as a whole, especially via sting operations where fake papers have been successfully published in such journals.[229] Although commonly associated with OA publishing models, subscription journals are also at risk of similar lax quality control standards and poor editorial policies.[230][231][232] OA publishers therefore aim to ensure quality via auditing by registries such as DOAJ, OASPA and SciELO and comply to a standardised set of conditions. A blacklist of predatory publishers is also maintained by Cabell's blacklist (a successor to Beall's List).[233][234] Increased transparency of the peer review and publication process has been proposed as a way to combat predatory journal practices.[92][214][235]

Open irony

[edit]Open irony refers to the situation where a scholarly journal article advocates open access but the article itself is only accessible by paying a fee to the journal publisher to read the article.[236][237][238] This has been noted in many fields, with more than 20 examples appearing since around 2010, including in widely-read journals such as The Lancet, Science and Nature. In 2012 Duncan Hull proposed the Open Access Irony award to publicly humiliate journals that publish these kinds of papers.[239] Examples of these have been shared and discussed on social media using the hashtag #openirony. Typically, these discussions are humorous exposures of articles/editorials that are pro-open access, but locked behind paywalls. The main concern that motivates these discussions is that restricted access to public scientific knowledge is slowing scientific progress.[238] The practice has been justified as important for raising awareness of open access.[240]

Infrastructure

[edit]

Databases and repositories

[edit]Multiple databases exist for open access articles, journals and datasets. These databases overlap, however each has different inclusion criteria, which typically include extensive vetting for journal publication practices, editorial boards and ethics statements. The main databases of open access articles and journals are DOAJ and PMC. In the case of DOAJ, only fully gold open access journals are included, whereas PMC also hosts articles from hybrid journals.

There are also a number of preprint servers which host articles that have not yet been reviewed as open access copies.[242][243] These articles are subsequently submitted for peer review by both open access and subscription journals, however the preprint always remains openly accessible. A list of preprint servers is maintained at ResearchPreprints.[244]

For articles that are published in closed access journals, some authors will deposit a postprint copy in an open-access repository, where it can be accessed for free.[245][246][247][175][248] Most subscription journals place restrictions on which version of the work may be shared or require an embargo period following the original date of publication. What is deposited can therefore vary, either a preprint or the peer-reviewed postprint, either the author's refereed and revised final draft or the publisher's version of record, either immediately deposited or after several years.[249] Repositories may be specific to an institution, a discipline (e.g.arXiv), a scholarly society (e.g. MLA's CORE Repository), or a funder (e.g. PMC). Although the practice was first formally proposed in 1994,[250][251] self-archiving was already being practiced by some computer scientists in local FTP archives in the 1980s (later harvested by CiteSeer).[252] The SHERPA/RoMEO site maintains a list of the different publisher copyright and self-archiving policies[253] and the ROAR database hosts an index of the repositories themselves.[254][255]

Representativeness in proprietary databases

[edit]Uneven coverage of journals in the major commercial citation index databases (such as Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed)[256][257][258][259] has strong effects on evaluating both researchers and institutions (e.g. the UK Research Excellence Framework or Times Higher Education ranking[note 5][260][261]). While these databases primarily select based on process and content quality, there has been concern that their commercial nature may skew their assessment criteria and representation of journals outside of Europe and North America.[92][71] At the time of that study in 2018, there were no comprehensive, open source or non-commercial academic databases.[262] However, in more recent years, The Lens emerged as a suitable outside-paywalls universal academic database.

Distribution

[edit]Like the self-archived green open access articles, most gold open access journal articles are distributed via the World Wide Web,[1] due to low distribution costs, increasing reach, speed, and increasing importance for scholarly communication. Open source software is sometimes used for open-access repositories,[263] open access journal websites,[264] and other aspects of open access provision and open access publishing.

Access to online content requires Internet access, and this distributional consideration presents physical and sometimes financial barriers to access.

There are various open access aggregators that list open access journals or articles. ROAD (the Directory of Open Access Scholarly Resources)[265] synthesizes information about open access journals and is a subset of the ISSN register. SHERPA/RoMEO lists international publishers that allow the published version of articles to be deposited in institutional repositories. The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) contains over 12,500 peer-reviewed open access journals for searching and browsing.[266][170]

Open access articles can be found with a web search, using any general search engine or those specialized for the scholarly and scientific literature, such as Google Scholar, OAIster, base-search.net,[267] and CORE[268] Many open-access repositories offer a programmable interface to query their content. Some of them use a generic protocol, such as OAI-PMH (e.g., base-search.net[267]). In addition, some repositories propose a specific API, such as the arXiv API, the Dissemin API, the Unpaywall/oadoi API, or the base-search API.

In 1998, several universities founded the Public Knowledge Project to foster open access, and developed the open-source journal publishing system Open Journal Systems, among other scholarly software projects. As of 2010, it was being used by approximately 5,000 journals worldwide.[269]

Several initiatives provide an alternative to the English language dominance of existing publication indexing systems, including Index Copernicus (Polish), SciELO (Portuguese, Spanish) and Redalyc (Spanish).

Policies and mandates

[edit]Many universities, research institutions and research funders have adopted mandates requiring their researchers to make their research publications open access.[270] For example, Research Councils UK spent nearly £60m on supporting their open access mandate between 2013 and 2016.[271] New mandates are often announced during the Open Access Week, that takes place each year during the last full week of October.

The idea of mandating self-archiving was raised at least as early as 1998.[272] Since 2003[273] efforts have been focused on open access mandating by the funders of research: governments,[274] research funding agencies,[275] and universities.[276] Some publishers and publisher associations have lobbied against introducing mandates.[277][278][279]

In 2002, the University of Southampton's School of Electronics & Computer Science became one of the first schools to implement a meaningful mandatory open access policy, in which authors had to contribute copies of their articles to the school's repository. More institutions followed suit in the following years.[2] In 2007, Ukraine became the first country to create a national policy on open access, followed by Spain in 2009. Argentina, Brazil, and Poland are currently in the process of developing open access policies. Making master's and doctoral theses open access is an increasingly popular mandate by many educational institutions.[2]

In the US, the NIH Public Access Policy has required since 2008 that papers describing research funded by the National Institutes of Health must be available to the public free through PubMed Central (PMC) within 12 months of publication. In 2022, US President Joe Biden's Office of Science and Technology Policy issued a memorandum calling for the removal of the 12-month embargo.[280] By the end of 2025, US federal agencies must require all results (papers, documents and data) produced as a result of US government-funded research to be available to the public immediately upon publication.[281]

In 2023, the Council of the European Union recommended the implementation of an open-access and not-for-profit model for research publishing by the European Commission and member states. These recommendations are not legally binding and received mixed reactions. While welcomed by some members of the academic community, publishers argued that the suggested model is unrealistic due to the lack of crucial funding details. Furthermore, the council's recommendations raised concerns within the publishing industry regarding the potential implications, and they also emphasized the importance of research integrity and the need for member states to address predatory journals and paper mills.[282]

In 2024, the Gates Foundation announced a "preprint-centric" open access policy, and their intention to stop paying APCs.[283] In 2024, the government of Japan also announced a Green open access policy, requiring that government-funded research be made freely available on institutional preprint repositories from April 2025.[284]

Compliance

[edit]As of March 2021, open-access mandates have been registered by over 100 research funders and 800 universities worldwide, compiled in the Registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies.[285] As these sorts of mandates increase in prevalence, collaborating researchers may be affected by several at once. Tools such as SWORD can help authors manage sharing between repositories.[2]

Compliance rates with voluntary open access policies remain low (as low as 5%).[2] However it has been demonstrated that more successful outcomes are achieved by policies that are compulsory and more specific, such as specifying maximum permissible embargo times.[2][286] Compliance with compulsory open-access mandates varies between funders from 27% to 91% (averaging 67%).[2][287] From March 2021, Google Scholar started tracking and indicating compliance with funders' open-access mandates, although it only checks whether items are free-to-read, rather than openly licensed.[288]

Inequality and open access

[edit]Gender inequality

[edit]Gender inequality favoring men can be found in many disciplines, including political science, economics and neurology, and critical care research.[289] For instance, in critical care research, 30.8% of the 18,483 research articles published between 2008 and 2018 were led by female authors and were more likely to be published in lower-impact journals than those led by male authors.[290] Open access publishing may improve the visibility of female researchers both inside and outside academia, but without deliberate support of female researchers, open access publishing may exacerbate gender inequality.[289]

High-income–low-income country inequality

[edit]A 2022 study has found "most OA articles were written by authors in high-income countries, and there were no articles in Mirror journals by authors in low-income countries."[291] "One of the great ironies of open access is that you grant authors around the world the ability to finally read the scientific literature that was completely closed off to them, but it ends up excluding them from publishing in the same journals" says Emilio Bruna, a scholar at the University of Florida in Gainesville.[292]

By country

[edit]See also

[edit]- Access to knowledge movement

- Altmetrics

- Copyright policies of academic publishers

- Freedom of information

- Guerilla Open Access

- Lists of academic journals

- List of open access journals

- Open Access Button

- Open access monograph

- Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association

- Open Access Week

- Open data

- Open educational resources

- Open government

- Open Journal Systems

- Predatory open access publishing

- Right to Internet access

- Category:Open access journals

- Category:Open access by country

- Category:Publication management software

Notes

[edit]- ^ "ASAPbio FAQ". Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2019..

- ^ "SHERPA/RoMEO". Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019. database.

- ^ "The Leiden Manifesto for Research Metrics". Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2019. 2015.

- ^ "Plan S implementation guidelines". Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2019., February 2019.

- ^ Publications in journals listed in the WoS has a large effect on the UK Research Excellence Framework. Bibliographic data from Scopus represents more than 36% of assessment criteria in THE rankings.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Suber, Peter. "Open Access Overview". Archived from the original on 19 May 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Swan, Alma (2012). "Policy guidelines for the development and promotion of open access". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Diedrich V, Zweerink K (2024). "Elder B. Plant Dermatitis". Emerg Med Clin North Am. 42 (3): 613–638. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2024.03.001. PMID 38925778.

- ^ Hill GA, Mattacotti V (1934). "The Toxic Principle of the Poison Ivy". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 56 (12): 2736–2738. Bibcode:1934JAChS..56.2736H. doi:10.1021/ja01327a064.

- ^ Schöpfel, Joachim; Prost, Hélène (2013). "Degrees of secrecy in an open environment. The case of electronic theses and dissertations". ESSACHESS – Journal for Communication Studies. 6 (2(12)): 65–86. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014.

- ^ Schwartz, Meredith (2012). "Directory of Open Access Books Goes Live". Library Journal. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Terms and conditions for the use and redistribution of Sentinel data" (PDF). No. version 1.0. European Space Agency. July 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Simard, Marc-André; Ghiasi, Gita; Mongeon, Philippe; Larivière, Vincent (9 August 2022). Baccini, Alberto (ed.). "National differences in dissemination and use of open access literature". PLOS One. 17 (8) e0272730. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1772730S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0272730. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9362937. PMID 35943972.

- ^ "DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals". doaj.org. 1 May 2013. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013.

- ^ Morrison, Heather (31 December 2018). "Dramatic Growth of Open Access". Scholars Portal Dataverse. hdl:10864/10660.

- ^ "PMC full journal list download". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 7 March 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ "NLM Catalog". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Schroter, Sara; Tite, Leanne (2006). "Open access publishing and author-pays business models: a survey of authors' knowledge and perceptions". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (3): 141–148. doi:10.1177/014107680609900316. PMC 1383760. PMID 16508053.

- ^ Eve, Martin Paul (3 December 2023). "Introduction, or why open access?". Open Access and the Humanities. Cambridge Core. pp. 1–42. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316161012.003. ISBN 978-1-107-09789-6. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ a b Gadd, Elizabeth; Troll Covey, Denise (1 March 2019). "What does 'green' open access mean? Tracking twelve years of changes to journal publisher self-archiving policies". Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. 51 (1): 106–122. doi:10.1177/0961000616657406. ISSN 0961-0006. S2CID 34955879. Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Weaver, Roger. "Subject Guides: Copyright: Keeping Control of Your Copyright". libguides.mst.edu. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Bolick, Josh (2018). "Leveraging Elsevier's Creative Commons License Requirement to Undermine Embargoes" (PDF). digitalcommons.unl.edu. Archived from the original on 22 April 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024 – via University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

- ^ Laakso, Mikael; Björk, Bo-Christer (2016). "Hybrid open access—A longitudinal study". Journal of Informetrics. 10 (4): 919–932. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2016.08.002.

- ^ Suber 2012, pp. 140–141

- ^ Suber 2012, p. 140

- ^ a b Trust, Wellcome (23 March 2016). "Wellcome Trust and COAF Open Access Spend, 2014-15". Wellcome Trust Blog. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Open access double dipping policy". Cambridge Core. Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Björk, B. C. (2017). "Growth of hybrid open access, 2009–2016". PeerJ. 5 e3878. doi:10.7717/peerj.3878. PMC 5624290. PMID 28975059.

- ^ Liuta, Ioana (26 July 2020). "Open choice vs open access: Why don't "hybrid" journals qualify for the open access fund?". Radical Access. SFU Library. Archived from the original on 31 August 2023.

- ^ Piwowar, Heather; Priem, Jason; Larivière, Vincent; Alperin, Juan Pablo; Matthias, Lisa; Norlander, Bree; Farley, Ashley; West, Jevin; Haustein, Stefanie (13 February 2018). "The state of OA: a large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles". PeerJ. 6 e4375. doi:10.7717/peerj.4375. PMC 5815332. PMID 29456894.

- ^ a b c d Fuchs, Christian; Sandoval, Marisol (2013). "The diamond model of open access publishing: Why policy makers, scholars, universities, libraries, labour unions and the publishing world need to take non-commercial, non-profit open access serious". TripleC. 13 (2): 428–443. doi:10.31269/triplec.v11i2.502.

- ^ a b c Gajović, S (31 August 2017). "Diamond Open Access in the quest for interdisciplinarity and excellence". Croatian Medical Journal. 58 (4): 261–262. doi:10.3325/cmj.2017.58.261. PMC 5577648. PMID 28857518.

- ^ a b Bosman, Jeroen; Frantsvåg, Jan Erik; Kramer, Bianca; Langlais, Pierre-Carl; Proudman, Vanessa (9 March 2021). OA Diamond Journals Study. Part 1: Findings (Report). doi:10.5281/zenodo.4558704.

- ^ Machovec, George (2013). "An Interview with Jeffrey Beall on Open Access Publishing". The Charleston Advisor. 15 (1): 50. doi:10.5260/chara.15.1.50.

- ^ Öchsner, A. (2013). "Publishing Companies, Publishing Fees, and Open Access Journals". Introduction to Scientific Publishing. SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 23–29. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-38646-6_4. ISBN 978-3-642-38645-9.

- ^ Normand, Stephanie (4 April 2018). "Is Diamond Open Access the Future of Open Access?". The IJournal: Graduate Student Journal of the Faculty of Information. 3 (2). ISSN 2561-7397. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Rosenblum, Brian; Greenberg, Marc; Bolick, Josh; Emmett, Ada; Peterson, A. Townsend (17 June 2016). "Subsidizing truly open access". Science. 352 (6292): 1405. Bibcode:2016Sci...352.1405P. doi:10.1126/science.aag0946. hdl:1808/20978. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27313033. S2CID 206650745.

- ^ By (1 June 2017). "Diamond Open Access, Societies and Mission". The Scholarly Kitchen. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Pearce, Joshua M. (2022). "The Rise of Platinum Open Access Journals with Both Impact Factors and Zero Article Processing Charges". Knowledge. 2 (2): 209–224. doi:10.3390/knowledge2020013. ISSN 2673-9585.

- ^ Himmelstein, Daniel S; Romero, Ariel Rodriguez; Levernier, Jacob G; Munro, Thomas Anthony; McLaughlin, Stephen Reid; Greshake Tzovaras, Bastian; Greene, Casey S (1 March 2018). "Sci-Hub provides access to nearly all scholarly literature". eLife. 7 e32822. doi:10.7554/eLife.32822. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 5832410. PMID 29424689. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ a b Björk, Bo-Christer (2017). "Gold, green, and black open access". Learned Publishing. 30 (2): 173–175. doi:10.1002/leap.1096. ISSN 1741-4857.

- ^ Green, Toby (2017). "We've failed: Pirate black open access is trumping green and gold and we must change our approach". Learned Publishing. 30 (4): 325–329. doi:10.1002/leap.1116. ISSN 1741-4857.

- ^ Bohannon, John (28 April 2016). "Who's downloading pirated papers? Everyone". Science. 352 (6285): 508–12. doi:10.1126/science.352.6285.508. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27126020. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Greshake, Bastian (21 April 2017). "Looking into Pandora's Box: The Content of Sci-Hub and its Usage". F1000Research. 6: 541. doi:10.12688/f1000research.11366.1. ISSN 2046-1402. PMC 5428489. PMID 28529712.

- ^ Jamali, Hamid R. (1 July 2017). "Copyright compliance and infringement in ResearchGate full-text journal articles". Scientometrics. 112 (1): 241–254. doi:10.1007/s11192-017-2291-4. ISSN 1588-2861. S2CID 189875585.

- ^ Swab, Michelle; Romme, Kristen (1 April 2016). "Scholarly Sharing via Twitter: #icanhazpdf Requests for Health Sciences Literature". Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association. 37 (1). doi:10.5596/c16-009. ISSN 1708-6892.

- ^ McKenzie, Lindsay (27 July 2017). "Sci-Hub's cache of pirated papers is so big, subscription journals are doomed, data analyst suggests". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aan7164. ISSN 0036-8075. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d Suber, Peter (2008). "Gratis and Libre Open Access". Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Suber 2012, pp. 68–69

- ^ Suber 2012, pp. 7–8

- ^ Balaji, B.; Dhanamjaya, M. (2019). "Preprints in Scholarly Communication: Re-Imagining Metrics and Infrastructures". Publications. 7 (1): 6. doi:10.3390/publications7010006.>

- ^ Wilkinson, Mark D.; Dumontier, Michel; Aalbersberg, IJsbrand Jan; Appleton, Gabrielle; et al. (15 March 2016). "The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship". Scientific Data. 3 (1): 160018. Bibcode:2016NatSD...360018W. doi:10.1038/sdata.2016.18. OCLC 961158301. PMC 4792175. PMID 26978244.

- ^ Wilkinson, Mark D.; da Silva Santos, Luiz Olavo Bonino; Dumontier, Michel; Velterop, Jan; Neylon, Cameron; Mons, Barend (1 January 2017). "Cloudy, increasingly FAIR; revisiting the FAIR Data guiding principles for the European Open Science Cloud". Information Services & Use. 37 (1): 49–56. doi:10.3233/ISU-170824. hdl:20.500.11937/53669. ISSN 0167-5265.

- ^ "European Commission embraces the FAIR principles". Dutch Techcentre for Life Sciences. 20 April 2016. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "G20 Leaders' Communique Hangzhou Summit". europa.eu. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "A1.2: The protocol allows for an authentication and authorisation procedure where necessary". GO FAIR. 14 June 2022.

- ^ "Hecho En Latinoamérica. Acceso Abierto, Revistas Académicas e Innovaciones Regionales". Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Vuong, Quan-Hoang (2018). "The (ir)rational consideration of the cost of science in transition economies". Nature Human Behaviour. 2 (1): 5. doi:10.1038/s41562-017-0281-4. PMID 30980055. S2CID 256707733.

- ^ Ross-Hellauer, Tony; Schmidt, Birgit; Kramer, Bianca (2018). "Are Funder Open Access Platforms a Good Idea?". SAGE Open. 8 (4) 2158244018816717. doi:10.1177/2158244018816717.

- ^ Vincent-Lamarre, Philippe; Boivin, Jade; Gargouri, Yassine; Larivière, Vincent; Harnad, Stevan (2016). "Estimating Open Access Mandate Effectiveness: The MELIBEA Score" (PDF). Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 67 (11): 2815–2828. arXiv:1410.2926. doi:10.1002/asi.23601. S2CID 8144721. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Future of Scholarly Publishing and Scholarly Communication: Report of the Expert Group to the European Commission. Publications Office of the European Union. 30 January 2019. ISBN 978-92-79-97238-6. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Aguado-López, Eduardo; Becerril-Garcia, Arianna (8 August 2019). "AmeliCA before Plan S – The Latin American Initiative to develop a cooperative, non-commercial, academic led, system of scholarly communication". Impact of Social Sciences. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Rob (2019). "From Coalition to Commons: Plan S and the Future of Scholarly Communication". Insights: The UKSG Journal. 32 5. doi:10.1629/uksg.453.

- ^ Pourret, Olivier; Irawan, Dasapta Erwin; Tennant, Jonathan P.; Hursthouse, Andrew; Van Hullebusch, Eric D. (1 September 2020). "The growth of open access publishing in geochemistry". Results in Geochemistry. 1 100001. Bibcode:2020ResGc...100001P. doi:10.1016/j.ringeo.2020.100001. ISSN 2666-2779. S2CID 219903509.

- ^ a b c DOAJ. "Journal metadata". doaj.org. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ Matushek, Kurt J. (2017). "Take Another Look at the Instructions for Authors". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 250 (3): 258–259. doi:10.2460/javma.250.3.258. PMID 28117640.

- ^ Bachrach, S.; Berry, R. S.; Blume, M.; von Foerster, T.; Fowler, A.; Ginsparg, P.; Heller, S.; Kestner, N.; Odlyzko, A.; Okerson, A.; Wigington, R.; Moffat, A. (1998). "Who Should Own Scientific Papers?". Science. 281 (5382): 1459–60. Bibcode:1998Sci...281.1459B. doi:10.1126/science.281.5382.1459. PMID 9750115. S2CID 36290551.

- ^ Gadd, Elizabeth; Oppenheim, Charles; Probets, Steve (2003). "RoMEO Studies 4: An Analysis of Journal Publishers" Copyright Agreements" (PDF). Learned Publishing. 16 (4): 293–308. doi:10.1087/095315103322422053. hdl:10150/105141. S2CID 40861778. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Willinsky, John (2002). "Copyright Contradictions in Scholarly Publishing". First Monday. 7 (11). doi:10.5210/fm.v7i11.1006. S2CID 39334346.

- ^ Carroll, Michael W. (2011). "Why Full Open Access Matters". PLOS Biology. 9 (11) e1001210. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001210. PMC 3226455. PMID 22140361.

- ^ Davies, Mark (2015). "Academic Freedom: A Lawyer's Perspective" (PDF). Higher Education. 70 (6): 987–1002. doi:10.1007/s10734-015-9884-8. S2CID 144222460. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ a b Frosio, Giancarlo F. (2014). "Open Access Publishing: A Literature Review". SSRN 2697412.

- ^ Peters, Diane; Margoni, Thomas (10 March 2016). "Creative Commons Licenses: Empowering Open Access". SSRN 2746044.

- ^ Dodds, Francis (2018). "The Changing Copyright Landscape in Academic Publishing". Learned Publishing. 31 (3): 270–275. doi:10.1002/leap.1157. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Morrison, Heather (2017). "From the Field: Elsevier as an Open Access Publisher". The Charleston Advisor. 18 (3): 53–59. doi:10.5260/chara.18.3.53. hdl:10393/35779.

- ^ a b Pablo Alperin, Juan; Rozemblum, Cecilia (2017). "The Reinterpretation of the Visibility and Quality of New Policies to Assess Scientific Publications". Revista Interamericana de Bibliotecología. 40 (3): 231–241. doi:10.17533/udea.rib.v40n3a04.

- ^ W. Frass; J. Cross; V. Gardner (2013). Open Access Survey: Exploring the Views of Taylor & Francis and Routledge Authors (PDF). Taylor & Francis/Routledge.

- ^ "OA journal business models". Open Access Directory. 2009–2012. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Jisc supports Subscribe to Open model". Jisc. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ Naddaf, Miryam (6 August 2025). "UK Royal Society adopts 'subscribe to open' publishing model". Nature. 644 (8076). Nature Publishing Group: 316–317. Bibcode:2025Natur.644..316N. doi:10.1038/d41586-025-02483-0. Retrieved 19 September 2025.

- ^ Markin, Pablo (25 April 2017). "The Sustainability of Open Access Publishing Models Past a Tipping Point". OpenScience. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Socha, Beata (20 April 2017). "How Much Do Top Publishers Charge for Open Access?". openscience.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Peter, Suber (2012). Open access. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-30173-2. OCLC 795846161.

- ^ a b c Walt Crawford (2019). Gold Open Access 2013-2018: Articles in Journals (GOA4) (PDF). Cites & Insights Books. ISBN 978-1-329-54713-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Kim, Sang-Jun; Park, Kay Sook (2021). "Influence of open access journals on the research community in Journal Citation Reports". Science Editing. 8 (1): 32–38. doi:10.6087/kcse.227. S2CID 233380569.

- ^ "An efficient journal". The Occasional Pamphlet. 6 March 2012. Archived from the original on 18 November 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Article processing charges". Nature Communications. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Publishing options". Nature.

- ^ Kozak, Marcin; Hartley, James (December 2013). "Publication fees for open access journals: Different disciplines-different methods". Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 64 (12): 2591–2594. doi:10.1002/asi.22972.

- ^ Björk, Bo-Christer; Solomon, David (2015). "Article Processing Charges in OA Journals: Relationship between Price and Quality". Scientometrics. 103 (2): 373–385. doi:10.1007/s11192-015-1556-z. S2CID 15966412.

- ^ Lawson, Stuart (2014), APC Pricing, Figshare, doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.1056280.v3

- ^ "Developing an Effective Market for Open Access Article Processing Charges" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Schönfelder, Nina (2018). "APCs—Mirroring the Impact Factor or Legacy of the Subscription-Based Model?". Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "Setting a fee for publication". eLife. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Ubiquity Press". www.ubiquitypress.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ Schimmer, Ralf; Geschuhn, Kai Karin; Vogler, Andreas (2015). "Disrupting the Subscription Journals" Business Model for the Necessary Large-Scale Transformation to Open Access". MPG.PuRe Repository. doi:10.17617/1.3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vanholsbeeck, Marc; Thacker, Paul; Sattler, Susanne; Ross-Hellauer, Tony; Rivera-López, Bárbara S.; Rice, Curt; Nobes, Andy; Masuzzo, Paola; Martin, Ryan; Kramer, Bianca; Havemann, Johanna; Enkhbayar, Asura; Davila, Jacinto; Crick, Tom; Crane, Harry; Tennant, Jonathan P. (11 March 2019). "Ten Hot Topics around Scholarly Publishing". Publications. 7 (2): 34. doi:10.3390/publications7020034.

- ^ Björk, B. C. (2017). "Growth of Hybrid Open Access". PeerJ. 5 e3878. doi:10.7717/peerj.3878. PMC 5624290. PMID 28975059.

- ^ Pinfield, Stephen; Salter, Jennifer; Bath, Peter A. (2016). "The 'Total Cost of Publication" in a Hybrid Open-Access Environment: Institutional Approaches to Funding Journal Article-Processing Charges in Combination with Subscriptions" (PDF). Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 67 (7): 1751–1766. doi:10.1002/asi.23446. S2CID 17356533. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Green, Toby (2019). "Is Open Access Affordable? Why Current Models Do Not Work and Why We Need Internet-Era Transformation of Scholarly Communications". Learned Publishing. 32 (1): 13–25. doi:10.1002/leap.1219. S2CID 67869151.

- ^ Pourret, Olivier; Hedding, David William; Ibarra, Daniel Enrique; Irawan, Dasapta Erwin; Liu, Haiyan; Tennant, Jonathan Peter (10 June 2021). "International disparities in open access practices in the Earth Sciences". European Science Editing. 47 e63663. doi:10.3897/ese.2021.e63663. ISSN 2518-3354. S2CID 236300530.

- ^ Koroso, Nesru H. (18 November 2015). "Diamond Open Access – UA Magazine". UA Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Suber, Peter (2 November 2006). "No-fee open-access journals". SPARC open access Newsletter. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ^ Montgomery, Lucy (2014). "Knowledge Unlatched:A Global Library Consortium Model for Funding Open Access Scholarly Books". Cultural Science. 7 (2). hdl:20.500.11937/12680.

- ^ "DOAJ search". Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Mark (20 June 2018). "Introducing the Free Journal Network – community-controlled open access publishing". Impact of Social Sciences. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Is the EU's open access plan a tremor or an earthquake?". Science|Business. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ a b Bastian, Hilda (2 April 2018). "A Reality Check on Author Access to Open Access Publishing". Absolutely Maybe. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ Crotty, David (26 August 2015). "Is it True that Most Open Access Journals Do Not Charge an APC? Sort of. It Depends". The Scholarly Kitchen. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ Ginsparg, P. (2016). "Preprint Déjà Vu". The EMBO Journal. 35 (24): 2620–2625. doi:10.15252/embj.201695531. PMC 5167339. PMID 27760783.

- ^ Tennant, Jonathan; Bauin, Serge; James, Sarah; Kant, Juliane (2018). The Evolving Preprint Landscape: Introductory Report for the Knowledge Exchange Working Group on Preprints (Report). doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/796TU.

- ^ Neylon, Cameron; Pattinson, Damian; Bilder, Geoffrey; Lin, Jennifer (2017). "On the Origin of Nonequivalent States: How We Can Talk about Preprints". F1000Research. 6: 608. doi:10.12688/f1000research.11408.1. PMC 5461893. PMID 28620459.

- ^ Balaji, B.; Dhanamjaya, M. (2019). "Preprints in Scholarly Communication: Re-Imagining Metrics and Infrastructures". Publications. 7 (1): 6. doi:10.3390/publications7010006.

- ^ Bourne, Philip E.; Polka, Jessica K.; Vale, Ronald D.; Kiley, Robert (2017). "Ten simple rules to consider regarding preprint submission". PLOS Computational Biology. 13 (5) e1005473. Bibcode:2017PLSCB..13E5473B. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005473. PMC 5417409. PMID 28472041.