Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

H II region

View on Wikipedia

An H II region is a region of interstellar atomic hydrogen that is ionized.[1] It is typically in a molecular cloud of partially ionized gas in which star formation has recently taken place, with a size ranging from one to hundreds of light years, and density from a few to about a million particles per cubic centimetre. The Orion Nebula, now known to be an H II region, was observed in 1610 by Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc by telescope, the first such object discovered.

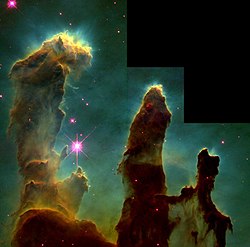

The regions may be of any shape because the distribution of the stars and gas inside them is irregular. The short-lived blue stars created in these regions emit copious amounts of ultraviolet light that ionize the surrounding gas. H II regions—sometimes several hundred light-years across—are often associated with giant molecular clouds. They often appear clumpy and filamentary, sometimes showing intricate shapes such as the Horsehead Nebula. H II regions may give birth to thousands of stars over a period of several million years. Supernova explosions and strong stellar winds from the most massive stars in the resulting star cluster ultimately disperse the remaining gas of the H II region.

H II regions can be observed at considerable distances in the universe, and the study of extragalactic H II regions (Such as NGC 604 and 206) is important in determining the distances and chemical composition of galaxies. Spiral and irregular galaxies contain many H II regions, while elliptical galaxies are almost devoid of them. In spiral galaxies, including our Milky Way, H II regions are concentrated in the spiral arms, while in irregular galaxies they are distributed chaotically. Some galaxies contain huge H II regions, which may contain tens of thousands of stars. Examples include the 30 Doradus region in the Large Magellanic Cloud and NGC 604 in the Triangulum Galaxy.

Terminology

[edit]

The term H II is pronounced "H two". "H" is the chemical symbol for hydrogen, and "II" is the Roman numeral for 2. The convention in astronomy is to use the Roman numeral I for neutral atoms, II for singly-ionised, III for doubly-ionised, and so on.[3] H II, or H+, consists of free protons. An H I region consists of neutral atomic hydrogen, and a molecular cloud of molecular hydrogen, H2.

Observations

[edit]

A few of the brightest H II regions are visible to the naked eye. However, none seem to have been noticed before the advent of the telescope in the early 17th century. Even Galileo did not notice the Orion Nebula when he first observed the star cluster within it (previously cataloged as a single star, θ Orionis, by Johann Bayer). The French observer Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc is credited with the discovery of the Orion Nebula in 1610.[4] Since that early observation large numbers of H II regions have been discovered in the Milky Way and other galaxies.[5]

William Herschel observed the Orion Nebula in 1774, and described it later as "an unformed fiery mist, the chaotic material of future suns".[6] In early days astronomers distinguished between "diffuse nebulae" (now known to be H II regions), which retained their fuzzy appearance under magnification through a large telescope, and nebulae that could be resolved into stars, now known to be galaxies external to our own.[7]

Confirmation of Herschel's hypothesis of star formation had to wait another hundred years, when William Huggins together with his wife Mary Huggins turned his spectroscope on various nebulae. Some, such as the Andromeda Nebula, had spectra quite similar to those of stars, but turned out to be galaxies consisting of hundreds of millions of individual stars. Others looked very different. Rather than a strong continuum with absorption lines superimposed, the Orion Nebula and other similar objects showed only a small number of emission lines.[8] In planetary nebulae, the brightest of these spectral lines was at a wavelength of 500.7 nanometres, which did not correspond with a line of any known chemical element. At first it was hypothesized that the line might be due to an unknown element, which was named nebulium—a similar idea had led to the discovery of helium through analysis of the Sun's spectrum in 1868.[9] However, while helium was isolated on earth soon after its discovery in the spectrum of the sun, nebulium was not. In the early 20th century, Henry Norris Russell proposed that rather than being a new element, the line at 500.7 nm was due to a familiar element in unfamiliar conditions.[10]

Interstellar matter, considered dense in an astronomical context, is at high vacuum by laboratory standards. Physicists showed in the 1920s that in gas at extremely low density, electrons can populate excited metastable energy levels in atoms and ions, which at higher densities are rapidly de-excited by collisions.[11] Electron transitions from these levels in doubly ionized oxygen give rise to the 500.7 nm line.[12] These spectral lines, which can only be seen in very low density gases, are called forbidden lines. Spectroscopic observations thus showed that planetary nebulae consisted largely of extremely rarefied ionised oxygen gas (OIII).

During the 20th century, observations showed that H II regions often contained hot, bright stars.[12] These stars are many times more massive than the Sun, and are the shortest-lived stars, with total lifetimes of only a few million years (compared to stars like the Sun, which live for several billion years). Therefore, it was surmised that H II regions must be regions in which new stars were forming.[12] Over a period of several million years, a cluster of stars will form in an H II region, before radiation pressure from the hot young stars causes the nebula to disperse.[13]

Origin and lifetime

[edit]

The precursor to an H II region is a giant molecular cloud (GMC). A GMC is a cold (10–20 K) and dense cloud consisting mostly of molecular hydrogen.[5] GMCs can exist in a stable state for long periods of time, but shock waves due to supernovae, collisions between clouds, and magnetic interactions can trigger its collapse. When this happens, via a process of collapse and fragmentation of the cloud, stars are born (see stellar evolution for a lengthier description).[13]

As stars are born within a GMC, the most massive will reach temperatures hot enough to ionise the surrounding gas.[5] Soon after the formation of an ionising radiation field, energetic photons create an ionisation front, which sweeps through the surrounding gas at supersonic speeds. At greater and greater distances from the ionising star, the ionisation front slows, while the pressure of the newly ionised gas causes the ionised volume to expand. Eventually, the ionisation front slows to subsonic speeds, and is overtaken by the shock front caused by the expansion of the material ejected from the nebula. The H II region has been born.[14]

The lifetime of an H II region is of the order of a few million years.[15] Radiation pressure from the hot young stars will eventually drive most of the gas away. In fact, the whole process tends to be very inefficient, with less than 10 percent of the gas in the H II region forming into stars before the rest is blown off.[13] Contributing to the loss of gas are the supernova explosions of the most massive stars, which will occur after only 1–2 million years.

Destruction of stellar nurseries

[edit]

Stars form in clumps of cool molecular gas that hide the nascent stars. It is only when the radiation pressure from a star drives away its 'cocoon' that it becomes visible. The hot, blue stars that are powerful enough to ionize significant amounts of hydrogen and form H II regions will do this quickly, and light up the region in which they just formed. The dense regions which contain younger or less massive still-forming stars and which have not yet blown away the material from which they are forming are often seen in silhouette against the rest of the ionised nebula. Bart Bok and E. F. Reilly searched astronomical photographs in the 1940s for "relatively small dark nebulae", following suggestions that stars might be formed from condensations in the interstellar medium; they found several such "approximately circular or oval dark objects of small size", which they referred to as "globules", since referred to as Bok globules.[16] Bok proposed at the December 1946 Harvard Observatory Centennial Symposia that these globules were likely sites of star formation.[17] It was confirmed in 1990 that they were indeed stellar birthplaces.[18] The hot young stars dissipate these globules, as the radiation from the stars powering the H II region drives the material away. In this sense, the stars which generate H II regions act to destroy stellar nurseries. In doing so, however, one last burst of star formation may be triggered, as radiation pressure and mechanical pressure from supernova may act to squeeze globules, thereby enhancing the density within them.[19]

The young stars in H II regions show evidence for containing planetary systems. The Hubble Space Telescope has revealed hundreds of protoplanetary disks (proplyds) in the Orion Nebula.[20] At least half the young stars in the Orion Nebula appear to be surrounded by disks of gas and dust,[21] thought to contain many times as much matter as would be needed to create a planetary system like the Solar System.

Characteristics

[edit]Physical properties

[edit]

H II regions vary greatly in their physical properties. They range in size from so-called ultra-compact (UCHII) regions perhaps only a light-year or less across, to giant H II regions several hundred light-years across.[5] Their size is also known as the Stromgren radius and essentially depends on the intensity of the source of ionising photons and the density of the region. Their densities range from over a million particles per cm3 in the ultra-compact H II regions to only a few particles per cm3 in the largest and most extended regions. This implies total masses between perhaps 100 and 105 solar masses.[22]

There are also "ultra-dense H II" regions (UDHII).[23]

Depending on the size of an H II region there may be several thousand stars within it. This makes H II regions more complicated than planetary nebulae, which have only one central ionising source. Typically H II regions reach temperatures of 10,000 K.[5] They are mostly ionised gases with weak magnetic fields with strengths of several nanoteslas.[24] Nevertheless, H II regions are almost always associated with a cold molecular gas, which originated from the same parent GMC.[5] Magnetic fields are produced by these weak moving electric charges in the ionised gas, suggesting that H II regions might contain electric fields.[25]

A number of H II regions also show signs of being permeated by a plasma with temperatures exceeding 10,000,000 K, sufficiently hot to emit X-rays. X-ray observatories such as Einstein and Chandra have noted diffuse X-ray emissions in a number of star-forming regions, notably the Orion Nebula, Messier 17, and the Carina Nebula.[27] The hot gas is likely supplied by the strong stellar winds from O-type stars, which may be heated by supersonic shock waves in the winds, through collisions between winds from different stars, or through colliding winds channeled by magnetic fields. This plasma will rapidly expand to fill available cavities in the molecular clouds due to the high speed of sound in the gas at this temperature. It will also leak out through holes in the periphery of the H II region, which appears to be happening in Messier 17.[28]

Chemically, H II regions consist of about 90% hydrogen. The strongest hydrogen emission line, the H-alpha line at 656.3 nm, gives H II regions their characteristic red colour. (This emission line comes from excited un-ionized hydrogen.) H-beta is also emitted, but at approximately 1/3 of the intensity of H-alpha. Most of the rest of an H II region consists of helium, with trace amounts of heavier elements. Across the galaxy, it is found that the amount of heavy elements in H II regions decreases with increasing distance from the galactic centre.[29] This is because over the lifetime of the galaxy, star formation rates have been greater in the denser central regions, resulting in greater enrichment of those regions of the interstellar medium with the products of nucleosynthesis.

Numbers and distribution

[edit]

H II regions are found only in spiral galaxies like the Milky Way and irregular galaxies. They are not seen in elliptical galaxies. In irregular galaxies, they may be dispersed throughout the galaxy, but in spirals they are most abundant within the spiral arms. A large spiral galaxy may contain thousands of H II regions.[22]

The reason H II regions rarely appear in elliptical galaxies is that ellipticals are believed to form through galaxy mergers.[30] In galaxy clusters, such mergers are frequent. When galaxies collide, individual stars almost never collide, but the GMCs and H II regions in the colliding galaxies are severely agitated.[30] Under these conditions, enormous bursts of star formation are triggered, so rapid that most of the gas is converted into stars rather than the normal rate of 10% or less.

Galaxies undergoing such rapid star formation are known as starburst galaxies. The post-merger elliptical galaxy has a very low gas content, and so H II regions can no longer form.[30] Twenty-first century observations have shown that a very small number of H II regions exist outside galaxies altogether. These intergalactic H II regions may be the remnants of tidal disruptions of small galaxies, and in some cases may represent a new generation of stars in a galaxy's most recently accreted gas.[31]

Morphology

[edit]H II regions come in an enormous variety of sizes. They are usually clumpy and inhomogeneous on all scales from the smallest to largest.[5] Each star within an H II region ionises a roughly spherical region—known as a Strömgren sphere—of the surrounding gas, but the combination of ionisation spheres of multiple stars within a H II region and the expansion of the heated nebula into surrounding gases creates sharp density gradients that result in complex shapes.[32] Supernova explosions may also sculpt H II regions. In some cases, the formation of a large star cluster within an H II region results in the region being hollowed out from within. This is the case for NGC 604, a giant H II region in the Triangulum Galaxy.[33] For a H II region which cannot be resolved, some information on the spatial structure (the electron density as a function of the distance from the center, and an estimate of the clumpiness) can be inferred by performing an inverse Laplace transform on the frequency spectrum.

Notable regions

[edit]

Notable Galactic H II regions include the Orion Nebula, the Eta Carinae Nebula, and the Berkeley 59 / Cepheus OB4 Complex.[34] The Orion Nebula, about 500 pc (1,500 light-years) from Earth, is part of OMC-1, a giant molecular cloud that, if visible, would be seen to fill most of the constellation of Orion.[12] The Horsehead Nebula and Barnard's Loop are two other illuminated parts of this cloud of gas.[35] The Orion Nebula is actually a thin layer of ionised gas on the outer border of the OMC-1 cloud. The stars in the Trapezium cluster, and especially θ1 Orionis, are responsible for this ionisation.[12]

The Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way at about 50 kpc (160 thousand light years), contains a giant H II region called the Tarantula Nebula. Measuring at about 200 pc (650 light years) across, this nebula is the most massive and the second-largest H II region in the Local Group.[36] It is much bigger than the Orion Nebula, and is forming thousands of stars, some with masses of over 100 times that of the sun—OB and Wolf-Rayet stars. If the Tarantula Nebula were as close to Earth as the Orion Nebula, it would shine about as brightly as the full moon in the night sky. The supernova SN 1987A occurred in the outskirts of the Tarantula Nebula.[32]

Another giant H II region—NGC 604 is located in M33 spiral galaxy, which is at 817 kpc (2.66 million light years). Measuring at approximately 240 × 250 pc (800 × 830 light years) across, NGC 604 is the second-most-massive H II region in the Local Group after the Tarantula Nebula, although it is slightly larger in size than the latter. It contains around 200 hot OB and Wolf-Rayet stars, which heat the gas inside it to millions of degrees, producing bright X-ray emissions. The total mass of the hot gas in NGC 604 is about 6,000 Solar masses.[33]

Current issues

[edit]

As with planetary nebulae, estimates of the abundance of elements in H II regions are subject to some uncertainty.[37] There are two different ways of determining the abundance of metals (metals in this case are elements other than hydrogen and helium) in nebulae, which rely on different types of spectral lines, and large discrepancies are sometimes seen between the results derived from the two methods.[36] Some astronomers put this down to the presence of small temperature fluctuations within H II regions; others claim that the discrepancies are too large to be explained by temperature effects, and hypothesise the existence of cold knots containing very little hydrogen to explain the observations.[37]

The full details of massive star formation within H II regions are not yet well known. Two major problems hamper research in this area. First, the distance from Earth to large H II regions is considerable, with the nearest H II (California Nebula) region at 300 pc (1,000 light-years);[38] other H II regions are several times that distance from Earth. Secondly, the formation of these stars is deeply obscured by dust, and visible light observations are impossible. Radio and infrared light can penetrate the dust, but the youngest stars may not emit much light at these wavelengths.[35]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ian Ridpath (2012). A Dictionary of Astronomy: H II region (2nd rev. ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199609055.001.0001. ISBN 9780199609055. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ "Bubbles of Brand New Stars". www.eso.org. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "Thermal Radio Emission from HII Regions". National Radio Astronomy Observatory (US). Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Harrison, T.G. (1984). "The Orion Nebula—where in History is it". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 25: 65–79. Bibcode:1984QJRAS..25...65H.

- ^ a b c d e f g Anderson, L.D.; Bania, T.M.; Jackson, J.M.; et al. (2009). "The molecular properties of galactic HII regions". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 181 (1): 255–271. arXiv:0810.3685. Bibcode:2009ApJS..181..255A. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/181/1/255. S2CID 10641857.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth Glyn (1991). Messier's nebulae and star clusters. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-521-37079-0.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (2012). "Diffuse nebula". A Dictionary of Astronomy. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199609055.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-960905-5.

- ^ Huggins, W.; Miller, W.A. (1864). "On the Spectra of some of the Nebulae". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 154: 437–444. Bibcode:1864RSPT..154..437H. doi:10.1098/rstl.1864.0013.

- ^ Tennyson, Jonathan (2005). Astronomical spectroscopy: an introduction to the atomic and molecular physics of astronomical spectra. Imperial College Press. pp. 99–102. ISBN 978-1-86094-513-7.

- ^ Russell, H.N.; Dugan, R.S.; Stewart, J.Q (1927). Astronomy II Astrophysics and Stellar Astronomy. Boston: Ginn & Co. p. 837.

- ^ Bowen, I.S. (1928). "The origin of the nebular lines and the structure of the planetary nebulae". Astrophysical Journal. 67: 1–15. Bibcode:1928ApJ....67....1B. doi:10.1086/143091.

- ^ a b c d e O'Dell, C.R. (2001). "The Orion Nebula and its associated population" (PDF). Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 39 (1): 99–136. Bibcode:2001ARA&A..39...99O. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.39.1.99.

- ^ a b c Pudritz, Ralph E. (2002). "Clustered Star Formation and the Origin of Stellar Masses". Science. 295 (5552): 68–75. Bibcode:2002Sci...295...68P. doi:10.1126/science.1068298. PMID 11778037. S2CID 33585808.

- ^ Franco, J.; Tenorio-Tagle, G.; Bodenheimer, P. (1990). "On the formation and expansion of H II regions". Astrophysical Journal. 349: 126–140. Bibcode:1990ApJ...349..126F. doi:10.1086/168300.

- ^ Alvarez, M.A.; Bromm, V.; Shapiro, P.R. (2006). "The H II Region of the First Star". Astrophysical Journal. 639 (2): 621–632. arXiv:astro-ph/0507684. Bibcode:2006ApJ...639..621A. doi:10.1086/499578. S2CID 12753436.

- ^ Bok, Bart J.; Reilly, Edith F. (1947). "Small Dark Nebulae". Astrophysical Journal. 105: 255–257. Bibcode:1947ApJ...105..255B. doi:10.1086/144901.

- ^ Bok, Bart J. (1948). "Dimension and Masses of Dark Nebulae". Harvard Observatory Monographs. 7 (7): 53–72. Bibcode:1948HarMo...7...53B.

- ^ Yun, J.L.; Clemens, D.P. (1990). "Star formation in small globules – Bart Bok was correct". Astrophysical Journal. 365: 73–76. Bibcode:1990ApJ...365L..73Y. doi:10.1086/185891.

- ^ Stahler, S.; Palla, F. (2004). The Formation of Stars. Wiley VCH. doi:10.1002/9783527618675. ISBN 978-3-527-61867-5.

- ^ Ricci, L.; Robberto, M.; Soderblom, D. R. (2008). "The Hubble Space Telescope/advanced Camera for Surveys Atlas of Protoplanetary Disks in the Great Orion Nebula". Astronomical Journal. 136 (5): 2136–2151. Bibcode:2008AJ....136.2136R. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/136/5/2136.

- ^ O'dell, C. R.; Wen, Zheng (1994). "Post refurbishment mission Hubble Space Telescope images of the core of the Orion Nebula: Proplyds, Herbig-Haro objects, and measurements of a circumstellar disk". Astrophysical Journal. 436 (1): 194–202. Bibcode:1994ApJ...436..194O. doi:10.1086/174892.

- ^ a b Flynn, Chris (2005). "Lecture 4B: Radiation case studies (HII regions)". Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- ^ Kobulnicky, Henry A.; Johnson, Kelsey E. (1999). "Signatures of the Youngest Starbursts: Optically Thick Thermal Bremsstrahlung Radio Sources in Henize 2–10". Astrophysical Journal. 527 (1): 154–166. arXiv:astro-ph/9907233. Bibcode:1999ApJ...527..154K. doi:10.1086/308075. S2CID 15431678.

- ^ Heiles, C.; Chu, Y.-H.; Troland, T.H. (1981). "Magnetic field strengths in the HII regions S117, S119, and S264". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 247: L77 – L80. Bibcode:1981ApJ...247L..77H. doi:10.1086/183593.

- ^ Carlqvist, P; Kristen, H.; Gahm, G.F. (1998). "Helical structures in a Rosette elephant trunk". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 332: L5 – L8. Bibcode:1998A&A...332L...5C.

- ^ "Into the storm". www.spacetelescope.org. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Townsley, L. K.; et al. (2011). "The Chandra Carina Complex Project: Deciphering the Enigma of Carina's Diffuse X-ray Emission". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement. 194 (1): 15. arXiv:1103.0764. Bibcode:2011ApJS..194...15T. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/194/1/15. S2CID 40973448.

- ^ Townsley, L. K.; et al. (2003). "10 MK Gas in M17 and the Rosette Nebula: X-Ray Flows in Galactic H II Regions". The Astrophysical Journal. 593 (2): 874–905. arXiv:astro-ph/0305133. Bibcode:2003ApJ...593..874T. doi:10.1086/376692. S2CID 16188805.

- ^ Shaver, P. A.; McGee, R. X.; Newton, L. M.; Danks, A. C.; Pottasch, S. R. (1983). "The galactic abundance gradient". MNRAS. 204: 53–112. Bibcode:1983MNRAS.204...53S. doi:10.1093/mnras/204.1.53.

- ^ a b c Hau, George K. T.; Bower, Richard G.; Kilborn, Virginia; et al. (2008). "Is NGC 3108 transforming itself from an early- to late-type galaxy – an astronomical hermaphrodite?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 385 (4): 1965–72. arXiv:0711.3232. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.385.1965H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12740.x. S2CID 17892515.

- ^ Oosterloo, T.; Morganti, R.; Sadler, E. M.; Ferguson, A.; van der Hulst, J.M.; Jerjen, H. (2004). P.-A. Duc; J. Braine; E. Brinks (eds.). Tidal Remnants and Intergalactic HII Regions. International Astronomical Union Symposium. Vol. 217. Astronomical Society of the Pacific. p. 486. arXiv:astro-ph/0310632. Bibcode:2004IAUS..217..486O. doi:10.1017/S0074180900198249.

- ^ a b Townsley, Leisa K.; Broos, Patrick S.; Feigelson, Eric D.; et al. (2008). "A Chandra ACIS Study of 30 Doradus. I. Superbubbles and Supernova Remnants". The Astronomical Journal. 131 (4): 2140–2163. arXiv:astro-ph/0601105. Bibcode:2006AJ....131.2140T. doi:10.1086/500532. S2CID 17417168.

- ^ a b Tullmann, Ralph; Gaetz, Terrance J.; Plucinsky, Paul P.; et al. (2008). "The chandra ACIS survey of M33 (ChASeM33): investigating the hot ionized medium in NGC 604". The Astrophysical Journal. 685 (2): 919–932. arXiv:0806.1527. Bibcode:2008ApJ...685..919T. doi:10.1086/591019. S2CID 1428019.

- ^ Majaess, D. J.; Turner, D.; Lane, D.; Moncrieff, K. (2008). "The Exciting Star of the Berkeley 59/Cepheus OB4 Complex and Other Chance Variable Star Discoveries". The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers. 36 (1): 90. arXiv:0801.3749. Bibcode:2008JAVSO..36...90M.

- ^ a b

- Ward-Thompson, D.; Nutter, D.; Bontemps, S.; et al. (2006). "SCUBA observations of the Horsehead nebula – what did the horse swallow?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 369 (3): 1201–1210. arXiv:astro-ph/0603604. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.369.1201W. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10356.x. S2CID 408726.

- Heiles, Carl; Haffner, L. M.; Reynolds, R. J.; Tufte, S. L. (2000). "Physical conditions, grain temperatures, and enhanced very small grains in Barnard's loop". The Astrophysical Journal. 536 (1): 335–. arXiv:astro-ph/0001024. Bibcode:2000ApJ...536..335H. doi:10.1086/308935. S2CID 14067314.

- ^ a b Lebouteiller, V.; Bernard-Salas, J.; Plucinsky, Brandl B.; et al. (2008). "Chemical composition and mixing in giant H II regions: NGC 3603, Doradus 30, and N66". The Astrophysical Journal. 680 (1): 398–419. arXiv:0710.4549. Bibcode:2008ApJ...680..398L. doi:10.1086/587503. S2CID 16924851.

- ^ a b Tsamis, Y.G.; Barlow, M.J.; Liu, X-W.; et al. (2003). "Heavy elements in Galactic and Magellanic Cloud H II regions: recombination-line versus forbidden-line abundances". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 338 (3): 687–710. arXiv:astro-ph/0209534. Bibcode:2003MNRAS.338..687T. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2003.06081.x. S2CID 18253949.

- ^ Straizys, V.; Cernis, K.; Bartasiute, S. (2001). "Interstellar extinction in the California Nebula region" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 374 (1): 288–293. Bibcode:2001A&A...374..288S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010689.

External links

[edit]- Hubble images of nebulae including several H II regions

- Information from SEDS

- Harvard astronomy course notes on H II regions