Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

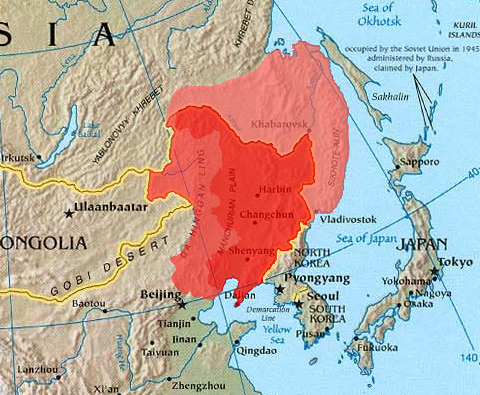

Outer Manchuria

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| History of Manchuria |

|---|

|

Outer Manchuria,[3][4][1][2][5] sometimes called Russian Manchuria, refers to a region in Northeast Asia that is now part of the Russian Far East[1] but historically formed part of Manchuria (until the mid-19th century). While Manchuria now more normatively refers to Northeast China, it originally included areas consisting of Priamurye between the left bank of Amur River and the Stanovoy Range to the north, and Primorskaya which covered the area in the right bank of both Ussuri River and the lower Amur River to the Pacific Coast. The region was ruled by a series of Chinese dynasties and the Mongol Empire, but control of the area was ceded to the Russian Empire by Qing China during the Amur Annexation in the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and 1860 Treaty of Peking,[6] with the terms "Outer Manchuria" and "Russian Manchuria" arising after the Russian annexation.

Prior to its annexation by Russia, Outer Manchuria was predominantly inhabited by various Tungusic peoples who were categorized by the Han Chinese as "Wild Jurchens". The Evenks,[1] who speak a closely related Tungusic language to Manchu, make up a significant part of the indigenous population today. When the region was a part of the Qing dynasty, a small population of Han Chinese men migrated to Outer Manchuria and married the local Tungusic women. Their mixed descendants would emerge as a distinct ethnic group known as the Taz people.

Etymology

[edit]"Manchuria" was coined in the 19th century to refer to the northeastern part of the Qing Empire, the traditional homeland of the Manchu people. After the Amur Annexation by the Russian Empire, the ceded areas were known as "Outer Manchuria" or "Russian Manchuria".[1][7][8][9][10][11][better source needed] (Russian: Приаму́рье, romanized: Priamurye;[note 1] simplified Chinese: 外满洲; traditional Chinese: 外滿洲; pinyin: Wài Mǎnzhōu or simplified Chinese: 外东北; traditional Chinese: 外東北; pinyin: Wài Dōngběi; lit. 'outer northeast').

History

[edit]Outer Manchuria comprises the modern-day Russian areas of Primorsky Krai, southern Khabarovsk Krai, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, the Amur Oblast and the island of Sakhalin.[9][12]: 338 (map)

In the 7th century, the Tang dynasty built administrative and military outposts on the Amur and in Suchan. The region was later controlled by the Parhae, a Korean-Manchu polity, during which time Korean communities were established in the region.[13]

The northern part of the area was disputed by Qing China and the Russian Empire, in the midst of the Russia's Far East expansion, between 1643 and 1689. The Treaty of Nerchinsk signed in 1689 after a series of conflicts, defined the Sino–Russian border as the Stanovoy Mountains and the Argun River. When the Qing sent officials to erect boundary markers, the markers were set up far to the south of the agreed limits, ignoring some 23,000 square miles of territory.[12]: 38

In 1809, the Japanese government sent explorer Mamiya Rinzō to Sakhalin and the region of the Amur to determine the extent of Russian influence and penetration.[12]: 334

Chang estimates that there were ten thousand Chinese and four to five thousand Koreans in the region during the 19th century. There might have been more than this number as well. The Qing had sent many of its political prisoners and criminals to exile in Manchuria beginning in 1644. This included all of the ethnic groups in China including Koreans.[14] Perhaps, the Han dynasties prior to the Qing did so as well.[13]: 74–77 [15]

To preserve the Manchu character of Manchuria, the Qing dynasty discouraged Han Chinese settlement in Manchuria; nevertheless, there was significant Han Chinese migration into areas south of the Amur and west of the Ussuri.[12]: 332 By the mid-19th century, there were very few subjects of the Qing Empire living in the areas north of the Amur and east of the Ussuri,[12]: 333 and Qing authority in the area was seen as tenuous by the Russians.[12]: 336 Despite warnings, Qing authorities remained indecisive about how to respond to the Russian presence.[12]: 338–339 In 1856, the Russian military entered the area north of the Amur on a pretext of defending the area from France and the UK;[12]: 341 Russian settlers founded new towns and cut down forests in the region,[12]: 341 and the Russian government created a new maritime province, Primorskaya Oblast, including Sakhalin, the mouth of the Amur, and Kamchatka with its capital at Nikolayevsk-on-Amur.[12]: 341 After losing the Opium Wars, Qing China was forced to sign a series of treaties that gave away territories and ports to various Western powers as well as to Russia and Japan; these were collectively known by the Chinese side[16] as the Unequal Treaties. Starting with the Treaty of Aigun in 1858 and, in the wake of the Second Opium War, the Treaty of Peking in 1860, the Sino–Russian border was realigned in Russia's favour along the Amur and Ussuri rivers. As a result, China lost the region[12]: 348 that came to be known as Outer Manchuria or Russian Manchuria (an area of 350,000 square miles (910,000 km2)[2]) and access to the Sea of Japan.[17][18][19] In the wake of these events, the Qing government changed course and encouraged Han Chinese migration to Manchuria (Chuang Guandong).[1][12]: 348

After 1860, Russian historians began to intentionally erase the histories and contributions of the Chinese and Koreans to the Russian Far East.[13]: 73–75 [20] The Russian historian, Semyon D. Anosov wrote, “In the 17th century, the Manchu-Tungus tribes living in the region were conquered by China and deported. Since then, the region has been deserted.”[21] Kim Syn Khva, a Soviet Korean historian and author of Essays on the History of the Soviet Koreans [очерки по историй Советских корейтсев], wrote, "The first Korean migrants appeared in the southern Ussuri region when secretly 13 families came here fleeing Korea from unbearable poverty and famine" in 1863.[22] However, the historian, Jon K. Chang found Western sources, most notably Ernst G. Ravenstein's The Russians on the Amur and J.M. Tronson's Personal Narrative of a Voyage to Japan, Kamtschatka, Siberia, Tartary, and Various Parts of Coast of China: In H.M.S. Barracouta,[23] which detailed Chinese, Korean and Manchu settlements from Ternei to Vladivostok and Poset before 1863 (see small map below).

Both Ravenstein (1856-60) and Tronson (1854-56) explored the Russian Far East before 1860. Ravenstein's account notes the differences between Koreans and Chinese versus the Manchus in the region. The former prepared and sold trepangs according to Ravenstein. They (Chinese and Koreans) also raised crops and cattle and lived in small villages and settlements among their co-ethnics. Ravenstein was a German geographer, cartographer and ethnographer of some note. Tronson's account called all of the East Asians whether Chinese, Korean, Manchu or Tungusic peoples "Mantchu-Tartars." Chang also interviewed an elderly Soviet Korean grandmother in 2008, named Soon-Ok Li. Ms. Li stated that, "No one came from Korea. We have always lived in Vondo [the Korean name for the Russian Far East]. Even my grandparents [Ms. Li was born in 1928] were born here."[13]

Modern opinions

[edit]In Russia

[edit]In 2016, Victor L. Larin, the director of the Institute of History, Archaeology and Ethnography of the Peoples of the Far East in Vladivostok, said that the fact that Russia had built Vladivostok "is a historical fact that cannot be rewritten", and that the notion that Vladivostok was ever a Chinese town is a "myth" based on a misreading of evidence that a few Chinese sometimes came to the area to fish and collect sea cucumbers.[24] The main point of Viktor Larin was that the "Russian Far East (outer Manchuria) is Russia's. They developed the region and thus, will not give it back."[citation needed]

Sergey Radchenko, a professor at Johns Hopkins SAIS known for his writings on Sino-Russian relations,[25] stated, "China fully recognizes Russia's sovereignty over these territories" (referring to the Russian Far East). He also called Taiwan's President Lai "seriously misguided" for attempting to suggest to China to take back her "lost territories", rather than invade Taiwan.[26] On 3 September 2024 Maria Zakharova, the spokesperson for the Russian Foreign Ministry, said that "the mutual renunciation of territorial claims by Moscow and Beijing had been enshrined in the July 16, 2001, Treaty of Good Neighborliness, Friendship and Cooperation, with Moscow and Beijing putting border issues to bed once and for all by signing the Additional Agreement on the Eastern part of the Russia-China Border on October 14, 2004, and ratifying the document later. This position was confirmed in a number of other joint documents that China and Russia adopted at various levels, including at the highest one."[27]

In the West

[edit]Despite the potential for territorial claims coextensive with the Qing dynasty, Chinese leaders as of 2014 had not suggested that Mongolia and part of Outer or Russian Manchuria would be a legitimate objective.[10] In April 2023, US diplomat John Bolton speculated that China is "undoubtedly eyeing this vast territory, which potentially contains incalculable mineral wealth", referring to Asian Russia generally, further noting that "[s]ignificant portions of this region were under Chinese sovereignty until the 1860 Treaty of Peking".[5] However, two American historians, Jon K. Chang and Bruce A. Elleman, disagree with Larin, Radchenko and other Russian historians. Chang and Elleman note that in 1919 and 1920, Lev M. Karakhan, the Soviet deputy minister (also called "commissar") of foreign affairs, issued two legally binding "declarations" called the Karakhan Manifestos in which he promised to return to China all territories taken in Siberia and Manchuria during the Tsarist period and to return the Chinese Eastern Railway and other concessions. He signed his name on both documents as deputy minister of foreign affairs. To date, China has never renounced the offer of the two Karakhan Manifestos. During 1991 and 2004, there were border-treaties between Russia and China. The Karakhan Manifestos are not border treaties. They are unilateral, but legally binding offers of the return of territory to China.[28][29] Here are three excerpts from the first Karakhan Manifesto (I) according to the translated, English version published by Allen S. Whiting:

We bring help not only to our own labouring classes, but to the Chinese people too, and we once more remind them of what they have been told ever since the great October revolution of 1917, but which was perhaps concealed from them by the venal press of America, Europe, and Japan. ...

But the Chinese people, the Chinese workers and peasants, could not even learn the truth, could not find out the reason for this invasion by the American, European, and Japanese robbers of Manchuria and Siberia. ...

The Soviet Government has renounced the conquests made by the Tsarist Government which deprived China of Manchuria and other areas. ... The Soviet Government is well aware ... that the return to the Chinese people of what was taken from them requires first of all putting an end to the robber invasion of Manchuria and Siberia. The Karakhan Manifestos I and II are similar. Both promise to return "the conquests made by the Tsarist Government which deprived China of Manchuria and other areas."

— Whiting, Soviet Policies, pp. 269–271[30]

Place names

[edit]Today, there are reminders of the ancient Manchu domination in English-language toponyms: for example, the Sikhote-Alin, the great coastal range; the Khanka Lake; the Amur and Ussuri rivers; the Greater Khingan, Lesser Khingan and other small mountain ranges; and the Shantar Islands.

In 1973, the Soviet Union renamed several locations in the region that bore names of Chinese origin. Names affected included Partizansk for Suchan; Dalnegorsk for Tetyukhe; Rudnaya Pristan for Tetyukhe‐Pristan; Dalnerechensk for Iman; Sibirtsevo for Mankovka; Gurskoye for Khungari; Cherenshany for Sinan cha; Rudny for Lifudzin; and Uglekamensk for Severny Suchan.[16][31]

On 14 February 2023, the Ministry of Natural Resources of the People's Republic of China relabelled eight cities and areas inside Russia in the region with Chinese names.[32][33] The eight names are Boli for Khabarovsk, Hailanpao for Blagoveshchensk, Haishenwai (Haishenwei) for Vladivostok, Kuye for Sakhalin, Miaojie for Nikolayevsk-on-Amur, Nibuchu for Nerchinsk, Outer Khingan (Outer Xing'an[34]) for Stanovoy Range, and Shuangchengzi for Ussuriysk.[35]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Now Priamurye usually refers to a narrower region of Amur Oblast and parts of Khabarovsk Krai.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Schneider, Julia C. (2017). "The New Setting: Political Thinking after 1912". Nation and Ethnicity: Chinese Discourses on History,. p. 277. ISBN 978-90-04-33011-5. ISSN 1574-4493. OCLC 974211957.

In the mid-19th century, the Qing government gave over (so-called) Outer Manchuria, where mostly non-Manchu Tungusic people dwelled, to the Russian Empire by the Treaty of Aigun (Aigun tiaoyue, 1858) and the (First) Convention of Peking (Beijing tiaoyue, 1860). ... The Convention of Peking, one of several unequal treaties, moreover assigned the parts in the East of the Ussuri River (Wusulijiang) to Russia. Outer Manchuria, also called Russian Manchuria was never claimed to be part of a Chinese nation-state. Today it belongs to the Russian Federation, is no longer referred to as Outer Manchuria, and is considered to be part of Siberia. Consequently, the name Manchuria refers only to Inner Manchuria today. In the following, I will refer to Inner Manchuria as Manchuria.

- ^ a b c Kissinger, Henry (2011). "From Preeminence to Decline". On China. New York: Penguin Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-59420-271-1. LCCN 2011009265. OCLC 1025648355.

For these services Moscow exacted a staggering territorial price: a broad swath of territory in so-called Outer Manchuria along the Pacific coast, including the port city now called Vladivostok. In a stroke, Russia had gained a major new naval base, a foothold in the Sea of Japan, and 350,000 square miles of territory once considered Chinese.

- ^ Shurtleff, William (2022). History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Manchuria (1833–2022). Soyinfo Center. p. 6. ISBN 9781948436670.

- ^ Shi, David (2023). Spirit Voices: The Mysteries and Magic of North Asian Shamanism. Red Wheel Weiser. p. 140. ISBN 9781633412835.

- ^ a b Bolton, John (12 April 2023). "A New American Grand Strategy to Counter Russia and China". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. OCLC 781541372. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023.

New Russian leaders may or may not look to the West rather than Beijing, and might be so weak that the Russian Federation's fragmentation, especially east of the Urals, isn't inconceivable. Beijing is undoubtedly eyeing this vast territory, which potentially contains incalculable mineral wealth. Significant portions of this region were under Chinese sovereignty until the 1860 Treaty of Peking transferred 'outer Manchuria', including extensive Pacific coast lands, to Moscow.

- ^ O'Hanlon, Michael E. (2015). "Conflicts Real, Latent, and Imaginable". The Future of Land Warfare. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-081572689-0. OCLC 930512519.

- ^ "SAGHALIN, or SAKHALIN". The Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XXI (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1886. p. 147.

- ^ "Manchuria". The New International Encyclopaedia. Vol. XII. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. 1906. p. 782. "MANCHURIA, man-cho͞oʹre-a (the land of the Manchus). The northeastern part of the Chinese Empire, situated east of Mongolia and the Argun River (which formerly traversed Manchurian territory), south of the Amur River (which separates it from Siberia), and west of the Usuri, which separates it from Primorsk (Maritime Province) or Russian Manchuria (a Chinese possession until 1860)."

- ^ a b "Amoor, Territory of". A Complete Pronouncing Gazetteer or Geographical Dictionary of the World (new revised ed.). Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company. 1898. p. 489. OCLC 83607338.

Amoor, Territory of, a name applied to Russian Manchooria, or the region of Southeastern Siberia acquired from the Chinese and Japanese by the Russians since 1858. It is bounded on the N. by Siberia proper, on the E. by the Seas of Okhotsk and Japan, the coast being Russian as far S. as the river Toomen, which divides it from Corea (the island of Saghalin being now included); on the W. by Chinese Manchooria, the rivers Oosooree, Argoon, Soongaree, and Amoor forming (for the most part) the boundary; and on the N.W. by the government of Transbaikalia. Its area, 905,462 square miles, is over four times that of France. It is divided into the provinces of Amoor and Primorsk.

- ^ a b Steinberg, James; O'Hanlon, Michael E. (2014). "The Determinants of Chinese Strategy". Strategic Reassurance and Resolve: U.S.-China Relations in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-691-15951-5. LCCN 2013035849. OCLC 861542585.

- ^ Callahan, William A. (2010). China: The Pessoptimist Nation. Oxford University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-19-960439-5. OCLC 754167885.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fletcher, Joseph (1978). "Sino-Russian Relations, 1800–62: The loss of north-east Manchuria". In Fairbank, John K. (ed.). The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 10. Cambridge University Press. pp. 38, 332–351.

- ^ a b c d Jon K. Chang (1 January 2025), "Battling for Equality: East Asians in Imperial and Soviet Russia and the Soviet Chinese Deportation of 1937–39", Region: Regional Studies of Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, Vol. 14:1, 14 (1): 69–104, doi:10.1353/reg.2025.a971386

- ^ Lee, Robert H.G. (1970). The Manchurian Frontier in Ch'ing History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 3–40.

- ^ Ernst G. Ravenstein (1 January 1861), The Russians on the Amur: Its Discovery Conquest and Civilisation, London: Trubner & Co., pp. 227–229, 230–231

- ^ a b "China Assails New Siberia Names". The New York Times. 8 March 1973. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023.

- ^ An, Tai Sung (1973). The Sino-Soviet Territorial Dispute. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. pp. 31–38. ISBN 0664209556.

- ^ Stephan, John J. (1994). The Russian Far East: A History. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 14–32. ISBN 0804727015.

- ^ Miller, Chris (2021). We Shall Be Masters: Russian Pivots to East Asia from Peter the Great to Putin. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 52–83. ISBN 9780674259331.

- ^ John J. Stephan (1 January 1994), The Russian Far East: A History, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 7–19, 40–50, ISBN 978-0-8047-2701-3

- ^ : 73–74

- ^ Kim, Syn Khva (1965). Ocherki po istorii Sovetskikh koreitsev. Alma-Ata: Nauka. p. 28.

- ^ J.M. Tronson (1 January 1859), Personal Narrative of a Voyage to Japan, Kamtschatka, Siberia, Tartary, and Various Parts of Coast of China: In H.M.S. Barracouta, London: Smith, Elder & Co., pp. 375–377

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (23 July 2016). "Vladivostok Lures Chinese Tourists (Many Think It's Theirs)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016.

- ^ "Sergey Radchenko". Johns Hopkins SAIS. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2025.

- ^ McCartney, Micah (2 September 2024). "Taiwan Turns Tables on China With Russian Territories Jibe". Newsweek.

- ^ "Russia, China officially confirm rununciation of territorial claims". TASS. 3 September 2024.

- ^ Chang, Jon K.; Elleman, Bruce A. (11 September 2024). "Beijing's claims to Russian territory". Taipei Times.

- ^ Chang, Jon K.; Elleman, Bruce A. (18 September 2024). "Russian far east belongs to China". Taipei Times.

- ^ Whiting, Allen S. (1953). Soviet Policies in China, 1917–1924. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804706124.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "NCNA Condemns New Soviet Place Names in Far East". Daily Report: People's Republic of China. I (45). Foreign Broadcast Information Service: A 1. 7 March 1973. ISSN 0892-0141. OCLC 1113433.

- ^ Pao, Jeff (25 February 2023). "China's ironic reticence on land grab in Ukraine". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023.

- ^ Jan van der Made (21 March 2023). "Territorial dispute between China and Russia risks clouding friendly future". Radio France Internationale. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023.

- ^ Nahaylo, Bohdan (26 February 2023). "OPINION: China Challenges Russia by Restoring Chinese Names of Cities on Their Border". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023.

- ^ "公开地图内容表示规范". Ministry of Natural Resources of the People's Republic of China (in Simplified Chinese). 2023. p. 7. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023.

External links

[edit]- Karaoğlu, Semiha. "The Legacy of a War: How the Legacy of the Russo-Japanese War Affected the US-Japan Relations". researchgate. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022.

- Books.google.com: Russia in Manchuria — 1903 illustrated article.

Outer Manchuria

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Geography

Geographical Extent and Boundaries

Outer Manchuria comprises the territories in the Russian Far East ceded by the Qing dynasty to the Russian Empire through the Treaty of Aigun on May 16, 1858, and the Treaty of Peking on November 14, 1860.[3][9] The Treaty of Aigun established Russian control over all lands north of the Amur River, from its confluence with the Argun River eastward to the Ussuri River.[3][10] This cession included the left bank of the Amur, significantly expanding Russian territory in Siberia by securing the river as the boundary.[10] The Treaty of Peking confirmed the Amur boundary and further delimited the eastern extent by ceding to Russia the lands between the Ussuri River and the Pacific Ocean, including access to the Sea of Japan.[9][11] This added approximately 400,000 square kilometers east of the Ussuri, completing the southern and western boundaries along these rivers from the Argun-Shilka confluence downstream via the Amur to the Ussuri, then to the sea.[11] The northern boundary follows the Stanovoy Mountains, as referenced in earlier delimitations like the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk, though adjusted by the later treaties.[9] In contemporary terms, the region's boundaries align with the international border between Russia and China, with minor adjustments finalized in 2008 when Russia transferred 173 square kilometers of disputed islands in the Amur and Ussuri rivers to China, including parts of Bolshoy Ussuriysky Island.[6] Geographically, Outer Manchuria spans from the Stanovoy Range in the north to the Amur and Ussuri rivers in the south and west, and to the Sea of Japan in the east, encompassing diverse terrain including taiga forests, river valleys, and coastal plains.[12]Etymology and Terminology

The term "Manchuria" derives from the name of the Manchu people, whose ethnonym Manchu (or Manju in Manchu script) literally means "pure" or "true," referring to their self-perceived descent from the Jurchen tribes.[13] This regional exonym emerged in European cartography and literature through 18th-century romanizations of Manchu terms, possibly influenced by Dutch, Russian, or French sources, and was later popularized by the Japanese designation Manshū during their late-19th-century expansionist interests in the area.[14] [15] The name does not correspond to any indigenous toponym used by local Tungusic, Mongol, or Han populations, who historically referred to parts of the region by riverine or tribal names such as the Amur (Heilong in Chinese) or Ussuri basins. "Outer Manchuria" specifically designates the territories ceded by the Qing Empire to Russia—encompassing approximately 1 million square kilometers north of the Amur River, east of the Ussuri River, and including Sakhalin Island—via the Treaty of Aigun on May 16, 1858, and the Treaty of Peking on November 14, 1860.[16] The prefix "outer" contrasts these areas with "Inner Manchuria," the core Manchu homeland retained under Chinese control, reflecting a post-cession geographical distinction rather than a pre-19th-century native usage. In Russian imperial and Soviet administration, the region was termed Priamurye (Приаму́рье), denoting "Amur-adjacent lands," emphasizing its fluvial boundaries over ethnic connotations.[1] The English compound "Outer Manchuria" gained traction in 20th-century Western scholarship to describe these Russian Far East provinces, including modern Amur Oblast, Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Khabarovsk Krai, Primorsky Krai, and parts of Zabaykalsky Krai, though Chinese sources more commonly employ Wài Dōngběi ("Outer Northeast") to frame it within a narrative of territorial loss.[17]Historical Development

Indigenous Peoples and Pre-Qing Era

The territories comprising Outer Manchuria were primarily inhabited by Tungusic-speaking indigenous peoples, such as the Nanai, Ulchi, Udege, Oroch, Evenki, Negidal, and Oroqen, who maintained traditional lifestyles centered on hunting, fishing, gathering, and, in northern areas, reindeer herding.[18][19] These groups, distributed along the Amur River basin and its tributaries, formed small, semi-nomadic communities adapted to the region's taiga and riverine environments, with archaeological and genetic evidence indicating their presence for millennia prior to significant external influences.[20] Jurchen tribes, also Tungusic, occupied parts of the area, particularly in the east, and were known to Chinese chroniclers as "Wild Jurchens" distinct from southern counterparts.[21] Prior to the 17th century, these indigenous populations experienced sporadic interactions with neighboring powers but lacked centralized governance. The Ming Dynasty exerted nominal authority through expeditions and tribute systems, notably establishing the Nurgan Regional Military Commission in 1409 at the Amur River's mouth to oversee Jurchen and Tungusic guards, though permanent control was limited and the commission was dismantled by the 1430s amid logistical challenges and internal Ming priorities. Local tribes, including Tungusic groups under Ming categorization as "Guards," paid intermittent tribute—such as furs and horses—but maintained autonomy, with no evidence of widespread Han settlement or agricultural transformation in the region.[20] This era reflected a landscape of tribal confederations rather than state administration, shaped by environmental constraints and mobility.[22]Qing Dynasty Control and Conflicts

The Qing dynasty, established by the Manchu conquest of the Ming in 1644, asserted firm control over Manchuria as its ethnic homeland, integrating the region into a system of military-administrative divisions known as the Eight Banners. Bannermen garrisons were stationed at strategic points, including along the Amur River basin, to enforce authority over indigenous Tungusic peoples such as the Daur and Evenks, who were incorporated via tribute relations rather than direct settlement.[23] This structure maintained sparse but effective oversight, with Manchu nobles administering vast tracts through a network of generals (jiangjun) responsible for border defense and tax collection.[23] To preserve Manchu cultural and demographic dominance and prevent Han assimilation, the Qing imposed stringent bans on civilian Han migration into Manchuria starting in the mid-17th century, reversing earlier encouragements of settlement. These restrictions were physically demarcated by the Willow Palisade, a wooden barrier system of felled trees and ditches constructed between 1615 and the 1830s, stretching approximately 1,000 to 1,500 kilometers from the Amur to the Liao River, with gates for controlled access.[24] Enforcement involved patrols and penalties, though smuggling and gradual loosening occurred due to famines and overpopulation in China proper; by the Qianlong era (1735–1796), limited Han refugee influx was tolerated, but core Manchu lands remained restricted until the mid-19th century.[24][25] Border conflicts with Tsarist Russia emerged in the mid-17th century as Cossack explorers, seeking furs, penetrated the Amur region; Yerofey Khabarov's 1649–1653 expedition clashed with local tribes under Qing suzerainty, prompting initial Manchu countermeasures. Escalation occurred with Russian construction of Albazin fort in the 1650s–1660s, leading to skirmishes over tribute rights and territory. The Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661–1722) responded decisively, dispatching expeditions in 1684–1686; the first siege of Albazin in 1685 involved a Qing force of up to 15,000 against 450–800 Russians, employing artillery and entrenchments, while the 1686 siege forced a Russian capitulation after heavy bombardment and starvation.[26][26] These victories checked Russian advances, culminating in the Treaty of Nerchinsk on August 27, 1689, which delineated the border along the Argun River and Stanovoy Mountains, awarded Qing the Amur basin (including Outer Manchuria), mandated Russian fort dismantlement, and opened limited trade—marking the Qing's only pre-19th-century diplomatic equality with a European power.[27][28] Qing control persisted through the 18th century, bolstered by the 1727 Treaty of Kyakhta, which refined borders west of Outer Manchuria and regulated trade caravans, amid minimal incursions due to mutual wariness and Qing military prestige. However, by the 1850s, internal crises—the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), which mobilized over 20 million combatants and devastated northern resources, and the Second Opium War (1856–1860)—eroded Qing capacity for frontier defense, leaving garrisons understrength and logistics strained. Russian Governor-General Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky exploited this, dispatching gunboat flotillas and troops to occupy Amur islands and build forts unopposed from 1854–1858, facing no significant Qing resistance beyond protests.[16][20] The resulting Treaty of Aigun, signed May 16, 1858, under duress by Qing envoy Yishan, ceded approximately 600,000 square kilometers north of the Amur to Russia without compensation, establishing the river as the boundary and reflecting the dynasty's fiscal-military exhaustion rather than battlefield defeat.[3][29] This opportunistic expansion, confirmed by the 1860 Treaty of Peking, ended substantive Qing authority over Outer Manchuria, with conflicts reduced to diplomatic coercion amid the dynasty's broader systemic decline.[16]Russian Acquisition Through Treaties

The Treaty of Nerchinsk, signed on August 27, 1689, between the Russian Empire and the Qing dynasty, initially delimited the Sino-Russian border along the Argun River and the Stanovoy Mountains, assigning the upper Amur River basin to Qing control and requiring Russian withdrawal from fortified outposts like Albazin to avert further military confrontation.[30] This agreement temporarily halted Russian eastward expansion into the Amur region amid Qing military superiority, establishing a precedent for diplomatic border resolution rather than conquest.[28] By the mid-19th century, Qing internal rebellions, including the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), and external pressures from the Opium Wars weakened Chinese administrative control over the sparsely populated Amur frontier, enabling Russian explorers and military expeditions under figures like Gennady Nevelskoy and Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky to assert de facto presence through settlement and navigation claims from 1849 onward.[31] Muravyov-Amursky's forces advanced along the Amur River, prompting negotiations under duress; on May 16, 1858, the Treaty of Aigun was concluded between Muravyov and Qing commissioner Yishan, ceding to Russia approximately 600,000 square kilometers north of the Amur River from the Argun confluence to the Pacific, including both banks in the estuary and adjacent islands, while designating the Amur as a shared navigational boundary.[4] This treaty effectively reversed key provisions of Nerchinsk by transferring the left (northern) bank territories without compensation, exploiting Qing diplomatic isolation during the Second Opium War.[10][12] The Convention of Peking, ratified on November 14, 1860, amid Qing defeats by Anglo-French forces and Russian opportunistic diplomacy via envoy Nikolay Ignatyev, confirmed the Aigun cessions and annexed an additional 400,000 square kilometers south of the Amur and east of the Ussuri River to Russia, establishing the modern Primorye territory and access to the Sea of Japan via the Golden Horn Bay.[2] These provisions, part of a broader settlement following the sack of Beijing's Summer Palace, granted Russia ice-free Pacific ports and resource-rich lands previously under nominal Qing suzerainty, totaling over 1 million square kilometers in Outer Manchuria acquired through these instruments.[6] Russian negotiators framed the acquisitions as corrections to ambiguous Nerchinsk boundaries based on prior explorations, though Qing records indicate coerced assent amid existential threats.[12] Subsequent border protocols, such as the 1881 Treaty of Saint Petersburg, minorly adjusted fringes but preserved the core 1858–1860 demarcations.[32]Tsarist Russian Settlement and Administration

The acquisition of Outer Manchuria through the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and the 1860 Treaty of Peking prompted immediate Russian efforts to populate and secure the Amur and Ussuri basins against Qing reconquest. Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky, serving as Governor-General of Eastern Siberia from 1847 to 1861, directed exploratory expeditions and founded strategic outposts, including Blagoveshchensk in 1856 at the Amur-Zeya confluence and Khabarovsk in 1858 at the Amur-Ussuri junction, to anchor Russian claims and facilitate navigation.[33] These sites initially housed military garrisons and Cossack squadrons, with detachments like the Amur Cossack Host established by 1860 to patrol frontiers and cultivate land for self-sufficiency.[34] Settlement accelerated after the 1861 emancipation of serfs, as the Imperial government incentivized voluntary migration from overcrowded western provinces through decrees offering up to 15 desyatins (16.4 hectares) of tax-exempt farmland per household, subsidized transport via steamers on the Amur, and loans for tools and livestock.[35] Political exiles and convicts supplemented free settlers, comprising up to 20% of early arrivals by the 1870s, providing labor for road-building, mining, and agriculture while introducing administrative expertise.[35] By the 1880s, over 10,000 households had been granted plots in the Amur valley alone, shifting the economy toward grain cultivation and fur trapping, though indigenous groups like Evenks and Nanais retained nominal autonomy under Russian oversight.[20] Administrative reforms culminated in the 1884 creation of the Priamurye Governor-Generalship, headquartered in Khabarovsk, which consolidated control over the Amur, Maritime, and Sakhalin districts previously fragmented under Irkutsk jurisdiction.[36] This entity, led by figures like Aleksey Peshkov, emphasized cadastral surveys to formalize land titles, suppression of illicit Chinese gold mining, and infrastructure like telegraph lines to Irkutsk by 1890, aiming to integrate the periphery into the imperial fiscal system.[36] Local governance relied on district ispravniks and volost assemblies dominated by Russian colonists, with Orthodox missions promoting cultural assimilation amid sparse policing of an estimated 500,000 square kilometers. Demographic expansion reflected these policies: the 1897 Imperial census recorded 120,306 residents in Amur Oblast and 223,336 in Primorskaya Oblast, up from fewer than 10,000 non-indigenous in 1861, with migrants—primarily Orthodox Russians and Ukrainians—outnumbering natives by over 5:1.[37] Urban centers like Vladivostok grew to 28,896 inhabitants, serving as naval bases, while rural densities remained low at under 1 person per square kilometer, underscoring the frontier's underdevelopment despite state subsidies exceeding 1 million rubles annually by 1900.[38]Soviet Era Transformations

![Flag of Khabarovsk Krai.svg.png][float-right] The Russian Far East, encompassing the territories of modern Primorsky Krai, Khabarovsk Krai, and Amur Oblast, underwent significant administrative reorganization following the Bolshevik consolidation of power. Initially established as the Far Eastern Republic in April 1920 to serve as a buffer against Japanese intervention during the Russian Civil War, the entity was integrated into the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic on November 15, 1922. From 1922 to 1926, it operated as the Far Eastern Oblast; subsequently, as the Far Eastern Krai until 1938, when it was divided into Khabarovsk Krai and Primorsky Krai to enhance regional governance and economic planning. These changes facilitated centralized Soviet control over the sparsely populated frontier.[39][40] Economic transformations emphasized rapid industrialization and collectivization, aligning with Stalin's Five-Year Plans. Agriculture, dominated by small-scale farming among Russian settlers and indigenous groups, was restructured through forced collectivization starting in 1929, forming kolkhozy and sovkhozy despite the region's challenging climate and limited fertile land, which constrained yields compared to western USSR districts. Industrial development prioritized extractive industries, including gold and tin mining, timber harvesting, and fish processing, supported by expanded rail networks and ports like Vladivostok. The Gulag system supplied forced labor for these projects, with camps in the Amur and Primorye areas contributing to infrastructure such as logging operations and penal railways, though exact prisoner numbers for the region remain estimates due to archival opacity.[41][42] Demographic shifts were profound, driven by purges and mass deportations to secure borders amid fears of espionage. In 1937, Soviet authorities deported approximately 171,781 ethnic Koreans from the Far East to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, labeling them as potential Japanese agents; this operation halved the Korean population in the region. Chinese residents faced similar fates, with NKVD orders leading to the arrest and expulsion of tens of thousands from enclaves like Vladivostok's "Millionka" between 1930 and 1937, reducing the Chinese presence from over 100,000 to negligible levels by the late 1930s. These policies promoted Slavic influx through incentives, increasing the Russian share of the population from around 60% in the 1920s to over 80% by 1959, while suppressing indigenous Evenks, Nanais, and others through cultural assimilation and relocation.[43][44] Militarily, the era saw escalating tensions with Japan, resolved through decisive Soviet victories. Border skirmishes peaked in the Battles of Khalkhin Gol (May–September 1939), where Soviet-Mongolian forces under Georgy Zhukov defeated Japanese troops, inflicting over 50,000 casualties and prompting a neutrality pact in April 1941. In August 1945, the USSR declared war on Japan, launching Operation August Storm into Manchuria with 1.5 million troops, capturing key cities and dismantling Japanese industrial assets for Soviet relocation, which accelerated post-war reconstruction in the Far East but strained local resources. These events solidified Soviet dominance, transforming the region into a fortified outpost against Asian threats.[45][46]Modern Russian Integration

Administrative Divisions

Outer Manchuria is administratively integrated into the Russian Federation as components of the Far Eastern Federal District, primarily comprising Primorsky Krai, the southern part of Khabarovsk Krai, Amur Oblast, and the Jewish Autonomous Oblast.[2][47] These federal subjects were established through Soviet-era consolidations and post-1991 reforms, overlaying the historical territories acquired via the Treaty of Aigun (1858) and Treaty of Peking (1860), with boundaries adjusted to align with rivers like the Amur and Ussuri.[48] Primorsky Krai governs the southeastern expanse, including the Ussuri River basin and Pacific coastline, with Vladivostok as its administrative center since its designation as a key port in the late 19th century.[49] Khabarovsk Krai covers northern riverine areas, incorporating segments along the Amur upstream of Khabarovsk, which serves as the krai's capital and a historical outpost established in 1632 by Russian explorers.[49] Amur Oblast administers the central Amur valley left bank, centered on Blagoveshchensk, reflecting its origins as a military district post-1858 annexation.[11] The Jewish Autonomous Oblast, created in 1934 as a Soviet experiment in Jewish settlement, manages a discrete enclave in the middle Amur basin adjacent to China, with Birobidzhan as its capital, though its ethnic Jewish population has since declined sharply.[2] These divisions operate under Russia's federal system, where krais and oblasts possess varying degrees of autonomy but are subordinate to Moscow for defense, foreign policy, and macroeconomic coordination. Local governance involves elected legislatures and governors appointed or elected per federal law, with economic development tied to federal programs emphasizing resource extraction and cross-border trade with China.[6] No distinct administrative status exists for "Outer Manchuria" itself, as Russian policy treats the area as irrevocably integrated territory without irredentist challenges from within the federation.[2]Demographic Composition and Migration Trends

The demographic composition of Outer Manchuria's constituent regions—primarily Amur Oblast, Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Khabarovsk Krai, and Primorsky Krai—is overwhelmingly dominated by ethnic Russians, who form over 90% of the population in most areas based on recent censuses. In Amur Oblast, Russians accounted for 95.17% of residents per the 2020 national census data.[50] Indigenous Tungusic groups such as Evenks, Nanai, and Udege constitute minor fractions, typically under 2% regionally, with their numbers further diminished by assimilation and out-migration.[51] Other minorities include Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Central Asians, but no single non-Russian group exceeds 3-5% in aggregate across the territories. Population totals have contracted steadily, reflecting low birth rates and net out-migration. The Jewish Autonomous Oblast recorded 150,453 residents in the 2021 census, declining to an estimated 145,802 by 2024.[52] Primorsky Krai's population fell to 1,845,165 in 2021 from prior peaks, with further estimates at 1,798,047 in 2024.[53] The broader Russian Far East has lost 20% of its inhabitants since 1991, with decline rates accelerating due to economic disparities favoring European Russia.[54] Migration trends since the Soviet collapse have been characterized by heavy outflows of ethnic Russians and other Slavic groups to western Russia, driven by better opportunities and infrastructure. Net migration turned negative in 1991, with annual losses compounding depopulation despite sporadic government incentives for resettlement.[55] Inflows from China involve temporary labor in agriculture, logging, and trade—estimated in tens of thousands annually—but permanent settlement remains limited, with many workers returning home amid regulatory crackdowns and economic reversals.[56] Claims of mass Chinese colonization lack substantiation in official data, as undocumented numbers do not translate to demographic shifts; official Chinese residents numbered under 40,000 nationwide in early 2000s censuses, with regional concentrations small relative to totals.[57] Indigenous mobility has declined, with communities increasingly urbanized and integrated into Russian-majority locales.[58]Economic Activities and Resource Management

The economy of Outer Manchuria relies heavily on natural resource extraction, agriculture, fisheries, and transportation infrastructure, reflecting the region's vast forests, mineral deposits, and arable lands in the Russian Far East. Mining constitutes a core activity, particularly gold extraction in Amur Oblast, which holds Russia's largest gold reserves and ranked sixth nationally in output as of 2007, contributing nearly 20% to the oblast's industrial production. Coal mining predominates in Zabaykalsky Krai, accounting for 5.3% of Far Eastern coal output, with operations like those of SUEK supplying domestic energy needs. Forestry and timber processing are vital in Khabarovsk Krai, where reserves support industry comprising 17.9% of gross regional product, alongside tin production and energy generation exceeding one-fifth of the Far Eastern Federal District's total electricity and thermal output.[59][60][61] Agriculture focuses on grain, soybeans, and vegetables, with Amur Oblast producing two-thirds of the Far East's grain and half its soybeans, bolstered by favorable soils and federal incentives for crop specialization. The Jewish Autonomous Oblast emphasizes soybeans, potatoes, and fodder grains, which form over 3% of regional GDP and support livestock through expanded cultivation since the 2010s. Fisheries thrive in Primorsky Krai, leveraging Pacific access for processing and exports, while transportation—particularly ports and rail—facilitates trade, with logistics driving income growth amid Russia-China exchanges. These sectors underpin federal development priorities, including the 2019-2024 Far Eastern programs targeting resource-based growth.[62][63][61] Resource management emphasizes state licensing and quotas under Russia's Forest Code, yet faces challenges from illegal logging, biodiversity loss, and inadequate regeneration, as highlighted by environmental NGOs critiquing wood-centric practices over ecosystem services like watershed protection. In forestry, federal policies promote auctions and reforestation, but ground-level enforcement lags, exacerbating disturbances in Khabarovsk and Primorsky areas. Mining operations in Amur and Zabaykalsky prioritize open-pit methods for efficiency, with reserves exceeding 1 billion tonnes of coal in Khabarovsk, though air pollution and waste management strain local ecosystems. Agricultural expansion, including soybean cooperatives with China, has boosted yields—reaching near-national averages by 2022 in Amur—but raises concerns over soil degradation without integrated sustainability measures. Overall, management balances export revenues with federal subsidies, prioritizing economic output amid geopolitical trade shifts.[64][65][61][66]Claims, Disputes, and Perspectives

Chinese Nationalist and Irredentist Views

Chinese nationalists and irredentists consider the territories comprising Outer Manchuria—roughly 1 million square kilometers ceded by the Qing dynasty to the Russian Empire—as integral historical Chinese lands unjustly lost through coercive 19th-century treaties. These include the Treaty of Aigun on May 16, 1858, which transferred the left bank of the Amur River, and the Convention of Peking on November 14, 1860, which ceded the area east of the Ussuri River, including Primorsky Krai.[67][68] They frame these agreements as exemplars of the "unequal treaties" imposed during China's "century of humiliation," arguing that the Qing's military weakness and internal instability enabled Russian expansionism rather than legitimate negotiation.[17] Irredentist rhetoric emphasizes demographic and cultural precedents, citing pre-19th-century Chinese settlement, Manchu administrative control, and ancient maps depicting the region—such as 13th-century cartography showing areas around modern Vladivostok (rechristened Hǎishēnwǎi in Chinese usage) as Chinese territory.[67] Some nationalists advocate demographic reclamation through migration and economic dominance in the sparsely populated Russian Far East, where Chinese workers and investments have surged, potentially creating de facto influence without immediate conflict.[69] Public expressions include online forums and opinion pieces urging Beijing to exploit Russian vulnerabilities, such as post-Ukraine war weaknesses, to press claims, though these remain marginal compared to official border affirmations in the 2004 Sino-Russian agreement.[70][17] Recent actions fueling irredentist sentiments involve state-affiliated maps, like the 2023 Ministry of Natural Resources publication using pre-Russian Chinese toponyms for Russian Far East locales, including Vladivostok and Bolshoi Ussuriysky Island, prompting Russian security concerns over historical revisionism.[71][72] Analysts note that while the Chinese Communist Party prioritizes strategic partnership with Moscow, nationalist narratives align with Xi Jinping's "great rejuvenation" discourse, portraying territorial recovery as unfinished business, potentially escalating if Sino-Russian ties fray.[2][73] These views, often disseminated via social media and semi-official channels, contrast with Beijing's diplomatic restraint but underscore persistent grievances over historical losses exceeding those to other powers. However, military recovery of these regions by China remains infeasible, given Russia's second-ranked global military position, its nuclear arsenal exceeding China's in size, and experienced land forces suited to the Siberian terrain; the Sino-Russian strategic partnership, which includes affirmations of no territorial claims, further precludes such pursuits, with the risk of nuclear escalation rendering them prohibitive.[74][75][76]Russian Official and Nationalist Positions

The Russian government maintains that the territories comprising Outer Manchuria, acquired through the Treaty of Aigun in 1858 and the Convention of Peking in 1860, constitute integral parts of the Russian Federation, with sovereignty unchallenged by subsequent border demarcations.[77] In the 2004 Supplementary Agreement on the Eastern Section of the China-Russia Border, both nations affirmed the definitive delimitation of their shared boundary, with Article 6 explicitly stating that neither party harbors territorial claims against the other, thereby resolving all disputes including those pertaining to islands like Bolshoi Ussuriysky.[2] This position aligns with earlier protocols from 1991 and 2001, which Russia interprets as conclusive validation of the 19th-century treaties' outcomes, rejecting characterizations of them as "unequal" as ahistorical revisionism disconnected from the geopolitical realities of Qing military weakness and Russian exploratory advances along the Amur River.[78] Official Russian responses to sporadic Chinese cartographic assertions or nationalist rhetoric depicting the Russian Far East as historically Chinese have been dismissive or silent, underscoring confidence in the legal finality of bilateral accords and the demographic entrenchment of Russian-majority populations in regions like Primorsky Krai and Khabarovsk Krai.[71] President Vladimir Putin has acknowledged the Qing origins of the area while promoting policies to bolster Russian settlement and economic integration, such as the 2016 Far Eastern Hectare program, which allocates land to citizens to counter migration imbalances without conceding territorial legitimacy.[79] The Kremlin frames any Chinese irredentist undercurrents as marginal and incompatible with the strategic partnership forged since the 2000s, prioritizing joint development over historical grievances.[6] Russian nationalists, drawing on imperial historiography, portray the 19th-century annexations as rightful civilizational expansion into undergoverned frontier zones, crediting Tsarist initiatives with transforming sparsely populated Manchu tributaries into viable economic hubs through Russian infrastructure, agriculture, and defense against Japanese and Qing threats.[80] Figures in Primorsky Krai and broader nationalist circles vehemently oppose Chinese claims, viewing them as expansionist pretexts masked by demographic infiltration via labor migration, which they quantify as exceeding sustainable levels—e.g., Chinese workers comprising up to 20% of certain sectors by the early 2000s—potentially eroding Russian ethnic predominance without formal territorial demands.[81] Organizations and commentators emphasize the region's Russification since the 1860s, citing census data showing ethnic Russians at over 90% in key areas like Vladivostok by 2021, and decry "kitaizatsiya" (Sinicization) narratives as alarmist only insofar as they underestimate Beijing's long-term demographic leverage.[82] Nationalist discourse often invokes defensive irredentism, arguing that reversion to China would betray the sacrifices of Russian settlers and soldiers who secured the Pacific coast amid 19th-century power vacuums, while dismissing Qing suzerainty as nominal overlordship lacking effective control or infrastructure investment.[83] Events like the 2020 Vladivostok foundation anniversary celebrations have galvanized patriotic assertions of the city's indelible Russian identity, countering Chinese online backlash as unsubstantiated revanchism unfit for modern interstate relations.[84] Overall, these positions prioritize empirical markers of Russian stewardship—resource extraction yielding billions in annual GDP from Amur and Primorye oblasts—over abstract historical entitlements, framing the territory's retention as essential to national security amid China's rising influence.[85]International and Scholarly Assessments

The Sino-Russian border, encompassing the territories historically termed Outer Manchuria, has been internationally recognized as settled through a series of agreements, culminating in the 1991 Sino-Soviet border agreement and supplementary protocols ratified in 2004 and 2008, which delineated the final boundary along the Amur and Ussuri rivers without territorial concessions from either side.[86] These accords resolved lingering disputes from 19th-century treaties, affirming Russian sovereignty over Primorsky Krai, Khabarovsk Krai, and Amur Oblast, with no formal challenges raised in international forums such as the United Nations.[86] Under principles of international law, including pacta sunt servanda, the enduring validity of these treaties—despite their origins in asymmetrical power dynamics—has precluded revisionist claims, as evidenced by China's consistent adherence in bilateral diplomacy and multilateral recognition of post-1991 demarcations.[87] Scholarly assessments generally characterize the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and 1860 Convention of Peking as products of Qing China's military vulnerabilities during the Opium Wars era, resulting in the cession of approximately 1 million square kilometers to Russia, but emphasize that subsequent demographic integration, infrastructure development, and mutual border stabilizations have entrenched Russian control.[10] Historians note these pacts as exemplars of 19th-century imperial expansion, akin to other contemporaneous land transfers, yet highlight China's pragmatic foreign policy under Deng Xiaoping and successors, which prioritized economic cooperation over revanchism, as seen in the 2001 Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation.[88] Academic analyses, drawing on declassified diplomatic records, underscore that while nationalist narratives in Chinese media occasionally invoke "lost territories" for domestic mobilization, official Beijing has avoided irredentist rhetoric to maintain strategic alignment against Western pressures, with irredentism confined to fringe online discourse rather than state doctrine.[89] International relations experts assess the stability of the status quo as bolstered by Russia's resource exports to China and shared geopolitical interests, rendering territorial revision improbable absent a collapse in bilateral ties; simulations of conflict scenarios, such as those modeling Russian Far East vulnerabilities, predict Chinese opportunism only under extreme conditions like state fragmentation, not current realist calculations.[90] Critiques from Western scholars often frame the acquisitions within broader critiques of tsarist expansionism, yet acknowledge that prescriptive international law favors uti possidetis principles—preserving post-colonial borders—over historical grievance rectification, as applied in cases like Latin American independences.[91] Empirical studies of border disputes indicate that Sino-Russian demarcation ranks among the most successfully resolved globally since 1945, with minimal militarized incidents post-1969 clashes, attributing endurance to economic interdependence exceeding $200 billion annually in trade by 2023.[86]Toponymy and Cultural References

Dual Naming Conventions

In Chinese official cartography and documentation, locations within Outer Manchuria are frequently denoted using historical Chinese toponyms alongside or in substitution for their modern Russian designations, a practice that underscores continuity with Qing-era administration prior to the territorial cessions formalized by the Treaty of Aigun on May 16, 1858, and the Treaty of Peking on November 14, 1860.[92][67] This asymmetric dual naming persists primarily in Chinese contexts, where it serves to evoke pre-Russification geography, rather than in Russian administration, which has systematically Russified indigenous, Manchu, and Chinese-derived names since the mid-19th century.[93] For instance, in 2023, China's Ministry of Natural Resources mandated the inclusion of such legacy names on national maps for eight key sites, including major cities and geographical features, to standardize exonyms and preserve historical nomenclature.[93][94] These Chinese names often originated as transliterations of local Nanai, Udege, or Manchu terms during Qing oversight of the region, adapted into hanzi characters for administrative use.[92] Russian renaming efforts intensified under Tsarist expansion and continued through Soviet indigenization policies in the 1920s–1930s, replacing many with Slavic or descriptive terms, though some indigenous variants were occasionally retained or revived post-1970s for cultural recognition.[92] In contemporary Russia, official toponymy remains monolingual in Russian, with no formal endorsement of Chinese equivalents, reflecting the region's integration as federal subjects like Primorsky Krai and Khabarovsk Krai since the 19th century.[93] Chinese usage, by contrast, appears in state media, education, and irredentist discourse, where names like Hǎishēnwǎi for Vladivostok are invoked to highlight perceived historical injustices of the "unequal treaties."[67][94] The following table enumerates prominent examples of this dual nomenclature, drawing from Qing records and modern Chinese mappings:| Russian Name | Chinese Historical Name | Pinyin Transcription | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vladivostok | 海参崴 | Hǎishēnwǎi | Refers to sea cucumber habitat; site of Russian fort established 1860.[92][67] |

| Khabarovsk | 伯力 | Bólì | Derived from Nanai term for "pine tree"; founded as military outpost 1858.[93] |

| Blagoveshchensk | 海兰泡 | Hǎilánpào | Indicates "sea orchid bubble" (lagoon); border city opposite Heihe.[93] |

| Nikolayevsk-on-Amur | 庙街 | Miàojiē | "Temple street"; key Amur River port developed 1850s.[93] |

| Sakhalin Island | 库页岛 | Kùyèdǎo | From Ainu "island at the edge"; claimed by Qing until 1860, fully Russian by 1875.[93][92] |

| Stanovoy Range | 外兴安岭 | Wài Xīng'ān Lǐng | "Outer Xing'an Mountains"; natural boundary per 1858 treaty.[93] |