Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Proopiomelanocortin

View on Wikipedia

| Opioids neuropeptide | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Op_neuropeptide | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08035 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013532 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00964 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) is a precursor polypeptide with 241 amino acid residues. POMC is synthesized in corticotrophs of the anterior pituitary from the 267-amino-acid-long polypeptide precursor pre-pro-opiomelanocortin (pre-POMC), by the removal of a 26-amino-acid-long signal peptide sequence during translation.[5] POMC is part of the central melanocortin system.

Gene

[edit]The POMC gene is located on chromosome 2p23.3. This gene encodes a 285-amino acid polypeptide hormone precursor that undergoes extensive, tissue-specific, post-translational processing via cleavage by subtilisin-like enzymes known as prohormone convertases.

Tissue distribution

[edit]The POMC gene is expressed in both the anterior and intermediate lobes of the pituitary gland. Its protein product is primarily synthesized by corticotropic cells in the anterior pituitary, but it is also produced in several other tissues:

- Corticotropic cells of the anterior pituitary gland

- Melanotropic cells of the intermediate lobe of the pituitary gland

- Neurons of the arcuate nucleus (infundibular nucleus) in the hypothalamus[6][7]

- Smaller populations of neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus and brainstem

- Melanocytes in the skin.[8]

Function

[edit]POMC is cut (cleaved) to give rise to multiple peptide hormones. Each of these peptides is packaged in large dense-core vesicles that are released from the cells by exocytosis in response to appropriate stimulation:[citation needed]

- α-MSH produced by neurons in the ventromedial nucleus has important roles in the regulation of appetite (POMC neuron stimulation results in satiety.[9]) and sexual behavior, while α-MSH secreted from the intermediate lobe of the pituitary regulates the movement of melanin produced from melanocytes in skin.

- ACTH is a peptide hormone that regulates the secretion of mainly glucocorticoids from the cells of the zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex. ACTH can also regulate secretion of gonadocorticoids from the cells of the zona reticularis since they also express ACTH receptors.

- β-Endorphin and [Met]enkephalin are endogenous opioid peptides with widespread actions in the brain.

Post-translational modifications

[edit]The POMC gene encodes a 285-amino acid polypeptide precursor that undergoes extensive, tissue-specific post-translational processing. This processing is primarily mediated by subtilisin-like prohormone convertases, which cleave the precursor at specific basic amino acid sequences—typically Arg-Lys, Lys-Arg, or Lys-Lys.

In many tissues, four primary cleavage sites are utilized, resulting in the production of two major bioactive peptides: adrenocorticotrophin (ACTH), which is essential for normal steroidogenesis and adrenal gland maintenance, and β-lipotropin. However, the POMC precursor contains at least eight potential cleavage sites, and depending on the tissue type and the specific convertases expressed, it can be processed into up to ten biologically active peptides with diverse functions.

Key processing enzymes include prohormone convertase 1 (PC1), prohormone convertase 2 (PC2), carboxypeptidase E (CPE), peptidyl α-amidating monooxygenase (PAM), N-acetyltransferase (N-AT), and prolylcarboxypeptidase (PRCP).[citation needed]

In addition to proteolytic cleavage, POMC processing involves other post-translational modifications such as glycosylation and acetylation. The specific pattern of cleavage and modification is tissue-dependent. For example, in the hypothalamus, placenta, and epithelium, all cleavage sites may be active, generating peptides involved in pain modulation, energy homeostasis, immune responses, and melanocyte stimulation. These peptides include multiple melanotropins, lipotropins, and endorphins, many of which are derived from the larger ACTH and β-lipotropin peptides.[citation needed]

Derivatives

[edit]The large POMC precursor is the source of numerous biologically active peptides, which are produced through sequential enzymatic cleavage. These include:

N-Terminal Peptide of Proopiomelanocortin (NPP, or pro-γ-MSH) α-Melanotropin (α-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone, or α-MSH) β-Melanotropin (β-MSH) γ-Melanotropin (γ-MSH) 𝛿-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone (𝛿-MSH), found in sharks[10] ε-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone (ε-MSH), present in some teleost fish[11] Corticotropin (Adrenocorticotropic Hormone, or ACTH) Corticotropin-like Intermediate Peptide (CLIP) β-Lipotropin (β-LPH) Gamma Lipotropin (γ-LPH) β-Endorphin [Met]Enkephalin Although the first five amino acids of β-Endorphin are identical to [Met]enkephalin,[12] β-Endorphin is not generally believed to be a precursor of [Met]enkephalin.[citation needed] Instead, [Met]enkephalin is produced independently from its own precursor, proenkephalin A.

The production of β-MSH occurs in humans, but not in mice or rats, due to the absence of the necessary cleavage site in the rodent POMC sequence.

Regulation by the photoperiod

[edit]The levels of proopiomelanocortin (pomc) are regulated indirectly in some animals by the photoperiod. It is referred to[clarification needed] the hours of light during a day and it changes across the seasons. Its regulation depends on the pathway of thyroid hormones that is regulated directly by the photoperiod. An example are the siberian hamsters who experience physiological seasonal changes dependent on the photoperiod. During spring in this species, when there is more than 13 hours of light per day, iodothyronine deiodinase 2 (DIO2) promotes the conversion of the prohormone thyroxine (T4) to the active hormone triiodothyronine (T3) through the removal of an iodine atom on the outer ring. It allows T3 to bind to the thyroid hormone receptor (TR), which then binds to thyroid hormone response elements (TREs) in the DNA sequence. The pomc proximal promoter sequence contains two thyroid-receptor 1b (Thrb) half-sites: TCC-TGG-TGA and TCA-CCT-GGA indicating that T3 may be capable of directly regulating pomc transcription. For this reason during spring and early summer, the level of pomc increases due to the increased level of T3.[13]

However, during autumn and winter, when there is less than 13 hours of light per day, iodothyronine desiodinase 3 removes an iodine atom which converts thyroxine to the inactive reverse triiodothyronine (rT3), or which converts the active triiodothyronine to diiodothyronine (T2). Consequently, there is less T3 and it blocks the transcription of pomc, which reduces its levels during these seasons.[14]

Influences of photoperiods on relevant similar biological endocrine changes that demonstrate modifications of thyroid hormone regulation in humans have yet to be adequately documented.

Clinical significance

[edit]Mutations in the POMC gene have been associated with early-onset obesity,[15] adrenal insufficiency, and red hair pigmentation.[16]

In cases of primary adrenal insufficiency, decreased cortisol production leads to compensatory overproduction of pituitary ACTH through feedback mechanisms. Because ACTH is co-produced with α-MSH and γ-MSH from POMC, this overproduction can result in hyperpigmentation.[17]

A specific genetic polymorphism in the POMC gene is associated with elevated fasting insulin levels, but only in obese individuals. The melanocortin signaling pathway may influence glucose metabolism in the context of obesity, indicating a possible gene–environment interaction. Thus, POMC variants may contribute to the development of polygenic obesity and help explain the connection between obesity and type 2 diabetes.[18]

Increased circulating levels of POMC have also been observed in patients with sepsis.[19] While the clinical implications of this finding are still under investigation, animal studies have shown that infusion of hydrocortisone in septic mice suppresses ACTH (a downstream product of POMC) without reducing POMC levels themselves.[20]

Drug target

[edit]POMC is a pharmacological target for obesity treatment. The combination drug naltrexone/bupropion acts on hypothalamic POMC neurons to reduce appetite and food intake.[21]

In rare cases of POMC deficiency, treatment with setmelanotide, a selective melanocortin-4 receptor agonist, has been effective. Two individuals with confirmed POMC deficiency showed clinical improvement following this therapy.[22]

Dogs

[edit]A deletion mutation common in Labrador Retriever and Flat-coated Retriever dogs is associated with increased interest in food and subsequent obesity.[23]

Interactions

[edit]Proopiomelanocortin has been shown to interact with melanocortin 4 receptor.[24][25] The endogenous agonists of melanocortin 4 receptor include α-MSH, β-MSH, γ-MSH, and ACTH. The fact that these are all cleavage products of POMC should suggest likely mechanisms of this interaction.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000115138 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000020660 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "pro-opiomelanocortin preproprotein [Homo sapiens] - Protein - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Sukhov RR, Walker LC, Rance NE, Price DL, Young WS 3rd (1995). "Opioid precursor gene expression in the human hypothalamus". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 353 (4): 604–622. doi:10.1002/cne.903530410. PMC 9853479. PMID 7759618.

- ^ Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, Cerdán MG, Diano S, Horvath TL, et al. (May 2001). "Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus" (PDF). Nature. 411 (6836): 480–484. Bibcode:2001Natur.411..480C. doi:10.1038/35078085. hdl:11336/71802. PMID 11373681. S2CID 4342893.

- ^ Rousseau K, Kauser S, Pritchard LE, Warhurst A, Oliver RL, Slominski A, et al. (2007). "Proopiomelanocortin (POMC), the ACTH/melanocortin precursor, is secreted by human epidermal keratinocytes and melanocytes and stimulates melanogenesis". FASEB Journal. 21 (8): 1844–1856. doi:10.1096/fj.06-7398com. PMC 2253185. PMID 17317724.

- ^ Varela L, Horvath TL (December 2012). "Leptin and insulin pathways in POMC and AgRP neurons that modulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis". EMBO Reports. 13 (12): 1079–1086. doi:10.1038/embor.2012.174. PMC 3512417. PMID 23146889.

- ^ Dores RM, Cameron E, Lecaude S, Danielson PB (August 2003). "Presence of the delta-MSH sequence in a proopiomelanocortin cDNA cloned from the pituitary of the galeoid shark, Heterodontus portusjacksoni". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 133 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1016/S0016-6480(03)00151-5. PMID 12899848.

- ^ Harris RM, Dijkstra PD, Hofmann HA (January 2014). "Complex structural and regulatory evolution of the pro-opiomelanocortin gene family". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 195: 107–115. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.10.007. PMID 24188887.

- ^ Cullen JM, Cascella M (2022). "Physiology, Enkephalin". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32491696. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ Barrett P, Ebling FJ, Schuhler S, Wilson D, Ross AW, Warner A, et al. (August 2007). "Hypothalamic thyroid hormone catabolism acts as a gatekeeper for the seasonal control of body weight and reproduction". Endocrinology. 148 (8): 3608–3617. doi:10.1210/en.2007-0316. PMID 17478556. S2CID 28088190.

- ^ Bao R, Onishi KG, Tolla E, Ebling FJ, Lewis JE, Anderson RL, et al. (June 2019). "Genome sequencing and transcriptome analyses of the Siberian hamster hypothalamus identify mechanisms for seasonal energy balance". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (26): 13116–13121. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11613116B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1902896116. PMC 6600942. PMID 31189592.

- ^ Kuehnen P, Mischke M, Wiegand S, Sers C, Horsthemke B, Lau S, et al. (2012). "An Alu element-associated hypermethylation variant of the POMC gene is associated with childhood obesity". PLOS Genetics. 8 (3) e1002543. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002543. PMC 3305357. PMID 22438814.

- ^ "POMC proopiomelanocortin". Entrez Gene.

- ^ Boron WG, Boulpaep EL, eds. (2017). Medical Physiology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4557-4377-3.

- ^ Mohamed FE, Hamza RT, Amr NH, Youssef AM, Kamal TM, Mahmoud RA (2017). "Study of obesity associated proopiomelanocortin gene polymorphism: Relation to metabolic profile and eating habits in a sample of obese Egyptian children and adolescents". Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. 18 (1): 67–73. doi:10.1016/j.ejmhg.2016.02.009.

- ^ Téblick A, Vander Perre S, Pauwels L, Derde S, Van Oudenhove T, Langouche L, et al. (February 2021). "The role of pro-opiomelanocortin in the ACTH-cortisol dissociation of sepsis". Critical Care. 25 (1) 65. doi:10.1186/s13054-021-03475-y. PMC 7885358. PMID 33593393.

- ^ Téblick A, De Bruyn L, Van Oudenhove T, Vander Perre S, Pauwels L, Derde S, et al. (January 2022). "Impact of Hydrocortisone and of CRH Infusion on the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Axis of Septic Male Mice". Endocrinology. 163 (1) bqab222. doi:10.1210/endocr/bqab222. PMC 8599906. PMID 34698826.

- ^ Billes SK, Sinnayah P, Cowley MA (June 2014). "Naltrexone/bupropion for obesity: an investigational combination pharmacotherapy for weight loss". Pharmacological Research. 84: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2014.04.004. PMID 24754973.

- ^ Kühnen P, Clément K, Wiegand S, Blankenstein O, Gottesdiener K, Martini LL, et al. (July 2016). "Proopiomelanocortin Deficiency Treated with a Melanocortin-4 Receptor Agonist". The New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (3): 240–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1512693. PMID 27468060.

- ^ Raffan E, Dennis RJ, O'Donovan CJ, Becker JM, Scott RA, Smith SP, et al. (May 2016). "A Deletion in the Canine POMC Gene Is Associated with Weight and Appetite in Obesity-Prone Labrador Retriever Dogs". Cell Metabolism. 23 (5): 893–900. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.012. PMC 4873617. PMID 27157046.

- ^ Yang YK, Fong TM, Dickinson CJ, Mao C, Li JY, Tota MR, et al. (December 2000). "Molecular determinants of ligand binding to the human melanocortin-4 receptor". Biochemistry. 39 (48): 14900–11. doi:10.1021/bi001684q. PMID 11101306.

- ^ Yang YK, Ollmann MM, Wilson BD, Dickinson C, Yamada T, Barsh GS, et al. (March 1997). "Effects of recombinant agouti-signaling protein on melanocortin action". Molecular Endocrinology. 11 (3): 274–80. doi:10.1210/mend.11.3.9898. PMID 9058374.

Further reading

[edit]- Millington GW (May 2006). "Proopiomelanocortin (POMC): the cutaneous roles of its melanocortin products and receptors". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 31 (3): 407–12. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02128.x. PMID 16681590. S2CID 25213876.

- Millington GW (September 2007). "The role of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurones in feeding behaviour". Nutrition & Metabolism. 4: 18. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-4-18. PMC 2018708. PMID 17764572.

- Bhardwaj RS, Luger TA (1994). "Proopiomelanocortin production by epidermal cells: evidence for an immune neuroendocrine network in the epidermis". Archives of Dermatological Research. 287 (1): 85–90. doi:10.1007/BF00370724. PMID 7726641. S2CID 33604397.

- Raffin-Sanson ML, de Keyzer Y, Bertagna X (August 2003). "Proopiomelanocortin, a polypeptide precursor with multiple functions: from physiology to pathological conditions". European Journal of Endocrinology. 149 (2): 79–90. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1490079. PMID 12887283.

- Dores RM, Lecaude S (May 2005). "Trends in the evolution of the proopiomelanocortin gene". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 142 (1–2): 81–93. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.02.003. PMID 15862552.

- König S, Luger TA, Scholzen TE (October 2006). "Monitoring neuropeptide-specific proteases: processing of the proopiomelanocortin peptides adrenocorticotropin and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone in the skin". Experimental Dermatology. 15 (10): 751–61. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00472.x. PMID 16984256. S2CID 32034934.

- Farooqi S, O'Rahilly S (December 2006). "Genetics of obesity in humans". Endocrine Reviews. 27 (7): 710–18. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0040. PMID 17122358.

External links

[edit]- Pro-Opiomelanocortin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P01189 (Pro-opiomelanocortin) at the PDBe-KB.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Reference Sequence collection. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

This article incorporates public domain material from Reference Sequence collection. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Proopiomelanocortin

View on GrokipediaGenetics and Molecular Structure

Gene Location and Organization

The human POMC gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 2 at the cytogenetic band 2p23.3.[7] This positioning is highly conserved across mammalian species, with orthologous genes found on syntenic regions in rodents (e.g., mouse chromosome 12) and other vertebrates, reflecting evolutionary preservation of its regulatory architecture.[8] The gene spans approximately 7.8 kb and consists of three exons separated by two large introns.[2] Exon 1 is non-coding, comprising the 5' untranslated region (UTR) and harboring key promoter elements. Exon 2 encodes the signal peptide and the N-terminal portion of the prohormone, including the translation initiation site. Exon 3 contains the majority of the coding sequence for the core polyprotein precursor, along with the 3' UTR.[9] The promoter region upstream of exon 1 includes multiple regulatory elements that control POMC transcription. Notably, glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) mediate negative feedback by glucocorticoids, binding the glucocorticoid receptor to repress expression, while cAMP response elements (CREs) facilitate activation via cAMP-dependent pathways, such as those triggered by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH).[10] These elements are critical for tissue-specific and stimulus-responsive regulation in the pituitary and hypothalamus.[2] Certain structural variants in the POMC gene influence transcription. A prominent example is an Alu element-associated hypermethylation variant in the promoter region, which correlates with increased DNA methylation and reduced POMC expression, contributing to obesity risk in humans.[11] Other polymorphisms, such as rs2071345 in the upstream region, have been linked to altered transcriptional efficiency and associated phenotypes like alcohol dependence.[12]Protein Primary Structure

Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) is a precursor protein in humans consisting of 267 amino acids in its prepro form, including a 26-residue N-terminal signal peptide that directs the protein to the secretory pathway and is cleaved upon entry into the endoplasmic reticulum, yielding a mature POMC of 241 amino acids. The primary amino acid sequence of human POMC, encoded by the POMC gene on chromosome 2, features a linear polypeptide chain with distinct regions that serve as precursors for multiple bioactive peptides.[13] The protein's structure includes an N-terminal region encompassing pro-gamma-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (pro-γ-MSH, residues 27–102 post-signal cleavage), followed by a joining peptide (residues 103–137) that links it to the central core. The central region contains sequences for adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH, residues 138–176), α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH, residues 138–150 within ACTH), β-lipotropin (β-LPH, residues 177–267), and β-endorphin (residues 237–267 within β-LPH). These domains are organized such that the N-terminal and joining peptide regions are encoded primarily by exon 2 of the POMC gene, while the central and C-terminal sequences span exons 2 and 3.[13] Specific cleavage sites within the POMC sequence are marked by dibasic residue pairs, such as Lys-Arg and Lys-Lys, which are recognized by prohormone convertases PC1/3 and PC2 for subsequent processing into mature peptides; examples include the Arg49-Lys50 site in the N-terminal region and Lys-Lys pairs flanking ACTH and β-LPH. These sites ensure tissue-specific proteolytic maturation but are inherent to the primary structure of the intact precursor. Post-translational modifications on the POMC precursor itself include N-glycosylation at asparagine residue 47 (Asn47) in the pro-γ-MSH domain, which contributes to proper folding and stability in the secretory pathway, as well as O-glycosylation at threonine 45 (Thr45) that can modulate cleavage efficiency at nearby sites.Expression and Tissue Distribution

Sites of Expression

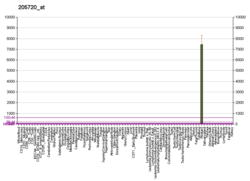

Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) is predominantly expressed in the anterior pituitary gland, specifically within corticotroph cells, where it serves as the primary precursor for adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). According to GTEx data, POMC mRNA expression is overexpressed approximately 52.5-fold in the pituitary compared to other tissues, making it the site of highest expression across the human body. This high level has been confirmed through quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analyses, which demonstrate significantly elevated POMC mRNA in pituitary tissue relative to other organs. In situ hybridization studies further localize this expression to endocrine cells in the anterior lobe, accounting for the majority of systemic POMC production under basal conditions.[14][15][16] Within the central nervous system, POMC expression is notable in neuroendocrine cells of the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, where it contributes to neuronal signaling related to energy balance. Detection via in situ hybridization and qPCR reveals moderate POMC mRNA levels in this region, though substantially lower than in the pituitary—representing a smaller fraction of total central POMC transcripts. Additional hypothalamic sites show trace expression, but the arcuate nucleus remains the principal locus. Cellular localization studies using immunohistochemistry confirm confinement to neuronal populations in these areas.[2][1] Peripheral expression of POMC occurs at lower levels in various endocrine and neuroendocrine cells across multiple tissues. In the skin, POMC mRNA is detectable in melanocytes and keratinocytes, as shown by qPCR and in situ hybridization, supporting local peptide production. The placenta exhibits POMC gene expression during gestation, primarily in trophoblast cells, identified through PCR-based methods. In the gastrointestinal tract, including the duodenum and colon, POMC mRNA has been observed via Northern blot and qPCR, localized to enteroendocrine cells. The adrenal medulla shows low-level POMC expression in chromaffin cells, quantifiable by qPCR but functionally minor compared to central sites. Overall, these peripheral sites contribute modestly to total POMC under basal conditions, with expression levels orders of magnitude below those in the pituitary.[2][17]Developmental and Environmental Regulation of Expression

The expression of the proopiomelanocortin (POMC) gene in the mouse pituitary begins during embryonic development, with onset observed around embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) in the developing Rathke's pouch, coinciding with the initiation of corticotroph differentiation following Tpit expression at E11.5.[18] This early expression marks the emergence of POMC-producing cells prior to full maturation of the anterior pituitary. POMC transcript levels then increase progressively, reaching a peak in the postnatal period as corticotrophs undergo maturation and enhance their secretory capacity.[19] Several transcription factors play critical roles in activating the POMC promoter during development and in mature cells. Tpit (TBX19), a T-box transcription factor restricted to corticotrophs and melanotrophs, is essential for corticotroph lineage commitment and directly activates POMC transcription by binding to specific response elements in the promoter. NeuroD1, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, binds directly to E-box motifs in the POMC promoter, forming heterodimers that drive robust activation of transcription in pituitary corticotrophs.[20] Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), while not a transcription factor itself, activates the POMC promoter indirectly by stimulating cAMP production and subsequent recruitment of downstream factors like Nur77 to responsive elements.[21] Environmental cues significantly modulate POMC gene transcription in response to physiological demands. Stress hormones such as CRH and arginine vasopressin (AVP) upregulate POMC expression in pituitary corticotrophs primarily through the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway, which enhances promoter activity and ACTH production to mount an adaptive stress response.[22] In contrast, glucocorticoids exert negative feedback by binding to glucocorticoid receptors, which repress POMC transcription via inhibition of cAMP-responsive elements and recruitment of corepressors to the promoter.[23] Epigenetic mechanisms further restrict POMC expression to specific tissues. The POMC promoter contains CpG islands that are heavily methylated in non-pituitary tissues, such as liver and placenta, leading to chromatin condensation and transcriptional silencing.[24] This methylation pattern contrasts with the hypomethylated state in pituitary corticotrophs, where it permits active transcription, highlighting tissue-specific epigenetic control.Biosynthesis and Post-Translational Processing

Cleavage Mechanisms

Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) undergoes endoproteolytic cleavage primarily by prohormone convertases PC1/3 and PC2, which recognize and cleave at paired dibasic amino acid residues (Lys-Arg or Arg-Arg) within the precursor protein.[25] These enzymes initiate processing in the trans-Golgi network and continue in immature secretory granules, where the acidic environment (pH 4.5–5.5) and increasing calcium concentrations optimize their activity. Post-cleavage, carboxypeptidase E (CPE) removes the exposed C-terminal basic residues, and peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase (PAM) catalyzes C-terminal amidation of specific peptides, enhancing their stability and bioactivity.[25] Processing is highly tissue-specific, reflecting differential expression of the convertases. In anterior pituitary corticotrophs, PC1/3 predominates and cleaves POMC to generate adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and β-lipotropin (β-LPH), with minimal further processing due to low PC2 levels.[25] In contrast, melanotrophs of the intermediate pituitary lobe express high levels of both PC1/3 and PC2; PC1/3 performs initial cleavages, while PC2 subsequently processes β-LPH to β-endorphin and γ-lipotropin (γ-LPH), and ACTH to α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) precursors. This sequential action in secretory granules ensures efficient maturation of peptides for regulated secretion.[25] Species differences influence cleavage efficiency and product profiles. Rodents produce higher levels of γ-LPH because their POMC sequence lacks a dibasic cleavage site within this region, preventing further processing into certain γ-MSH variants that occur in humans.[25] Additionally, rodents possess a prominent intermediate pituitary lobe, enabling robust PC2-mediated processing to α-MSH and β-endorphin, whereas humans have a vestigial intermediate lobe, resulting in less extensive melanotroph-like processing.[25]Derived Peptides and Hormones

Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) is cleaved to generate several bioactive peptides and hormones, primarily through tissue-specific proteolytic processing. The major derivatives include adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), β-endorphin, γ-MSH, β-lipotropin (β-LPH), β-MSH (in humans), and corticotropin-like intermediate peptide (CLIP).[2][26] ACTH consists of 39 amino acids and lacks disulfide bonds, amidation, or N-terminal acetylation. α-MSH is a 13-amino-acid peptide featuring N-terminal acetylation and C-terminal amidation, which enhance its stability and activity, but no disulfide bonds. β-Endorphin comprises 31 amino acids, with potential N-terminal acetylation in certain tissues but no disulfide bonds or consistent amidation. γ-MSH (specifically γ2-MSH) is a 12-amino-acid peptide without disulfide bonds, amidation, or acetylation. β-LPH is an 91-amino-acid precursor peptide that itself undergoes further cleavage, lacking these modifications. β-MSH is an 18-amino-acid peptide derived from γ-LPH in humans, with N-terminal acetylation and C-terminal amidation. CLIP is a 22-amino-acid peptide derived from the C-terminus of ACTH, lacking modifications. The joining peptide region yields an amidated peptide that forms a homodimer linked by a cysteine bridge in humans.[2][27][28]| Peptide | Amino Acids | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| ACTH | 39 | None (no disulfides, amidation, or acetylation) |

| α-MSH | 13 | N-terminal acetylation, C-terminal amidation |

| β-Endorphin | 31 | Possible N-terminal acetylation |

| γ-MSH (γ2) | 12 | None |

| β-LPH | 91 | None |

| β-MSH | 18 | N-terminal acetylation, C-terminal amidation |

| CLIP | 22 | None |