Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pepin the Short

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

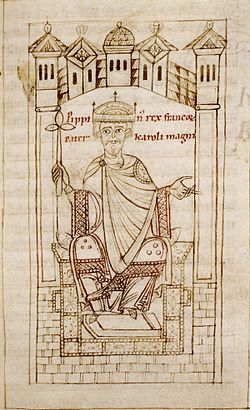

Pepin[a] the Short (Latin: Pipinus; French: Pépin le Bref; German: Pippin der Kurze;[b] c. 714 – 24 September 768) was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.[2]

Key Information

Pepin was the son of the Frankish prince Charles Martel and his wife Rotrude. Pepin's upbringing was distinguished by the ecclesiastical education he had received from the Christian monks of the Abbey Church of St. Denis, near Paris. In 741, after Pepin and his older brother Carloman besieged their half brother Grifo (who did not accept their father's plans for sucession) at Laon and imprisoned him in a monastary, he and Carloman succeeded their father as the Mayor of the Palace; In effect, Pepin reigned over Francia jointly with his elder brother, Carloman. Pepin ruled in Neustria, Burgundy, and Provence, while his older brother Carloman established himself in Austrasia, Alemannia, and Thuringia. The brothers were active in suppressing revolts led by the Bavarians, Aquitanians, Saxons, and the Alemanni in the early years of their reign. In 743, they ended the Frankish Interregnum by choosing Childeric III, who was to be the last Merovingian monarch, as figurehead King of the Franks.[citation needed]

Being well disposed towards the Christian Church and Papacy on account of their ecclesiastical upbringing, Pepin and Carloman continued their father's work in supporting Saint Boniface in reforming the Frankish church and evangelizing the Saxons. After Carloman, an intensely pious man, retired to religious life in 747, Pepin became the sole ruler of the Franks. He suppressed a revolt led by his escaped half-brother Grifo (who was being assisted by his maternal great-uncle Duke Odilo of Bavaria) and succeeded in becoming the undisputed master of all Francia. Giving up pretense, Pepin then forced Childeric into a monastery and had himself proclaimed King of the Franks with the support of Pope Zachary in 751. Not all members of the Carolingian family supported the decision, and Pepin had to put down a revolt led by Carloman's son, Drogo,[citation needed] and again by Grifo.[citation needed]

As King of the Franks, Pepin embarked on an ambitious program to expand his power. He reformed the Franks' legislation and continued Boniface's ecclesiastical reforms. Pepin also intervened in favour of the Papacy of Stephen II against the Lombards in Italy. In the midsummer of 754, Stephen II anointed Pepin afresh,[3] together with his two sons, Charles and Carloman.[4] The ceremony took place in the Abbey Church of St. Denis, and the Pope formally forbade the Franks ever to elect as king anyone who was not of the sacred race of Pepin. He also bestowed upon Pepin and his sons the title of Patrician of Rome.[5] Pepin was able to secure several cities, which he then gave to the Pope as part of the Donation of Pepin. This formed the legal basis for the Papal States in the Middle Ages. The Byzantine Greeks, keen to make good relations with the growing power of the Frankish Empire, gave Pepin the title of Patricius.[citation needed]

In wars of expansion for the Frankish realm, Pepin conquered Septimania from the Umayyad and Andalusian Muslims and defeated them at the siege of Narbonne in 759,[6][7] and proceeded to subjugate the southern realms by repeatedly defeating Waiofar and his Gascon troops, after which the Gascon and Aquitanian lords saw no option but to pledge loyalty to the Franks. Pepin was, however, troubled by the relentless revolts of the Saxons and the Bavarians. He campaigned tirelessly in Germania as well, but the final subjugation of the Germanic tribes was left to his successors.[citation needed]

Pepin died in 768 from unknown causes and was succeeded by his sons Charlemagne and Carloman. Although Pepin was one of the most powerful and successful rulers of his time, his reign is largely overshadowed by that of his more famous son, Charlemagne. [citation needed]

Assumption of power

[edit]Pepin's father Charles Martel died in 741. He divided the rule of the Frankish kingdom between Pepin and his elder brother, Carloman, his surviving sons by his first wife: Carloman became Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia, Pepin became Mayor of the Palace of Neustria. Grifo, Charles's son by his second wife, Swanahild (also known as Swanhilde), demanded a share in the inheritance, but he was besieged in Laon, forced to surrender and imprisoned in a monastery by his two half-brothers.[citation needed]

In the Frankish realm, the kingdom's unity was essentially connected with the king's person. So Carloman, to secure this unity, raised the Merovingian Childeric to the throne (743). Then, in 747, Carloman resolved to enter a monastery after years of consideration.[8] This left Francia in the hands of Pepin as sole mayor of the palace and dux et princeps Francorum.[citation needed]

At the time of Carloman's retirement, Grifo escaped his imprisonment and fled to Duke Odilo of Bavaria, who was married to Hiltrude, Pepin's sister. Pepin put down the renewed revolt led by his half-brother and successfully restored the kingdom's boundaries.

| Carolingian dynasty |

|---|

|

Under the reorganization of Francia by Charles Martel, the dux et princeps Francorum was the commander of the kingdom's armies, in addition to his administrative duties as mayor of the palace.[9]

First Carolingian king

[edit]

As mayor of the palace, Pepin was formally subject to the decisions of Childeric III, who had only the title of king, with no power. Since Pepin had control over the magnates and had the power of a king, he now addressed to Pope Zachary a suggestive question:

- In regard to the kings of the Franks who no longer possess the royal power: is this state of things proper?

Hard pressed by the Lombards, Pope Zachary welcomed this move by the Franks to end an intolerable condition and lay the constitutional foundations for exercising royal power. The Pope replied that such a state of things is not proper. Under these circumstances, the wielder of actual power should be called King. After this decision, Childeric III was deposed and confined to a monastery. He was the last of the Merovingians.

Pepin was then elected King of the Franks by an assembly of Frankish nobles, with a large portion of his army on hand. The earliest account of his election and anointing is the Clausula de Pippino, written around 767. Meanwhile, Grifo continued his rebellion but was eventually killed in the battle of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne in 753.

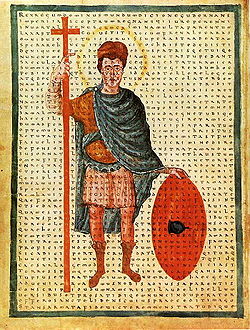

Pepin was assisted by his friend Vergilius of Salzburg, an Irish monk who probably used a copy of the "Collectio canonum Hibernensis" (an Irish collection of canon law) to advise him to receive royal unction to assist his recognition as king.[10] Anointed a first time in 751 in Soissons, Pepin added to his power after Pope Stephen II traveled to Paris to anoint him a second time in a lavish ceremony at the Basilica of St Denis in 754, bestowing upon him the additional title of Patricius Romanorum (Patrician of the Romans). This was the first recorded crowning of a civil ruler by a Pope.[11] As life expectancies were short in those days, and Pepin wanted family continuity, the Pope also anointed Pepin's sons, Charles (eventually known as Charlemagne), who was 12, and Carloman, who was 3.

The significance of the anointment ceremony is visible in that the Pope newly adopted it and was unheard of in Rome. This, together with granting the title of Patrician of the Romans, which was connected to the role of Defensor civitatis (protector of oppressed citizens), meant that Pepin was now designated as the defender of the Church.[12]

Expansion of the Frankish realm

[edit]

Pepin's first major act as King of the Franks was to go to war against the Lombard king Aistulf, who had expanded into the ducatus Romanus. After a meeting with Pope Stephen II at Ponthion, Pepin forced the Lombard king to return the property seized from the Church.[13] He confirmed the papacy in possession of Ravenna and the Pentapolis, the so-called Donation of Pepin, whereby the Papal States were established, and the temporal reign of the papacy officially began.[13] At about 752 he turned his attention to Septimania, a region in southern Gaul that formally belonged to the Visigothic Kingdom.[14] The new king headed south in a military expedition down the Rhône Valley. He received the submission of eastern Septimania (i.e., Nîmes, Maguelone, Béziers, and Agde) after securing count Ansemund's allegiance. Then, the Frankish king went on to conquer the city of Narbonne, which had passed briefly to the Emirate of Córdoba, with the final victory by the Christian Franks in 759.[15][6][7] Eventually, Pepin chased the Muslim Arabs and Berbers away from Septimania and conquered Narbonne in 759,[6][7] after which the city became part of the Frankish Viscounty of Narbonne. Septimania became a march of the Carolingian Empire and then West Francia down to the 13th century, though it was culturally and politically autonomous from the northern France-based central royal government. By the end of the 9th century, the region was renamed as Gothia or Marca Gothica ("Gothic March"). The region was under the influence of the people from the count territories of Toulouse, Provence, and ancient County of Barcelona. It was part of the wider cultural and linguistic region comprising the southern third of France known as Occitania.

However, Aquitaine remained under Waiofar's Gascon-Aquitanian rule and beyond Frankish reach. Duke Waiofar appears to have confiscated Church lands, maybe distributing them among his troops. In 760, after conquering the Roussillon from the defeated Muslims and denouncing Waiofar's actions, Pepin moved his troops over to Toulouse and Albi, ravaged with fire and sword most of Aquitaine, and, in retaliation, counts loyal to Waiofar ravaged Burgundy.[16] Pepin, in turn, besieged the Aquitanian-held towns and strongholds of Bourbon, Clermont, Chantelle, Bourges and Thouars, defended by Waiofar's Gascon troops, who were overcome, captured and deported into northern France with their children and wives.[17]

In 763, Pepin advanced further into the heart of Waiofar's domains and captured major strongholds (Poitiers, Limoges, Angoulême, etc.), after which Waiofar counterattacked and war became bitter. Pepin opted to spread terror, burning villas, destroying vineyards, and depopulating monasteries. By 765, the brutal tactics seemed to pay off for the Franks, who destroyed resistance in central Aquitaine and devastated the whole region. The city of Toulouse was conquered by Pepin in 767, as was Waiofar's capital of Bordeaux.[18] As a result, Aquitanian nobles and Gascons from beyond the Garonne also saw no option but to accept a pro-Frankish peace treaty (Fronsac, c. 768). Waiofar escaped but was assassinated by his frustrated followers in 768.

Legacy

[edit]

Pepin died on campaign in 768 at the age of 54. He was interred in the Basilica of Saint Denis in modern-day Metropolitan Paris. His wife Bertrada was also interred there in 783. Charlemagne rebuilt the Basilica in honor of his parents and placed markers at the entrance.

The Frankish realm was divided according to the Salic law between his two sons: Charlemagne and Carloman I.

Historical opinion[who?] often seems to regard him as the lesser son and lesser father of two greater men, though a great man in his own right. He continued building up the heavy cavalry his father had begun. He maintained the standing army that his father had found necessary to protect the realm and form the core of its whole army in wartime. He not only contained the Spanish Muslims as his father had but drove them out of what is now France and, as important, he managed to subdue the Aquitanians and the Gascons after three generations of on-off clashes, opening the gate to central and southern Gaul and Muslim Spain. He continued his father's expansion of the Frankish church (missionary work in Germany and Scandinavia) and the institutional infrastructure (feudalism) that would prove the backbone of medieval Europe.

His rule was historically significant and greatly beneficial to the Franks as a people. Pepin's assumption of the crown and the title of Patrician of Rome were harbingers of his son's imperial coronation. He made the Carolingians the ruling dynasty of the Franks and the foremost power of Europe.

Family

[edit]Pepin married Leutberga from the Danube region. They had five children. She was repudiated sometime after the birth of Charlemagne, and her children were sent to convents.[citation needed]

In 744, Pepin married Bertrada, daughter of Caribert of Laon. They are known to have had seven children, at least three of whom survived to adulthood:

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Duckett 2022

- ^ Riché 1993, p. 65.

- ^ Doig 2008, p. 110

- ^ Duckett 2022

- ^ R.H.C 1957, p. 133

- ^ a b c d Deanesly, Margaret (2019). "The Later Merovingians". A History of Early Medieval Europe: From 476–911. Routledge Library Editions: The Medieval World (1st ed.). London and New York City: Routledge. pp. 244–245. ISBN 9780367184582.

- ^ a b c d Collins, Roger (1998). "Italy and Spain, 773–801". Charlemagne. Buffalo, London, and Toronto: Palgrave Macmillan/University of Toronto Press. pp. 65–66. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-26924-2_4. ISBN 978-1-349-26924-2.

- ^ Duckett 2022

- ^ Schulman 2002, p. 101.

- ^ Enright 1985, p. ix, 198.

- ^ Kazhdan et al. 1991.

- ^ Ullmann 2013, pp. 67–69

- ^ a b Brown 1995, p. 328.

- ^ Jiménez Garnica, Ana M. (2003) [1999]. "Settlement of the Visigoths in the Fifth Century". In Heather, Peter J. (ed.). The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. Studies in Historical Archaeoethnology. Vol. 4. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. pp. 93–115. ISBN 978-1-84383-033-7.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. chapter 1.

- ^ Petersen 2013, p. 728.

- ^ Petersen 2013, pp. 728–731.

- ^ Tucker 2011, p. 215.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brown, T.S. (1995). "Byzantine Italy". In McKitterick, Rosamond (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, c. 700–c. 900. Vol. II. Cambridge University Press.

- Doig, Allan (2008). Liturgy and architecture from the early church to the Middle Ages. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754652748.

- Duckett, Eleanor Shipley (20 September 2022). "Pippin III". www.britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- Dutton, Paul Edward (2008). Charlemagne's Mustache: And Other Cultural Clusters of a Dark Age. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Enright, M.J. (1985). Iona, Tara, and Soissons: The Origin of the Royal Anointing Ritual. Walter de Gruyter.

- Kazhdan, Alexander P. (Aleksandr Petrovich); Talbot, Alice-Mary Maffry; Cutler, Anthony; Gregory, Timothy E.; Ševčenko, Nancy Patterson (1991). The Oxford dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195046528. OCLC 22733550.

- Lewis, Archibald R. (2010). The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050. The Library of Iberian Resources Online.

- Petersen, Leif Inge Ree (2013). Siege Warfare and Military Organization in the Successor States (400–800 AD): Byzantium, the West and Islam. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-25199-1.

- R.H.C, Davis (1957). A History of Medieval Europe – From Constantine to Saint Louis. Great Britain: Longman. ISBN 0582482089.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Riché, Pierre (1993). The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. Translated by Allen, Michael Idomir. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Schulman, Jana K., ed. (2002). The Rise of the Medieval World, 500–1300: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Press.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2011). A Global Chronology of Conflict. Vol. I. ABC-CLIO.

- Ullmann, Walter (2013). Growth of Papal Government in Middle Ages – Study in Ideological Relation of Clerical to Lay Power. Routledge.

- Bradbury, Jim (2007). The Capetians: Kings of France.

External links

[edit]- Literatur über Pippin den Jüngeren in the German National Library catalogue

- Document by Pepin for Fulda Abbey, 760, "digitalised image". Photograph Archive of Old Original Documents (Lichtbildarchiv älterer Originalurkunden). University of Marburg..

Pepin the Short

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Early Career

Ancestry and Birth

Pepin the Short, also known as Pepin III, was born around 714 in the region of Austrasia, likely at Jupille-sur-Meuse near Liège in the Frankish realm. He was the eldest legitimate son of Charles Martel, the Mayor of the Palace in Austrasia who effectively controlled Frankish military and administrative affairs, and Rotrude (also called Chrotrud or Ruodhaid), a noblewoman from the Hesbaye or Trier region.[3][4] Pepin's paternal lineage traced to the Pippinid (or Arnulfing-Pippinid) family, which had ascended through successive mayors of the palace, positions originally managing royal households but evolving into de facto rulership over the Franks. His grandfather, Pepin of Herstal (Pepin II), had unified Austrasian authority by defeating rival Neustrian factions at the Battle of Tertry in 687, establishing Pippinid dominance despite the persistence of nominal Merovingian kings. These kings, descended from Clovis I, had devolved into ceremonial figures—derisively termed rois fainéants ("do-nothing kings")—due to repeated partitions of the realm among heirs, which fragmented central authority and empowered regional aristocrats and military leaders like the Pippinids.[5][6] The Pippinids' control stemmed from pragmatic military successes and innovations, such as Charles Martel's distribution of church lands as benefices to loyal warriors, which sustained armies without relying on depleted royal treasuries—a causal shift from Merovingian reliance on fixed levies and tolls. Pepin's birth occurred amid ongoing threats, including Umayyad Muslim incursions in Septimania and Aquitaine, and Lombard pressures in Italy, with his father frequently absent on campaigns that culminated in the decisive victory at the Battle of Tours (Poitiers) in 732, halting further Arab expansion into Francia. This environment of persistent warfare and governance necessities provided Pepin early immersion in the martial and administrative roles that defined Carolingian ascendancy.[7]Rise as Mayor of the Palace

Following the death of their father, Charles Martel, on 22 October 741, Pepin and his elder brother Carloman succeeded him as joint mayors of the palace, effectively controlling the Frankish kingdoms of Austrasia, Neustria, and Burgundy through division of administrative and military responsibilities—Pepin overseeing Neustria, Burgundy, and Provence, while Carloman managed Austrasia, Alemannia, and Thuringia.[8][9] This arrangement preserved Pippinid dominance amid the nominal rule of Merovingian kings, whose authority had eroded to mere figureheads reliant on mayoral enforcement for governance.[8] The brothers promptly consolidated power by suppressing internal threats, including a rebellion instigated by their half-brother Grifo, whom they defeated militarily and confined to prevent further challenges to their inheritance.[8] Between 742 and 743, they quelled uprisings among Neustrian nobles and other dissidents, reimposing order through decisive campaigns that underscored the causal primacy of military loyalty and noble alliances over hereditary titles in sustaining Frankish stability.[9] Concurrently, joint expeditions repelled incursions by the Saxons and Alemanni, securing peripheral territories and affirming the mayors' de facto sovereignty derived from battlefield success rather than royal sanction.[9][10] Administrative initiatives under their joint rule included ecclesiastical reorganizations, such as supporting Boniface's efforts to standardize church hierarchies and monastic practices, which bolstered fiscal resources by curbing alienated lands and enhancing revenue collection previously undermined by Merovingian weaknesses.[10] These measures linked effective control of religious institutions to broader realm cohesion, enabling sustained military funding without the fiscal disarray of prior decades.[8] In August 747, Carloman abdicated the mayoralty, driven by personal piety, and withdrew to monastic life after receiving tonsure from Pope Zachary in Rome, an act ratified by Frankish noble assemblies without evident coercion and reflecting the normalized transfer of real power among Pippinid kin.[8] This left Pepin as sole mayor, unopposed in exercising authority across the unified Frankish domains.[9]Ascension to the Throne

Collaboration with Carloman

Following the death of their father, Charles Martel, on October 22, 741, Pepin and Carloman assumed joint authority as mayors of the palace over the Frankish realms, with Pepin administering Neustria and Burgundy in the west while Carloman governed Austrasia in the east.[11] This pragmatic division of responsibilities facilitated coordinated responses to internal challenges, enabling the brothers to maintain Carolingian dominance without fracturing the realm. In 742, they suppressed a Neustrian uprising led by Theudald, a rival claimant supported by dissident nobles and their half-brother Grifo, defeating the rebels and imprisoning Grifo to neutralize familial threats.[12] Carloman concurrently addressed eastern disruptions, including assertions of autonomy by Duke Odilo of Bavaria, who submitted to Frankish overlordship in 743 after campaigns culminating in a confrontation at the Lech River.[13] These actions empirically stabilized the periphery, dividing labor effectively—Pepin on western fronts and Carloman eastward—while avoiding broader civil strife through shared command structures. By 747, amid ongoing consolidation, Carloman abdicated, citing religious motivations but effecting a strategic withdrawal that transferred his territories and authority to Pepin, thereby preventing dynastic rivalry. He journeyed to Rome, received tonsure at Monte Soratte, and established a monastery dedicated to Saint Sylvester before withdrawing further into monastic life.[14] The Frankish nobility endorsed this consolidation at a subsequent assembly, affirming Pepin's unchallenged mayoralty without bloodshed and distinguishing the voluntary internal merger from the later coercive removal of the Merovingian dynasty. This maneuver positioned Pepin for sole rule as papal concerns over Lombard encroachments intensified, underscoring the brothers' earlier collaboration as a foundation for unified Carolingian preeminence.[11]Deposition of the Merovingians and Papal Endorsement

In 751, following his consolidation of authority as mayor of the palace after his brother Carloman's retirement in 747, Pepin III dispatched envoys to Pope Zacharias in Rome to seek endorsement for deposing the last Merovingian king, Childeric III.[15][8] Pepin's query framed the issue causally: whether it was fitting for royal power to reside with the titleholder or with the effective ruler, emphasizing that the former held no substantive authority.[16][17] Zacharias responded affirmatively, ruling that power and title should align, thereby sanctioning the deposition without moral condemnation of the status quo.[16][18] At an assembly of Frankish nobles convened in Soissons in November 751, Childeric III—whose reign since 743 had been nominal—was formally deposed without recorded opposition or mobilization of Merovingian forces.[8][19] His long hair, a Merovingian symbol of kingship, was shorn in a ritual tonsure, and he was confined to the monastery of Saint-Bertin, alongside his son; this act underscored the dynasty's impotence, as no independent noble factions rallied to defend him.[15][19] The nobles, who had long deferred to Pippinid mayors for governance and military leadership, acclaimed Pepin as king, reflecting empirical realities of power distribution rather than adherence to hereditary title alone.[19][20] Historians traditionally critiquing the event as a dynastic usurpation overlook causal evidence of Merovingian decline: since Dagobert I's death in 639, succeeding kings were often minors or short-reigned figures lacking personal armies, fiscal control, or decision-making autonomy, with real authority vested in palace mayors like the Pippinids who managed assemblies, warfare, and alliances.[21] No revolts ensued post-deposition, affirming the transition's alignment with de facto control and the stability Pippinids had provided amid prior civil strife.[20][22] Zacharias's endorsement, while papal, served pragmatic Frankish-papal alignment against Lombard incursions threatening Rome, rather than a divine mandate; the Lombards' persistent aggression, despite partial Catholicization, necessitated a capable Frankish ally, distinct from the subsequent 752 religious anointing by Boniface that invoked Old Testament precedents.[18][15] Modern analyses prioritize this mutual strategic calculus over later Carolingian propaganda vilifying Merovingians to bolster dynastic legitimacy.[23][24]Reign and Military Expansions

Royal Anointing and Internal Consolidation

In response to Lombard incursions threatening papal territories, Pope Stephen II crossed the Alps in late 753 and met Pepin at Ponthion on January 6, 754, where the king received him with deference despite prior oaths to the Lombards.[25] The pope's biographer emphasized Stephen's prostration before Pepin, underscoring the reversal of roles that highlighted the Carolingian's de facto dominance and the papacy's reliance on Frankish military power for causal security.[25] This encounter at Ponthion transitioned to Quierzy by April, where Pepin pledged restoration of papal lands seized by King Aistulf, formalizing an alliance grounded in mutual necessity rather than abstract fealty.[26] The culminating ritual occurred on July 28, 754, at the Basilica of Saint-Denis near Paris, where Stephen anointed Pepin, his wife Bertrada, and sons Charles and Carloman as kings of the Franks and patricians of the Romans.[27] This papal consecration—preceded by Boniface's in 751 but elevated by Roman authority—marked the first such sacramental endorsement of a Frankish ruler, invoking St. Peter as the mystical conferrer of secular power and thereby instituting a precedent for divine-right monarchy.[10] Empirically, the rite transcended mere symbolism by aligning ecclesiastical sanction with Pepin's existing control, countering residual Merovingian legitimacy tied to elective traditions and Salic law interpretations that favored noble consensus over hereditary sacrality; clerical consecration supplanted election as the essential criterion for kingship, as evidenced by subsequent Carolingian coronations.[28] This fusion of ritual and politics empirically facilitated elite unification, diminishing factional resistance by framing opposition as defiance of divine order, distinct from prior reliance on battlefield victories or assembly votes alone. Post-anointing, Pepin secured internal cohesion through targeted political measures, convening Frankish assemblies to extract oaths of loyalty from nobles and redistribute benefices confiscated from Merovingian adherents to Carolingian loyalists, as reflected in surviving charters attesting heightened administrative centralization.[10] These actions prioritized stabilization over expansion, reforming legislation to streamline governance and integrating disparate aristocracies via enforced fealty, which charters indicate bolstered fiscal and judicial efficiency.[26] Initial efforts against Aquitaine's duke Waifer, who withheld homage and retained semi-autonomy, involved diplomatic summons and preliminary confiscations rather than full invasion, aiming to preempt rebellion through loyalty incentives and targeted dispossession.[19] Such consolidation empirically reduced internal threats, enabling Pepin's regime to transition from mayoral shadow rule to overt monarchy without widespread noble defection.Campaigns Against the Lombards

In 751, Lombard King Aistulf captured Ravenna, the final Byzantine stronghold in northern Italy, along with surrounding territories in the exarchate and Pentapolis, thereby extinguishing organized Byzantine authority in the region and intensifying pressure on papal holdings.[29] This conquest prompted Pope Zacharias to seek Frankish intervention, though direct military action followed under his successor, Stephen II, who appealed to Pepin amid Aistulf's threats to Rome itself by 753.[29] Pepin's response was framed as a defense of papal sovereignty against Lombard expansionism, which endangered key Christian sees and the remnants of Roman administrative legacy in Italy.[19] Following Stephen II's journey to Francia and Pepin's royal anointing in July 754 at Quierzy-sur-Oise, Pepin mobilized Frankish forces and crossed the Alps into Italy that autumn.[24] He advanced rapidly, defeating Aistulf's armies in engagements near Piacenza and besieging the Lombard king at Pavia, the royal capital. Under duress from the siege, Aistulf capitulated in early 755, agreeing in a treaty to withdraw from Ravenna and restore the exarchate and Pentapolis to papal control, with Frankish hostages exchanged as guarantees.[30] However, Aistulf soon violated the terms, resuming aggression by besieging Rome in January 756 and refusing to relinquish the territories.[31] Pepin launched a second expedition in 756, again traversing the Alps to confront Aistulf, whose forces scattered before the Frankish advance.[19] Renewed pressure, including threats to Pavia, compelled Aistulf to surrender the disputed cities' keys and charters to papal envoys, effectively transferring control of Ravenna, Rimini, Pesaro, and other exarchate holdings to the papacy by mid-756.[32] These campaigns halted Lombard territorial gains in central Italy, bolstering papal temporal independence from both Lombard and residual Byzantine claims, though they imposed logistical strains on Frankish resources through repeated Alpine crossings and sieges.[19] Unlike Pepin's other military efforts, these interventions were uniquely tied to direct papal entreaties, prioritizing the preservation of ecclesiastical authority over broader conquest.[24]Conquests in Aquitaine and Septimania

Pepin's campaigns in Septimania extended the Frankish containment of Umayyad expansion initiated by his father Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours in 732, targeting the remaining Muslim-held coastal enclave north of the Pyrenees. In 759, following the conquest of Roussillon, Pepin besieged and captured Narbonne, the principal stronghold of Umayyad governors in the region, compelling its surrender after a prolonged siege and expelling Islamic forces from the area.[33][34] This victory marked the effective end of Umayyad control in Septimania, with Franks securing fortified positions like Narbonne and integrating the Gothic population under Frankish law while preserving local customs to facilitate administration.[35][36] Turning to Aquitaine, Pepin launched punitive expeditions against Duke Waifer starting in 760, prompted by Waifer's seizure of church properties and resistance to Frankish overlordship in the semi-autonomous duchy. Pepin's forces ravaged key sites including Toulouse and Albi, employing scorched-earth tactics such as burning villas, destroying vineyards, and depopulating monasteries to induce famine and undermine guerrilla resistance.[37][3] By 765, these brutal measures eroded Waifer's support base, enabling Frankish advances that captured northern Aquitanian strongholds like Bourbon and Clermont, progressing southward to the Gironde River by 768.[19][3] Waifer's death in 768 concluded the campaigns, allowing Pepin to annex Aquitaine fully into the Frankish realm and suppress lingering revolts, thereby consolidating central authority over a region long prone to independence. While contemporary accounts note the severity of Pepin's methods, such strategies proved empirically effective in breaking decentralized resistance, contrasting with more diplomatic approaches in other theaters and prioritizing territorial integrity over immediate humanitarian concerns.[9][38] These southern victories reinforced the Frankish frontier against Islamic incursions, laying groundwork for Charlemagne's Iberian forays while addressing internal fragmentation through decisive military dominance.[39]Relations with the Church and Papacy

Alliance Formation and Papal Support

In 750, Pepin dispatched envoys to Pope Zacharias inquiring whether it was advisable to retain kings lacking real authority, to which the pope replied affirmatively that power ought to confer the title of king, thereby endorsing Pepin's deposition of the Merovingian Childeric III and his own elevation in 751.[19] This exchange marked the initial diplomatic overture, rooted in the papacy's interest in a capable Frankish protector amid Lombard encroachments on Roman territories, as Zacharias viewed the Carolingian ascendancy as a bulwark against regional instability.[18] The alliance deepened following the Lombard king Aistulf's seizure of Ravenna and threats to Rome in 751–752, prompting Pope Stephen II—Zacharias's successor—to traverse the Alps in late 753, the first such papal journey north of the mountains.[24] Stephen met Pepin at Ponthion on January 6, 754, where, in response to the pope's pleas, Pepin swore a solemn oath to defend the Roman Church, St. Peter's patrimony, and the city of Rome against the Lombards and any adversaries, framing the bond as a reciprocal pact of mutual security.[40] This commitment, distinct from later territorial grants, emphasized strategic interdependence: the papacy offered ideological legitimacy through anointing rites at Quierzy and Saint-Denis in 754, while Pepin pledged military safeguarding, evidenced by his subsequent interventions that deterred further Lombard aggression and elevated Frankish influence in Italian affairs.[25] Pepin's fulfillment of the oath via expeditions in 754 and 756 against Aistulf demonstrated the alliance's operational quid pro quo, as recorded in contemporary papal annals like the Liber Pontificalis, which detail the king's enforced retreats of Lombard forces without attributing ulterior motives beyond defensive reciprocity.[25] Empirically, this church-state symbiosis yielded causal advantages for both: the papacy gained a reliable deterrent against existential threats, preserving ecclesiastical autonomy and cultural continuity in Italy; for the Franks, papal endorsement conferred sacral authority, bolstering internal cohesion and external prestige amid rival claimants, as seen in the unchallenged consolidation of Carolingian rule post-754.[40] While some historiographical views later critiqued the arrangement as fostering papal dependency, the contemporaneous outcomes—Lombard concessions and Frankish dynastic stability—substantiate its pragmatic efficacy over theoretical autonomy concerns.[24]The Donation of Pepin

Following the second Frankish campaign against the Lombards in 756, which compelled King Aistulf to submit and relinquish territorial gains, Pepin the Short issued a charter at Quierzy confirming the grant of central Italian territories to Pope Stephen II. These encompassed the former Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna— including the cities of Ravenna, Forlì, Forlimpopoli, Cesena, Rimini, Pesaro, and Cagli—along with the Pentapolis (cities such as Ancona, Numana, and Osimo) and portions of the Duchy of Spoleto.[41] A subsequent confirmation occurred in 757 at Compiègne, solidifying the transfer and establishing de facto papal sovereignty over these lands, previously contested between Lombards and a receding Byzantine presence.[42] The donation fulfilled promises exchanged during Pope Stephen II's 753–754 visit to the Frankish court, where Pepin pledged military aid in return for papal anointing and legitimacy for his dynasty, while the pope sought protection from Lombard encirclement of Rome.[41] Contemporary papal sources, such as the Liber Pontificalis, portray the act as a voluntary pious gift, emphasizing Pepin's role as a divinely favored defender of the Church against Arian-influenced Lombard aggression.[43] No primary evidence indicates coercion of Pepin, whose strategic interests aligned with creating a buffer state under papal control to stabilize Frankish influence in Italy; however, Byzantine protests highlighted the donation's overreach onto imperial claims, underscoring its unilateral nature from a Frankish-papal perspective.[41] Causally, the grant birthed the Papal States as a territorial entity, enabling the papacy to administer revenues, muster defenses, and assert independence from both Lombard and Byzantine overlords, thereby preventing the consolidation of hostile powers around Rome.[42] This autonomy empirically forestalled Lombard reconquest in the late 8th century and indirectly fortified Christendom's Italian frontier amid emerging Islamic pressures from the south, as papal control facilitated alliances and resource allocation verifiable in subsequent Carolingian-papal correspondence.[44] Yet, it sowed tensions by vesting the papacy with secular authority, fostering later investiture controversies where clerical temporal claims clashed with monarchical prerogatives, as critiqued in medieval reformist writings attributing papal overreach to this origin.[43]Administration and Domestic Rule

Governance Structure

Pepin's administrative framework emphasized a decentralized system grounded in local counts, who served as royal agents responsible for justice, taxation, and military mobilization within their counties, drawing on established Frankish customs to incentivize loyalty through land grants rather than rigid central control. To monitor these officials and extend royal oversight, he employed missi dominici—elite envoys, often paired lay and clerical figures from distant regions to avoid local biases—who inspected districts, enforced decrees, resolved disputes, and relayed intelligence on governance and threats, thereby stabilizing the realm after Merovingian fragmentation.[45] Retaining Germanic traditions, Pepin convened assemblies such as the Marchfield (Placitum Generalis), annual gatherings of nobles, clergy, and freemen held between March and May, where laws were debated, justice dispensed, and policies aligned with elite consensus, helping to legitimize his rule and curb aristocratic factionalism through participatory decision-making.[46] Pepin advanced uniformity by issuing capitularies and reforming Frankish legislation, standardizing legal codes and administrative practices to address inconsistencies from prior eras, while suppressing revolts—such as those by Grifo and Aquitainian nobles—to consolidate power and integrate peripheral regions via loyal appointees, fostering a loyalist network over autonomous magnates.[46][2]Ecclesiastical Policies

Pepin continued the ecclesiastical reforms begun under his family's mayoralty, particularly those advanced by Saint Boniface, which sought to impose canonical order on the fragmented Frankish church by organizing dioceses, enforcing clerical celibacy, and regularizing monastic discipline according to Benedictine standards.[10] These efforts addressed persistent issues of laxity and local autonomy that had undermined religious uniformity, providing a stabilizing framework that aligned ecclesiastical structures with emerging Carolingian governance.[47] A key aspect of Pepin's domestic policies involved promoting the Roman liturgy to supplant diverse Gallican variants, which varied regionally and incorporated non-Roman elements potentially conducive to doctrinal divergence.[48] Around 760, he issued decrees facilitating the introduction of Roman chant, supported by influential bishops, to standardize worship practices across the realm and reinforce ties to orthodox Roman traditions.[48] This liturgical unification, while asserting royal oversight, empirically contributed to greater cohesion by reducing ritual fragmentation that could exacerbate political divisions among Frankish elites and populace remnants of pagan influences. Pepin convened multiple synods during his reign to enforce disciplinary reforms, focusing on clerical conduct and church administration rather than external doctrinal threats.[49] These assemblies, building on earlier councils like those of 742–744, promulgated capitularies that curtailed abuses such as simony and lay interference in bishoprics, thereby bolstering episcopal authority as a counterweight to unruly nobility while maintaining the king's ultimate supervision.[10] Such measures fostered a balanced church-state symbiosis, where ecclesiastical loyalty reinforced monarchical legitimacy without full subordination, seeding the cultural and educational revival later expanded under Charlemagne.[24]Family, Death, and Succession

Marriages and Children

Pepin the Short married Bertrada of Laon, daughter of Count Charibert of Laon, around 741, a union that reinforced Carolingian ties to the Laon nobility, whose lineage connected back to Pepin's uncle Martin of Laon through Charibert.[50][51] This marriage provided dynastic stability amid the high infant and child mortality rates of the era, ensuring multiple heirs to perpetuate Carolingian rule without reliance on extramarital unions, as Pepin maintained monogamy throughout his life.[52] Bertrada bore Pepin at least eight children, including three sons and five daughters, though not all survived infancy or reached maturity.[53] The two sons who did were Charles (later Charlemagne), born circa 742, and Carloman, born in 751; these heirs were central to the continuity of Carolingian power, with Charles ascending as co-king after Pepin's death.[50][12] Daughters included Rotrude (born circa 744, died young), Gisela (born circa 757, later abbess of Chelles), and possibly Adelheid and others whose records are less certain but indicate Bertrada's role in producing a broader network of alliances through betrothals.[53] No illegitimate children are attested for Pepin, distinguishing his family structure from the more plural unions common among Frankish elites for securing succession in an age of frequent early deaths.[52]| Child | Birth Year (approx.) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Charles (Charlemagne) | 742 | Eldest surviving son; succeeded as king.[50] |

| Rotrude | 744 | Daughter; died in childhood.[53] |

| Carloman | 751 | Second surviving son; co-ruled briefly with Charlemagne.[50] |

| Gisela | 757 | Daughter; became abbess.[53] |

| Others (e.g., Adelheid, Liutarde) | Varied | Daughters with uncertain survival or roles; contributed to diplomatic ties.[53] |