Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Occitania

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

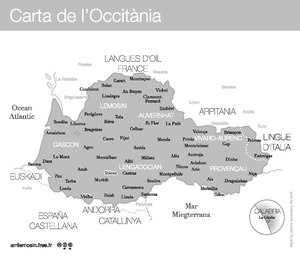

Occitania[a] is the historical region in southern Europe where the Occitan language was historically spoken[1] and where it persists today as a local dialect. This cultural area roughly encompasses much of the southern third of France (except the French Basque Country and French Catalonia) as well as part of Spain (Aran Valley), Monaco, and parts of Italy (Occitan Valleys).

Occitania has been recognized as a linguistic and cultural concept since the Middle Ages. The territory was united in Roman times as the Seven Provinces (Latin: Septem Provinciae[2]) and in the Early Middle Ages (Aquitanica or the Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse,[3] or the share of Louis the Pious following Thionville divisio regnorum in 806[4]).

Currently, the region has a population of 16 million, and between 200,000 and 800,000[5][6] people are either native or proficient speakers of Occitan.[7] More commonly, French, Piedmontese, Catalan, Spanish and Italian are spoken. Since 2006, the Occitan language has been an official language in Catalonia, which includes the Aran Valley, where Occitan gained official status in 1990.

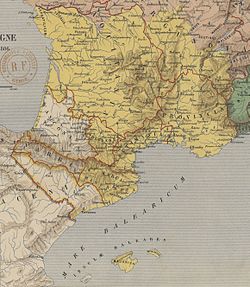

At the time of the Roman empire, most of Occitania was known as Aquitania.[8] The territories conquered early were known as Provincia Romana (see modern Provence), while the northern provinces of what is now France were called Gallia (Gaul). Under the late Roman empire, both Aquitania and Provincia Romana were grouped in the Seven Provinces or Viennensis. Provence and Gallia Aquitania (or Aquitanica) have been in use since medieval times for Occitania (i.e. Limousin, Auvergne, Languedoc and Gascony).

The historic Duchy of Aquitaine should not be confused with the modern French region called Aquitaine: this is a reason why the term Occitania was revived in the mid-19th century. The terms "Occitania"[9] and "Occitan language" (Occitana lingua) appeared in Latin texts from as early as 1242–1254[10] to 1290[11] and during the early 14th century; texts exist in which the area is referred indirectly as "the country of the Occitan language" (Patria Linguae Occitanae). The name Lenga d'òc was used in Italian (Lingua d'òc) by Dante in the late 13th century. The somewhat uncommon ending of the term Occitania is most likely from a French clerk who joined the òc [ɔk] and Aquitània [ɑkiˈtanjɑ] in a portmanteau term, thus blending the language and the land in just one concept.[12]

On 28 September 2016, Occitanie became the name of an administrative region that merged the previous regions of Midi-Pyrénées and Languedoc-Roussillon;[13] it is a small part of Occitania.

Geographic extent

[edit]

The extent of Occitania may vary according to the criteria used:

- Based on a geolinguistic definition, Occitania is the area of Occitan language as surveyed at the end of the 19th century.[14][15] The formerly Occitanophone regions are not included.[16]

On the other hand one always speaks Occitan in the French Basque Country[17][18] and in the Catalan Countries (the Val d'Aran and the Fenolheda), and internal allophone enclaves (Petite Gavacharie of Poitevin-Saintongeais language, ancient Ligurian enclaves of eastern Provence, the quasi-Ligurian-Occitan enclave of Monaco ...). This leads to variations in whether small internal or external enclaves are taken into account.[19] The definition of a contiguous and compact Occitan-speaking territory is currently the most widespread.

- Occitanian culture flourished in the High Middle Ages. Many writers, poets, and exponents in the troubadour movement used Occitan as their language of choice, and their works prominently featured courtly love as well as, at times, ideas of religious and social tolerance.[20] According to this definition taken up by historians and anthropologists,[21] the domain is extended north to the Loire including former Occitanophone regions[22] (Aguiaine, Boischaut, Bourbonnais, etc.).

Northern Italy and the Catalan Countries were also homes of troubadour using the Koiné Occitan literary. In the same way, the Basque Country and Aragon benefited from Occitan stands, old or newer, which notably gave rise to the appearance of an Occitan dialect south of the Pyrenees. We can also note the historical use of an Occitan scripta as official language.[23][24][25]

The name Occitanie appeared in the Middle Ages on the basis of a geographical, linguistic and cultural concept, to designate the part of the French royal domain speaking the langue d’oc.[26]

Its current definition is variable. In the most common usage, Occitania designates the territory where the Occitan has remained in use until today,[27][28][29] within the limits defined between 1876[30] and the 20th century.[31] If Occitan language and culture are almost always associated with it,[27][28][29][32] we also find references to a common history,[32][33] an ethnic group,[32][33] a homeland,[34][35] to a people[36][37][38][39][40] or to a nation.[41][42][43][44] The first sociological study in the Occitan language to learn how the Occitan define themselves was started in 1976.[45] The survey shows that the Occitan reality is defined by language for 95% of people, culture (94%), characterization by a common history (69%), an ethnic group (50%), a nation (20%).[32] Occitania, as defined by the modern Occitan linguistic territory, covers most of the current Southern France, the Alpine valleys of the Western Piedmont, in Italy, Val d'Aran in Spain and Monaco[46][47] an area of approximately 190,000 km2. It had about fifteen million inhabitants in 1999[48] with about 20% inhabitants born outside the territory[49] and about 20% of natives who left.[50] On the other hand, in the absence of a linguistic census, we only imperfectly know the number of speakers of Occitan.[51]

If the preceding notions are generally limited to the modern linguistic boundaries of Occitan, this term can also be used to designate a larger territory. The term "Occitania" becomes commonplace more and more in the vocabulary of scientists.[21] It is used particularly in a historical sense and anthropological by designating a region extending north to the Loire, ignoring contemporary linguistic boundaries.[22] In a book written by experts in medieval history, are included in Occitania of the year 1000 both the provinces of the north (now mainly in Poitou-Charentes) and Catalonia (without the Balearic Islands and the Valencian country) – p. 484.[52] The seven-pointed star, adopted as emblem by the Felibritge symbolized the seven provinces of Occitania, one of which was Catalan.[53][dubious – discuss] Occitanie is indeed divided by this association into seven maintenances (sections) of which one was that of Catalonia-Roussillon.

In 2016, the name Occitanie is used for the French administrative region Languedoc-Roussillon-Midi-Pyrénées which is located on part of the traditional Occitania and includes the Roussillon.

Toponymies

[edit]Occitania comes from the medieval Latin Occitania[b]. The first part of the name, Occ-, comes from Occitan òc and the expression langue d'oc, in Italian lingua d'oc. It is an appellation promoted by Dante Alighieri of Occitan by the way of saying "yes" in Old Occitan-Catalan; as opposed to the "langue de si" (Italian) and the "langue d'oïl" (Old French). The ending -itania is probably an imitation of the name [Aqu] itania (Aquitaine). The term Occitania is a synonym for Languedoc and the Mediterranean coast in the Middle Ages.[54]

The first attestation of the use of Occitanie in French dates from 1556.[55][56][57] The first certificate of Occitania in Italy dates 1549.[58] In German, the word Occitania was found in 1572.[59]

All of the Occitan language countries have had various designations throughout history. The word Occitania has been the subject of whimsical etymologies (for example, Languedoc was formerly understood as "land of the Goths" or "language of the Goths"[60]), as well as the rapprochement to the Occitan language exemplified in the names of the regions Languedoc and Occitania, we find in La Minerve Française, a collective work published in Paris in 1818, a history of name-changes of the provinces which reveals the word Occitanie to be a doublet of the word Occident formed in the Lower Empire, giving it the original meaning of "western regions",[61] and not a region where (necessarily) the Occitan language was spoken.

-

Testament of Lancelot of Orgemont, 1286. The installation of a real Parliament in Toulouse in 1273 chaired by a certain Lancelot d'Orgemont is disputed.[62] The original of the document presented here could date from the 15th century.

-

Entry oucitanìo in The Treasure of Felibritge of Frederic Mistral

-

Pars occitana in a book printed in Latin in 1530.

Like the Occitan language, Occitania has been designated under various successive names.[63] The terms are not exclusive: one can find authors who use different terms in the same time period. Occitania or Pays d'Oc are the most frequently used terms today. However the term Provence is still used when the Felibritge sing the Copa Santa for example during the annual festival of Estello.

- Dioecesis Viennensis (Diocese de Vienne) et Dioecesis Septem Provinciarum (diocesis of the Seven provinces), under Diocletian and Constantine during a division of the Roman Empire, Gaul is divided into dioceses and that of Vienne has its border on the Loire river, bypasses the Central Massif and passes the Rhône between Lyon and Vienne.[64] This is the beginning of the bipartition between Occitan language and langue d'oil.

- Kingdom of Aquitaine: in 781, Charlemagne creates a new kingdom of Aquitaine and names his son Louis the Pious to his head. This new state included the Aquitaine properly speaking (region between Garonne and Loire and the central Massif) as well as the Vasconia. In 806, Charlemagne shares his empire. Louis the Pious receives in addition to Aquitaine the Marca Hispanica, Septimania and Provence.

- Proensa/Proença (old Occitan forms of Provence) and Prouvènço/Provença (Occitan modern forms of Provence), from the Latin Provincia which originally designated the Roman Province is used from the 11th century: all countries of Occitan language (also called Provençal language) of the south of the Loire. The term Provence is still used in its general sense by the Felibritgists.

- Great Provence according to Palestra, Centenary of the Catalan Renaixença.[65]

- Patria romana.[66]

- Lingua Occitana (Occitan language) or Pars occitana (Part of oc) to designate the new royal territories conquered south of the Loire. Occitania was created in Latin by the Capetian administration with the combination of the particle 'Oc/òc' [ɔk] (yes, in Occitan) and of the 'Aquitania/Aquitània' [ɑkitanjɑ] (Aquitaine). Appeared in the 13th century,[67] this term served, after the annexation of almost all the countries of the South by France, to designate only the Languedoc.

- Respublica Occitania (Occitania Republic) during the 14th century.[68]

- Romania (Roumanío), in reference to the medieval usage of calling Occitan the roman.[69]

- Homeland of the Occitan language (Latin patria linguae occitanae), in the official texts of the Kingdom of France from the 14th century.

- Provinces of the Union or United Provinces of the South: in February 1573 the huguenots and the moderate Catholics create a federal republic where each province enjoys a great autonomy vis-a-vis the central power.[70]

- Gascony after the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, "the general name of Gascony or Gascons is used to refer to the countries and peoples to the left side of the Loire where still speaks the old Provençal".[71] Used mainly from the access to the throne of France of Henri IV (1589) and until the French Revolution.[72]

- Reputed foreign provinces of the south of France since the middle of the 17th century at the end of the 18th century

- Occitania in the Diderot Encyclopaedia.[73]

- Occitanie (in the sense of all the Occitan languages): in 1732 in the collection of Capetian laws of Shake Secousse,[74] in 1878, in the Treasure of the Felibritge, in 1911 in the Statutes of the Felibritge;[75] in 1927, Estieu and Salvat founded the College of Occitania.[76]

- Midi: is a vague geographical notion indicating in a rather imprecise way the regions of Occitan dialects of Southern France.

- Southern France: is another vague geographical name indicating in a rather imprecise way the regions of Occitan dialects of Southern France.

- Pays d'Oc: appeared in the 19th century under the impetus of Frederic Mistral,[77] taken over by Antonin Perbòsc four years later.

- Estate of Oc: neologism appeared at the end of the 20th century among supporters of several Occitan languages.

The term "Occitania" now covers a linguistic region. This meaning was used in medieval times attested since 1290.[78] On 29 May 1308, during the Council of Poitiers, it appears that the king of France was declared to reign over two nations: one of lingua gallica and the other of lingua occitana. This partition between Occitan language and langue d'oïl in the Gallo-Roman space is very ancient since it started with Romanisation itself. In 1381, the King Charles VI of France considered that his kingdom comprised two parts: the country of langue d'oc, or Occitania, and the oil-language country or Ouytanie "Quas in nostro Regno occupare solebar tam in linguae Occitanae quam Ouytanae".[79] "Occitania" remained in force in the administration until the French Revolution of 1789. It was taken up again in the 19th century by the literary association of Felibritge[75] then it is again claimed since the 20th century, especially since the end of the 1960s. According to Frédéric Mistral's dictionary "Treasury of Felibritge", the term Occitania is sometimes used by scholars to describe Southern France in general but mainly for the former province of Languedoc.

Historiography of the Occitania concept

[edit]The langue d'oc is a territorialized language, that is to say, spoken mainly on a territory whose boundaries can be described. This part attempts to describe the origins of the Occitanie concept, the different names that this territory has taken and the creation of the modern concept of Occitania.

A unique object of study: d'oc culture

[edit]The speakers of the Occitan language do not use a single meaning of their language because Occitan is not a monolithic language with for example a single dictionary where each speaker finds exactly their vocabulary, but a juxtaposition of dialects. Also, many studies have focused on the differences between Provençal, Languedoc, etc. We must also remember the many common features of the Occitan cultural space, which are generally considered partisans.

The consciousness of a common culture

[edit]Robert Lafont develops this idea in the introduction of the "History and Anthology of Occitan Literature".[80] The reference to troubadours is essential. This socio-linguistic argument is modulated according to the authors but it is accepted by all the current scholarship, including the authors who speak of "domain d'oc", since by definition, their study of the d'oc domain rests on the consciousness of the existence of a common culture.

Intercomprehension

[edit]The different speakers of the language share many common traits (tonic accentuation, close vocabulary, frequent use of the subjunctive, etc.) that allow mutual understanding. For Occitanists, this intercomprehension means that Occitan is one language; for others, it means that these languages are very close but all agree that the speakers in this defined space understand each other.

Common social characteristics

[edit]The social characteristics of Occitania are not eternal and intangible because factors of endogenous mutations[81] and European influences, especially of Northern France, can blur these social peculiarities.[82]

The best studied example is that of Roman Law which is better maintained in the Occitan Early Middle Ages society than in Northern France thanks to the promulgations of Visigoth and Burgundians laws.[83] From the mid-11th century, the teaching of the Corpus Juris Civilis taken shortly after Bologna in the universities of Toulouse, Montpellier, Avignon, Perpignan... will promote a massive renaissance of Roman Law in Occitania.

With regard to education: Pierre Goubert and Daniel Roche write, to explain the low literacy in Occitania in the 18th century, that there exists in these territories a confidence maintained in the old vulgar languages.[84] The relations to education are today completely reversed between Northern and Southern France thanks to the anthropological imprint of the family strain.[85][86]

From a demographic point of view, the influence of the family was still felt in 2007 because of the small number of families with many children.[87]

In politics, many debates have also taken place around the expression Red Southern coined by Maurice Agulhon[88] to find out if the "pays d'oc" was more "republic" than the northern half of France. Emmanuel Todd analyzing the regions that voted for Jean-Luc Mélenchon, calling himself a "Republican" in the 2012 presidential elections, declares that "what is obvious is his general inscription in the Occitan family[...] that loves vertical structures, the state or the church."[89]

Finally, for André Armengaud,[90] these common social characteristics make it possible to write a historical synthesis. But since 1979, no other "History of Occitan" has been undertaken.

The appearance of the modern concept of Occitania

[edit]

If the term Occitania appeared in French from the mid-16th century,[91][92] then in 1732 in a collection of laws of the ancien régime,[93] it only becomes current at 19th century. Thus, the duke of Angoulême conspired with a view to the establishment of a Kingdom of Occitania[94] or of a Vice-Royalty of Occitania[95] at the time of the Restoration. The term was popularized by the publications of Raynouard and Rochegude, and known in its contemporary sense by the English historian Sharon Turner.[96]

It appeared in the Treasury of Felibritge and in the statutes of this organization in 1911.[97] In the Interwar period, a Felibritgan school, the Escòla Occitana was created in 1919 in the Toulousean Languedoc. The Institute of Occitan Studies was born in 1930. These initiatives (as well as others) remain closely linked, notably because of the dual membership of their main animators at Felibritge.

After the Second World War, the creation of the Institute of Occitan Studies was presided over by a resistant (at a time when the Felibritge like the SEO were tainted by lawsuits of collaboration), but above all its action in terms of linguistic reform, particularly its desire to adapt the classical norm to Provençal, marked a break with a large fraction of the Felibritge[98] François Fontan created the first overtly Occitan nationalist party in 1959.

In France, Occitania has been confronted with a problem of recognition of Occitan since 1992; the French is the only "language of the Republic". In 1994, it was made compulsory in the public space (places of commerce and work, public transport, etc.) and in the administration (laws, regulations, documents, judgments, etc.).[99]

In 2015, with the prospect of creating a large region gathering "Midi-Pyrénées" and "Languedoc-Roussillon",[100] the name "Occitanie" came at the head of an online survey organized by the regional press (23% of the 200,000 voting, in front of "Occitanie-Pays catalan" 20%). Note, however, a variable support rate depending on the geographical origin of the voters.[101] As part of the territorial reform, a consultation on the name of the region, organized by the Regional Council Languedoc-Roussillon-Midi-Pyrénées took place in spring 2016 to give a name to the new region regrouping Midi-Pyrenees and Languedoc-Roussillon. Occitanie came first (44.90% of the vote), with 91,598 voters. Second was Languedoc-Pyrenees with 17.81% of the votes, then Pyrenees-Mediterranean (15.31%), Occitanie-Catalan Country (12.15%) and finally Languedoc (10.01%). This new region was renamed Occitanie (with the subtitle Pyrenees-Mediterranean), according to the vote of the regional councillors on 24 June 2016, and after final validation by the Government of France and Conseil d'État.

Distinction between Occitania and Catalonia

[edit]Despite the historic and political dependencies between the 10th and 13th centuries that eventually led to the creation of a common Occitan-Catalan cultural environment during Middle Ages,[102] neither the Principality of Catalonia nor the Catalan Countries have ever been part of Occitania.[103] On the contrary, from the 11th century the Catalan expansion towards the Occitan regions of Languedoc and Provence (through family ties of feudal nobility) gave rise to a long-term confrontation between the countal dynasties of Barcelona and Toulouse, but finally they had to ally against the Cathar Crusade promoted by France and the Papacy in the beginning of the 13th century.[102][104] The great defeat resulting from the Battle of Muret (1213) and the subsequent Treaty of Corbeil (1258) ratified the loss of Catalan influence in Occitania and its gradual replacement by the French dynasty of the House of Capet.[105]

Regarding to linguistic affinity and closeness, after some early Romance-language scholars considered them to be the same language,[106] Catalan intellectuals (among them Pompeu Fabra and Joan Coromines) solemnly proclaimed in a 1934 manifesto that Catalan was a distinct language from Occitan,[107] as established by the common consensus of current scientific linguistics.[108]

Moreover, the Parliament of Catalonia passed in 2015 a law recognizing Aran Valley's "national identity", understood as an "Occitan national reality" apart from the Catalan nation.[109]

Geography

[edit]

Occitania includes the following regions:

- The southern half of France: Provence, Drôme-Vivarais, Auvergne, Limousin, Guyenne, Gascony, southern Dauphiné and Languedoc. French is now the dominant language in this area, where Occitan is not recognized as an official language.

- The Occitan Valleys in the Italian Alps, where the Occitan language received legal status in 1999. These are fourteen Piedmontese valleys in the provinces of Cuneo and Turin, as well as in scattered mountain communities of the Liguria region (province of Imperia), and, unexpectedly, in one community (Guardia Piemontese) in the region of Calabria (province of Cosenza).

- The Aran valley, in the Pyrenees, in Catalonia where Occitan has been an official language since 1990 (status granted by the partial autonomy of Aran Valley, then confirmed by the Catalan Statute)

- The Principality of Monaco (where Occitan is traditionally spoken beside Monégasque).

Occitan or langue d'oc (lenga d'òc) is a Latin-based Romance language in the same way as Spanish, Italian or French. There are six main regional varieties, with easy inter-comprehension among them: Provençal (including Niçard spoken in the vicinity of Nice), Vivaroalpenc, Auvernhat, Lemosin, Gascon (including Bearnés spoken in Béarn) and Lengadocian. All these varieties of the Occitan language are written and valid. Standard Occitan is a synthesis which respects soft regional adaptations.

Catalan is a language very similar to Occitan and there are quite strong historical and cultural links between Occitania and Catalonia.

Historic regions

[edit]The regions of Ancien Régime that make up Occitania are the following: Auvergne (Auvèrnhe), Forez (west and south fringe), Bourbonnais (southern half), Couserans (Coserans), Dauphiné (southern half), County of Foix (County of Fois), County of Nice (County of Nissa), Périgord (Peiregòrd), Gascony, Guyenne (Guiana), Languedoc (Lengadòc), Angoumois (eastern end), Limousin (Lemosin), Poitou (Poetou) (southeastern extremity), La Marche (la Marcha), Provence (Provença), Comtat Venaissin (lo Comtat Venaicin), Velay, Vivarais (Vivarés).

Traditional Occitan Provinces (currently in France):

- Béarn [Bearn] (Pau) – 6,800 km2 (est.)

- Guyenne [Guiana] & Gascony (Bordeaux) – 69,400 km2 (est.)

- Limousin [Lemosin] (Limoges) – 9,700 km2 (est.)

- La Marche (Limousin) [la Marcha] (Guéret) – 7,600 km2 (est.)

- Auvergne [Auvèrnhe] (Riom) – 19,300 km2 (est.)

- Languedoc [Lengadòc] (Toulouse) – 45,300 km2 (est.)

- Dauphiné (Grenoble) – 8,500 km2 (est.)

- County of Nice [County of Nissa] (Nice) – 3,600 km2 (est.)

- Provence [Provença] (Aix-en-Provence) – 22,700 km2 (est.)

- Comtat Venaissin [lo Comtat Venaicin] (Carpentras) – 3,600 km2 (est.)

- County of Foix [County of Fois] (Foix) – 3,300 km2 (est.)

X. Bourbonnais (southern half) – approx. 3,200 km2 (est.)

Administrative divisions in France

[edit]The administrative regions covering Occitania are the following: Occitanie region (except the Pyrénées-Orientales where a majority speak Catalan, although the Fenouillèdes region, in the North-West of the department, that is to say of Occitan language and culture), Nouvelle-Aquitaine (except the peripheries where one speaks basque, poitevin and saintongeais), Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (in the southern half, namely almost all the Drôme and the Ardèche, the southern Isère and some fringes of the Loire) and Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur. In the Centre-Val de Loire Occitan is spoken in some communes in southern Cher and Indre.

Geographical boundaries

[edit]The geographical delimitation of Occitania most commonly accepted was specified between 1876—beginning of research on the linguistic boundaries[110]—and the 20th century. Occitania roughly covers a southern third of France (commonly known as Midi, including Monaco), the Occitan Valleys and Guardia Piemontese, in Italy, as well as the Val d'Aran, in Spain.

The practice of Occitan is not the same uniformly throughout the territory. In addition, there is a linguistic transition area in the north called Croissant where the terms of d'oil and Occitan interfere strongly (see Croissant). Instead, some territories are not generally considered to be part of Occitania according to the modern definition:[111]

- Several zones were dissocialized more or less precociously such as the Poitou, then the Charentes, the Gabay Country and the Petite Gavacherie (replacement by d'oil speakers after the Hundred Years' War), intermediate areas with the Franco-Provençal language in the Rhône-Alpes, the lower valleys of the Alps competed with the Piedmontese and Ligurian (Italy).

- The area "charnègue" ("métis" in Gascon) is influenced by the Basque Country because several Gascon communes were part of the former province essentially Basque Labourd and are now located in the west of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department: Bidache, Guiche, Came, Urt, Bassussarry, Montory, Mouguerre.[112] It is a region where both Basque and Occitan Gascon cultures coexist for a long time, just like the families of mixed marriages.[113]

- In several regions of the world we meet historical speakers of Occitan. These areas are not considered Occitan, with the exception of Guardia Piemontese which is a linguistic enclave in southern Italy.

- The zone of the royasc speech is generally excluded from Occitan despite the requests of its speakers who allowed to classify it as Occitan in Italy. This allows its speakers to benefit from the effects of the 482/1999 law on historical minorities, from which North-Italian dialects are excluded. In the past, and particularly shortly after the cession of Brigue and Tende to France, in 1947, was defended the more or less exclusive attribution of the royasc and the brigasc to the system of vivaro-alpine dialects,[114][115] while more recently, linguists specialized in the field recognize the prevalence of Ligurian phonetic, lexical and morphologic traits (Werner Forner,[116] Jean-Philippe Dalbera[117] and Giulia Petracco Sicardi[118] The Brigasc is a variant of the Royasc with addition of Occitan traits.[119]

History

[edit]This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (May 2012) |

Written texts in Occitan appeared in the 10th century: it was first used in legal texts, and then in literary, scientific, and religious texts. Spoken dialects of Occitan are many centuries older and appeared as soon as the 8th century, at least, as revealed through toponyms and Occitanized words left in Latin manuscripts.

Occitania was often politically united during the Early Middle Ages, under the Visigothic Kingdom and several Merovingian and Carolingian sovereigns. In the year 805 in Thionville, Charlemagne declared the partition of his empire into three autonomous territories along linguistic and cultural boundaries: what is now modern Occitania was to be formed from the reunion of a broader Provence and Aquitaine.[120] Instead, however, at the 9th century division of the Frankish Empire, Occitania was split into different counties, duchies and kingdoms, bishops and abbots. Since then, the country has never been politically united, although Occitania remained intact through a common culture. Nonetheless, Occitania suffered a tangle of varying loyalties to nominal sovereigns: from the 9th to the 13th centuries, the dukes of Aquitaine, the counts of Foix, the counts of Toulouse and the Counts of Barcelona competed for control over the various pays of Occitania.

Occitan literature flourished during this time period: in the 12th and 13th centuries, the troubadours invented courtly love (fin'amor), and the Lenga d'Òc spread throughout European cultivated circles; the terms Lenga d'Òc, Occitan, and Occitania first appeared at the end of the 13th century.

From the 13th to the 17th centuries, the kings of France gradually conquered Occitania. By the end of the 15th century, the nobility and bourgeoisie had started learning French, while the peasantry generally continued to speak Occitan; this process began from the 13th century in the two northernmost regions, northern Limousin and Bourbonnais. In 1539, Francis I issued the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts that imposed the use of French in administration. But despite measures such as this, a strong feeling of national identity against the French occupiers remained as Jean Racine wrote on a trip to Uzès in 1662: "We call here 'France' the entire country beyond the Loire, which is considered a foreign province."[121]

In 1789, the revolutionary committees tried to re-establish the autonomy of the "Midi" regions, using the Occitan language; however, Jacobin power prevented its realization.

The 19th century witnessed a strong revival of the Occitan literature, exemplified by the writer Frédéric Mistral, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1904. But from 1881 onwards, children who spoke Occitan at school were punished in accordance with minister Jules Ferry's recommendations; this led to a deprecation of the language known as la vergonha (the shaming). In 1914, fourteen million inhabitants in the region spoke Occitan,[122] but French overtook Occitan in prominence during the 20th century. The situation got worse with the media excluding the use of the langue d'oc. In spite of this decline, however, the Occitan language is still alive and gaining fresh impetus.

Image gallery

[edit]-

The Diocese of Vienne, 300 AC.

-

The Kingdom of Aquitaine, 806

-

Languedoc in 1209

-

Expulsion of the inhabitants from Carcassone in 1209

-

Protestant regions in modern France in the 16th century

Outer settlements

[edit]

Although not really a colony in a modern sense, there was an Occitan enclave in the County of Tripoli, founded in 1102 by Raymond IV of Toulouse during the Crusades north of Jerusalem. Most people in this county came from Occitania and Italy.

Around the 14th century, some "Provençal" settlements were founded by Valdenses in S southern Italy: the Capitanata?[clarification needed] area, Basilicata, and Calabria. Most of them were destroyed by the Inquisition during the 16th century, but the Guardia Piemontese[clarification needed] managed to keep its language and Occitan identity until now.

At the end of the 17th century, Valdenses fleeing persecution in the Occitan valleys settled in Baden, Hesse, and Wurtemberg (modern Germany). The use of the Occitan language vanished during the 20th century, but some Occitan placenames are still in use.

In the 19th century, Occitans settled in the Americas. Some Valdense colonies have retained their use of the language down to the present day, such as those in Uruguay and the United States.

Cultural and political movements

[edit]Occitanist associations or organizations

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2025) |

The oldest Occitanist association is the Felibritge[123], founded in 1854. In 1945, after the Second World War, some of the association's members founded a distinct movement, the Institut d'Estudis Occitans (Institute of Occitan Studies). Other organisations include the Calandreta, private associations of Occitan schools, and the Conselh de la Lenga Occitana (CLO), a scientific organization promoting codification of Occitan in the classical norm.

Anti-Occitanist Associations

[edit]Some associations adhering to Felibritge and Parlaren claim a Provençal language distinct from Occitan.

Other associations claim distinct "languages d'oc", even if, paradoxically, some of them are grouped together in an Alliance of Oc languages:

- Association advocating a distinct Auvergne identity: Cercle Terre d'Auvergne.

- Association advocating a distinct Béarnaise and Gascon language: Institut Béarnais et Gascon.

- Association advocating a distinct Cevenol language: Lou Clu en Ceveno.

- Associations advocating a distinct Provençal language: the Unioun Prouvençalo and its equivalent for Italy Unioun Prouvençalo Transaupino, the Collectif Prouvènço and its Italian equivalent Consulta provenzale.

Some associations have no affiliation with other oc countries:

- Association advocating a distinct Niçoise language: Acadèmia Nissarda.

- Associations advocating a distinct Provençal language: the Astrado Prouvençalo.

Pan-Occitanist associations

[edit]On the other hand, some groups claim an Occitan-Roman identity including the Catalan Countries (France-Spain).

- Groups actively participating in Eurocongress 2000: Occitan-Catalan Federation, Occitan-Catalan Fundation, Occitan-Catalan Circle of Twinning, Euroccat Association, Espaci Occitan Association.

- Other groups: Oc Valéncia Centre Internacional de Recerca i Documentació Científica.

Politics

[edit]Spain

[edit]In Spain, Aranese political parties alternately run the Conselh Generau d'Aran, the principal institution of government in the Val d'Aran. They also have elected officials in the municipalities of Aran, the Parliament of Catalonia and the Spanish Senate. They are close to Catalan parties with the exception of the localist party Partit Renovador d'Arties-Garòs who has, however, made alliances with Unity of Aran. Unity of Aran (UA-PNA) is a social-democratic and regionalist-autonomist party affiliated to Socialists' Party of Catalonia (PSOE-PSC), while Aranese Democratic Convergence (CDA-PNA), currently in power, is a centrist and autonomist party linked to the Democratic Convergence of Catalonia. Esquèrra Republicana Occitana (ÈRO) founded in 2008, Left/Social Democracy and Independence, is a local section of Republican Left of Catalonia. Corròp is a citizen movement born in February 2015 that aims to break with the Aranese bipartisanship and is inspired by the Catalan independence movement Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP), but with a view to Occitania.[124]

In the 2017 Catalan regional election, the electors of the Val d'Aran voted mostly for "constitutionalists," parties which support continued union with Spain.[125]

France

[edit]

In France, Occitan political parties and movements (such as the Occitan Nationalist Party, Occitan Party, Freedom !, ...) have had difficulty winning a large audience and getting officials elected. They had never had elected representatives in national or European institutions, or in general councils. However, in the 2010 French regional elections, the Occitan Party, within the framework of the participation of the federation Regions and Peoples with Solidarity to Europe Écologie, elected representatives to five regional councils: Dàvid Grosclaude in Aquitaine.,[126] Guilhem Latrubesse in Midi-Pyrénées, Gustau Aliròl in Auvergne, Anne-Marie Hautant and Hervé Guerrera in Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur.[127] The latter was also elected to the city council of Aix-en-Provence and counselor to the Agglomeration Community of Aix Country.[128] The movement Bastir! ran for the first time in the 2014 municipal elections and won 55 seats.[129][130] The president of the Occitan Party, Gustave Alirol, is currently also president of the "Regions and Peoples with Solidarity" party and vice-president of the "European Free Alliance," which participates in a group of 50 deputies in the European Parliament.[131]

- Gardarem la Tèrra: altermondialist.

- Iniciativa Per Occitània, political, cultural and social laboratory: independentist movement.

- Freedom ! esquèrra revolucionària occitana is a pan-Occitan far-left movement that replaced "Anaram on Patac", "Combat d'Òc" and "Hartèra" at the refounding convention of 19 September 2009.

- League for the restoration of Nicean freedoms: contests the annexation of the county of Nice to the French State in 1860.

- Nissa Rebela: Nicean autonomist party, close to the identity bloc.

- Linha Imaginòt: altermondialist.

- Languedocian Regionalist Movement: electoral coalition close to the PNO.

- Occitània Libertària: anarcho-communist.

- Our Country (País Nòstre): regionalist, established in Languedoc. Occitanie País Nòstre throughout Occitania since November 2019.

- Party of the Occitan Nation (PNO): moderate independence.

- Occitan Party (PÒC): autonomist, left/center-left. The PÒC adheres to larger entities:

- Since 2009, it has been inscribed in France in the Europe Écologie list as a participant in Regions and Peoples with Solidarity (RPS).

- European Free Alliance/Democratic Party of the Peoples of Europe (FTA/PDPE): The PÒC is a member of this European party.

- Greens–European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA group): Political group of the European Parliament.

- Unitat d'Òc: federates political activists from different horizons (PNO, PÒC and independent)

- Bastir!: social movement claiming attachment to Occitania (culture, history, environment ...)

| Political parties | Ideology |

|---|---|

| Occitan Party | Regionalism

Environmentalism |

| Party of the Occitan Nation | Occitan nationalism |

| Freedom ! | Occitan nationalism |

Italy

[edit]- Paratge: laboratory of political ideas. Its main section is in the Occitan Valleys (Italy). Its Provençal section is called Para(t)age Mar, Ròse e Monts.

- Movimento Autonomista Occitano (MAO): branch of the Party of the Occitan Nation in the Italian Occitan Piedmont. Only their newspaper Ousitanio Vivo continues to appear.

Monaco

[edit]There are currently no Occitan political movements in Monaco.

Former movements

[edit]Former political movements include:

- Anaram Au Patac: far left, participated in the CRÒC

- Occitan Comitat d'Estudis e d'Accion (COEA): Leftist autonomist. It was created in 1965.[132]

- Comitats d'Accion Occitana (CAO): Left.

- Corrent Revolucionari Occitan (CRÒC): separatist linked to the far left revolutionary.

- Entau País: leftist autonomist established in Gascony.

- Farem tot petar

- Communist Anarchist Federation of Occitan (FACO): independentist, libertarian communist.

- Hartèra, movement of the revolutionary youth of Occitania: extreme left.

- Lucha Occitana: group of intellectuals, students and agricultural unionists, ideologically left revolutionary, autonomist and socialist.

- Movement Socialista e Autonomista Occitan.

- Partit Provençau: autonomist.

- Pòble d'Òc: independentist and libertarian.

- The movement Volèm Viure al País (VVAP): socialist movement composed of different self-managing local groups. It no longer exists but the slogan that it has in fact taken up is often used. It was dissolved in 1987 to make room for the Occitan Party.[133]

Language

[edit]The Occitan language is only recognized as official, protected and promoted in the Val d'Aran (in Spain); in Italy it has the status of a protected language; and in France it only has acceptance in the educational network but without legal recognition.

The Fédération des langues régionales pour l'enseignement public calculated the number of students in the Occitan language in October 2005 at 4,326.[134]

According to a 2002 report by the French Ministry of Culture (Report to Parliament on the use of the French language, 2003), in public schools, collèges and lycées and private schools: in the academic year 2001–02, 67,549 students had enrolled in classes of or in Occitan.

Despite this precarious social position, Occitan was one of the official languages of the 2006 Turin Winter Olympics.

Culture

[edit]Literature

[edit]- The troubadour school first marked the emergence of a distinct Occitan culture during the High Middle Ages. The troubadours were highly appreciated for their refined lyricism and influenced many other similar "schools" throughout Europe. Troubadourism (the later shorthand) remained a tradition for centuries and its members were mainly from the aristocracy; the movement was epitomized by William IX, Duke of Aquitaine and Bertran de Born.

- Occitan literature experienced a rebirth during the Baroque period, mainly in Gascony through the Béarnese dialect. Indeed, Béarnese was the mother-tongue Henry IV of France, whose designation sparked a relative enthusiasm for Béarnese literature with the publication of works by Pey de Garros and Arnaud de Salette. Toulouse was also an important place for this renaissença, especially through the poems of Pèire Godolin. Nonetheless, Occitan literature following the death of Henry IV went into a significant period of decline, as witnessed by the fact that local poets, such as Clément Marot, began to write in French.

- Frédéric Mistral and his Félibrige school marked the renewal of the Occitan language in literature in the middle of the 19th century. Mistral won the 1904 Nobel Prize in Literature, illustrating the curiosity about the Provençal dialect (which was considered an exotic language) in France and in Europe at that time, with his Irish friend and colleague, the poet William Bonaparte-Wyse, choosing Provençal as his own language of composition.

- L'Acadèmia dels Jòcs Florals (The Academy of the Floral Games), held every year in Toulouse, is considered one of the oldest literary institution in the Western world (founded in 1323). Its main purpose is to promote Occitan poetry.

- In 1945 the cultural association L'Institut d'Estudis Occitans (The Institute of Occitan Studies) was created by a group of Occitan and French writers, including Jean Cassou, Tristan Tzara and Renat Nelli. Its purpose is to maintain and develop the language and influence of Occitania, mainly through the promotion of local literature and poetry.

Music

[edit]Romantic composer Gabriel Fauré was born in Pamiers, Ariège in the Pyrenees region of France. Déodat de Séverac, another Romantic music composer, was also born in the region, and, following his schooling in Paris, he returned to Occitania to compose; he sought to incorporate the music indigenous to the area into his compositions.

Cuisine

[edit]

Occitan cuisine is considered Mediterranean, but has some specific features that separate it from Catalan cuisine or Italian cuisine. Indeed, because of the size of Occitania and the great diversity of landscapes- from the mountaineering of the Pyrenees and the Alps, rivers and lakes, and finally the Mediterranean and Atlantic coast – it can be considered as a highly varied cuisine. Compared to other Mediterranean cuisines, Occitan gastronomy significantly uses basic elements and flavors, such as meat, fish and vegetables, along with the frequent usage of olive oil; elements from Atlantic coast cuisine are also common, such as cheeses, pastes, creams, butters and other high-calorie foods. Well-renowned meals common on the Mediterranean coast include ratatolha (the equivalent of Catalan samfaina), alhòli, bolhabaissa (similar to Italian Brodetto alla Vastese), pan golçat (bread with olive oil), and salads with mainly olives, rice, corn and wine. Another significant aspect that distinguishes Occitan cuisine from that of its Mediterranean neighbors is the abundant amount of aromatic herbs; some of them are typically Mediterranean, like parsley, rosemary, thyme, oregano or again basil.

Some world-renowned traditional meals are Provençal ratatolha (ratatouille), alhòli (aioli) and adauba (Provençal stew), Niçard salada nissarda (Salad Niçoise) and pan banhat (Pan-bagnat), Limousin clafotís (clafoutis), Auvergnat aligòt (aligot), Languedocien caçolet (cassoulet), or again Gascon fetge gras (foie gras).

Occitania is also home of a great variety of cheeses (like Roquefort, Bleu d'Auvergne, Cabécou, Cantal, Fourme d'Ambert, Laguiole, Pélardon, Saint-Nectaire, Salers), and a great diversity of wines (such as Bordeaux, Rhône wine, Gaillac wine, Saint-Émilion wine, Blanquette de Limoux, Muscat de Rivesaltes, Provence wine, Cahors wine, Jurançon). Alcohols such as Pastis and Marie Brizard or brandies such as Armagnac and Cognac are also produced in the area.

Gallery

[edit]-

Saint-Sernin's Basilica's chevet, Toulouse, which is the largest Romanesque church in Europe

-

Global view of the village of Conques.

-

View of the episcopal city of Albi

-

View of the Old Town of the city of Menton, on the French Riviera

-

View of Marseille, the largest city in Occitania

-

The Cistercian abbey of Sénanque

-

Gorges du Verdon Canyon

-

One of the many lakes of the Mercantour National Park, in the French Alps

-

The fortified town of Carcassonne, Aude

-

The Roman Pont du Gard

-

The headquarters of Michelin, Clermont-Ferrand

-

A surfer at Soorts-Hossegor, considered as one of the best surfing spots in the world.[135]

-

Cannes during the festival period

-

University of Montpellier's Faculty of Medicine, the oldest and still-active medical school in the world[136]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ English: /ˌɒksɪˈteɪniə/ OK-sih-TAY-nee-ə; Occitan: Occitània [utsiˈtanjɔ, uksiˈtanjɔ], locally [u(k)siˈtanjɔ], [ukʃiˈtanja] or [u(k)siˈtanja]; French: Occitanie [ɔksitani] ⓘ; Basque: Okzitania.

- ^ Singular feminine noun, first declension (a stem):

- Nominative, Occitaniă

- Vocative, Occitaniă

- Accusative, Occitaniam

- Genitive, Occitaniæ

- Dative, Occitaniæ

- Ablative, Occitaniā

References

[edit]- ^ "The ancient language of the South of France, was called, la langue d'oc, from the sound of its affirmative particle. From this circumstance, the country has been called Occitanie, and a specific portion of it, Languedoc. The French have lately formed a new adjective, Occitanique, to comprize all the dialects derived from the ancient tongue." in Sharon Turner, The history of England (during the middle ages), London, Longman, Hurst, &c. 1814. Read on GoogleBooks

- ^ Map of the Roman Empire, c. 400 AD

- ^ Map of the Visigothic Kingdom

- ^ Map of the 806 divisio regnorum'. Louis' share in yellow.

- ^ Fabrice BERNISSAN (2012). "Combien l'occitan compte de locuteurs en 2012 ?", Revue de Linguistique Romane, 76 (12/2011-07/2012), pp. 467-512

- ^ « De fait, le nombre des locuteurs de l’occitan a pu être estimé par l’INED dans un premier temps à 526 000 personnes, puis à 789 000, » ("In fact, the number of occitan speakers was estimated by the French Demographics Institute at 526,000 people, then 789,000") Philippe Martel, "Qui parle occitan ?" in Langues et cité Archived 16 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine n°10, December 2007.

- ^ "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous People". Archived from the original on 29 April 2009.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Juge (2001) Petit précis – Chronologie occitane – Histoire & civilisation, p. 14.

- ^ Joseph Anglade, Grammaire de l'ancien provençal ou ancienne langue d'oc, 1921, Part I, Chapter 1, p. 9: Le mot Langue d'Oc a d'abord désigné le pays où se parlait cette langue; c'était une expression géographique. Le pays de langue d'oc s'appelait en Latin Occitania (formé sans doute sur Aquitania) ("The words Langue d'Oc first designated the country where the language was spoken: it was a geographical expression. The land of the langue d'oc was called Occitania in Latin (probably coined from Aquitania").

- ^ Frederic Mistral, Lo Tresor dóu Felibrige (1878–1886), vol. II, p. 1171: "Les textes abondent qui montrent l'origine française ou ecclésiastique des expressions lingua occitana et Occitania. Le pape Innocent IV (1242–1254), un des premiers parle de Occitania dans ses lettres; les commissaires de Philippe le Bel qui rédigèrent l'arrêt sanè des coûtumes de Toulouse se déclarent Ad partes linguae occitanae pro reformatione patriae designati et stipulent que leur règlement est valable in tota lingua occitaniae."

- ^ Robèrt LAFONT (1986) "La nominacion indirècta dels païses", Revue des langues romanes nº2, tome XC, pp. 161–171.

- ^ Bodo MÜLLER. "Langue d'Oc, Languedoc, Occitan", in: Verba et Vocabula, Festschrift Ernst Gamillscheg, München 1968, pp. 323-342.

- ^ "Décret n° 2016-1264 du 28 septembre 2016 portant fixation du nom et du chef-lieu de la région Occitanie - Legifrance". www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^

Robert Lafont, Clefs pour l'Occitanie, Seghers, 1971; p. 11Occitanie means all the regions where we speak dialect of the Romance language called "langue d'oc". Occitania will therefore be defined on the map by the linguistic boundaries.

- ^

Occitania is everywhere where one has, in France, "the accent of the South", to the except for the department of Pyrénées-Orientales, which is Catalan, Corsica and the Basque Country. The Occitanophones are distributed in about thirty departments located south of a line that goes from the estuary of the Gironde to the Alps. It passes northern Libourne, eastern Angouleme, northern Confolens (Charente), Bellac (Haute-Vienne), northern Limoges, between Gueret and Aubusson (Creuse), between Vichy (Allier) and Riom (Puy-de-Dome). In the Saint-Etienne basin, Firminy is grazed on the south by the line that reaches the great Alps by cutting the Dauphiné in two. Grenoble is bordering on Occitania, which begins in La Mure. Finally, from La Mure to Besançon, and from Saint-Étienne to Friborg in Switzerland, there is an intermediate zone between Oc and Oïl; the Franco-Provençal area. Thus, Occitan is spoken in ten historical provinces: Guyenne, Gascony, County Foix, Béarn, Limousin, Auvergne, Languedoc, Provence, Dauphiné (south) and Nice. We must add the Val d'Aran, in the Spanish Pyrenees, and the Vaud valleys of Piedmont, in the Italian Alps.

— Jean-Pierre Richardot (1929-), Les Bacheliers de Montsêgur, "The World of Education," September 1976

- ^

Robert Lafont, "Clefs pour l'Occitanie", Seghers, 1971; p. 13It may be thought that 12th century, Occitania was still biting on Saintonge and Poitou. A process of northernization has allowed to read Occitan in transparency of the dialects of this region.

- ^ Occitan on the Basque television Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Jornalet 2 December 2014

- ^ Okzitanierak bizi duen egoeraz Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine EITB 23 November 2014

- ^ Las enclavas lingüisticas Archived 15 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, language = oc| Sumien Domergue| text = Sumien Domergue, Jornalet, 29 August 2016

- ^

Thus the great points of the ideal of medieval Occitan civilization were: "paratge" or feelings of equality, religious and racial tolerance, courtly love, Romanesque art and the emergence of class consciousness.

, Théorie de l’aliénation et émancipation ethnique. Suivi de: Pour en finir avec le Mammouth, Circle Alfons Mias, 2014, ISBN 1470961687— Joan-Pere Pujol

- ^ a b We can quote in particular the demographer Hervé Le Bras and the historian Emmanuel Todd who often use it in several of their works.

- ^ a b L'Origine des systèmes familiaux: Volume 1 Eurasia, Emmanuel Todd, publisher Gallimard, col. "NRF Essais", 2011 ISBN 9782070758425, 768 pages

- ^ La scripta administrativa en la Navarra medieval en lengua occitana: comentario lingüístico Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Ricardo Cierbide Martinena, in Zeitschrift für Romanische Philologie (ZrP). Volume 105, Issue 3-4, Pages 276-312, ISSN (online) 1865-9063, ISSN (print) 0049-8661, doi:10.1515/zrph.1989.105.3-4.276, November 2009

- ^ An Occitan scripta in the Kingdom of Navarre in the Middle Ages (13th–16th centuries) (formation and functioning) Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Louis Grange, 2012

- ^ Occitan medieval scripta in Euskal Herria (full text) Archived 21 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Ricardo Cierbide Martinena Fontes linguae vasconum: Studia et documenta, ISSN 0046-435X, Año n° 25, 62, 1993, pp. 43-60

- ^ "Le pouvoir royal et la lingua de hoc, alias Occitania" Archived 12 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine : "It is the irruption of the Capetian power far south of its original domain which causes the manufacture of the name of the countries which it integrates henceforth with this field. We can not call them "County of Toulouse", or "Viscount of Albi, Béziers, Carcassonne", since there are more viscounts since the late Montfort, nor counts after the death of Alphonse in 1271. However, we must find a clear designation, which is done at the end of 13th century. This will be the part of the royal domain where we speak a language that is not that of the other party, there in the north: the Langue d'oc, in latin Occitania. This can include, at random conquests, other areas where the same language is spoken ..."

- ^ a b Robert Lafont (1971, 1977, 1987), "Clefs pour l'Occitanie", Paris: Seghers, 1987: ISBN 2-232-11190-3.

- ^ a b "Histoire d'Occitanie" under the direction of André Armengaud and Robert Lafont. Paris: Hachette, 1979 ISBN 2-01-006039-3

- ^ a b Rober Lafont (2003). Petita istòria europèa d'Occitània, Canet: El Trabucaire ISBN 2-912966-73-6

- ^ Début des recherches sur les frontières linguistiques avec notamment Charles de Tourtoulon and Octavien Bringuier, Study on the geographical limit of the langue d'oc and langue d'oïl (with a map), 1876, Paris: Imprimerie nationale [reed. 2004, Masseret-Meuzac: Institute of Occitan Studies of Lemosin/Lo Chamin de Sent Jaume].

- ^ Books of Pierre Bec and Jules Ronjat in bibliography in the Occitan article and Gaston Tuaillon in the Francoprovençal.

- ^ a b c d Yvon Bourdet. Maria Clara Viguier Occitans sense o saber (Occitan without knowing it), Language and society, 1980, vol. 11, number 1, pp. 90-93. Maria Clara Viguier Occitans sense o saber (Occitans without knowing it) Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Universalis Encyclopedia – Occitan Language and Literature Archived 29 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine "Language of an Ethnicity Who Was Not A Nation, Its history is the constant quest for awareness that the most diverse imperatives have constantly challenged.

- ^ Jean Jaurès in: Jean Jaurès cahiers trimestriels, Issues 151-154, Society of Jaurésiennes Studies, publisher Society of Jaurésiennes Studies, 2000

- ^ Simone Weil and the Occitan homeland. Jews and Jewish Source in Occitania, Blanc Jòrdi, Vent Terral, Enèrgas, 1988, pp. 123-137.

- ^ Mistral and the Occitan people, Sylvain Toulze, Society of Occitan Publishers, 1931

- ^ "The Occitan people want to take the street for their rights – La Dépêche du Midi". Archived from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Occitan people – Douarnenez Film Festival". Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ PNO Manifesto, French version Archived 15 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Eurominority.eu, Association for the Promotion of Minorized European Peoples – Occitanie

- ^

Lou Felibrige es establi pèr garda longo-mai à la nacioun óucitano sa lengo, sis us, soun gàubi e tout ço que coustituïs soun eime naciounau. (The Felibrige is established to preserve the language, the traditions, the characters and all that constitutes the national spirit of the Occitan Nation.)

. 'Cartabeu de Santo-Estello' Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, n° 14, Avignon: 1924–1925.— Coll. Estatut dóu Felibritge (Bylaws of the Félibrige adopted in 1911)

- ^

All the characteristics of a nation, other than the language, are found in Occitania and we can see here also how much the language is the synthetic index of the nation. The Occitan originality is well marked compared to the neighboring ethnic groups, and this in all points of view: racial (racial compound where blood O is more frequent than in France, than in Italy or in Catalonia, less predominant in Euskadi), origin of the population (Ligures, Iberians and Gauls, strong Latin contingent, weak Visigoth input); ethnopsychological; political (Aquitaine uprisings under the Carolingians, National State of the Counts of Toulouse, union of all "the people of our language" against the French invasion, then constant peasant uprisings in all provinces, independent states during the wars of religion: Marseille, Montauban and especially Béarn, Cévennes' War, Girondins autonomism, finally since the 19th century, constant opposition vote giving majorities called "left" or ensuring the success of what appeared momentarily as the more protesting (Poujadism, Mitterrand), cultural (from the civilization of the troubadours, called by Engels a pre-Renaissance to Mistral and our contemporary literature), finally (and some will say above all) demographic, economic and social: underdevelopment and relative regression with neighboring ethnic groups (Italy, Catalonia, Euskadi and especially France), formerly known as escape of capital and now non-use or plunder of our resources by France, numerical predominance of the class of small-owners.

François Fontan (excerpts from: The Occitan Nation, Its Frontiers, Its Regions, 1969) Archived 9 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine.— The Occitan nation, its borders, its regions

- ^ See the Occitan Nation Party.

- ^ Text of law for the recognition of the Occitan national reality of Val d'Aran in Catalonia, Spain: Val d'Aran wants more autonomy

- ^ Occitans sens o saber ?; Maria Clara Viguièr; Vent Terral, 1979, Documents, Paperback 190 p -Sociological Essay-

- ^ There is also a variant of Occitan Monegasque aboriginal (district of the Port à la Condamine and Saint Roman) -called patois- which is called Moneguier. (René ANFOSSO, speaker of Moneguier p. 51 in REVEST Laurenç Nissa e Occitània per Garibaldi. Garibaldian anthology of Oc, publisher Serre, Nice, 212 p.).

- ^ "15% of the population of Monaco speaks Niçard variety of Provençal, which strongly French influences from the Monegasque territory. In fact, people speaking Niçard are mainly people over 50, but Provencal increases its status as a literary language (translated from: "A further 15% of the population of Monaco speaks the Niçard variety of Provençal, which greatly influences the French of the Monegasque region. In fact, the Niçard speaking community is comprisedof over 50 years of age, Provençal is increasingly gaining status as a literary language}} "Monaco: "Language Situation", in Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics (Second Edition)}}, 2006, p. 230 [1] Archived 12 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ On the basis of the French census of 1999, the population was estimated at 14 million inhabitants, see: ALCOUFFE Alan (2001) Cultura occitana e devolopament economic, 361-382 [13 December 2000], Treballs de la Societat catalana de geografia, vol. XVI, 2001, num. 52 Societat catalana de geografia 1 Archived 1 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine and Societat Catalana de Geografia 2 Archived 2 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "About 20% of the current population is born outside the territory (from 30 to 35% in Provence, less than 20% in the western territory). This immigration occurred mainly between 1975 and 1993. The languages spoken by the newcomers are mainly French and then the languages of immigration (Arabic, Berber, etc.). In The Euromosaic-Occitan study in France.

- ^ "About 20% of the population born in the territory left for work elsewhere, especially between 1963 and 1975. The most important causes are: the lack of employment opportunities, the industrial crisis and the mechanization of the work of the agricultural sector. European Commission> Languages> Euromosaic – Occitan in France

- ^ Philippe Martel admits: "let's say we do not know how many Occitanophones there are in this country" Martel Philippe, "Who speaks Occitan?","Languages and city", 10, Paris, DGLFLF, 12/2007.

- ^ Michel Zimmermann (1992), Southern societies around the year 1000, directory of sources and documents commented, Paris: CNRS editions, ISBN 2222047153

- ^ Robert Sabatier (1977), Histoire de la poésie française du XIXè –, Volume 2 (in French), Albin Michel, ISBN 2226222782

- ^ J. Stefanini, The meaning of the term "Occitanique" at Fabre d'Olivetds International Congress. of lang. and litt. of Southern France, Aix-en-Provence, 1961, p. 209

- ^ "It fires me in Narbonne, Aiguesmortess, Nymes & Besiers, colony & nille of great name, inhabited by IADIS soldiers the seventh legion of Rome, including the country man may seem auoir prins his name, then Easting Appointee Septimanie, and to present Ocitane & Languedo instead that the nõmoit Gotthicane, depending on whether we have dictated deuant." Two links of Paul Aemyle of the history of France, traduicts of Latin in French, by Simon de Monthiers, In Paris, From the printing press of Michel de Vascosan, leaving in the Rue S.Iaques, with the sign of the fountain. MD LVI (1556) p. 92. Read online Archived 28 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See also, later, "Arade, genti-homme de ceste Prouince Occitanie...", in Les récits historiques ou histoires divertissantes, entremeslées de plusieurs agreables rencontres & belles reparties. Par Iean-Pierre Camus, Evesque de Belley. In Paris, at Gervais Clousier, at the Palace, on the steps of the Saincte Chapelle. MDCXLIV en linha Archived 3 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Camus, Les récits historiques ou histoires divertissantes entremeslées de plusieurs agréables rencontres & belles réparties, Edicions Talvera, 2010 Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 979-1-09-069605-1.

- ^ Egli tutto pien d'ira Carlo attacò il fuoco, e spianò Narbona, Agate, Nemauso, e Biterra nobile Colonia de' Settumani, onde pare che hauesse tutta quella contrada il nome, che alhora si chiamava Settimania, & hora (come s'è gia detto) in uece di Gotticana, è chiamata Ocitania." Historia delle cose di Francia, raccolte fedelmente da Paolo Emilio da Verona, e recata hora a punto dalla Latina in questa nostra lingua Volgare, Venezia: Michele Tramezzino; 1549. online (images 144-145) Archived 31 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine and also. Archived 28 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Frantzösischer und anderer Nationen mit einlauffender Historien warhaffte Beschreibung: biß auff Henricum den Anderen ... in Neunthehen Bücher verfasset ... Sampt aller Königen Bildtnussen, Volum 2 Archived 28 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine p. 740.

- ^ Gilles Ménage, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue française, 1750.

- ^ "This province was long known as "Gallia Narbonensis", then Septimania. When the Roman Empire was divided again, the name of Occitania was given to the regions westward (of Provence), and of Novempopulania to the province of Bordeaux."

- ^ "RIGAUDIÈRE, Albert. Chapitre III. La royauté, le Parlement et le droit écrit aux alentours des années 1300 In : Penser et construire l’État dans la France du Moyen Âge (XIIIe-XVe siècle), 2003. "

- ^ Revista tolsana Infòc, number 265, Genièr 2008.

- ^ Pierre Bec, op. cit., p. 20.

- ^ "Old map of Occitania" (GIF). Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Trobadors, Martial Peyrouny, CRDP of Aquitaine, 2009, p. 14. ISBN 9 782866 175399

- ^ Louis-Étienne Arcère, Histoire de la Ville de la Rochelle et du Pays d'Aulnis, 1756, p. 40 online.

- ^ Pierre Bec, op. cit., p. 65.

- ^ "Roumanio • Tresor dóu Felibrige - Dictionnaire provençal-français". Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ The United Provinces of the South Archived 12 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine, note published on the Musée virtuel du protestantisme

- ^ Dom Vaissette.

- ^ Alain Viaut quotes the Languedocian dictionary of the Abbé de Sauvages (1785): Hence it follows that not only the Provençal, but all Gascon idioms of the southern provinces are within the purview of our dictionary. Alain Viaut, "Practices and representations of Occitan in Aquitaine", in Variable territoriale et promotion des langues minoritaires, MSHA, 2007, p. 146 online.

- ^ "OCCITANIA (Geog. Anc.) Is the name that some authors of the Middle Ages gave to the province of Languedoc but this name was common to all the people who said yes, that is to say, to the inhabitants of Gascony, Provence, Dauphine, and Languedoc, whose modern name was formed".

- ^ Explanation Online.

- ^ a b Óucitanìo. Aix-en-Provence: Remondet-Aubin: Lou Tresor dóu Felibrige, Provençal-French Dictionary. 1979. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017 – via Mistralian norm, for Occitània in classical norm) in: Frédéric Mistral (1879 - 1886).

See also the statutes of Felibritge adopted in 1911, article 11: Tóuti li Felibre majourau o manteneire soun coumparti dins de seicioun terrenalo dicho mantenènço e courrespoundènto, tant que se pòu, is anciano prouvinço de l'Óucitanìo o i grand dialèite de La Lengo d'O "All major felibritgists or maintainers are divided into territorial sections known as maintenances and corresponding, as far as possible, to the former provinces of Occitania or the great dialects of the Occitan language.

- ^ Pierre Pasquini, Le pays des parlers perdus, preface by Robert Lafont, Montpellier, Presses du Languedoc, 1994, see page 160 for more clarification.

- ^ Frédéric Mistral, Oucitanìo article, The Treasure of the Felibritge, 1878.

- ^ Robèrt Lafont (1986) Indirect nominacion dels païses, Revue des langues romaines number 2, volume XC, pp. 161-171.

- ^ André Dupuy, Marcel Carrieres and André Nouvel, Histoire de l'Occitanie, Publisher Connaissance de l'Occitanie, Montpellier, 1976 p. 58.

- ^ Robert Lafont, "The Classical Age", Volume I of the "History and Anthology of the Occitan literature", Montpellier, Presses du Languedoc, 1997.

- ^ See The Invention of Europe of Emmanuel Todd.

- ^ see chapters 2, 3 and 5 of this book Archived 5 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Jean-François Gerkens, Ibid, pp. 74-75.

- ^ Private Law Compared By Jean-François Gerkens .

- ^ Goubert and Roche Archived 9 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Démographie : en trente ans, comme vous avez changé !". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "The level of education in Europe in 2010". Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "INSEE-Part des familles nombreuses". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ is the red midi really a reality? Interview with Jean-Jacques Becker and Gilles Candar[permanent dead link], published in the journal Arkheia number 17-18.

- ^ Emmanuel Todd (1951-), Qui est Charlie? Sociologie d'une crise religieuse, Baume-Les-Dames, Éditions du Seuil, 2015, ISBN 978-2-02-127909-2, p. 176, map p. 177

- ^ Andre Armengaud and Robert Lafont (dir.), "Histoire d'Occitanie", Paris, Hachette, 1979, 949 pages.

- ^

in Jean-Pierre Camus, Les Récits historiques ou histoires divertissantes, entremeslées de plusieurs agreables rencontres & belles reparties Archived 3 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 1644.Arade, genti-homme de ceste Prouince Occitanie

- ^

in Jean Besly, History of the Counts of Poitou and the dukes of Guyenne since 811 to Louis the Younger Archived 31 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 1647.Raimond I count of Tholose or if Occitanie

- ^ Orders of the Kings of France of the third race... Third volume, Containing the ordinances of King John from the beginning of the year 1355 until his death arrived April 8, 1364 / by M. Secousse, Imprimerie Royale, Paris, 1732, on line on Gallica Archived 31 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Mullié, Charles (1852). . (in French). Paris: Poignavant et Compagnie.

General Frégeville had to fight the occult orders of the duke Angouleme and his chief of staff, the Duke of Damascus. The Prince's plan was to disorganize the army; he succeeded, and General Frégeville was retired. It is known that the Duke of Angouleme was suspected at that time of wanting to form an independent kingdom under the name of the Kingdom of Occitania.

- ^ "Faced with these excesses, fear outweighs explicit convictions -as evidenced by the isolation of Voyer d'Argenson when he denounces them in the House- and the central government is struggling to react: the prefects appointed by the government only arrive in his departments at the end of July, and suffer from the competition of the commissioners who have been appointed by the Duke of Angouleme. The latter is also recalled to Paris by Louis XVIII, who cancels all the nominations to which his nephew had proceeded and published, on 1 September, a "proclamation on the excesses of the South". Written by Pasquier, this text condemns the "odious enterprise" described as "an attack against us and against France". The royal intervention puts an end to the troubles -except in Nîmes, where they continue until November- strongly reminding that no one can substitute for the authority of the king. But it aroused the anger of the leaders of exalted southern royalism (the Marquis of Villeneuve, the Abbé de Chièze, the Baron of Calvière) who, having failed to establish a Viceroyalty of Occitania, had hoped to take advantage circumstances to restore the institutions of the Ancien Régime to the benefit of the local nobility. Bertand GOUJON. Post-Revolutionary Monarchies. 1814-1848. Paris: The Threshold. 2012. ISBN 978-2-02-109445-9. Read on Google Books

- ^ History of England During the Middle Ages, 1814.

- ^ "The Felibritge is established to preserve the language, the customs, the genius of the Occitan nation. Its doctrine is contained in the works of Frédéric Mistral and his disciples") Article 2 of the statutes in the Cartabèu de Santo Estello online at CIEL d'Oc[permanent dead link]

- ^ Simon Calamel and Dominique Javel, The Langue d'oc for standard, p. 203: "IEO ... competitive organization but not necessarily enemy... created in 1945".

- ^ Law n°94-665 of August 4, 1994 relative to the use of the French language Archived 27 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine "Any inscription or announcement affixed or made on the public road, in a place open to the public or in a means of public transport and intended for the information of the public must be formulated in French."

- ^ "What is the Occitanie region?". Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Survey for the new name of the large region regrouping "Midi-Pyrénées" and "Languedoc-Roussillon" [2] Archived 2 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Sasor, Rozalia (1 December 2020). "The historical background of Catalan separatism: The case of Occitania" (PDF). Review of Nationalities. 10 (1): 153–167. doi:10.2478/pn-2020-0011. ISSN 2543-9391. S2CID 235076124. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ Débax, Hélène (2003). "L'échec de l'Etat occitan. Sur les divergences de l'évolution entre Occitanie et Catalogne (IXe-XIIIe siècles)". Càtars i trobadors: Occitània i Catalunya, renaixença i futur. Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya. pp. 68–75. ISBN 9788439361497. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ Costen, M. D. (1997). The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade. Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 0-7190-4331-X. OCLC 36407762.

- ^ Fernández-Cuadrench, Jordi (2014). "L'Estat que no va ser: catalans i occitans entre els segles VIII i XIII. A propòsit del vuitè centenari de la Batalla de Muret". Butlletí de la Societat Catalana d'Estudis Històrics (in Catalan) (25): 47–85. doi:10.2436/20.1001.01.126. ISSN 2013-3995.

- ^ Lamuela, Xavier. "Catalan and Occitan: one diasystem, two languages". www.trob-eu.net. TrobEu, Trobadours and European Identity. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ Fabra, Pompeu (1934). "Desviacions en els conceptes de llengua i de pàtria". Obres Completes de Pompeu Fabra en format digital (PDF) (in Catalan). Vol. 9, Textos i materials. Institut d'Estudis Catalans–Universitat Pompeu Fabra. pp. 679–682. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Catalan language". www.britannica.com. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

Catalan is most closely related to the Occitan language of southern France and to Spanish, but it is clearly distinct from both.

- ^ "Catalonia recognizes Aran's national identity". Nationalia. CIEMEN. 21 January 2015. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ Notably Carles de Tortolon, & Octavien Bringuier, Étude sur la limite géographique de la langue d’oc et de la langue d’oïl (avec une carte), 1876, Paris: Imprimerie Nationale [reed. 2004, Masseret-Meuzac: Institute of Occitan Estudis of Lemosin/Lo Chamin of Sent Jaume].

- ^ See for example the map in Occitània i l'occità Archived 13 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, a popular work on Occitania and Occitan published by the Autonomous Government of Catalonia (in Catalan).

- ^ Guiche, Came, Urt, Bidache, Bassussarry, Montory, Mouguerre... are they really Gascon?.

- ^ Sharnègos Archived 24 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "In fact, the community of Brigue has its most distant origins in the emigrations of the 12th century after the conquest of Languedoc and Provence by the "barons of the North", conquest followed by religious persecutions (note 10). Thus, their language is a Provençal speech with an old Ligurian substratum in which words from French were mixed.

(Note 10) Traces of Provençal civilization can be found in some Alpine valleys of Piedmont [...] In Liguria we can find smaller traces in Lower Roya (Olivetta San Michele, Airole, Libri) and in the Alps. Rochetta Nervina, Pigna and Triora. Guido Lucarno, "The peace treaty of 1947 between Italy and France. Consequences on the Border and on the Development of the Roya Valley", p. 121 in André-Louis Sanguin, Mare Nostrum : dynamiques et mutations géopolitiques de la Méditerranée, Paris : L'Harmattan, 2000. - ^ Werner Forner, "Smoke and fire. About attempts to delimit the Occitan south-east area. First part: From 1850 to 1950", in P. Fabre (ed.), Mixes dedicated to the memory of Prof. Paul Roux, La Farlède (Var Association for the Teaching of Provençal), 1995, pp. 155–180.

- ^ Werner Forner, "About the ligurian intemelian. The coast, the hinterland", in Works of the Linguistic Circle of Nice, 7-8 (1985–1986), Werner Forner, Areallinguistik I: Ligurian, in Lexikon der Romanistischen Linguistik (LRL), IV, Tübingen 1988, pp. 453-469.; Werner Forner, «Linguistic Geography and Reconstruction, in the example of the Ligurian Intemelian», in Proceedings of the I International Symposium on Ancient Provençal, Ancient French and the Ancient Ligurian, Nice, September 1986 ("Bulletin of the Center for Romanticism and Late Latinity"), Nice 1989, pp. 125-140., Werner Forner, «Fra Costa Azurra e Riviera: be li ngue in contatto", in V. Orioles, Fiorenzo Toso (ed.), Circolazioni linguistiche e culturali nello spazio mediterraneo. Miscellanea di studi, Recco 2008, pp. 65-90.

- ^ Jean-Philippe Dalbera, Les parlers des Alpes-Maritimes. Étude comparative. Essai de reconstruction.. London 1994, publication of the International Association of Occitan Studies.

- ^ Giulia Petracco Sicardi, E. Azaretti, "Studi linguistici sull'anfizona Liguria-Provenza", In Dizionario Etimologico Storico Ligure, Alessandria 1989, at pp. 11-62., di Giulia Petracco Sicardi,"Contribute alla definizione dell'anfizona Liguria-Provenza".

- ^ "The Brigasc has an Occitan component that denies the belief of some people that this speech would be part of the Ligurian dialects." The feeling of belonging to the Occitan culture is sufficiently shared by the locals "on the A Vaštéra site[permanent dead link].

- ^ Jean-Pierre JUGE (2001) Petit précis – Chronologie occitane – Histoire & civilisation, p. 19.

- ^ Frederic Mistral, Lou Tresor dóu Felibrige ou Dictionnaire provençal-français embrassant les divers dialectes de la langue d'oc moderne (1878–1886), vol. I, p. 1182: "Le poète Racine écrivait d'Uzès en 1662: «Nous appelons ici «la France» tout le pays qui est au-delà de la Loire. Celui-ci passe comme une province étrangère.»"

- ^ Joseph Anglade, Grammaire de l'ancien provençal ou ancienne langue d'oc, 1921: La Langue d'Oc est parlée actuellement par douze ou quatorze millions de Français ("Occitan is now spoken by twelve or fourteen million French citizens").