Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

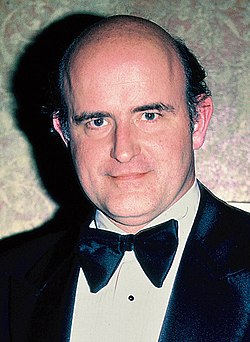

Peter Boyle

View on Wikipedia

Peter Richard Boyle (October 18, 1935 – December 12, 2006) was an American actor. He is known for his work as a character actor on film and television and received several awards including a Primetime Emmy Award and a Screen Actors Guild Award.

Key Information

He is best known for his role as the patriarch Frank Barone on the CBS sitcom Everybody Loves Raymond from 1996 to 2005. For his role he received seven nominations for the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series. For his role as Clyde Bruckman in the Fox science-fiction drama The X-Files in 1996 he won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Drama Series.

On film, he starred as the comical monster in Mel Brooks's film spoof Young Frankenstein (1974). He won praise in both comedic and dramatic parts in Joe (1970), The Candidate (1972), The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), Taxi Driver (1976), F.I.S.T. (1978) and Where the Buffalo Roam (1980). He later took supporting roles in Honeymoon in Vegas (1992), The Shadow (1994), That Darn Cat (1997), and The Adventures of Pluto Nash (2002).[1]

Early life and education

[edit]Peter Richard Boyle was born in Norristown, Pennsylvania, the son of Alice (née Lewis) and Francis Xavier Boyle.[2] He was the youngest of three children and had two elder sisters.[3][4] He moved with his family to nearby Philadelphia.[5]

His father, Francis, was a Philadelphia TV personality from 1951 to 1963. Among many other roles, he played the Western show host Chuck Wagon Pete, as well as hosting the after-school children's program Uncle Pete Presents the Little Rascals, which showed vintage Little Rascals and Three Stooges comedy shorts alongside Popeye cartoons. He also appeared at times on Ernie Kovacs' morning program on WPTZ (now KYW-TV).[6]

Boyle's paternal grandparents were Irish immigrants, and his mother was of mostly French, English, Scottish and Irish descent.[7][8] He was raised Catholic and attended St. Francis de Sales School and West Philadelphia Catholic High School for Boys. After graduating from high school in 1953, Boyle spent three years in formation with the De La Salle Brothers, a Catholic teaching order. He lived in a house of studies with other novices earning a Bachelor of Arts degree from La Salle University in Philadelphia in 1957, but left the order because he did not feel called to religious life.[9]

While in Philadelphia, he worked as a cameraman on the cooking show Television Kitchen hosted by Florence Hanford.[10]

After graduating from Officer Candidate School in 1959, he was commissioned as an ensign in the United States Navy, but his military career was shortened by a nervous breakdown.[7] In New York City, Boyle studied with acting coach Uta Hagen at HB Studio[11] while working as a postal clerk and a maitre d'.[12]

Career

[edit]1966–1971: Early roles and breakthrough

[edit]

In 1963, Boyle was hired for the Wayside Theatre's opening season. One of his starring roles that year was in Summer and Smoke by Tennessee Williams.[13][14] Boyle played Murray the cop in a touring company of Neil Simon's The Odd Couple,[1] leaving the tour in Chicago and joining The Second City ensemble there.[12] He had a brief scene as the manager of an indoor shooting range in the critically acclaimed 1969 film Medium Cool, filmed in Chicago.[citation needed]

Boyle gained acclaim for his first starring role as the title character, a bigoted New York City factory worker, in the 1970 movie Joe. The film's release was surrounded by controversy over its violence and language. During this time, Boyle became close friends with actress Jane Fonda, and he participated with her in many protests against the Vietnam War. After seeing people cheer at his role in Joe, Boyle refused the lead role in The French Connection (1971),[1] as well as other film and television roles that he believed glamorized violence. However, in 1974, he starred in a film based on the life of murdered New York gangster "Crazy" Joey Gallo, called Crazy Joe.[citation needed]

1972–1995: Character actor roles

[edit]His next major role was as the campaign manager for a U.S. Senate candidate (Robert Redford) in The Candidate (1972). In 1973, he appeared in Steelyard Blues with Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland, a film about a bunch of misfits trying to get a Catalina flying boat in a scrapyard flying again so they could fly away to somewhere with not so many rules. He also played an Irish mobster opposite Robert Mitchum in The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973). Boyle had another hit role as Frankenstein's monster in the 1974 Mel Brooks comedy Young Frankenstein, in which, in an homage to King Kong, the monster is placed onstage in top hat and tails, grunt-singing and dancing to "Puttin' on the Ritz". Boyle said at the time, "The Frankenstein monster I play is a baby. He's big and ugly and scary, but he's just been born, remember, and it's been traumatic, and to him the whole world is a brand-new, alien environment. That's how I'm playing it".[12] Boyle met his wife, Loraine Alterman, on the set of Young Frankenstein while she was there as a reporter for Rolling Stone.[15] He was still in his Frankenstein makeup when he asked her for a date.[16] Through Alterman and her friend Yoko Ono, Boyle became friends with John Lennon, who was the best man at Boyle and Alterman's 1977 wedding.[17] Boyle and his wife had two daughters, Lucy and Amy.[citation needed]

Boyle received his first Emmy nomination for his acclaimed dramatic performance in the 1977 television film Tail Gunner Joe, in which he played Senator Joseph McCarthy. He was more often cast as a character actor than as a leading man. His roles include the philosophical cab driver Wizard in Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976), starring Robert De Niro; a bar owner and fence in The Brink's Job (1978); the private detective hired in Hardcore (1979); the attorney of gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson (played by Bill Murray) in Where the Buffalo Roam (1980); a corrupt space mining-facility boss in the science-fiction film Outland (1981), opposite Sean Connery; Boatswain Moon in the (1983) pirate comedy Yellowbeard, also starring Cheech and Chong, Madeline Kahn, and members of the comedy troupe Monty Python.[citation needed]

In 1984, he played a local crime boss named Jocko Dundee on his way to retirement, starring Michael Keaton in the comedy film Johnny Dangerously, a psychiatric patient who belts out a Ray Charles song in the comedy The Dream Team (1989), also starring Michael Keaton; a boss of an unscrupulous corporation in the sci-fi movie Solar Crisis (1990) with Charlton Heston and Jack Palance; the title character's cab driver in The Shadow (1994), starring Alec Baldwin; the father of Sandra Bullock's fiancée in While You Were Sleeping (1995); the corporate raider out to buy Eddie Murphy's medical partnership in Dr. Dolittle (1998); the hateful father of Billy Bob Thornton's prison-guard character in Monster's Ball (2001); Muta in The Cat Returns (2002); and Old Man Wickles in the comedy Scooby Doo 2: Monsters Unleashed (2004). In cameo roles, he can be seen as a police captain in Malcolm X (1992), and as a drawbridge operator in Porky's Revenge (1985). In 1992, he starred in Alex Cox's Death and the Compass, an adaptation of Jorge Luis Borges' La Muerte y la Brujula. However, the film was not released until 1996.[citation needed]

His New York theater work included playing a comedian who is the object of The Roast, a 1980 Broadway play directed by Carl Reiner. Also in 1980, he co-starred with Tommy Lee Jones in an off-Broadway production of playwright Sam Shepard's acclaimed True West. Two years later, Boyle played the head of a dysfunctional family in Joe Pintauro's less well-received Snow Orchid, at the Circle Repertory.[citation needed]

In 1986, Boyle played the title role of the television series Joe Bash, created by Danny Arnold. The comedy drama followed the life of a lonely, world-weary, and sometimes compromised New York City beat cop, whose closest friend was a prostitute, played by actress DeLane Matthews.[18]

In October 1990, Boyle suffered a near-fatal stroke that rendered him completely speechless and immobile for nearly six months. After recovering, he went on to win an Emmy Award in 1996 as Outstanding Guest Actor in a Drama Series for his appearance on The X-Files. In the episode, "Clyde Bruckman's Final Repose", he played an insurance salesman who could see selected things in the near future, particularly others' deaths. Bruckman was named after a real person, also named Clyde Bruckman, who was a comedy director and writer who had worked with Buster Keaton, Laurel and Hardy and The Three Stooges among others. Boyle also guest-starred in two episodes as Bill Church Sr. in Lois and Clark: The New Adventures of Superman. He appears in Sony Music's unaired Roger Waters music video "Three Wishes" (1992) as a scruffy genie in a dirty coat and red scarf, who tries to tempt Waters at a desert diner.[19][20]

1996–2005: Everybody Loves Raymond

[edit]

Boyle played Frank Barone in the CBS sitcom Everybody Loves Raymond, which aired from 1996 to 2005. He was nominated for an Emmy seven times for this role and never won, though fellow co-stars Brad Garrett, Ray Romano, Patricia Heaton, and Doris Roberts won at least one Emmy each for their performances.[citation needed]

In 1999, he had a heart attack[15] on the set of Everybody Loves Raymond. He soon regained his health and returned to the series. After the incident, Boyle was drawn back to his Catholic faith and resumed attending Mass.[21]

In 2001, he appeared in the film Monster's Ball as the bigoted father of Billy Bob Thornton's character. Introduced by comedian Carlos Mencia as "the most honest man in show business", Boyle made guest appearances on three episodes of the Comedy Central program Mind of Mencia, one of which was shown as a tribute in a segment made before Boyle's death, in which he read hate mail, explained the "hidden meanings" behind bumper stickers, and occasionally told Mencia how he felt about him.[citation needed]

Starting in late 2005, Boyle and former television wife Doris Roberts appeared in television commercials for the 75th anniversary of Alka-Seltzer, reprising the famous line, "I can't believe I ate that whole thing!" Although this quote has entered into popular culture, it is often misquoted as, "...the whole thing."[22] Boyle was in all three of The Santa Clause films. In the original, he plays Scott Calvin's boss Mr. Whittle. In the sequels, he plays Father Time.[citation needed]

Death and reactions

[edit]On December 12, 2006, Boyle died at the age of 71 at New York Presbyterian Hospital in New York City after suffering from multiple myeloma and heart disease.[23][24] At the time of his death, he had completed his roles in the films All Roads Lead Home and The Santa Clause 3: The Escape Clause—the latter being released one month before his death—and was scheduled to appear in The Golden Boys.[25] The end credits of All Roads Lead Home include a dedication to his memory.[citation needed]

Boyle's death had a tremendous effect on his former co-stars from Everybody Loves Raymond, which had ceased production less than two years before his death. When asked to comment on Boyle's death, his cast members heaped praise on Boyle. Ray Romano was personally affected by the loss, saying, "He gave me great advice, he always made me laugh, and the way he connected with everyone around him amazed me." Patricia Heaton stated, "Peter was an incredible man who made all of us who had the privilege of working with him aspire to be better actors."[26]

On October 18, 2007 (which would have been Boyle's 72nd birthday), his friend Bruce Springsteen dedicated "Meeting Across the River" to Boyle during a Madison Square Garden concert with the E Street Band in New York. Springsteen segued into "Jungleland" in memory of Boyle, stating: "An old friend died a while back – we met him when we first came to New York City... Today would have been his birthday."[27]

After Boyle died, his widow Loraine Alterman Boyle established the Peter Boyle Memorial Fund in support of the International Myeloma Foundation (IMF).[28] Boyle's closest friends, family, and co-stars have since gathered yearly for a comedy celebration fundraiser in Los Angeles. Acting as a tribute to Boyle, the annual event is hosted by Ray Romano and has included performances by many comedic veterans including Dana Carvey, Fred Willard, Martin Mull, Richard Lewis, Kevin James, Jeff Garlin, and Martin Short. Performances typically revolve around Boyle's life, recalling favorite moments with the actor. The comedy celebration has been noted as the most successful fundraiser in IMF history. The first event held in 2007 raised over $550,000, while the following year over $600,000 was raised for the Peter Boyle Memorial Fund in support of the IMF's research programs.[29]

He was interred at Green River Cemetery in Springs, New York.[citation needed]

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | The Group[citation needed] | Unknown role | Uncredited |

| 1968 | The Virgin President | General Heath | |

| 1969 | Medium Cool | Gun Clinic Manager | |

| The Monitors | Production Manager | ||

| 1970 | Joe | Joe Curran | |

| Diary of a Mad Housewife | Man in Group Therapy Session | Uncredited | |

| 1971 | T.R. Baskin | Jack Mitchell | |

| 1972 | The Candidate | Marvin Lucas | |

| F.T.A. | Himself | Documentary | |

| 1973 | Steelyard Blues | Eagle Thornberry | |

| Slither | Barry Fenaka | ||

| Kid Blue | Preacher Bob | ||

| The Friends of Eddie Coyle | Dillon | ||

| 1974 | Crazy Joe | Joe Gallo | |

| Young Frankenstein | The Monster | ||

| Ghost in the Noonday Sun | Ras Mohammed | ||

| 1976 | Taxi Driver | Wizard | |

| Swashbuckler | Lord Durant | ||

| 1978 | F.I.S.T. | Max Graham | |

| The Brink's Job | Joe McGinnis | ||

| 1979 | Hardcore | Andy Mast | |

| Beyond the Poseidon Adventure | Frank Mazzetti | ||

| 1980 | Where the Buffalo Roam | Carl Lazlo | |

| In God We Trust (or Gimme That Prime Time Religion) | Dr. Sebastian Melmoth | ||

| 1981 | Outland | Mark B. Sheppard | |

| 1982 | Hammett | Jimmy Ryan | |

| 1983 | Yellowbeard | Moon | |

| 1984 | Johnny Dangerously | Jocko Dundee | |

| 1985 | Turk 182 | Detective Ryan | |

| 1987 | Surrender | Jay | |

| Walker | Cornelius Vanderbilt | ||

| 1988 | The in Crowd | "Uncle Pete" Boyle | |

| Red Heat | Lou Donnelly | ||

| Funny | Himself | Documentary | |

| 1989 | The Dream Team | Jack McDermott | |

| Speed Zone | Police Chief Spiro T. Edsel | ||

| 1990 | Solar Crisis | Arnold Teague | |

| Men of Respect | Matt Duffy | ||

| 1991 | Kickboxer 2: The Road Back | Justin Maciah | |

| 1992 | Nervous Ticks | Ron Rudman | |

| Honeymoon in Vegas | Chief Orman | ||

| Malcolm X | Captain Green | ||

| 1994 | Bulletproof Heart | George | |

| The Shadow | Moe Shrevnitz | ||

| The Santa Clause | Mr. Whittle | ||

| The Surgeon | Lieutenant McEllwaine | ||

| 1995 | Born to Be Wild | Gus Charnley | |

| While You Were Sleeping | Ox Callaghan | ||

| 1996 | Sweet Evil | Jay Glass | |

| Milk & Money | Belted Galloway | ||

| 1997 | That Darn Cat | Pa | |

| 1998 | Species II | Dr. Herman Cromwell | Uncredited |

| Dr. Dolittle | Calloway | ||

| 2001 | Monster's Ball | Buck Grotowski | |

| Lunch Break | Lou | Short | |

| 2002 | The Cat Returns | Muta (voice role) | English version |

| The Adventures of Pluto Nash | Rowland | ||

| The Santa Clause 2 | Father Time | Uncredited | |

| 2003 | True Confessions of the Legendary Figures | Father Time | Short |

| Bitter Jester | Himself | Documentary | |

| 2004 | Scooby-Doo 2: Monsters Unleashed | Old Man Wickles | |

| 2006 | The Santa Clause 3: The Escape Clause | Father Time | |

| 2007 | The Shallow End of the Ocean | Larry Aims (voice role) | Short, posthumous release |

| 2008 | All Roads Lead Home | Poovey | Posthumous release |

Television

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | The Man Who Could Talk to Kids | Charlie Datweiler | TV movie |

| 1976, 1999 | Saturday Night Live | Himself / host / guest | 2 episodes |

| 1977 | Tail Gunner Joe | Joe McCarthy | TV movie |

| 1979 | From Here to Eternity | Fatso Judson | Miniseries |

| 1986 | Joe Bash | Joe Bash | 6 episodes |

| 1987 | Conspiracy: The Trial of the Chicago 8 | David Dellinger | TV movie |

| Echoes in the Darkness | Sergeant Joe Van Nort | Miniseries | |

| 1988 | Superman 50th Anniversary | James "Jimmy" Malone | TV movie |

| Cagney & Lacey | Phillip Greenlow | Episode: "A Class Act" | |

| Disaster at Silo 7 | General Sanger | TV movie | |

| 1989 | Guts and Glory: The Rise and Fall of Oliver North | Admiral John Poindexter | |

| 1989–1991 | Midnight Caller | J.J. Killian | 3 episodes |

| 1990 | American Playwrights Theater: The One-Acts | Jake | Episode: "27 Wagons Full of Cotton" |

| Challenger | Roger Boisjoly | TV movie | |

| Poochinski | Stanley Poochinski (voice role) | TV Short | |

| The Tragedy of Flight 103: The Inside Story | Fred Ford | TV movie | |

| 1992 | In the Line of Duty: Street War | Detective Dan Reilly | |

| Cuentos de Borges | Erik Lonnrot | Episode: "Death and the Compass" | |

| 1992–1993 | Flying Blind | Alicia's Dad | 2 episodes |

| 1993 | Tribeca | Harry | Episode: "The Hopeless Romantic" |

| Taking the Heat | Judge | TV movie | |

| 1994 | Royce | Huggins | |

| Philly Heat | Stanislas Kelly | TV pilot | |

| 1994–1995 | NYPD Blue | Dan Breen | 5 episodes |

| Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman | Bill Church | 2 episodes | |

| 1995 | The X-Files | Clyde Bruckman | Episode: "Clyde Bruckman's Final Repose" |

| 1996 | In the Lake of the Woods | Tony Carbo | TV movie |

| 1996–1997 | The Single Guy | Walter Eliot | 2 episodes |

| 1996–2005 | Everybody Loves Raymond | Frank Barone | 210 episodes |

| 1997 | A Deadly Vision | Detective Salvatore DaVinci | TV movie |

| Cosby | Frank Barone | Episode: "Lucas Raymondicus" | |

| 1998 | The King of Queens | Episode: "Road Rage" | |

| 1999 | Hollywood Squares | Himself / Panelist | 5 episodes |

| 2000 | Behind the Music | Himself | Episode: "John Lennon: The Last Years" |

| 2002 | Master Spy: The Robert Hanssen Story | Howard Hanssen | TV movie |

| 2005–2006 | Mind of Mencia | Himself | 2 episodes |

| 2005 | Tripping the Rift | Marvin (voice role) | Episode: "Roswell" |

Awards and nominations

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Klemesrud, Judy (August 2, 1970). "Joe (1970) Movies: His Happiness Is A Thing Called 'Joe'". The New York Times.

- ^ "Past Members of Note". Philadelphia Sketch Club. Archived from the original on December 17, 2012.

- ^ Berkvist, Robert (December 14, 2006). "Peter Boyle, 71, Is Dead; Roles Evoked Laughter and Anger". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ McLellan, Dennis (December 14, 2006). "Peter Boyle, 71; father on 'Raymond'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ McLellan, Dennis (December 14, 2006). "Peter Boyle, 71; father on 'Raymond'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ "Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia: Pete Boyle". Broadcast Pioneers. Retrieved February 1, 2007.(includes 1953 photo)

- ^ a b Berkvist, Robert (December 14, 2006). "Peter Boyle, 71, Is Dead; Roles Evoked Laughter and Anger". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "Biography for Peter Boyle". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 12, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Miller, Stephen (December 14, 2006). "Peter Boyle, 71, Character Actor Played Psychotics and Monsters". The New York Sun. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ Wilkinson, Gerry. "Florence Hanford, a Broadcast Pioneer". Broadcast Pioneers. Archived from the original on November 28, 2006. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ^ "Notable Alumni". HB Studio.

- ^ a b c Bernstein, Adam (December 14, 2006). "Peter Boyle; 'Raymond' Dad Put Some Ritz in 'Young Frankenstein'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ Laster, James H. "Gleason: Production Chronology". All About Wayside Theatre. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ McDonald, George (1996). Frommer's Virginia. Macmillan. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-02860-704-7.

- ^ a b "In Step With: Peter Boyle". Parade Magazine. August 15, 2004.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hajela, Deepti (December 13, 2006). "Obituary: Peter Boyle". Yahoo! News. Retrieved February 1, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Hiltbrand, David (March 21, 2004). "You may love Raymond, but you don't know Peter". The Boston Globe. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ "Joe Bash". JumpTheShark.com. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ Videos, both aired and unaired, are routinely distributed to the music press; this clip appears on fan-made bootleg video compilations: "Roger Waters on Video". Going Underground Magazine. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved February 1, 2007. Reprinted at Pink Floyd RoIO Database: Roger Waters Video Anthology

- ^ "Three Wishes". YouTube. November 27, 2005. Archived from the original on May 19, 2007. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ "Catholic actor Peter Boyle, a former Christian Brother, dies at age 71". Catholic Online. December 14, 2006. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ "TV Land's The 100 Greatest TV Quotes..." Yahoo! Finance. November 22, 2006. Archived from the original on January 23, 2007. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ "Peter Boyle". Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ "Raymond' star Peter Boyle dies at 71". Today.com. Associated Press. December 17, 2006. Archived from the original on March 21, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ Gilsdorf, Ethan (June 3, 2007). "Not the retiring type". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ^ "'Raymond' Cast Mourns Peter Boyle". CBS News. December 13, 2006.

- ^ "Bruce Springsteen & E Street Band - Meeting Across The River". YouTube. January 31, 2008. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "Peter Boyle Fund Annual Comedy Gala". La.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2010.

- ^ "About The Peter Boyle Memorial Fund". Myeloma.org. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- ^ "Nominees / Winners 1977 Emmy Awards". Television Academy. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Nominees / Winners 1989 Emmy Awards". Television Academy. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Nominees / Winners 1996 Emmy Awards". Television Academy. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Nominees / Winners 1999 Emmy Awards". Television Academy. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Nominees / Winners 2000 Emmy Awards". Television Academy. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Nominees / Winners 2001 Emmy Awards". Television Academy. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Nominees / Winners 2002 Emmy Awards". Television Academy. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Nominees / Winners 2003 Emmy Awards". Television Academy. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Nominees / Winners 1977 Emmy Awards". Television Academy. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Nominees / Winners 2005 Emmy Awards". Television Academy. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "5th Screen Actors Guild Awards". Sagawards. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "6th Screen Actors Guild Awards". Sagawards. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "8th Screen Actors Guild Awards". Sagawards. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "9th Screen Actors Guild Awards". Sagawards. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "10th Screen Actors Guild Awards". Sagawards. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "11th Screen Actors Guild Awards". Sagawards. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "12th Screen Actors Guild Awards". Sagawards. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Peter Boyle at the Internet Broadway Database

- Peter Boyle at the Internet Off-Broadway Database (archived)

- Peter Boyle at IMDb

- Peter Boyle at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Peter Boyle at the TCM Movie Database

- MSNBC.com (December 13, 2006): The Daily Nightly: "Remembering Uncle Pete", by Clare Duffy, NBC Nightly News Producer

.jpg/250px-Peter_Boyle_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)