Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Swashbuckler

View on Wikipedia

| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History | ||||||

| Lists and outlines | ||||||

| Theory and criticism | ||||||

|

| ||||||

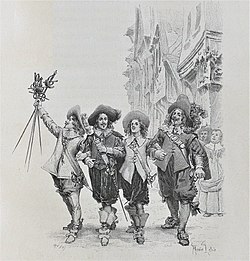

A swashbuckler is a genre of European adventure literature that focuses on a heroic protagonist stock character who is skilled in swordsmanship, acrobatics, and guile, and possesses chivalrous ideals. Swashbuckler protagonists are heroic, daring, and idealistic. They rescue damsels in distress, protect the downtrodden, and use duels to defend their honor or that of a lady or to avenge a comrade.

Swashbucklers often engage in daring and romantic adventures with bravado or flamboyance. Swashbuckler heroes are typically gentleman adventurers who dress elegantly and flamboyantly in coats, waistcoats, tight breeches, large feathered hats, and high leather boots, and they are armed with the thin rapiers that were commonly used by aristocrats.

Swashbucklers are not usually unrepentant brigands or pirates, although some may rise from such disreputable stations and achieve redemption.[1] His opponent is typically characterized as a dastardly villain. While the hero may face down a number of henchmen to the villain during a story, the climax is a dramatic one-on-one sword battle between the protagonist and the villain. There is a long list of swashbucklers who combine courage, skill, resourcefulness, and a distinctive sense of honor and justice, as for example Cyrano de Bergerac, The Three Musketeers, The Scarlet Pimpernel, Robin Hood,[2] and Zorro.[3]

As a historical fiction genre, it is often set in the Renaissance or Cavalier era. The stock character also became common in the film genre, which extended the genre to the Golden Age of Piracy. As swashbuckler stories are often mixed with the romance genre, there will often be a beautiful, aristocratic female love interest to whom the hero expresses a refined, courtly love. At the same time, since swashbuckler plots are often based on intrigues involving corrupt religious figures or scheming monarchs, the heroes may be tempted by alluring femmes fatales or vampish courtesans.

Etymology

[edit]"Swashbuckler" is a compound of "swash" (archaic: to swagger with a drawn sword) and "buckler" (a small shield gripped in the fist) dating from the 16th century.[4][5]

Historical background

[edit]

While man-at-arms and sellswords of the era usually wore armor of necessity, their counterparts in later romantic literature and film (see below) often did not, and the term evolved to denote a daring, devil-may-care demeanor rather than brandishment of accoutrements of war. Swashbuckling adventures and romances are generally set in Europe from the late Renaissance up through the Age of Reason and the Napoleonic Wars, extending into the colonial era with pirate tales in the Caribbean.

Literature

[edit]Jeffrey Richards traces the swashbuckling novel to the rise of Romanticism, and an outgrowth of the historical novel, particularly those of Sir Walter Scott, "... medieval tales of chivalry, love and adventure rediscovered in the eighteenth century".[1] This type of historical novel was further developed by Alexandre Dumas.

John Galsworthy said of Robert Louis Stevenson's 1888 swashbuckling romance, The Black Arrow, that it was "a livelier picture of medieval times than I remember elsewhere in fiction."[6] Anthony Hope's 1894 The Prisoner of Zenda initiated an additional subset of the swashbuckling novel, the Ruritanian romance.[7]

Theatre

[edit]The perceived significant and widespread role of swordsmanship in civilian society as well as warfare in the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods led to fencing being performed on theatre stages as part of plays. Soon actors were taught to fence in an entertaining, dramatic manner. Eventually fencing became an established part of a classical formation for actors.

Movie

[edit]Consequently, when movie theaters mushroomed, ambitious actors took the chance to present their accordant skills on the screen. Since silent movies were no proper medium for long dialogues, the classic stories about heroes who would defend their honour with sword in hand were simplified and sheer action would gain priority. This was the birth of a new kind of film hero: the swashbuckler.[8] For Hollywood actors to depict these skilled sword fighters, they needed advanced sword training. Four of the most famous instructors for swashbuckling swordplay are William Hobbs, Anthony De Longis, Bob Anderson and Peter Diamond.

The larger-than-life heroics portrayed in some film franchise adventures (most notably the Indiana Jones movies) set in the modern era have been described as swashbuckling.[9]

Film

[edit]

The genre has, apart from swordplay, always been characterized by influences that can be traced back to the chivalry tales of Medieval Europe, such as the legends of Robin Hood and King Arthur. It soon created its own drafts based on classic examples like The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Scaramouche (1923) and The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934). Some films did also use motifs of pirate stories.[10] Often these films were adaptations of classic historic novels published by well-known authors such as Alexandre Dumas, Rafael Sabatini, Baroness Emma Orczy, Sir Walter Scott, Johnston McCulley, and Edmond Rostand.

Swashbucklers are one of the most flamboyant Hollywood film genres,[11] unlike cinema verite or modern realistic filmmaking. The genre attracted large audiences who relished the blend of escapist adventure, historic romance, and daring stunts in cinemas before it became a fixture on TV screens. With the focus on action, adventure, and, to a lesser degree, romance, there is little concern for historical accuracy. Filmmakers may mix incidents and events from different historical eras.

As a first variation of the classic swashbuckler there have also been female swashbucklers.[12] Maureen O'Hara in Against All Flags and Jean Peters in Anne of the Indies were very early action film heroines. Eventually the typical swashbuckler motifs were used up because they had so often been shown on TV screens. Later films such as The Princess Bride, the Pirates of the Caribbean series and The Mask of Zorro include modern takes on the swashbuckler archetype.

Television

[edit]Television followed the films, especially in the UK, with The Adventures of Robin Hood, Sword of Freedom, The Buccaneers, and Willam Tell between 1955 and 1960. US TV produced two series of Zorro in 1957 and 1990. Following the 1998 film The Mask of Zorro, a TV series about a female swashbuckler, the Queen of Swords, aired in 2000.[12]

List of characters

[edit]Famous swashbuckler characters from literature and other media include the following:

- Doña María Teresa (Tessa) Alvarado/The Queen of Swords

- D'Artagnan

- Don Diego de la Vega/Zorro

- Alejandro Murieta/Zorro

- Robin Hood

- Peter Pan

- Captain Jack Sparrow

- Puss in Boots

- The Doctor

- Luke Skywalker

- Athos, Porthos, and Aramis

- Captain Hector Barbossa

- Cyrano de Bergerac

- Sir Percy Blakeney/The Scarlet Pimpernel

- Peter Blood

- John Carter of Mars

- Edmond Dantès (The Count of Monte Cristo)

- Ivanhoe

- Indiana Jones

- Diego Alatriste

- Solomon Kane

- Khlit the Cossack

- Don Juan Tenorio

- Fandral

- Captain Harlock

- Kamina

- Marco Del Monte

- Inigo Montoya

- Hiraga Saito

- Andre-Louis Moreau/Scaramouche

- Rudolf Rassendyll

- Dread Pirate Roberts

- Emilio Roccanera (The Black Corsair)

- Sandokan (The Tiger of Malaysia)

- Richard Sharpe

- Alan Breck Stuart

- Dan Tempest

- Guybrush Threepwood

- Dante (Devil May Cry)

- Will Turner

- Elizabeth Swann

- Delilah Dirk

- William Tell

- Lara Croft

- Link (The Legend of Zelda)

- Zuko

- Jamie McCrimmon

- Quentin Durward

- Han Solo

- Nathan Drake (character)

- Sokka

- Reepicheep

- Buck

- Leonardo

- Taylor Earhardt

- Merrick Balinton

- Cameron Watanabe

- Tommy Oliver

- Anubis Doggie Cruger

- Casey Rhodes

- Sir Ivan of Zandar

- Yaz Khan

- Amy Pond

- Rory Williams

- Nightcrawler

- Shang-Chi

- Captain James T. Kirk

- Chiro

- Mihawk

Actors

[edit]Actors notable for their portrayals of swashbucklers include:

- Benoît-Constant Coquelin (1841–1909), was a French actor, and "one of the greatest theatrical figures of the age."[13] He played "Cyrano de Bergerac" over 400 times and later toured North America in the role.

- In early 1883 James O'Neill (1847–1920) took over the lead role in "The Count of Monte Cristo" at Booth's Theater in New York. His interpretation of the part caused a sensation with the theater-going public and a company was immediately set up to take the play on tour. O'Neill bought the rights to the play. "Monte Cristo" remained a popular favorite and would continue to make its appearance on tour as regular as clockwork. O'Neill went on to play this role over 6,000 times.

- E. H. Sothern (1859–1933) was especially known for his heroic portrayal of Rudolph Rassendyl in the first stage adaptation of The Prisoner of Zenda, which he first played in 1895.[14] The role made him a star.

- Douglas Fairbanks (1883–1939) was a Hollywood movie star of the silent film era and was widely regarded as the predecessor to Errol Flynn.

- Errol Flynn (1909–1959) was famously known for the action adventurer typified Hollywood's idea of the swashbuckler in films as Captain Blood (1935), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), and The Sea Hawk (1940).

- Burt Lancaster (1913–1994) Although he was very much an all-round actor, successful in any kind of role, he starred in two swashbuckling films The Flame and the Arrow (1950) and The Crimson Pirate (1952), both produced through his own film production company Norma Productions. Lancaster also starred in and produced two swashbuckler-esque adventure films made in the same time-frame, Ten Tall Men (1951) and His Majesty O'Keefe (filmed in 1952 but released in 1954). Lancaster, a former circus acrobat, was noted for performing his own stunts.[15]

- Mikhail Boyarsky (born 1949), who played d'Artagnan in d'Artagnan and Three Musketeers and its four sequels, as well as other swashbuckler characters in historical adventure movies like Gardes-Marines, Forward!, Viva Gardes-Marines!, Don Cesar de Bazan, The Dog in the Manger, The Prisoner of Château d'If, Queen Margot, among others.

Sources for films

[edit]Fiction writers whose novels and stories have been adapted for swashbuckler films include:

- Bernard Cornwell

- Alexandre Dumas, père

- Jeffery Farnol

- Paul Féval, père

- Théophile Gautier

- Anthony Hope

- Robert E. Howard

- Harold Lamb

- Johnston McCulley

- Baroness Orczy

- Arturo Pérez-Reverte

- Edmond Rostand

- Rafael Sabatini

- William Goldman

- Emilio Salgari

- Sir Walter Scott

- Samuel Shellabarger

- Robert Louis Stevenson

- Michel Zevaco

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Richards, Jeffrey (March 26, 2014). Swordsmen of the Screen: From Douglas Fairbanks to Michael York. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-92863-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Robin Hood Project at the University of Rochester". Robin Hood Project. University of Rochester. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- ^ "The University can lay claim to having its very own Zorro after a student won a prestigious national fencing competition". Archived from the original on 2014-09-15. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- ^ "swashbuckler – Origin and meaning of swashbuckler by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ "The Buckler". The Sussex Rapier School. Archived from the original on 2013-10-07. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ^ Quoted in Edward Wagenknecht, Cavalcade of the English Novel (New York, 1943), 377

- ^ Lancelyn Green, Roger. Introduction to Prisoner of Zenda & Rupert of Hentzau, Everyman's Library. J. M. Dent & Sons, 1966

- ^ "At Sword's Point: Swashbuckling in the Movies". Archived from the original on 2016-07-23. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- ^ "How Indiana Jones Actually Changed Archaeology". nationalgeographic.com. 14 May 2015. Archived from the original on May 17, 2015.

- ^ "Swordplay and Sunken Treasures:The Great Swashbucklers and Pirate Movies". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- ^ "266 Swashbuckling Films". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ a b "Swashbuckling Women of Movies, TV, Theatre, etc". Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- ^ " "Elder Coquelin Dies of Acute Embolism; Great French Actor Was Soon to Appear in Rostand's "Chanticler.", New York Times. January 28, 1909".

- ^ Holder, Heidi J. "Sothern, Edward Askew (1826–1881)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ Krebs, Albin (1994-10-22). "Burt Lancaster, Rugged Circus Acrobat Turned Hollywood Star, Is Dead at 80". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-04-07.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of swashbuckler at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of swashbuckler at Wiktionary