Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

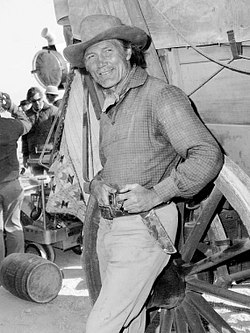

Jack Palance

View on Wikipedia

Walter Jack Palance[1] (/ˈpæləns/ PAL-əns; born Volodymyr Palahniuk; February 18, 1919 – November 10, 2006) was an American screen and stage actor, known to film audiences for playing tough guys and villains. He was nominated for three Academy Awards, all for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, for his roles in Sudden Fear (1952) and Shane (1953), and winning almost 40 years later for City Slickers (1991).

Key Information

Born in Lattimer Mines, Pennsylvania, the son of Ukrainian immigrants, Palance served in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. He attended Stanford University before pursuing a career in the theater, winning a Theatre World Award in 1951. He made his film acting debut in Elia Kazan's Panic in the Streets (1950), and earned Oscar nominations for Sudden Fear and Shane, his third and fourth-ever film roles. He also won an Emmy Award for a 1957 teleplay Requiem for a Heavyweight.

Subsequently, Palance played a variety of both supporting and leading film roles, often appearing in crime dramas and Westerns. Beginning in the late 1950s, he would work extensively in Europe, notably in a memorable turn as a charismatic-but-corrupting Hollywood mogul in Jean-Luc Godard's 1963 film Contempt. He played the title character in the 1973 television film Bram Stoker's Dracula, which influenced future depictions of the character. During the 1980s, he became familiar to a new generation of audiences by hosting the television series Ripley's Believe It or Not! (1982–86). His newfound popularity spurred a late-career revival, and he played high-profile villain roles in the blockbusters Young Guns (1988) and Tango & Cash (1989), and culminating in his Oscar and Golden Globe-winning turn as Curly in City Slickers.

Off-screen, he was involved in efforts in support of the Ukrainian American community and served as a chairman of the Hollywood Trident Foundation.

Early life

[edit]Palance was born Volodymyr Palahniuk on February 18, 1919,[2] in Lattimer Mines, Pennsylvania, the son of Anna (née Gramiak) and Ivan Palahniuk, an anthracite coal miner.[3] His parents were Ukrainian Catholic immigrants,[3][4] his father a native of Ivane-Zolote in southwestern Ukraine (modern Ternopil Oblast) and his mother from the Lviv Oblast.[5][6] One of six children, he worked in coal mines during his youth before becoming a professional boxer in the late 1930s.[7]

Boxing under the name Jack Brazzo, Palahniuk lost his only recorded match, in a four-round decision on points, to future heavyweight contender Joe Baksi in a Pier-6 brawl rough fight.[8][9][10] Other sources record him winning 15 consecutive club fights, with 12 knockouts.[1][7][11] Years later he recounted: "Then I thought, 'You must be nuts to get your head beat in for $200.' The theater seemed a lot more appealing."[12]

World War II

[edit]Palance enlisted in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II, and was trained as the pilot of a B-24 Liberator bomber.[1] He suffered head injuries and burns during a 1943 crash, with various sources citing it as a patrol off the coast of California,[11] or a training flight near Tucson, Arizona (at what is now Davis–Monthan Air Force Base).[1][13] He was discharged in 1944 after undergoing reconstructive surgery, which contributed to his distinctively gaunt appearance.[1]

According to some sources he was awarded a Purple Heart,[7] though he does not appear on official rolls for the decoration. Purple Hearts are not awarded for training injuries.

College

[edit]Palance won a football scholarship to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill but left after two years, disgusted by commercialization of the sport.[14]

After the war, Palance enrolled at Stanford to study journalism, but switched to drama.[7] He left one credit shy of graduating to pursue a career in the theater.[15] During his university years, he worked as a short order cook, waiter, soda jerk, lifeguard at Jones Beach State Park, and a photographer's model.[citation needed]

It was around this time that he changed his name to Walter Jack Palance, reasoning that most people could not pronounce his birth name. His last name was actually a derivative of his original name. In an episode of What's My Line?, he described how no one could pronounce his last name, and how it was suggested that he be called Palanski. From that he decided just to use Palance instead.[16]

Early acting career

[edit]A Streetcar Named Desire

[edit]In New York City, Palance studied method acting under Michael Chekhov,[17] while working as a sportswriter. He made his Broadway debut in 1947 as a Russian soldier in The Big Two, directed by Robert Montgomery.[18]

Palance's acting break came as Marlon Brando's understudy in A Streetcar Named Desire, and he eventually replaced Brando on stage as Stanley Kowalski. (Anthony Quinn, however, gained the opportunity to tour the play.)[19]

Palance appeared in two plays in 1948 with short runs, A Temporary Island and The Vigil. He made his television debut in 1949.[20]

Film career

[edit]Palance made his big-screen debut in Panic in the Streets (1950), directed by Elia Kazan, who had directed Streetcar on Broadway. He played a gangster, and was credited as "Walter (Jack) Palance".

That year he was featured in Halls of Montezuma (1951), about United States Marines during World War II. He returned to Broadway for Darkness at Noon (1951) by Sidney Kingsley, which was a minor hit.

Two Oscar nominations

[edit]Palance was second-billed in just his third film, opposite Joan Crawford in the thriller Sudden Fear (1952). His character is a former coal miner, as Palance's father had been.[21] Palance received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor.[22]

He was nominated in the same category the following year for his role as hired gunfighter Jack Wilson in Shane (1953).[23][24] The film was a huge hit, and Palance was now an established film name.[citation needed]

Stardom

[edit]Palance played a villain in Second Chance opposite Robert Mitchum, and was a Native in Arrowhead (both 1953). He got a chance to play a heroic role in Flight to Tangier (1953), a thriller.[25]

He played the lead in Man in the Attic (1953), an adaptation of The Lodger. He was Attila the Hun in Sign of the Pagan with Jeff Chandler, and Simon Magus in the Ancient World epic The Silver Chalice (both 1954) with Paul Newman(who disowned his participation in the film).[26]

He had the star part in I Died a Thousand Times (1955), a remake of High Sierra, and was cast by Robert Aldrich in two star parts: The Big Knife (1955), from the play by Clifford Odets, as a Hollywood star; and Attack (1956), as a tough soldier in World War II.

In 1955, he had an operation for appendicitis.[27]

Palance was in a Western, The Lonely Man (1957), playing the father of Anthony Perkins, and played a double role in House of Numbers (1957).

In 1957, Palance won an Emmy Award for best actor for his portrayal of Mountain McClintock in the Playhouse 90 production of Rod Serling's Requiem for a Heavyweight.[28]

International star

[edit]Warwick Films hired Palance to play the hero in The Man Inside (1958), shot in Europe. He was reunited with Robert Aldrich and Jeff Chandler when they worked on Ten Seconds to Hell (1959), filmed in Germany, playing a bomb disposal expert.

He made Beyond All Limits (1959) in Mexico, and Austerlitz (1960) in France, then did a series of films in Italy: Revak the Rebel, Sword of the Conqueror, The Mongols, The Last Judgment, and Barabbas (all 1961), and Night Train to Milan and Warriors Five (both 1962). Jean-Luc Godard persuaded Palance to take on the role of Hollywood producer Jeremy Prokosch in the nouvelle vague movie Le Mépris (1963) with Brigitte Bardot. Although the main dialogue was in French, Palance spoke mostly English.[citation needed]

Return to Hollywood

[edit]Palance returned to the U.S. to star in the TV series The Greatest Show on Earth (1963–64).[29] In 1964, his presence at a recently integrated movie theater in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, prompted a riot from segregationists who assumed Palance was there to promote civil rights.[30]

He played a gangster in Once a Thief (1965) with Alain Delon. In the following year he appeared in the television film Alice Through the Looking Glass, directed by Alan Handley, in which he played the Jabberwock, and had a featured role opposite Lee Marvin and Burt Lancaster in the Western adventure The Professionals. Palance guest-starred in The Man from U.N.C.L.E., and the episodes were released as a film, The Spy in the Green Hat (1967). He went to England to make Torture Garden (1967), and made Kill a Dragon (1968) in Hong Kong.

Palance provided narration for the 1967 documentary And Still Champion! The Story of Archie Moore. He was in the TV film The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde produced by Dan Curtis, during the making of which he fell and injured himself.[31]

In 1969, Palance recorded a country music album in Nashville, released on Warner Bros. Records. It featured his self-penned song "The Meanest Guy that Ever Lived". The album was re-released on CD in 2003 by the Water label (Water 119). His films were often international co-productions by this time: They Came to Rob Las Vegas, The Mercenary (both 1968), The Desperados, and Marquis de Sade: Justine (both 1969).

Palance had a part in the Hollywood blockbuster Che! (1969) playing Fidel Castro opposite Omar Sharif in the title role, but the film flopped. Palance went back to action films and Westerns: Battle of the Commandos (1970), The McMasters (1970) and Compañeros (1970).

Palance had another role in Monte Walsh (1970), from the author of Shane, opposite Lee Marvin, but the film was a box-office disappointment. So too was The Horsemen (1971) with Sharif, directed by John Frankenheimer. He supported Bud Spencer in It Can Be Done Amigo and Charles Bronson in Chato's Land (both 1972), and had the lead in Sting of the West (1972) and Brothers Blue (1973).[citation needed]

In Great Britain he appeared in a highly acclaimed TV film, Bram Stoker's Dracula (1973), in the title role; it was directed by Dan Curtis. Three years earlier, comic book artist Gene Colan had based his interpretation of Dracula for the acclaimed Marvel Comics comic book series The Tomb of Dracula on Palance, explaining, "He had that cadaverous look, a serpentine look on his face. I knew that Jack Palance would do the perfect Dracula."[32]

Palance went back to Hollywood for Oklahoma Crude (1973) then to England to star in Craze (1974). He starred in the television series Bronk between 1975 and 1976 for MGM Television, and starred in the TV films The Hatfields and the McCoys (1975) and The Four Deuces (1976).[citation needed]

Italy

[edit]In the late 1970s, Palance was mostly based in Italy. He supported Ursula Andress in Africa Express and The Sensuous Nurse, Lee Van Cleef in God's Gun, and Thomas Milian in The Cop in Blue Jeans (all 1976). He was in Black Cobra Woman; Safari Express, a sequel to Africa Express; Mister Scarface; and Blood and Bullets (all 1976). He traveled to Canada to make Welcome to Blood City (1977) and the US for The One Man Jury (1978), Portrait of a Hitman and Angels Revenge (both 1979).

Palance later said his Italian sojourn was the most enjoyable of his career. "In Italy, everyone on the set has a drinking cubicle, and no one is ever interested in working after lunch", he said. "That's a highly civilized way to make a movie."[33] He went back to Canada for H. G. Wells' The Shape of Things to Come (1979).[34]

Return to the U.S. and Ripley's Believe It or Not!

[edit]In 1980, Jack Palance narrated the documentary The Strongest Man in the World by Canadian filmmaker Halya Kuchmij, about Mike Swistun, a circus strongman who had been a student of Houdini. Palance attended the premiere of the film on June 6, 1980, at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.[35] He appeared in The Ivory Ape (1980), Without Warning (1980), Hawk the Slayer (1980), and the slasher film, Alone in the Dark (1982).

In 1982, Palance began hosting a television revival of Ripley's Believe It or Not!. The weekly series ran from 1982 to 1986 on the American ABC network. The series also starred three different co-hosts from season to season, including Palance's daughter Holly Palance, actress Catherine Shirriff and singer Marie Osmond. Ripley's Believe It or Not! was in rerun syndication on the Sci-fi Channel (UK) and the Sci-fi Channel (U.S.) during the 1990s. He appeared in the films Gor and Bagdad Café (both 1987).[citation needed]

Later career

[edit]Career revival

[edit]Palance had never been out of work since his career began, but his success on Ripley's Believe It or Not! and the international popularity of Bagdad Cafe (1987) created a new demand for his services in big-budget Hollywood films.

He made memorable appearances as villains in Young Guns (1988) as Lawrence Murphy, Tango & Cash (1989) and Tim Burton's Batman (1989). He also performed on Roger Waters' first solo album release, The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking (1984), and was in Outlaw of Gor (1988) and Solar Crisis (1990).

City Slickers

[edit]Palance was then cast as cowboy Curly Washburn in the 1991 comedy City Slickers, directed by Ron Underwood. He quipped:

I don't go to California much any more. I live on a farm in Pennsylvania, about 100 miles from New York, so I can go into the city for dinner and a show when I want to. I also have a ranch about two hours from Los Angeles, but I don't go there very often at all...But I will always read a decent script when it is offered, and the script to City Slickers made sense. Curly (his character in the film) is the kind of man I would like to be. He is in control of himself, except for deciding the moment of his own death. Besides all that, I got paid pretty good money to make it.[33]

Four decades after his film debut, Palance won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor on March 30, 1992, for his performance as Curly.[36] Stepping onstage to accept the award, the 6-foot-4-inch (1.93 m) actor looked down at 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) Oscar host Billy Crystal (who was also his co-star in the movie) and joked, mimicking one of his lines from the film, "Billy Crystal ... I crap bigger than him." He then dropped to the floor and demonstrated his ability, at the age of 73, to perform one-armed push-ups.[citation needed]

The audience loved the moment and host Crystal turned it into a running gag. At various points in the broadcast, Crystal announced that Palance was "backstage on the StairMaster", had bungee-jumped off the Hollywood sign, had rendezvoused with the space shuttle in orbit, had fathered all the children in a production number, had been named People magazine's "Sexiest Man Alive", and had won the New York primary election. At the end of the broadcast Crystal said he wished he could be back next year, but "I've just been informed Jack Palance will be hosting."[citation needed]

Years later, Crystal appeared on Inside the Actors Studio and fondly recalled that, after the Oscar ceremony, Palance approached him during the reception: "He stopped me and put his arms out and went, 'Billy Crystal, who thought it would be you?' It was his really funny way of saying thank you to a little New York Jewy guy who got him the Oscars."[37]

In 1993, during the opening of the Oscars, a spoof of that Oscar highlight featured Palance appearing to drag in an enormous Academy Award statuette with Crystal again hosting, riding on the rear end of it. Halfway across the stage, Palance dropped to the ground as if exhausted, but then performed several one-armed push-ups before regaining his feet and dragging the giant Oscar the rest of the way across the stage.[38]

He appeared in Cyborg 2 (1993); Cops & Robbersons (1994) with Chevy Chase; City Slickers II: The Legend of Curly's Gold (1994); and on TV in Buffalo Girls (1995). He also voiced Rothbart in the 1994 animated film The Swan Princess.

Final years

[edit]Palance's final films included Ebenezer (1998), a TV Western version of Charles Dickens's classic A Christmas Carol, with Palance as Scrooge; Treasure Island (1999); Sarah, Plain and Tall: Winter's End (2000); and Prancer Returns (2001).

Palance, at the time chairman of the Hollywood Trident Foundation, walked out of a Russian Film Festival in Hollywood in 2004. After being introduced, Palance said, "I feel like I walked into the wrong room by mistake. I think that Russian film is interesting, but I have nothing to do with Russia or Russian film. My parents were born in Ukraine: I'm Ukrainian. I'm not Russian. So, excuse me, but I don't belong here. It's best if we leave."[39] Palance was awarded the title of "People's Artist" by Vladimir Putin, president of Russia; however, Palance refused it.[39]

In 2001, Palance returned to the recording studio as a special guest on friend Laurie Z's album Heart of the Holidays to narrate the classic poem "The Night Before Christmas". In 2002, he starred in the television movie Living with the Dead opposite Ted Danson, Mary Steenburgen and Diane Ladd. In 2004, he starred in another television production, Back When We Were Grownups, once again directed by Ron Underwood, opposite Blythe Danner; it was his final performance.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

Palance lived for several years around Tehachapi, California. He was married to his first wife, Virginia (née Baker), from 1949 to 1968. They had three children, of whom Holly Palance and Brooke Palance became actors. On New Year's Day, 2003, Virginia was struck and killed by a car in Los Angeles. In May 1987, Palance married his second wife, Elaine Rogers. His death certificate listed his marital status as "Divorced".

Palance painted and sold landscape art, with a poem included on the back of each picture. He was also the author of The Forest of Love, a book of poems published in 1996 by Summerhouse Press.[40]

Palance enjoyed raising cattle on his ranch in the Tehachapi Mountains.[41] He gave up eating red meat after working on his ranch, commenting that he couldn't eat a cow.[42]

Palance acknowledged a lifelong attachment to his Pennsylvania heritage and visited there when able. Shortly before his death, he sold his farm in Butler Township and put his art collection up for auction.[43]

Death

[edit]Palance died at the age of 87 from natural causes at his daughter Holly's house in Montecito, California on November 10, 2006.[44] Following his death a memorial service was held at St. Michael's Ukrainian Catholic Church in Hazleton, Pennsylvania.[45]

Legacy

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2024) |

Palance has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6608 Hollywood Boulevard.[46]

In 1992, he was inducted into the Western Performers Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.[47]

According to writer Mark Evanier, comic book creator Jack Kirby modeled his character Darkseid on the actor.[48]

The Lucky Luke 1956 comic Lucky Luke contre Phil Defer by Morris features a villain named Phil Defer who is a caricature of Jack Palance.

The song "And now we dance" by punk band The Vandals features the lyrics, "Come on and do one hand pushups just like Jack Palance."

American comedian Bill Hicks incorporated a reference to Palance in one of his most famous routines, likening Palance's character in Shane to how he views the United States' role in international warfare.[49]

Novelist Donald E. Westlake stated that he sometimes imagined Palance as the model for the career-criminal character Parker he wrote in a series of novels under the name Richard Stark.[50]

In 2023, Palance was inducted into the Luzerne County Arts & Entertainment Hall of Fame. He was included among the inaugural class of inductees.[51]

Filmography

[edit]Films

[edit]Television

[edit]Series

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Lights Out | Episode: "The Man Who Couldn't Remember" | |

| 1952 | Westinghouse Studio One | Episode: "The King in Yellow" | |

| Curtain Call | Episode: "Azaya" | ||

| Westinghouse Studio One | Episode: "Little Man, Big World" | ||

| The Gulf Playhouse | Episode: "Necktie Party" | ||

| 1953 | Danger | Episode: "Said the Spider to the Fly" | |

| The Web | Episode: "The Last Chance" | ||

| Suspense | Tom Walker | Episode: "The Kiss-Off" | |

| The Motorola Television Hour | Scott Malone / Kurt Bauman | Episode: "Brandenburg Gate" | |

| Suspense | Episode: "Cagliostro and the Chess Player" | ||

| 1955 | What's My Line | Himself | 1 episode |

| 1956 | Playhouse 90 | Harlan 'Mountain' McClintock | Episode: "Requiem for a Heavyweight" Emmy Award for Best Single Performance by an Actor |

| Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theatre | Dan Morgan | Episode: "The Lariat" opposite Constance Ford | |

| 1957 | Playhouse 90 | Monroe Stahr | "The Last Tycoon" |

| Manolete | "The Death of Manolete" | ||

| 1963 | The Greatest Show on Earth | Circus Manager Johnny Slate | Series – top billing, 30 episodes |

| 1964 | What's My Line | Himself | Mystery guest |

| 1965 | Convoy | Harvey Bell | Episode: "The Many Colors of Courage" |

| 1966 | Run for Your Life | Julian Hays | Episode: "I Am the Late Diana Hays" |

| Alice Through the Looking Glass | Jabberwock | (Live Theatre) | |

| The Man from U.N.C.L.E. | Louis Strago | 2 episodes "The Concrete Overcoat Affair: Parts I and II" (reedited as The Spy in the Green Hat) | |

| 1971 | Net Playhouse | President Jackson | "Trail of Tears" |

| 1973 | The Sonny & Cher Comedy Hour | Himself | |

| 1975–76 | Bronk | Lieutenant Alex 'Bronk' Bronkov | Series – top billing, 25 episodes |

| 1979 | Buck Rogers in the 25th Century | Kaleel | Episode: "Planet of the Slave Girls" |

| Unknown Powers | Presenter/Narrator | ||

| 1981 | Tales of the Haunted | Stokes | Episode: "Evil Stalks This House" |

| 1982–86 | Ripley's Believe It or Not! | Himself – Host | Series |

| 2001 | Night Visions | Jake Jennings | Segment: "Bitter Harvest" |

Movies/miniseries

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Requiem for a Heavyweight | Harlan 'Mountain' McClintock | |

| 1966 | Alice Through the Looking Glass | Jabberwock | [52] |

| 1968 | The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde | Dr. Henry Jekyll / Mr. Edward Hyde | |

| 1974 | Bram Stoker's Dracula | Count Dracula | |

| The Godchild | Rourke | ||

| 1975 | The Hatfields and the McCoys | Anderson 'Devil Anse' Hatfield | |

| 1979 | The Last Ride of the Dalton Gang | Will Smith | |

| 1980 | The Ivory Ape | Marc Kazarian | |

| The Golden Moment: An Olympic Love Story | 'Whitey' Robinson | ||

| 1981 | Evil Stalks This House | Stokes | |

| 1992 | Keep the Change | Overstreet | |

| 1994 | Twilight Zone: Rod Serling's Lost Classics | Dr. Jeremy Wheaton | (segment "Where the Dead Are") |

| 1995 | Buffalo Girls | Bartle Bone | |

| 1997 | I'll Be Home for Christmas | Bob | |

| 1998 | Ebenezer | Ebenezer Scrooge | |

| 1999 | Sarah, Plain and Tall: Winter's End | John Witting | |

| 2001 | Living With the Dead | Allan Van Praagh | |

| 2004 | Back When We Were Grownups | Paul 'Poppy' Davitch | (final film role) |

Stage

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Venue | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | The Big Two | Russian soldier | Booth Theatre, Broadway | [53] |

| 1948 | A Temporary Island | Mr. Boutourlinsky | Maxine Elliott's Theatre, Broadway | [54] |

| 1948 | The Vigil | Simon | Royale Theatre, Broadway | [55] |

| 1948 | A Streetcar Named Desire | Stanley Kowalski (understudy, replacement) | Ethel Barrymore Theatre, Broadway | [56][57] |

| 1951 | Darkness at Noon | Gletkin | Alvin Theatre, Broadway | [58] |

| Royale Theatre, Broadway | ||||

| 1955 | Julius Caesar | Cassius | American Shakespeare Theatre, Connecticut | [59][60] |

| 1955 | The Tempest | Caliban | American Shakespeare Theatre, Connecticut | [60] |

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Association | Year | Category | Nominated work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | 1953 | Best Supporting Actor | Sudden Fear | Nominated |

| 1954 | Shane | Nominated | ||

| 1992 | City Slickers | Won | ||

| American Comedy Awards | 1992 | Funniest Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture | Won | |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Award | Best Supporting Actor | Nominated | ||

| DVD Exclusive Awards | 2001 | Prancer Returns | Won | |

| Golden Globe Awards | 1992 | Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | City Slickers | Won |

| Golden Boot Awards | 1993 | Golden Boot | Won | |

| National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum | Bronze Wrangler – Factual Narrative | Legends of the West | Won | |

| Primetime Emmy Awards | 1957 | Best Single Performance by an Actor | Playhouse 90 | Won |

| Theater World Award[61] | 1951 | Outstanding New York City Stage Debut | Darkness at Noon | Won |

| WorldFest Flagstaff | 1998 | Lifetime Achievement Award | Won | |

| Online Film & Television Association Award | 2004 | Best Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture or Miniseries | Back When We Were Grownups | Nominated |

| 20/20 Award | 2012 | Best Supporting Actor | City Slickers | Nominated |

Discography

[edit]- Palance, Warner Bros, 1969[62]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Shadow box". airforce.togetherweserved.com. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ Some sources, inclusive his Santa Barbara County (California) death certificate, cite 1920 as Palance's year of birth.

- ^ a b "The Last Role of an American "City Slicker" with a Ukrainian Soul". Ukemonde.com. November 14, 2006. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ "Entertainment | Veteran western star Palance dies". BBC News. November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ A History of the Polish Americans. Transaction Publishers. 1987. p. 113. ISBN 9781412825443. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Matthew Dubas, "OBITUARY: Academy Award-winning actor Jack Palance, 87", The Ukrainian Weekly, November 19, 2006

- ^ a b c d magazine, STANFORD (January 1, 2007). "Requiem for a Heavy". stanfordmag.org. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Official records only show Palance in one sanctioned fight. His other fights may have been club fights, boxrec.com. Accessed September 10, 2022.

- ^ Schmidt, M.A., "Palance From Panic To Pagan", The New York Times, March 14, 1954, X5. In an early interview, Palance claimed to have fought Baksi to a draw.

- ^ Enk, Bryan. "Real Life Tough Guys". Yahoo.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ a b "Pennsylvania Center for the Book". pabook.libraries.psu.edu. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ Lawrence Christon, "Home on the Range It's been a long, dusty journey since Panic in the Streets and Shane", Los Angeles Times, April 30, 1995. (In a later interview, Palance admits to have lost to Baksi.)

- ^ "Legacy: Jack Palance". EW.com. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ "Jack Palance Obituary". AP. November 10, 2006.

- ^ "Accomplished Alumni – School of Humanities and Sciences". Humsci.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ "YouTube". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 28, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ "Michael Chekhov and His Approach to Acting in Contemporary Performance Training". University of Maine. Retrieved July 8, 2025.

- ^ The Life Story of Jack Palance Picture Show; London Vol. 62, Iss. 1605, (January 2, 1954): 12.

- ^ The New Yorker. F-R Publishing Corporation. 1992. p. 76.

- ^ Monush, Barry (April 1, 2003). The Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors: From the Silent Era to 1965. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 581. ISBN 978-1-4803-2998-0.

- ^ Sudden Fear, 1952.

- ^ Palance from 'Panic to Pagan' By M. A. Schmidt Hollywood.. New York Times March 14, 1954: X5.

- ^ Schaefer, Jack (January 1, 1984). Shane: The Critical Edition. U of Nebraska Press. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-8032-9142-3.

- ^ Stratton, W. K. (February 12, 2019). The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah, a Revolution in Hollywood, and the Making of a Legendary Film. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-63286-214-3.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda, "Menace Jack Palance Cast as Apache Chief", Los Angeles Times, October 17, 1952, B6.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K., "Jack Palance as Attila Dominant 'Pagan' Figure", Los Angeles Times, December 24, 1954, p. 10.

- ^ "Jack Palance Has Operation", The New York Times, October 19, 1955: 39.

- ^ Coppola, Jo (March 22, 1957). "Palance Scores Again". Newsday. p. 3C. ProQuest 879938015.

When Jack Palance accepted the Emmy Award Saturday for his role as Mountain, the washed-up fighter in 'Requiem for a Heavyweight' done on 'Playhouse 90' in October, his diction was as precise as a diamond cutter's hand when handling a 100-carat gem.

- ^ Page, Don, "Jack Palance: In the center ring", Los Angeles Times, September 1, 1963, p. C3.

- ^ "Jack Palance Presence Sparks Tuscaloosa Riot", Los Angeles Times, July 11, 1964, p. 7

- ^ "Jack Palance Injured in Stunt Mishap", Los Angeles Times, September 9, 1967, B5.

- ^ Field, Tom (2005). Secrets in the Shadows: The Art & Life of Gene Colan. Raleigh, NC: TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 99.

- ^ a b Wuntch, Philip, "Jack Palance's Image Follows Him Offscreen", Sun Sentinel, July 3, 1991: 3E.

- ^ Shales, Tom, "Jack Palance: The Tough Guy Behind the Tough-Guy Exterior: Jack Palance", The Washington Post, August 22, 1980, C1.

- ^ "Strongest Man In The World on Vimeo". Vimeo.com. October 7, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Martin, Douglas, "Jack Palance, Living the Western", The New York Times, July 21, 1991, A17.

- ^ Video on YouTube

- ^ Grimes, William (March 30, 1993). "Eastwood Western Takes Top 2 Prizes In 65th Oscar Show". The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ a b "Declaring 'I'm Ukrainian, not Russian', Palance walks out of Russian Film Festival in Hollywood". Ukemonde.com. June 11, 2004. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ The Forest of Love. Summerhouse Press. January 1, 1996. ISBN 9781887714075. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ "Jack Palance, 87; gravelly voiced actor won Oscar as crusty trail boss in 'City Slickers'". latimes.com. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Tough Guys Write Poetry Book Reflects Softer Side of Actor Jack Palance". mcall.com. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ Learn-Andes, Jennifer (October 8, 2006). "Jump on Jack's stash". Times Leader. Archived from the original on October 19, 2006. Retrieved October 8, 2006.

- ^ "Oscar winner Jack Palance dead at 87". CNN. November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ "Hazleton Mass Set For Palance, The Local Boy Who Made It Big In Films". Times Leader. May 22, 2007. Retrieved March 31, 2025.

- ^ Chad (October 25, 2019). "Jack Palance". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ "Jack Palance - Trivia". IMDb. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Sommerlad, Joe (February 26, 2019). "Bill Hicks 25 years on: The stand-up comedian whose uncompromising attack held the powerful to account". The Independent. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ "Interview with Donald Westlake, author of the Parker novels". The University of Chicago Press. 2008. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ "Luzerne County Arts & Entertainment Hall of Fame Announces inaugural class", timesleader.com. Accessed June 2, 2024.

- ^ Vlastnik, Frank; Ross, Laura (November 16, 2021). The Art of Bob Mackie. Simon and Schuster. pp. 23–25. ISBN 978-1-9821-5211-6.

- ^ "The Big Two – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ "A Temporary Island – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ "The Vigil – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ "A Streetcar Named Desire – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ Severo, Richard (November 11, 2006). "Jack Palance, 87, Film and TV Actor, Dies". New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ "Darkness at Noon – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ Rueb, Emily S. (January 13, 2019). "Shakespeare Theater in Stratford, Conn., Is Destroyed by Fire". New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ a b Cooper, Roberta Krensky (1986). The American Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford 1955-1985. Washington: Folger Books. p. 282. ISBN 0918016886. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ "Jack Palance – Broadway Cast & Staff". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ "Jack Palance". All Music. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

External links

[edit]Jack Palance

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Family Background and Childhood

Jack Palance was born Volodymyr Palahniuk on February 18, 1919, in Lattimer Mines, a small anthracite coal mining community in Hazle Township, Luzerne County, Pennsylvania.[1] His parents were Ukrainian immigrants: father Ivan Palahniuk, who worked as an anthracite coal miner, originated from Ivane Zolote in southwestern Ukraine (modern Ternopil Oblast), and mother Anna (née Gramiak) came from the Lviv region.[2][1] The family's relocation to the United States placed them in a rugged industrial enclave dominated by Eastern European immigrant labor, where coal extraction shaped daily existence amid frequent labor disputes and hazardous conditions.[2] As the sixth of six children born to Ivan and Anna, young Volodymyr grew up in relative poverty typical of mining households, with his father's occupation providing unstable income vulnerable to market fluctuations and health risks like black lung disease.[1] Siblings included at least three brothers—John, Ivan Jr., and another unnamed in records—though family dynamics emphasized self-reliance in the face of economic precarity.[8] The Palahniuks maintained strong Ukrainian cultural ties, including language and traditions, in a community where such immigrant enclaves preserved ethnic identities amid assimilation pressures.[2] Palance later recalled the formative influence of this environment, marked by physical toughness and limited formal opportunities, fostering his early interest in athletics over scholarly pursuits.[1]Boxing and Athletic Beginnings

Born Volodymyr Palahniuk in the coal-mining region of Lattimer Mines, Pennsylvania, Palance labored in the anthracite mines during his youth, developing a robust physique through demanding physical work.[1] He turned to boxing as an outlet for his athletic inclinations in his late teens, competing initially in unsanctioned or amateur bouts amid the harsh economic conditions of the Great Depression-era mining towns.[9] Standing at 6 feet 3 inches and weighing around 200 pounds, he entered the heavyweight division, drawn to the sport's promise of quick earnings and a path beyond manual labor.[10] In the late 1930s, Palahniuk adopted the professional ring name Jack Brazzo and fought in regional Pennsylvania circuits, often against local club fighters in coal-mining communities.[3] Contemporary accounts and later biographies report that he amassed an unverified string of successes, with claims of 15 wins—including 12 by knockout—prior to a setback, though these early matches lack comprehensive documentation in official records.[2] [11] The sole bout preserved in boxing archives occurred on December 17, 1940, in Kingston, New York, where Brazzo suffered a four-round unanimous decision loss to Joe Baksi, an emerging heavyweight who later challenged for titles against figures like Tami Mauriello.[10] This defeat marked the end of his documented professional career, after which Palance shifted focus amid escalating global tensions leading to World War II.[11] Palance's brief pugilistic foray honed his resilience and commanding presence, attributes rooted in first-hand experience with the sport's rigors rather than mere anecdote, though the paucity of verified records underscores the informal nature of Depression-era regional boxing.[11] No evidence indicates participation in other organized athletics, such as football or wrestling, during this period; his endeavors centered on boxing as a pragmatic pursuit in a working-class milieu.[1]World War II Service

Palance enlisted in the United States Army Air Forces in August 1942, shortly after the United States entered World War II, ending his brief professional boxing career.[4][12] He underwent pilot training in San Antonio, Texas, qualifying as a pilot for the B-24 Liberator heavy bomber.[12][13] Assigned to the 455th Bomb Group of the U.S. Army Air Corps, Palance served as a bomber pilot in the European Theater of Operations.[14] In 1943, during a training flight near Tucson, Arizona, his B-24 caught fire and crashed on takeoff after an outboard engine failed, resulting in severe facial burns, head injuries, and other trauma that required extensive reconstructive surgery.[12][15][13] He was awarded the Purple Heart for these wounds.[15] The injuries led to a two-year hospitalization and medical discharge from the service, after which Palance pursued acting, leveraging his altered facial features for dramatic roles.[4][14]Post-War Education and Training

After his honorable discharge from the U.S. Army Air Forces at the end of World War II, Palance enrolled at Stanford University using the G.I. Bill benefits, initially studying journalism with aspirations of becoming a sportswriter.[16][4] While at Stanford, he contributed as a sportswriter for the San Francisco Chronicle and worked at a radio station in Palo Alto, supplementing his education with practical media experience.[1] Palance soon transitioned his academic focus from journalism to drama, recognizing his aptitude for theatrical expression amid the university's offerings in the performing arts.[15] He supported himself through various odd jobs, including as a cook, waiter, and lifeguard, during this period of self-directed exploration into acting.[17] Departing Stanford one credit shy of earning his degree, Palance relocated to New York City in the late 1940s to seek professional opportunities in theater, driven by a longstanding urge "to express myself through words."[18][19][20] This shift marked the culmination of his informal post-war training, bridging his military service and nascent stage ambitions without formal enrollment in specialized dramatic academies beyond Stanford's program.Acting Career Beginnings

Dramatic Schooling and Stage Entry

Following World War II service, Palance utilized the G.I. Bill to attend Stanford University, initially pursuing journalism before shifting focus to drama studies.[15] He departed the institution one credit short of completing his degree in 1947 to relocate to New York City and commit to a theatrical career.[18] In New York, Palance trained in method acting techniques under the guidance of Michael Chekhov, a Russian émigré director and actor known for developing a psycho-physical approach emphasizing imagination and gesture over strict emotional recall.[21] To support himself during this period, he worked as a sportswriter, honing observational skills that later informed his character portrayals.[22] Palance made his Broadway debut on January 8, 1947, in the short-lived play The Big Two at the Booth Theatre, portraying a Russian soldier in a World War II-era drama about divided loyalties; the production closed after 18 performances on January 25. This initial stage appearance marked his professional entry into theater, preceding more prominent opportunities.[23]Broadway Breakthrough: A Streetcar Named Desire

Palance secured his position as understudy for Marlon Brando in the role of Stanley Kowalski in the original Broadway production of A Streetcar Named Desire, which premiered on December 3, 1947, at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre and ran for 409 performances until December 17, 1949.[24][25] This opportunity followed his minor Broadway debut earlier in 1947 as a Russian soldier in The Big Two.[1] The pivotal moment came when Brando, sidelined by a broken nose sustained during a sparring session, could not perform, prompting Palance to assume the lead role onstage.[18][5] Palance later took on Stanley Kowalski as an official replacement during the production's extended run, delivering performances that highlighted his physical intensity and dramatic presence in Tennessee Williams's portrayal of the brutish, working-class antagonist.[25] Critics noted Palance's commanding interpretation, which emphasized the character's raw aggression and contrasted with Brando's more nuanced magnetism, earning praise that propelled his transition to film.[26] These reviews directly facilitated his signing with 20th Century Fox, marking A Streetcar Named Desire as the catalyst for Palance's emergence from stage understudy to recognized talent capable of anchoring a landmark dramatic work.[1][23]Initial Film Roles

Palance transitioned to film shortly after his Broadway success, securing his screen debut in Elia Kazan's Panic in the Streets (1950), where he was billed as Walter Jack Palance and portrayed Blackie, a ruthless gangster involved in a murder tied to a pneumonic plague outbreak in New Orleans.[27][28] The role capitalized on his physical intensity and understudy experience with Kazan from A Streetcar Named Desire, marking his entry into Hollywood as a menacing supporting player in a film noir thriller that emphasized on-location shooting and public health urgency.[29] His next significant role came in Sudden Fear (1952), a psychological thriller directed by David Miller, in which Palance played Irene's husband, a scheming opportunist plotting her demise alongside Gloria Grahame, earning him his first Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor on July 16, 1953.[30] The performance showcased his ability to convey cold calculation and betrayal, contributing to the film's tension amid its San Francisco setting and themes of jealousy and greed.[31] Palance continued with antagonistic parts in quick succession, including the villainous gunslinger Jack Wilson in George Stevens' Western Shane (1953), which brought a second Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor in 1954 and solidified his image as a formidable heavy through stark physical presence and sparse dialogue.[30] These early films, totaling just four by mid-decade, established him in Hollywood despite limited screen time, often leveraging his boxing background for authentic toughness in roles that contrasted heroic leads like Richard Widmark and Alan Ladd.[32]Rise in Hollywood and Early Acclaim

Key 1950s Films and Oscar Nominations

Palance's transition to film in the early 1950s marked his rapid ascent, beginning with supporting roles that showcased his intense screen presence. His breakthrough came in Sudden Fear (1952), a film noir directed by David Miller, where he portrayed Lester Blaine, an ambitious actor who marries wealthy playwright Myra Hudson (Joan Crawford) and subsequently plots her murder with his mistress.[33] The performance, noted for its chilling duplicity and physical menace, earned Palance his first Academy Award nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role at the 25th Academy Awards on March 19, 1953.[34] The following year, Palance delivered another standout villainous turn as Jack Wilson, a cold-blooded gunslinger, in George Stevens' Western Shane (1953), starring Alan Ladd as the titular drifter aiding homesteaders against cattle barons. Released on August 22, 1953, the film featured Palance's character as the enforcer for rancher Rufus Ryker, culminating in a iconic shootout that highlighted his economical yet terrifying physicality. This role secured Palance's second consecutive Oscar nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role at the 26th Academy Awards on March 25, 1954, though he lost to William Holden for Stalag 17.[35] Shane itself received six nominations, including Best Picture, underscoring the film's enduring status as a genre exemplar.[35] Beyond these acclaimed works, Palance took his first leading role in Man in the Attic (1953), a suspense thriller remake of The Lodger where he played Slade, a suspect in Jack the Ripper killings, demonstrating his versatility in horror-tinged drama.[30] In The Big Knife (1955), directed by Robert Aldrich and adapted from Clifford Odets' play, Palance starred as Charlie Castle, a disillusioned Hollywood actor grappling with moral compromise and studio pressure, a role that mirrored industry critiques and further established his dramatic range.[5] These 1950s films solidified Palance's reputation for portraying complex antagonists, leveraging his imposing 6-foot-4 frame and angular features, though the back-to-back nominations highlighted his potential beyond typecasting.[36]Typecasting as Antagonist Roles

Palance's craggy features, honed by a professional boxing career that left facial scars and an intense, piercing gaze, along with his experiences in Pennsylvania's hard-coal mines, positioned him for typecasting as Hollywood's quintessential antagonist in the 1950s.[37][18] His physical menace and gravelly voice made him ideal for roles demanding quiet intimidation and explosive violence, leading to villains in approximately 90 percent of his early films.[37] Breakthrough antagonist performances came in Sudden Fear (1952), where Palance portrayed Lester Blaine, a duplicitous actor who marries and plots to murder composer Joan Crawford for her wealth, earning his first Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor.[38] This was followed by his iconic role as Jack Wilson, the sadistic gunslinger in Shane (1953), who terrorizes settlers and duels the titular hero, securing a second Oscar nomination despite limited screen time of under 13 minutes.[38][37] Subsequent parts reinforced the typecasting, including a renegade Apache warrior in Arrowhead (1953), the serial killer in Man in the Attic (1953) as Jack the Ripper, and the barbaric Attila the Hun in Sign of the Pagan (1954).[38] Palance attributed his authentic menace to mining hardships, remarking that they taught him "to hate," which he channeled into roles where the villain served as the story's emotional core, arguing that inspiring audience revulsion yielded greater rewards than heroic portrayals.[37]Challenges with Hollywood Establishment

Palance cultivated a reputation for intensity and confrontational behavior that strained relations with colleagues and potentially limited his standing within Hollywood's studio-dominated hierarchy of the 1950s. Eyewitness accounts described him as quick-tempered on sets, where he intimidated co-actors, contributing to perceptions of unreliability among producers who prioritized controllable talent.[39] This dynamic contrasted with the era's preference for actors amenable to studio oversight, as evidenced by Palance's own reflections on the industry's rigid expectations for leading men, which his rugged persona and unyielding demeanor defied.[18] A notable incident underscoring these tensions occurred during the 1966 production of The Professionals, when Palance punched co-star Burt Lancaster in the face amid a dispute, reinforcing his image as combative and exacerbating reluctance from executives to cast him in high-profile collaborative projects.[18] Similarly, Richard Widmark, who worked with Palance on Panic in the Streets (1950), characterized him as "very intense," highlighting how such traits, while fueling compelling performances, alienated peers in an industry reliant on harmonious ensembles.[39] These episodes, coupled with Palance's refusal to soften his approach for commercial appeal, likely contributed to sporadic unemployment even after Academy Award nominations for Sudden Fear (1952) and Shane (1953), as studios favored more pliable alternatives.[40] Palance's challenges extended beyond interpersonal clashes to a broader incompatibility with Hollywood's conformity-driven culture, where independent-minded performers risked marginalization. Unlike contemporaries who navigated the system through diplomacy, Palance's straightforward critiques of typecasting and role limitations—expressed in interviews—signaled resistance to executive dictates, prompting him to pursue opportunities outside major U.S. productions by the late 1950s.[18] This friction, rooted in causal mismatches between his authentic intensity and the establishment's demand for marketable predictability, underscored the era's barriers to actors unwilling to fully assimilate.[41]International and Diverse Work

European Film Ventures

In the early 1960s, Jack Palance sought opportunities in European cinema amid limited Hollywood roles, starring in several low-budget historical epics and adventure films produced primarily in France and Italy. These productions capitalized on the Italian peplum genre's popularity, featuring muscular heroes in ancient settings, though Palance's intense persona often suited antagonistic or authoritative figures.[5] Palance's European phase began with the French-Italian co-production Austerlitz (released December 1960), directed by Abel Gance, where he portrayed Austrian General Weirother in a dramatization of Napoleon's 1805 victory.[42] He followed with Revak the Rebel (1960), filmed on location in Italy, playing the titular Iberian prince Revak who leads a revolt against Carthaginian oppressors during the Second Punic War; the film, budgeted at $750,000 by NBC, exemplified cross-Atlantic financing for spectacle-driven narratives.[43] In 1961, Palance appeared in multiple Italian films, including Sword of the Conqueror, a tale of Lombard conquests; The Mongols, directed in part by André De Toth, as a Mongol warlord alongside Anita Ekberg; and the ensemble satire The Last Judgment under Vittorio De Sica.[44][45] A highlight was Barabbas (1961), an international epic filmed extensively in Italy—including Rome, Verona, and the sulfur mines of Mount Etna in Sicily—where Palance played the brutal gladiator Rufio, mentoring the protagonist in arena combat.[46] These ventures provided prolific output but were generally regarded as formulaic genre fare rather than artistic achievements, sustaining Palance's career through action-oriented roles abroad.[47]Italian Spaghetti Westerns

In the late 1960s, as opportunities in Hollywood waned due to typecasting and industry shifts, Jack Palance turned to European productions, including several Italian Spaghetti Westerns that capitalized on the genre's demand for American actors with intimidating physiques and gravelly voices. These low-budget films, typically shot in Spain with Italian financing and direction, featured heightened violence, moral ambiguity, and stylized gunplay, often set against historical backdrops like the Mexican Revolution. Palance's roles in this subgenre, spanning 1968 to 1972, showcased his versatility from outright villains to reluctant anti-heroes, drawing on his earlier success as a heavy in American Westerns like Shane (1953).[48] Palance's entry into Spaghetti Westerns came with The Mercenary (Il mercenario, 1968), directed by Sergio Corbucci, where he played Curly (Ricciolo), a prissy yet ruthless American gambler and killer who betrays allies and pursues revenge amid revolutionary chaos. Co-starring Franco Nero as the Polish mercenary Yodlaf, the film pitted Palance's character against a coalition of revolutionaries and soldiers, emphasizing his snarling menace and sudden brutality, including a scene where he murders his own partner. Released in December 1968, it exemplified the genre's blend of cynicism and explosive action, with Palance's performance adding a layer of unhinged unpredictability to the ensemble.[49][50] He reprised collaboration with Corbucci and Nero in Compañeros (Vamos a matar, compañeros, 1970), portraying John, a psychopathic mercenary and former associate of the protagonist, characterized by drug addiction, a mechanical hook hand, and explosive rage. As the film's chief antagonist, Palance's John schemes to seize a cache of weapons during a proxy conflict involving revolutionaries and CIA interests, delivering a portrayal of deranged intensity that included hallucinatory sequences and brutal confrontations. The movie, scored by Ennio Morricone, highlighted Palance's ability to embody eccentric evil, contributing to its status as a genre staple.[51] Later entries included It Can Be Done Amigo (Si può fare... amigo, 1972), directed by Giorgio Gentili, in which Palance assumed a more sympathetic lead as Sonny Bronston, a gunslinger escorting a widow and her son while evading bandits and a relentless sheriff. This shift to a heroic archetype demonstrated his range beyond villainy, though the film's lighter tone and comedic elements underscored the genre's evolution toward parody. Palance's Spaghetti Western phase, yielding at least four credited titles by 1972, sustained his career through international markets, where his craggy features and authoritative presence resonated with audiences seeking gritty authenticity over polished stars.[52]Return to American Productions

Following his engagements in European cinema, particularly Italian spaghetti westerns such as Compañeros (1970), Palance resumed work in American productions with the Western Monte Walsh (1970), directed by William A. Fraker in his feature debut.[53] In the film, Palance portrayed Chet Rollins, a steadfast cowboy grappling with the decline of the frontier era alongside Lee Marvin's title character, emphasizing themes of obsolescence and loyalty amid encroaching modernization.[54] The production, filmed primarily in Alberta, Canada, marked a return to rugged American Western archetypes that had defined Palance's earlier career.[53] Palance continued this trajectory with Oklahoma Crude (1973), a comedy-drama Western directed by Stanley Kramer, where he played the antagonist Noble "Shorty" Lee, a ruthless enforcer dispatched to seize an independent oil derrick from Faye Dunaway's character in 1910s Oklahoma.[55] The film, blending action with satirical elements on resource exploitation, showcased Palance's signature menacing presence against George C. Scott's drifter ally.[56] Shot partly in Spain but produced by American studio Columbia Pictures, it highlighted Palance's versatility in period industrial conflict narratives.[55] In 1974, Palance starred as Count Dracula in the CBS television movie Bram Stoker's Dracula, directed by Dan Curtis and adapted by Richard Matheson, portraying the vampire count as a brooding, vengeful figure seeking reincarnation through a resemblance to his lost wife.[57] This American production, emphasizing horror and gothic romance over camp, drew on Palance's intense physicality for a more feral interpretation than prior screen Draculas, though it aired as a made-for-TV feature rather than theatrical release.[57] The decade's American output concluded prominently with The Four Deuces (1975), a Prohibition-era gangster comedy directed by William H. Bushnell, in which Palance led as Vic Morono, a casino-owning mob boss defending his bootlegging empire amid rival threats.[58] Produced independently in the U.S., the film leaned into tongue-in-cheek melodrama, with Palance's authoritative menace anchoring the ensemble including Carol Lynley.[59] These roles signaled Palance's reintegration into domestic filmmaking, often as authoritative figures in genre pieces, bridging his international phase back to Hollywood-adjacent projects before further television emphasis.Television Contributions

Hosting Ripley's Believe It or Not!

Jack Palance served as the primary host for the ABC network revival of the documentary television series Ripley's Believe It or Not!, which ran weekly from September 26, 1982, to 1986, producing 76 episodes across four seasons.[60][61] The program documented bizarre natural phenomena, unusual human feats, historical oddities, and artistic eccentricities inspired by Robert L. Ripley's original syndicated newspaper panel, with Palance frequently providing on-location narration in locations worldwide to introduce segments on improbable events and curiosities.[60][62] The series was preceded by a pilot special directed by Ronald Lyon, featuring Palance as host and serving as a forerunner that highlighted strange facts and artifacts, which aired in 1981.[63] Co-hosts assisted Palance in presenting material, varying by season: Catherine Shirriff appeared alongside him in season 1, his daughter Holly Palance co-hosted seasons 2 and 3, and Marie Osmond took the role in season 4.[64] Episodes typically combined studio segments with field reports, emphasizing verifiable yet astonishing claims, such as extreme physical stunts or rare artifacts, often verified through Ripley's archives or on-site investigations.[65] Palance's gravelly delivery and imposing presence lent a sense of gravitas to the often whimsical content, contributing to the show's appeal as an alternative to standard news programming in the early 1980s.[60] User reviews on IMDb rate the series at 7.7 out of 10 based on 561 votes, praising its engaging format and Palance's authoritative style in unveiling the extraordinary.[60] The hosting role marked a significant television commitment for Palance during a period of career transition, sustaining his visibility between film projects.[60]Guest and Supporting TV Roles

Palance earned early television recognition for his portrayal of the washed-up heavyweight boxer Mountain Rivera in the October 11, 1956, episode "Requiem for a Heavyweight" on the anthology series Playhouse 90. Directed by Ralph Nelson and written by Rod Serling, the live broadcast depicted Rivera's struggle with career-ending injuries and exploitation by his manager, co-starring Ed Wynn as the sympathetic manager Maish and Keenan Wynn as the trainer Army. Palance's performance, marked by physical vulnerability contrasting his typical tough-guy persona, won him the Primetime Emmy Award for Best Single Performance by an Actor.[66][67] In the late 1960s, Palance took on dual roles as Dr. Henry Jekyll and Mr. Edward Hyde in the 1968 made-for-television film The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, adapting Robert Louis Stevenson's novella with emphasis on the character's descent into moral corruption. He continued with guest appearances in episodic television, including the two-part The Man from U.N.C.L.E. storyline "The Concrete Overcoat Affair" (1967–1968), where he played the menacing Louis Striga, a Thrush operative involved in mind-control experiments.[30][31] Palance starred as the titular vampire in the 1974 CBS television movie Dracula, directed by Dan Curtis and adapted from Bram Stoker's novel by Richard Matheson, portraying the count's obsessive pursuit of a reincarnation of his lost love amid gothic horror elements in England. The production featured Simon Ward as Arthur Holmwood and Nigel Davenport as Van Helsing, with Palance's interpretation emphasizing raw ferocity over seduction.[57]Career Revival and Peak Recognition

1980s and 1990s Resurgence

In the late 1980s, Palance secured prominent antagonist roles in major Hollywood productions, signaling a revival in his feature film presence after decades of varied supporting work. In Young Guns (1988), directed by Christopher Cain, he portrayed L.G. Murphy, a ruthless cattle baron and key adversary to the film's young protagonists in this Western depicting the Lincoln County War.[68] The film, starring Emilio Estevez, Kiefer Sutherland, and Lou Diamond Phillips, grossed over $45 million domestically and highlighted Palance's enduring ability to embody menacing authority figures. This momentum continued with back-to-back appearances in 1989 action blockbusters. In Tango & Cash, directed by Andrei Konchalovsky, Palance played Yves Perret, a sophisticated yet sadistic crime lord orchestrating the framing of protagonists Sylvester Stallone and Kurt Russell for murder.[69] The film earned approximately $37 million in North America despite mixed reviews, capitalizing on Palance's portrayal of a calculating villain who fondles pet mice as a quirky trait. Later that year, in Tim Burton's Batman, he depicted Carl Grissom, an aging Gotham mob boss whose empire unravels amid betrayals involving Jack Nicholson's Joker.[70] Palance's performance as the gravel-voiced, wheelchair-bound Grissom added depth to the film's criminal underworld, contributing to Batman's global box office haul exceeding $411 million. These roles, emphasizing Palance's gravelly voice, imposing physique, and capacity for understated menace, reinvigorated his Hollywood visibility following earlier B-grade horror and exploitation fare like Hawk the Slayer (1980) and Alone in the Dark (1982).[32] Into the early 1990s, he maintained momentum with parts in science fiction outings such as Solar Crisis (1990), where he appeared as a supporting character in a disaster-themed ensemble, underscoring his versatility amid high-concept productions before peaking with comedic turns.[30] This phase solidified Palance as a go-to actor for authoritative villains in mainstream cinema, bridging his 1950s typecasting with late-career acclaim.City Slickers and Supporting Oscar Win

In the 1991 comedy City Slickers, directed by Ron Underwood and starring Billy Crystal as Mitch Robbins, Jack Palance portrayed Curly Washburn, the enigmatic and intimidating trail boss leading a group of urban vacationers on a cattle drive from New Mexico to Colorado.[71] Palance's character, a weathered cowboy dispensing terse wisdom on life and self-reliance, appeared in roughly 15 minutes of screen time but dominated the film's emotional core through scenes like the "secret of life" monologue, where Curly tells Mitch, "One thing. Just one thing," emphasizing singular focus amid midlife crises.[72] The role drew on Palance's established screen persona as a rugged antagonist, blending menace with unexpected depth, which critics noted revitalized his image beyond Western villains.[73] Palance was Billy Crystal's initial choice for Curly, but he initially declined due to scheduling conflicts with another project; Crystal then offered the part to Charles Bronson, who rejected it reportedly because the character dies midway through the film.[74] Palance ultimately accepted after becoming available, improvising elements like knife-throwing and horse-handling to enhance Curly's authenticity, informed by his own Pennsylvania ranch experience and physical fitness regimen.[75] His preparation included minimal rehearsal with Crystal to preserve Curly's aloof mystique, resulting in palpable on-screen tension that underscored themes of mentorship and mortality.[74] The film's box office success—grossing over $247 million worldwide on a $23 million budget—amplified Palance's visibility, though it received only one Oscar nomination.[71] On March 30, 1992, at the 64th Academy Awards held at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Palance won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for City Slickers, defeating nominees including Tommy Lee Jones (JFK), Harvey Keitel (Bugsy), Ben Kingsley (Bugsy), and Michael Lerner (Barton Fink).[76] At age 73, he was the oldest winner in the category at the time, marking his first Academy Award after nominations for Sudden Fear (1952) and Shane (1953).[77] Presented by Whoopi Goldberg, Palance's acceptance speech famously culminated in three one-armed push-ups on stage, a spontaneous demonstration of vitality to counter perceptions of him as a Hollywood has-been reliant on stunt doubles.[78] He quipped about the industry mistaking his age for frailty, stating, "I can do it, too," which drew applause and became one of the ceremony's most iconic moments.[79] The win, paired with a Golden Globe for the same role, propelled Palance into a late-career renaissance, leading to a sequel, City Slickers II: The Legend of Curly's Gold (1994), where he reprised Curly as a ghostly figure.[80] Critics attributed the Oscar to Palance's economical intensity—described by reviewers as "scene-stealing" and transformative for a comedy—rather than the film's overall merits, highlighting how his gravelly delivery and physicality conveyed Curly's philosophy of unadorned existence.[81] This accolade affirmed Palance's enduring appeal, bridging his 1950s tough-guy archetype with 1990s comedic gravitas, though some contemporaries viewed the award as compensatory for prior oversights in recognizing his dramatic range.[73]Final Film and Stage Appearances

Palance's late-career output shifted toward television movies and direct-to-video productions, reflecting a decline in major theatrical releases following his Oscar-winning role in City Slickers (1991). In 1998, he portrayed Ebenezer Scrooge in Ebenezer, a Western adaptation of Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol directed by Peter H. Hunt, where the miserly character navigates redemption amid frontier outlaws and spectral visitations.[82] This Hallmark Entertainment production emphasized Palance's gravelly authority in a familiar narrative, airing on TNT. The following year, Palance took on the iconic pirate Long John Silver in the Hallmark Channel's Treasure Island (1999), adapted from Robert Louis Stevenson's novel and directed by Peter Rowe. Filmed in South Africa, the project featured Palance as the cunning, one-legged buccaneer manipulating young Jim Hawkins (Kevin Zegers) during a quest for buried gold, marking a return to swashbuckling villainy that echoed his early menacing personas.[30] Critics noted Palance's physicality and intensity, though the film's budget constraints limited its scope compared to earlier adaptations. Palance continued with family-oriented telefilms into the early 2000s. In Sarah, Plain and Tall: Winter's End (2000), a CBS production concluding the series based on Patricia MacLachlan's books, he played John Witting, the widowed prairie farmer reuniting with his children during a harsh winter, opposite Glenn Close as Sarah.[82] This role highlighted a softer, paternal side, contrasting his typical tough-guy archetypes. His final screen appearance came in Prancer Returns (2001), a sequel to the 1989 holiday film, where Palance reprised a grumpy but ultimately benevolent farmer aiding a girl and her reindeer in rural America; directed by Joshua Miller, it premiered on cable without theatrical release.[82] No significant stage appearances are recorded in Palance's final years, with his theatrical focus having waned after early Broadway successes like understudying Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) and starring in The Big Two (1947).[23] Post-2001, health issues curtailed further professional engagements until his death in 2006.[30]Personal Life

Marriages, Family, and Children

Palance married actress Virginia Baker on April 21, 1949; the union produced three children and ended in divorce in 1969.[83] The couple's daughters, Holly Palance (born 1950) and Brooke Palance (born 1952), both entered the acting profession, with Holly appearing in films such as The Omen (1976) and Brooke in productions like The Four Deuces (1975).[17] Their son, Cody Palance (born December 1955), also acted in roles including Young Guns (1988) but died of malignant melanoma on July 15, 1998, in Tijuana, Mexico, at age 42.[84][85] Palance's second marriage, to Elaine Rogers on May 6, 1987, likewise concluded in divorce prior to his death, though some contemporary reports referred to her as his widow; no children were born from this marriage.[84][83] Brooke Palance later married Michael Wilding Jr., son of actress Elizabeth Taylor, while Holly wed film director Roger Spottiswoode, with whom she had two children.[17] Virginia Baker was killed by a car in Los Angeles on January 1, 2003.[86]Residences, Hobbies, and Lifestyle

Palance maintained multiple residences reflecting his roots and professional life in entertainment. In the 1950s, he owned a Coldwater Canyon estate in Beverly Hills, California, built in 1940, which he purchased during his rising Hollywood career.[87] Later, he resided at 1005 Hartford Way in Beverly Hills, a property noted for its historic significance.[88] In his later years, Palance favored rural properties, including a 1,000-acre cattle ranch named Holly Brooke Ranch in Cummings Valley near Tehachapi, California, which featured his custom ranch brand incorporating the initials of his children—Holly, Brooke, and Cody—and sold for approximately $6.5 million after his death.[89][73] He also owned a 500-acre farm off St. John's Road in Butler Township, Pennsylvania, where he returned annually in summer, maintaining ties to his coal-mining heritage in the region.[90][91] Beyond acting, Palance pursued painting as a serious avocation, producing original acrylic works in an Americana style that were exhibited and sold posthumously from his widow's private collection.[92][93] His artwork, often thematic and spring-inspired, reflected a creative outlet separate from his screen persona, with pieces auctioned for values starting at $15.[94] Palance embodied a rugged, fitness-oriented lifestyle aligned with his on-screen tough-guy roles, emphasizing physical discipline into advanced age. At 84, he demonstrated one-armed push-ups onstage during public appearances, including at the 2004 Festival of the West in Scottsdale, Arizona, to engage fans and affirm his vitality.[95] His routine involved ranch work on his California property near Stallion Springs, which he described as one of his favorite places, combining equestrian activities with self-reliant living.[96] This hands-on approach extended to Pennsylvania summers, where farm maintenance reinforced his preference for active, outdoor pursuits over urban sedentary habits.[97]Public Persona and Temperament

Jack Palance's public persona was defined by an aura of quiet menace and rugged intensity, shaped by his physical attributes—including a height of 6 feet 4 inches, sharp cheekbones, piercing eyes, and gravelly voice—that lent authenticity to his frequent portrayals of villains and tough antagonists in film.[98][18] This image extended beyond the screen, as he was often perceived in Hollywood as an embodiment of the hard-edged characters he played, such as sociopathic gunfighters or murderous figures, parodying his own tough-guy archetype in later roles like Curly in City Slickers (1991).[99][100] Off-screen, Palance's temperament contrasted sharply with his public image; contemporaries described him as mild-spoken, thoughtful, and a devoted family man, having evolved from an earlier arrogant demeanor rooted in his coal-mining upbringing to a more reflective disposition by the 1950s.[37] He maintained interests in watercolor painting, poetry, and storytelling, while adhering to a vegetarian diet and sobriety, revealing a shy and principled side beneath the intimidating exterior.[18] Despite this, he possessed a quick temper on set, reportedly intimidating fellow actors through displays of intensity, as noted by eyewitness accounts from co-stars like Richard Widmark.[39] Palance expressed disdain for sensationalized media portrayals of himself, once remarking, "I'm amazed people read this crap about us—about me most of all," underscoring his straightforward, unpretentious nature that aligned with his gruff humor yet prioritized personal integrity over Hollywood pretense.[101] Colleagues and family affirmed his gentle off-screen character, emphasizing a legacy of quiet generosity and depth that defied simplistic tough-guy stereotypes.[102]Death and Legacy

Health Decline and Death

In his later years, Jack Palance suffered from failing health amid multiple maladies associated with advanced age.[73] This period was further compounded by the 1998 death of his son Cody from melanoma, which deeply affected him emotionally.[1] Palance was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer prior to his passing.[1][103] Palance died on November 10, 2006, at the age of 87, at his daughter Holly Palance's home in Montecito, Santa Barbara County, California, surrounded by family members.[104][73] His spokesman, Dick Guttman, reported the cause as natural causes, though consistent accounts attribute it to complications from pancreatic cancer.[105][103]Cultural Impact and Critical Reception

Jack Palance's portrayals of villains and tough characters earned him acclaim for his intense, menacing screen presence, characterized by a gravelly voice and angular features that conveyed palpable threat. Critics highlighted his ability to embody feral antagonism, as in his Oscar-nominated role as the psychopathic husband in Sudden Fear (1952), where he terrorized Joan Crawford, and as the gunslinger Jack Wilson in Shane (1953), opposite Alan Ladd, for which he received another Academy Award nomination.[106][5] His performance in City Slickers (1991) as the grizzled cowboy Curly Washburn culminated in a Best Supporting Actor Oscar win, with reviewers praising the blend of humor and authenticity that subverted his earlier typecasting.[6] Palance's cultural footprint endures through memorable archetypes and public moments that transcended his films. His snarling villainy in Westerns like Shane solidified the image of the ruthless gunslinger in American cinema, influencing subsequent portrayals of moral ambiguity in the genre.[107] The 1992 Academy Awards ceremony amplified his legacy when, at age 73, he performed three one-armed push-ups onstage during his acceptance speech for City Slickers, demonstrating physical vigor and injecting irreverent energy into the event; host Billy Crystal subsequently parodied the stunt throughout the broadcast, embedding it in pop culture as a symbol of defiant machismo.[76] This moment, viewed by millions, contrasted his onscreen ferocity with offscreen vitality, fostering enduring memes and references in media.[78] Critics occasionally noted Palance's challenges in diversifying beyond heavies, attributing his career longevity to raw intensity rather than range, though he demonstrated versatility in television adaptations like Requiem for a Heavyweight (1956) and international fare such as Le Mépris (1963).[6] His Ukrainian heritage, reflected in visits to his ancestral homeland and cultural advocacy, added depth to his public image, though mainstream reception focused more on his Hollywood persona than ethnic contributions.[37] Overall, Palance's work impacted perceptions of villainy as psychologically compelling rather than cartoonish, with his Oscar triumph affirming late-career relevance amid a landscape favoring younger stars.[5]Achievements, Criticisms, and Controversies

Palance earned two Academy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actor in the early 1950s, for his roles as the menacing husband in Sudden Fear (1952) and the gunslinger Jack Wilson in Shane (1953).[108] Nearly four decades later, he won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for portraying the tough rancher Curly Washburn in City Slickers (1991), receiving the honor at the 64th Academy Awards ceremony on March 30, 1992.[78] For the same performance, he secured a Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture.[109] Other accolades included a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role for the television production Requiem for a Heavyweight on Playhouse 90 in 1957, as well as a Bronze Wrangler from the Western Heritage Awards in 1993 for Legends of the West (1992) and a Lifetime Achievement Award from WorldFest Flagstaff in 1998.[110][108] Critics occasionally faulted Palance's intense, stylized acting as overly theatrical or mannered, particularly in villainous roles that emphasized his physicality and gravelly voice over subtle nuance, though this approach often amplified his memorability in genres like Westerns and film noir.[18] On set, he cultivated a reputation for abrasiveness, including punching co-star Burt Lancaster during a 1966 confrontation while filming The Professionals, reportedly over a disagreement about a scene's execution.[18] Similar tensions arose with Richard Widmark during Panic in the Streets (1950), where a scripted pistol-whipping sequence escalated into real friction.[111] Palance publicly derided many directors he worked with, asserting that most "shouldn't even be directing traffic," which contributed to perceptions of him as uncooperative in Hollywood's collaborative environment. Controversies surrounding Palance were limited but tied to his combative persona and shifting politics. Tabloid outlet Confidential magazine alleged in the 1950s that he assaulted a woman during an early career incident, claiming he shook her violently before assaulting her, though such reports from sensationalist publications lacked corroboration and reflected era-specific smear tactics against rising stars.[112] His evolution from early liberal leanings to outspoken conservatism, including support for figures like Ronald Reagan, irked Hollywood's dominant left-leaning culture and fueled rumors of industry ostracism, with some attributing dry spells in his career to this stance rather than typecasting.[40][113] At the 1992 Oscars, his acceptance speech—punctuated by one-arm push-ups to honor his stuntman brother and mock ageism—drew mixed reactions, with some viewing it as defiant showmanship and others as disruptive antics amid the ceremony's formality.[114]Professional Output

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Panic in the Streets | Blackie |

| 1950 | Halls of Montezuma | Boxing Marine |

| 1952 | Sudden Fear | Carey |

| 1953 | Shane | Jack Wilson[115] |

| 1953 | Second Chance | Cobby |

| 1953 | Flight to Tangier | Scorch |

| 1953 | Arrowhead | Chief Chattez |

| 1953 | Man in the Attic | Willie Killer |

| 1954 | Sign of the Pagan | Attila the Hun |

| 1954 | The Silver Chalice | Chogal |

| 1955 | The Big Knife | Buddy Bliss |

| 1955 | I Died a Thousand Times | Roy Earle |

| 1956 | Attack | Lt. Joe Costa |