Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Polycythemia

View on Wikipedia| Polycythemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Erythrocytosis, Hypercythemia, Hypererythrocythemia |

| |

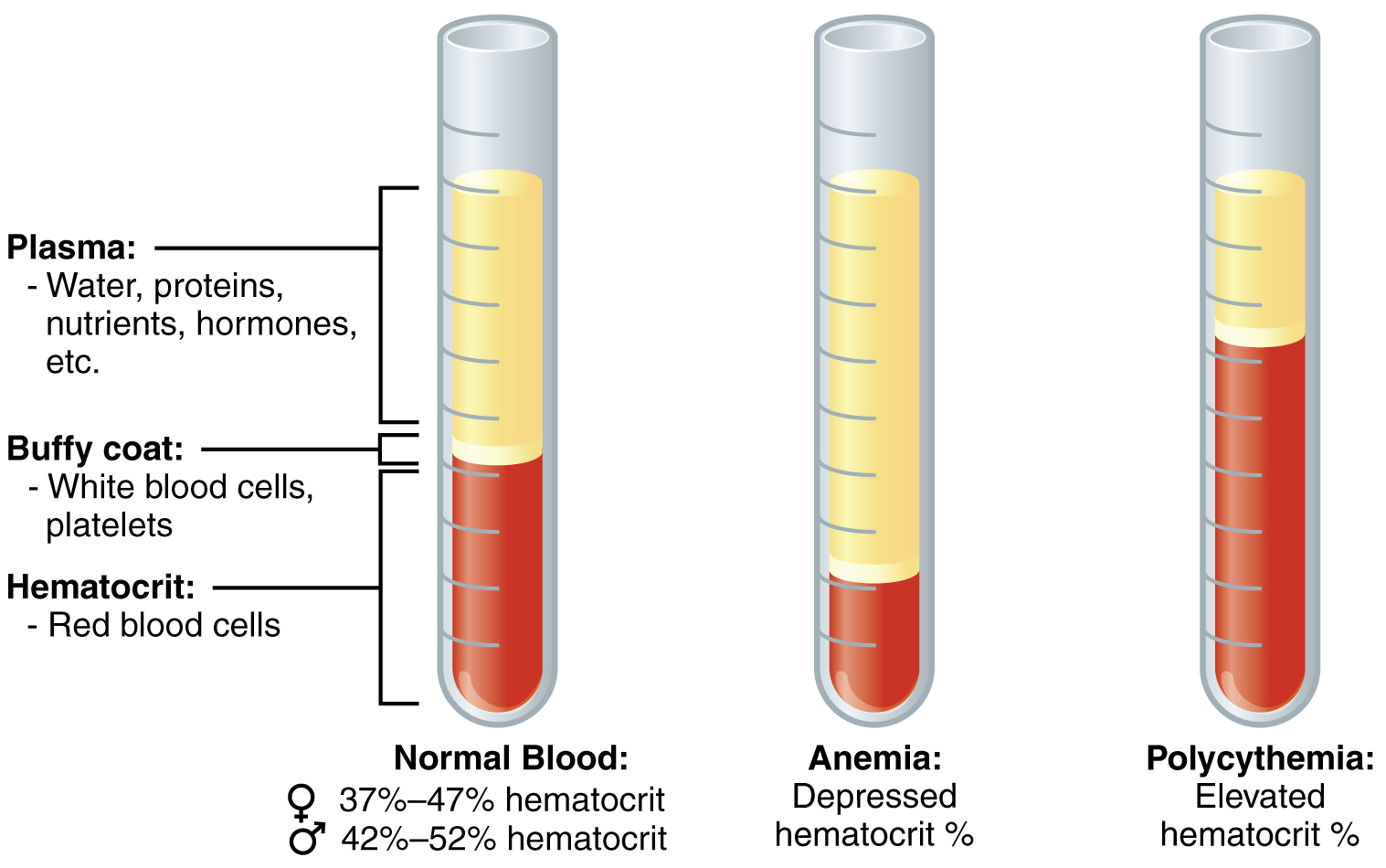

| Diagram illustrating normal composition of blood compared to anemia and polycythemia | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

Polycythemia (also spelt polycythaemia) is a laboratory finding that the hematocrit (the volume percentage of red blood cells in the blood) and/or hemoglobin concentration are increased in the blood. Polycythemia is sometimes called erythrocytosis, and there is significant overlap in the two findings, but the terms are not the same: polycythemia describes any increase in hematocrit and/or hemoglobin, while erythrocytosis describes an increase specifically in the number of red blood cells in the blood.[citation needed]

Polycythemia has many causes. It can describe an increase in the number of red blood cells[1] ("absolute polycythemia") or a decrease in the volume of plasma ("relative polycythemia").[2] Absolute polycythemia can be due to genetic mutations in the bone marrow ("primary polycythemia"), physiological adaptations to one's environment, medications, and/or other health conditions.[3][4] Laboratory studies such as serum erythropoeitin levels and genetic testing might be helpful to clarify the cause of polycythemia if the physical exam and patient history do not reveal a likely cause.[5]

Mild polycythemia on its own is often asymptomatic. Treatment for polycythemia varies, and typically involves treating its underlying cause.[6] Treatment of primary polycythemia (see polycythemia vera) could involve phlebotomy, antiplatelet therapy to reduce risk of blood clots, and additional cytoreductive therapy to reduce the number of red blood cells produced in the bone marrow.[7]

Definition

[edit]Polycythemia is defined as serum hematocrit (Hct) or hemoglobin (HgB) exceeding normal ranges expected for age and gender, typically Hct >49% in healthy adult men and >48% in women, or HgB >16.5 g/dL in men or >16.0 g/dL in women.[8] The definition is different for neonates and varies by age in children.[9][10]

Differential diagnoses

[edit]Polycythemia in adults

[edit]Different diseases or conditions can cause polycythemia in adults. These processes are discussed in more detail in their respective sections below.

Relative polycythemia, also known as pseudopolycythemia,[11] is not a true increase in the number of red blood cells or hemoglobin in the blood, but rather an elevated laboratory finding caused by reduced blood plasma (hypovolemia, cf. dehydration). Relative polycythemia is often caused by loss of body fluids, such as through burns, dehydration, and stress.[citation needed] A specific type of relative polycythemia is Gaisböck syndrome; in this syndrome, primarily occurring in obese men, hypertension causes a reduction in plasma volume, resulting in (amongst other changes) a relative increase in red blood cell count.[12] If relative polycythemia is deemed unlikely because the patient has no other signs of hemoconcentration and has sustained polycythemia without clear loss of body fluids, the patient likely has absolute or true polycythemia.

Absolute or true polycythemia (also erythrocytosis) can be split into two categories:

- Primary polycythemia, that is the overproduction of red blood cells due to a primary process in the bone marrow (a so-called myeloproliferative disease; eg. polycythemia vera). These can be familial or congenital, or acquired later in life.[13]

- Secondary polycythemia, whenever additional red blood cells may have been received through another process — for example, being over-transfused (either accidentally or, as blood doping, deliberately).[citation needed]

Polycythemia in neonates

[edit]Polycythemia in newborns is defined as hematocrit > 65%. Significant polycythemia can be associated with blood hyperviscosity, or thickening of the blood. Causes of neonatal polycythemia include:

- Hypoxia: Poor oxygen delivery (hypoxia) in utero resulting in compensatory increased production of red blood cells (erythropoeisis). Hypoxia can be either acute or chronic. Acute hypoxia can occur as a result of perinatal complications. Chronic fetal hypoxia is associated with maternal risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and smoking.[10]

- Umbilical cord stripping: delayed cord clamping and the stripping of the umbilical cord towards the baby can cause the residual blood in the cord/placenta to enter fetal circulation, which can increase blood volume.[10]

- The recipient twin in a pregnancy undergoing twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome can have polycythemia.[14]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The pathophysiology of polycythemia varies based on its cause. The production of red blood cells (or erythropoeisis) in the body is regulated by erythropoietin, which is a protein produced by the kidneys in response to poor oxygen delivery.[15] As a result, more erythropoietin is produced to encourage red blood cell production and increase oxygen-carrying capacity. This results in secondary polycythemia, which can be an appropriate response to hypoxic conditions such as chronic smoking, obstructive sleep apnea, and high altitude.[4] Furthermore, certain genetic conditions can impair the body's accurate detection of oxygen levels in the serum, which leads to excess erythropoietin production even without hypoxia or impaired oxygen delivery to tissues.[16][17] Alternatively, certain types of cancers, most notably renal cell carcinoma, and medications such as testosterone use can cause inappropriate erythropoietin production that stimulates red cell production despite adequate oxygen delivery.[18]

Primary polycythemia, on the other hand, is caused by genetic mutations or defects of the red cell progenitors within the bone marrow, leading to overgrowth and hyperproliferation of red blood cells regardless of erythropoeitin levels.[3]

Increased hematocrit and red cell mass with polycythemia increases the viscosity of blood, leading to impaired blood flow and contributing to an increased risk of clotting (thrombosis).[19]

Evaluation

[edit]History and physical exam

[edit]The first step to evaluate new polycythemia in any individual is to conduct a detailed history and physical exam.[13] Patients should be asked about smoking history, altitude, medication use, personal bleeding and clotting history, symptoms of sleep apnea (snoring, apneic episodes), and any family history of hematologic conditions or polycythemia. A thorough cardiopulmonary exam including auscultation of the heart and lungs can help evaluate for cardiac shunting or chronic pulmonary disease. An abdominal exam can assess for splenomegaly, which can be seen in polycythemia vera. Examination of digits for erythromelalgia, clubbing or cyanosis can help assess for chronic hypoxia.[13]

Laboratory evaluation

[edit]Polycythemia is often initially identified on a complete blood count (CBC). The CBC is often repeated to evaluate for persistent polycythemia.[13] If an etiology of polycythemia is unclear from history or physical, additional laboratory evaluation might include:[5]

- Blood smear to evaluate cell morphology[7]

- Iron panel to evaluate for concurrent iron deficiency

- JAK2 mutation testing[13]

- Serum erythropoeitin (EPO) levels[5]

- Oxygen saturation (usually via pulse oximetry or blood gas tests) or oxygen dissociation tests[13]

Additional testing

[edit]- Sleep studies if high suspicion for sleep apnea[13]

- Abdominal imaging, such as ultrasound[5]

- Erythropoietin receptor or von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) genetic testing, if high suspicion for familial erythrocytosis[5]

- Hemoglobin (globin-gene) sequencing or high-performance liquid chromatography to evaluate for high-affinity hemoglobin variants[13]

- Bone marrow biopsy might be considered in specific cases[5]

Polycythemia types

[edit]Primary polycythemia

[edit]Primary polycythemias are myeloproliferative diseases affecting red blood cell precursors in the bone marrow. Polycythemia vera (PCV) (a.k.a. polycythemia rubra vera (PRV)) occurs when excess red blood cells are produced as a result of an abnormality of the bone marrow.[3] Often, excess white blood cells and platelets are also produced. A hallmark of polycythemia vera is an elevated hematocrit, with Hct > 55% seen in 83% of cases.[20] A somatic (non-hereditary) mutation (V617F) in the JAK2 gene, also present in other myeloproliferative disorders, is found in 95% of cases.[21] Symptoms include headaches and vertigo, and signs on physical examination include an abnormally enlarged spleen and/or liver. Studies suggest that mean arterial pressure (MAP) only increases when hematocrit levels are 20% over baseline. When hematocrit levels are lower than that percentage, the MAP decreases in response, which may be due, in part, to the increase in viscosity and the decrease in plasma layer width.[22] Furthermore, affected individuals may have other associated conditions alongside high blood pressure, including formation of blood clots. Transformation to acute leukemia is rare. Phlebotomy is the mainstay of treatment.[23]

Primary familial polycythemia, also known as primary familial and congenital polycythemia (PFCP), exists as a benign hereditary condition, in contrast with the myeloproliferative changes associated with acquired PCV. In many families, PFCP is due to an autosomal dominant mutation in the EPOR erythropoietin receptor gene.[24] PFCP can cause an increase of up to 50% in the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood; skier Eero Mäntyranta had PFCP, which is speculated to have given him an advantage in endurance events.[25]

Secondary polycythemia

[edit]Secondary polycythemia is caused by either natural or artificial increases in the production of erythropoietin, hence an increased production of erythrocytes.

Secondary polycythemia in which the production of erythropoietin increases appropriately is called physiologic polycythemia. Conditions which may result in physiologic polycythemia include:

- Altitude related – Polycythemia can be a normal adaptation to living at high altitudes (see altitude sickness).[9] Many athletes train at high altitude to take advantage of this effect, which can be considered a legal form of blood doping, although the efficacy of this strategy is unclear.[26]

- Hypoxic disease-associated – for example, in cyanotic heart disease where blood oxygen levels are reduced significantly; in hypoxic lung disease such as COPD; in chronic obstructive sleep apnea;[9] conditions that reduce blood flow to the kidney e.g. renal artery stenosis. Chronic carbon monoxide poisoning (which can be present in heavy smokers) and rarely methemoglobinemia can also impair oxygen delivery.[27][4]

- Genetic – Heritable causes of secondary polycythemia include abnormalities in hemoglobin oxygen release, which results in a greater inherent affinity for oxygen than normal adult hemoglobin and reduces oxygen delivery to tissues.[28]

Conditions where the secondary polycythemia is not caused by physiologic adaptation, and occurs irrespective of body needs include:[4]

- Neoplasms – Renal cell carcinoma, liver tumors, Von Hippel–Lindau disease, and endocrine abnormalities including pheochromocytoma and adrenal adenoma with Cushing's syndrome.

- Anabolic steroid use – people whose testosterone levels are high, including athletes who abuse steroids, people on testosterone replacement for hypogonadism or transgender hormone replacement therapy.[18]

- Blood doping – Athletes who take erythropoietin-stimulating agents or receive blood transfusions to increase their red blood cell mass.[29]

- Post-transplant erythrocytosis – About 10–15% of patients after renal transplantation are found to have polycythemia at 24 months after transplantation, which can be associated with increased thrombotic (clotting) risk.[30]

Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) and Secondary Polycythemia

Testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) causes secondary polycythemia by stimulating the body's natural pathways that regulate red blood cell production, rather than from an inherent bone marrow disorder. Testosterone increases the production of erythropoietin (EPO) in the kidneys, a hormone that signals the bone marrow to make more red blood cells. At the same time, testosterone suppresses the liver hormone hepcidin, which normally limits the absorption and mobilization of iron. With less hepcidin, iron becomes more available for hemoglobin synthesis, further fueling red blood cell production. This combination of increased EPO signaling and enhanced iron supply amplifies erythropoiesis, leading to elevated hematocrit and hemoglobin levels. The effect is most pronounced with injectable forms of testosterone that create high peak serum levels, which strongly stimulate these pathways. Because the mechanism is driven by a hormonal stimulus and not by a primary bone marrow abnormality, the condition is classified as secondary polycythemia. Clinically, this distinction is important, as TRT-induced secondary polycythemia resolves or improves with dose adjustment, delivery method changes, or therapeutic phlebotomy, whereas primary polycythemia reflects a chronic clonal disorder of hematopoietic stem cells.

Altered oxygen sensing

[edit]Rare inherited mutations in three genes which all result in increased stability of hypoxia-inducible factors, leading to increased erythropoietin production, have been shown to cause secondary polycythemia:

- Chuvash erythrocytosis or Chuvash polycythemia is an autosomal recessive form of erythrocytosis endemic in patients from the Chuvash Republic in Russia. Chuvash erythrocytosis is associated with homozygosity for a C598T mutation in the von Hippel–Lindau gene (VHL), which is needed for the destruction of hypoxia-inducible factors in the presence of oxygen.[17] Clusters of patients with Chuvash erythrocytosis have been found in other populations, such as on the Italian island of Ischia, located in the Bay of Naples.[16] Patients with Chuvash erythrocytosis experience a significantly elevated risk of events.[6]

- PHD2 erythrocytosis: Heterozygosity for loss-of-function mutations of the PHD2 gene are associated with autosomal dominant erythrocytosis and increased hypoxia-inducible factors activity.[31][32]

- HIF2α erythrocytosis: Gain-of-function mutations in HIF2α are associated with autosomal dominant erythrocytosis[33] and pulmonary hypertension.[34]

Symptoms

[edit]Polycythemia is often asymptomatic; patients may not experience any notable symptoms until their red cell count is very high. For patients with significant elevations in hemoglobin or hematocrit (often from polycythemia vera), some non-specific symptoms include:[9]

- A ruddy (red) complexion, or plethora[13]

- Headache, transient blurry vision (amaurosis fugax), other signs of a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke

- Dizziness, fatigue

- Unusual bleeding, nosebleeds

- Pain in abdomen from enlarged spleen in polycythemia vera

- Pain in hands and feet (erythromelalgia)

- Itchiness, especially after a hot shower (aquagenic pruritis)

- Numbness or tingling in different body parts[35]

Epidemiology

[edit]The prevalence of primary polycythemia (polycythemia vera) was estimated to be approximately 44–57 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.[30] Secondary polycythemia is considered to be more common, but its exact prevalence is unknown.[30] In one study using the NHANES dataset, the prevalence of unexplained erythrocytosis is 35.1 per 100,000, and was higher among males and among individuals between ages 50–59 and 60–69.[36]

Management

[edit]The management of polycythemia varies based on its etiology:

- See polycythemia vera for management of primary polycythemia, which involves reducing thrombotic risk, symptom amelioration and monitoring for further hematologic complications. Treatment can include phlebotomy, aspirin, and myelosuppressive or cytoreductive medications based on risk stratification.[7]

- For secondary polycythemia, management involves addressing the underlying etiology of increased erythropoeitin production, such as smoking cessation, CPAP for sleep apnea, or removing any EPO-producing tumours.[6] Phlebotomy is not typically recommended for patients with physiologic polycythemia, who rely on additional red cell mass for necessary oxygen delivery, unless the patient is clearly symptomatic and experiences relief from phlebotomy.[6] It is unclear if patients with secondary polycythemia are at elevated thrombotic risk, but aspirin can be considered for patients at elevated cardiovascular risk or for patients with Chuvash polycythemia.[6] The first-line treatment for post-transplant erythrocytosis specificity is angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers.[30]

Relation to athletic performance

[edit]Polycythemia is theorized to increased performance in endurance sports due to the blood being able to store more oxygen.[citation needed] This idea has led to the illegal use of blood doping and transfusions among professional athletes, as well as use of altitude training or elevation training masks to simulate a low-oxygen environment. However, the benefits of altitude training for athletes to improve sea-level performance are not universally accepted, with one reason being athletes at altitude might exert less power during training.[37]

See also

[edit]- Anemia, a decrease in red blood cell count

- Cytopenia, a decrease in blood cell count

- Capillary leak syndrome, another cause of hemoconcentration

References

[edit]- ^ "Absolute polycythemia" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ "Relative polycythemia" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ a b c MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Polycythemia vera

- ^ a b c d Mithoowani S, Laureano M, Crowther MA, Hillis CM (August 2020). "Investigation and management of erythrocytosis". CMAJ. 192 (32): E913 – E918. doi:10.1503/cmaj.191587. PMC 7829024. PMID 32778603.

- ^ a b c d e f McMullin MF, Bareford D, Campbell P, Green AR, Harrison C, Hunt B, et al. (July 2005). "Guidelines for the diagnosis, investigation and management of polycythaemia/erythrocytosis". British Journal of Haematology. 130 (2): 174–195. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05535.x. PMID 16029446. S2CID 11681060.

- ^ a b c d e Gangat N, Szuber N, Pardanani A, Tefferi A (August 2021). "JAK2 unmutated erythrocytosis: current diagnostic approach and therapeutic views". Leukemia. 35 (8): 2166–2181. doi:10.1038/s41375-021-01290-6. PMC 8324477. PMID 34021251.

- ^ a b c Spivak JL (July 2019). "How I treat polycythemia vera". Blood. 134 (4): 341–352. doi:10.1182/blood.2018834044. PMID 31151982.

- ^ Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. (May 2016). "The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia". Blood. 127 (20): 2391–2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. PMID 27069254. S2CID 18338178.

- ^ a b c d Pillai AA, Fazal S, Babiker HM (2022). "Polycythemia". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30252337. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- ^ a b c Sarkar S, Rosenkrantz TS (August 2008). "Neonatal polycythemia and hyperviscosity". Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 13 (4): 248–255. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2008.02.003. PMID 18424246.

- ^ Kaung, David T. (1962-10-01). ""Relative Polycythemia" or "Pseudopolycythemia"". Archives of Internal Medicine. 110 (4): 456. doi:10.1001/archinte.1962.03620220048008. ISSN 0003-9926.

- ^ Stefanini M, Urbas JV, Urbas JE (July 1978). "Gaisböck's syndrome: its hematologic, biochemical and hormonal parameters". Angiology. 29 (7): 520–533. doi:10.1177/000331977802900703. PMID 686487. S2CID 42326090.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mithoowani, Siraj; Laureano, Marissa; Crowther, Mark A.; Hillis, Christopher M. (10 August 2020). "Investigation and management of erythrocytosis". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 192 (32): E913 – E918. doi:10.1503/cmaj.191587. PMC 7829024. PMID 32778603.

- ^ Couck I, Lewi L (June 2016). "The Placenta in Twin-to-Twin Transfusion Syndrome and Twin Anemia Polycythemia Sequence". Twin Research and Human Genetics. 19 (3): 184–190. doi:10.1017/thg.2016.29. PMID 27098457. S2CID 7376104.

- ^ Ebert BL, Bunn HF (September 1999). "Regulation of the erythropoietin gene". Blood. 94 (6): 1864–1877. doi:10.1182/blood.V94.6.1864. PMID 10477715.

- ^ a b Perrotta S, Nobili B, Ferraro M, Migliaccio C, Borriello A, Cucciolla V, et al. (January 2006). "Von Hippel-Lindau-dependent polycythemia is endemic on the island of Ischia: identification of a novel cluster". Blood. 107 (2): 514–519. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-06-2422. PMID 16210343. S2CID 17065771.

- ^ a b Ang SO, Chen H, Hirota K, Gordeuk VR, Jelinek J, Guan Y, et al. (December 2002). "Disruption of oxygen homeostasis underlies congenital Chuvash polycythemia". Nature Genetics. 32 (4): 614–621. doi:10.1038/ng1019. PMID 12415268. S2CID 15582610.

- ^ a b Shahani S, Braga-Basaria M, Maggio M, Basaria S (September 2009). "Androgens and erythropoiesis: past and present". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 32 (8): 704–716. doi:10.1007/BF03345745. PMID 19494706. S2CID 30908506.

- ^ Kwaan HC, Wang J (October 2003). "Hyperviscosity in polycythemia vera and other red cell abnormalities". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 29 (5): 451–458. doi:10.1055/s-2003-44552. PMID 14631544.

- ^ Wallach JB (2007). Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests (7th ed.). Lippencott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-3055-6.

- ^ Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment. McGraw Hill Lange. 2008. p. 438.

- ^ Salazar Vázquez, B. Y., Cabrales, P., Tsai, A. G., Johnson, P. C., & Intaglietta, M. (2008). Lowering of blood pressure by increasing hematocrit with non nitric oxide scavenging red blood cells. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology, 38(2), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2007-0081OC

- ^ Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, Barbui T (January 2018). "Polycythemia vera treatment algorithm 2018". Blood Cancer Journal. 8 (1) 3. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0042-7. PMC 5802495. PMID 29321547.

- ^ "Polycythemia, Primary Familial snd Congenital; PFCP". OMIM.

- ^ Burkeman O (29 Sep 2013). "Malcolm Gladwell: 'If my books appear oversimplified, then you shouldn't read them'". Guardian newspaper.

- ^ Bailey DM, Davies B (September 1997). "Physiological implications of altitude training for endurance performance at sea level: a review". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 31 (3): 183–190. doi:10.1136/bjsm.31.3.183. PMC 1332514. PMID 9298550.

- ^ Wajcman H, Galactéros F (2005). "Hemoglobins with high oxygen affinity leading to erythrocytosis. New variants and new concepts". Hemoglobin. 29 (2): 91–106. doi:10.1081/HEM-58571. PMID 15921161. S2CID 10609812.

- ^ Kralovics R, Prchal JT (February 2000). "Congenital and inherited polycythemia". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 12 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1097/00008480-200002000-00006. PMID 10676771.

- ^ Sottas PE, Robinson N, Fischetto G, Dollé G, Alonso JM, Saugy M (May 2011). "Prevalence of blood doping in samples collected from elite track and field athletes". Clinical Chemistry. 57 (5): 762–769. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2010.156067. PMID 21427381.

- ^ a b c d Keohane C, McMullin MF, Harrison C (November 2013). "The diagnosis and management of erythrocytosis" (PDF). BMJ. 347 (nov18 1) f6667. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6667. PMID 24246666. S2CID 1490914.

- ^ Percy MJ, Zhao Q, Flores A, Harrison C, Lappin TR, Maxwell PH, et al. (January 2006). "A family with erythrocytosis establishes a role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (3): 654–659. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508423103. PMC 1334658. PMID 16407130.

- ^ Percy MJ, Furlow PW, Beer PA, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, Lee FS (September 2007). "A novel erythrocytosis-associated PHD2 mutation suggests the location of a HIF binding groove". Blood. 110 (6): 2193–2196. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-04-084434. PMC 1976349. PMID 17579185.

- ^ Percy MJ, Furlow PW, Lucas GS, Li X, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, Lee FS (January 2008). "A gain-of-function mutation in the HIF2A gene in familial erythrocytosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (2): 162–168. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa073123. PMC 2295209. PMID 18184961.

- ^ Gale DP, Harten SK, Reid CD, Tuddenham EG, Maxwell PH (August 2008). "Autosomal dominant erythrocytosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with an activating HIF2 alpha mutation". Blood. 112 (3): 919–921. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-04-153718. PMID 18650473. S2CID 14580718.

- ^ "Polycythemia Vera". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ Tremblay D, Alpert N, Taioli E, Mascarenhas J (August 2021). "Prevalence of unexplained erythrocytosis and thrombocytosis - an NHANES analysis". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 62 (8): 2030–2033. doi:10.1080/10428194.2021.1888377. PMID 33645402. S2CID 232078345.

- ^ Fulco, C. S.; Rock, P. B.; Cymerman, A. (2000). "Improving athletic performance: is altitude residence or altitude training helpful?". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 71 (2): 162–171. ISSN 0095-6562. PMID 10685591.